The innate immune system is the primary line of defense against systemic fungal infections. As a result, the interaction between Candida albicans, the most important fungal pathogen in the developed world, and innate immune phagocytes has received significant attention as a key infection determinant, revealing complex transcriptional and developmental responses in both cell types. The availability of easily propagated macrophage-like cell lines and the remarkable morphological switch that occurs in phagocytosed C. albicans cells have made this an important model of host–pathogen interactions. Several lines of evidence have emerged that C. albicans actively resists recognition by the immune system and inhibits some of the classical antimicrobial responses. This Pearl will discuss recent findings in Candida–macrophage interactions.

Immune Recognition: A Taste of Something Sweet

Innate immune phagocytes, including macrophages, recognize C. albicans and other fungal pathogens via Pathogen Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs); the most important of these are the cell wall carbohydrates: mannan (as mannosylated proteins), β-glucan, and chitin, a minor component. The structure of these polysaccharides and the receptors to which they bind has been discussed in depth elsewhere [1], [2]. In C. albicans yeast cells, the β-glucan layer is obscured by the outer mannoproteins and largely inaccessible to the immune system [3]. To oversimplify, a greater proinflammatory response results from alterations that increase exposure of the inner β-glucans, including hypoxia [4], antifungal drugs [3], and inhibition of glycerophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchoring of the mannoproteins in the wall [5]. Some strain-specific differences in β-glucan–based recognition by the Dectin-1 receptor are apparent only in vivo but affect the outcome of the infection [4]; one could speculate that this represents active regulation of cell wall structure in vivo.

Deposition of complement proteins on the cell surface is both microbicidal and immunostimulatory. The C. albicans cell surface binds numerous negative regulators of the complement cascade to inhibit complement activation: Pra1 (pH-Regulated Antigen) binds plasminogen, Factor H, FHL-1, and C4B, all in active forms [6], [7]. At least eight proteins bind plasminogen to the C. albicans surface [8], and complement factors are substrates of the Secreted Aspartyl Protease family [9]. The sum of these activities is to reduce immune recognition of the fungal cell.

Stress Responses: Pleading Self-Defense

C. albicans is resistant to macrophage-associated stresses, including reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS). C. albicans encodes a catalase and six superoxide dismutases; unusually, three Sod enzymes (Sod4-6) are secreted and detoxify extracellular ROS produced by macrophages [10]. The single catalase (Cat1) does not have a signal sequence but has also been identified on the cell surface [8]. Thus, C. albicans blunts the antimicrobial respiratory burst before it can cause intracellular damage. Anti-RNS defenses are intracellular in the form of three flavohemoglobin enzymes (Yhb1, Yhb4, Yhb5); deletion of YHB1 renders cells hypersensitive to NO in vitro [11]. There is also evidence that a variety of fungi, including C. albicans, can inhibit NO production from macrophages, but no mechanism has been identified (see [12]).

A discrepancy exists, however, between in vitro and in vivo stress phenotypes. Mutation of the ROS-responsive Cap1 transcription factor confers profound sensitivity to oxidants and failure to filament within macrophages [13], [14]. Cap1 regulates catalase expression [15], as does the MAP kinase Hog1; both cat1Δ and hog1Δ have profound virulence defects in mice [16], [17]. Yet the cap1Δ mutant is fully virulent [18], suggesting additional Hog1- and Cap1-independent regulatory mechanisms, as proposed [19]. Similarly, mutation of Yhb1 has only mild effects on virulence, suggesting roles for other anti-NO mechanisms in vivo [11].

Nutritional Stress: The South Beach Diet

C. albicans cells phagocytosed by macrophages switch to a gluconeogenic growth mode [20]. The starvation-like response is specific to carbon metabolism and mutation of genes encoding key steps of gluconeogenesis; the glyoxylate cycle and β-oxidation of fatty acids attenuate virulence to a greater or lesser degree [21], [22]. Single cell GFP reporters confirm induction of genes such as phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK1) and isocitrate lyase (ICL1) in macrophages and in tissues [21]. The regulatory networks that control expression of these genes differ markedly from the S. cerevisiae paradigms [23].

What carbon sources are most relevant in vivo? Some host niches are clearly glucose-deficient. Lactate, produced by tissues and by bacteria in the gut, is one potential carbon source. Fungi generally prefer glucose to the exclusion of any other carbon sources, but C. albicans cells metabolize glucose and lactate concurrently in at least some circumstances [24]. Cells grown on lactate have an altered cell wall; are more resistant to osmotic, envelope, and antifungal stresses; and are more adherent [25]. Lactate-grown cells elicit lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines from monocytic cells but, once phagoctyosed, actually do more damage to macrophages [26]. Thus, exposure to nonpreferred carbon sources benefits C. albicans in its interactions with macrophages. It is likely that this flexible organism finds and uses multiple carbon sources within the host.

We have proposed that amino acids are another relevant in vivo nutrient [27]. Phagocytosed cells induce the entire arginine biosynthetic pathway but no other amino acid synthetic genes [20], [28]. Surprisingly, expression results from exposure to moderate concentrations of ROS, rather than a lack of arginine. Induction is not seen when phagocytosed by ROS-deficient macrophages lacking the gp91 subunit of the phagocyte oxidase [28]. The significance of this connection between nutrients and oxidative stress is not clear.

Intracellular Trafficking: Losing One's Way

We are beginning to understand the molecular interactions at the interface between host and pathogen cells that lead to endocytosis and the activation of responses in both cells. In contrast, the intracellular fate of C. albicans once phagocytosed remains a mystery. Early investigations came to contradictory conclusions about whether phagosome–lysosome fusion occurred, depending on the approach used. A more recent analysis using markers along the endocytic pathway during phagosome maturation demonstrated that intracellular trafficking of C. albicans is aberrant, but a definitive mapping of these events was obscured by heterogeneity in postendocytic events [29]. Relative to heat-killed controls, phagosomes with live C. albicans cells were associated with less filamentous actin and acquired late endosomal markers less robustly, including LAMP-1 and the vATPase proton pump. Even transient colocalization with late endosomal makers was rapidly lost and, in phagosomes containing filamentation-competent cells, replaced with elements normally associated with the ER membrane, such as calnexin. Live C. albicans appears to inhibit both lysosomal acidification and NO release [29]. We have also identified macrophage-like conditions in which C. albicans releases ammonia derived from amino acid degradation to raise extracellular pH [27], potentially synergizing with the vATPase defect to block acidification. On top of this, some phagocytosed C. albicans cells escape macrophages through a non-lytic route [30]; the underlying mechanisms, again, are not understood.

The take-home message is that the intracellular fate of live C. albicans differs markedly from that of killed cells, implying an active modulation by the fungal cell. At least some filamentous cells escape the normal phagocytic pathway to an “ER-like” compartment. Further study, particularly with more refined temporal resolution to reduce heterogeneity, is clearly needed to understand the intracellular fate of this organism.

Morphogenesis: The Shape of What's to Come

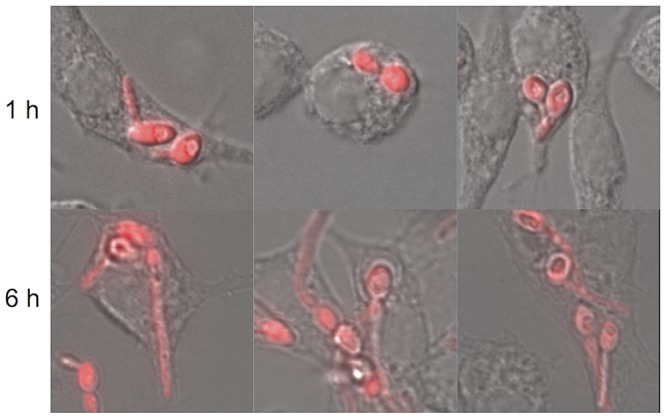

Morphological differentiation is a central theme of fungal pathogenesis, from the multicellular development of Aspergillus species to the hyphal-to-yeast transition in the host of the dimorphic fungi, such as Histoplasma and Coccidioides. C. albicans yeast cells germinate within the macrophage, forming hyphae that penetrate and kill the phagocyte, a remarkable aspect of this interaction (Figure 1). Yeast, hyphae, and pseudohyphae can be seen simultaneously in tissues, and this reversible switch is a core virulence trait, as mutants locked in one form are avirulent [31], [32]. The regulation of hyphal morphogenesis is extremely complex, with multiple inducing signals, including neutral pH, elevated CO2, serum, physiological temperatures, and N-acetylglucosamine, feeding into signaling pathways that culminate in dozens of transcription factors (reviewed in [33]).

Figure 1. Morphogenesis of C. albicans within macrophages.

C. albicans cells constitutively expressing yCherry were incubated for one hour (top) or six hours (bottom). Germination is apparent early and has disrupted macrophage structures by the later time point.

It is not clear why C. albicans switches to the hyphal form within the macrophage. The intracellular environment should be acidic and carbon-poor, which are conditions inhibitory to filamentous growth. The aberrant trafficking discussed above may put C. albicans in more conducive conditions, but what actually induces the transition is unknown. Two possibilities impinge on amino acid metabolism: Mutants lacking arg4Δ form hyphae less well than wild-type strains within macrophages, and it has been proposed that C. albicans cells synthesize and then degrade arginine for the purpose of generating CO2 [34], which is consistent with our demonstration that this pathway is induced [28]. More broadly, catabolism of amino acids as a carbon source in vitro releases ammonia as a byproduct, resulting in a dramatic rise in the extracellular pH, and we proposed that this occurs when in the macrophage [27]. ROS may also induce the hyphal switch, as cap1Δ mutants fail to filament after phagocytosis [14]. Either or both of these phenomena could create hyphal-inducing conditions in the macrophage.

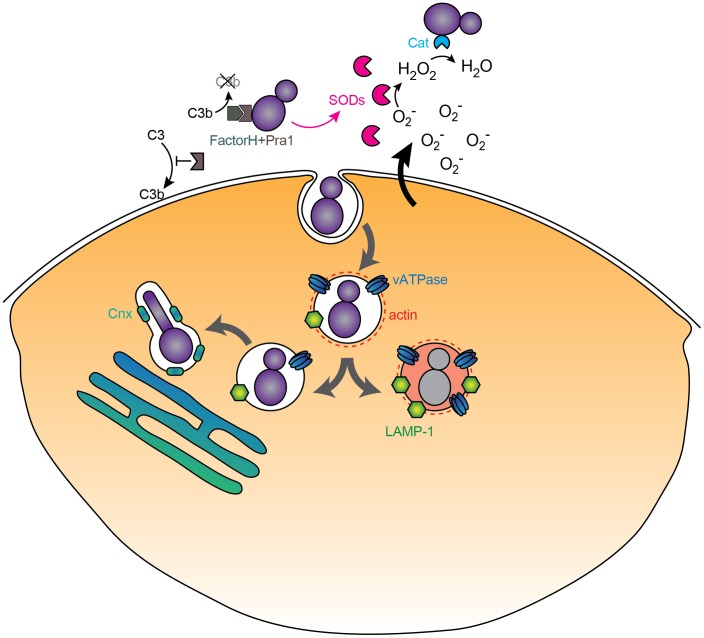

In summary, the C. albicans–macrophage model is a dynamic interaction in which this opportunistic pathogen employs multiple avenues to blunt the antimicrobial activity of the phagocyte by inhibiting recognition, trafficking, and effector release (Figure 2), while overcoming several important stresses. While much is left to learn, this is an important model system for understanding host–pathogen interactions.

Figure 2. Immunomodulatory activities of C. albicans.

Extracellular C. albicans inhibits complement deposition and detoxifies ROS via secreted mediators (SODs, catalase, Pra1), while phagocytosed cells proceed along an altered trafficking pathway to end up in an ER-associated compartment characterized by the membrane calnexin (Cnx) and a loss of LAMP-1, peripheral actin, and vATPase.

Funding Statement

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Public Health Service grant R01AI075091 to MCL. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Netea MG, Brown GD, Kullberg BJ, Gow NA (2008) An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol 6: 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perez-Garcia LA, Diaz-Jimenez DF, Lopez-Esparza A, Mora-Montes HM (2011) Role of cell wall polysaccharides during recongition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. J Glycobiology 1: 102. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wheeler RT, Fink GR (2006) A drug-sensitive genetic network masks fungi from the immune system. PLoS Pathog 2: e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marakalala MJ, Vautier S, Potrykus J, Walker LA, Shepardson KM, et al. (2013) Differential adaptation of Candida albicans in vivo modulates immune recognition by dectin-1. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003315 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McLellan CA, Whitesell L, King OD, Lancaster AK, Mazitschek R, et al. (2012) Inhibiting GPI anchor biosynthesis in fungi stresses the endoplasmic reticulum and enhances immunogenicity. ACS Chem Biol 7: 1520–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Luo S, Blom AM, Rupp S, Hipler UC, Hube B, et al. (2011) The pH-regulated antigen 1 of Candida albicans binds the human complement inhibitor C4b-binding protein and mediates fungal complement evasion. J Biol Chem 286: 8021–8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Luo S, Poltermann S, Kunert A, Rupp S, Zipfel PF (2009) Immune evasion of the human pathogenic yeast Candida albicans: Pra1 is a Factor H, FHL-1 and plasminogen binding surface protein. Mol Immunol 47: 541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crowe JD, Sievwright IK, Auld GC, Moore NR, Gow NA, et al. (2003) Candida albicans binds human plasminogen: identification of eight plasminogen-binding proteins. Mol Microbiol 47: 1637–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gropp K, Schild L, Schindler S, Hube B, Zipfel PF, et al. (2009) The yeast Candida albicans evades human complement attack by secretion of aspartic proteases. Mol Immunol 47: 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frohner IE, Bourgeois C, Yatsyk K, Majer O, Kuchler K (2009) Candida albicans cell surface superoxide dismutases degrade host-derived reactive oxygen species to escape innate immune surveillance. Mol Microbiol 71: 240–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ullmann BD, Myers H, Chiranand W, Lazzell AL, Zhao Q, et al. (2004) Inducible defense mechanism against nitric oxide in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 3: 715–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Collette JR, Lorenz MC (2011) Mechanisms of immune evasion in fungal pathogens. Curr Opin Microbiol 14: 668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alarco AM, Raymond M (1999) The bZip transcription factor Cap1p is involved in multidrug resistance and oxidative stress response in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol 181: 700–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patterson MJ, McKenzie CG, Smith DA, da Silva Dantas A, Sherston S, et al. (2013) Ybp1 and Gpx3 Signaling in Candida albicans Govern Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidation of the Cap1 Transcription Factor and Macrophage Escape. Antioxid Redox Signal E-pub ahead of print. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Znaidi S, Barker KS, Weber S, Alarco AM, Liu TT, et al. (2009) Identification of the Candida albicans Cap1p regulon. Eukaryot Cell 8: 806–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alonso-Monge R, Navarro-Garcia F, Molero G, Diez-Orejas R, Gustin M, et al. (1999) Role of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1p in morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol 181: 3058–3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wysong DR, Christin L, Sugar AM, Robbins PW, Diamond RD (1998) Cloning and sequencing of a Candida albicans catalase gene and effects of disruption of this gene. Infect Immun 66: 1953–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jain C, Pastor K, Gonzalez AY, Lorenz MC, Rao RP (2013) The role of Candida albicans AP-1 protein against host derived ROS in in vivo models of infection. Virulence 4: 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gonzalez-Parraga P, Alonso-Monge R, Pla J, Arguelles JC (2010) Adaptive tolerance to oxidative stress and the induction of antioxidant enzymatic activities in Candida albicans are independent of the Hog1 and Cap1-mediated pathways. FEMS Yeast Res 10: 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lorenz MC, Bender JA, Fink GR (2004) Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot Cell 3: 1076–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barelle CJ, Priest CL, Maccallum DM, Gow NA, Odds FC, et al. (2006) Niche-specific regulation of central metabolic pathways in a fungal pathogen. Cell Microbiol 8: 961–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Piekarska K, Mol E, van den Berg M, Hardy G, van den Burg J, et al. (2006) Peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation is not essential for virulence of Candida albicans . Eukaryot Cell 5: 1847–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ramirez MA, Lorenz MC (2009) The transcription factor homolog CTF1 regulates {beta}-oxidation in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 8: 1604–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sandai D, Yin Z, Selway L, Stead D, Walker J, et al. (2012) The evolutionary rewiring of ubiquitination targets has reprogrammed the regulation of carbon assimilation in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. MBio 3: e00495–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ene IV, Adya AK, Wehmeier S, Brand AC, MacCallum DM, et al. (2012) Host carbon sources modulate cell wall architecture, drug resistance and virulence in a fungal pathogen. Cell Microbiol 14: 1319–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ene IV, Cheng SC, Netea MG, Brown AJ (2013) Growth of Candida albicans cells on the physiologically relevant carbon source lactate affects their recognition and phagocytosis by immune cells. Infect Immun 81: 238–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vylkova S, Carman AJ, Danhof HA, Collette JR, Zhou H, et al. (2011) The Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans Autoinduces Hyphal Morphogenesis by Raising Extracellular pH. MBio 2: e00055–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jimenez-Lopez C, Collette JR, Brothers KM, Shepardson KM, Cramer RA, et al. (2013) Candida albicans induces arginine biosynthetic genes in response to host-derived reactive oxygen species. Eukaryot Cell 12: 91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fernandez-Arenas E, Cabezon V, Bermejo C, Arroyo J, Nombela C, et al. (2007) Integrated proteomics and genomics strategies bring new insight into Candida albicans response upon macrophage interaction. Mol Cell Proteomics 6: 460–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bain JM, Lewis LE, Okai B, Quinn J, Gow NA, et al. (2012) Non-lytic expulsion/exocytosis of Candida albicans from macrophages. Fungal Genet Biol 49: 677–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lo HJ, Kohler JR, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, et al. (1997) Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90: 939–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saville SP, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL (2003) Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryot Cell 2: 1053–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Biswas S, Van Dijck P, Datta A (2007) Environmental sensing and signal transduction pathways regulating morphopathogenic determinants of Candida albicans. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71: 348–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghosh S, Navarathna DH, Roberts DD, Cooper JT, Atkin AL, et al. (2009) Arginine-induced germ tube formation in Candida albicans is essential for escape from murine macrophage line RAW 264.7. Infect Immun 77: 1596–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]