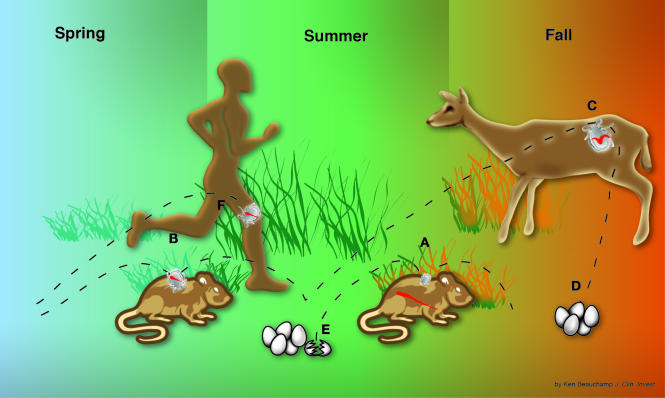

Figure 2.

The enzootic cycle of B. burgdorferi infection in the northeastern US and intersection with human Lyme disease. I. scapularis ticks feed once during each of the three stages of their usual 2-year life cycle. Typically, larval ticks take one blood meal in the late summer (A), nymphs feed during the following late spring and early summer (B), and adults feed during the fall (C), after which the female tick lays eggs (D) that hatch the next summer (E). It is critical that the tick feeds on the same host species in both of its immature stages (larval and nymphal), because the life cycle of the spirochete (wavy red line) depends on horizontal transmission: in the early summer, from infected nymphs to certain rodents, particularly mice or chipmunks (B); and in the late summer, from infected rodents to larvae (A), which then molt to become infected nymphs that begin the cycle again in the following year. Therefore, B. burgdorferi spends much of its natural cycle in a dormant state in the midgut of the tick. During the summer months, after transmission to rodents, the spirochete must evade the immune response long enough to be transferred to feeding larval ticks. Although the tick may attach to humans at all three stages, it is primarily the tiny nymphal tick (∼1 mm) that transmits the infection (F). This stage of the tick life cycle has a peak period of questing in the weeks surrounding the summer solstice. Humans are an incidental host and are not involved at all in the life cycle of the spirochete.