To the Editor

The sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway plays an essential role during human development, and its dysregulation causes developmental defects such as holoprosencephaly and a variety of human cancers, including basal-cell carcinomas.1 Although mutations in patched homologue 1 (PTCH1) and smoothened homologue (SMO) encoding the receptors PTCH1 and SMO, respectively, are known to predispose to inherited and sporadic basal-cell carcinomas, up-regulation of hedgehog ligands such as sonic hedgehog have been associated with lethal tumors such as pancreatic or lung cancer. Here, we describe a person with overexpression of SHH and widespread and aggressive basal-cell carcinomas.

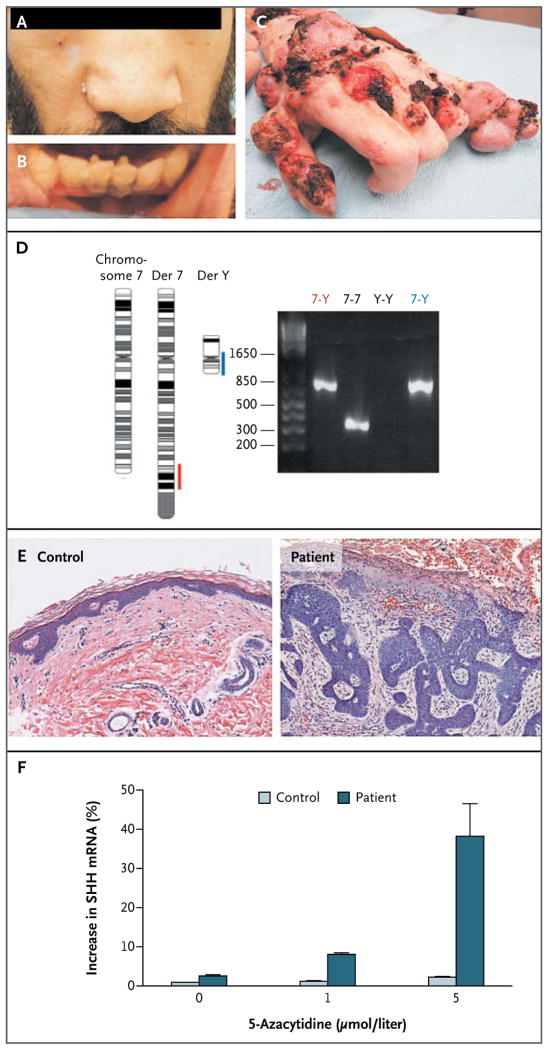

A 41-year-old man presented with several advanced basal-cell carcinomas on his head, trunk, and all four extremities. He had microcephaly, hypotelorism, a flat nasal bridge (Fig. 1A), and T-shaped incisors (Fig. 1B); these characteristics were suggestive of mild holoprosencephaly. His skin was normal at birth, and the onset of tumors occurred at about 9 years of age (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Clinical, Molecular, and Histologic Findings in a 41-Year-Old Man with Overexpression of the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) Gene.

Panel A shows a flat nasal bridge, and Panel B shows T-shaped midline teeth in a man with hypotelorism; these findings are characteristic of mild holoprosencephaly. Panel C shows a hand with widespread invasive and erosive basal-cell carcinomas. Panel D shows polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) confirmation of translocation between chromosome 7 (red bar) and chromosome Y (blue bar) with the use of primers that span parental wild-type 7–7 and Y–Y sequences; this shows that 7–7, 7–Y, and Y–7, but not Y–Y sequences are present in the patient’s chromosomes. Der denotes derivative chromosome. Panel E shows histologic characteristics of tissue from a control patient and the patient with a basal-cell carcinoma tumor. Panel F shows real-time PCR of sonic hedgehog (SHH) messenger RNA (mRNA) from keratinocytes obtained from a control patient and from the patient with a basal-cell carcinoma after treatment with various levels of the demethylating agent 5-azacyti-dine, which inhibits the DNA methylation that commonly occurs when cells and tumors are placed in cell culture. The level of mRNA was 40 times as high in the patient as in the control patient.

Testing was negative for mutations in PTCH1 and SMO associated with Gorlin’s syndrome. A previous karyotype analysis showed a balanced translocation between chromosomes 7 and Y,2 and this was confirmed. To characterize the molecular characteristics of the translocation breakpoint, we sequenced DNA purified from whole blood with the use of paired-end sequencing (with the Illumina Genome Analyzer II or HiSeq), generating 77 million reads (more than twice the physical coverage of the haplotype). This analysis revealed products indicating a translocation between chromosomes 7 and Y. (The products contained three instances of either a 7–Y junction or a Y–7 junction.)

Using the hg19 human genome reference sequence, we determined that the translocation resulted in the juxtaposition of position 19466894 on the Y chromosome and position 155747671 (the SHH locus) on chromosome 7 (Fig. 1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). The translocation fused the middle of the SHH promoter with Y-chromosome sequences, leaving intact 140 kb of regulatory sequences upstream of the SHH transcriptional start site.3 Juxtaposed Y-chromosome sequences derived from the “gene desert” between the azoospermia factor (AZF) regions AZFa and ZAFb, regions thought to contribute to sperm maturation.4 Analysis by means of poly-merase chain reaction confirmed the predicted junctions (Fig. 1D, and Fig. 2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

The translocation explains the mild holoprosencephaly; we suggest that aberrant control of SHH expression resulted in partial loss of SHH expression during development. It also explains the basal-cell carcinomas; we suggest that the mutant promoter drives SHH expression in the skin (Fig. 1E). Indeed, the patient’s tumors expressed higher levels of SHH protein (not shown) and in 5-azacytidine–treated, tumor-derived keratinocytes, significantly higher levels of SHH messenger RNA (Fig. 1F). SHH overexpression in this patient contrasts with the absence of SHH expression in common basal-cell carcinomas described in other patients with PTCH1 or SMO mutations.1 Given his large and aggressive tumor burden, the patient was enrolled in a phase 2 clinical trial (NCT00833417) that is described by Sekulic et al. in this issue of the Journal.5

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant (R01AR046786) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Rubin LL, de Sauvage FJ. Targeting the Hedgehog pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:1026–33. doi: 10.1038/nrd2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Develing AJ, Conte FA, Epstein CJ. A Y-autosome translocation 46,X,t(Yq-7q+) associated with multiple congenital anomalies. J Pediatr. 1973;82:495–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belloni E, Muenke M, Roessler E, et al. Identification of Sonic hedgehog as a candidate gene responsible for holoprosencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996;14:353–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skaletsky H, Kuroda-Kawaguchi T, Minx PJ, et al. The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature. 2003;423:825–37. doi: 10.1038/nature01722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.