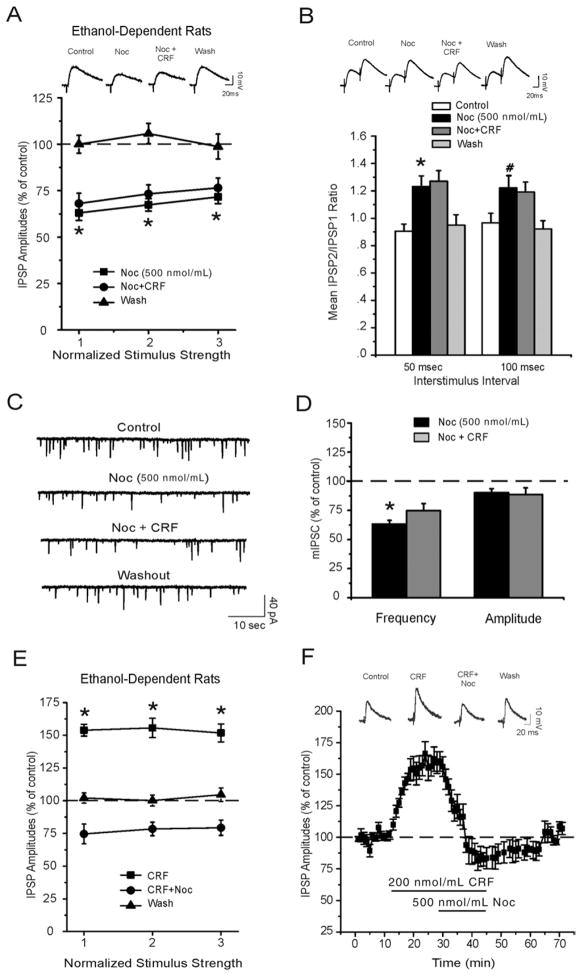

Figure 4.

The effects of the nociceptin (Noc)–corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) interaction are enhanced in ethanol-dependent rats. (A) Top panel: evoked inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) from an ethanol-dependent rat. Bottom panel: Noc (500 nmol/mL) significantly (*p < .01) decreases mean IPSP amplitudes and prevents enhancement of IPSPs induced by subsequent application of CRF (200 nmol/mL). (B) Top panel: Representative recordings of evoked paired-pulse IPSPs in a central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) neuron. Bottom panel: Noc significantly increases the mean 50- and 100-msec PPF ratio of IPSPs (*p < .01; #p < .05). Application of CRF after Noc does not alter paired-pulse facilitation ratio. (C) Representative traces of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) from neurons of ethanol-dependent rats. (D) Mean ± SEM frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs for CeA neurons from ethanol-dependent rats. Noc significantly (*p < .01) decreased the mean mIPSC frequency. Subsequent coapplication of CRF did not alter mIPSC frequency. (E) Superfusion of CRF alone significantly (*p < .01) increases mean IPSP amplitudes. Subsequent application of Noc reverses CRF-induced facilitation of evoked IPSP amplitude. (F) Top panel: representative recordings of evoked CeA IPSPs from an ethanol-dependent rat. Bottom panel: time course depicting changes in IPSP amplitude evoked by CRF, concurrent application of CRF and Noc (n = 6), and washout of the two peptides.