Abstract

Aims:

The aim of this study is to evaluate the course of the inferior alveolar canal (IAC) including its frequently seen variations in relation to root apices and the cortices of the mandible at fixed pre-determined anatomic reference points using cone beam volumetric computed tomography (CBVCT).

Material and Methods:

This retrospective study utilized CBVCT images from 44 patients to obtain quantifiable data to localize the IAC. Measurements to the IAC were made from the buccal and lingual cortical plates (BCP/LCP), inferior border of the mandible and the root apices of the mandibular posterior teeth and canine. Descriptive analysis was used to map out the course of the IAC.

Results:

IACs were noted to course superiorly toward the root apices from the second molar to the first premolar and closer to the buccal cortical plate anteriorly. The canal was closest to the LCP at the level of the second molar. In 32.95% of the cases, the canal was seen at the level of the canine.

Conclusions:

This study indicates that caution needs to be exercised during endodontic surgical procedures in the mandible even at the level of the canine. CBVCT seems to provide an optimal, low-dose, 3D imaging modality to help address the complexities in canal configuration.

Keywords: Anterior loop, cone beam volumetric computed tomography, mandibular canal, mental foramen, radiograph

INTRODUCTION

Appropriate osteotomy and root-end resection are considered critical elements of apicoectomy of mandibular posterior teeth. Caution should be exercised during these procedures in order to prevent injury to the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle. The nerve along with the inferior alveolar artery and vein sends branches to innervate posterior teeth through the inferior alveolar canal (IAC) before splitting into incisive and mental components that innervate mandibular anterior teeth, the lower lip and gingiva.[1] Injury to the nerve during endodontic surgery is known to cause post-operative paresthesia or anesthesia.[1]

The continuation of the IAC anteriorly as the incisive canal has been reported in the literature.[1] The anterior loop refers to the extension of the inferior alveolar nerve, anterior to the mental foramen prior to exiting the canal.[2] It has also been described as the mental neurovascular bundle, which loops back to exit through the mental foramen as it traverses anteriorly and inferiorly. Paresthesia of the mental nerve from periapical infection of the canine has been reported in the literature.[3] Data in the literature has been used to develop guidelines for implant placement. These dictate that the most distal aspect of the implant is located at least 2 mm anterior to the mental foramen.[4] Applying similar guidelines to endodontic surgical treatment planning would imply that the anterior loop of the neurovascular canal is located in the area of the mandibular first premolar and the canine and injury to the nerve should be considered a risk while treatment planning for an endodontic surgical procedure in this area.[5]

Two-dimensional, conventional imaging techniques such as periapical and panoramic radiography have been used for evaluation of surgical sites. Localization of critical anatomic structures at the surgical site including an estimation of the location, size and configuration of the inferior alveolar nerve during mandibular surgery is usually difficult using conventional images.[6] Superimposition of overlying anatomy, distortion and magnification, presence of acquisition and processing artifacts and lack of information in the third dimension are some of the known drawbacks of this type of imaging.[7]

Three-dimensional (3D) imaging circumvents most of these drawbacks effectively; computed tomography (CT) has shown that the prevalence of the anterior loop of the IAC is around 7%.[8] Cone beam volumetric computed tomography (CBVCT), a relatively new imaging modality in dentistry, produces high-resolution, superimposition-free, artifact-free, non-magnified and undistorted 3D images of the maxillofacial anatomy that can be reformatted in any desired plane for interactive viewing and image manipulation.[9] The radiation dose is significantly less than that of conventional medical grade CT.[9,10,11]

In this study, previously acquired CBVCT studies were used in plotting the course of the inferior alveolar nerve and its anterior extensions, if any, to the level of the mandibular canine.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Institutional review board approval was sought to evaluate existing cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) records of 44 patients in the age group of 18-70 years acquired using the iCAT, (Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA, USA). These were randomly selected for the study. The selected patients had fully erupted mandibular posterior teeth and canines on both sides. CBCT studies showing evidence of severe periodontal disease, osteoradionecrosis or osteochemonecrosis, other hard tissue pathology, apical root resorption, and previous endodontic surgery were excluded from the study. The images were then reviewed by two examiners including a board certified oral and maxillofacial Radiologist and an Endodontist, using InVivo (Anatomage, San Jose, CA, USA) viewing software. Measurements from the IAC to the root apices of the first molar, first and second premolar and the canine was obtained from parasagittal reformatted images. Other measurements included the distance from the IAC to the buccal and lingual cortical plates (LCP) from the respective boundaries of the IAC, parallel to the X-axis on paracoronal slices at the above locations, as well as to the superior and inferior borders of the mandible, parallel to the Y-axis [Figure 1]. All measurements were repeated after a period of at least 2 weeks. The average of both readings for each site was recorded for analyses.

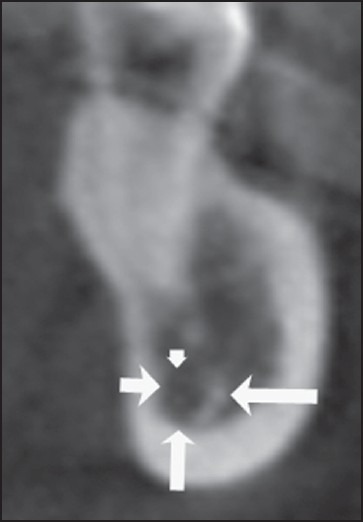

Figure 1.

Sagittal slice of a cone beam computed tomography image illustrating measurement of the inferior alveolar canal from the buccal and lingual cortical plates, inferior border of the mandible and apices of the teeth

RESULTS

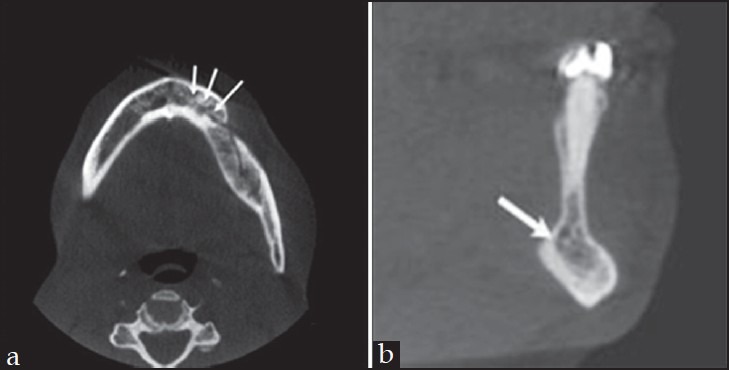

The IAC was noted to be closest to the buccal cortical plate (BCP) in the region of the premolars on both sides with a mean distance of 3.18 mm [Tables 1 and 2]. The canal courses toward the LCP and the inferior border of the mandible (Inferior BM) as it moves posteriorly toward the distal root of the second molars. Mean distance from the LCP to the canal at the level of the molars was 2.2 mm and the distance to the Inferior BM was 6.68 mm. Lateralization to the lingual varies to some degree. The canal was also closest to the distal root of the second molar although the distance from the roots of other teeth did not follow a set pattern. The roots of the second molar were in direct contact with the IAC in 20.4% of the cases on the right side and 13.6% of the cases on the left side. The presence of a canal in the region of the canine was noted in 15 images of the right side and 14 of the left side [Figure 2]. When present, the canal was centered in the body of the mandible, in the region of the canine in most of the cases. It was 3-4 mm away from the root of the canine.

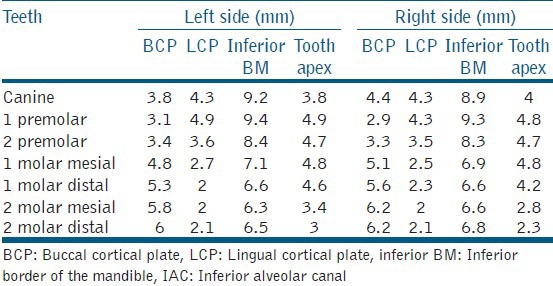

Table 1.

Mean distance of the IAC (in mm) from the BCP, LCP, inferior BM and the tooth root apex

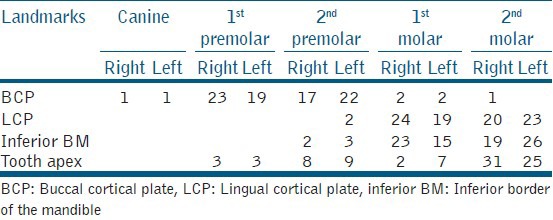

Table 2.

Number of cases at each measured location showing closest proximity to BCP, LCP, inferior BM and the tooth root apex

Figure 2.

(a) Axial view of a cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) image showing the presence of a neurovascular bundle (arrow) extending almost to the midline (b) Sagittal view of a CBCT image showing the presence of a neurovascular bundle (arrow) at the level of the canine

DISCUSSION

Previous researchers have examined the path of the inferior alveolar nerve in cadaver studies.[2,12,13,14] Yet other studies have attempted to determine the course of the inferior alveolar nerve through radiographic means instead of purely relying on cadaver dissections.[15,16,17] Many of these studies, however, suffer from a small sample sizes and the results may not be generalized to the population at large.[14,18] On the other hand, most such studies have noted that the canal and consequently the nerve do not maintain a constant position in the mandible, specifically in relation to roots of the lower teeth.[6] Such variability may then lead to unpredictable anatomic encounters at the time of surgery. More recently, complex 3D imaging such as CT has been utilized to establish the path of the IAC as well as other anatomic landmarks.[6,8,18,19] This cross-sectional imaging technique offers more detailed information to the clinician in 3D through interactive manipulation of the volume, thus providing an effective tool for diagnosis and treatment planning.[6] These studies have generally focused on the configuration of the IAC with respect to anatomic landmarks other than the roots of teeth, such as the buccal or LCPs or the canal path within the ramus as opposed to the body of the mandible where the roots lie.[17,18] However, in endodontic applications, the relationship of the IAC and its contents to the apices of teeth is important to adequately plan for surgical procedures.

The results of the study indicated the general course of the IAC, in relation to the buccal, lingual and Inferior BM, as it courses posteriorly from the canine to the distal root of the mandibular second molar. Our results confirm the findings of previous investigators who dissected cadaver jaws to study the course of the canal.[14] The proximity of the canal to the BCP in the region of the first and second premolar corresponds to the mental foramen. The canal was also found to be closest to the BCP in the region of the canine in one case, possibly indicating an anterior placement of the mental foramen. The canal was found to be closer to the LCP and the Inferior BM in the region of the molars. The measurement of the distance from the first molar root apices were in the range reported recently in a study using CBVCT scans.[6] The canal was closest to the second molar roots in 63.6% of the cases, on an average.

The significant finding in this study was the presence of the neurovascular bundle at the level of the mandibular canine in approximately 50% of the CBVCT scans that was studied. Various investigators using different techniques have studied the prevalence of the anterior loop and its length. The detection of anterior loops using panoramic radiographs reported incidence of 11-12%.[4,20] The use of radiopaque markers in panoramic films detected an anterior loop in 76% of dried skulls that were studied with the length ranging from 4.17 to 4.64 mm.[21] However, panoramic radiographs are known to have significant drawbacks that include variable distortion and magnification in the X, Y and Z-axis, positioning errors and double and ghost artifacts.[22] Measurements made from panoramic radiographs are not used for surgical planning therefore. Dissection of skulls to detect the anterior loop showed incidence ranging from 11% to 88%. The high percentage was reported by Neiva et al., who identified the loop by probing the mesial cortical wall of the mental canal.[23]

The use of periapical radiographs for detection of the anterior loop was evaluated using dissection to confirm the findings.[24] This study reported a significantly higher percentage detected in periapical radiographs (54%) when compared with dissection findings (11%). The high percentage of false positives was attributed to misinterpreting the incisive canal as part of the anterior loop. Similar studies comparing CT and dissection have not been performed further to validate these results.

Since the length of the anterior loop is reported to a range from 0 to 10 mm, it is difficult to distinguish between an anterior loop and an incisive canal from these studies.[25] The wide ranges of incidence reported by different researchers have led to the following guidelines for detection of an anterior extension of the IAC while treatment planning for an implant placement. After reflecting a full thickness flap, the mental foramen is located and an explorer is used to probe the configuration of the canal. If probing revealed a patent distal aspect, it was assumed that the canal had an anterior loop.[4]

The present study did not differentiate between the anterior loop and the incisive canal. From the surgeon's perspective, this differentiation is not significant. The mere presence of the neurovascular bundle at the level of the mandibular canine implies the need for caution during periapical surgery in the mandibular first premolar and the canine area. Hence it is important to determine if such an anatomic entity exists in patient at the time of surgery. With this study we hope to demonstrate the value of CBCT imaging in apical surgery. We believe that such 3-D image acquisition techniques will become the standard of care in the pre-operative evaluation of endodontic surgical patients in the near future, in select cases. Principles of as low as reasonably achievable when using radiation should always be followed while treatment planning. Larger clinical studies may be in order to establish the applications of CBCT in treatment planning in endodontics.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Mraiwa N, Jacobs R, Moerman P, Lambrichts I, van Steenberghe D, Quirynen M. Presence and course of the incisive canal in the human mandibular interforaminal region: Two-dimensional imaging versus anatomical observations. Surg Radiol Anat. 2003;25:416–23. doi: 10.1007/s00276-003-0152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moiseiwitsch JR. Avoiding the mental foramen during periapical surgery. J Endod. 1995;21:340–2. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozkan BT, Celik S, Durmus E. Paresthesia of the mental nerve stem from periapical infection of mandibular canine tooth: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:e28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misch CE, Crawford EA. Predictable mandibular nerve location — A clinical zone of safety. Int J Oral Implantol. 1990;7:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuzmanovic DV, Payne AG, Kieser JA, Dias GJ. Anterior loop of the mental nerve: A morphological and radiographic study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:464–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2003.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonton JD, Azevedo B, Schindler WG, Hargreaves KM. Age- and gender-related differences in the position of the inferior alveolar nerve by using cone beam computed tomography. J Endod. 2009;35:944–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huumonen S, Kvist T, Gröndahl K, Molander A. Diagnostic value of computed tomography in re-treatment of root fillings in maxillary molars. Int Endod J. 2006;39:827–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs R, Mraiwa N, vanSteenberghe D, Gijbels F, Quirynen M. Appearance, location, course, and morphology of the mandibular incisive canal: An assessment on spiral CT scan. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:322–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel S, Dawood A, Ford TP, Whaites E. The potential applications of cone beam computed tomography in the management of endodontic problems. Int Endod J. 2007;40:818–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamada Y, Kondoh T, Noguchi K, Iino M, Isono H, Ishii H, et al. Application of limited cone beam computed tomography to clinical assessment of alveolar bone grafting: A preliminary report. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2005;42:128–37. doi: 10.1597/03-035.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa Y, Kobayashi K, Ishii H, Mishima A, Ishii H, Asada K, et al. Preoperative application of limited cone beam computerized tomography as an assessment tool before minor oral surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:322–6. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter RB, Keen EN. The intramandibular course of the inferior alveolar nerve. J Anat. 1971;108:433–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narayana K, Vasudha S. Intraosseous course of the inferior alveolar (dental) nerve and its relative position in the mandible. Indian J Dent Res. 2004;15:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denio D, Torabinejad M, Bakland LK. Anatomical relationship of the mandibular canal to its surrounding structures in mature mandibles. J Endod. 1992;18:161–5. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Littner MM, Kaffe I, Tamse A, Dicapua P. Relationship between the apices of the lower molars and mandibular canal — A radiographic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62:595–602. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox NA. The position of the inferior dental canal and its relation to the mandibular second molar. Br Dent J. 1989;167:19–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadu SG, Penhall B, Townsend GC. Morphological variability of the human inferior alveolar nerve. Clin Anat. 1997;10:82–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1997)10:2<82::AID-CA2>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine MH, Goddard AL, Dodson TB. Inferior alveolar nerve canal position: A clinical and radiographic study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:470–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato I, Ueno R, Kawai T, Yosue T. Rare courses of the mandibular canal in the molar regions of the human mandible: A cadaveric study. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2005;82:95–101. doi: 10.2535/ofaj.82.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs R, Mraiwa N, Van Steenberghe D, Sanderink G, Quirynen M. Appearance of the mandibular incisive canal on panoramic radiographs. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004;26:329–33. doi: 10.1007/s00276-004-0242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arzouman MJ, Otis L, Kipnis V, Levine D. Observations of the anterior loop of the inferior alveolar canal. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1993;8:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeo DK, Freer TJ, Brockhurst PJ. Distortions in panoramic radiographs. Aust Orthod J. 2002;18:92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neiva RF, Gapski R, Wang HL. Morphometric analysis of implant-related anatomy in Caucasian skulls. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1061–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.8.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bavitz JB, Harn SD, Hansen CA, Lang M. An anatomical study of mental neurovascular bundle-implant relationships. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1993;8:563–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenstein G, Tarnow D. The mental foramen and nerve: Clinical and anatomical factors related to dental implant placement: A literature review. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1933–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]