Abstract

We describe the synthesis and properties of five dinucleotide fluorescent cap analogues labelled at the ribose of the 7-methylguanosine moiety with either anthraniloyl (Ant) or N-methylanthraniloyl (Mant), which have been designed for the preparation of fluorescent mRNAs via transcription in vitro. Two of the analogues bear a methylene modification in the triphosphate bridge, providing resistance against either the Dcp2 or DcpS decapping enzymes. All these compounds were prepared by ZnCl2-mediated coupling of a nucleotide P-imidazolide with a fluorescently labelled mononucleotide. To evaluate the utility of these compounds for studying interactions with cap-binding proteins and cap-related cellular processes, both biological and spectroscopic features of those compounds were determined. The results indicate acceptable quantum yields of fluorescence, pH independence, environmental sensitivity, and photostability. The cap analogues are incorporated by RNA polymerase into mRNA transcripts that are efficiently translated in vitro. Transcripts containing fluorescent caps but unmodified in the triphosphate chain are hydrolysed by Dcp2 whereas those containing a α-β methylene modification are resistant. Model studies exploiting sensitivity of Mant to changes of local environment demonstrated utility of the synthesized compounds for studying cap-related proteins.

Introduction

A characteristic feature of almost all eukaryotic mRNAs is the presence of a cap at the 5′ terminus. The cap is an unique residue composed of a 7-methylguanosine moiety connected to the mRNA body via a triphosphate linkage, m7GpppGpNp(Np)n1, 2. The unusual chemical structure of the cap is pivotal for essentially all stages of mRNA metabolism: synthesis, splicing, nucleocytosolic transport, intracellular localization, translation, and turnover. The cap itself is a target for specific pyrophosphatases, such as the Dcp1/2 decapping complex and the decapping scavenger enzyme DcpS, which play a vital role in mRNA turnover. Consequently, synthetic analogues of the cap have proven to be valuable tools for investigating numerous biological processes as well as being applicable in biotechnology and medicine3.

One application is the enzymatic synthesis of capped RNAs with either bacteriophage4 or bacterial5 RNA polymerases. However, these polymerases do not discriminate between Guo and m7Guo for addition of the growing polynucleotide chain, and as a result, 30–50% of the RNAs are capped in the reverse orientation, i.e., Gpppm7GpNp(Np)n5. This is prevented by replacing conventional cap analogues with anti-reverse cap analogues (ARCAs) that contain modifications at either the 2′- or 3′-positions of the m7Guo moiety5, 6. mRNAs with modified caps have proven to be beneficial for both basic research and practical applications7–13.

There are two general types of chemical modifications that can be made in the cap analogue. One is to change its properties so as to alter its biological features e.g., increasing its affinity to a certain protein or resistance to an enzymatic action2, 7. The second is to introduce features that allow one to monitor the cap analogue or capped mRNA in a biological system, preferably without altering its biological features. Introducing a fluorophore into the cap analogue is a promising approach for achieving the latter. Fluorescence is a potent technique to obtain information about the behaviour of molecules within biological systems14, 15. For instance fluorescence microscopy is capable of imaging the cellular distribution of macromolecules with high sensitivity16–18, and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) allows one to study macromolecule dynamics and interactions19, 20. Recent developments in fluorescence microscopy have enabled single-molecule methods that can provide otherwise inaccessible information on statistical distribution and time trajectories21, 22. To date, fluorescent nucleotides have found a plethora of applications in biochemistry23–25, molecular biology26, 27 and nanotechnology28, 29.

Typically, a fluorophore is composed of two or more connected aromatic rings, which are essential to shift the excitation wavelength into the visible region. In some cases, probes are large enough to interfere with binding interactions between a protein and its ligand. However, there are also a number of compact, low molecular weight dyes that can serve this purpose. Groups such as anthraniloyl (Ant), N-methylanthraniloyl (Mant) and trinitrophenyl (TNP) are environmentally sensitive fluorophores that emit a stronger signal upon binding to a target30. Nucleotides labelled with these tags closely mimic naturally occurring nucleotides in their interactions with molecular targets31–33. Typically, these fluorophores are covalently attached to one or both OH groups of the ribose ring32. (M)Ant-labelled nucleotides were successfully used to study the behaviour of numerous proteins, including bacterial toxins34–37, G proteins38 and human adenosylcyclases39, 40. One complication upon derivatization of ribose OH groups is formation of a mixture of 2′ and 3′ regioisomers that exist in a dynamic equilibrium34, 41. Nonetheless, the small size of these fluorophores makes them promising candidates for mRNA cap labelling. The synthesis of fluorescent cap analogues has been previously reported31, 42, 43, but none have been designed to be incorporated into mRNA transcripts or modified in the phosphate chain to change their susceptibility to enzymatic degradation. The latter cap analogues have proven to be valuable for the study of cap-related processes8, 44–47. Combining these properties – fluorescence, the ability to be incorported into mRNA, and stability to enzymatic hydrolysis – should allow one to examine new aspects of cap-related processes both in vivo and in vitro.

We describe here a method for preparation and biochemical properties of five cap analogues, compounds 1-5, labelled with either Ant or Mant, that are potentially useful for the study of mRNA translation, turnover, or other cellular processes involving mRNA. Due to the replacement of one bridging oxygen by a methylene moiety, compounds 3 and 4 are stable to degradation by the Dcp1/2 complex47 and DcpS48, respectively. Because the 2′ OH group of compound 5 is methylated, the fluorescent tag is definitively localized to the 3′ position. Hence, this analogue might be used to examine interactions with eIF4E and other cap binding proteins without any potential problems caused by migration of the fluorophore.

Results and discussion

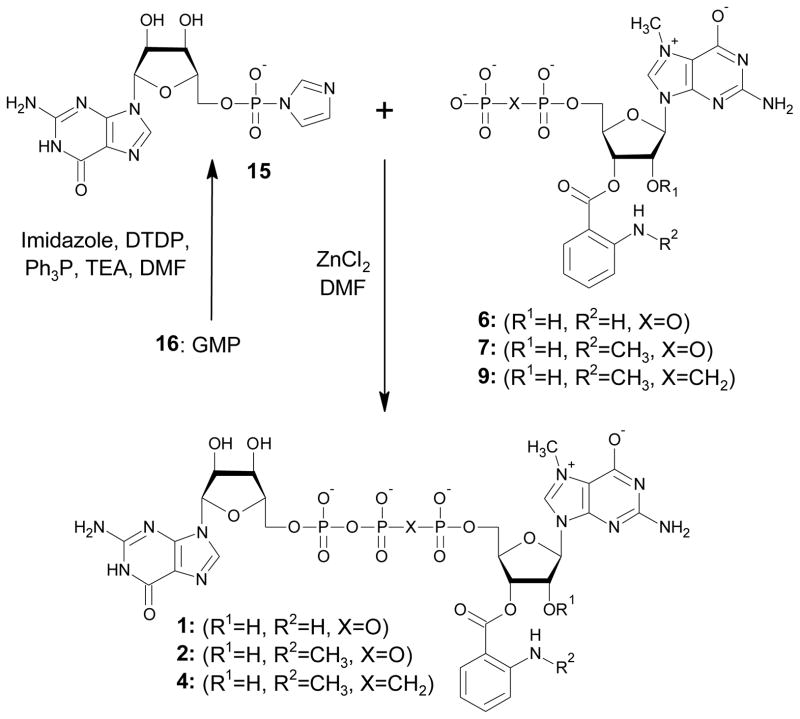

Chemical synthesis

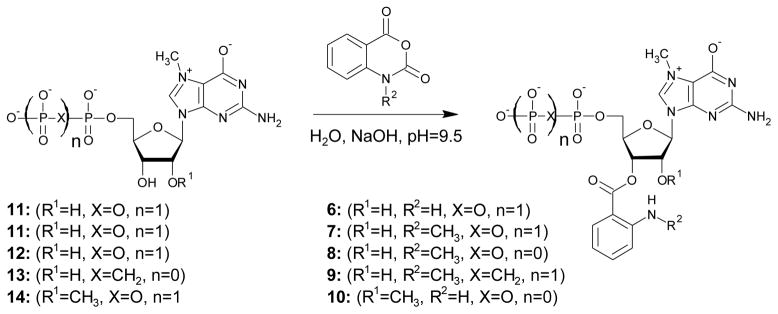

Five triphosphate dinucleotide cap analogues bearing either Ant or Mant fluorescent tags were prepared (Fig. 1). Two of these compounds (1-2) are derivatives of the canonical cap dinucleotide, m7GpppG, without any modification of the phosphate chain, whereas two others (3-4) have one of the bridging oxygen atoms substituted by a methylene group. Both high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry (MS) indicated that compounds 1-4 exist a mixture of two regioisomers in a dynamic equilibrium, which is consistent with previous publications on (M)Ant-labelled nucleotides49, 50. Compound 5 also bears a 2′-O methyl group on m7G, which blocks the isomerisation and results in a defined 3′position for the Ant moiety. During syntheses of the final dinucleotides 1-5, two reactions should be noted as key synthetic steps, the label attachment to nucleotide and the ZnCl2-mediated coupling of two nucleotide subunits to form a dinucleotide 5′,5′-triphosphate. The synthesis of intermediates 6-10 is depicted in Scheme 1. For label attachment we applied synthetic procedures similar to those previously described for anthraniloyl-m7GTP and N-methylanthraniloyl-diadenosinetetraphosphates43, 51, but with several modifications. 7-Methylguanine-containing nucleoside mono- or diphosphates were treated with either isatoic or N-methylisatoic anhydride in aqueous solution at pH 9.5 to obtain the mononucleotide labelled with Ant or Mant, respectively. Reversed phase (RP) HPLC was used to follow the reaction progress. When m7GDP (11) was treated with isatoic anhydride, both expected regioisomers of Ant-m7GDP (6) were detected. However, another product emerged during the reaction progress. This side product displayed a considerably higher retention time than the expected products. Further analysis by MS revealed that it was 2′, 3′-diAnt-m7GDP, i.e., possessing two Ant residues, presumably one each on the 2′ and 3′ OH groups. The analogous side product was observed during preparation of Mant-m7GDP (7), but the observed rate of diMant-m7GDP formation was ~2-fold slower than for diAnt-m7GTP. The highest ratio of mono- to disubstituted product was obtained when both reagents were nearly equimolar. Specifically, 1–1.2 eq. of anhydride were added in small portions (~0.2 eq.) 5–6 times over a period of 1h. Under these conditions, the undesired side-product was ~10%. We initially attempted purification of compounds 6-10 from unreacted and doubly labelled nucleotides by applying ion-exchange chromatography, but we observed partial decomposition of the products to unlabelled substrates and free (M)Ant acid during evaporation of TEAB buffer. Furthermore, the TEA salts of 6-10 deteriorated even if stored in the cold. To reduce this loss, nucleotides 6-10 were immediately used as reactants in the coupling reactions described below.

Fig. 1.

Structures of synthesised cap analogues

Scheme 1.

Labelling of m7G-containing nucleotides with isatoic or N-methylisatoic anhydride. For the sake of clarity only 3′ regioisomer of compounds 6-9 is depicted.

In order to obtain intermediates 6-10 in pure and stable form for structure confirmation by NMR, we switched to another purification protocol – size exclusion chromatography on G-15 resin43, 52. Even though this method resulted in pure sodium salts of compounds 6-10, size exclusion chromatography cannot be used in the overall synthesis scheme because the sodium salts are insoluble in the organic solvents used for the subsequent coupling reaction.

The key step in the preparation of compounds 1-5 was ZnCl2-mediated coupling of two nucleotides to form a dinucleoside 5′,5′-triphosphate. One nucleotide was converted to the active P-imidazolide and the second nucleotide acted as a nucleophilic agent (6-10), which allowed formation of the pyrophosphate bond53. The reactants, products, HPLC conversion, and preparative yield of each coupling reaction are summarized in Table 1. In principle, two alternative approaches are possible for triphosphate bridge formation. In the first, a nucleotide is activated at the stage of monophosphate and then coupled to flouorophore-labelled 7-methylguanosine diphosphate or 7-methylguanosine bisphosphonate (Scheme 2). In the second, guanosine diphosphate or guanosine bisphosphonate is activated and coupled with flourophore-labelled 7-methylguanosine monophosphate (Scheme 3). A third, theoretically possible approach is the activation of a nucleotide (mono- or diphosphate) labelled with Ant or Mant, but this was considered unlikely to succeed and was not tested. To illustrate the first route of synthesis, compounds 1 and 2 were prepared using activated GMP (GMP-Im, 15) and either Ant-m7GDP (6) or Mant-m7GDP (7), respectively. Conversion to products was high in both cases: 92% for Ant-m7GDP and 81% for Mant-m7GDP. A similar synthetic route, coupling of Mant-m7GpCH2p (9) with 15, was used to synthesize compound 4, which has a methylene bridge between the β and γ phosphates. (Scheme 2). The first reactant (9) was synthesised by the previously described methodology of preparing Mant-labelled nucleotides starting from m7GpCH2p (13) (Scheme 1) and reacted with 15. Compound 3, which has a methylene bridge between the β and γ phosphates was prepared by coupling Mant-m7GMP (8) with GpCH2p-Im (18) (Scheme 3). 18 was prepared starting from guanosine, which was converted to GpCH2p (20) in Yoshikawa-like phosphonylation using methylenebis(phosphonic) dichloride54, and then 20 was converted into the phosphoroimidazolidate 18. MS analysis demonstrated that 20 was slightly contaminated by methylenobisphosphonate, which co-eluted during ion-exchange chromatography. As a result, methylene-bis(1-imidazolyl)phosphonate was formed in the next step. This contaminant diminished the yield of coupling between 8 and 18 because of the formation of various side products such as Mant-m7GppCH2p or Mant-m7GppCH2ppm7G-Mant. Despite this impediment, compound 3 was obtained with yield of 12% after two purification steps, ion-exchange and RP HPLC purification (HPLC conversion 63%). Coupling of 8 and 18 afforded compound 3 with 8% yield after a two-step purification. Compound 5 was prepared by coupling of Ant-m27,2′-OGMP (10) with 17, which was obtained from GDP (19) (Scheme 3). m2′-OGMP was obtained from m2′-OGuo by Yoshikawa phosphorylation. The next steps were methylation at the N7 position followed by tagging with the Ant moiety. Importantly, blocking of the 2′-OH with a methyl group effectively prevented the formation of diAnt-substituted products. This enabled us to use 1.5 eq. of isatoic anhydride in a single addition, thus shortening the reaction time. Compound 5 was prepared with 26% yield after a two-step purification.

Table 1.

Reactants and products structures and yields of formation dinucleotide cap analogues.

| Product (No) | ελ260 (M−1cm−1) | Nucleophile (No) | Activated nucleotide (No) | HPLC conv. [%] | Yield a/b [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ant-m7GpppG (1) | 21700 | Ant-m7GDP (6) | GMP-Im (15) | 92 | 39/34 |

| Mant-m7GpppG (2) | 26800 | Mant-m7GDP (7) | GMP-Im (15) | 81 | 36/17 |

| Mant-m7GppCH2pG (3) | 26400 | Mant-m7GMP (8) | GpCH2p-Im (18) | 63 | 36/12 |

| Mant-m7GpCH2ppG (4) | 24000 | Mant-m7GpCH2p (9) | GMP-Im (15) | 72 | 23/8 |

| Ant-m27,2′-OGpppG (5) | 21600 | Ant-m27,2′-OGMP (10) | GDP-Im (17) | 95 | 83/26 |

yield after ion exchange chromatography;

yield after additional RP HPLC purification

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 1, 2, 4. DTDP – 2;2′-dithiodipyridine; Ph3P – triphenylphosphine; TEA – triethylamine; DMF - dimethylformamid

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 3, 5. DTDP – 2;2′-dithiodipyridine; Ph3P – triphenylphosphine; TEA – triethylamine; DMF - dimethylformamid

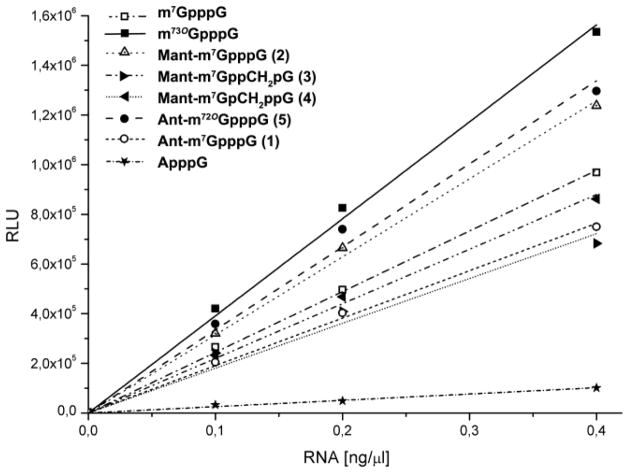

Spectroscopic studies

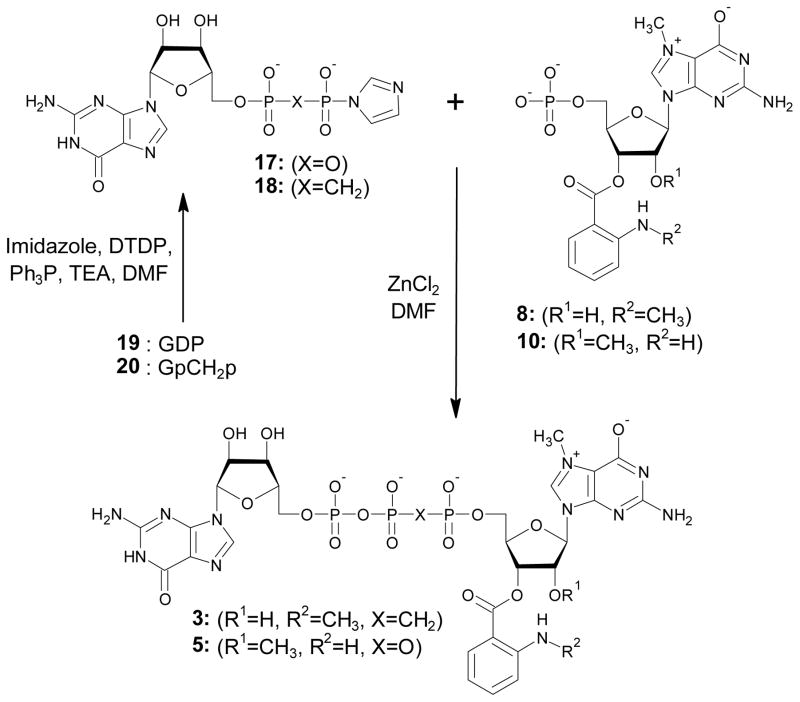

Compounds 1, 2, and 5 were selected for detailed spectroscopic studies. Fig. 2 shows electronic absorption and emission spectra recorded in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and Table 2 summarizes the spectroscopic data. It is known that the spectroscopic properties of aminobenzoic acid derivatives depend on the amino group substituent and modification of the carboxyl group55, 56. Therefore, methylanthranilate (AntOMe) and methyl-N-methylanthranilate (MantOMe) were selected as reference probes for spectroscopic studies. The absorption and emission spectra of AntOMe and MantOMe in buffer solutions at pH 5.18 and 8.96 are shown in Fig. S1. There was no difference between the absorption and emission peaks over a pH range of 5 to 9. Quantum yields and lifetimes were also identical within experimental error (Table S1). Similarly the absorption and emission peaks of (M)Ant moieties attached to the cap did not change significantly over this pH range (Fig. 2). The absorption spectra have two maxima, at 254 and 334 nm (361 nm for compound 2), which correspond to the absorption of the nucleobase and Ant (or Mant), respectively. Interestingly, the absorbance maximum for Ant in 1 is red-shifted 5 nm in comparison to AntOMe, and the same phenomenon occurs for the Mant-labelled compound (2). The broad shoulder in the absorption spectrum at 280 nm corresponds to the 7-methylguanosine moiety. That absorbance maximum exhibits pH dependence, due to the presence of the ionizable N1 proton in m7Guo. This dependence was used to calculate the pKa of the m7Guo N1 ionization in the cap analogues. The pKa values for compounds 1, 2, and 5 were 7.41, 7.42 and 7.49, respectively. These values are similar to the pKa of the unmodified cap analogue (7.50), which indicates that introduction of these fluorescent tags does not alter ionization of the N1 proton of m7Guo, an important finding since we sought to make minimal changes to the biological properties of the cap analogues. Interestingly, the incorporation of Ant or Mant moieties into the cap structure increased their fluorescence intensities and lifetimes. This suggests a close interaction between the fluorescent probe and hydrophobic parts of the nucleotide, since such interactions would be expected to change the polarity in the vicinity of the fluorophore. Emission spectra of cap analogues recorded in methanol or ethanol revealed a considerable increase in quantum yields, which is similar to the results obtained with the reference probes. The contribution of the short lifetime component was significantly decreased if the cap analogue was dissolved in methanol. This component vanished totally in ethanol and only the long lifetime could be detected. This is likely due to stabilisation of the excited state by the solvent, which diminishes the rate of non-radiative decay of the excited fluorophore and leads to an increase in fluorescence lifetime. A similar increase influorescence intensity could also possibly occur upon binding to cap-recognising proteins due to changes in local polarity. Similar observations on quantum yield augmentation and lifetime extension were reported by Turchiello et al.57.

Fig. 2.

Absorbance and emission spectra of Ant-m7GpppG (A), Mant-m7GpppG (B), and Ant-m27,2′O GpppG (C) in phosphate buffer at pH 5.18 and pH 8.96. Emission spectra of the indicated fluorescent mRNAs containing either Ant- or Mant-modified caps (D). The concentration of each cap analogue was 11.7 μM. The concentrations of RNA were 6.7 nM and 10.4 nM for Ant-or Mant-labelled transcripts, respectively. The concentration of ARCA-capped RNA was 10 nM.

Table 2.

Spectroscopic properties of cap analogues in phosphate buffer and organic solvents.

| Compound | Solution[a] | Absorption | λmax (nm) | Fluorescence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λmax (nm) | ελmax (M−1cm−1) | QY | lifetime | |||

| Ant-m7GpppG (1) | PBS pH = 5.18 |

334 | 4080 | 422.5 | 0.138 | τ1= 4.24 ns α1= 0.3181 τ2= 1.78 ns α2= 0.6819 τAV= 2.56 ns χR2=1.026 |

| PBS pH = 8.96 |

334 | 4040 | 422.5 | 0.135 | τ1= 4.15 ns α1= 0.3172 τ2= 1.79 ns α2= 0.6828 τAV= 2.54 ns χR2= 0.973 |

|

| MeOH | 341.5 | 4800 | 415 | 0.453 | τ1= 7.30 ns α1= 0.8493 τ2= 3.20 ns α2= 0.1507 τAV= 6.69 ns χR2= 0.983 |

|

| EtOH | 342.5 | 4670 | 413 | 0.594 | τ1= 8.08 ns χR2= 1.195 | |

| Ant-m7,2′-OGpppG (5) | PBS pH = 5.18 |

334 | 4110 | 424 | 0.161 | τ1= 4.23 ns α1= 0,3689 τ2= 2.04 ns α2= 0.6311 τAV= 2.85 ns χR2= 0.981 |

| PBS pH = 8.96 |

334 | 4100 | 424 | 0.156 | τ1= 4.23 ns α1= 0.3903 τ2= 2.10 ns α2= 0.6097 τAV= 2.93 ns χR2=0.954 |

|

| Mant-m7GpppG (2) | PBS pH = 5.18 |

361 | 4670 | 446 | 0.236 | τ1= 7.11 ns α1= 0.4050 τ2= 2.61 ns α2= 0.5950 τAV= 4.43 ns χR2= 1.101 |

| PBS pH = 8.96 |

361 | 4730 | 446 | 0.258 | τ1= 7.65 ns α1= 0.4498 τ2= 2.81 ns α2= 0.5502 τAV= 4.99 ns χR2= 1.084 |

|

| MeOH | 358.5 | 5880 | 430 | 0.439 | τ1= 8.05 ns α1= 0.6996 τ2= 5.54 ns α2= 0.3004 τAV= 7.30 ns χR2= 1.036 |

|

| EtOH | 358.5 | 5500 | 430 | 0.484 | τ1= 8.24 ns χR2= 1.219 | |

PBS = phosphate buffer 0.067 M

The photostability of compounds 1, 2, and 5 was assessed with time-based fluorescence measurements. The compounds were exposed to light for 9 h to induce photobleaching. We found less than a 3% loss of fluorescence intensity. Furthermore, there were no detectable changes in the shape of excitation spectra before and after exposure to light (data not shown).

NMR studies

The fact that compounds 1-4 exist as equilibrium mixtures of 2′ and 3′ (M)Ant regioisomers is reflected in their 1H NMR spectra49, 50. Some protons display different chemical shifts depending on whether they are assigned to the 2′ or 3′ regioisomer, which allows one to calculate the ratio between isomers using the 1H NMR spectrum of the configurationally stable compound 5 as a reference. In the case of Ant-m7GpppG, the 2′ and 3′ isomer made up 32% and 68%, respectively. The distribution of isomers was similar for Mant-m7GpppG (42% and 58%) (Table S2). These findings are in general agreement with previous studies of (M)Ant-labelled mononucleotides. Thus, the stacking interactions between m7G and G rings in dinucleotide cap analogues have a minimal impact on the distribution between 2′ and 3′ isomers. Interestingly, the ratios of these regioisomers for compounds 1 and 2 are similar to the ratios of fluorescence lifetimes, suggesting that the short and long lifetime are derived from the 3′ and 2′ regioisomers, respectively. However, it should be noted that compound 5, which has a fixed position for the Ant moiety, also shows two different fluorescence lifetimes (Table 2). Hence, the assumption that observed lifetimes correlate with different conformations of the ribose ring is a more likely explanation for this phenomenon. The conformation of the ribose ring of cap analogue 5 was analyzed in terms of a dynamic equilibrium between two favored puckered conformations N and S58, 59. The percentages of the two conformers were calculated using experimentally determined vicinal coupling constants 3JH,H for protons in the sugar moiety, which has been reported previously61. Using the assigned coupling constants, the fractions of N and S conformers were determined to be 0.37 and 0.63, respectively. These values correlate well with the contributions of fluorescence lifetimes originating from different excited states (see Table 2). However, in the case of compounds 1 and 2, the populations of S and N conformers do not correlate with the calculated fluorescence lifetimes contributions (Table S3). This implies that in the case of compounds with 2′/3′-shifting of (M)Ant groups, the observed lifetime contributions may stem from a combination of different conformations of sugar moiety and the regioisomerism. We are currently investigating this phenomenon further with molecular modeling methods.

In vitro synthesis of capped RNAs

We examined the efficiencies for incorporation of compounds 1-5 into short (48 nt) RNA transcripts by T7 RNA polymerase. Transcripts synthesised in the presence of compounds 1-5 were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and capping efficiency was measured after exposure of the gel to autoradiography. The capping efficiencies for compounds 1-5 are presented in Table 3. The capping efficiency for the parent compound m7,3′-OGpppG was 72±2%. It appears that both Ant and Mant moieties are well tolerated by T7 polymerase since the capping efficiency for cap analogues 1-5 was only slightly lower. A similar observation has been reported for biotin-labelled cap analogues 60.

Table 3.

In vitro biochemical properties of cap analogues 1–5

| No | Cap analogue | Capping efficiency [%] | In vitro decapping [%] | Translational efficiencya | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 30 min | ||||

| 1 | Ant-m7GpppG | 50±3 | 26±8 | 44±16 | 0.82±0.27 |

| 2 | Mant-m7GpppG | 57±2 | 37±11 | 52±12 | 1.34±0.05 |

| 3 | Mant-m7GppCH2pG | 63±5 | 5±9 | 11±10 | 0.69±0.11 |

| 4 | Mant-m7GpCH2ppG | 70±2 | 34±4 | 54±5 | 0.85±0.12 |

| 5 | Ant-m27,2′-OGpppG | 68±6 | 29±9 | 48±9 | 1.26±0.28 |

| - | m27,3′-OGpppG | 76±2 | 61±12 | 76±10 | 1.41±0.26 |

| - | m7GpppG | ndb | nd | nd | 1±0 |

| - | ApppG | nd | nd | nd | 0.12±0.01 |

normalised to m7GpppG;

not determined

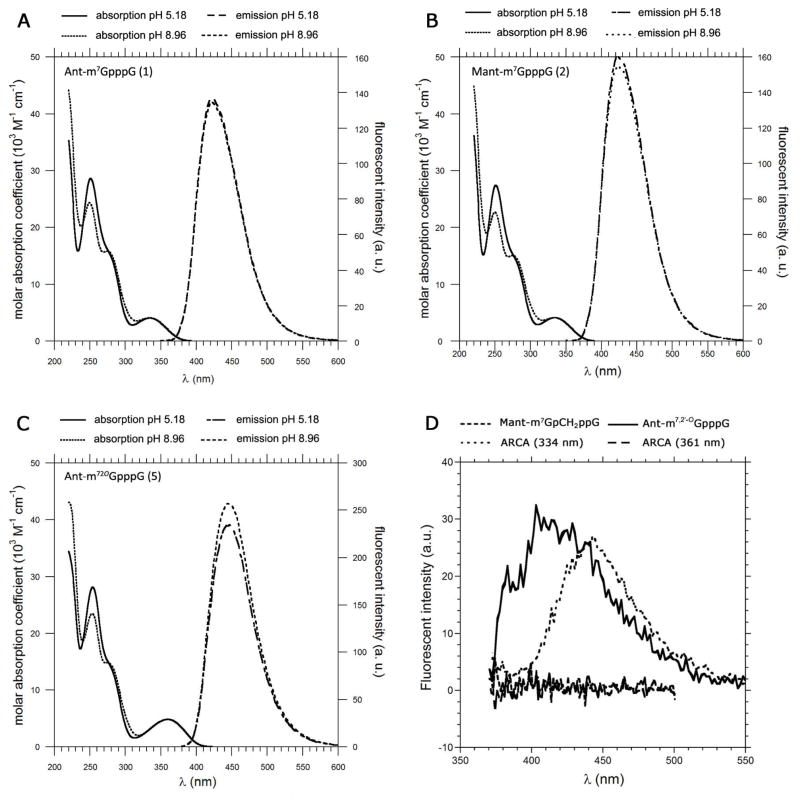

Translation in vitro

The translational properties of mRNAs containing compounds 1-5 were assessed using a rabbit reticulate lysate (RRL) translation system programmed with firefly luciferase mRNA Fig. 3 and Table 3). Due to a significant percentage of reverse-incorporated cap analogue, i.e., Gpppm7GpNp(Np)n, the translational efficiency of mRNA capped with m7GpppG was considerably lower than that of mRNAs capped with ARCAs. Since compounds 1-5 are functional equivalents of ARCAs, the results indicated that the presence of the (M)Ant tag slightly impedes recognition of the cap by the translational machinery. The translational efficiencies of mRNAs containing compounds 3 and 4, which possess the methylene modification, were lower than those of their unmodified counterparts 1, 2, and 5 (Fig. 3 and Table 3), which agrees with previous findings.

Fig. 3.

Luciferase activity as a function of concentration of mRNA capped with various ARCAs.

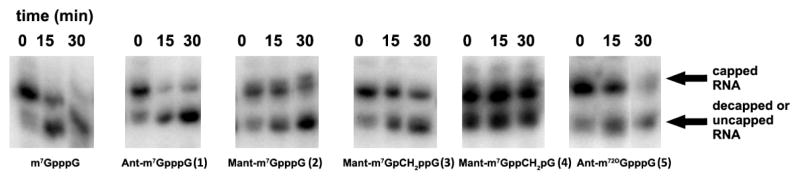

Decapping assays

Short capped transcripts (48 nt) were subjected to incubation with the Dcp1/2 decapping complex from Schizosaccharomyces pombe (SpDcp1/2) in order to investigate their susceptibility to hydrolysis. This enzyme complex cleaves the pyrophosphate bond between the α and β phosphates yielding m7GDP and the decapped RNA. The capped and decapped (or uncapped) RNAs migrate differently on electrophoresis. The mobility of the ~30% of molecules that are uncapped is similar to that of decapped mRNA12.

Transcripts synthesised in the presence of compounds 1-5 were incubated for 0, 15, or 30 min with recombinant SpDcp1/2 and subjected to electrophoresis. The amount of RNA was then measured by autoradiography (Fig. 4). The upper band contains capped RNA and the lower band contains uncapped and decapped RNA. The percentage of capped RNA is calculated from ratio of the radioactivity of the upper band to the total radioactivity contained in the upper and lower bands. Decapping is expressed as the decrease in this percentage (Table 3). The presence of uncapped RNA is taken into account in the calculation of the extent of decapping by subtracting a no-enzyme control. RNAs capped with compounds 1, 2, 4 were cleaved by SpDcp1/2, but the rate of decapping was slightly slower for fluorescent mRNAs compared to mRNAs capped with reference analogues (m7GpppG and m27,3′-OGpppG)49. The transcript capped with cap analogue compound 3, bearing the α-β methylene modification, was not susceptible to SpDcp1/2, which is in agreement with previous studies45, 47.

Fig. 4.

In vitro hydrolysis of capped oligonucleotides by SpDcp1/2. All transcripts were synthesized from an Nco1-cut pluc-A60 template with T7 polymerase in the presence of [α-32P]GTP and various cap dinucleotides. After treatment with SpDcp1/2 for the indicated times, samples were loaded on a 10% RNA sequencing gel as described in Materials and Methods.

Sensitivity of fluorescence of the Mant labeled cap to changes of local environment

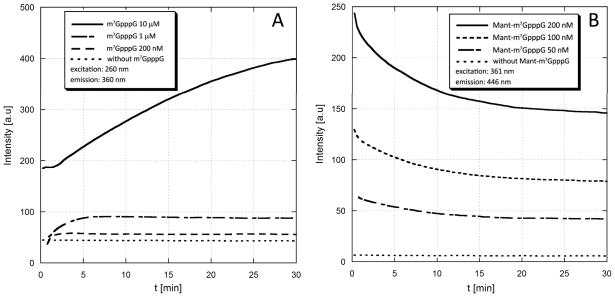

We tested wether the sensitivity of Mant label to changes in local polarity may be used for studying cap enzymatic degradation or protein binding. In the first model experiment, compound 2 was used as a substrate for hDcpS enzyme. DcpS hydrolyzes the residual m7GpppNn cap structures remaining after the cytoplasmic 3′→5′ degradation of mRNA by the exosome, cleaving between the γ and β phosphates and releasing m7GMP from capped (oligo)nucleotides61. DcpS is also involed with pre-mRNA splicing and has recently been identified as a therapeutic target for spinal muscular atrophy62. We found that upon the action of hDcpS Mant-m7GpppG is converted to Mant-m7GMP and GDP. The fluorescence intensity of Mant-m7GMP is lower than the intensity of the dinucleotide substrate (2), probably due to loss of interactions between the label and hydrophobic parts of the second nucleoside (guanosine). After complete cleavage of 2 by DcpS the fluorescence of the sample was diminished to ~60% of the initial intensity. This enabled monitoring the DcpS-catalyzed reaction progress by spectrofluorymetry (Fig. 5). Three reactions were performed at 200, 100 or 50 nM substrate concentration (Fig 5). Notably, even at the lowest concentration the fluorescence changes were sufficient to monitor reaction progress. For comparison, the non-labeled cap analogue, m7GpppG, also displays a weak fluorescence arising from m7G moiety. The fluorescence of m7GpppG is increased after cleavage by DcpS to m7GMP and GDP, due to loss of stacking interactions between the two nucleotides, and this can also be exploited for reaction progress monitoring (Fig. 5A). However, in the case of m7GpppG reaction can be followed at concentrations not lower than 1 μM. Hence, due to introduction of Mant moiety the sensitivity of the assay could be increased by ~20 fold. It is known that the presence of substituents at the 2′ or 3′ positions of m7G ribose moiety decreases the affinity of cap analogues for DcpS63. In agreement with that, the presence of Mant label attached to ribose of m7G residue decreased the reaction rate compared to unmodified cap cap analogue. However, due to small size of the Mant label, the compound could still serve as a relatively good substrate for DcpS. In our opinion, this results suggest that the Mant labeled cap analog 2 may be used as fluorescent molecular probe for assaying potential DcpS inhibitors. The conventional, HPLC-based assays are much more time-consuming, require high amounts of materials due to higher detection limits and are limited by problems with overlapping signals from the substarte or products and the inhibitor.

Fig. 5.

Monitoring the DcpS-catalyzed enzymatic hydrolysis of unlabeled (m7GpppG) and Mant-labeled (Mant-m7GpppG) cap analogues by spectrofluorymetry. (A). Unlabeled m7GpppG is cleaved by DcpS to m7GMP and GDP. The fluorescence intensity of the sample observed at the wavelength characteristic for m7G moiety (ex.=260 nm, em.=360 nm) increases along with reaction progress because in the dinucleotide (m7GpppG) fluorescence of m7G is partially quenched by intramolecular stacking between m7G and G. The fluorescence changes were sufficient to monitor reaction progress at concentration of 1 μM or higher(B) Mant-m7GpppG (2) is cleaved by DcpS to Mant-m7GMP and GDP. The fluorescence intensity of the sample observed at the wavelength characteristic for Mant moiety (ex.=361 nm, em.=446 nm) decreases along with reaction progress because the fluorescence of Mant in dinucleotide is enhanced by intramolecular interactions with hydrophobic parts of the second nucleoside (guanosine). The fluorescence changes were sufficient to monitor reaction progress at concentration of 50 nM or higher, i.e. 20-fold lower than for unlabeled m7GpppG. The DcpS concentration was 20 nM (experiment with m7Gp3G) or 200 nM (experiment with Mant-m7GpppG).

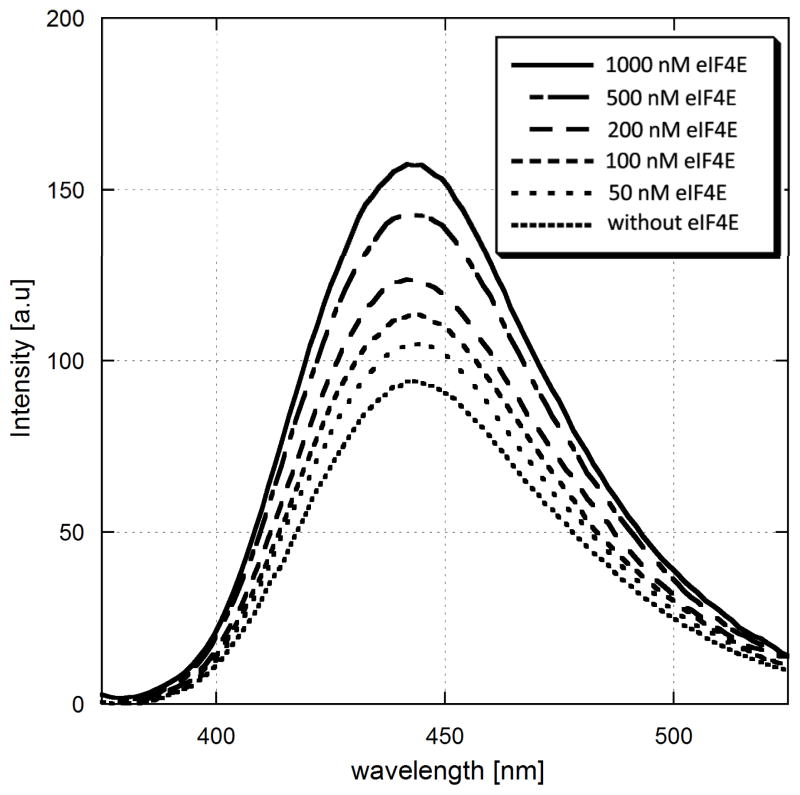

Another possible application of cap analogues 1-5 is to study protein-ligand interactions. As it was mentioned before, a number of studies indicated that fluorescence intensity of (M)Ant-labelled compounds is enhanced upon binding to a target protein. In a model experiment we used eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), an important component of translation initiation complex, which directly binds the mRNA cap structure. The interaction of cap with eIF4E constitutes an important cellular mechanism of regulation of gene expression at the translational level64. Morover, it has been established that eIF4E is overexpressed in many cancer cells and it has been demonstrated in several studies that preventing interaction of eIF4E with other constituents of the translation initiation complex may inhibit tumor growth65. We performed a “reverse titration” experiment, in which to a given concentration of compound 2 increasing amounts of eIF4E protein were added.

We observed that the Mant fluorescence intenstity was increased to up to 2-fold along with the increasing amount of eIF4E (Fig. 6). In contrast, if MantOMe was titrated by eIF4E no fluorescence augmentation could be noted (Fig. S3). The fluorescence enhancement can be attributed to the increase of local hydrophobicity upon cap binding to eIF4E. Hence, the results suggest that the prepared cap analogues can be applied to study protein-cap interactions. Interestingly, we also found that changes in compound 2 fluorescence properties may also be monitored upon excitation of Trp residues in eIF4E (Fig S4), which also may be used to study this protein.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity of Mant –labeled cap analog 2 to changes in local polarity caused by protein binding. Increase in Mant-m7GpppG fluorescence intensity observed upon addition of increasing amounts of eIF4E protein. The concentration of Mant-m7GpppG was 200 nM and the eIF4E concentrations were in range 50–1000 nM.

Conclusions

The fluorescently labeled analogues described here constitute a novel class of molecular probes that are potentially useful for a variety of biochemical and biophysical techniques. The cap itself demonstrates weak innate fluorescence, but due to its low quantum yield, hence it cannot be used for most fluorescence-based techniques.

An advantage of these compounds is their relatively straightforward and inexpensive preparation compared to some other molecular probes. Several biophysical features should make them particularly favorable for fluorescence-based biochemical assays: i) high quantum yields, ii) an excitation wavelength that is outside the absorbance range of proteins, and iii) striking photostability. Several biochemical features should make them favourable for in vitro studies of processes involving mRNA: i) ability to be incorporated into mRNA by RNA polymerases, ii) ability of fluorescent mRNAs to be recognized by the translational machinery, and iii) enzymatic susceptibility to decapping enzymes. Furtheremore, it was confirmed that the fluorescence of (M)Ant-labelled cap analogues is influenced by the polarity of the microenvironment and hence a useful read-out for protein-cap interactions. Introduction of the stabilizing α-β methylene modification to the polyphosphate bridge creates various opportunities to study decapping in vitro by means of fluorescence based assays. For instance, rate of the loss of fluorescence anisotropy after decapping initiation would be a measure of decapping rate, and the non-cleavable methylene-modified mRNA would serve as a control for specificity of the signal. Studies of this type could be conducted for either Dcp2 (using compound 3) or DcpS (using compound 4).

Experimental

General information

All intermediates were separated by ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-Sephadex A-25 (HCO3− form) column using a linear gradient of triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer in deionised water and after evaporation under reduced pressure with addition of ethanol, isolated as triethylammonium (TEA) salts. Final products were purified by means of semi-preparative RP HPLC and after a three-times repeated freeze-drying procedure they were isolated as ammonium salts. Yields were calculated either based on sample weight or optical units of the product. In this study an optical unit is defined as the absorption of compound solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH = 6, or 7 if a compound does not contain 7-methylguanosine residue) at 260 nm multiplied by volume of the solution in cm3. Analytical HPLC measurements were performed on an Agilent Tech. Series 1200 using a Supelcosil LC-18-T RP column (4.6 × 250 mm, flow rate 1.3 mL/min) with a 0–50% linear gradient of methanol in 0.05M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.9) for 15 min, UV-detection at 260 nm and fluorescence detection (excitation at 280 nm and detection at 337 nm). Semi-preparative HPLC preparations were performed on an Agilent Tech. Series 1200 apparatus using Discovery RP Amide C-16 HPLC column (25 cm × 21.2 mm, 5 μm, flow rate 5.0 mL/min) with a 0–30% linear gradient of acetonitrile in 0.05 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.9) for 120 or 180 min, and UV-detection at 260 nm. The structure and homogeneity of each final product were confirmed by chromatography on RP HPLC, mass spectrometry using negative electrospray ionization (MS ESI-) and NMR spectroscopy. 1H NMR and 31P NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a Varian UNITY-plus spectrometer at 399.94 MHz and 161.90 MHz respectively. 1H NMR chemical shifts were reported to sodium 3-trimethylsilyl-[2,2,3,3-D4]-propionate (TSP) in D2O as an internal reference and 31P NMR chemical shifts were reported to 20% phosphorus acid in D2O as an external reference. Mass spectra were recorded on a MicromassQToF 1 MS spectrometer.

General procedure for fluorescent tagging using isotoic or N-methylisotoic anhydrides

Synthesis of Mant or Ant-tagged nucleotides was achieved by following the synthesis procedure for Ant-GTP as reported by Hiratsuka 53 with modifications. A one equivalent of an appropriate nucleotide (TEA or sodium salt) was dissolved in MQ water and the pH was adjusted to 9.5 with 1M NaOH. To the solution, 0.2 eq of appropriate anhydride was added with continuous stirring. The pH of the solution was maintained at 9.6 by titration with NaOH and the anhydride was constantly added in small quantities (ca 0.2 eq) until the whole amount of the substrate was converted to products. Completion of the reaction was achieved within 6–8 hours, next the pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.0 with 50% acetic acid and the reaction mixture was filtered through a syringe filter to obtain a clear solution.

Purification of fluorescent-tagged nucleotides by size-exclusion chromatography and conversion to sodium salts

The products were separated via size-exclusion chromatography on a G15 Sephadex column (GE Healtcare) using MQ water as a eluent and after evaporation under reduced pressure isolated as triethylammonium (TEA) salts. TEA salts were converted to sodium salt by precipitation with a solution of anhydrous NaClO4 (2.5 eq. per negative charge) in dry acetone (~20 cm3/1 cm3 of MQ water). Afterwards the mixture was cooled at 4 °C, the precipitate was filtered, washed repeatedly with cold, dry acetone and dried in vacuo over P4O10.

Preparation of 2′-O-methylguanosine

2′-O-Methylguanosine was prepared as described previously by methylation of a 6-O-ethyl derivative of guanosine with diazomethane, which results in the formation of two regioisomers: 2′-O-methyl-6-O-ethylguanosine and 3′-methyl-6-O-ethylguanosine. Both compounds were separated by column chromatography using Dowex 1×2 Ion-Exchange Resin (200–400 mesh) using 0.3 M TEAB buffer as an eluent in an isocratic system.

General procedure for preparation of nucleotide imidazolide derivatives

All imidazolides were prepared according to previously described procedure66. An appropriate nucleotide (1 eq., TEA salt), imidazole (10 eq.) and 2,2′-dithiodipyridine (3 eq.) were dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) (the final concentration of nucleotide was ca 0.1 M). Triethylamine (2 eq.) and triphenylphosphine (3 eq.) were added subsequently and the mixture was stirred for 8–10 h. The product was precipitated from the reaction mixture with a solution of anhydrous NaClO4 (2.5 eq. one negative charge) in dry acetone (~10 cm3/1 cm3 of DMF). Afterwards the mixture was cooled at 4 °C, the precipitate was filtered, washed repeatedly with cold, dry acetone and dried in vacuo over P4O10.

Coupling of imidazolidates with nucleotides

In each case coupling leads to elongation of polyphosphate chain by one phosphate unit. This process was accomplished by dissolving the corresponding imidazolide (~1.25 eq) with an appropriate TEA salt (1 eq) and anhydrous ZnCl2 (8 eq.) in anhydrous DMF. After 1–2 hours the reaction was quenched via addition of solution of EDTA (1.25 mol per 1 mol of ZnCl2) in a water solution of NaHCO3. In the next step, the pH was adjusted to 7 and the product was purified via ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex.

Selective methylation at N7 position

7-methylguanosine was prepared by treatment of guanosine with (CH3O)2SO2 in DMA according to previously reported procedure. All nucleoside mono- and diphosphates containing 7-methylguanosine residue were synthesised employing CH3I in DMSO as was described earlier.

Phosphorylation and phosphonylation

2′-O-methylguanosine monophosphate was prepared by employing Yoshikawa reaction with distilled phosphorus oxychloride in trimethyl phosphate as a solvent, which has been described in previous studies66. Phosphonylation of guanosine with methylenebis-(phosphonic dichloride), resulting in GpCH2p, was achieved via modified Yoshikawa procedure as described in the literature7.

3′ (2′)-O-N-methylanthraniloyl guanosin-5′-yl monophosphate; 3′ (2′) Mant-GMP

GMP (TEA salt, 100 mg, 0.25 mmol) was dissolved in 5.5 cm3 of MQ water and the synthesis was performed as described in the general procedure. 13.2 mg (TEA salt; 10% yield) of white solid was obtained.

3′ (2′)-O-N-methylanthraniloyl 7-methylguanosin-5′-yl monophosphate; 3′ (2′) Mant-m7GMP; (9)

Method 1

m7GMP (TEA salt, 160 mg, 0.333 mmol) was dissolved in 5.5 cm3 of MQ water and the synthesis was performed as described in the general procedure. The product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.2 M). 1520 optical units (TEA salt; yield 31%) of pale yellow solid were obtained.

Method 2

Purification by size-exclusion chromatography and conversion to sodium salt. Starting from 77 mg of m7GMP and applying the same procedure as for Method 1 1.4 mg (sodium salt; yield 2%) of pale yellow solid was obtained.

isomer C2′ 1H NMR (ppm): 8.04 (1H, m, H6), 7.55 (1H, m, H4), 6.87 (1H, m, H3), 6.77 (1H, m, Hz, H5), 6.36 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=4.2 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.79 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=4.2 Hz, JH2′-H3′=5.0 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.8 (1H, overlapped with HDO, H3′m7G), 4.53 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.16–4.04 (2H, m, H5′m7G, H5″m7G), 4.14 (3H, s, N-CH3m7G), 2.87 (3H, s, N-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): 3.87 (1P, s). ESI MS: calcd: 509.11911 Found: 509.12169.

isomer C3′ 1H NMR (ppm): 8.10 (1H, m, H6), 8.04, 7.55 (1H, m, H4), 6.90 (1H, m, H3), 6.77 (1H, m, Hz, H5), 6.26 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.6 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.65 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=4.8 Hz, JH3′-H4′=3.0 Hz, H3′m7G), 5.02 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=5.7 Hz, JH2′-H3′=4.8 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.71 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.23–4.19 (1H, m, H5′m7G), 4.14 (3H, s, N-CH3m7G), 4.10–4.05 (1H, m, H5″m7G), 2.91 (3H, s, N-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): 3.87 (1P, s). ESI MS: calcd: 509.11911 Found: 509.12169.

31P NMR (ppm): 3.87 (1P, s). ESI MS: calcd: 509.11911 Found: 509.12169.

3′ (2′)-O-N-methylanthraniloyl 7-methylguanosin-5′-yl diphosphate; 3′ (2′) Mant-m7GDP; (7)

Method 1

m7GDP (TEA salt, 100 mg, 0.137 mmol; purity 90%) was dissolved in 2.5 cm3 of MQ water and the synthesis was performed as described in the general procedure. The product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.2 M). 1900 optical units (TEA salt; yield 92%) of pale yellow solid were obtained.

Method 2

Purification by size-exclusion chromatography and conversion to sodium salt. Starting from 101 mg of m7GDP and applying the same procedure as for Method 1. The product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.2 M). 18.8 mg (sodium salt; yield 18%) of pale yellow solid was obtained.

isomer C2′ 1H NMR (ppm): 8.04 (1H, m, H6), 7.54 (1H, m, H4); 6.87 (1H, m, H3), 6.74(1H, m, H5), 6.32 (1H, s, JH1′-H2′=3.0 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.78 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=3.0 Hz, JH2′-H3′=5.0 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.87 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=5.3 Hz, JH3′-H4′=5.0 Hz, H3′m7G), 4.51 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.45–4.27 (2H, m, H5″m7G, H5′m7G), 4.12 (3H, s, N-CH3m7G), 2.86 (3H, s, N-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): −6.05 (1P, s, Pβ); −10.52 (1P, s,). ESI MS: calcd: 589.085466 Found: 589.08546.

isomer C3′ 1H NMR (ppm): 8.09 (1H, m, H6), 7.54 (1H, m, H4), 6.87 (1H, m, H3), 6.74 (1H, m, H5), 6.24 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.9 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.66 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=5.4 Hz, JH3′-H4′=3.4 Hz, H3′m7G), 5.07 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=5.9 Hz, JH2′-H3′=5.4 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.73 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.45–4.27 (2H, m, H5″m7G, H5′m7G), 4.14 (3H, s, N-CH3m7G), 2.89 (3H, s, N-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): −6.05 (1P, s, Pβ); −10.52 (1P, s,). ESI MS: calcd: 589.085466 Found: 589.08546.

3′ (2′)-O-N-methylanthraniloyl 7-methylguanosin-5′-yl 1,2 methylene-diphosphate; 3′ (2′) Mant-m7GpCH2p; (8)

Method 1

m7GpCH2p (TEA salt, 120 mg, 0.176 mmol) was dissolved in 3.0 cm3 of MQ water and the synthesis was performed as described in the general procedure. 1400 optical units (TEA salt; yield 53%) of pale yellow solid were obtained.

Method 2

Purification by size-exclusion chromatography and conversion to sodium salt. Starting from 64 mg of m7GpCH2p TEA salt and applying the same procedure as for Method 1 6.6 mg (sodium salt; yield 10%) of pale yellow solid was obtained.

isomer C2′ 1H NMR (ppm): 8.04 (1H, m, H6), 7.54 (1H, m, H4); 6.87(1H, m, H3), 6.74 (1H, m, H5), 6.32 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=3.0 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.67 (1H, m, H2′m7G), 4.84 (1H, m, H3′m7G), 4.57 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.36 (2H, m, H5′m7G, H5″m7G), 4.13 (3H, s, N-CH3m7G), 2.86 (3H, s, N-CH3), 2.22 (2H, d, P-CH2-P) 31P NMR (ppm): 22.44 (1P, s, Pα), 11.84 (1P, s, Pβ). ESI MS: calcd: 587.10620 Found: 587.10641.

isomer C3′ 1H NMR (ppm): 8.10 (1H, m, H6), 7.54 (1H, m, H4); 6.87(1H, m, H3), 6.74 (1H, m, H5), 6.24 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=6.0 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.51 (1H, m, H3′m7G), 5.10 (1H, m, H2′m7G(), 4.73 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.36 (2H, m, H5′m7G, H5″m7G), 4.15 (3H, s, N-CH3m7G), 2.89 (3H, s, N-CH3), 2.22 (2H, d, P-CH2-P). 31P NMR (ppm): 22.44 (1P, s, Pα), 11.84 (1P, s, Pβ). ESI MS: calcd: 587.10620 Found: 587.10641.

3′ (2′)-O-anthraniloyl 7-methylguanosin-5′-yl diphosphate; 3′ (2′) Ant-m7GDP; (6)

Method 1

m7GDP (TEA salt, 250 mg, 0.378 mmol; purity 90%) was dissolved in 6.5 cm3 of MQ water and the synthesis was performed as described in the general procedure. The product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.2 M). 1304 optical units (TEA salt; yield 26%) of pale yellow solid were obtained.

Method 2

Purification by size-exclusion chromatography and conversion to sodium salt. Starting from 101 mg of m7GDP and applying the same procedure as for Method 1 12.4 mg (sodium salt; yield 11%) of pale yellow solid was obtained.

isomer C2′ 1H NMR (ppm): 8.01 (1H, m, H6), 7.42 (1H, m, H4), 6.86 (1H, m, H3), 6.82 (1H, m, H5), 6.36 (1H, m, JH1′-H2′=1.8 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.84 (1H, m, H2′m7G), 4.90 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=6.2 Hz, JH3′-H4′=5.5 Hz, H3′m7G), 4.42 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.47–4.26 (2H, m, H5″m7G, H5′m7G), 4.14 (3H, s, N-CH3m7G). 31P NMR (ppm): −6.31 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα=23.0 Hz, Pβ), −10.76 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα=23.0 Hz, Pα). ESI MS: calcd: 575.06982 Found:575.07000.

isomer C3′ 1H NMR (ppm): 8.04 (1H, m, H6), 7.42 (1H, m, H4), 6.86 (1H, m, H3), 6.82 (1H, m, H5), 6.25 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.6 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.67 (1H, m, H3′m7G), 5.09 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=5.6 Hz, JH2′-H3′=5.2 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.52 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.47–4.26 (2H, m, H5″m7G, H5′m7G), 4.16 (3H, s, N-CH3m7G). 31P NMR (ppm): −6.31 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα=23.0 Hz, Pβ), −10.76 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα=23.0 Hz, Pα). ESI MS: calcd: 575.06982 Found:575.07000.

2′-O-methyl, 3′-O-anthraniloyl 7-methylguanosin-5′-yl monophosphate; Ant-m27,2′-OGMP; (10)

Method 1

m7,2′-OGMP (TEA salt, 100 mg, 0.2 mmol) was dissolved in 4 cm3 of MQ water and synthesis was performed as described in the general procedure. The product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–0.9 M). 630 optical units (TEA salt; yield 21%) of pale yellow solid were obtained.

Method 2

Purification by size-exclusion chromatography and conversion to sodium salt. Starting from 77 mg of m7,2′-OGMP and applying the same procedure as for Method 1. 26.7 mg (sodium salt; yield 11%) of pale yellow solid was obtained.

1H NMR (ppm): 7.86 (1H, m, H6), 7.37 (1H, m, H4), 6.81(1H, m, H3), 6.68 (1H, m, H5), 6.27 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.5 Hz, H1′), 5.74 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=4.9 Hz, JH3′-H4′=2.7 Hz, H3′), 4.75 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=5.5 Hz, JH2′-H3′=4.9 Hz, H2′), 4.71 (1H, m, H4′), 4.20–4.08 (2H, m, H5′, H5″), 4.08 (3H, s, N-CH3), 3.51 (3H, s, O-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): 3.56 (1P, s). ESI MS: calcd: 509.11911 Found: 509.12169.

guanosin-5′-yl diphosphate; GDP; (19)

TEA phosphate (440 mg; 2.3 mmol) and anhydrous zinc chloride (750 mg 5.75 mmol) were stirred in 2 cm3 of anhydrous DMF until both substrates dissolved. Subsequently GMP-Im (Na salt, 490 mg, 1.15 mmol; purity 85%) and anhydrous zinc chloride (750 mg 5.75 mmol) were dissolved in 2cm3 of DMF. Both solutions were mixed and TEA (0.125 cm3; 1.71 mmol) was added to the mixture. The reaction was performed for 20 h and quenched by addition of EDTA (825 mg; 2.21 mmol) dissolved in 50 cm3 of 0.5 M NaHCO3 solution. The product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.0 M). 7480 optical units (TEA salt; yield 65%) were obtained.

7-methylguanosin-5′-yl diphosphate; m7GDP; (11)

GDP (TEA salt, 395 mg; 0.62 mmol) was dissolved in 6 cm3 of anhydrous DMSO and CH3I (0.6 cm3; 9.3 mmol) was added. The reaction was performed 2 for hours and quenched by addition of 75 cm3 of MQ water. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 using solid NaHCO3 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–0.9 M). 3890 optical unis of white solid were obtained (TEA salt; yield 53%).

7-methylguanosin-5′-yl monophosphate; m7GMP; (12)

GMP (TEA salt, 500 mg; 1.08 mmol) was dissolved in 12.5 cm3 of anhydrous DMSO and CH3I (0.6 cm3; 9.3 mmol) was added. The reaction was performed 3 for hours and quenched by addition of 150 cm3 of MQ water. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 using solid NaHCO3 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–0.7 M). 4935 optical unis of white solid were obtained (TEA salt; yield 40%).

2′-O-methylguanosin-5′-yl monophosphate; m2′-OGMP

2′-O-mG (1000 mg; 3.4 mmol) was suspended in 20 cm3 of trimethyl phosphate and the reaction flask was cooled in ice to 0°C. To a cold suspension POCl3 (0.638 cm, 6.8 mol,) was added, the reaction was performed for 2 hours and it was quenched via addition of 200 cm3 of MQ water. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 using NaHCO3 and the product was separated via ion-exchange chromatography (TEAB gradient 0–0.7 M). 1330 mg (TEA salt; yield 74%) of a white solid were obtained.

7,2′-O-dimethylguanosin-5′-yl monophosphate; m27,2′-OGMP; (14)

m2′-OGMP (TEA salt, 500 mg; 1.08 mmol) was dissolved in 12 cm3 of anhydrous DMSO and CH3I (0.6 cm3; 9.5 mmol) was added. The reaction was performed for 3 hours and quenched by addition of 150 cm3 of MQ water. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 using solid NaHCO3 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–0.7 M). 8500 optical unis of white solid were obtained (TEA salt; yield 70%).

guanosin-5′-yl 1,2 methylene-diphosphate; GpCH2p; (20)

Guanosine (250 mg, 0.883 mmol) was dissolved in 10 cm3 of trimethyl phosphate and cooled to 0 °C on an ice bath and methylenebis(phosphonic dichloride) (665 mg, 3.532 mmol) was added to the stirred mixture. The reaction was performed at 0 °C and after 90 minutes it was quenched by addition of 100 cm3 of MQ water, then solid NaHCO3 was added untill pH = 7. The product was purified via ion–exchange chromatography on DEAE-Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.0 M). 7115 optical units of white solid were obtained (TEA salt; yield 67%).

7-methylguanosin-5′-yl 1,2 methylene-diphosphate; m7GpCH2p; (13)

GpCH2p (TEA salt, 250 mg; 0.389 mmol) was dissolved in 4.2 cm3 of anhydrous DMSO and CH3I (0.2 cm3; 3.112 mmol) was added. The reaction was performed for 3 hours and quenched by addition of 50 cm3 of MQ water. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 using solid NaHCO3 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on on DEAE-Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.0 M). 2260 optical units of white solid were obtained (TEA salt; yield 51%).

guanosin-5′-yl monophosphate P-imidazolide; GMP-Im/Na+; (15)

Starting from GMP (TEA salt; 250 mg; 0.54 mmol) 221 mg of white solid was obtained (TEA salt; yield 95%).

1P-guanosin-5′-yl diphosphate P2-imidazolide; GDP-Im/Na+; (17)

Starting from GDP (TEA salt; 300 mg; 0.467 mmol) 250 mg of white solid was obtained (yield 98%).

1P-guanosin-5′-yl 1,2 methylene-diphosphate P2-imidazolide; GpCH2p-Im/Na+; (18)

Starting from GpCH2p (TEA salt; 150 mg; 0.234 mmol) 118 mg of white solid was obtained (TEA salt; yield 95%).

P1-(3′ (2′)-O-anthraniloyl-7-methylguanosin-5′-yl) P3-guanosin-5′-yl triphosphate; 3′ (2′)Ant-m7GpppG; (1)

Ant-m7GDP (TEA salt, 60 mg; 0.077 mmol), GMP-Im (sodium salt; 48 mg 0.115 mmol) and anhydrous ZnCl2 (125 mg, 0.93 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF. After 70 minutes the reaction was quenched via addition of solution of EDTA (400 mg, 1.19 mmol) in a water solution of NaHCO3 (200 mg, 2.38 mmol). In next step the pH was adjusted to 7 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.4 M). 760 optical units (yield 39%) of pale yellow solid were obtained. The product was purified on HPLC yielding 25.4 mg (NH4 salt; yield 34%).

isomer C2′ 1H NMR (ppm): 9.13 (1H, s, H8m7G), 7.99 (1H, s, H8G), 7.86 (1H, m, H6); 7.36 (1H, m, H4), 6.76 (1H, m, H3), 6.70 (1H, m, H5), 6.18(1H, d, JH1′-H2′=3.0 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.78 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.5 Hz, H1′G), 5.72 (1H, dd, JH1-H2′=3.0 Hz, JH2′-H3′=4.5 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.75 (1H, m, overlapped with HDO, H3′m7G), 4.61 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=5.5, JH2′-H3′=5.2, H2′G), 4.50–4.21 (6H, m, H4′G, H4′m7G, H5′G, H″G, H5′m7G, H5″m7G), 4.47 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=5.2, JH3′-H4′=2.1 H3′G), 4.07 (3H, s, N-CH3) 31P NMR (ppm): −10.59 (2P, m, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=19.5 Hz, Pα, Pγ), −22.26 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=19.5 Hz, Pβ). ESI MS: calcd: 920.11725 Found: 920.11565.

isomer C3′ 1H NMR (ppm): 9.21 (1H, s, H8m7G), 7.99 (1H, s, H8G), 7.86 (1H, m, H6), 7.36 (1H, m, H4), 6.80 (1H, m, H3), 6.70 (1H, m, H5), 6.10 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=6.0 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.78 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.5 Hz, H1′G), 5.51 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=5.1 Hz, JH3′-H4′=2.8 Hz, H3′m7G), 4.97 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′ =6.0 Hz, JH2′-H3′=5.1 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.66 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.61 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=5.5, JH2′-H3′=5.2, H2′G), 4.50–4.21 (6H, m, H4′G, H4′m7G(A), H5′G, H″G, H5′m7G, H5″m7G), 4.47 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=5.2, JH3′-H4′=2.1 H3′G), 4.09 (3H, s, N-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): −10.59 (2P, m, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=19.5 Hz, Pα, Pγ), −22.26 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=19.5 Hz, Pβ). ESI MS: calcd: 920.11725 Found: 920.11565.

P1-(2′-O-methyl-3′-O-anthraniloyl-7-methylguanosin-5′-yl) P3-guanosin-5′-yl triphosphate; Ant-m27,2′-OGpppG; (5)

Ant-m27,2′-OGMP (TEA salt, 32 mg; 0.06 mmol) and GDP-Im (sodium salt; 39 mg 0.072 mmol) and anhydrous ZnCl2 (90 mg, 0.67 mmol) were dissolved in 0.5 cm3 anhydrous DMF. After 90 minutes the reaction was quenched via addition of a solution of EDTA (185 mg, 0.55 mmol) in water solution of NaHCO3 (92 mg, 1.1 mmol). In the next step the pH was adjusted to 7 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.4 M). 1250 optical units (yield 83%) of pale yellow solid were obtained. The product was purified on HPLC yielding 15.4 mg (NH4 salt; yield 26%).

1H NMR (ppm): 9.20 (1H, s, H8m7G), 8.03 (1H, s, H8G), 7.84 (1H, m, H6), 7.38 (1H, m, H4), 6.81 (1H, m, H3), 6.71 (1H, m, H5), 6.10 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′)=5.5 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.78 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.5 Hz, H1′G), 5.60 (1H, t, JH2′-H3′=JH3′-H4′=3.2 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.66 (2H, m, H2′m7G, H4′m7G), 4.61 (1H, t, JH1′-H2′=5.5 JH2′-H3′=5.0 Hz, H2′G), 4.45 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=5.0, JH3′-H4′=3.4, H3′G), 4.42 (1H, s, H4′G), 4.30 (4H, m, H5′m7G, H5″m7G, H5′G, H5″G), 4.10 (3H, s, N-CH3), 3.47 (3H, s, O-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): −10.60 (2P, d, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=18.5 Hz, Pα, Pγ,), −22.19 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=18.5 Hz Pβ,). ESI MS: calcd: 934.1329 Found: 934.13275.

P1-(3′ (2′)-O-N-methylanthraniloyl-7-methylguanosin-5′-yl) P3-guanosin-5′-yl triphosphate; 3′ (2′)Mant-m7GpppG; (2)

Mant-m7GDP (TEA salt, 90 mg; 0.115 mmol), GMP-Im (sodium salt; 70 mg 0.168 mmol) and anhydrous ZnCl2 (180 mg, 1.34 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF. After 70 minutes the reaction was quenched via addition of a solution of EDTA (560 mg, 1.5 mmol) in a water solution of NaHCO3 (252 mg, 3 mmol). In the next step the pH was adjusted to 7 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.4 M). 1070 optical units (yield 36%) of pale yellow solid were obtained. The product was purified on HPLC yielding 19.4 mg (NH4 salt; yield 17%).

isomer C2′ 1H NMR (ppm): 9.12 (1H, s, H8m7G), 7.98 (1H, s, H8G), 7.87 (1H, m, H6), 7.42 (1H, m, H4), 6.68 (1H, m, H3), 6.61 (1H, m, H5), 6.16 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=2.7 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.77 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=4.2, H1′G), 5.65 (1H, m, H2′m7G), 4.65 (1H, m, H2′G), 4.58 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=5.2, JH3′-H4′=5.0 Hz, H3′m7G), 4.51 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.42–4.20 (5H, m, H4′G, H5″m7G, H5′m7G, H5″G, H5′G), 4.05 (3H, s, N-CH3), 2.74 (3H, s, N-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): −14.44 (2P, d, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=19.1 Hz, Pα, Pγ), −26.00 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=19.1 Hz, Pβ). ESI MS: calcd: 934.1329 Found: 934.13313.

isomer C3′ 1H NMR (ppm): 9.17 (1H, s, H8m7G), 7.98 (1H, s, H8G), 7.81 (1H, m, H6), 7.42 (1H, m, H4), 6.68 (1H, m, H3), 6.53 (1H, m, H5), 6.10 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.7 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.77 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=4.2, H1′G), 5.49 (1H, m, H3′m7G), 4.98 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=5.7 Hz, JH2′-H3′=5.2 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.65 (1H, m, H2′G), 4.47 (2H, m, H3′G, H4′m7G), 4.42–4.20 (5H, m, H4′G, H5″m7G, H5′m7G, H5″G, H5′G), 4.05 (3H, s, N-CH3), 2.82 (3H, s, N-CH3). 31P NMR (ppm): −14.44 (2P, d, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=19.1 Hz, Pα, Pγ), −26.00 (1P, d, JPβ-Pα(Pγ)=19.1 Hz, Pβ). ESI MS: calcd: 934.1329 Found: 934.13313.

P1-(3′ (2′)-O-N-methylanthraniloyl-7-methylguanosin-5′-yl) P3-guanosin-5′-yl 1–2 methylenetriphosphate; 3′ (2′)Mant-m7GpCH2ppG; (4)

Mant-m7GpCH2p (TEA salt, 59 mg; 0.075 mmol), GMP-Im (Na salt; 39 mg 0.075 mmol) and anhydrous ZnCl2 (80 mg, 0.6 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF. After 4 hours the reaction was quenched via addition of solution of EDTA (240 mg, 0.63 mmol) in a water solution of NaHCO3 (110 mg, 1.33 mmol). In the next step the pH was adjusted to 7 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.4 M). 460 optical units (yield 23%) of pale yellow solid were obtained. The product was purified on HPLC yielding 6.3 mg (NH4 salt; yield 8%).

isomer C2′ 1H NMR (ppm): 9.41 (1H, s, H8m7G), 8.00 (1H, s, H8G), 7.93 (1H, m, H6), 7.47 (1H, m, H4), 6.99 (1H, m, H3), 6.93 (1H, m, H5), 6.22 (1H, m, H1′m7G), 5.78 (1H, m, H1′G), 5.67 (1H, m, H2′m7G), 4.67 (1H, m, overlapped with HDO, H3′m7G), 4.62 (1H, m, H2′G), 4.52 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.48 (1H, m, H3′G), 4.39–4.20 (5H, m, H4′G, H5″m7G, H5′m7G, H5″G, H5′G), 4.05 (3H, s, N-CH3(m7G)), 2.74 (3H, s, N-CH3), 2.42 (2H, m, P-CH2-P). 31P NMR (ppm): 18.31 (1P, m, Pβ), 8.04 (1P, s. Pγ), −10.09 (1P, s, Pα). ESI MS: calcd: 932.15363 Found: 932.15324.

isomer C3′ 9.49 (1H, s, H8m7G), 8.02 (1H, s, H8G), 7.93 (1H, m, H6), 7.47 (1H, m, H4), 6.76 (1H, m, H5), 6.67 (1H, m, H3), 6.14 (1H, m, H1′m7G), 5.78 (1H, m, H1′G), 5.55 (1H, m, H3′m7G), 5.07 (1H, m, H2′m7G), 4.92 (1H, m, overlapped with HDO, H3′m7G), 4.62 (1H, m, H2′G), 4.52 (1H, m, H4′m7G), 4.48 (1H, m, H3′G), 4.39–4.20 (5H, m, H4′G, H5″m7G, H5′m7G), H5″G, H5′G), 4.05 (3H, s, N-CH3(m7G)), 2.82 (3H, s, N-CH3), 2.42 (2H, m, P-CH2-P). 31P NMR (ppm): 18.31 (1P, m, Pβ), 8.04 (1P, s. Pγ), −10.09 (1P, s, Pα). ESI MS: calcd: 932.15363 Found: 932.15324.

P1-(3′ (2′)-O-N-methylanthraniloyl-7-methylguanosin-5′-yl) P3-guanosin-5′-yl 2–3 methylenetriphosphate; 3′ (2′)Mant-m7GppCH2pG; (3)

Mant-m7GMP (TEA salt, 49 mg; 0.08 mmol), GpCH2p-Im (Na salt; 50 mg 0.08 mmol) and anhydrous ZnCl2 (110 mg, 0.8 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF. After 10 hours the reaction was quenched via addition of solution of EDTA (330 mg, 0.9 mmol) in a water solution of NaHCO3 (150 mg, 1.8 mmol). In the next step the pH was adjusted to 7 and the product was purified employing ion-exchange chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex (TEAB gradient 0–1.4 M). 675 optical units (yield 36%) of pale yellow solid were obtained. The product was purified on HPLC yielding 8.8 mg (NH4 salt; yield 12% (partially decomposed during lyophilisation).

isomer C2′ 1H NMR (ppm): 9.20 (1H, s, H8m7G), 8.01 (1H, s, H8(G)), 7.89 (1H, m, H6), 7.44 (1H, m, H4), 6.70 (1H, m, H3), 6.61 (1H, m, H5), 6.18 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=3.5 Hz, H1′m7G)), 5.72 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=4.7 Hz, H1′G), 5.64 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=5.2 Hz, JH2′-H3′=3.5 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.68 (1H, overlapped with HDO, H3′m7G) 4.62 (1H, dd, H2′G), JH1′-H2′=5.2 Hz, JH2′-H3′=4.5 Hz), 4.45 (1H, t, JH2′-H3′=JH3′-H4′=4.5 Hz, H3′G), 4.40–4.16 (6H, m, H4′G, H4′m7G, H5″m7G, H5′m7G, H5′G, H5″G), 4.06 (3H, s, N-CH3(m7G)), 2.73 (3H, s, N-CH3), 2.38 (2H, m, P-CH2-P, JCH2-P = 20.5 Hz). 31P NMR (ppm): 18.05 (1P, m, Pβ), 8.36 (1P, m. Pγ), −10.18 (1P, m, Pα). ESI MS: calcd: 932.15363. Found: 932.15313.

isomer C3′ 1H NMR (ppm): 9.24 (1H, s, H8m7G,), 8.01 (1H, s, H8(G)), 7.89 (1H, m, H6), 7.44 (1H, m, H4), 6.70 (1H, m, H3), 6.61 (1H, m, H5), 6.10 (1H, d, JH1′-H2′=5.9 Hz, H1′m7G), 5.74 (1H, d, JH1-H2′=5.2 Hz, H1′G), 5.48 (1H, dd, JH2′-H3′=4.7 Hz, JH3′-H4′=2.7 Hz, H3′m7G), 4.97 (1H, dd, JH1′-H2′=5.9 Hz, JH2′-H3′=4.7 Hz, H2′m7G), 4.62 (1H, dd, H2′(G), JH1′-H2′=5.2 Hz, JH2′-H3′=4.5 Hz), 4.49 (1H, s, H4′m7G), 4.45 (1H, t, JH2′-H3′=JH3′-H4′=4.5 Hz, H3′G), 4.40–4.16 (6H, m, H4′G, H5″m7G, H5′m7G, H5′G, H5″G), 4.06 (3H, s, N-CH3(m7G)), 2.79 (3H, s, N-CH3), 2.38 (2H, m, P-CH2-P, JCH2-P = 20.5 Hz). 31P NMR (ppm): 18.05 (1P, m, Pβ), 8.36 (1P, m. Pγ), −10.18 (1P, m, Pα). ESI MS: calcd: 932.15363. Found: 932.15313.

Spectroscopic measurements

General information

Methyl anthranilate (AntOMe) and methyl N-methylanthranilate (MantOMe) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich and used without further purification. All the solvents used were also purchased from Sigma–Aldrich and were either HPLC grade or the highest grade available. Water was deionized using a Simplicity 185 system produced by Millipore. The pH of solutions was adjusted with a phosphate buffer (PBS) (0.067 M) and confirmed using a JENWAY 3030 pH Meter calibrated with standard buffers. Typically 10 buffer solutions ranging from pH 5 to 9 were employed. Absorption spectra were recorded on a Cary 5000 UV-Vis-NIR Spectrophotometer (Varian Inc.) using 1 cm square quartz cuvettes. The entire spectra from 220 to 450 nm (in 0.5 nm steps) were employed to calculate the pKa values and the spectra of the individual ionic forms according to the previously used method67. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded using a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer (Varian Inc.), the cell-housing block of which was thermostated to 25 °C within 0.1 °C. The emission and excitation spectra of the samples were measured in a 1 cm × 0.4 cm cuvette at 25°C. The fluorescence spectra of the samples were measured using a suitable excitation wavelength and emission range in order to calculate the total area under the curve. Quantum yields were determined by comparing the integral intensity of the steady state emission spectra excited at a long-wave maximum of absorption (corrected for the refractive index of the solvent and absorbance) with quinine sulphate in 0.1 M sulphuric acid, using a quantum yield (QY) of 0.5767. The optical density of the samples at this excitation wavelength did not exceed 0.1. For the photostability study, time-based fluorescence steady-state measurements were acquired with the excitation slit opened to maximum.

Fluorescence lifetime measurements

For fluorescence lifetime measurements samples were excited at 340 nm. The excitation source was a PLS-340 sub-nanosecond pulsed LED (340 nm, optical pulse duration: 410 ps FWHM) driven by a PDL800-D driver. Intensity decays were collected by a time-domain technique using a FluoTime 200 lifetime fluorometer (PicoQuant, GmbH) equipped with an R3809U-50 microchannel plate photomultiplier (MCP-PMT, Hamamatsu), and a PicoHarp300 TCSPC module. Polarizers were set to magic angle conditions and the fluorescence was observed through a 100 mm focal length single grating emission monochromator (ScienceTech 9030). All the samples were prepared directly before measurements and the recordings were taken at a temperature of 20°C. The fluorescence lifetimes were calculated using the FluoFit software package (version 4.4). All fluorescence decay curves were fitted using a single exponential function. The analysis involved iterative reconvolution fitting of a sum of exponentials to the experimentally recorded decays:

| (1) |

where I(t) is the intensity at time t, αi is the amplitude of a single exponential component i, and τi is the lifetime of the component.

Biological assays employing eIF4E and DcpS

Human eIF4E68 and human DcpS69 were prepared as described previously. The protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically (ε280 = 52940 M−1 cm−1 and 30400 for eIF4E and DcpS, respectively). Fluorescence measurements were run on an LS-50B spectrofluorometer (Perkin-Elmer Co., Hellma, Germany) in a quartz semi-micro cuvette with optical lengths of 4 and 10 mm for absorption and emission, respectively. Mant-m7GpppG titrations were performed in 50 mM Hepes/KOH (pH 7.2), 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT at 20 °C by adding appropriate aliquots of the eIF4E solutions to 100 nM Mant-m7GpppG or MantOMe solution. DcpS-based kinetic assays were performed in 50 mM Tris/HCl, 200 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT (pH 7.2) at 20 °C. The reactions were initiated by addition of either 200 nM or 20 nM DcpS. Samples were excited at 260 nm and 361 nm and the fluorescence intensity was recorded at 360 and 446 nm when the substrate was m7GpppG or Mant-m7GpppG, respectively.

In vitro synthesis of RNAs

Capped RNAs were synthesised by in vitro transcription of plasmid pluc-A60 digested with NcoI, which yielded a capped RNA corresponding to the first 48 nt of firefly luciferase mRNA. All ribonucleotides were obtained in the presence of given cap analogues and 10 uCi/ul [α32-P] GTP (PerkinElmer) as described previously12. Reaction mixtures were extracted with phenol and chloroform; RNAs were separated from small-molecule impurities with NucAway spin columns (Ambion). The concentrations of RNAs were determined via measuring Cerenkov radiation in a scintillation counter (Beckman).

Decapping assays

His-tagged-GB-SpDcp1 and SpDcp2 were coexpressed in BL21(DE3)pLysS Escherichia coli cells from p-His-GB1 plasmids, which were generously donated by John Gross, UCSF. The enzymes were expressed and purified as described previously70. Capped 32P-labled oligonucleotides were subjected to digestion with GST-SpDcp1/2 at 37°C for 30 minutes in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8 at 25°C), 50 mM NH4Cl, 0.01% NP-40, 1 mM DTT and 5 mM MgCl2. Reactions were quenched by adding two volumes of Precipitation/Inactivation Buffer III (Ambion). RNAs were precipitated at −20°C overnight, collected by centrifugation at 13000 g at 4°C for 20 min, purified by washing in 70% ethanol and collected again by centrifugation at 9000 g at 4 °C for 5 min. The quantity of RNA in the precipitated samples was determined via measurement of Cerenkov radiation in a scintillation counter (Beckman). The samples were resuspended in Sequencing Gel Loading Buffer (Ambion) and denatured at 95°C for 5 min. RNA sequencing gels (10% polyacrylamide) were run at 45–70 W for 3.5 h on a Base Runner Nucleic Acid Sequencer apparatus (International Biotechnologies). Gels were fixed in 5% acetic acid, 5% methanol for 10–15 min, dried onto Whatman 3MM filter paper (Fisher Scientific), and exposed to Blue X-ray film (Kodak). The intensity of individual bands was quantified by analyzing scanned film using the QuantityOne program (BioRad).

Translation efficiency in RRL of luciferase mRNA capped in vitro

Capped and polyadenylated luciferase mRNAs synthesised by in vitro transcription of a dsDNA template which contained: SP6 promoter sequence of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, 5′UTR sequence of rabbit β-globin, the entire firefly luciferase ORF and a string of 31 adenosines. The in vitro transcription reaction mixture (40 ml) contained: SP6 transcription buffer (Fermentas), 0.7 mg of DNA template, 1 U/ml RiboLock Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Fermentas), 0.5 mM ATP/CTP/UTP and 0.1 mM GTP and 0.5 mM dinucleotide cap analogue (molar ratio cap analog:GTP 5:1). The reaction mixture was preincubated at 37 °C for 5 minutes before addition of SP6 RNA polymerase (Fermentas) to a final concentration of 1 U/ml and the reaction was continued for 45 minutes at 37 °C. After incubation, reaction mixtures were treated with DNase RQ1 (Promega), in transcription buffer, for 20 min at 37 °C at a concentration of 1U per 1 mg of DNA template. RNA transcripts were purified using NucAway Spin Columns (Ambion), the integrity of transcripts was checked on a non-denaturating 1% agarose gel and concentrations were determined via UV spectroscopy. A translation reaction in RRL was performed in 10 ml volume for 60 minutes at 30 °C, in conditions determined for cap dependent translation. The reaction mixture contained: 40% RRL lysate, mixture of amino acids (0.01 mM), MgCl2 (1.2 mM), potassium acetate (170mM) and 5′-capped mRNA. Four different concentrations of each analyzed transcript were tested in the translation reaction. The activity of synthesized luciferase was measured in a luminometer and the obtained data were processed using Origin 8 software (OriginLab).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Laboratory of Biological NMR (Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, IBB PAS) for access to the NMR apparatus; Joanna Kowalska for critical reading of the manuscript, valuable comments and discussion; Jacek Oledzki from the Laboratory of Mass Spectrometry (IBB PAS) for recording MS spectra; John D. Gross from the University of California, San Francisco for Dcp1 and Dcp2 plasmid, Joanna Zuberek for valuable discussion and gift of eIF4E sample and Malgorzata Zytek for help with recording emission spectra. This study was supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (N N204 089438, N N301 096339), National Science Centre, Poland (UMO-2012/05/E/ST5/03893), a grant R01GM20818 from the National Institutes of Health (U.S.A), and a scholarship from the Foundation for Polish Science International Ph.D. Projects Program and the EU European Regional Development Fund (M.Z.).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Furuichi Y, Shatkin AJ. Adv Virus Res. 2000;55:135–184. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(00)55003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemielity J, Kowalska J, Rydzik AM, Darzynkiewicz E. New Journal of Chemistry. 2010;34:829–844. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westman B, Beeren L, Grudzien E, Stepinski J, Worch R, Zuberek J, Jemielity J, Stolarski R, Darzynkiewicz E, Rhoads RE, Preiss T. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2005;11:1505–1513. doi: 10.1261/rna.2132505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konarska MM, Padgett RA, Sharp PA. Cell. 1984;38:731–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contreras R, Gheysen D, Knowland J, van de Voorde A, Fiers W. Nature. 1982;300:500–505. doi: 10.1038/300500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stepinski J, Waddell C, Stolarski R, Darzynkiewicz E, Rhoads RE. RNA. 2001;7:1486–1495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalek M, Jemielity J, Darzynkiewicz ZM, Bojarska E, Stepinski J, Stolarski R, Davis RE, Darzynkiewicz E. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:3223–3230. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grudzien-Nogalska E, Jemielity J, Kowalska J, Darzynkiewicz E, Rhoads RE. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2007;13:1745–1755. doi: 10.1261/rna.701307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kowalska J, Lewdorowicz M, Zuberek J, Grudzien-Nogalska E, Bojarska E, Stepinski J, Rhoads RE, Darzynkiewicz E, Davis RE, Jemielity J. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2008;14:1119–1131. doi: 10.1261/rna.990208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowalska J, Lukaszewicz M, Zuberek J, Darzynkiewicz E, Jemielity J. Chembiochem. 2009;10:2469–2473. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn AN, Diken M, Kreiter S, Selmi A, Kowalska J, Jemielity J, Darzynkiewicz E, Huber C, Tureci O, Sahin U. Gene Therapy. 2010;17:961–971. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su W, Slepenkov S, Grudzien-Nogalska E, Kowalska J, Kulis M, Zuberek J, Lukaszewicz M, Darzynkiewicz E, Jemielity J, Rhoads RE. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2011;17:978–988. doi: 10.1261/rna.2430711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rydzik AM, Kulis M, Lukaszewicz M, Kowalska J, Zuberek J, Darzynkiewicz ZM, Darzynkiewicz E, Jemielity J. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;20:1699–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haran G. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 2012;22:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao R, Rueda D. Methods. 2009;49:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flors C, Earnshaw WC. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung BO, Chou KC. Appl Spectrosc. 2011;65:967–980. doi: 10.1366/11-06398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henriques R, Griffiths C, Hesper Rego E, Mhlanga MM. Biopolymers. 2011;95:322–331. doi: 10.1002/bip.21586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahoo H. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews. 2011;12:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truong K, Ikura M. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 2001;11:573–578. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ha T, Tinnefeld P. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2012;63:595–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss S. Science. 1999;283:1676–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pareek CS, Smoczynski R, Tretyn A. J Appl Genet. 2011;52:413–435. doi: 10.1007/s13353-011-0057-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Sagheer AH, Brown T. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1388–1405. doi: 10.1039/b901971p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinkeldam RW, Greco NJ, Tor Y. Chemical reviews. 2010;110:2579–2619. doi: 10.1021/cr900301e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toseland CP, Webb MR. Methods. 2010;51:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiratsuka T, Katoh T. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31891–31894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto A. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5815–5828. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15025a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostergaard ME, Hrdlicka PJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5771–5788. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15014f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiratsuka T. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2003;270:3479–3485. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan MA, Goss DJ. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4510–4516. doi: 10.1021/bi047298g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagshaw C. Journal of cell science. 2001;114:459–460. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jameson DM, Eccleston JF. Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 1997;278:363–390. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)78020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geduhn J, Dove S, Shen YQ, Tang WJ, Konig B, Seifert R. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;336:104–115. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.174219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suryanarayana S, Wang JL, Richter M, Shen YQ, Tang WJ, Lushington GH, Seifert R. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2009;78:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goettle M, Dove S, Steindel P, Shen Y, Tang WJ, Geduhn J, Koenig B, Seifert R. Molecular Pharmacology. 2007;72:526–535. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen Y, Lee YS, Soelaiman S, Bergson P, Lu D, Chen A, Beckingham K, Grabarek Z, Mrksich M, Tang WJ. EMBO J. 2002;21:6721–6732. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gille A, Guo J, Mou TC, Doughty MB, Lushington GH, Seifert R. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;71:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinto C, Lushington GH, Richter M, Gille A, Geduhn J, Konig B, Mou TC, Sprang SR, Seifert R. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2011;82:358–370. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mou TC, Gille A, Fancy DA, Seifert R, Sprang SR. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7253–7261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emmrich T, El-Tayeb A, Taha H, Seifert R, Müller CE, Link A. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2010;20:232–235. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei CC, Balasta ML, Ren J, Goss DJ. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1910–1916. doi: 10.1021/bi9724570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren JH, Goss DJ. Nucleic Acids Research. 1996;24:3629–3634. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.18.3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zdanowicz A, Thermann R, Kowalska J, Jemielity J, Duncan K, Preiss T, Darzynkiewicz E, Hentze MW. Molecular Cell. 2009;35:881–888. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deshmukh MV, Jones BN, Quang-Dang DU, Flinders J, Floor SN, Kim C, Jemielity J, Kalek M, Darzynkiewicz E, Gross JD. Molecular Cell. 2008;29:324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mathonnet G, Fabian MR, Svitkin YV, Parsyan A, Huck L, Murata T, Biffo S, Merrick WC, Darzynkiewicz E, Pillai RS, Filipowicz W, Duchaine TF, Sonenberg N. Science. 2007;317:1764–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1146067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grudzien E, Kalek M, Jemielity J, Darzynkiewicz E, Rhoads RE. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1857–1867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalek M, Jemielity J, Grudzien E, Zuberek J, Bojarska E, Cohen LS, Stepinski J, Stolarski R, Davis RE, Rhoads RE, Darzynkiewicz E. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2005;24:615–621. doi: 10.1081/ncn-200060091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nawrot B, Sprinzl M. Nucleos Nucleot. 1998;17:815–829. doi: 10.1080/07328319808004677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nawrot B, Milius W, Ejchart A, Limmer S, Sprinzl M. Nucleic acids research. 1997;25:948–954. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]