Abstract

AIM: To examine the efficacy of telbivudine (LdT) + adefovir (ADV) vs continuation of lamivudine (LAM) + ADV in patients with LAM-resistant chronic hepatitis B (CHB) who show a suboptimal response to LAM + ADV.

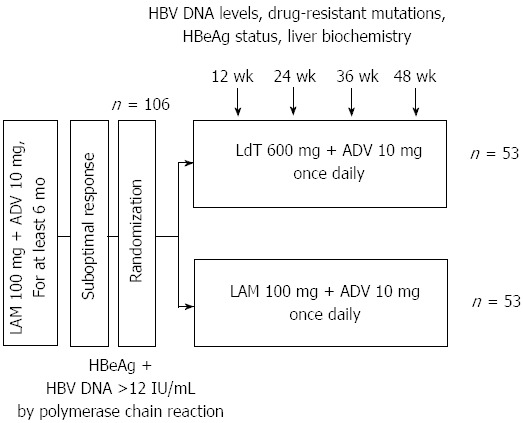

METHODS: This was a randomized, active-control, open-label, single-center, parallel trial. All eligible patients were enrolled in this study in Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea, between March 2010 and March 2011. Hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg)-positive CHB patients whose serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA remained detectable despite at least 6 mo of LAM + ADV therapy were included. Enrolled patients were randomized to either switching to LdT (600 mg/d orally) plus ADV (10 mg/d orally) (LdT + ADV group) or to continuation with LAM (100 mg/d orally) plus ADV (10 mg/d orally) (LAM + ADV group), and were followed for 48 wk. One hundred and six patients completed the 48-wk treatment period. Serum HBV DNA, HBeAg status, liver biochemistry and safety were monitored at baseline and week 12, 24, 36 and 48.

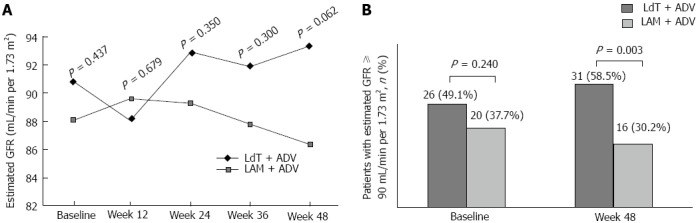

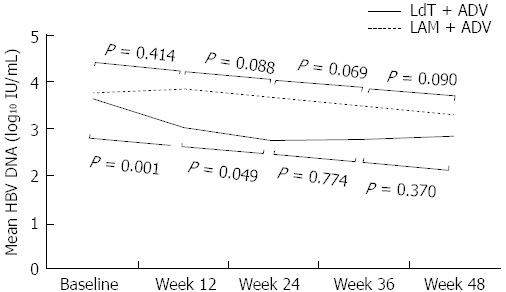

RESULTS: The duration of prior LAM + ADV treatment was 18.3 (LdT + ADV) and 14.9 mo (LAM + ADV), respectively (P = 0.131). No difference was seen in baseline serum HBV DNA between the two groups [3.66 (LdT + ADV) vs 3.76 (LAM + ADV) log10 IU/mL, P = 0.729]. At week 48, although there was no significant difference in the mean reduction of serum HBV DNA from baseline between LdT + ADV group and LAM + ADV group (-0.81 vs -0.47 log10 IU/mL, P = 0.167), more patients in the LdT + ADV group had undetectable HBV DNA levels compared to those in the LAM + ADV group (30.2% vs 11.5%, P = 0.019). Three patients with LdT + ADV treatment and 2 patients with LAM + ADV treatment achieved HBeAg loss. The patients in both groups tolerated the treatment well without serious adverse events. The proportion of patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥ 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the LdT + ADV group increased from 49.1% (26/53) at baseline to 58.5% (31/53) at week 48, while that in the LAM + ADV group decreased from 37.7% (20/53) at baseline to 30.2% (16/53) at week 48.

CONCLUSION: The switch to LdT + ADV in suboptimal responders to LAM + ADV showed a significantly higher rate of virologic response at week 48. These results suggest that LdT + ADV could be a therapeutic option for patients who are unable to use enofovir disoproxil fumarate for any reason.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis B, Antiviral resistance, Suboptimal response, Telbivudine, Lamivudine

Core tip: A suboptimal response is common in patients treated with lamivudine (LAM) + adefovir (ADV) combination therapy and it has also become a new challenge for the management of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients. We commenced this study with the effect of telbivudine (LdT) + ADV combination therapy as a rescue therapeutic option in LAM-resistant CHB patients with suboptimal response to LAM + ADV. Our results demonstrated that switching from LAM + ADV to LdT + ADV resulted in superior virologic response, renoprotective effect and similar safety profiles at week 48. These results suggest that LdT + ADV could be a therapeutic option for patients who are unable to use enofovir disoproxil fumarate for any reason.

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, over 400 million people suffer from chronic hepatitis B (CHB). Patients with CHB have a 15%-40% life-time risk of developing cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1,2]. High hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA concentration in serum in patients with CHB is known as an independent risk factor for disease progression to cirrhosis and HCC[2,3]. Therefore, the treatment goal of antiviral therapy for CHB is to achieve complete suppression of viral replication as rapidly as possible[4-6], because prolonged viremia on therapy can lead to a higher risk of future antiviral drug resistance and therapeutic failure as well as disease progression[2,7,8].

Lamivudine (LAM) has been widely used for treatment of CHB since its first approval at 2002. However, a major limitation of LAM is the development of LAM-resistant YMDD-motif mutations in the viral DNA polymerase, the prevalence of which increases progressively to about 70% after 4 years of treatment[9]. In patients resistant to LAM, add-on combination therapy with LAM and adefovir (ADV) has resulted in lower rates of virologic breakthrough and additional development of genotypic resistance than when switching to ADV or entecavir[10,11]. Thus, LAM + ADV combination therapy has been recommended as a rescue therapy in patients with LAM resistant viral strains in many Asian countries, for its considerable effectiveness, lower resistance and affordable price[5].

Unfortunately, a substantial proportion of patients treated with LAM + ADV combination therapy show a suboptimal virologic response[10-12]. Because there has been evidence that this suboptimal response to antiviral therapy might have clinical relevance to higher risk of developing resistance to long-term antiviral treatment, suboptimal response to nucleotide analogues (NAs), in addition to drug resistance, has also become a new challenge for the management of CHB patients[13-15]. However, there is no standard optimal strategy for the management of suboptimal response to NA therapy at present. Many practice guidelines suggest a combination treatment regimen with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) which is a NA with a high barrier to resistance as a highly potent rescue therapeutic option[4,6]. TDF, however, remains largely unavailable in Asian countries. Thus, several trials with various combination regimens for these populations have been proceeded[16,17], and the results suggested consistently that combination therapy rather than switching to another drug offers a potentially attractive therapeutic option.

Telbivudine (LdT) is one of the licensed NAs which is structurally related to LAM and highly selective for HBV DNA and inhibits viral DNA synthesis with no effect on human DNA or other viruses[18]. The Gestation Linked to Obesity and Environment (GLOBE), the largest trial in CHB, demonstrated that LdT is superior to LAM for all efficacy measures over 2 years of therapy[19,20]. Another trial showed a superior viral suppressive effect of LdT even to ADV in treatment naïve CHB patients[21]. In addition, LDT + ADV combination treatment showed better outcomes against LAM-resistant HBV than ADV alone[22]. Therefore, LdT is a therapeutic option in LAM-resistant hepatitis B patients with suboptimal response to LAM + ADV combination therapy.

In this study, we directly compared the antiviral efficacy of switching to LdT + ADV combination vs LAM + ADV continuation in hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) positive LAM-resistant hepatitis B patients who showed suboptimal response to LAM + ADV combination treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients eligible for this study were men and women, aged over 20 years, positive for serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for at least 6 mo, and positive for HBeAg. Inclusion criteria were confirmed mutations in the HBV polymerase gene that confers resistance to LAM (rtM204V/I and/or rtL180M), and serum HBV DNA concentration > 12 IU/mL after combination treatment with LAM (100 mg/d) plus ADV (10 mg/d) for at least 6 mo that was ongoing at the time of randomization. Patients were expected to have well-preserved liver function (Child-Pugh score ≤ 6) and no history of ascites, variceal bleeding, or encephalopathy.

Patients were excluded if they had previous or current HCC; prior treatment with an antiviral agent other than LAM and/or ADV; coinfection with hepatitis C, hepatitis D, or human immune deficiency virus; concurrent systemic corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents; history of alcohol or substance abuse; or other current liver diseases, prior organ transplantation, or a history of malignancy within 3 years.

Study design

This was a randomized, active-control, open-label, single-center, parallel trial. All eligible patients were enrolled in this study in Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, between March 2010 and March 2011. Patients were randomized to either switching to LdT (600 mg/d orally) plus ADV (10 mg/d orally) (LdT + ADV group) or to continuation with LAM (100 mg/d orally) plus ADV (10 mg/d orally) (LAM + ADV group), and were followed for 48 wk. Randomized patients were evaluated at baseline and week 12, 24, 36 and 48. At each visit, hematology, biochemistry, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio were assessed. HBV DNA level was measured at baseline and week 12, 24, 36 and 48, using a real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction assay (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) with a linear dynamic detection range of 12 to 1 × 109 IU/mL. Multiplex Restriction fragment mass polymorphism (RFMP) assays of the HBV genome were performed to detect LAM and ADV resistance mutations at baseline and at times as needed[23]. Because over 98% of South Korean patients with CHB have HBV genotype C[24,25], HBV genotype was not determined. HBeAg and anti-HBeAb were assessed at baseline and at week 48, using commercially available enzyme immunoassays (Abbott Laboratories)[26,27]. The upper limit of normal (ULN) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was defined as 40 IU/L. Occurrences of adverse events were assessed at every visit through week 48.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice as well as local regulatory requirements. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University of Medical College, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01270165 (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01270165).

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients in each treatment group who achieved virologic response (serum HBV DNA concentration of < 12 IU/mL) at week 48. Secondary endpoints included mean reduction from baseline in serum HBV DNA concentration at week 48, the proportion of patients with normalized serum ALT levels, HBeAg loss or seroconversion at week 48, and emergence of resistance mutation to drug during study period.

Statistical analysis

The variables were expressed as mean with SD or ranges, or n (%), as appropriate. The χ2 or Fisher’s exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Paired related data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon paired test. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of patients

One hundred and ten patients were screened from March 2010 to March 2011, and 106 were randomized (53 in each group). All patients completed 48 wk of treatment after randomization; thus, data from all 106 patients randomized were available for the intention-to-treat analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study participants. LMA: Lamivudine; ADV: Adefovir; LdT: Telbivudine; HBV: High hepatitis B virus; HBeAg: Hepatitis Be antigen.

Overall baseline characteristics of all patients as well as of each group are shown in Table 1. Twenty-four (22.6%) patients had cirrhosis with well-preserved liver function. The mean (SD) serum HBV DNA levels was 3.71 (1.46) log10 IU/mL. The mean (ranges) duration of LAM + ADV treatment prior to randomization was 17.1 (6-45) mo. At baseline, all patients had LAM resistance mutations, including 27 (25.5%) with rtM204I alone, 1 (0.9%) with rtM204I + rtM204V, 28 (26.4%) with rtM204I + rtL180M, 28 (26.4%) with rtM204V + rtL180M and 22 (20.8%) with rtM204I + rtM204V + rtL180M. There were no genotypic mutations of ADV in all patients at the baseline. Demographic and laboratory characteristics were similar between the two treatment groups, and mean (SD) serum HBV DNA levels in the LdT + ADV group and LAM + ADV group were 3.66 (1.65) log10 IU/mL and 3.76 (1.25) log10 IU/mL, respectively (P = 0.729). There was no difference in the mean duration of prior LAM treatment as well as that of LAM + ADV treatment prior to randomization between the two groups (prior LAM period, 31.5 mo vs 33.5 mo, P = 0.695; LAM + ADV period prior to randomization, 18.3 mo vs 14.9 mo, P = 0.131).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients n (%)

| Variables | Total (n = 106) | LdT + ADV (n = 53) | LAM + ADV (n = 53) | P value |

| Mean age, yr | 46.3 (22-76) | 49.0 (23-76) | 43.7 (22-73) | 0.053 |

| Male | 79 (74.5) | 42 (79.2) | 37 (69.8) | 0.265 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 24 (22.6) | 13 (24.5) | 11 (20.8) | 0.647 |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| AST (IU/L) | 29 (7-119) | 33 (7-119) | 28 (10-92) | 0.125 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 28 (13-125) | 26 (15-84) | 29 (13-125) | 0.098 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | 0.8 (0.3-1.6) | 0.382 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.5 (0.7-5.4) | 4.4 (3.4-5.4) | 4.6 (0.7-5.1) | 0.777 |

| Prothrombin time | 1.01 (0.91-1.42) | 1.00 (0.91-1.42) | 1.02 (0.93-1.24) | 0.917 |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 175 (45-293) | 175 (67-290) | 174 (45-293) | 0.610 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 2.87 (0.86-57.54) | 2.61 (1.57-11.66) | 2.98 (0.86-57.54) | 0.030 |

| Mean prior LAM period, mo (range) | 32.2 (8-139) | 31.5 (8-77) | 33.5 (11-139) | 0.695 |

| Mean prior LAM + ADV period, mo (range) | 17.1 (6-45) | 18.3 (6-45) | 14.9 (6-39) | 0.131 |

| YMDD mutation | 106 (100) | 53 (100) | 53 (100.0) | - |

| rtM204I alone | 27 (25.5) | 13 (24.5) | 14 (26.4) | 0.643 |

| rtM204I + rtM204V | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| rtM204I + rtL180M | 28 (26.4) | 15 (28.4) | 13 (24.5) | |

| rtM204V + rtL180M | 28 (26.4) | 12 (22.6) | 16 (30.2) | 0.501 |

| rtM204I + rtM204V + rtL180M | 22 (20.8) | 12 (22.6) | 10 (18.9) | 0.514 |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) | 89.1 (56.1-131.6) | 89.8 (59.8-131.6) | 85.7 (56.1-123.3) | 0.437 |

| Serum HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL) | 0.729 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.71 (1.46) | 3.66 (1.65) | 3.76 (1.25) | |

| Median (range) | 3.63 (1.32-8.10) | 3.34 (1.32-8.10) | 3.78 (1.41-5.94) |

Data expressed as mean (SD), mean (range) or median (range). ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; LAM: Lamivudine; ADV: Adefovire; HBV: High hepatitis B virus; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; LdT: Telbivudine.

Virologic response

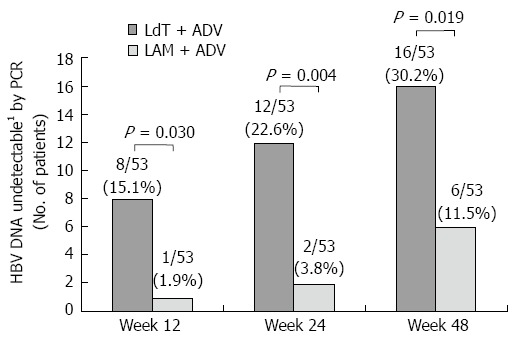

The efficacy of treatment in the LdT + ADV and LAM + ADV groups are summarized and compared in Table 2 and Figures 2, 3 and 4. During treatment, the number of patients who achieved virologic response (serum HBV DNA level of < 12 IU/mL) gradually increased to 16 (30.2%) patients at week 48 in the LdT + ADV group. In contrast, the number of patients with virologic response in the LAM + ADV group was consistently lower than those in the LdT + ADV group from week 12 to week 48, and only 6 (11.5%) patients in the LAM + ADV group showed virologic response at week 48. The primary efficacy endpoint, the proportion of patients who achieved HBV DNA level of < 12 IU/mL at week 48, differed significantly between the two groups (30.2 % vs 11.5 %, respectively, P = 0.019) (Figure 2 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Virologic, serologic and biochemical responses during study periods n (%)

| Variables |

Week 12 |

P value |

Week 24 |

P value |

Week 48 |

P value | |||

| LdT + ADV | LAM + ADV | LdT + ADV | LAM + ADV | LdT + ADV | LAM + ADV | ||||

| Serum HBV DNA, mean (SD) (log10 IU/mL) | 3.05 (1.51) | 3.84 (1.35) | 0.011 | 2.79 (1.52) | 3.65 (1.44) | 0.003 | 2.85 (1.73) | 3.29 (1.49) | 0.168 |

| Reductions in HBV DNA1, mean (SD) (log10 IU/mL) | -0.68 (0.83) | 0.07 (0.60) | < 0.001 | -0.88 (1.06) | -0.11 (0.85) | < 0.001 | -0.81 (1.43) | -0.47 (1.04) | 0.167 |

| HBV DNA undetectable2 | 8 (15.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0.030 | 12 (22.6) | 2 (3.8) | 0.004 | 16 (30.2) | 6 (11.5) | 0.019 |

| Virologic nonresponders3 | - | - | - | 33 (62.3) | 48 (90.6) | 0.001 | - | - | - |

| HBsAg loss | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| HBeAg negativity, | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) | - | 3 (5.7) | 2 (3.8) | 0.648 |

| Normal range of ALT4 | 39 (73.6) | 38 (71.7) | 0.828 | 37 (69.8) | 40 (75.5) | 0.513 | 40 (75.5) | 38 (71.7) | 0.768 |

| ALT normalization5 | 2/14 (14.3) | 6/14 (42.9) | 0.209 | 6/14 (42.9) | 5/14 (35.7) | 0.704 | 8/14 (57.1) | 3/14 (21.4) | 0.053 |

Reduction of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA from baseline;

Defined serum HBV DNA of < 12 IU/mL;

Defined as a < 1 log10 IU/mL reduction in serum HBV DNA level from baseline at 24 wk;

Upper normal limit of ALT, 40 IU/L;

Among patients who have elevated ALT levels at baseline. ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; LAM: Lamivudine; ADV: Adefovir. HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg: Hepatitis Be antigen.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with undetectable serum hepatitis B virus DNA (< 12 IU/mL) over time. 1Undetectable < 12 IU/mL. LAM: Lamivudine; ADV: Adefovire; HBV: High hepatitis B virus; LdT: Telbivudine; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

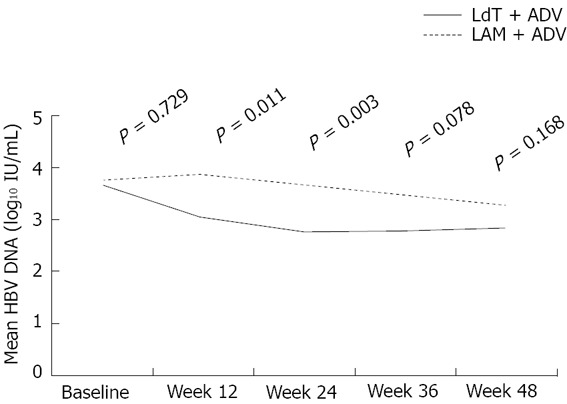

Figure 3.

Mean hepatitis B virus DNA levels over time in the two groups. LAM: Lamivudine; ADV: Adefovire; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; LdT: Telbivudine.

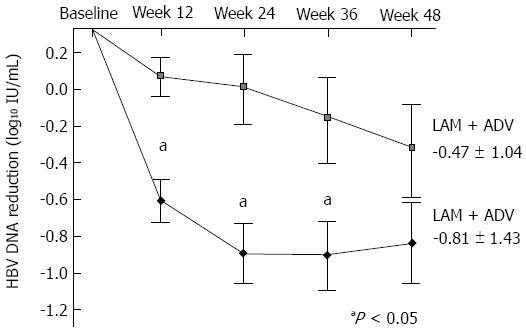

Figure 4.

Mean reduction of serum hepatitis B virus DNA levels from baseline. Mean hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA (log10 IU/mL) were plotted over time. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (aP value < 0.05). LAM: Lamivudine; ADV: Adefovire; LdT: Telbivudine.

Mean (SD) serum HBV DNA level of the LdT + ADV group was significantly lower than that of the LAM + ADV group at week 12 and week 24 [3.05 (1.51) log10 IU/mL vs 3.84 (1.35) log10 IU/mL at week 12, P = 0.011; 2.79 (1.52) log10 IU/mL vs 3.65 (1.44) log10 IU/mL at week 24, P = 0.003] (Table 2 and Figure 3). However, there was no statistically significant difference in serum HBV DNA levels between the LdT + ADV group and the LAM + ADV group [2.85 (1.73) log10 IU/mL vs 3.29 (1.49) log10 IU/mL at 48 wk, P = 0.168] (Figure 3).

The mean reduction of serum HBV DNA levels from baseline to week 12 or week 24 was significantly greater in the LdT + ADV than in the LAM + ADV group (-0.68 log10 IU/mL vs 0.07 log10 IU/mL; P < 0.001, -0.88 log10 IU/mL vs -0.11 log10 IU/mL; P < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 4 and Table 2). At week 48, however, there was no significant difference in the mean reduction of serum HBV DNA from baseline between the LdT + ADV group and the LAM + ADV group (-0.81 log10 IU/mL vs -0.47 log10 IU/mL, P = 0.167; Table 2 and Figure 4).

The number of patients with virologic nonresponse, defined as < 1 log10 IU/mL reduction in serum HBV DNA level from baseline at week 24, was significantly lower in the LdT + ADV group than in the LAM + ADV group [33 (62.3%) vs 48 (90.6%), respectively, P = 0.001] (Table 2). A total of 8 patients experienced virologic breakthrough (≥ 1 log10 IU/mL increase in serum HBV DNA from nadir during treatment), 4 patients in the LdT + ADV group and 4 patients in the LAM + ADV group. Most of them (6/8) had poor compliance for taking medication, and there was no new emergence of drug resistance for LAM or ADV in the RFMP examination conducted at the time of virologic breakthrough.

Biochemical and serologic response

The proportion of patients with normal serum ALT levels at week 48 did not differ significantly between the LdT + ADV group and the LAM + ADV group (75.5% vs 71.7%, respectively; P = 0.768) (Table 2). Among patients with elevated ALT at baseline, the proportion of patients achieving normalized ALT at week 48 in the LdT + ADV group and LAM + ADV group were 57.1% (8/14) and 21.4% (3/14), respectively, and the difference showed borderline significance between the two groups (P = 0.053) (Table 2).

Three patients (5.7%) in the LdT + ADV group and 2 patients (3.8%) in the LAM + ADV group became HBeAg negative at week 48 (P = 0.648; Table 2). No patient achieved loss of HBsAg during the treatment period.

Safety

The majority of patients in the LdT + ADV and LAM + ADV groups tolerated the treatment well without serious adverse events. No patient required dose reduction or discontinuation of treatment due to an adverse event. No patient experienced ALT flare (> 10 × ULN), increased serum creatinine kinase level of > 150 U/L, or serum phosphorus level of < 1.5 mg/dL during the treatment period. Neither group reported decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma from baseline to week 48.

No patient was found to have an elevation of creatinine ≥ 0.5 mg/dL. The mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is shown in Figure 5A. Although statistical significance did not exist, eGFR in the LdT + ADV group tended to increase during the treatment period, whereas that in the LAM + ADV group tended to decrease. The proportion of patients with eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the LdT + ADV group increased from 49.1% (26/53) at baseline to 58.5% (31/53) at week 48, while that in the LAM + ADV group decreased from 37.7% (20/53) at baseline to 30.2% (16/53) at week 48. The proportion of patients with eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was significantly higher in the LdT + ADV group than in the LAM + ADV group at week 48 (58.5% vs 30.2%; P = 0.003) (Figure 5B). Twenty-six percent (7/27) of the patients with baseline eGFR < 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 shifted to eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 after 48 wk of LdT + ADV treatment, as compared to 15.2% (5/33) in the LAM + ADV group (P = 0.299).

Figure 5.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate over time in the two groups (A), and proportion of patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥ 90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 at baseline and week 48 (B). LAM: Lamivudine; ADV: Adefovire; HBV: High hepatitis B virus; LdT: Telbivudine. GFR: Glomerular filtration rate

DISCUSSION

This study is the first study that provides a direct comparison of the antiviral efficacy of LdT + ADV and LAM + ADV in HBeAg-positive LAM resistant CHB patients who have suboptimal response to LAM + ADV. The results of this study show that treatment with LdT + ADV significantly suppressed HBV replication and more patients with LdT + ADV achieved virologic response compared to those with LAM + ADV after 48 wk of treatment. The difference in viral suppressive effect between the two groups was greatest at week 24, which decreased gradually thereafter.

The combination of LAM and ADV has been recommended as a treatment option for patients with LAM resistant CHB[4-6]. Because of the unavailability of TDF in many Asian countries, ADV has been used widely as a combination treatment regimen. However, due to the weak antiviral activity of ADV[28] and poor susceptibility for drug-resistant viral strains, suboptimal response is particularly common in patients who received LAM + ADV[29,30]. Evidence has shown that the persistence of suboptimal response during long-term antiviral treatment is associated with the emergence of multi-drug resistant viral strains, which could result in poorer clinical outcomes[31,32]. Thus, management of a suboptimal response to antiviral therapy has recently been of new concern, and combination with other NAs rather than switching to monotherapy offers a potentially attractive therapeutic option[33,34].

Based on the superior efficacy of LdT over LAM shown in the GLOBE trial[35], a recent study examined switching patients who remained viremic under LAM treatment to LdT and demonstrated that early (≤ 24 wk) switch to LdT improves virologic outcomes in CHB patients with persistent viral replication under LAM treatment[36]. In addition, previous two independent short-term studies on patients with poor response to ADV monotherapy demonstrated that a higher proportion of patients in the LdT + ADV group achieved a virological response at week 24 than did patients in the LAM + ADV group[37,38]. Based on these prior reports, we conducted this study to investigate the efficacy of switching to LdT + ADV as a substitute therapeutic option for patients who showed a suboptimal response to LAM + ADV combination treatment.

In our study, patients who were switched to LdT + ADV had a superior virologic response at 48 wk compared to those who continued LAM + ADV treatment (30.2% vs 11.5%, P = 0.019). At 48 wk, the mean serum HBV DNA level was lower and the mean reduction from baseline was greater in the LdT + ADV group than in the LAM + ADV (2.85 log10 IU/mL vs 3.29 log10 IU/mL and -0.81 log10 IU/mL vs -0.47 log10 IU/mL, respectively), but the differences between the two groups were not statistically significant (P = 0.168 and P = 0.167, respectively). As described in Table 2, however, differences of both the mean serum HBV DNA levels and the mean reduction of HBV DNA levels from baseline were significant at 12 wk and 24 wk. These results are ascribable to a different rate of decline in serum HBV DNA levels between the two groups. When we analyzed the rate of decline between adjacent time points in the respective treatment groups, we found that there were no statistically significant declines of serum HBV DNA levels as times go by in the LAM + ADV group (Figure 6). Continuing LAM + ADV with suboptimal response offers little antiviral benefit to patients with LAM-resistant HBV and as much as 90.6% of patients who continued on LAM + ADV remained as virologic non-responders (defined as < 1 log10 IU/mL reduction in baseline serum HBV DNA level at 24 wk) at week 24. In contrast, serum HBV DNA levels decreased significantly not only from baseline to 12 wk but also from 12 wk to 24 wk in the LdT + ADV group (P < 0.001 and P = 0.049, respectively) (Figure 6). This suggests that the viral suppressive effect emerged in the LdT + ADV group particularly during the early treatment period.

Figure 6.

Serial changes of mean serum hepatitis B virus DNA levels. Serum hepatitis B virus DNA levels decreased significantly not only from baseline to 12 wk but also from 12 wk to 24 wk in the LdT + ADV group. LAM: Lamivudine; ADV: Adefovire; HBV: High hepatitis B virus; LdT: Telbivudine.

Considering the significantly decreased serum HBV DNA level in the LdT + ADV group during the early treatment period, we speculated the good virologic response in this group may be related to the effect of LdT, because evidence in treatment-naïve patients demonstrates that LdT could significantly increase the rate of virologic response compared to LAM as well as ADV[19,39,40]. However, the rate of serum HBV DNA level decline in the LdT + ADV group decreased and became dull at the later part of the study period, which is from week 24 to week 48. It might be correlated to diminished susceptibility to NAs and generally unsatisfying clinical outcomes in a pretreated population with drug-resistant HBV compared to a treatment-naïve population[41-43]. Another possible explanation is that the emergence of ADV-resistant HBV strains following suboptimal response to LAM + ADV might attenuate the superior viral suppressive effect of LdT to that of LAM in these study patients. This is supported by a recent study which reported no differences in virologic and biochemical responses in the comparison of two treatments, LdT + ADV and LAM + ADV, in CHB patients with suboptimal response to ADV monotherapy[44].

HBeAg loss is the key goal of antiviral therapy for HBeAg-positive CHB patients, which indicates good prognosis, including lower rates of cirrhosis and slower disease progression[5,6,45,46]. In our study, we reported quite low rates of HBeAg loss, with 5.7% in the LdT + ADV group and 3.8% in the LAM + ADV group, suggesting that this pretreated population is particularly refractory to serologic response. It has been reported that HBeAg loss is less common in patients with LAM-resistant mutation than in those with wild-type HBV, regardless of the adequate rescue therapy[41-43].

Both treatments were well tolerated and showed similar safety profiles. Patients who switched from LAM + ADV to LdT + ADV did not experience any additional spectrum of adverse effects. Interestingly, we found that the patients in the LdT + ADV group showed a favorable effect of improved renal function compared to those in the LAM + ADV group during the treatment period. Although the mechanism has not been clarified, there have been several reports that LdT treatment is associated with renoprotective effects in patients with CHB[47,48]. Considering the risk of renal impairment of ADV, the renoprotective effect of LdT could be complementary in patients who were treated with ADV for a long term period.

There are some limitations in this study. First, this prospective study has small sample size and a potential bias. Relatively short follow-up duration was another limitation. Thus, further well controlled studies with sufficient size and longer duration of follow-up are needed.

In conclusion, this trial demonstrated that switching from LAM + ADV to LdT + ADV in LAM-resistant CHB patients with suboptimal response resulted in superior virologic response, renoprotective effect and similar safety profiles at week 48. These results suggest that CHB patients with LAM-resistant HBV and suboptimal response to LAM + ADV treatment should be considered for switching to other combination regimens using more potent drugs. LdT + ADV could be a therapeutic option for patients who are unable to use TDF for any reason. However, a stronger rescue combination therapy should be investigated in this population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Liver Cirrhosis Clinical Research Center, a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R and D project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, South Korea (HI10C2020), and a grant to the Bilateral International Collaborative R and D Program from the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, Republic of Korea. The authors are grateful to Dong-Su Jang (Medical Illustrator, Medical Research Support Section, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea) for his help with the figures. The authors are grateful to Dong-Su Jang (Medical Illustrator, Medical Research Support Section, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea) for his help with the figures.

COMMENTS

Background

A substantial proportion of patients treated with lamivudine (LAM) + adefovir (ADV) combination therapy show a suboptimal virologic response. Because there has been evidence that this suboptimal response to antiviral therapy might have clinical relevance to higher risk of developing resistance to long-term antiviral treatment, suboptimal response to nucleotide analogues, in addition to drug resistance, has also become a new challenge for the management of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients. However, there is no standard optimal strategy for the management of suboptimal response to nucleotide analogue therapy at present.

Research frontiers

This study is the first study that provides a direct comparison of the antiviral efficacy of telbivudine (LdT) + ADV and LAM + ADV in hepatitis Be antigen-positive LAM resistant CHB patients who have suboptimal response to LAM + ADV.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Our results demonstrated that switching from LAM + ADV to LdT + ADV in LAM-resistant CHB patients with suboptimal response resulted in superior virologic response, renoprotective effect and similar safety profiles at week 48.

Applications

From our study, it was suggested that LdT + ADV could be a therapeutic option for patients who are unable to use tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for any reason.

Peer review

The authors described a comparison of combination therapy of telbivudine plus adefovir vs lamivudine plus adefovir. This is the first comparison study about these 2 different combination therapies. This information is very important for future antiviral therapy of chronic B hepatitis. Furthermore, the study design is well organized and data is analyzed very well.

Footnotes

Supported by The Liver Cirrhosis Clinical Research Center, a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R and D project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, South Korea, No. HI10C2020; and a grant to the Bilateral International Collaborative R and D Program from the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, South Korea

P- Reviewer: Yoshida S S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:97–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, Huang GT, Iloeje UH. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Chen CJ. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:678–686. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, Guan R, Lau GK, Locarnini S. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:263–283. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Fong DY, Fung J, Wong DK, Yuen JC, But DY, Chan AO, Wong BC, Mizokami M, et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gish RG. Improving outcomes for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:14–22. doi: 10.1007/s11894-008-0016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NW, Atkins M, Hunt C, Brown N, Woessner M, Boehme R, Condreay L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:687–696. doi: 10.1086/368083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lampertico P, Viganò M, Manenti E, Iavarone M, Sablon E, Colombo M. Low resistance to adefovir combined with lamivudine: a 3-year study of 145 lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1445–1451. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapti I, Dimou E, Mitsoula P, Hadziyannis SJ. Adding-on versus switching-to adefovir therapy in lamivudine-resistant HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:307–313. doi: 10.1002/hep.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heo NY, Lim YS, Lee HC, Chung YH, Lee YS, Suh DJ. Lamivudine plus adefovir or entecavir for patients with chronic hepatitis B resistant to lamivudine and adefovir. J Hepatol. 2010;53:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampertico P. Partial virological response to nucleos(t)ide analogues in naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B: From guidelines to field practice. J Hepatol. 2009;50:644–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santantonio T, Fasano M, Durantel S, Barraud L, Heichen M, Guastadisegni A, Pastore G, Zoulim F. Adefovir dipivoxil resistance patterns in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:557–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallego A, Sheldon J, García-Samaniego J, Margall N, Romero M, Hornillos P, Soriano V, Enrĺquez J. Evaluation of initial virological response to adefovir and development of adefovir-resistant mutations in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:392–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xing J, Han T, Liu L, Li Y, Li J, Li Y, Xiao SX. Entecavir 1.0mg monotherapy or entecavir plus adefovir dipivoxil for patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B had suboptimal response to lamivudine plus adefovir dipivoxil. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2011;19:828–832. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim YS, Lee JY, Lee D, Shim JH, Lee HC, Lee YS, Suh DJ. Randomized trial of entecavir plus adefovir in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B who show suboptimal response to lamivudine plus adefovir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2941–2947. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00338-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant ML, Bridges EG, Placidi L, Faraj A, Loi AG, Pierra C, Dukhan D, Gosselin G, Imbach JL, Hernandez B, et al. Antiviral L-nucleosides specific for hepatitis B virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:229–235. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.229-235.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, Hsu CW, Thongsawat S, Wang Y, Chen Y, Heathcote EJ, Rasenack J, Bzowej N, et al. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2576–2588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keeffe EB, Zeuzem S, Koff RS, Dieterich DT, Esteban-Mur R, Gane EJ, Jacobson IM, Lim SG, Naoumov N, Marcellin P, et al. Report of an international workshop: Roadmap for management of patients receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:890–897. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan HL, Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Lai CL, Cho M, Moon YM, Chao YC, Myers RP, Minuk GY, Jeffers L, et al. Treatment of hepatitis B e antigen positive chronic hepatitis with telbivudine or adefovir: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:745–754. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn SH, Kweon YO, Paik SW, Sohn JH, Lee KS, Kim DJ, Piratvisuth T, Yuen MF, Chutaputti A, Chao YC, et al. Telbivudine in combination with adefovir versus adefovir monotherapy in HBeAg-positive, lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2011:Oct 12; Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s12072-011-9314-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han KH, Hong SP, Choi SH, Shin SK, Cho SW, Ahn SH, Hahn JS, Kim SO. Comparison of multiplex restriction fragment mass polymorphism and sequencing analyses for detecting entecavir resistance in chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:77–87. doi: 10.3851/IMP1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bae SH, Yoon SK, Jang JW, Kim CW, Nam SW, Choi JY, Kim BS, Park YM, Suzuki S, Sugauchi F, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype C prevails among chronic carriers of the virus in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:816–820. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.5.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim BK, Revill PA, Ahn SH. HBV genotypes: relevance to natural history, pathogenesis and treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:1169–1186. doi: 10.3851/IMP1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chon YE, Kim SU, Lee CK, Heo J, Kim JK, Yoon KT, Cho M, Lee KS, Kim DH, Choi EH, et al. Partial virological response to entecavir in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:469–477. doi: 10.3851/IMP1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JM, Ahn SH, Kim HS, Park H, Chang HY, Kim do Y, Hwang SG, Rim KS, Chon CY, Han KH, et al. Quantitative hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B e antigen titers in prediction of treatment response to entecavir. Hepatology. 2011;53:1486–1493. doi: 10.1002/hep.24221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, de Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JM, Park JY, Kim do Y, Nguyen T, Hong SP, Kim SO, Chon CY, Han KH, Ahn SH. Long-term adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy for up to 5 years in lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:235–241. doi: 10.3851/IMP1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryu HJ, Lee JM, Ahn SH, Kim do Y, Lee MH, Han KH, Chon CY, Park JY. Efficacy of adefovir add-on lamivudine rescue therapy compared with switching to entecavir monotherapy in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1835–1842. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghany MG, Doo EC. Antiviral resistance and hepatitis B therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:S174–S184. doi: 10.1002/hep.22900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locarnini S. Molecular virology and the development of resistant mutants: implications for therapy. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25 Suppl 1:9–19. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reijnders JG, Pas SD, Schutten M, de Man RA, Janssen HL. Entecavir shows limited efficacy in HBeAg-positive hepatitis B patients with a partial virologic response to adefovir therapy. J Hepatol. 2009;50:674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunetto MR, Lok AS. New approaches to optimize treatment responses in chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2010;15 Suppl 3:61–68. doi: 10.3851/IMP1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liaw YF, Gane E, Leung N, Zeuzem S, Wang Y, Lai CL, Heathcote EJ, Manns M, Bzowej N, Niu J, et al. 2-Year GLOBE trial results: telbivudine Is superior to lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:486–495. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safadi R, Xie Q, Chen Y, Yin YK, Wei L, Hwang SG, Zuckerman E, Jia JD, Lopez P. Efficacy of switching to telbivudine in chronic hepatitis B patients treated previously with lamivudine. Liver Int. 2011;31:667–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang LC, Chen EQ, Cao J, Liu L, Wang JR, Lei BJ, Tang H. Combination of Lamivudine and adefovir therapy in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients with poor response to adefovir monotherapy. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:178–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen EQ ZT, Tang H. Combination of telbivudine and adefovir dipivoxil therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with poor response to adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy. INT J INFECT DIS. 2010;14 Suppl 2:S18. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKeage K, Keam SJ. Telbivudine: a review of its use in compensated chronic hepatitis B. Drugs. 2010;70:1857–1883. doi: 10.2165/11204330-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartwell D, Jones J, Harris P, Cooper K. Telbivudine for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13 Suppl 3:23–30. doi: 10.3310/hta13suppl3/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang TT, Gish RG, Hadziyannis SJ, Cianciara J, Rizzetto M, Schiff ER, Pastore G, Bacon BR, Poynard T, Joshi S, et al. A dose-ranging study of the efficacy and tolerability of entecavir in Lamivudine-refractory chronic hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1198–1209. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters MG, Hann Hw Hw, Martin P, Heathcote EJ, Buggisch P, Rubin R, Bourliere M, Kowdley K, Trepo C, Gray Df Df, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:91–101. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherman M, Yurdaydin C, Sollano J, Silva M, Liaw YF, Cianciara J, Boron-Kaczmarska A, Martin P, Goodman Z, Colonno R, et al. Entecavir for treatment of lamivudine-refractory, HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2039–2049. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen EQ, Zhou TY, Bai L, Wang JR, Yan LB, Liang LB, Tang H. Lamivudine plus adefovir or telbivudine plus adefovir for chronic hepatitis B patients with suboptimal response to adefovir. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:973–979. doi: 10.3851/IMP2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liaw YF. HBeAg seroconversion as an important end point in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:425–433. doi: 10.1007/s12072-009-9140-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn SH, Chan HL, Chen PJ, Cheng J, Goenka MK, Hou J, Lim SG, Omata M, Piratvisuth T, Xie Q, et al. Chronic hepatitis B: whom to treat and for how long? Propositions, challenges, and future directions. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:386–395. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9163-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X, Zhong C, Yang S, Fan R, Peng J, Guo Y, Sun J, Hou J. [Influence of adefovir dipivoxil or telbivudine monotherapy on renal function of patients with chronic hepatitis B] Nanfang Yike Daxue Xuebao. 2012;32:826–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gane E, Deray G, Piratvisuth T, Chan HLY, Jia J, Ren H, Rasenack J, Manns M, Amarapurkar D, Dong Y, et al. Renal function of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients improves with telbivudine treatment[R] Thailand, Bangkok: APASL; 2011. [Google Scholar]