Abstract

1,1-Bis(3-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl)methane (C-DIM) compounds exhibit remarkable antitumor activity with low toxicity in various cancer cells including lung tumors. Two C-DIM analogs, DIM-C-pPhOCH3 (C-DIM-5) and DIM-C-pPhOH (C-DIM-8) while acting differentially on the orphan nuclear receptor, TR3/Nur77 inhibited cell cycle progression from G0/G1 to S-phase and induced apoptosis in A549 cells. Combinations of docetaxel (doc) with C-DIM-5 or C-DIM-8 showed synergistic anticancer activity in vitro and these results were consistent with their enhanced antitumor activities in vivo. Respirable aqueous formulations of C-DIM-5 (mass median aerodynamic diameter of 1.92 ± 0.22 um and geometric standard deviation of 2.31 ± 0.12) and C-DIM-8 (mass median aerodynamic diameter of 1.84 ± 0.31 um and geometric standard deviation of 2.11 ± 0.15) were successfully delivered by inhalation to athymic nude mice bearing A549 cells as metastatic tumors. This resulted in significant (p<0.05) lung tumor regression and an overall reduction in tumor burden. Analysis of lung tumors from mice treated with inhalational formulations of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 showed decreased mRNA and protein expression of mediators of tumor initiation, metastasis, and angiogenesis including MMP2, MMP9, c-Myc, β-catenin, c-Met, c-Myc, and EGFR. Microvessel density assessment of lung tissue sections showed significant reduction (p<0.05) in angiogenesis and metastasis as evidenced by decreased distribution of immunohistochemical staining of VEGF, and CD31. Our studies demonstrate both C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 have similar anticancer profiles in treating metastatic lung cancer and possibly work as TR3 inactivators.

Keywords: Nur77/TR3, metastatic, nebulizer, angiogenesis, inhalation

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Studies have underscored the anticancer and/or antitumor activities of 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM), a metabolite of the naturally-occurring indole-3-carbinol (I3C) found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli (Chen et al., 2012; Shorey et al., 2012). The anticancer activity of DIM has been investigated in various cell lines including prostate, breast, and colon (Abdelbaqi et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Lerner et al., 2012). Further, DIM has been shown to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HCT-116, SW480, and HT-29 colon cancer cells (Choi et al., 2009; Lerner et al., 2012). 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl)methanes (C-DIMs) are synthetic analogs of DIM that exhibit structure-dependent activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) receptor (p-trifluoro, p-tert-butyl, p-cyano, and p-phenyl analogs), and the orphan receptor Nur77/TR3 (unsubstituted and p-methoxy analogs) (Cho et al., 2010, 2008, 2007; Guo et al., 2010; Ichite et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009; Lei et al., 2008a, 2008b; Safe et al., 2008; Yoon et al., 2011). In addition, the 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-hydroxyphenyl)methane analog (DIM-C-pPhOH) deactivates TR3 (Lee et al., 2011a, 2010). Nur77/TR3 (NR4A1) is a member of the NR4A family of receptors which also include Nurr1 (NR4A2) and Nor1 (NR4A3). These orphan nuclear receptors were initially identified as intermediate-early genes induced by nerve growth factor in PC12 cells (Milbrandt, 1988). Endogenous ligands for NR4A receptors have not been identified and these receptors are widely distributed in many organs including skeletal muscles, heart, liver, kidney and brain where they modulate various physiological and pathological processes (Maxwell and Muscat, 2006; McMorrow and Murphy, 2011; Safe et al., 2011). TR3 is a pro-oncogenic factor in various cancer cells where knockdown of TR3 results in cell growth inhibition, induction of apoptosis, and decreased angiogenesis (Kolluri et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2011a, 2010; Safe et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2008).

DIM-C-pPhOCH3 (C-DIM-5) and DIM-C-pPhOH (C-DIM-8) have been recognized as prototypical activators and deactivators of TR3 respectively (Cho et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2011b, 2010; Safe et al., 2011; Yoon et al., 2011). C-DIM-5 has been used as a prototypical activator of TR3 in transactivation assays using GAL4-TR3/GAL4-response element reporter gene assay system; however subsequent studies with GAL4-TR3 (human) showed minimal transactivation by C-DIM-5. C-DIM-5 induces a nuclear TR3-dependent apoptosis in pancreatic and colon cancer cells (Cho et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009). C-DIM-8 blocked the activation of TR3 in pancreatic, bladder, and lung cancer cells resulting in growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis and the results were similar to that observed after TR3 knockdown by RNAi (Lee et al., 2011b, 2010).

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 9 out of 10 lung cancer cases (Whitehead et al., 2003). Success of treatment of NSCLC however, is plagued by low efficacy and toxicity of drugs as well as development of tumor resistance. Localized delivery of aerosolized drugs to the lungs ensures delivery of optimum drug concentrations at target tissue and the enhanced potential of inhalation drug delivery for lung cancer treatment has been demonstrated using aerosolized 9-nitrocamptothecin, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (Wittgen et al., 2007). We hypothesize that inhalation delivery of the TR3 activator C-DIM-5 and the TR3 deactivator C-DIM-8 along with intravenous (i.v.) administration of docetaxel (doc) will provide an enhanced antitumor activity in NSCLC. In this study, we investigated the feasibility of aerosolizing C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 for evaluating their anticancer activities alone and in combination with doc in a metastatic mouse lung tumor model.

2.0 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Cell lines and Reagents

C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 were synthesized as described (Chintharlapalli et al., 2005). The Mouse Cancer PathwayFinder RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array was from SABiosciences (Valencia, CA) and Trizol reagent was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit was procured from Pierce (Rockford, IL). TR3, β-actin, MMP2, MMP9, rabbit anti-mouse antibody and secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA.). CD31, VEGFR2, p21, survivin, PARP, cleaved-PARP, cleaved caspase3, cleaved caspase8, Bcl2, and NFk-β, β-catenin, c-Met, c-Myc, and EGFR primary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). A549 cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). A549 cells were maintained in F12K medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin/neomycin at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 under a humidified atmosphere. The cell line throughout culture and during the duration of the study was periodically tested for the presence of mycoplasma by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Cells used for the study were between 5 to 20 passages. All other chemicals were of either reagent or tissue culture grade.

2.2 In-vitro cytotoxicity against A549 Cells

The in vitro cytotoxicity of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 alone and in combination with doc was evaluated in A549 cell line as previously reported (Chougule et al., 2011; Patlolla et al., 2010). A549 (104 cells/well) cells was seeded in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 hrs. The cells were treated with concentrations of doc, C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 or DMSO. The effects of doc in combination with C-DIM-5 or C-DIM-8 were also carried out and cell viability in each treatment group was determined at the end of 24 hrs by the crystal violet dye assay (Ichite et al., 2009). The interactions between doc and C-DIM-5 or C-DIM-8 were evaluated by isobolographic analysis by estimating the combination index (CI) as described (Luszczki and Florek-Łuszczki, 2012). Hence, a CI>1 indicates antagonism; CI=1 indicates additive effect; and a CI<1 indicates synergism.

2.3 In vitro detection of apoptosis in A549 cells

The acridine orange-ethidium bromide (AO/EB) staining method was used to investigate induction of apoptosis in A549 cells. The procedure as previously described (Ribble et al., 2005) involved seeding of A549 cells (104 cells/well) in a 96-well plate followed by a 24-hr recovery at 37°C. Treatment consisted of DMSO, C-DIM-5 (10 μM, 20 μM), C-DIM-8 (10 uM, 20 μM), doc (10 nM), C-DIM-5 (10 μM, 20 μM) + doc (5 nM), and C-DIM-8 (10 μM, 20 μM) + doc (5 nM). After 48 hrs cells were washed twice with PBS, permeabilized with 100 μl pre-chilled PBS and stained with 8 ul of staining solution (i.e. ethidium bromide [100 μg/ml] + acridine orange [100 μg/ml] in PBS). The cells were viewed under an Olympus BX40 fluorescence microscope connected to a DP71 camera (Olympus, Japan). Apoptotic cells were quantified and the results presented as means of percentage apoptotic cells ± SD normalized against control.

2.4 In vitro cytotoxicity of aerosolized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8

The in vitro efficacies of the aerosolized C-DIM formulations were evaluated in A549 cells using a six-stage viable impactor connected to the Pari LC Star jet nebulizer and operated for 5 min at a flow rate of 28.3 l/min. A549 cells (106 cells in 15 ml of medium) were seeded in sterile petri dishes (Graseby Andersen, Smyrna, GA) and placed on stage 1 through stage 6 of the viable impactor. A549 cells were exposed to nebulized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 for 2 min. The petri dishes were then incubated at 37°C for 72 hrs under aseptic conditions. Untreated cells were used as a control. Cells were washed with PBS and detached from the petri dish using trypsin. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 g for 5 min and resuspended in media. Cell viability was determined by the trypan blue method (Zhang et al., 2011).

2.5 Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of cell cycle dynamics was carried out as previously described (Li et al., 2012). A549 cells (104 cells/well) suspended in F12K growth media were seeded in a 96-well plate format. Treatment consisted of DMSO, C-DIM-5 (10 μM, 20 μM), or C-DIM-8 (10 μM, 20 μM) and incubation at 37°C for 24 hrs. Cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin and centrifuged for 5 min at 5000 g. Cells were washed in 5 ml of PBS containing 0.1% glucose. Cells were then resuspended in 200 μl of PBS, followed by permeabilization and fixation by drop wise addition of 5 ml pre-chilled ethanol (70%) and kept at 4°C for 1 hr. Cells were pelleted and washed with 10 ml PBS. The cell suspension was incubated in 300 μl staining solution comprising of 1 mg/ml propidium iodide (PI) and 10 mg/ml RNAse A (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 hr and analyzed by FACS using the BD FACSCALIBUR.

2.6 Caco2 permeability assays

Caco2 cells were grown in DMEM media fortified with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, 10 mM HEPES, and a penicillin/streptomycin/neomycin cocktail in 75 cc flasks. Cells were maintained under conditions of 5% CO2 and 95% humidity at 37°C. Sub-cofluent Caco2 monolayers were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffred saline (DPBS) 2x and detached with trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) and seeded (5.0×104) in a 0.5 ml-volume into the apical chamber (with 1.5 ml of cell-free media in the basolateral chamber) of a Costar® collagen-coated PTFE membrane transwell assembly (Corning, Lowell, MA). Caco2 cells were maintained by media replacement in both chambers every other day for 14 days, and subsequently, daily for up to 21 days. The integrity of the monolayer formed was assessed by trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) readings employing a Millicell (MilliPore, Bedford, MA). Monolayers registering net TEER values ranging between 400 – 500 Ω were used for permeation assay. Before the permeation study, Caco2 monolayer integrity and permeability were assessed using the Millicell and Lucifer yellow respectively. Permeation was carried out with 10 μg/ml (0.5 ml) of C-DIM-5 or C-DIM-8 (in pH-adjusted HBSS-HEPES buffer) and 1.5 ml of blank HBSS-HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) added to the apical and basolateral compartments respectively. The transwells were perfused with 5 % CO2 in a humidified 37°C atmosphere under constant stirring at 50 rpm. Collection of permeated samples (200 μl) from the basolateral compartments were done at 2 hr. The samples were injected into a Symmetry C18 column of an HPLC under an isocratic flow of 1 ml/min in an acetonitrile:water (70:30) mobile phase and detection done at a wavelength of 240 nm. Apparent permeability (Papp) was computed thus:

2.7 Formulation and aerodynamic characterization of nebulizer solution

Aqueous formulations suitable for nebulization were prepared by dissolving C-DIM-5 (50 mg) in 0.5 ml ethanol and 500 mg of vitamin E TPGS and diluting up to 10 ml with distilled water to obtain a 5 mg/ml solution of C-DIM-5. This was used for in vitro cytotoxicity studies and aerodynamic characterization. A 5 mg/ml nebulizing solution was prepared and used for animal studies and comparable formulations of C-DIM-8 were also prepared. An eight-stage Anderson cascade impactor (ACI), Mark II was used for particle size assessment. Impactor plates were coated with 10% pluronic-ethanolic solution to mitigate particle rebound. The formulation was nebulized using a PARI LC STAR jet nebulizer at a dry compressed air flow rate of 4 l/min for 5 min into the cascade impactor at a flow rate of 28.3 l/min. Aerosol particles deposited along the ACI (throat, jet stage, plates on impactor stages 0–7, and filter) were collected by washing with 5 ml of mobile phase comprising acetonitrile:water (70:30) and analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The analysis was performed on a Waters HPLC system using a Symmetry C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) with a Nova-Pack C8 guard column at a wavelength of 240 nm and flow rate of 1 ml/min. The mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) and geometric standard deviation (GSD) were computed from the obtained impactor data utilizing a validated protocol (Patlolla et al., 2010). Aerodynamic analyses of the samples were determined in triplicate and data presented as means with SD.

2.8 In vivo metastatic lung tumor model

All experiments involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) of Florida A & M University. Female Nu/Nu mice weighing 20–25 g (Charles River Laboratories) were utilized for determining anticancer activities. The animals were acclimated to laboratory conditions for one week prior to experiments and were maintained on standard animal chow and water ad libitum. The room temperature was maintained at 22±1°C and the relative humidity of the experimentation room was kept in the range of 35–50%. For nebulization studies, four days prior to the start of experiment, animals were trained using nebulized water for 30 min to acclimatize them to the nebulizing environment and prevent any discomfort during the administration of the drug formulations. To induce tumor growth in the lungs, single cell suspensions of A549 cells were harvested from subconfluent cell monolayers. These were suspended in a final volume of 100 μl PBS and inoculated into female athymic nude mice (2 × 106 cells per mouse) by tail vein injection to induce pulmonary metastasis. The animals were randomized into six (6) groups 24 hrs post injection and kept for 14 days before tumor growth in lungs. The metastatic tumor model was validated previously for consistency in tumor induction and incidence using 1 × 106 (group 1), 2 × 106 (group 2), and 3 × 106 (group 3) cells per mouse (n=6). The protocol for group 2 was adopted for the study since it satisfied the requirements of tumor induction and survival of animals within the experimental period of 6 weeks. The tumor incidence was consistent across all animals with statistically insignificant variability in tumor volume, weight and nodule (p<0.05).

2.9 Pulmonary delivery of aerosolized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8

Mice were held in SoftRestraint™ (SCIREQ Scientific Respiratory Equipment Inc, Montreal, QC) attached to an inExpose™ (SCIREQ) nose-only inhalation tower and exposed to the aerosolized drug for 30 min. Treatment consisted of 8 animals in each group which were (i) control group (nebulized vehicle), (ii) Group II (5 mg/ml of nebulized C-DIM-5), (iii) Group III (5 mg/ml of nebulized C-DIM-8), (iv) Group IV (5 mg/ml of nebulized C-DIM-5 + 10 mg/kg/day of doc i.v.), (v) Group V (5 mg/ml of nebulized C-DIM-8 + 10 mg/kg/day of doc i.v.), and (vi) Group VI (10 mg/kg/day of doc i.v. 2x/week). Treatment was continued for 4 weeks on alternate days and weights were recorded 2x/week. On day 42, all animals were euthanized by exposure to isoflurane. Mice were then dissected and lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen were removed and washed in sterile PBS. Lung weights, tumor weights and volume were estimated. Organs were removed, and either fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Histologic sections were made from lung tissues and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for further analysis. Where applicable, doc indicates treatment of mice by intravenous (i.v.) injection of docetaxel by tail vein injection 2x/week, C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 indicate 30 min exposure of mice to 5 mg/ml nebulization on alternate days respectively. C-DIM-5 + doc and C-DIM-8 + doc indicate 30 min exposure of mice to 5 mg/ml nebulized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 on alternate days respectively plus intravenous injection of doc 2x/week.

2.10 Total Deposited Dose

The estimated total deposited amount of inhaled drug (D) for the ambient air was calculated by the following formula:

Where, CC-DIM = concentration of C-DIM in aerosol volume (C-DIM-5; 48.9 μg/l, C-DIM-8; 51.6 μg/l) estimated as the amount of C-DIM received from each port of the inhalation assembly. V = volume of air inspired by the animal during 1 min (1.0 l min/kg); DI = estimated deposition index (0.3 for mice), and T = duration of treatment in min (30 min). Under these conditions, the total deposited dose of aerosol formulations of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 were 0.440 mg/kg/day and 0.464 mg/kg/day respectively.

2.11 Western blot analysis

Tissue homogenates from excised lung tumor were lysed on ice using RIPA buffer (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO). Total protein content was determined by the BCA method of protein estimation according to manufacturer’s protocol. The protein samples (50 μg) were separated on a Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA) and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes as previously described (Ichite et al., 2010). The blots were then probed with primary antibodies targeting cleaved caspase8, cleaved caspase3, PARP, cleaved PARP, survivin, NfkB, p21, Bcl2, TR3 and β-actin (as loading control). Following incubation of membranes with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, chemiluminescent signal detection of proteins of interest was aided by autoradiography following exposure to SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Rockford, IL). Blots were quantified by densitometry with the aid of ImageJ (rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) and the results presented as means of protein/β-actin ratio with SD.

2.12 Mouse Cancer PathwayFinder PCR array

Total RNA from lung tissue homogenate was extracted using Trizol reagent per manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA) and converted to complementary DNA using SABiosciences’ RT2 First Strand Kit. The gene expression of a panel of 84 genes representing six biological pathways implicated in transformation and tumorigenesis was profiled using the Mouse Cancer PathwayFinder RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array. The array included five controls including GAPDH and β-actin as housekeeping genes. Amplification was performed on an ABI 7300 RT-PCR and data analysis done with a PCR Array Data Analysis Software (SA Biosciences, Valencia CA).

2.13 Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase-Mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay

Apoptosis detection on paraffin-embedded the lung sections was carried out using the DeadEnd TM Colorimetric Apoptosis Detection System (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Micrographs of the stained sections (x 40) were obtained with the aid of an Olympus BX40 fluorescence microscope connected to a DP71 camera (Olympus, Japan) with a DP controller and DP manager software. Quantification of apoptotic cells was done using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda MD).

2.14 Immunohistochemistry for VEGF and TR3 expression

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung sections mounted on slides were deparaffinized with xylene and dehydrated through graded concentrations of alcohol, and then incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxidase for 20 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Following antigen retrieval for VEGF, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody for VEGF consequent to incubation with biotinylated secondary antibody, followed by streptavidin. Following addition of substrate-chromogen and counterstaining with hematoxylin, VEGF expression were identified by the brown cytoplasmic staining. Immunostaining for TR3 was carried out following the same protocol using primary antibody for TR3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz CA). Established (VEGF or TR3) immunoreactive lung tissue sections and primary antibody-null sections were included as positive and negative controls respectively. Areas showing immunoreactivity for VEGF or TR3 coupled with evidence of tissue remodeling as evidence of tumor growth were selected; and five random fields (under a combined magnification of x400) were selected for scoring. Scoring of VEGF or TR3 immunopositivity was carried out by calculating the immunohistochemical score (IHS) as the sum of the quantity and staining intensity scores as demonstrated by Saponaro et al. (Saponaro et al., 2013). Here, the quantity score (percentage immunopositive cells; 0=immunonegative, 1=25% immunopositive cells, 2=26–50% immunopositive cells, 3=51–75% immunopositive cells, and 4=76–100% immunopositive cells) and staining intensity score (0=no intensity, 1=weak intensity, 2=moderate intensity, and 3=strong intensity) were combine to give a minimum-to-maximum IHS of 0–7. Scoring was done by two researchers independently at three different times and the data collated and the mean IHS computed. Staining for each marker was done in triplicates and the experiments were repeated three times.

2.15 Assessment of Microvessel Density

Tissue sections (4–5 μm thick) mounted on poly-L-lysine–coated slide were deparaffinized and blocked for peroxidase activity. After washing with PBS, the sections were pretreated in citrate buffer in a microwave oven for 20 min at 92–98°C. After washing (2x) with PBS, specimens were incubated in 10% normal goat serum for 20 min. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with a 1:500 diluted mouse CD31 monoclonal antibody at room temperature for 1 hr, followed by a 30 min treatment with rabbit anti-mouse antibody. After washing (3x) with PBS, the section was developed with diaminobenzidene-hydrogen peroxidase substrate, and counterstained with hematoxylin. To calculate microvessel density (MVD), three most vascularised areas of the tumor (‘hot spots’) were selected and mean values obtained by counting vessels. A single microvessel was defined as a discrete cluster of cells positive for CD31 staining, with no requirement for the presence of a lumen. Microvessel counts were performed at x400 (x40 objective lens and x10 ocular lens; 0.74 mm2 per field). Tumors with <200 microvessels/mm−2 were assigned a low microvessel density, whereas those with >200 microvessels/mm−2 were assigned a high microvessel density (Couvelard et al., 2005).

2.16 Statistics

One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s and Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Tests were performed to determine the significance of differences between control and all treatment groups and among groups respectively using GraphPad PRISM version 5.0. Differences were considered significant in all experiments at p<0.05 (*, significantly different from untreated controls; **, significantly different from C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 and doc single treatments unless otherwise stated).

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 inhibit growth of A549 cells

C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 were significantly cytotoxic (p<0.05) to A549 cells with 24 hr IC50 values of 14.29±2.30 μM and 16.18±1.59 μM respectively (Fig. 1A and 1B). The broad spectrum of cytotoxic activities of the C-DIM compounds was also evident in LnCap, PC3, and H460 cell lines (Fig. 1C and 1D). Interaction of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 with doc inhibited A549 cell growth exponentially with CI values of 0.46 ± 0.027 and 0.51 ± 0.031 (i.e. synergistic) respectively. Deposition on stages 3, 4, 5 and 6 were selected, representative of the respirable mass and used in the assessment of cytotoxicity (Fig. 1E and 1F). Cell survival on stage 5 of the viable impactor significantly decreased to 17.75% and 17.10% (p < 0.05) after treatment with nebulized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 respectively.

Figure 1.

C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 alone and in combination with docetaxel (doc) inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in NSCLC. (A, B, C, D) A549, LnCap, PC3, and H460 cells were treated with C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 or DMSO for 24 and cell viability was determined by crystal violet staining. The experiment was repeated three times with three replicates per treatment group and the data are presented as means with SD (n = 3 per group). *P<0.05 versus control and **P<0.05 versus C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 and doc single treatments. (E, F) Cytotoxicity of nebulized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 in A549 cells. Cells (1×106) were seeded in sterile petri plates in 15 ml of F12k media, exposed to aerosolized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 for 2 min and viability determined by the trypan blue exclusion as described in materials and methods. Results are presented as percentage cell viability of treatment normalized against the control treatment (nebulizer solution). Experiments were done in triplicates and repeated 3 times.

3.2 C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 induce apoptosis and cause Go/G1-phase to S-phase arrest in A549 cells

Representative fluorescence micrographs of acridine orange-ethidium bromide-stained cells revealed the percentages of cells undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 2A). This was after treatment with DMSO, doc (10 nM), C-DIM-5 (10 μM), C-DIM-5 (10 μM) + doc (5 nM), C-DIM-8 (10 μM), C-DIM-8 (10 μM) + doc (5 nM), C-DIM-5 (20 μM), C-DIM-5 (20 μM) + doc (5 nM), C-DIM-8 (20 μM), and C-DIM-8 (20 μM) + doc (5 nM) (Fig. 2A). There was evidence of induction of early and late apoptosis by doc (10 nM) [11.5±1.00%], C-DIM-5 (10 μM) [20.5±1.85%], and C-DIM-8 (10 μM) [26±1.05%] (Fig. 2B). This was augmented when C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 where combined with doc [C-DIM-5 (10 μM) + doc (5 nM), 30±2.90%; C-DIM-8 (10 μM) + doc (5 nM), 34±3.60%] (Fig. 2B). The number of apoptotic cells significantly increased (p<0.05) at higher concentrations (20 μM) of C-DIM-5 [24±1.80%] and C-DIM-8 [25.5±2.40%]. This was further enhanced when 20 μM C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 were co-treated with 5 nM doc [40±3.45%, and 41±3.60% respectively] (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

(A, B) Induction of apoptosis by C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8, doc and their combinations. Cells were treated with (i, ii) DMSO, (iii, iv) doc (10 nM), (v, vi) C-DIM-5 (10 μM), (vii, viii) C-DIM-8 (10 μM), (ix, x) C-DIM-5 (10 μM) + doc (5 nM), (xi, xii) C-DIM-8 (10 μM) + doc (5 nM), (xiii, xiv) C-DIM-5 (20 μM), (xv, xvi) C-DIM-8 (20 μM), (xvii, xviii) C-DIM-5 (20 μM) + doc (5 nM), and (xix, xx) C-DIM-8 (20 μM) + doc 5 nM, incubated at 37 °C for 24 hrs and apoptosis was determined by acridine orange-ethidium bromide staining as described in materials and method. Experiments were done in triplicates and repeated 3 times. *P<0.05 versus control and **P<0.05 versus C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 and doc single treatments. (C) C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 cause cell cycle arrest. Cells were treated with DMSO, C-DIM-5 (10μM), C-DIM-8 (10μM), C-DIM-5 (20μM) and C-DIM-8 (20μM) respectively, then harvested, fixed, stained and analyzed by FACS as described in materials and methods. Data are presented as means of events with SD of 3 experiments (*P<0.05 vs DMSO).

Treatment of A549 cells with DMSO resulted in accumulation of 72.34±0.51% of cells in G1, 3.20±0.13% in G2 and 24.58±0.49% of cells in S-phase (Fig. 2C). However, after treatment with 10 μM C-DIM-5, 76.98±0.51% of cells accumulated in G1, 1.20±0.21% in G2 and 21.82±0.52% in S-phase. Treatment with C-DIM-5 (20 μM) increased cells accumulating in G1 to 82.46±0.95%, 2.25±0.31% in G2 and decreased cells in S-phase 15.29±0.64% (Fig. 2C). Treatment of A549 cells with 10 μM C-DIM-8 resulted in 74.46±0.66%, 2.15±0.35%, and 23.39±0.75% of cells accumulating in G1, G2, and in S-phase respectively, whereas at 20 μM, C-DIM-8 arrested 81.66±0.22% cells in G1, 2.21±0.44% in G2, and 16.13±0.29% in S-phase (Fig. 2C).

3.3 Caco2 permeability assays

The apparent permeability (Papp) of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 under acidic conditions (pH 5.0 and pH 6.0) was investigated as a basis for their oral delivery (Fig. 3). At pH of 5.0 and 6.0 the Papp of C-DIM-5 was 1.12×10−7 cm/s and 1.11×10−7 cm/s respectively (Fig. 3A). The Papp of C-DIM-8 increased from 1.0712×10−7 cm/s at pH 5.0 to 1.11×10−7 cm/s at pH 6.0. (Fig. 3B) While there was no difference between the two Papp of C-DIM-5, the differences in the Papp of C-DIM-8 were not considered significant (p>0.05). The Papp of C-DIM-5 did not change significantly at either pH of 7.0 or 8.0 (Fig. 3A) while that of C-DIM-8 increased significantly (p<0.05) to 1.15×10−7 cm/s and 1.16×10−7 cm/s respectively compared to Papp at pH of 5.0 and 6.0 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

In vitro permeability of (A) C-DIM-5 and (B) C-DIM-8 across Caco2 monolayer. Cells were maintained on collagen-coated transwells for 21 days and permeation studies performed as described under materials and methods. Both compounds show poor permeabilities under acidic and alkaline conditions with C-DIM-8 exhibiting a pH–dependent increase at high pH. Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism and represented as the means with SD of 3 experiments. Significant differences (*P<0.05 vs acidic pH) are indicated.

3.4 Aerodynamic characterization of nebulized C-DIMs

Assessment of size and shape characteristics of nebulized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 formulations was done by determining their mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) and geometric standard deviation (GSD) using ACI as depicted in material and methods. As shown for nebulized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 (Figures 4A and 4B respectively), significant deposition of aerosol droplets were achieved on stages 4 through 6 of the impactor. C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 formulations yielded particles with aerodynamic capabilities for deep pulmonary deposition with MMAD of 1.92 ± 0.22 um, GSD of 2.31 ± 0.12 and a MMAD of 1.84 ± 0.31 um and GSD of 2.11 ± 0.15) respectively.

Figure 4.

In vitro characterization of aerosolized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 emulsified with D-α-Tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS). (A, B) Aerosol droplet size distribution. C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 were emulsified with TPGS (5 mg/ml) and nebulized for 5 min and the concentration of C-DIM determined by HPLC as described in materials and methods. Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism and represented as the means with SD of 3 experiments. Significant (*P<0.05 vs unnebulized formulation) differences are indicated.

3.5 C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 and Docetaxel combinations inhibit lung tumor growth

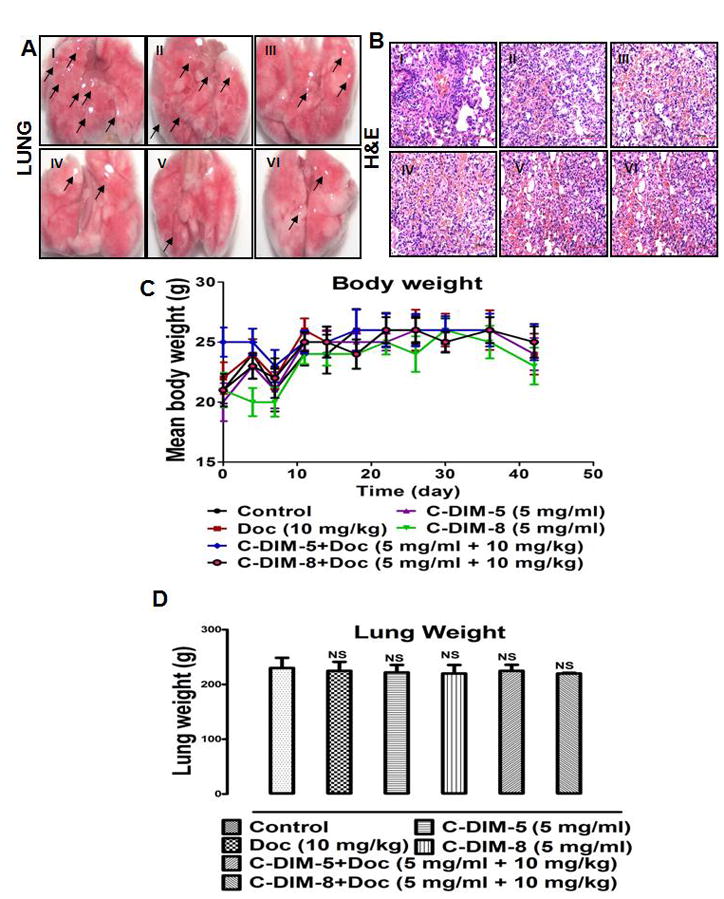

Representative lungs (Fig. 5A) with tumor nodules (black arrows) are shown for mice treated with nebulizer vehicle as control, nebulized C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 and their combinations with doc. Compared to control lungs (12 nodules, Fig. 5A-I), tumor nodules were decreased after treatment with doc (7 nodules, Fig. 5A-II), C-DIM-5 (5 nodules, Fig. 5A-III), C-DIM-8 (3 nodules, Fig. 5A-IV), C-DIM-5 + doc (2 nodules, Fig. 5A-V) and C-DIM-8 + doc (2 nodules, Fig. 5A-VI). Reduction in tumor nodules in all treatment groups were considered significant compared to control (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Regression analysis of lung tumor. Mice were randomized into 6 groups (n = 8 per group) and treated for 4 weeks with (i) vehicle, (ii) doc (10 mg/kg/day), (iii) C-DIM-5 aerosol (30 min exposure of 5 mg/ml), (iv) C-DIM-8 aerosol (30 min exposure of 5 mg/ml), (v) C-DIM-5 aerosol (30 min exposure of 5 mg/ml) + i.v. doc (10 mg/kg/day), (vi) C-DIM-8 aerosol (30 min exposure of 5 mg/ml) + i.v. doc (10 mg/kg/day). (A) Lung tumor morphology was determined as described in the material and methods. (B) Body weights were recorded 2x a week and results were presented as means of body weight with SD (n = 8 per group). (C) Lung pathology was investigated by H&E staining as described under materials and methods. (D) Mice lung were weighed following resection to determine changes due to toxicity or pathology. Data were presented as means with SD (n = 8 per group). The differences in lung weight were not determined to be significant (NS = not significant).

H&E staining of representative lung sections (Fig. 5B) also showed similar behavior. Evidence of tissue remodeling and migration are evidenced in control (Fig. 5B-I) by abundant nuclei foci. However, less pathology is evident in groups treated with doc (Fig. 5B-II), C-DIM-5 (Fig. 5B-III), C-DIM-8 (Fig. 5B-IV), and more so in C-DIM-5 (Fig. 5B-V) C-DIM-8 (Fig. 5B-VI) combinations with doc.

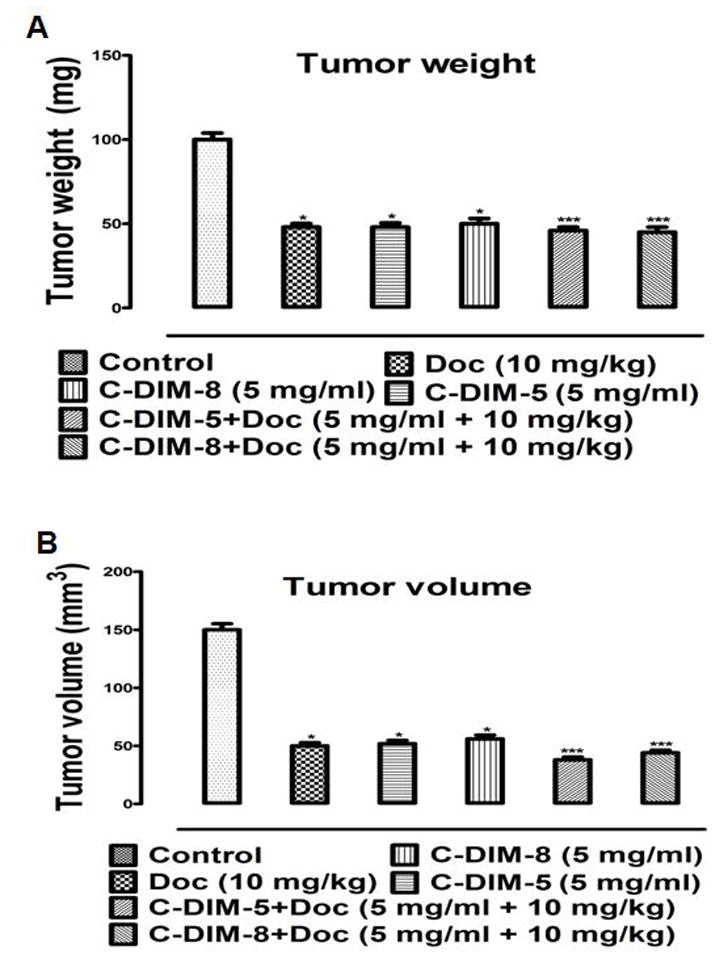

There were no variations in body weight (Fig. 5C) or lung (Fig. 5D) across all treatment groups compared to the control mice. There were significant differences (p < 0.05) in the tumor weights from mice treated with doc (48±3.68 mg), C-DIM-5 (48±4.20 mg), C-DIM-8 (50±5.36 mg), C-DIM-5 + doc (46±3.47 mg) and C-DIM-8 + doc (45±5.20 mg) compared to vehicle (100±6.84 mg) (Fig. 6A). Decreased tumor growth based on volumes was also significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in the treated compared to control mice (Fig. 6B). A relative mean tumor volume of 150±8.90 mm3 was observed in the control mice, and tumor volume decreased following treatment with doc (66.67%; 50±4.77 mm3), C-DIM-5 (65.33%; 52±4.80 mm3), C-DIM-8 (62.67%; 56±5.80 mm3), C-DIM-5 + doc (74.67%; 38±4.20 mm3), and C-DIM-8 + doc (70.67%; 44±3.80 mm3) (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Tumor regression analysis. (A) Mean tumor weights and (B) volumes were determined as described in the materials and methods. Tumor volumes were calculated using the formula Volume = ((width)2 × (length)) × 0.5. Results are presented as means of tumor volume with SD (n = 8 per group). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare differences observed between control and treatment groups and Turkey’s test was used to compare differences between combination and single treatment groups. Significant (*P<0.05 vs control and **P<0.05 vs C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 and doc single treatments) differences are indicated.

3.6 C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 inhibit VEGF expression in lung tumors

C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 nebulized formulations inhibited VEGF expression in A549 lung tumor when given alone and when combined with doc (Figure 7A). This was observed as positive (dark brown) immunohistochemical staining for VEGF on lung sections. Quantification of VEGF-positive cells was represented as percentage of the mean normalized against control (Figure 7B). The results showed a decrease in VEGF staining following treatment with doc (68±5.82%; Fig. 7A-II), C-DIM-5 (49±5.30%; Fig. 7A-III), C-DIM-8 (54±5.83%; Fig. 7A-IV), C-DIM-5 + doc (26±4.25%; Fig. 7A-V) and C-DIM-8 + doc (28±4.02%; Fig. 7A-VI) compared to control (Fig. 7A-I). The decrease in VEGF expression was significant across all treatment groups relative to control and between the single and combination treatments of the same compounds (p < 0.05). However, the differences in VEGF expression between C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 and between their combinations were not significant (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Histology of lung sections from metastatic lung tumors. Mice from the various treatment groups (see Fig. 5) were stained and quantitated for (A, B) VEGF, (C, D) CD31 as described in materials and methods. Results are presented as percentage VEGF-positive cells (B) and average microvessel density (D) of control (set at 100 %). Results are replicate treatments for each group (n = 3 per group) and presented as means ± SD. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare differences observed between control and treatment groups and Turkey’s test was used to compare differences between combination and single treatment groups. Significant (*p<0.05 vs control and **p<0.05 vs C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 and doc single treatments) differences are indicated.

3.7 C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 decrease microvessel density in lung tumors

Microvessel density (MVD) was determined by immunopositive staining for CD31 (Fig. 7C). Tissue sections stained dark brown for CD31 with a progressive decrease in staining observed for sections from the treatment groups compared to the control. MVD assessment of sections showed significant reduction (p < 0.05) in MVD in the groups treated with doc (182±10.28 microvessels/mm2; Fig. 7C-II and Fig. 7D), C-DIM-5 (164±15.31 microvessels/mm2; Fig. 7 C-III and Fig. 7D), C-DIM-8 (158±10.85 microvessels/mm2; Fig. 7 C-IV and Fig. 7D), C-DIM-5 + doc (106±9.50 microvessels/mm2; Fig. 7 C-V and Fig. 7D), and C-DIM-8 + doc (118±11.07 microvessels/mm2; Fig. 7 C-VI and Fig. 7D) compared to 248±25.11 microvessels/mm2 in the control (Fig. 7 C-I and Fig. 7D).

3.8 C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 induce apoptosis in lung tumors

Treatment-related induction of apoptosis was determined by TUNEL staining which showed positive staining for DNA fragmentation as dark-brown or reddish staining (Figure 8A). Compared to the untreated control group (Figure 8B), there was significantly increased (p<0.05) DNA fragmentation in mice treated with doc (38±4.02%), C-DIM-5 (56±6.20%) and C-DIM-8 (60±5.40%), combination treatment of C-DIM-5+doc (78±8.11%) and C-DIM-8 +doc (80±8.90%).

Figure 8.

Histology of lung sections from metastatic lung tumors. (A) TdT-mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling was performed on tumor sections from mice from the various treatment groups (see Fig. 5). (B) Staining were quantitated and presented as percentage of apoptotic cells normalized against control. (C) Immunohistochemical staining for TR3 expression following treatment as above were scored and presented as means of IHC score (D). Results are replicate treatments for each group (n = 3 per group) and presented as means ± SD One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare differences observed between control and treatment groups and Turkey’s test was used to compare differences between combination and single treatment groups. Significant (*p<0.05 vs control) differences are indicated.

3.9 C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 and TR3 expression in lung sections

Positive staining for TR3 was evident as dark-brown staining (Fig. 8C). The pattern of TR3 expression following immunostaining was similar in intensity and was evident of nuclear localization in all groups. TR3 immunopositivity was high and comparable among all groups (IHS=5–6) and the differences observed were considered to be statiscally insignificant (p<0.05) (Fig. 8D).

3.10 C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 inhibit genes involved in tumor initiation and metastasis

A PCR array containing 84 genes that are involved in various aspects of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis was used to analyze tumor samples from the various treatment groups (Fig. 9A and 9B). Both C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 decreased expression of Bcl2, Ccne1, EGFR, Met, MMP2, MMP9, Myc, NCAM1, PTEN, VEGF A, VEGF B, and VEGF C mRNAs (Figure 9A and 9B). C-DIM-5 also downregulated expression of ANGPT1, Ccd25a and Birc5 mRNAs (Figure 9A), and C-DIM-8 inhibited the levels of ATM (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9.

PCR Array of modulators of tumor growth, tumor inhibition, apoptosis, metastasis, and angiogenesis. (A, B) Gene expression profile of resected metastatic lung tumor. RNA from the various treatment groups (see Fig. 5) was converted to cDNA and analyzed using a Mouse Cancer PathwayFinder RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array as outlined in the materials and methods. Results are expressed as means ± SD Significant (*P<0.05 vs untreated controls) differences are indicated. Results are expressed as means ± SD for at least 3 replicate determination for each treatment group and expressed as percentage of values in control tumors (set at 100 %). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare differences observed between control and treatment groups and Turkey’s test was used to compare differences between combination and single treatment groups. Significant differences (*P<0.05 vs control) are indicated.

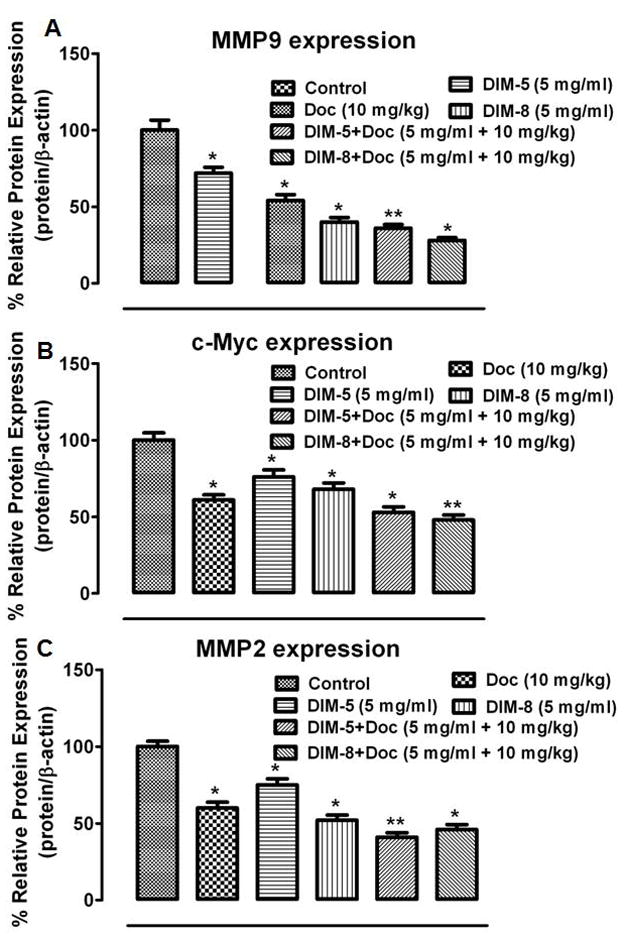

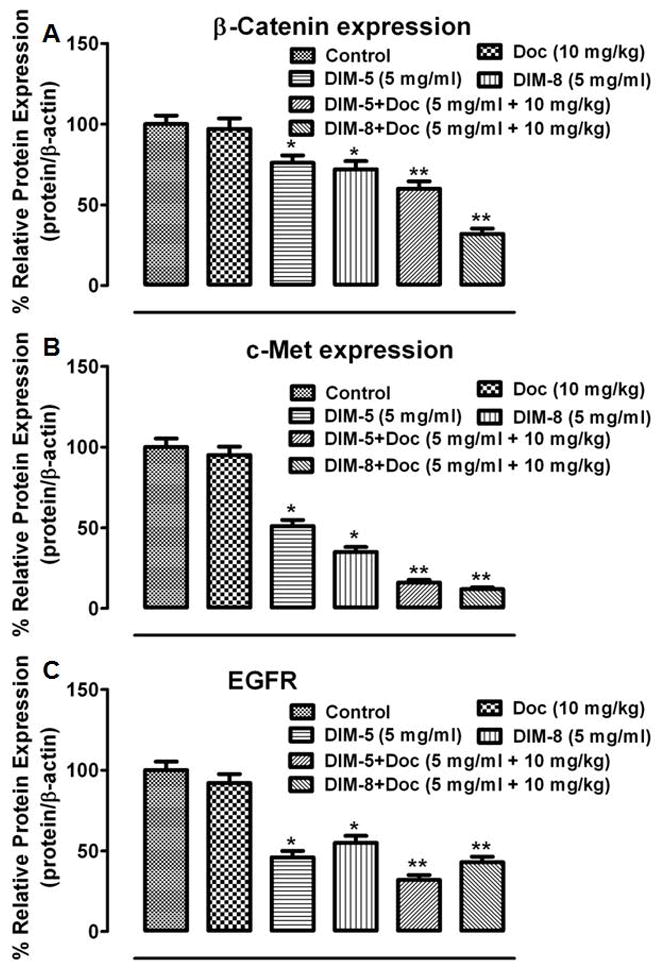

Both C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 increased markers of apoptosis including cleaved PARP while uniquely increasing the expression of cleaved Caspase8 and cleaved Caspase3 respectively (Fig. 10A and 10B). C-DIM-5 also induced the expression of p21, the transcriptional modulator of the tumor suppressor p53 (Fig. 10A). Differentially, nebulized C-DIM-8 alone significantly inhibited the expression of PARP, Bcl2, and Survivin compared to the control and nebulized C-DIM-5 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 10B). Whilst both C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 and their combinations with doc decreased the expression of β-catenin, MMP9, MMP2, c-Myc, c-Met and EGFR which were significant compared to control (Fig. 10C and 10D), there were significant differences between them (Fig. 11 and 12). C-DIM-8+doc significantly decreased the expression MMP9, c-Myc, β-catenin compared to C-DIM-5+doc (p<0.05) (Fig. 11A, 11B, 12A respectively). C-DIM-5+doc and C-DIM-8+doc inhibited EGFR expression significantly but the differences between them were not significant (Fig. 12C).

Figure 10.

Western blot studies of modulators of tumor growth, tumor inhibition, apoptosis, metastasis, and angiogenesis. (A) C-DIM-5 and (B) C-DIM-8 modulate gene products associated with growth, survival and (C, D) metastasis. Tumor lysates from the various treatment groups were analyzed by Western blot as outlined in the materials and method.

Figure 11.

Lung tumor lysates from the various treatment groups (see Fig. 10) were analyzed by Western blot for (A) MMP9, (B) c-Myc, (C) MMP-2 and their expression estimated using the ImageJ software (imagej.nih.gov/ij/download/). Protein expression of targets were normalized against β-actin for at least 3 replicate determination for each treatment group and the results expressed as percentage of control lysate (set at 100 %). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare differences observed between control and treatment groups and Turkey’s test was used to compare differences between combination and single treatment groups. Significant differences (*P<0.05 vs control and **P<0.05 vs C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 and doc single treatments) are indicated.

Figure 12.

Lung tumor lysates from the various treatment groups (see Fig. 10) were analyzed by Western blot for (A) β-catenin, (B) c-Met, (C) EGFR and their expression estimated using the ImageJ software (imagej.nih.gov/ij/download/). Protein expression of targets were normalized against β-actin for at least 3 replicate determination for each treatment group and the results expressed as percentage of control lysate (set at 100 %). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare differences observed between control and treatment groups and Turkey’s test was used to compare differences between combination and single treatment groups. Significant differences (*P<0.05 vs control and **P<0.05 vs C-DIM-5, C-DIM-8 and doc single treatments) are indicated.

4.0 DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the enhanced anti-metastatic and anticancer activities of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 formulated for inhalation delivery. C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 act on TR3 as activator and deactivator respectively (Cho et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2011a). They are highly lipophilic with nominally low membrane permeability. These properties preclude the achievement of optimal concentrations at the tumor microenvironment when administered orally. And while the anticancer activities of various C-DIM analogs have been studied, their abilities to inhibit metastasis haven’t engendered much interest (Chintharlapalli et al., 2005; Cho et al., 2010, 2008, 2007). Therefore, we planned to overcome the barriers to effective therapy in advanced lung cancer by formulating C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 in inhalable forms for local lung delivery in a metastatic tumor model.

C-DIM-8 and C-DIM-5 are generally non-toxic in normal tissue at therapeutic concentrations (Chintharlapalli et al., 2005; Cho et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2010, 2009). However, both compounds inhibited A549 cell growth when administered alone and acted in synergism with doc.

The nuclear staining properties of acridine orange and ethidium bromide were employed in in vitro detection of apoptosis in A549 cells (Ribble et al., 2005). Herein, we recognize the cytotoxic activities of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 in their induction of early and late apoptosis in a concentration dependent manner. Together with a concentration-dependent G0/G1 arrest of A549 cells, C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 showed remarkable cytotoxic profiles. These results were paralleled by inhibition of antiapoptotic survivin mRNA and protein expression in tumors from mice treated with C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 and was similar to observations reported by Lee et al. (Lee et al., 2009) in pancreatic cells. Consistent with FACS analysis, C-DIM-5 also induced the expression of the tumor suppressor protein p21, an inhibitor of cell cycle progression (Lee et al., 2009).

Pre-formulation studies on the aqueous solubility and intestinal permeability of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 revealed that these compounds were highly insoluble with low permeability. Thus, to ensure optimal concentration at the tumor microenvironment, the inhalation route was exploited; our previous studies with a PPARγ-active C-DIM demonstrated the efficacy of the inhalation method for effective delivery (Ichite et al., 2009). To ensure efficient deposition in the lung for effective therapeutic effect, particles of aerosolized droplets with an effective cutoff diameter of about 4 μm with an optimal range of 1–3 μm (Patlolla et al., 2010) corresponding to particles collected on stage 5 of the viable impactor are preferred. Hence, cytotoxicity studies of aerosol droplets collected on this stage were used to predict effectiveness for in vivo lung alveolar deposition; with both formulations registering appreciable cytotoxic activities. We also characterized the aerodynamic behavior of the aerosol particles using the eight-stage ACI by estimating the MMAD and GSD with acceptable respirabilities of aerosolized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 being attained.

The metastatic mouse tumor model closely recapitulates the advanced stages of tumor development (Boffa et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2011b) and was chosen to study the anti-metastatic effects of aerosolized C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8. Physical examination of resected lungs showed different lung morphologies with significant tumor nodule reduction in the treatment groups compared to control. Histological staining (H&E) of lung sections displayed highly disseminated cytoplasmic structures with less occurrence of nuclear matter in the treatment groups compared to the control. Absence of toxicity of treatment was supported by no change in body or lung weight measurements over the treatment period. However, significant tumor regression was observed following treatment with doc, C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 alone, and more pronounced effects were observed for the combination of C-DIMs plus doc. Importantly, the 0.440 mg/kg and 0.464 mg/kg lung deposition doses of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 respectively in nebulized form were 6-fold more than their corresponding oral formulations which gave comparable effects (Lee et al., 2011b). The antimetastatic activities of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 were evident in their inhibition of neovascularization characterized by decreased VEGF and CD31 staining with optimum inhibition occurring in combination treatment with doc which was consistent with TUNEL staining.

Although C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 differentially activate and inactivate TR3-dependent transactivation respectively, both compounds inhibit lung tumor growth, induce apoptosis, and inhibit angiogenesis in vivo and also exhibit comparable effects in vitro. However, these effects were not TR3-dependent as shown from immunostaining and Western blot. Immunostaining for TR3 on lung tumor tissues showed nuclear localization of TR3 and no statistical difference in the IHS score among all groups (Cho et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2011a). The expression of TR3 following treatment with C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 were unchanged compared to control. The similarity in their anticancer activity was also observed in pancreatic cancer (Lee et al., 2010, 2009). Therefore, we further investigated differences between these compounds by investigating genes and selected proteins in treated and control tumors. The pattern of gene and protein expression was similar for C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 with respect to induction or repression of genes associated with growth, survival, and angiogenesis; the only exceptions were in the unique repression of Angpt1, Birc5, and Cdc25a by C-DIM-5 and Atm by C-DIM-8. Previous studies on a series of p-phenylsubstituted C-DIMs including C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 show that all of these compounds induce endoplasmic recticulum (ER) stress (Lei et al., 2008b) and ongoing studies suggest that this response was TR3-dependent via the inactivation pathway. Thus, we concluded that C-DIM-5 may also inactivate TR3 and it is also possible that this compound may be metabolized in vivo to give C-DIM-8 via the oxidative demethylation pathway to yield C-DIM-8.

5.0 CONCLUSION

In summary, our study confirms the efficacy of the C-DIM analogs as potent anticancer agents for treatment of metastatic lung cancer. Our delivery of C-DIM-5 and C-DIM-8 in a metastatic mouse lung tumor by inhalation enhanced multimodal therapeutic effects without causing toxicity and resulted in significant reduction in tumor growth compared to control tumor and a 6-fold efficacy over corresponding oral formulations (Lee et al., 2011a). Both compounds exhibited anti-metastatic, antiangiogenic, and apoptotic activities by influencing the gene and protein expression of various mediators involved in these pathways. These results underpin the usefulness of the C-DIM analogs as candidates for treating advanced stage lung cancer. Current studies are examining the effect of these compounds in overcoming the multi-drug resistant phenotypic properties of cancer stem cells and their mechanisms associated with C-DIM-TR3 interactions are also being investigated.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number 8 G12 MD007582-28 and 2 G12 RR003020.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: Authors would like to disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdelbaqi K, Lack N, Guns ET, Kotha L, Safe S, Sanderson JT. Antiandrogenic and growth inhibitory effects of ring-substituted analogs of 3, 3, ′-diindolylmethane (ring-DIMs) in hormone-responsive LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2011;15;71(13):1401–12. doi: 10.1002/pros.21356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffa DJ, Luan F, Thomas D, Yang H, Sharma VK, Lagman M, Suthanthiran M. Rapamycin inhibits the growth and metastatic progression of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(1 Pt 1):293–300. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Banerjee S, Cui QC, Kong D, Sarkar FH, Dou QP. Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase by 3,3′-Diindolylmethane (DIM) is associated with human prostate cancer cell death in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintharlapalli S, Burghardt R, Papineni S, Ramaiah S, Yoon K, Safe S. Activation of Nur77 by selected 1,1-Bis(3_-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes induces apoptosis through nuclear pathways. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24903–24914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SD, Lee SO, Chintharlapalli S, Abdelrahim M, Khan S, Yoon K, Kamat AM, Safe S. Activation of nerve growth factor-induced B alpha by methylene-substituted diindolylmethanes in bladder cancer cells induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77(3):396–404. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SD, Lei P, Abdelrahim M, Yoon K, Liu S, Guo J, et al. 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-methoxyphenyl)methane activates Nur77-independent proapoptotic responses in colon cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47(4):252–63. doi: 10.1002/mc.20378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SD, Yoon K, Chintharlapalli S, Abdelrahim M, Lei P, Hamilton S, et al. Nur77 agonists induce proapoptotic genes and responses in colon cancer cells through nuclear receptor-dependent and nuclear receptor-independent pathways. Cancer Res. 2007;67(2):674–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Lim do Y, Park JH. Induction of G1 and G2/M cell cycle arrests by the dietary compound3,3′-diindolylmethane in HT-29 human colon cancer cells. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;29;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chougule MB, Patel AR, Jackson T, Singh M. Antitumor activity of Noscapine in combination with Doxorubicin in triple negative breast cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couvelard A, O’Toole D, Turley H, Leek R, Sauvanet A, Degott C, et al. Microvascular density and hypoxia-inducible factor pathway in pancreatic endocrine tumours: negative correlation of microvascular density and VEGF expression with tumour progression. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(1):94–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Chintharlapalli S, Lee SO, Cho SD, Lei P, Papineni S, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent activity of indole ring-substituted 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-biphenyl)methanes in cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66(1):141–50. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1144-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichite N, Chougule M, Patel AR, Jackson T, Safe S, Singh M. Inhalation delivery of a novel diindolylmethane derivative for the treatment of lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(11):3003–14. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichite N, Chougule MB, Jackson T, Fulzele SV, Safe S, Singh M. Enhancement of docetaxel anticancer activity by a novel diindolylmethane compound in human non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15;15(2):543–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolluri SK, Bruey-Sedano N, Cao X, Lin B, Lin F, Han YH, et al. Mitogenic Effect of Orphan Receptor TR3 and Its Regulation by MEKK1 in Lung Cancer Cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003:8651–8667. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8651-8667.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SO, Abdelrahim M, Yoon K, Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Kim K, et al. Inactivation of the orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 inhibits pancreatic cancer cell and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70(17):6824–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SO, Andey T, Jin UH, Kim K, Sachdeva M, Safe S. The nuclear receptor TR3 regulates mTORC1 signaling in lung cancer cells expressing wild-type p53. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SO, Chintharlapalli S, Liu S, Papineni S, Cho SD, Yoon K, et al. p21 expression is induced by activation of nuclear nerve growth factor-induced B alpha (Nur77) in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(7):1169–78. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SO, Li X, Khan S, Safe S. Targeting NR4A1 (TR3) in cancer cells and tumors. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15(2):195–206. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.547481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei P, Abdelrahim M, Cho SD, Liu S, Chintharlapalli S, Safe S. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes inhibit colon cancer cell and tumor growth through activation of c-jun N-terminal kinase. Carcinogenesis. 2008a;29(6):1139–47. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei P, Abdelrahim M, Cho SD, Liu X, Safe S. Structure-dependent activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in pancreatic cancer by 1,1-bis(3′-indoly)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008b;7(10):3363–72. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A, Grafi-Cohen M, Napso T, Azzam N, Fares F. The indolic diet-derivative 3, 3′-diindolylmethane, induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells through upregulation of NDRG1. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012:256178. doi: 10.1155/2012/256178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Shao J, Shen K, Xu Y, Liu J, Qian X. E2F1-dependent pathways are involved in amonafide analogue 7-d-induced DNA damage, G2/M arrest and apoptosis in p53-deficient K562 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jcb.24194.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luszczki JJ, Florek-Łuszczki M. Synergistic interaction of pregabalin with the synthetic cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 mesylate in the hot-plate test in mice: an isobolographic analysis. Pharmacol Rep. 2012;64(3):723–32. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70867-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell MA, Muscat GE. The NR4A subgroup: immediate early response genes with pleiotropic physiological roles. Nucl Recept Signal. 2006;4:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.04002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorrow JP, Murphy EP. Inflammation: a role for NR4A orphan nuclear receptors? Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39(2):688–93. doi: 10.1042/BST0390688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milbrandt J. Nerve growth factor induces a gene homologous to the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Neuron. 1988;1: 183–188. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patlolla RR, Desai PR, Belay K, Singh MS. Translocation of cell penetrating peptide engrafted nanoparticles across skin layers. Biomaterials. 2010;31(21):5598–607. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribble D, Goldstein NB, Norris DA, Shellman YG. A simple technique for quantifying apoptosis in 96-well plates. BMC Biotechnol. 2005;10;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S, Kim K, Li X, Lee SO. NR4A orphan receptors and cancer. Nucl Recept Signal. 2011;9:e002. [Google Scholar]

- Safe S, Papineni S, Chintharlapalli S. Cancer chemotherapy with indole-3-carbinol, bis(3′-indolyl)methane and synthetic analogs. Cancer Lett. 2008;269(2):326–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saponaro C, Malfettone A, Ranieri G, Danza K, Simone G, et al. VEGF, HIF-1a Expression and MVD as an Angiogenic Network in Familial Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey LE, Hagman AM, Williams DE, Ho E, Dashwood RH, Benninghoff AD. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane induces G1 arrest and apoptosis in human acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead CM, Earle KA, Fetter J, Xu S, Hartman T, Chan DC, et al. Exisulind-induced apoptosis in a non-small cell lung cancer orthotopic lung tumor model augments docetaxel treatment and contributes to increased survival. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:479–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittgen BP, Kunst PW, van der Born K, van Wijk AW, Perkins W, Pilkiewicz FG, et al. Phase I study of aerosolized SLIT cisplatin in the treatment of patients with carcinoma of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13: 2414–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HC, Huang CT, Chang DK. Anti-Angiogenic Therapeutic Drugs for Treatment of Human Cancer. J Cancer Mol. 2008;4(2): 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon K, Lee SO, Cho SD, Kim K, Khan S, Safe S. Activation of nuclear TR3 (NR4A1) by a diindolylmethane analog induces apoptosis and proapoptotic genes in pancreatic cancer cells and tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(6):836–42. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZG, Li XB, Gao L, Liu GW, Kong T, Li YF, et al. An updated method for the isolation and culture of primary calf hepatocytes. Vet J. 2011;191(3):323–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]