Abstract

The relationships between lymphomas and their microenvironment appear to follow 3 major patterns: (1) an independent pattern; (2) a dependent pattern on deregulated interactions; and (3) a dependent pattern on regulated coexistence. Typical examples of the third pattern are hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated marginal zone lymphomas (MZLs) and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. In these lymphomas, a regulated coexistence of the malignant cells and the microenvironmental factors usually occurs. At least initially, however, tumor development and cell growth largely depend on external signals from the microenvironment, such as viral antigens, cytokines, and cell-cell interactions. The association between HCV infection and B-cell lymphomas is not completely defined, although this association has been demonstrated by epidemiological studies. MZL and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma are the histotypes most frequently associated with HCV infection. Many mechanisms have been proposed for explaining HCV-induced lymphomagenesis; antigenic stimulation by HCV seems to be fundamental in establishing B-cell expansion as observed in mixed cryoglobulinemia and in B-cell lymphomas. Recently, antiviral treatment has been proved to be effective in the treatment of HCV-associated indolent lymphomas. Importantly, clinically responses were linked to the eradication of the HCV-RNA, providing a strong argument in favor of a causative link between HCV and lymphoproliferation.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus-infection, B-cell lymphomas, Marginal zone lymphoma, Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas, Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, Microenvironment

Core tip: The relationships between lymphomas and their microenvironment appear to follow 3 major patterns: (1) an independent pattern; (2) a dependent pattern on deregulated interactions; and (3) a dependent pattern on regulated coexistence. The association between hepatitis C virus infection and B-cell lymphomas is not completely defined, although this association has been demonstrated by epidemiological studies.

INTRODUCTION

Genetic alterations and abnormal microenvironmental factors are involved in tumor development, cell growth and disease progression. Inflammatory cells and soluble mediators, i.e., cytokines and chemokines, are essential microenviromental factors that sustain cell growth and invasion, induce angiogenesis and suppress anti-tumor immune functions[1].

In multidimensional studies on hematolymphoid malignancies, a relevant clinical role of the tumor microenvironment has recently emerged, bringing new knowledge and suggesting new ideas and targets for treatment[2-5].

The relationships between lymphomas and their microenvironment appear to follow 3 major patterns: (1) an independent, largely autonomous pattern; (2) a dependent on deregulated interactions pattern; and (3) a dependent on regulated coexistence pattern[2]. A typical example of the first pattern is Burkitt lymphoma where all tumor cells proliferate because of permanent MYC gene activation. A typical example of the second pattern is classic Hodgkin lymphoma, where Reed-Sternberg cells escape the regulated cell growth- and proliferation-control. Typical examples of the third pattern are Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated marginal zone lymphomas (MZLs) and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. In this pattern, a regulated coexistence of the malignant cells and the microenvironment is reminiscent of the pattern that the normal counterpart B cells engage in with their respective microenvironment. At least initially, tumor development and cell growth largely depend on external signals from the microenvironment, such as viral antigens, cytokines, and cell-cell interactions[6].

HCV infection is a worldwide problem. There are important regional differences in the prevalence of HCV infection: the lowest rates are reported in Northern Europe while prevalence estimates exceed 2% in Italy, Japan, Egypt and southern parts of United States[7]. Among the carcinogenic viruses recognized by the recent International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) monograph Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human papilloma virus (HPV), human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-1), and Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) play a direct role in carcinogenesis encoding oncoproteins which are able to promote cellular transformation[8,9]. Conversely, HCV and Helicobacter pylori appear to have an indirect role, by inducing a chronic inflammation[10]. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has both a direct and indirect role in promoting hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); as a matter of fact, chronic HBV carriers can develop HCC without developing cirrhosis.

PATHOGENETIC ASPECTS

HCV infection is the cause of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Table 1). HCV infection has been also associated to a spectrum of extra-hepatic lymphoproliferative disorders including mixed cryoglobulinemia (MC)[11], the most well defined disorder associated with HCV infection, monoclonal gammopathies[12] and B-cell lymphomas[13]. HCV infection has been associated with B-cell low grade indolent lymphoma, especially of marginal zone origin, as well as with aggressive lymphomas, mainly diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) (Table 2). Authoritative studies have demonstrated that in HCV-infected patients with indolent lymphomas, eradication of HCV with antiviral treatment (AT) could directly induce lymphoma regression, providing a strong argument in favor of a causative link between HCV and lymphoproliferation[14].

Table 1.

Biological agents assessed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer Monographs Working Group[9]

| Group-1 agent | Cancers on which sufficient evidence in humans is based | Other sites with limited evidence in humans | Established mechanistic events |

| Epstein–Barr virus | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Burkitt lymphoma, Immune-suppression-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (nasal type), Hodgkin lymphoma | Gastric carcinoma1 Lympho-epithelioma-like carcinoma1 | Cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, genomic instability, cell migration |

| Hepatitis B virus | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Cholangiocarcinoma1, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma1 | Inflammation, liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis2 |

| Hepatitis C virus | Hepatocellular carcinoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma1 | Cholangiocarcinoma1 | Inflammation, liver cirrhosis, liver fibrosis |

| Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus | Kaposi sarcoma1, Primary effusion lymphoma1 | Multicentric Castleman’s disease1 | Cell proliferation, inhibition of apoptosis, genomic instability, cell migration |

| Human immunodeficiency virus, type 1 | Kaposi sarcoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma1, Cancer of the cervix1, anus1, conjunctiva1 | Cancer of the vulva1, vagina1, penis1, Non-melanoma skin cancer1, Hepatocellular carcinoma1 | Immunosuppression (indirect action) |

| Human papillomavirus type 16 (For the other types see Table 2) | Carcinoma of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, anus, oral cavity, oropharynx and tonsil | Cancer of the larynx | Immortalization, genomic instability, inhibition of DNA damage response, anti-apoptotic activity |

| Helicobacter pylori | Non-cardia gastric carcinoma, Low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue gastric lymphoma1 | Inflammation, oxidative stress, altered cellular turnover, changes in gene expression, methylation, mutation |

Newly identified link between virus and cancer. In red are highlighted the lymphoid proliferations;

HBV has both a direct and indirect role in promoting hepatocellular carcinoma. Modified and adapted from Bouvard et al[8].

Table 2.

Hepatitis C virus-associated indolent and aggressive lymphoid proliferations

| Subtype | Variant | Specific lymphoma sites |

| Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis | ||

| Tissue based monoclonal B cell and plasma cell proliferations of uncertain type | ||

| Lymphoplasmocytic lymphoma/WM | ||

| Chronic lymphocytic disorders (non CLL) | ||

| MZL | Splenic MZL | |

| Nodal MZL | ||

| MALT | Gastric | |

| Extranodal non gastric | ||

| Salivary gland | ||

| Skin | ||

| Orbit | ||

| Liver | ||

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

WM: Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia; CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MZL: Marginal zone lymphoma; MALT: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

INFLAMMATORY MICROENVIRONMENT

The liver is the main target of HCV infection and the major site of inflammatory events, including recruitment of inflammatory cells.

Occurrence of HCV enrichment in intrahepatic inflammatory infiltrates supports the notion that HCV is directly involved in the emergence and maintenance of these B-cell expansions[15]. Intrahepatic B-cell clonalities are invariably associated with extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection associated B-cell lymphomas.

HCV AND LYMPHOMAGENESIS

According to the recent IARC monograph on biological agents and carcinogenesis, the association between HCV infection and B-cell lymphomas is not completely defined[9]. This association has been demonstrated by epidemiological studies in highly endemic geographical areas[16]. The role of HCV infection in lymphomagenesis may be related to the chronic antigenic stimulation of B-cell response, similar to the well characterized induction of gastric MALT lymphoma development by Helicobacter pylori chronic infection[17]. In fact, chronic HCV infection may sustain a multi-step evolution from MC to overt low grade lymphoma and eventually to high-grade lymphoma[17]. During this process, additional genetic aberrations may induce independence from antigenic stimulation. The clonal component of MC is often an IgM with a rheumatoid factor activity that mirrors the expansion of a B-cell monoclonal population not only in bone marrow but also in liver. It has also been suggested that HCV antigens (NS3 and E7or E2) can play a role in lymphomagenesis[18,19]. Recently, it has been published that HCV-related cryoglobulins (either IgM and IgG) are mainly directed against core and NS3 proteins[20]. Chromosomal alterations could also play a role in development of HCV-related lymphoproliferative disorders: for instance, MC with or without lymphoma is characterized by translocation t(14; 18) with the overexpression of the antiapoptotic bcl-2 gene leading to prolonged B-cell survival[21].

Importantly, cytokines and chemokines (IFNγ, TNFα, CXCL13 and BAFF in MC[16], as well as osteopontin[22]) are involved in the mechanisms of HCV-induced lymphoproliferation.

HCV INFECTION AND SPECIFIC LYMPHOMAS

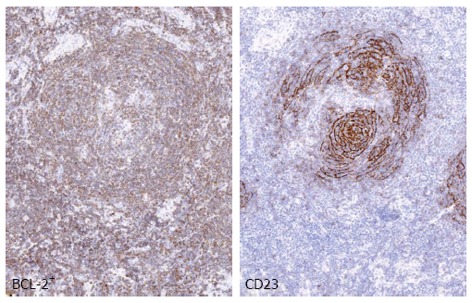

Within indolent lymphoma subtypes, the association with HCV infection has been best characterized in MZLs. Other infectious agents have been involved in the pathogenesis of specific types of MZLs. For examples Helicobacter pylori, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Chlamydophila psittaci have been involved in MALT lymphomas arising in stomach, skin and orbit, respectively[9]. Conversely, chronic stimulation by HCV plays a role in development of splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL) and primary nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Primary nodal marginal zone lymphoma is a distinct clinical-pathological subtype characterized by exclusive primary lymph node localization in the absence of extranodal site of involvement (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Nodal marginal zone lymphoma. The panel shows an example of nodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) with follicular colonization. BCL-2+ neoplastic cells surround and colonize the germinal center, whereas CD23 highlights the disrupted follicular dendritic cell meshwork. Images were acquired with the Olympus Dot. Slide Virtual microscopy system using an Olympus BX51 microscopy equipped with PLAN APO 2x/0.08 and UPLAN SApo 40x/0.95 objectives.

Splenic and nodal MZL are indolent B-cell lymphomas corresponding to post-germinal center memory B cells that are supposed to derive from marginal zone[23,24]. These entities share some morphologic and pathogenic features, but have distinctive clinical presentation, immunophenotype and molecular abnormalities. Histologically, when the marginal zone B cells surround normal follicles with benign mantle zones as a third outer layer, they produce a marginal zone pattern[25]. As the marginal zone cells extend outwards into the interfollicular areas, they form confluent clusters resulting in an interfollicular pattern or a diffuse pattern in the absence of any follicles at later stages of the disease[25]. The marginal zone cells may also grow inwards into the follicles and produce either partial or complete follicular colonization[25] (Figure 1).

Gastric and non-gastric extranodal MZL are typically indolent diseases of middle and advanced age; disseminated disease is present in nearly one-third of cases. Interestingly, three specific MALT lymphoma sites showed an elevated prevalence of HCV infection: salivary glands, skin and orbit[26]. The association of HCV infection and salivary glands lymphoma has been clearly demonstrated[27].

Moreover, a study on B-cell lymphoma in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and HCV infection reported an elevated occurrence of parotid involvement and a high proportion of MALT lymphomas with primary extranodal involvement (exocrine glands, liver, and stomach) (Table 2)[28].

Beside MZLs, also LPL/Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM) has been associated to HCV infection. However, this association is not completely defined. B-cell chronic lymphoproliferative disorders are defined as the miscellaneous category of lymproliferative disorders distinct from chronic lymphocytic. Association of these entities with HCV is not clear. Interestingly, monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), a pre-clinical condition characterized by an expansion of clonal B cells in the absence of frank lymphocytosis, was identified in nearly 30% of HCV-positive subjects with a significantly higher frequency than in the general population.

Recently, a retrospective study of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders associated with HCV infection found two poorly described groups of cases. The first featured disseminated MZL without splenic MZL features, defying the current MZL classification; the other consisted of monoclonal B lymphocytes in the peripheral blood, bone marrow or other tissues, with no clinical or histological evidence of lymphoma. This pattern requires proper identification in order to avoid the misdiagnosis of the lymphoma[29].

Despite the classical association of HCV with indolent lymphoma, aggressive lymphoma, in particular DLBCL, are emerging as diseases linked to HCV infection. Patients affected by HCV-associated DLBCL display specific presentation with respect to HCV-negative DLBCL. In particular, residual signs of low-grade lymphoma and extranodal disease such as spleen are more frequently detected in HCV-associated DLBCL cases in comparison with HCV-negative DLBCL[9]. Unlike indolent B-cell lymphoma, AT seems not to play a central role in the first-line approach for HCV-associated DLBCL, because lymphoma cells are most likely to be independent from chronic antigenic stimulation due to the acquisition of additional oncogenic lesions. For this reason, HCV-associated DLBCL patients have to be treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy coupled with rituximab.

CONCLUSION

Many epidemiological studies have provided evidence that HCV infection is associated with development of indolent and aggressive B-cell lymphoma[30,31]. However, the causal association between HCV infection and B-cell lymphomas is not completely defined. The similarities shared by rearranged Ig genes present in B cells from patients with type II MC and malignant B-cells from HCV-positive patients affected by B-cell lymphoma support the possibility that the antigens that promote type II MC and B-cell lymphoma in HCV-positive patients are the same[32,33]. These similarities also suggest that type II MC may be a precursor of B-cell lymphoma[34]. Type II MC probably plays a central role in the development of B-cell lymphoma in HCV-positive patients with Sjögren’s syndrome[35].

Three hypothetic models have emerged to understand the molecular mechanisms of HCV-associated lymphoma development: (1) continuous external stimulation of lymphocyte receptors by viral antigens and consecutive proliferation; (2) direct role of HCV replication and expression in infected B-cells; and (3) permanent B-cell damage, e.g., mutation of tumor suppressor genes, caused by a transiently intracellular virus (“hit and run” theory)[9,36]. Other non exclusive hypotheses have been proposed over the past two decades. These hypotheses have variously emphasized the important role played by chromosomal aberrations, cytokines, or microRNA molecules[37]. However, the mechanisms by which B-cell lymphomas are induced by HCV remain the subject of debate.

Footnotes

Supported by An Institutional grant from Centro di Riferimento Oncologico Aviano for an intramural project “Agenti Infettivi e Tumori” to Carbone A; and an Institutional grant from the Fondazione IRCSS Istituto Nazionale Tumori Milano “Validation of a new algorithm for HPV status assessment in head and neck carcinoma” to Gloghini A

P- Reviewers: Anand BS, Quer J S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burger JA, Ghia P, Rosenwald A, Caligaris-Cappio F. The microenvironment in mature B-cell malignancies: a target for new treatment strategies. Blood. 2009;114:3367–3375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dave SS, Wright G, Tan B, Rosenwald A, Gascoyne RD, Chan WC, Fisher RI, Braziel RM, Rimsza LM, Grogan TM, et al. Prediction of survival in follicular lymphoma based on molecular features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2159–2169. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenz G, Wright G, Dave S, Kohlmann A, Xiao W, Powell J, Zhao H, Xu W, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, et al. Gene expression signatures predict overall survival in diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with Rituximab and Chop-like chemotherapy. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts Blood. 2007;110:348. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, Farinha P, Han G, Nayar T, Delaney A, Jones SJ, Iqbal J, Weisenburger DD, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:875–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbone A, Cesarman E, Spina M, Gloghini A, Schulz TF. HIV-associated lymphomas and gamma-herpesviruses. Blood. 2009;113:1213–1224. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558–567. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, et al. A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–322. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100:1–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone A, De Paoli P. Cancers related to viral agents that have a direct role in carcinogenesis: pathological and diagnostic techniques. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:680–686. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agnello V, Chung RT, Kaplan LM. A role for hepatitis C virus infection in type II cryoglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1490–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211193272104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreone P, Gramenzi A, Cursaro C, Bernardi M, Zignego AL. Monoclonal gammopathy in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Blood. 1996;88:1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferri C, Caracciolo F, Zignego AL, La Civita L, Monti M, Longombardo G, Lombardini F, Greco F, Capochiani E, Mazzoni A. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 1994;88:392–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb05036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermine O, Lefrère F, Bronowicki JP, Mariette X, Jondeau K, Eclache-Saudreau V, Delmas B, Valensi F, Cacoub P, Brechot C, et al. Regression of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes after treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:89–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sansonno D, Lauletta G, De Re V, Tucci FA, Gatti P, Racanelli V, Boiocchi M, Dammacco F. Intrahepatic B cell clonal expansions and extrahepatic manifestations of chronic HCV infection. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:126–136. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arcaini L. HCV associated lymphomas. Hematology Education: the education program for the annual congress of the European Hematology Association. Hematologica. 2013;7:413–422. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suarez F, Lortholary O, Hermine O, Lecuit M. Infection-associated lymphomas derived from marginal zone B cells: a model of antigen-driven lymphoproliferation. Blood. 2006;107:3034–3044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Re V, Sansonno D, Simula MP, Caggiari L, Gasparotto D, Fabris M, Tucci FA, Racanelli V, Talamini R, Campagnolo M, et al. HCV-NS3 and IgG-Fc crossreactive IgM in patients with type II mixed cryoglobulinemia and B-cell clonal proliferations. Leukemia. 2006;20:1145–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pileri P, Uematsu Y, Campagnoli S, Galli G, Falugi F, Petracca R, Weiner AJ, Houghton M, Rosa D, Grandi G, et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science. 1998;282:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minopetrou M, Hadziyannis E, Deutsch M, Tampaki M, Georgiadou A, Dimopoulou E, Vassilopoulos D, Koskinas J. Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cryoglobulinemia: cryoglobulin type and anti-HCV profile. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:698–703. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00720-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zignego AL, Ferri C, Giannelli F, Giannini C, Caini P, Monti M, Marrocchi ME, Di Pietro E, La Villa G, Laffi G, et al. Prevalence of bcl-2 rearrangement in patients with hepatitis C virus-related mixed cryoglobulinemia with or without B-cell lymphomas. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:571–580. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Libra M, Indelicato M, De Re V, Zignego AL, Chiocchetti A, Malaponte G, Dianzani U, Nicoletti F, Stivala F, McCubrey JA, et al. Elevated Serum Levels of Osteopontin in HCV-Associated Lymphoproliferative Disorders. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:1192–1194. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.11.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaacson PG, Chott A, Nakamura S, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris NL, Swerdlow SH. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008. pp. 214–217. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campo E, Pileri SA, Jaffe ES, Muller-Hermelink HK, Nathwani BN. Nodal marginal zone lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008. pp. 218–219. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rezk SA, Nathwani BN, Zhao X, Weiss LM. Follicular dendritic cells: origin, function, and different disease-associated patterns. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:937–950. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arcaini L, Burcheri S, Rossi A, Paulli M, Bruno R, Passamonti F, Brusamolino E, Molteni A, Pulsoni A, Cox MC, et al. Prevalence of HCV infection in nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:346–350. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ambrosetti A, Zanotti R, Pattaro C, Lenzi L, Chilosi M, Caramaschi P, Arcaini L, Pasini F, Biasi D, Orlandi E, et al. Most cases of primary salivary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma are associated either with Sjoegren syndrome or hepatitis C virus infection. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:43–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos-Casals M, la Civita L, de Vita S, Solans R, Luppi M, Medina F, Caramaschi P, Fadda P, de Marchi G, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Characterization of B cell lymphoma in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and hepatitis C virus infection. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:161–170. doi: 10.1002/art.22476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mollejo M, Menárguez J, Guisado-Vasco P, Bento L, Algara P, Montes-Moreno S, Rodriguez-Pinilla MS, Cruz MA, Casado F, Montalbán C, et al. Hepatitis C virus-related lymphoproliferative disorders encompass a broader clinical and morphological spectrum than previously recognized: a clinicopathological study. Mod Pathol. 2013:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mele A, Pulsoni A, Bianco E, Musto P, Szklo A, Sanpaolo MG, Iannitto E, De Renzo A, Martino B, Liso V, et al. Hepatitis C virus and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas: an Italian multicenter case-control study. Blood. 2003;102:996–999. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Germanidis G, haioun C, Dhumeaux D, Reyes F, Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus infection, mixed cryoglobulinemia, and B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hepatology. 1999;30:822–823. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Vita S, Sansonno D, Dolcetti R, Ferraccioli G, Carbone A, Cornacchiulo V, Santini G, Crovatto M, Gloghini A, Dammacco F, et al. Hepatitis C virus within a malignant lymphoma lesion in the course of type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 1995;86:1887–1892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sansonno D, De Vita S, Cornacchiulo V, Carbone A, Boiocchi M, Dammacco F. Detection and distribution of hepatitis C virus-related proteins in lymph nodes of patients with type II mixed cryoglobulinemia and neoplastic or non-neoplastic lymphoproliferation. Blood. 1996;88:4638–4645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dammacco F, Gatti P, Sansonno D. Hepatitis C virus infection, mixed cryoglobulinemia, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an emerging picture. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;31:463–476. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mariette X. Lymphomas complicating Sjögren’s syndrome and hepatitis C virus infection may share a common pathogenesis: chronic stimulation of rheumatoid factor B cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1007–1010. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peveling-Oberhag J, Arcaini L, Hansmann ML, Zeuzem S. Hepatitis C-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Epidemiology, molecular signature and clinical management. J Hepatol. 2013;59:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zignego AL, Gragnani L, Giannini C, Laffi G. The hepatitis C virus infection as a systemic disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7 Suppl 3:S201–S208. doi: 10.1007/s11739-012-0825-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]