Abstract

Background

Numerous techniques for determining the flexibility of the scoliotic cure have been invented. Our contribution includes combining traction and translation forces; we introduced a new radiographic technique that can be claimed to be capable of a far more precise prediction of the scoliotic curve flexibility.

Methods

In this study, we compared the flexibility rate obtained on standard fulcrum bending radiographs with modified ones in 50 consecutive patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (78 curves) who had referred to our clinics from September 2009 to July 2012. In this new technique, we added traction force to the upside extremities. Then, flexibility rate of the two methods was compared statistically.

Results

The study included 50 cases (43 female and 7 male) aged 10–17 (14.5 ± 2.1 years) comprising 78 scoliotic curves. Curves magnitude varied from 25° to 135° (61.4° ± 21.3°). The mean flexibility rate with standard fulcrum bending radiograph was 38.8% ± 20%. This index increased to 58.3% ± 22.2% (which is statistically significant, p < 0.0005) as a result of implementing the modified fulcrum bending method. Excluding the proximal thoracic curves due to the limited number of the cases, the difference between flexibility rate with this new technique in main thoracic and thoracolumbar/lumbar curves is not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

The modified fulcrum bending method we introduced has some inevitable disadvantages; however, in the era of modern and vigorous segmental spinal instrumentation, with combining traction and translation forces in their best biomechanical state, it can demonstrate the scoliotic curve flexibility much more efficiently.

Keywords: Scoliosis, Flexibility, Radiography, Fulcrum bending

1. Background

Predicting the curve flexibility before surgical operation in the patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is of utmost important.1 With the preoperative acknowledgment of this index, the surgeon can predict the correctability rate, numbers and levels of the motion segments to be fused in order to correctly balance and selectively fuse the spine, and magnitude of the corrective force that can be applied safely during this operation.2

For this purpose, numerous techniques for determining the flexibility of the scoliotic curve have been invented. These include: supine,3 standing,4 standing or supine side bending,5 push-prone,6 traction (with or without general anesthesia),1,7 and fulcrum bending8,9 radiographs. Any one of these methods has its own advantages and disadvantages copiously explained in literature.1,3–10

According to the basic biomechanical study carried out by White and Panjabi, the best way to correct the scoliotic curve is a combination of axial and transverse loading in such a way that axial loading (traction) is more effective in severe and transverse loading is the main corrective force in small curves.11 The threshold between these two was a curve of 53° magnitude. In addition, from the biomechanical stand point of the orthotic treatment for spinal deformities, the effects of curve correction and transverse support are additive in order to increase the critical load.12 Curve correction effect is more significant for larger curves as the transverse load is more effective for smaller ones. In fact these two forces could be analogized with traction force and fulcrum bending (or push maneuver in push-prone radiograph), respectively. Therefore, if we can invent a combined technique to apply both forces simultaneously, it may reflect the curve flexibility better than others, at least theoretically.

Although currently supine bending or traction radiographs are more commonly performed, these techniques belong to the Harrington instrumentation era. In the time of modern, vigorous, and segmental spinal instruments like pedicular screw systems, we need more aggressive flexibility radiographic techniques to determine the curve flexibility. In this study, we introduced a new combined radiographic technique we claimed it could predict the scoliotic curve flexibility much more precisely. We also compared the flexibility rate of this new technique with the standard fulcrum bending radiograph.

2. Methods

In this study, we compared the flexibility rate obtained on standard fulcrum bending radiograph with modified ones in 50 consecutive patients (78 curves) referred to one of our two clinics from September 2009 to July 2012. Our criteria allowed the inclusion of the patients in the age range of ten years to seventeen years and eleven months with the scoliotic curve more than 10° and confirmed diagnosis of AIS. The patients with non-idiopathic causes or the ones with a history of scoliotic surgery in the past were excluded.

An institutional review board approval was obtained at the beginning. Informed consent was taken from all the patients after full explanation about the probable harmful effects of this amount of radiation and the technique itself. All of the radiographs were taken at the radiographic department of Imam Reza university hospital and with a similar technique. The final radiographic measurement was carried out by both spine surgeons of the team (FOK and EGH), separately and finally the mean value was assumed.

The technique of standard fulcrum bending radiographs was explained in detail, previously.8 In the modified technique we introduced (Fig. 1), the patient was placed in true lateral decubitus position over an appropriately sized fulcrum. This means a sized fulcrum that can lift the shoulder and pelvis off the radiologic table for thoracic and lumbar scoliotic curves, respectively. The fulcrum must be wrapped in extra padding layers so that the patient feels completely comfortable.

Fig. 1.

The manner to take modified fulcrum bending radiograph. It is necessary to maintain the position for at least 1 min before radiation exposure in order to relieve muscular spasm.

The place of the fulcrum was determined according to the biomechanical principles of the orthotic treatment. This meant placing the fulcrum directly under the apex of the lumbar and the rib connected to the apex of the thoracic curves as in standard fulcrum bending technique. The apices were recognized upon posteroanterior standing radiograph (Fig. 2a). We applied the traction forces indirectly and through the upside upper and lower extremities of the patient. The maneuver was carried out by the two of highly trained orthopedic staff. We believe this more laterally placed traction vectors on the concave side of the curve probably corrects it much more effectively compared to the traction forces that mediates directly through the spinal column itself.

Fig. 2.

a (left): Standing posteroanterior radiograph. Standing posteroanterior radiograph of the same patient on Fig. 1 (case 50). The patient has right T4–T11 (apex T8) and left T12–L5 (apex L3) scoliosis of 87° and 74°, respectively. b (right): Modified fulcrum bending radiograph. Modified fulcrum bending radiograph of the lumbar curve pertaining to the same patient on Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 (case 50). Left lumbar scoliosis was corrected from 74° to 30° on the modified one.

In order to significantly reduce the active muscular resistance, not only the patient was requested to allow her or his muscles to relax completely, but also the position had been maintained for at least 1 min before the radiography took place. In this moment, the patient must be in true lateral position (Fig. 2b).

We obtained flexibility rate by the following formula:

We did not compare the results of flexibility rates with those of the corrective rate obtained after surgery, because in that way we had to analyze only the major curves need surgery. Indeed, the major goal of this study has been assessing the results of flexibility rate obtained by this new technique on both small and large idiopathic curves. Moreover, another reason was the fact that a variety of surgical techniques that present among different spine surgeons certainly affects the correctability rate and this bias with no doubt would change the corrective rate obtained with postoperative radiographs.

2.1. Statistics

We used SPSS version 11.5 for statistical analysis. The Pearson correlation analysis was used for the correlation and paired t-test for comparison. p value less than 5% was considered as a statistical significant.

3. Results

We studied 50 cases (43 female and 7 male) with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis aged 10–17 (14.5 ± 2.1 years). These comprised 78 scoliotic curves; 3 proximal thoracic (PT), 48 main thoracic (MT), and 27 thoracolumbar/lumbar (TL/L) curves according to Lenke definition. Curves magnitude varied from 25° to 135° (61.4° ± 21.3°).

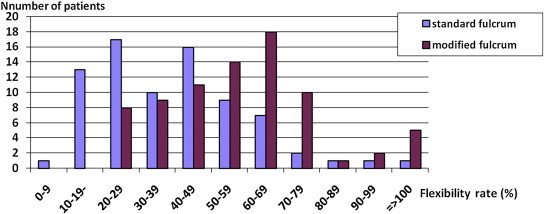

Distribution of fulcrum flexibility measurements in our patients based on standard and modified fulcrum bending radiographs was depicted in Fig. 3. The mean flexibility rate with standard fulcrum bending radiograph was 38.8% ± 20%, while with modified fulcrum bending method this index increased to 58.3% ± 22.2% (statistically significant, p < 0.0005).

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of flexibility rate. Flexibility rate in the patients with AIS obtained by standard and modified fulcrum bending radiographs.

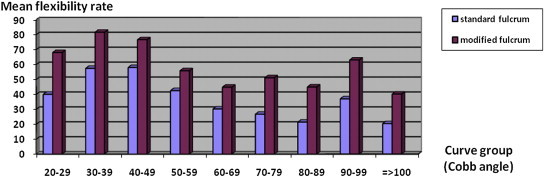

In order to compare flexibility rate obtained by these two radiographs in various curve angles, we placed our patients in 9 groups of 10° increment of Cobb angle (Fig. 4). Then, we calculated the mean flexibility rate of each group based on standard and modified fulcrum bending radiographs. The mean flexibility rates with modified technique in PT, MT, and TL/L curves were 70.3% ± 25%, 56.4% ± 21.2% and 60.4% ± 24%, respectively (excluding the PT curves due to the limited number of the cases, the difference between flexibility rate with modified technique in MT and TL/L curves is not statistically significant, p > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Flexibility rate of various scoliotic curves. The correlation of curve magnitude and flexibility rate with the two separate radiographic fulcrum bending techniques.

4. Discussion

The traditional supine bending films need patient cooperation for actively bend laterally while exerting the maximal force. Therefore, in patients who are mentally retarded, unreliable, or neuromuscular related cases, this method is obviously inapplicable.

In 1996, Soucacos assessed scoliotic curve flexibility in 49 cases with idiopathic scoliosis by supine traction radiography to predict the least correctability can be expected by Harrington distraction systems.13 In the method they used, the traction vectors were applied to the ankle and wrist, similar to the sites we chose to apply the traction forces on. Finally, they offered that simple manual traction can do this duty relatively well. Clearly, this maneuver belongs to the Harrington era and cannot be used today.

Some authors by applying different study designs have found out that in demonstrating curve flexibility, supine bending films are more effective than traction films for smaller curves and vice versa.1 These studies also confirmed the White and Panjabi's biomechanical work.11 In 2004, however, Davis questioned the reliability of supine bending radiographs in evaluating the curve flexibility in favor of traction radiography performed under general anesthesia. Actually, in their technical manner, they not only applied traction, but also translational force to the apex of the curve with a lead gloved hand while the patient was under anesthesia.7

And as for the role of general anesthesia in this respect, Hamzaoglu in a prospective study evaluated the different radiologic techniques on 34 patients with AIS. He concluded that in rigid curves larger than 65°, traction views with the patients under general anesthesia show the most flexibility rate.2

Another factor that has a determining role in the results is the location of the scoliotic curve. Klepps, in a prospective effectiveness analysis of different flexibility radiographs on 46 consecutive patients with AIS concluded that in main thoracic curves, fulcrum bending radiographs are the most accurate but in upper thoracic and thoracolumbar/lumbar curves, supine bending radiographs should continued to be used.14 The findings of Fei and co-authors are also confirmatory.15

Later, Watanabe in a prospective study on 229 consecutive patients with AIS determined the corrective ability of traction or side bending radiographs in relation with Cobb angle (in standing position), age, apical level, and number of involved vertebra in the curve.10 In PT curves, if the Cobb angle is more than 40°, traction view is preferred. In MT curves, the conditions under which this technique is preferred again are age of less than 15, Cobb more than 60°, apical level between T4-8/9, normal kyphosis and <7 involved vertebrae. In the TL/L curves, supine bending views are usually better excepting Cobb angles of more than 60° and apical level of T12–L1.

According to our knowledge from literature there is no clear explanation of how to take and standardize a traction radiograph. How much force is necessary? Does the traction force have to be applied directly to the skull (by manual or halter traction) and pelvic girdle or indirectly to the upper and lower extremities instead, as we did? What is the best position for it? In any way, it is obvious that axial traction applied to the alert person is much safer than the case under general anesthesia.

Like other flexibility radiographs, the technique we introduced has also several disadvantages. First, a trained staff or physician is needed for applying traction and obtaining proper position and as a result, the personnel are exposed to the radiation. Second, there is no practical way to standardize the magnitude or threshold of the traction force. One of the other major limitations of our study was the lack of assessment of its clinical application. Without the surgical outcome analysis, the efficacy of this new technique could not be validated. This certainly should be done in the future. Besides, because it is not approved ethically to take numerous radiographs from the patients, we also could not compare this method with other flexibility tests including supine bending or traction films. Although, theoretically these maneuvers are somewhat inside this new technique, it needs to be proven in future.

Contraindications of modified fulcrum bending radiograph include the patients with osteopenia (e.g. osteomalacia) and those suspected of spinal or shoulder instability. In osteopenic cases, there is an increased risk of rib fracture on the roll with this relatively aggressive maneuver.

5. Conclusions

Although the modified fulcrum bending method we introduced has some inevitable disadvantages, in the era of modern and vigorous segmental spinal instrumentation, with combining traction and translation forces in their best biomechanical state, it can demonstrate the scoliotic curve flexibility more efficiently.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Alamdaran A, MD (radiologist) for his valuable advice and participation in conducting the process.

References

- 1.Polly D.W., Sturm P.F. Traction versus supine side bending. Which technique best determines curve flexibility? Spine. 1998;23:804–808. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199804010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamzaoglu A., Talu U., Tezer M. Assessment of curve flexibility in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2005;30:1637–1642. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000170580.92177.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheh G., Lenke L.G., Lehman R.A., Jr. The reliability of preoperative supine radiographs to predict the amount of curve flexibility in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2007 Nov 15;32:2668–2672. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815a5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clamp J.A., Andrews J.R., Grevitt M.P. A study of the radiologic predictors of curve flexibility in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008 May;21:213–215. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181379f19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Transfeldt E.E., Winter R.B. September 23–26, 1992. Comparison of the supine and standing side bending X-rays in idiopathic scoliosis to determine curve flexibility and vertebral derotation. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Scoliosis Research Society, Kansas City, Missouri. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vedantam R., Lenke L.G., Bridwell K.H. Comparison of push-prone and lateral-bending radiographs for predicting postoperative coronal alignment in thoracolumbar and lumbar scoliotic curves. Spine. 2000 Jan;25:76–81. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200001010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis B.J., Gadgil A., Trivedi J. Traction radiography performed under general anesthetic: a new technique for assessing idiopathic scoliosis curves. Spine. 2004 Nov 1;29:2466–2470. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000143109.45744.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luk K.D., Don A.S., Chong C.S. Selection of fusion levels in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis using fulcrum bending prediction: a prospective study. Spine. 2008 Sep 15;33:2192–2198. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817bd86a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay D., Izatt M.T., Adam C.J. The use of fulcrum bending radiographs in anterior thoracic scoliosis correction: a consecutive series of 90 patients. Spine. 2008 Apr 20;33:999–1005. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816c8343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe K., Kawakami N., Nishiwaki Y. Traction versus supine bending radiographs in determining flexibility: what factors influence these techniques? Spine. 2007 Nov 1;32:2604–2609. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318158cbcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White A.A., Panjabi M.M. Practical biomechanics of scoliosis and kyphosis. In: White A.A., Panjabi M.M., editors. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine. 2nd ed. J.B. Lippincott Co.; Philadelphia: 1990. pp. 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavin T.M., Patwardhan A.G., Bunch W.H. Principles and components of spinal orthoses. In: Golberg B., Hsu J.D., editors. Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices. 3rd ed. Mosby; United States of America: 1996. pp. 155–194. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soucacos P.K., Soucacos P.N., Beris A.E. Scoliosis elasticity assessed by manual traction: 49 juvenile and adolescent idiopathic cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996 Apr;67:169–172. doi: 10.3109/17453679608994665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klepps S.J., Lenke L.G., Bridwell K.H. Prospective comparison of flexibility radiographs in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2001 Mar 1;26:E74–E79. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200103010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fei Q., Wang Y.P., Qiu G.X. Assessment of curve flexibility in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis before operation. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007 Sep 18;87:2484–2488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]