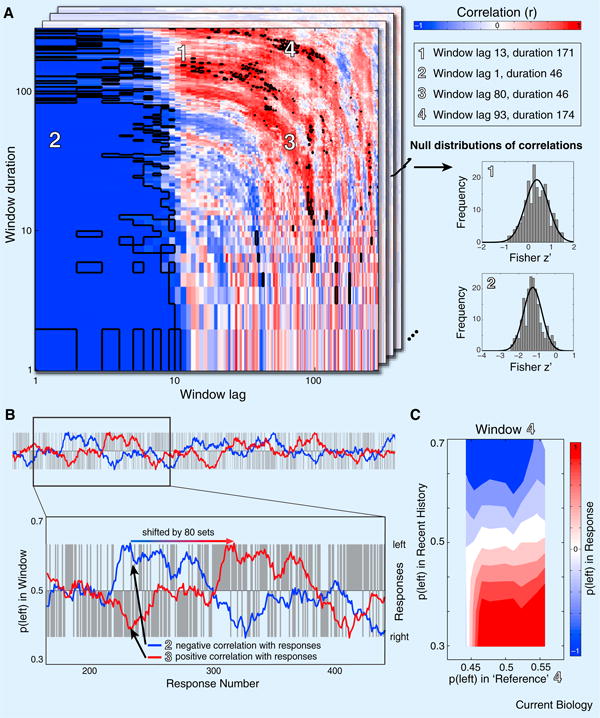

Figure 1.

A short-term negative aftereffect can produce seeming capture of responses by long-term stimulus history. (A) Correlations between responses of simulated observers and stimulus windows of varying durations and lags lead to remarkably similar results as human observers in [3]. Signifcant correlations are indicated by black outlines. Repeating this simulation many times generates a null distribution for correlations expected from just a negative aftereffect (shown for two example windows on the right; also see Supplemental Figure S2). (B) Simulated timecourses of responses (gray bars) and stimuli in a sliding average window (blue, 2 in A). Because of the short-term aftereffect, responses are negatively correlated with the averaged stimulus timecourse. Increasing the window's lag (red, 3 in A) relative to the responses can turn these negative correlations to positive. (C) Simulated responses as a function of stimuli in the recent history and a selected ‘reference window’ (4 in A). A positive relationship between reference window and responses (as shown for a selected window in Figure 3 of [3]) can occur by chance due to noise in the observer.