Human AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) belongs to the DNase I-like superfamily of enzymes that require divalent cation(s) to catalyze phosphoryl-transfer reactions. A new 1.92 Å resolution crystal structure of APE1 reveals ideal octahedral coordination of a single Mg2+ ion and informs on the role of this essential cofactor.

Keywords: apurinic/apyrimidinic DNA, base-excision repair, nucleases, phosphoryl transfer

Abstract

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) mediates the repair of abasic sites and other DNA lesions and is essential for base-excision repair and strand-break repair pathways. APE1 hydrolyzes the phosphodiester bond at abasic sites, producing 5′-deoxyribose phosphate and the 3′-OH primer needed for repair synthesis. It also has additional repair activities, including the removal of 3′-blocking groups. APE1 is a powerful enzyme that absolutely requires Mg2+, but the stoichiometry and catalytic function of the divalent cation remain unresolved for APE1 and for other enzymes in the DNase I superfamily. Previously reported structures of DNA-free APE1 contained either Sm3+ or Pb2+ in the active site. However, these are poor surrogates for Mg2+ because Sm3+ is not a cofactor and Pb2+ inhibits APE1, and their coordination geometry is expected to differ from that of Mg2+. A crystal structure of human APE1 was solved at 1.92 Å resolution with a single Mg2+ ion in the active site. The structure reveals ideal octahedral coordination of Mg2+ via two carboxylate groups and four water molecules. One residue that coordinates Mg2+ directly and two that bind inner-sphere water molecules are strictly conserved in the DNase I superfamily. This structure, together with a recent structure of the enzyme–product complex, inform on the stoichiometry and the role of Mg2+ in APE1-catalyzed reactions.

1. Introduction

Mammalian apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease 1 (APE1) is required for the repair of abasic sites and other DNA lesions and is an essential element of the base-excision repair (BER) and strand-break repair pathways (Kane & Linn, 1981 ▶; Robson & Hickson, 1991 ▶; Demple et al., 1991 ▶). APE1 also has important functions in transcriptional regulation and is sometimes referred to as Ref-1 (Bhakat et al., 2009 ▶). Abasic sites are mutagenic and cytotoxic lesions that arise by spontaneous rupture of the N-glycosylic bond or the action of DNA glycosylases, which excise damaged bases from DNA (Loeb, 1985 ▶; Lindahl, 1993 ▶). APE1 hydrolyzes the phosphodiester bond at abasic sites, producing 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) and the 3′-OH primer needed for repair synthesis, and is the major AP endonuclease in mammalian cells (Demple & Harrison, 1994 ▶; Robson & Hickson, 1991 ▶; Chen et al., 1991 ▶). APE1 also mediates the repair of single-strand and double-strand breaks by removing 3′-blocking groups (fragmented sugar moieties), again giving a 3′-OH for subsequent repair (Izumi et al., 2000 ▶; Parsons et al., 2004 ▶). The repair activity of APE1 is essential for embryonic development and cell viability (Xanthoudakis et al., 1996 ▶; Fung & Demple, 2005 ▶; Izumi et al., 2005 ▶), and APE1 repairs damage caused by many clinically relevant anticancer agents, including AP sites and 3′-blocking groups generated by ionizing radiation and bleomycin (Chaudhry et al., 1999 ▶; Parsons et al., 2004 ▶; Fung & Demple, 2010 ▶; Chen & Stubbe, 2005 ▶). Thus, APE1 is an important target for the development of novel anticancer agents or adjuvants to currently used agents (Adhikari et al., 2008 ▶; Abbotts & Madhusudan, 2010 ▶) and it is important to understand its structure and catalytic mechanism at the highest level of detail.

APE1 possesses a remarkable degree of catalytic power and Mg2+ is an essential cofactor. While Mn2+ can also serve as a cofactor for APE1, it is not as effective as Mg2+ (Kane & Linn, 1981 ▶; Barzilay et al., 1995 ▶). The AP endonuclease activity of APE1 is potent, with a maximal rate for the chemical step of at least 850 s−1 (Maher & Bloom, 2007 ▶). In contrast, the non-enzymatic hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds in DNA is extremely slow, occurring with a half-life of 100 000 years (Radzicka & Wolfenden, 1995 ▶). Thus, APE1 exhibits a rate enhancement of 1016 for its endonuclease activity. Previous studies show that this robust activity can be fully suppressed by rigorous chelation of Mg2+ (Erzberger & Wilson, 1999 ▶; Maher & Bloom, 2007 ▶), indicating that this cofactor is essential for catalysis. Notably, APE1 belongs to the large DNase I superfamily of endonuclease, exonuclease and phosphatase (EEP) enzymes (Dlakić, 2000 ▶). The important catalytic residues are strictly conserved in this superfamily, including several that coordinate Mg2+ (or other divalent cation) either directly or by an inner-sphere water molecule. However, the stoichiometry and catalytic function of the divalent cation remain unresolved for APE1 and other enzymes in the DNase I superfamily. Identifying the binding sites and function(s) of metals remains an important problem in biology (Yannone et al., 2012 ▶).

To date, three different crystal structures have been reported in the literature for DNA-free human APE1, but they contain a surrogate metal rather than the native Mg2+ cofactor. A structure of Mg2+-bound APE1 was deposited in the Protein Data Bank in 2011 (PDB entry 3u8u; R. Agarwal & M. D. Naidu, unpublished work), but no paper describing this structure has appeared in the literature. The first reported structure contained one Sm3+ ion in the active site (Gorman et al., 1997 ▶) and this was taken to represent the binding site for Mg2+, based on similarity to a structure of Mn2+-bound exonuclease III, the prokaryotic homolog of APE1 (Mol et al., 1995 ▶). The metal-binding site identified in this first APE1 structure, often referred to as the ‘A’ site, is consistent with the binding site observed for Mg2+ or other divalent metals in structures of other enzymes within the large DNase I superfamily (Suck & Oefner, 1986 ▶; Dlakić, 2000 ▶). Subsequently, two additional structures of DNA-free APE1 were reported with Pb2+ ions in the active site (Beernink et al., 2001 ▶). Both of these structures have a Pb2+ ion in the A site and one has a second Pb2+ ion, in a location that is referred to as the ‘B’ site, coordinated by three residues that are essential for catalysis and strictly conserved in the DNase I superfamily (Asp210, Asn212 and His309; Beernink et al., 2001 ▶). This finding raised the possibility that APE1 and related enzymes require two divalent metals for catalysis. In this two-metal mechanism, the B-site metal would serve to stabilize the hydroxide nucleophile, i.e. lower the pK a for the nucleophilic water molecule. However, subsequent studies found that Pb2+ is a potent inhibitor of APE1 (McNeill et al., 2004 ▶, 2007 ▶) and this inhibition could reflect a perturbation of the catalytic function of one or more of these three essential residues. Moreover, the ligands and coordination geometry are expected to differ for Sm2+ and Pb2+ compared with Mg2+.

Accordingly, a structure of DNA-free APE1 with the preferred Mg2+ ion is needed to understand the catalytic role of this essential cofactor for APE1 and related DNase I-like enzymes. This notion is underscored by continuing controversy as to whether the DNase I superfamily enzymes require one or two Mg2+ (or Ca2+) ions for catalysis (Gao et al., 2012 ▶; Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶; Jones et al., 1996 ▶; Parsiegla et al., 2012 ▶) and the proposal that a single Mg2+ cofactor moves from the A site in the free enzyme to the B site in the enzyme–substrate (ES) complex during catalysis (Oezguen et al., 2007 ▶, 2011 ▶). Here, we report the crystal structure of human APE1 solved at 1.92 Å resolution with a single Mg2+ ion bound in the active site. This new structure, together with the recently reported structure of an enzyme–product (EP) complex of APE1, which also contains a single active-site Mg2+ (Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶), informs on the mechanism of this critical repair enzyme.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Protein preparation and crystallization

Human APE1 lacking the 38 N-terminal residues, APE1ΔN38, was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified (at 4°C) as described previously (Manvilla et al., 2009 ▶). The sample used for crystallization consisted of APE1ΔN38 (∼9 mg ml−1) in a neutral-pH buffer consisting of 0.01 M HEPES pH 7.5, 0.025 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM MgCl2. Crystals were grown by vapor diffusion at 22°C in sitting-drop format using 0.5 µl protein sample and 1.5 µl mother liquor, which consisted of 0.1 M MES pH 6.5, 30%(v/v) PEG 300. Crystals were grown for 3–5 d, the mother liquor was supplemented with 20% glycerol and the crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen.

2.2. Data collection, structure determination and refinement

X-ray diffraction data were collected on beamline 7-1 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL). The images were processed and scaled using MOSFLM (Leslie & Powell, 2007 ▶) and AIMLESS (Evans, 2011 ▶) from the CCP4 program suite (Winn et al., 2011 ▶). Initial phases were obtained by molecular replacement using the program Phaser (McCoy et al., 2005 ▶) with a previously determined crystal structure of APE1 (PDB entry 1bix; Gorman et al., 1997 ▶) as the search model. Model building was performed with Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶) and model refinement was performed using REFMAC (Winn et al., 2001 ▶). The final coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank as entry 4lnd. Structural figures were prepared with PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Overall structure of the APE1 holoenzyme

A construct of human APE1 that lacks the 38 N-terminal residues, APE1ΔN38 (Manvilla et al., 2009 ▶), was crystallized under neutral pH conditions by sitting-drop vapor diffusion (at 22°C). The crystals belonged to the monoclinic space group C2, with three molecules per asymmetric unit (Table 1 ▶). The structure was solved by molecular replacement and refined to a crystallographic R factor of 21.7% and an R free of 24.1% at a resolution of 1.92 Å (Table 1 ▶), and includes all but the 43 N-terminal residues of human APE1. We note that the 40–43 N-terminal residues have been absent in all crystal structures determined to date for APE1, either free or DNA-bound, even when the full-length enzyme was used for crystallization (Beernink et al., 2001 ▶). This is consistent with our findings from NMR studies that these residues are disordered in solution (Manvilla et al., 2009 ▶, 2011 ▶). Previous studies indicated that the 40 N-terminal residues are dispensable for the repair and the redox activities of APE1 (Izumi & Mitra, 1998 ▶).

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics for APE1ΔN38 .

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data collection | |

| Space group | C2 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 165.8, b = 90.9, c = 94.0, α = 90.0, β = 123.2, γ = 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 48.0–1.92 (1.96–1.92) |

| R p.i.m. | 0.069 (0.482) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 3.6 (0.7) |

| CC1/2 | 0.991 (0.745) |

| Completeness (%) | 85.4 (84.4) |

| Multiplicity | 2.5 (2.4) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 25.1 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 48.0–1.92 |

| No. of reflections | 71263 |

| R work/R free (%) | 21.7/24.1 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Total | 6443 |

| Protein | 6320 |

| Waters | 120 |

| Metal ions | 3 |

| B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 34.7 |

| Waters | 32.5 |

| Metal ions | 35.0 |

| Ramachandran plot† (%) | |

| Favored regions | 90.1 |

| Allowed regions | 9.8 |

| Generously allowed regions | 0.1 |

| Outliers | 0.0 |

| R.m.s.d. | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.243 |

The Ramachandran analysis was performed using PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993 ▶).

The structure presented here is similar in overall fold to the previously reported structures of DNA-free APE1, as expected, but there are several important differences, as summarized in Table 2 ▶. Ours is the first reported structure of the DNA-free enzyme with the essential Mg2+ cofactor bound in the active site, and it reveals the detailed mechanism and geometry for Mg2+ coordination, as discussed below. While some residues within the structured catalytic domain are absent in previously reported structures of DNA-free APE1, electron density is observed for all residues from Leu44 to the C-terminus (Leu318) in the structure reported here. When compared with the previously determined Sm3+-bound and Pb2+-bound structures, the new structure here is most similar to the structure containing a single Pb2+ ion in the active site and least similar to the structure with two Pb2+ ions (Table 2 ▶). While the single-Pb2+ structure is of relatively high resolution (1.95 Å; Beernink et al., 2001 ▶), the crystals were grown under acidic conditions (pH 4.6) and the structure lacks 17 residues in the catalytic domain of the enzyme (Table 2 ▶). For these reasons, and others detailed below, the structure reported here provides a substantial advance over the previously reported structures of DNA-free APE1.

Table 2. Comparison of data-collection and refinement statistics for APE1 structures.

| PDB entry | 1bix | 1hd7 | 1e9n | 3u8u † | 4lnd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH of crystallization | 6.2 | 4.6 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 6.5 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.20 | 1.95 | 2.20 | 2.15 | 1.92 |

| Space group | C2 | C2 | C2 | P21 | C2 |

| Molecules per asymmetric unit | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| Residues absent from structure‡ | 100–104 | 102–112, 122–127 | 124–125 | None§ | None |

| Metal(s) in active site | Sm3+ | Pb2+ | Pb2+ (2) | Mg2+ | Mg2+ |

| R.m.s.d. to new structure¶ (Å) | |||||

| Molecule A | 0.293 | 0.280 | 0.363 | 0.219–0.309 | N/A |

| Molecule B | 0.321 | 0.307 | 0.383 | 0.225–0.315 | N/A |

| Molecule C | 0.271 | 0.265 | 0.353 | 0.220–0.284 | N/A |

The structure was deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB entry 3u8u) but has not been reported in the literature.

All structures of APE1 lack the N-terminal residues up to residue ∼40.

Some residues (123–128) are missing in two of the six molecules in the asymmetric unit.

R.m.s.d. determined from pairwise alignment (all atoms) using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶). Values are given for each of the three molecules in the asymmetric unit for the new structure reported here (PDB entry 4lnd). For PDB entry 1e9n the values shown for molecule A are nearly identical (±0.5%) to those for molecule B. For PDB entry 3u8u the range of r.m.s.d. values is given for aligning each of the three molecules in the asymmetric unit of our structure (PDB entry 4lnd) with each of the six protein molecules in the asymmetric unit of PDB entry 3u8u.

3.2. Octahedral coordination of the single Mg2+ ion

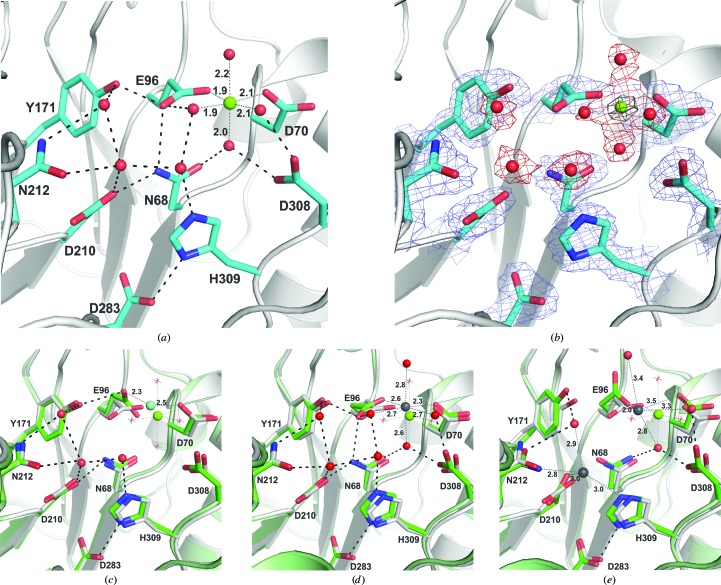

As shown in Fig. 1 ▶(a), the new APE1 structure reveals a single Mg2+ ion in the active site, coordinated in ideal octahedral geometry by two carboxylate groups (Asp70 and Glu96) and four water molecules. Fig. 1 ▶(a) also shows six additional active-site groups that are strictly conserved in the DNase I superfamily (Tyr171 is replaced by His in some cases) and three additional water molecules that are bound by these residues. Fig. 1 ▶(b) shows the same view with an F o − F c OMIT map contoured at 8.0σ for the Mg2+ ion and a 2F o − F c OMIT map contoured at 1.5σ for the side chains and water molecules. The same octahedral metal-coordination geometry and ligands are observed in all three active sites of the asymmetric unit. The Mg2+-coordination distances for each of the three sites in the asymmetric unit are provided in Table 3 ▶; they are in good agreement with the Mg2+-coordination distances in high-resolution (≤1.25 Å) protein crystal structures and compounds in the Cambridge Structural Database (2.07 ± 0.05 Å for water as a ligand, 2.07 ± 0.10 Å for a carboxylate ligand; Harding, 2006 ▶). The binding site for Mg2+ in the new structure is the same as that observed for the surrogate metals Sm3+ and Pb2+ in previous structures of DNA-free APE1 (Figs. 1 ▶ c, 1 ▶ d and 1 ▶ e) and this site is typically referred to as the ‘A site’. However, important differences are observed regarding the mechanism and geometry of metal coordination, as discussed below.

Figure 1.

New crystal structure of human APE1 with the native Mg2+ cofactor and previous structures with surrogate metals. (a) Close-up view of the active site of the new structure, showing Mg2+ and several ordered water molecules (molecule A of the three molecules in the asymmetric unit for PDB entry 4lnd). Also shown are the important catalytic residues; all but Asp70 are strictly conserved in the DNase I superfamily (Tyr171 is replaced by His in some members). The octahedral coordination of Mg2+ is indicated by dotted lines with distances provided (also given in Table 3 ▶). Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. (b) The same view of the active site showing a 2F o − F c OMIT map contoured at 1.5σ for protein and waters and an F o − F c OMIT map contoured at 8.0σ for the Mg2+ ion (black mesh). Note that one or more of the three non-Mg2+-coordinating water molecules are not observed in the other two protein molecules (B and C) in the asymmetric unit. (c) Previously reported structure of Sm3+-bound APE1 (green; PDB entry 1bix; Gorman et al., 1997 ▶) aligned with the new Mg2+-bound structure (white). The coordination of the Sm3+ ion (cyan) is shown (dotted lines) with distances. The coordination of Mg2+ (green) in the new structure is also indicated (without distances). Water molecules shown as red spheres and hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) are for the Sm3+-bound structure. The water molecules that coordinate Mg2+ are shown as red stars. (d) The previously reported structure of APE1 with one Pb2+ ion (green; PDB entry 1hd7; Beernink et al., 2001 ▶) aligned with the new Mg2+-bound structure (white). The coordination of the Pb2+ ion (gray) is shown (dotted lines) with distances and the coordination of Mg2+ (green) is also indicated. Water molecules (red spheres) and hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) are for the Pb2+-bound structure (waters that coordinate Mg2+ are shown as red stars). (e) The previously reported structure of APE1 with two Pb2+ ions (green; PDB entry 1e9n; Beernink et al., 2001 ▶) aligned with the new Mg2+-bound structure (white). The coordination of the Pb2+ ions (gray) is shown (dotted lines) with distances and the coordination of Mg2+ (green) is similarly indicated. Water molecules (red spheres) and hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) are for the Pb2+-bound structure (waters that coordinate Mg2+ are shown as red stars).

Table 3. Mg2+-coordination distances (Å) for each molecule of the asymmetric unit.

Interatomic distances (Å) between the Mg2+ ion and the six coordinating ligands (Fig. 1 ▶ a). Three of the four coordinating water molecules are denoted by the residue(s) to which they are bound (in parentheses). The ‘upper’ H2O refers to the uppermost H2O ligand in Fig. 1 ▶.

| Molecule | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | A | B | C |

| H2O (upper) | 2.20 | 2.08 | 2.14 |

| H2O (Glu96) | 1.94 | 2.07 | 2.03 |

| H2O (308) | 2.07 | 2.10 | 2.12 |

| Asp70 | 2.14 | 2.04 | 1.94 |

| Glu96 | 1.95 | 1.98 | 1.92 |

| H2O (Asn68, Glu308) | 2.00 | 2.16 | 2.11 |

We find no evidence for a second Mg2+ ion at the ‘B site’, which was observed to bind a second Pb2+ ion via direct coordination through the side chains of Asp210, Asn212 and His309 in a previous APE1 structure (Fig. 1 ▶ e; Beernink et al., 2001 ▶). Rather, a water molecule occupies this site in the structure described here, forming hydrogen bonds to the side chains of Asp210 and Asn212 and two other active-site water molecules (Fig. 1 ▶ a); the contact distances (≥2.6 Å) and geometry indicate that it is not a second Mg2+ ion. The observation that DNA-free APE1 binds a single Mg2+ ion at the A site (Asp70 and Glu96) and that a second Mg2+ ion does not bind at the B site is consistent with the results of two previous NMR studies (Lowry et al., 2003 ▶; Lipton et al., 2008 ▶). While it is possible that a second Mg2+ ion could enter the B site with the DNA substrate, this seems unlikely given that a second Mg2+ ion is not observed in either of the two existing structures of the APE1 enzyme–product complex (Mol et al., 2000 ▶; Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶).

One of the two residues that directly coordinate the Mg2+ ion, Glu96, is strictly conserved in the DNase I superfamily, while the other, Asp70, seems to be restricted to mammalian APE1 (Gorman et al., 1997 ▶; Castillo-Acosta et al., 2009 ▶). We note that Glu96 also directly coordinates the single Mg2+ ion that was observed in a recently reported enzyme–product (EP) complex of APE1, while the Asp70 carboxylate binds a water molecule that in turn coordinates Mg2+ (Fig. 2 ▶ a; Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶). Previous studies found that the E96Q mutation causes a 2300-fold loss in AP endonuclease activity (Erzberger & Wilson, 1999 ▶), consistent with an important role of Glu96 in coordinating the Mg2+ cofactor. An important role of Asp70 is indicated by the 26-fold loss in endonuclease activity of the D70A or D70R mutations (Erzberger & Wilson, 1999 ▶). Moreover, D70A and E96Q variants exhibit diminished endonuclease activity relative to native APE1 under conditions of limiting Mg2+ (Nguyen et al., 2000 ▶; Castillo-Acosta et al., 2009 ▶).

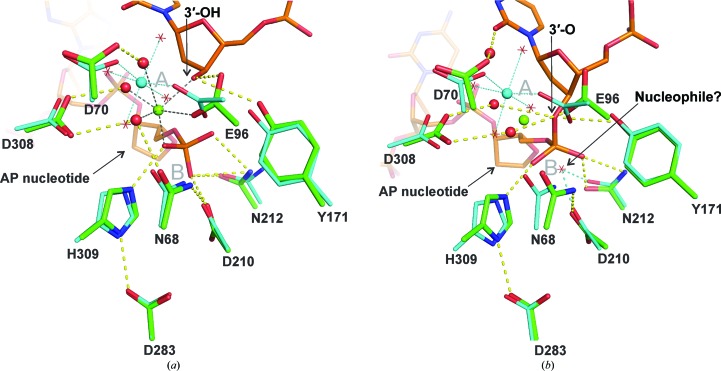

Figure 2.

Alignment of the new Mg2+-bound APE1 structure with DNA-bound structures. (a) Recently determined structure of the APE1 enzyme–product (EP) complex (green; PDB entry 4iem; Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶) aligned with the structure of Mg2+-bound APE1 (cyan) reported here. DNA from the EP complex (orange) contains a 3′-OH and a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP). The Mg2+ ion from the EP complex is colored green and its coordination is indicated by black dotted lines. The Mg2+ ion from the new DNA-free structure is colored cyan and its coordination is indicated by cyan dotted lines, with coordinating water molecules shown as red stars. Hydrogen-bond interactions (yellow dashes) are shown for the EP complex only. The approximate locations of the A and B sites are noted (gray symbols). (b) Structure of the APE1 enzyme–substrate (ES) complex (green; PDB entry 1dew; Mol et al., 2000 ▶) aligned with the new structure of Mg2+-bound APE1 (cyan). The DNA in the ES complex (orange) contains an intact abasic site and Mg2+ was omitted from the ES complex to halt P—O bond cleavage. The green sphere indicates the position of the Mg2+ ion in the EP complex (also aligned with DNA-free APE1). Mg2+ in the DNA-free structure is shown in cyan; its coordination is indicated by cyan dotted lines, with coordinating waters shown as red stars. Hydrogen-bond interactions (yellow dashes) are shown for the ES complex. The potential nucleophilic water from our DNA-free structure is shown as a red star, with cyan dashes indicating hydrogen bonds to Asp210 and Asn212. This water molecule was also observed in previous structures of APE1 with Sm3+ or a single Pb2+ ion (Fig. 1 ▶). The approximate locations of the A and B sites are noted (gray symbols).

In addition to the two carboxylate groups, the Mg2+ cofactor is coordinated by four water molecules, three of which are bound by the side chains of Asn68, Glu96 and Asp308 (Fig. 1 ▶ a). All of these residues are strictly conserved in the DNase I superfamily and, as noted above, Glu96 also coordinates Mg2+ directly. The catalytic importance of Asn68 is indicated by the 600-fold loss in AP endonuclease activity caused by the N68A mutation (Nguyen et al., 2000 ▶). In addition to coordinating Mg2+ (indirectly) in the free enzyme and in the EP complex (Fig. 2 ▶ a), Asn68 contacts the essential carboxylate group of Asp210 and could potentially facilitate its role in catalysis (Fig. 1 ▶ a). The carboxylate of Asp308 binds two of the four inner-sphere water molecules of Mg2+. While the D308A variant exhibits a relatively modest fivefold loss in AP endonuclease activity, it has a much greater sensitivity to low Mg2+ conditions than does native APE1 (Erzberger & Wilson, 1999 ▶; Nguyen et al., 2000 ▶).

The coordination mechanism for Mg2+ observed in the new structure differs substantially from that observed for Sm3+ and Pb2+ in previous structures of DNA-free APE1. While the APE1 structure with Sm3+ suggested that Asp70 and Glu96 could directly coordinate the Mg2+ ion (Gorman et al., 1997 ▶), the four water molecules that coordinate Mg2+ in the new structure are not found in the Sm3+-bound structure (Fig. 1 ▶ c). Another structure, determined under acidic conditions (pH 4.6), contains a single Pb2+ ion that exhibits octahedral coordination involving Asp70, Glu96 and four water molecules (Fig. 1 ▶ d; Beernink et al., 2001 ▶), similar to the coordination of Mg2+ found in the structure reported here. However, the metal–oxygen distances are substantially longer for Pb2+ relative to Mg2+ (Figs. 1 ▶ a and 1 ▶ d). A third structure, determined at pH 7.5, contained two Pb2+ ions, one at the A site and the other at the B site, coordinated by Asp210, Asn212 and His309 (Fig. 1 ▶ e). As such, the second Pb2+ ion displaces the water molecule that is bound by Asp210 and Asn212 in all of the single-metal structures of DNA-free APE1 (Figs. 1 ▶ a, 1 ▶ c and 1 ▶ d). As discussed below, this water molecule seems to be a good candidate for the nucleophile in the hydrolytic reaction catalyzed by APE1. Again, we observe no evidence for Mg2+ at the B site in the structure reported here, consistent with findings that imidazole side chains are not a common ligand for Mg2+ ions (Harding, 2001 ▶, 2006 ▶). The coordination geometry for Pb2+ in the A site of the two-Pb2+ structure (Fig. 1 ▶ e) is non-ideal when compared with the octahedral geometry observed in structures with a single Pb2+ ion (Fig. 1 ▶ d) or a single Mg2+ ion (Fig. 1 ▶ a). Thus, our structure, together with previous structures, suggests that Pb2+ inhibits APE1 by binding to this B site and perturbing the function of one or more of the three essential catalytic residues (Asp210, Asn212 or His309) and/or by perturbing binding of Mg2+ at the A site.

3.3. Coordination of Mg2+ in the free enzyme and the enzyme–product complex

The structure of Mg2+-bound APE1 reported here, together with the recently determined structure of an enzyme–product (EP) complex (2.4 Å resolution; Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶), allows a detailed comparison of the position and coordination mechanism for the essential Mg2+ cofactor at two steps along the catalytic pathway. Shown in Fig. 2 ▶(a) is an alignment of these structures, with active-site residues colored cyan for DNA-free APE1 and green for the EP complex and with DNA colored orange. For the EP complex, the enzyme active site contains a single Mg2+ ion (green sphere) and DNA with a hydrolyzed phosphodiester bond, i.e. 3′-OH and 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP). The conserved catalytic residues are positioned nearly identically in the aligned structures, except for Glu96, which repositions between the free enzyme and EP complex, predominantly via rotation about χ1, with little change in the main chain. Notably, the conformation of Glu96 observed in the EP (and ES) complex is similar to that observed in the structure of DNA-free APE1 with two Pb2+ ions (Fig. 1 ▶ e) and in some of the six molecules in the asymmetric unit of the unpublished structure of Mg2+-bound APE1 (not shown). Although the orientation of Glu96 is the same for all three active sites in the asymmetric unit for our Mg2+-bound structure (Fig. 1 ▶ a), these observations suggest the possibility of conformational sampling for Glu96 in the DNA-free enzyme. The Mg2+ ion is positioned relatively similarly in the DNA-free enzyme (cyan sphere) and the EP complex (green sphere), with a separation of 2.2 Å, suggesting that the cofactor could exhibit minimal movement during catalysis. As discussed above, we find that DNA-free APE1 coordinates Mg2+ via the carboxylate groups of Asp70 and Glu96 and four water molecules. In the EP complex, Mg2+ is coordinated directly by Glu96 (carboxylate), the 3′-OH (leaving group), a nonbridging O atom of the nascent 5′-phosphate and by three water molecules, one of which is bound to Asp70 (Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶). Thus, one carboxylate O atom of Glu96 contacts Mg2+ in both the free enzyme and the EP complex, while the other carboxylate O atom of Glu96 trades a contact with water in the free enzyme for a contact with the 3′-OH in the EP complex (Fig. 2 ▶ a). These observations suggest that Mg2+ might not need to move far from its location in the free enzyme to perform its catalytically essential function(s), which could include positioning of the target phosphate, polarization of the scissile P—O bond and stabilization of the negative charge developing at one of the nonbridging O atoms and/or the 3′-oxygen in the transition state (Gorman et al., 1997 ▶; Mol et al., 2000 ▶; Herschlag et al., 1991 ▶).

3.4. Alignment of the Mg2+-bound enzyme with the enzyme–substrate complex

It is also informative to compare the new structure of Mg2+-bound APE1 with a previously reported structure of the enzyme–substrate (ES) complex, which was crystallized in the absence of Mg2+ in order to preclude hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond (Mol et al., 2000 ▶). Shown in Fig. 2 ▶(b) is an alignment of these structures, with active-site residues colored cyan for the free enzyme and green for the ES complex and with DNA colored orange. In the ES complex, the DNA backbone is intact and the abasic nucleotide is flipped into the active site. For reference, the Mg2+ ion from the EP complex (Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶) is shown as a green sphere and seems to be well positioned with respect to the substrate DNA to perform one or more of the catalytic functions mentioned above. Previous solid-state 25Mg NMR studies found two distinct environments for a single Mg2+ ion in the ES complex, suggesting that the cofactor is disordered (Lipton et al., 2008 ▶). This could reflect conformational exchange of the Mg2+ ion in the ES complex, perhaps between its location in the free enzyme and a site similar to that observed in the EP complex (Fig. 2 ▶ b).

Although no candidate nucleophile is observed in the crystal structure of the ES complex (Mol et al., 2000 ▶), a water molecule coordinated by Asp210 and Asn212 in the DNA-free structure reported here seems to be well positioned to serve as the nucleophile for hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond (Figs. 1 ▶ a and 2 ▶ b). The idea that the nucleophile may be bound by Asp210 and Asn212 and activated by Asp210 is supported by recent molecular-dynamics studies (Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶). The Asp210/Asn212-bound water molecule was observed in previously determined structures of DNA-free APE1, except the structure with two Pb2+ ions, where the potential nucleophile is displaced by the second Pb2+ ion (Figs. 1 ▶ c, 1 ▶ d and 1 ▶ e; Beernink et al., 2001 ▶). As noted, binding of Pb2+ to the B site could account for the finding that Pb2+ is a potent inhibitor of APE1. Our structure also indicates that a water molecule binds to the imidazole of His309 (in one of the three active sites in the asymmetric unit), and the same water is observed in the DNA-free structures with Sm3+ or a single Pb2+ ion (Fig. 1 ▶) and in the unpublished Mg2+ structure (in four of the six molecules in the asymmetric unit; not shown). This is notable because it has been proposed that His309 acts as a general base to activate the water nucleophile in reactions catalyzed by APE1 and related enzymes (Gorman et al., 1997 ▶; Mol et al., 1995 ▶; Lipton et al., 2008 ▶; Suck & Oefner, 1986 ▶). However, the His309-bound water seems to be poorly positioned for nucleophilic attack in the aligned structures (free E and ES complex) when compared with the Asp210-bound water (Fig. 2 ▶ b), and His309 seems to be poorly positioned to act as the essential general base. For this and other reasons, we favor the hypothesis that Asp210 activates the nucleophile (Tsutakawa et al., 2013 ▶; Mol et al., 2000 ▶). Nevertheless, the observation that the Asp210-bound and His309-bound waters are not seen in all three active sites of the asymmetric unit in the new structure suggests that this network of active-site water molecules is dynamic and that the position of these water molecules in the DNA-free enzyme will likely change upon formation of the ES complex. Additional studies are needed to establish the mechanism of nucleophile activation for APE1 and other members of the DNase I superfamily.

The crystal structure with two Pb2+ ions raised the possibility that a second Mg2+ ion binds to the B site (Asp210, Asn212 and His309) in the ES complex, where it might stabilize a hydroxide ion for nucleophilic attack (Beernink et al., 2001 ▶). However, removal of the D210A and Asn212 side chains by mutagenesis leads to huge (104–105-fold) losses in steady-state AP endonuclease activity (i.e. k cat; Erzberger & Wilson, 1999 ▶; Rothwell & Hickson, 1996 ▶; Rothwell et al., 2000 ▶). As noted previously, the mutational effect on k cat is likely to underestimate the effect on the chemical step; k cat is strongly limited by a step after the chemistry for wild-type APE1, while it is likely to report on the chemical step for severely impaired mutants (Maher & Bloom, 2007 ▶). Indeed, single-turnover experiments suggest that the D210A mutation slows the chemical step by up to 108-fold (Maher & Bloom, 2007 ▶). The observation of such severe damaging effects seems more consistent with a direct role for Asp210 and Asn212 in binding and activating the nucleophile rather than coordinating a catalytic Mg2+ ion. As noted above, our structure (1.9 Å resolution) and previously determined structures of free APE1 (except for the two-Pb2+ structure) contain a water molecule at the ‘B’ site of the DNA-free enzyme and a second Mg2+ is not observed in the recently determined structure of the EP complex (2.4 Å resolution). Together, these observations argue against the idea that Mg2+ binds to both the A and B sites or that a single Mg2+ moves from the A site in the free enzyme to the B site in the ES complex to activate the water nucleophile and then back to the A site in the EP complex (Oezguen et al., 2007 ▶, 2011 ▶).

4. Concluding remarks

The structure presented here is of the highest resolution reported for human APE1 to date, was solved at neutral pH, includes all residues in the catalytic domain and reveals the detailed mechanism for octahedral coordination of the essential Mg2+ cofactor. The results provide new insight into the role of divalent metal-ion cofactors in the large and diverse DNase I superfamily of enzymes that catalyze phosphoryl-transfer reactions. This new structure, and the approach employed to obtain high-resolution structures with the native Mg2+ cofactor, could be useful for the design and optimization of inhibitors of APE1, an essential repair enzyme that is an important target for novel anticancer agents and adjuvants to existing agents (Adhikari et al., 2008 ▶; Abbotts & Madhusudan, 2010 ▶).

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: APE1, 4lnd

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM72711 (to ACD) and by the American Cancer Society (RSG-09-058-01-GMC to EAT). BAM was supported by a Chemistry–Biology Interface (CBI) Training grant from the NIH (T32-GM066706). Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the US Department of Energy Office of Science by Stanford University. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393) and the National Center for Research Resources (P41RR001209). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS, NCRR or NIH.

References

- Abbotts, R. & Madhusudan, S. (2010). Cancer Treat. Rev. 36, 425–435. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, S., Choudhury, S., Mitra, P. S., Dubash, J. J., Sajankila, S. P. & Roy, R. (2008). Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 8, 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Barzilay, G., Mol, C. D., Robson, C. N., Walker, L. J., Cunningham, R. P., Tainer, J. A. & Hickson, I. D. (1995). Nature Struct. Biol. 2, 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beernink, P. T., Segelke, B. W., Hadi, M. Z., Erzberger, J. P., Wilson, D. M. III & Rupp, B. (2001). J. Mol. Biol. 307, 1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bhakat, K. K., Mantha, A. K. & Mitra, S. (2009). Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 621–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Acosta, V. M., Ruiz-Pérez, L. M., Yang, W., González-Pacanowska, D. & Vidal, A. E. (2009). Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1829–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, M. A., Dedon, P. C., Wilson, D. M. III, Demple, B. & Weinfeld, M. (1999). Biochem. Pharmacol. 57, 531–538. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen, D. S., Herman, T. & Demple, B. (1991). Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 5907–5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen, J. & Stubbe, J. (2005). Nature Rev. Cancer, 5, 102–112. [DOI] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. L. (2002). PyMOL http://www.pymol.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Demple, B. & Harrison, L. (1994). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63, 915–948. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Demple, B., Herman, T. & Chen, D. S. (1991). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 11450–11454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dlakić, M. (2000). Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 272–273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Erzberger, J. P. & Wilson, D. M. III (1999). J. Mol. Biol. 290, 447–457. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. R. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 282–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fung, H. & Demple, B. (2005). Mol. Cell, 17, 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fung, H. & Demple, B. (2010). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 4968–4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gao, R., Huang, S.-Y. N., Marchand, C. & Pommier, Y. (2012). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30842–30852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gorman, M. A., Morera, S., Rothwell, D. G., de La Fortelle, E., Mol, C. D., Tainer, J. A., Hickson, I. D. & Freemont, P. S. (1997). EMBO J. 16, 6548–6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harding, M. M. (2001). Acta Cryst. D57, 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harding, M. M. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 678–682. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Herschlag, D., Piccirilli, J. A. & Cech, T. R. (1991). Biochemistry, 30, 4844–4854. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Izumi, T., Brown, D. B., Naidu, C. V., Bhakat, K. K., Macinnes, M. A., Saito, H., Chen, D. J. & Mitra, S. (2005). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 5739–5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Izumi, T., Hazra, T. K., Boldogh, I., Tomkinson, A. E., Park, M. S., Ikeda, S. & Mitra, S. (2000). Carcinogenesis, 21, 1329–1334. [PubMed]

- Izumi, T. & Mitra, S. (1998). Carcinogenesis, 19, 525–527. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jones, S. J., Worrall, A. F. & Connolly, B. A. (1996). J. Mol. Biol. 264, 1154–1163. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kane, C. M. & Linn, S. (1981). J. Biol. Chem. 256, 3405–3414. [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993). J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291.

- Leslie, A. G. W. & Powell, H. R. (2007). Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography, edited by R. J. Read & J. L. Sussman, pp. 41–51. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Lindahl, T. (1993). Nature (London), 362, 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lipton, A. S., Heck, R. W., Primak, S., McNeill, D. R., Wilson, D. M. & Ellis, P. D. (2008). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9332–9341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Loeb, L. A. (1985). Cell, 40, 483–484. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lowry, D. F., Hoyt, D. W., Khazi, F. A., Bagu, J., Lindsey, A. G. & Wilson, D. M. III (2003). J. Mol. Biol. 329, 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maher, R. L. & Bloom, L. B. (2007). J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30577–30585. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Manvilla, B. A., Varney, K. M. & Drohat, A. C. (2009). Biomol. NMR Assign. 4, 5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Manvilla, B. A., Wauchope, O., Seley-Radtke, K. L. & Drohat, A. C. (2011). Biochemistry, 50, 10540–10549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2005). Acta Cryst. D61, 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McNeill, D. R., Narayana, A., Wong, H.-K. & Wilson, D. M. III (2004). Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McNeill, D. R., Wong, H.-K., Narayana, A. & Wilson, D. M. III (2007). Mol. Carcinog. 46, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mol, C. D., Izumi, T., Mitra, S. & Tainer, J. A. (2000). Nature (London), 403, 451–456. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mol, C. D., Kuo, C.-F., Thayer, M. M., Cunningham, R. P. & Tainer, J. A. (1995). Nature (London), 374, 381–386. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L. H., Barsky, D., Erzberger, J. P. & Wilson, D. M. III (2000). J. Mol. Biol. 298, 447–459. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oezguen, N., Mantha, A. K., Izumi, T., Schein, C. H., Mitra, S. & Braun, W. (2011). Bioinformation, 7, 184–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oezguen, N., Schein, C. H., Peddi, S. R., Power, E. D., Izumi, T. & Braun, W. (2007). Proteins, 68, 313–323. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parsiegla, G., Noguere, C., Santell, L., Lazarus, R. A. & Bourne, Y. (2012). Biochemistry, 51, 10250–10258. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parsons, J. L., Dianova, I. I. & Dianov, G. L. (2004). Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 3531–3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Radzicka, A. & Wolfenden, R. (1995). Science, 267, 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Robson, C. N. & Hickson, I. D. (1991). Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 5519–5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rothwell, D. G., Hang, B., Gorman, M. A., Freemont, P. S., Singer, B. & Hickson, I. D. (2000). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 2207–2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rothwell, D. G. & Hickson, I. D. (1996). Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 4217–4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Suck, D. & Oefner, C. (1986). Nature (London), 321, 620–625. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tsutakawa, S. E. et al. (2013). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8445–8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

- Winn, M. D., Isupov, M. N. & Murshudov, G. N. (2001). Acta Cryst. D57, 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xanthoudakis, S., Smeyne, R. J., Wallace, J. D. & Curran, T. (1996). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 8919–8923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yannone, S. M., Hartung, S., Menon, A. L., Adams, M. W. W. & Tainer, J. A. (2012). Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23, 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: APE1, 4lnd