Abstract

Hop-derived products may contain xanthohumol (XN), isoxanthohumol (IX), and the potent phytoestrogen 8-prenylnaringenin (8-PN). To evaluate the potential health effects of these prenylflavonoids on breast tissue, their concentration, nature of metabolites, and biodistribution were assessed and compared to 17β-estradiol (E2) exposure. In this dietary intervention study, women were randomly allocated to hop (n=11; 2.04 mg XN, 1.20 mg IX, and 0.1 mg 8-PN per supplement) or control (n=10). After a run-in of ≥4d, 3 supplements were taken daily during 5d preceding an aesthetic breast reduction. Blood and breast biopsies were analyzed using HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Upon hop administration, XN and IX concentrations ranged between 0.72–17.65 nmol/L and 3.30–31.50 nmol/L, and between 0.26– 5.14 pmol/g and 1.16–83.67 pmol/g in hydrolyzed serum and breast tissue, respectively. 8-PN however, was only detected in samples of moderate and strong 8-PN producers (0.43–7.06 nmol/L and 0.78–4.83 pmol/g). Phase I metabolism appeared to be minor (~10%), whereas extensive glucuronidation was observed (>90%). Total prenylflavonoids showed a breast adipose/glandular tissue distribution of 38/62 and their derived E2-equivalents were negligible compared to E2 in adipose (384.6±118.8 fmol/g, P=0.009) and glandular (241.6±93.1 fmol/g, P<0.001) tissue, respectively. Consequently, low doses of prenylflavonoids are unlikely to elicit estrogenic responses in breast tissue.

Keywords: 17β-estradiol, 8-prenylnaringenin, bioavailability, breast tissue, Humulus lupulus

1. Introduction

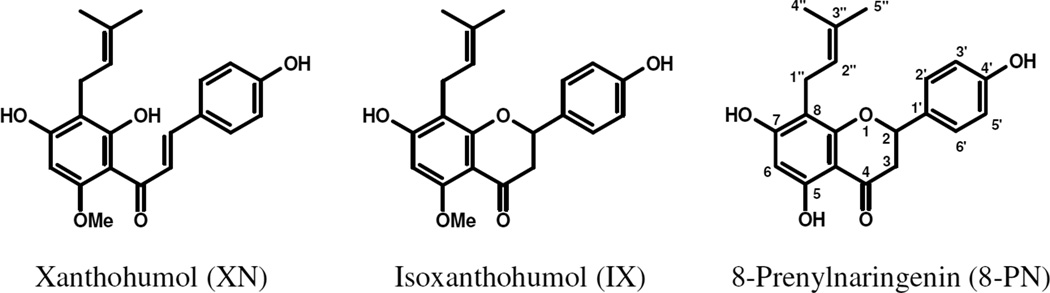

It is increasingly recognized that some non-nutrients possess biological activities that may be relevant to human health. Whether dietary exposure to such compounds may result in beneficial or adverse effects is, however, often unclear because different phytochemicals, and even mixtures thereof, are involved that affect diverse targets and act through several molecular mechanisms [1]. In particular, dietary exposure to phytoestrogens, a group of non-nutrients capable of interfering with the endogenous estrogen signaling and associated processes in vitro and/or in vivo, causes a lot of controversy and safety concerns [2–5]. As estrogens are implicated in the etiology of breast cancer, these hormonally active compounds are being evaluated as potential cancer chemopreventive or promoting agents [6,7]. In contrast to the rigorously studied soy phytoestrogens genistein and daidzein, comparatively less is known about the prenylflavonoids xanthohumol (XN), isoxanthohumol (IX), and 8-prenylnaringenin (8-PN) found in hops (Humulus lupulus L.) and hop-derived products such as beers [8] and food supplements [9,10] (Fig. 1). Whereas XN and IX possess no or weak estrogenic activity, 8-PN is one of the most potent dietary phytoestrogens [11] and unique with respect to its estrogen receptor (ER) specificity, as it binds preferentially to ERα [12]. In addition, IX, which usually predominates over 8-PN by over 10-fold [8], functions as a precursor to 8-PN as it can be O-demethylated by cytochrome P450 enzymes [13,14] and/or by intestinal microbiota [15,16]. The extent of this bioactivation varies considerably among individuals, which can be classified into weak, moderate, and strong 8-PN producers [15]. Therefore, the estrogenic potency and potential health effects of hop-derived products do not only depend on the ingested amount of 8-PN, but also on the IX concentration and the 8-PN producer phenotype [15].

FIGURE 1.

Structures of the most important prenylflavonoids found in hop-derived products: XN, IX, and 8-PN.

To properly evaluate the impact of prenylflavonoid exposure on breast carcinogenesis, more information on their bioavailability, especially their absorption, metabolism, and distribution in human breast tissue, is needed. As phase I and II reactions alter the pharmacological profiles of phytoestrogens [17,18] and as cell-type specific responses to estrogen exposure have been reported [19], not only the concentration, but also the nature of the metabolites and the biodistribution (either adipose or glandular tissue) of orally administered prenylflavonoids in breast tissue were assessed and compared to the endogenous 17β-estradiol (E2) exposure. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first controlled human study addressing these issues.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

The isolation of XN, IX, and 8-PN from spent hops was performed as described by Stevens et al. [20]. Standards of 8-(4’’-hydroxyisopentenyl)-5-methoxy-7,4’-dihydroxyflavanone (IX alcohol) and 8-(4’’-hydroxyisopentenyl)-naringenin (8-PN alcohol) were synthesized as described by Nikolic et al. [21]. Glucuronides of XN, IX, and 8-PN were prepared by incubation of aglycones with pooled human liver microsomes from 50 donors (0.374 nmol cytochrome P450/mg total protein; In Vitro Technologies, Baltimore, MD, USA) in the presence of alamethicine and uridine diphosphate glucuronic acid [14,21]. 40 nmol/L and 4 nmol/L-solutions of a synthetic 8-PN analogue (8-isopentylnaringenin synthetized according to Roelens et al. [22]) in sodium acetate buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH= 5) were used as internal standards in the analyses of urine, serum, and breast tissue, respectively. For the hydrolysis of conjugated prenylflavonoids, a 33 g/L-solution of Type H-1 Helix pomatia extract (min. 300 U β-glucuronidase/mg and 15.3 U sulfatase/mg; Sigma-Aldrich, Bornem, Belgium) in sodium acetate buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH= 5) was prepared.

2.2 Hop-derived food supplements

One batch of commercially available hop-derived food supplements (MenoHop®, Metagenics Europe, Ostend, Belgium containing the Lifenol® extract (Naturex, Avignon, France)), was kindly provided by the manufacturer. The composition and manufacturing information have been described previously [10]. The concentrations of prenylflavonoids were measured in triplicate at study onset and closure according to Bolca et al. [15]; each capsule contained 2.04 ± 0.06 mg XN, 1.20 ± 0.04 mg IX, and 0.10 ± 0.01 mg 8-PN.

2.3 Subjects

A total of 21 generally healthy Belgian or Dutch women, scheduled for an aesthetic breast reduction, were recruited for this study. The exclusion criteria were breast cancer and antibiotic treatment within the previous month. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Ghent University Hospital (EC UZG 2005/022; initial recruitment date: February 20th 2007). The volunteers were fully informed on the aims of the study and gave their written consent.

2.4 Study design

This study was designed as a randomized dietary intervention trial with a run-in phase of at least 4 d and a supplementation phase of 5 d preceding the breast reduction. Following eligibility assessment, volunteers were randomly allocated to hop supplement (n= 11: H01–11) or control (n= 10: C01–10). All participants were counseled not to change their habitual, Western-type dietary patterns, but were asked to abstain from hop-based products during the whole experimental period. A detailed list of prenylflavonoid-containing foods (all beers, some herbal teas claiming sedative properties, and young hop shoots), dietary supplements, and homeopathic treatments, including examples and brand names, was distributed in order to guide the volunteers in this respect. Additionally, subjects were instructed to report every case of doubt or fortuitous consumption, and to provide detailed information on that eating occasion, including type and portion size.

During the supplementation phase, hop-derived supplements were taken daily with meals at breakfast, lunch, and dinner (3 capsules/d). The control group did not receive any supplementation before surgery. Compliance was evaluated by subject inquiry and urinary prenylflavonoid excretion.

After the run-in phase and before anesthesia, subjects delivered spot urine samples. During surgery, blood and breast biopsies were collected. Serum was obtained by centrifugation (10 min at 600 g, room temperature (RT)) after coagulation. Aliquots of both urine and serum samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis. The tissue samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. In addition, a general questionnaire was used to collect information on the subjects’ history of antibiotic treatments, hormonal therapies, use of any other medication, dietary habits and food supplement intakes, and anthropometric measures.

2.5 Sample preparation and analytical methods

2.5.1 Urine

After spiking with 100 µL internal standard, 500 µL urine were mixed with sodium acetate buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH= 5) (50/50, v/v), incubated with or without 15 µL β-glucuronidase/sulfatase for 18 h at 37 °C, and extracted twice with 5 mL diethyl ether. Pooled upper organic layers were evaporated to dryness at RT under a gentle stream of N2, reconstituted in 250 µL methanol/water (40/60, v/v), and stored at −20 °C prior to HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

To allow standardization of diuresis, urinary excretion of creatinine was measured in triplicate according to the conventional kinetic Jaffé method [23] as described by Bolca et al. [24]. Based on a creatinine clearance rate of 0.163 mmol/(d*kg) [25], daily urinary prenylflavonoid excretions were calculated.

2.5.2 Serum

Serum samples (200 µL), spiked with 200 µL internal standard, were mixed with sodium acetate buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH= 5) (50/50, v/v), incubated with or without 100 µL β-glucuronidase/sulfatase for 18 h at 37 °C, and extracted twice with 5 mL diethyl ether. Pooled upper organic layers were evaporated to dryness at RT under a gentle stream of N2, reconstituted in 100 µL methanol/water (40/60, v/v), and stored at −20 °C prior to HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

2.5.3 Breast tissue

Breast tissue samples were dissected into fractions containing almost exclusively either pure fat or glandular tissue, based on gross inspection. Areas of adipose tissue intimately intermixed with fibroglandular tissue were avoided and connective tissue was removed. For prenylflavonoid quantification, approximately 1.2 g adipose or glandular breast tissue, spiked with 200 µL internal standard, were homogenized in 1 mL ice-cold 200 mmol/L hydrochloric acid in methanol and 1 mL hexane with a System POLYTRON® PT2100 (Kinematica AG, Luzern, Switzerland). After centrifugation (2× 10 min at 12000 g, 4°C), the hydroalcoholic phases were evaporated to dryness at RT under a gentle stream of N2 and reconstituted in 1.6 mL sodium acetate buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH= 5). Upon incubation with or without 200 µL β-glucuronidase/sulfatase during 18 h at 37 °C, samples were extracted twice with 6 mL diethyl ether. Pooled upper organic layers were evaporated to dryness at RT under a gentle stream of N2, reconstituted in 100 µL methanol/water (40/60, v/v), and stored at −20 °C prior to HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

Endogenous estrogens were extracted as described by Chetrite et al. [26]: approximately 200 mg adipose or glandular breast tissue were homogenized in 5 mL ethanol/water (70/30, v/v) using a T10 ULTRA-TURRAX® (Ika, Werk Staufen, Germany), and, after precipitation (2× 24 h at −20 °C), extracted with 5 mL ethyl acetate/hexane (60/40, v/v). The upper organic layer was evaporated to dryness at 37 °C under a gentle stream of N2 and reconstituted in 500 µL steroid-free serum (Std0-DRG, DRG Instruments GmbH, Marburg, Germany). Samples were analyzed for E2 in triplicate using a commercial quantitative ELISA (EIA-4399, DRG Instruments GmbH, Marburg, Germany) [27]. According to the manufacturer, this kit had a sensitivity of <5.13 pmol/L serum, an intra- and interassay CV of 6.4% and 7.6%, respectively, and a cross-reactivity of 0.2% with estrone, 0.05% with estriol, and <0.05% with 17α-estradiol. A cross-reactivity of 0.5% was measured for prenylflavonoids.

2.5.4.Quantitative HPLC-MS/MS analysis of prenylflavonoid aglycones

Quantification of total, i.e., free and deconjugated, prenylflavonoids in hydrolyzed urine, serum, and tissue samples (duplicate extractions, single HPLC-MS/MS measurements) was performed by HPLC-MS/MS using a Waters 2695 Alliance separations module (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) and a triple quadrupole MS operated in negative ESI mode (TSQ Quantum, Thermo Scientific, San Jose, California, USA). Separations were carried out on an Atlantis® T3 C18 reversed-phase column (5 µm; 2.1 × 100 mm; Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) at 35 °C and using a gradient of solvent A (i.e., 8.7 mmol/L aqueous acetic acid) and solvent B (i.e., methanol) with the following elution profile: 0–8 min, from 83% to 100% B in A; 8.1–13 min, 100% B; 13.1–20 min, from 100% to 53% B in A, and a flow rate of 250 µL/min. The injection volume was 10 µL. Ionization and detection parameters were optimized during infusion experiments with standards of XN, IX, 8-PN, IX alcohol, 8-PN alcohol, and internal standard. MS/MS data were collected in selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode with specific transitions of parent and product ions for each analyte: XN and IX (m/z 353/233/119), 8-PN (m/z 339/219/119), IX alcohol (m/z 369/249/119), 8-PN alcohol (m/z 355/235/119), and internal standard (m/z 341/119). For XN, IX, and 8-PN linear (r²> 0.99) calibration curves were obtained over a range of 0.5–500 nmol/L in urine, 0.05–50 nmol/L in serum, and 0.1–100 pmol/g in tissue, with LOD (S/N= 3) and LOQ (S/N= 10) of 0.003 nmol/L and 0.010 nmol/L in urine and serum, and 0.026 pmol/g and 0.088 pmol/g in tissue, respectively.

2.5.5 Qualitative HPLC-MS/MS analysis of prenylflavonoid metabolites

Qualitative analyses of non-hydrolyzed urine, serum, and tissue samples (single extractions, single HPLC-MS/MS measurements) were performed with the equipment and conditions described above, except for the following changes. The LC mobile phase gradient was adapted: 0–30 min, from 42% to 82% B in A; 30.1–40 min, 42% B in A, with a flow rate of 220 µL/min and an injection volume of 20 µL. Ionization and detection parameters were optimized during infusion experiments with both aglycones and glucuronides of XN, IX, and 8-PN, and internal standard. MS/MS data were collected in SRM mode with specific transitions of parent and product ions for each analyte: XN and IX (m/z 353/233), 8-PN (m/z 339/219), IX alcohol (m/z 369/119), 8-PN alcohol (m/z 355/235), XN glucuronide and IX glucuronide (m/z 529/353/233), 8-PN glucuronide (m/z 515/339/219), and internal standard (m/z 341/119).

2.6 Statistical analyses

SPSS for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Results were considered statistically significant at an α two-tailed level of 0.05. Means and SEM of urine, serum, and tissue concentrations were calculated. Tests for normality and equality of the variances were performed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene’s test, respectively. Intrasubject comparisons were evaluated with the paired Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-rank test, whereas the Student’s t-test was used to compare means between groups. Using the TwoStep cluster analysis protocol, subjects were phenotyped as weak, moderate or strong 8-PN producers based on the urinary excretion of 8-PN/(8-PN+IX) [15].

3 Results

3.1 Study population

A total of 21 generally healthy women undergoing an aesthetic breast reduction participated in this study. Their age and BMI, based on self-reported weight and height measurements, ranged between 18–60 y and 19–36 kg/m², respectively, and did not differ significantly (P= 0.758 and P= 0.088) between groups. Six women (32%; H01–03 and C01–03) were in the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle and 2 (11%; H04 and C04) in the luteal phase, whereas 11 (46%; H05–10 and C05–09) were menopausal. Four women followed a therapy with exogenous estrogens: i.e., oral (5%; C03) or intra-uterine (10%; H11 and C10) contraceptives, or estrogen therapy (5%; H10); while one was treated with anti-estrogens (5%; C09). Based on their urinary excretion profiles, 3 participants (27%; H06, H09, and H10) were phenotyped as moderate 8-PN producers and 3 (27%; H02, H03, and H07) as strong 8-PN producers.

3.2 Total exposure

The exposure to XN, IX, and 8-PN upon hop supplementation was assessed as the sum of unconjugated aglycones and deconjugated (sulfo)glucuronides and sulfates as measured in hydrolyzed urine, serum, and breast adipose and glandular tissue (Table 1). None of the control samples contained detectable amounts of hop-derived phytoestrogens. The estimated daily urinary prenylflavonoid excretion profiles varied considerably between individuals and were in the nmol/d-range (4.45–52.64 nmol XN/d, 84.47–850.09 nmol IX/d, and 13.18–104.14 nmol 8-PN/d). XN and IX were found in all hydrolyzed serum samples and ranged between 0.72–17.65 nmol/L and 3.30–31.50 nmol/L, respectively. However, only good 8-PN producers (3 strong and 2 moderate) had circulating 8-PN concentrations (0.43–7.06 nmol/L) exceeding the LOQ. In breast adipose and glandular tissue, exposure levels of 0.26–5.14 pmol XN/g, 1.16–83.67 pmol IX/g, and 0.78–4.83 pmol 8-PN/g were measured. Unlike XN, IX could be quantified in all tissue samples, whereas 8-PN was detected in both adipose and glandular breast tissue of the moderate and strong 8-PN producers, but also in glandular tissue of 1 poor 8-PN producer (H11). No statistically significant correlations were observed between the serum and tissue concentrations of XN, IX, and 8-PN.

TABLE 1.

Urinary excretion, and serum and breast tissue concentrations of XN, IX, and 8-PN aglycones equivalents upon prenylflavonoid supplementation (i.e., 6.12 mg XN, 3.6 mg IX, and 0.3 mg 8-PN per d, during 5 d).

| Urine (nmol/d) | Serum (nmol/L) | Breast tissue (pmol/g) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose | Glandular | |||||||

| n | Mean ± SEM | n | Mean ± SEM | n |

Mean ± SEM |

n |

Mean ± SEM |

|

| XN | 11 | 22.52 ± 4.93 | 11 | 4.99 ± 1.79 | 9 | 0.69 ± 0.17 | 10 | 2.58 ± 0.45 |

| IX | 11 | 526.16 ± 70.83 | 11 | 14.86 ± 2.71 | 11 | 3.68 ± 1.27 | 11 | 12.02 ± 7.20 |

| 8-PN | 11 | 44.28 ± 7.82 | 5 | 2.20 ± 1.26 | 6 | 1.44 ± 0.34 | 7 | 2.50 ± 0.46 |

3.3 Phase I & II metabolism

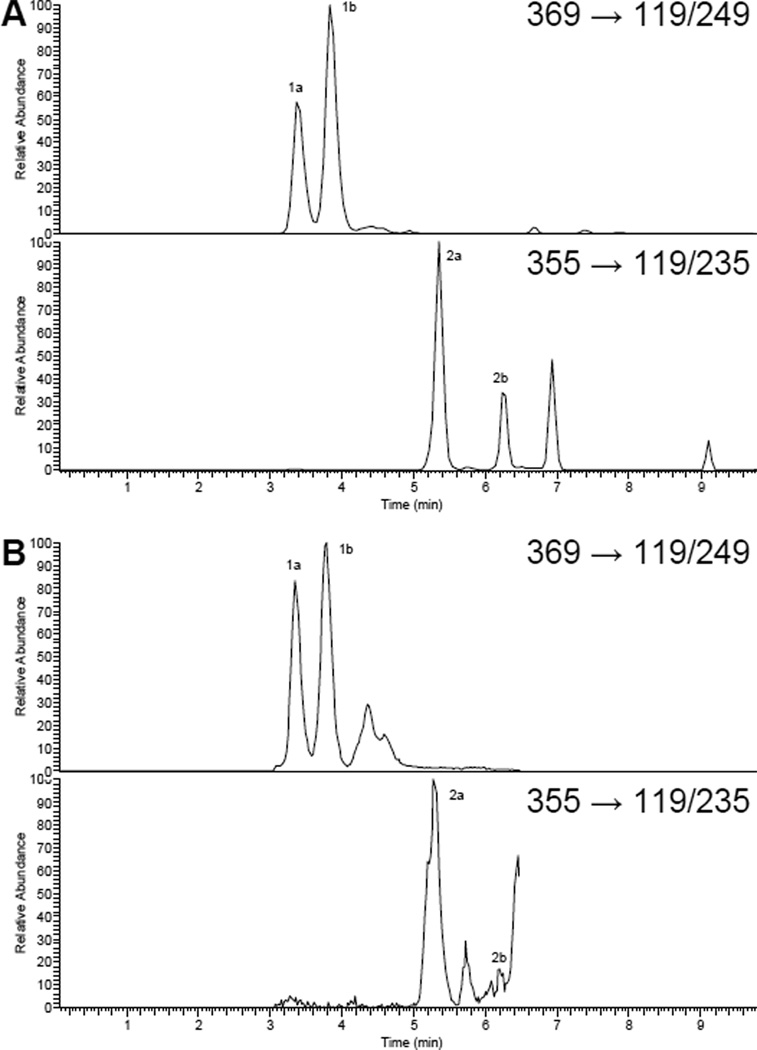

In hydrolyzed urine, both cis and trans alcohols of IX were observed in varying ratios (0.45–0.89) and were estimated to compose 9.3 ± 1.0% of the total IX equivalents (Fig. 2). Conversely, only one isomer of the monooxidation products of 8-PN, accounting for 12.3 ± 1.4% of the total 8-PN equivalents, was found. No phase I-metabolites were detected in serum or tissue samples.

FIGURE 2.

SRM trace chromatograms of cis and trans alcohols of IX (1a,b; m/z 369/119/249) and 8-PN (2a,b; m/z 355/119/235) (A) standards in control urine and (B) in hydrolyzed urine after prenylflavonoid supplementation.

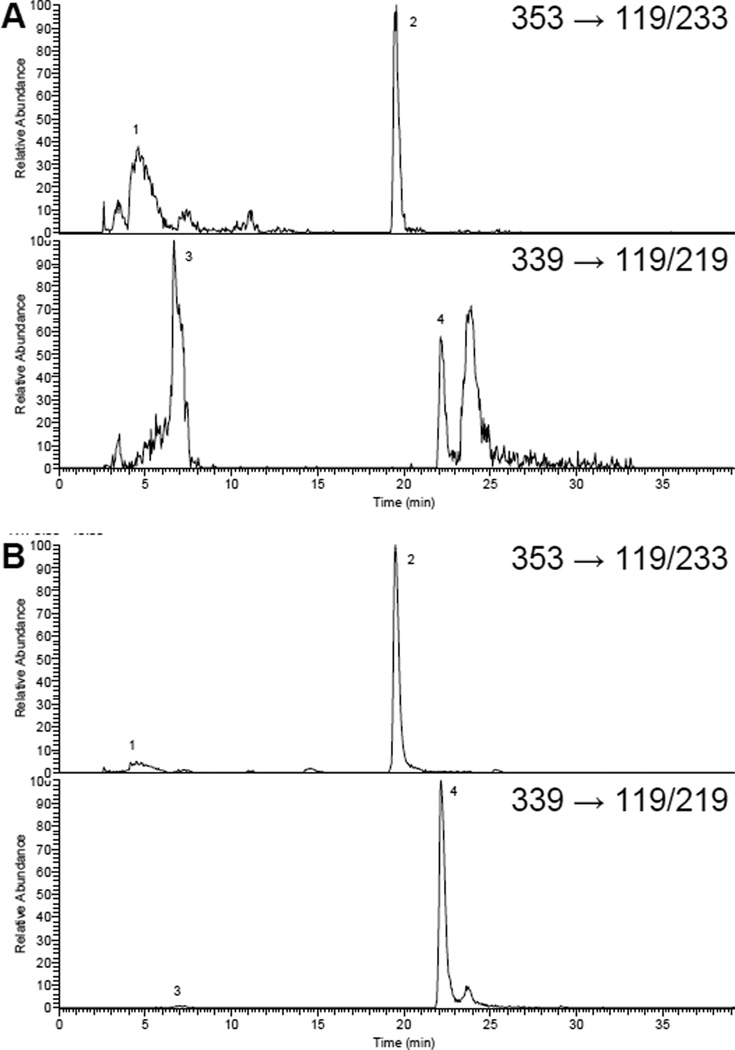

Upon enzymatic hydrolysis, urinary aglycone concentrations raised 10–20 times (IX: 13.3 ± 7.3; 8-PN: 11.6 ± 2.2), whereas the corresponding glucuronides disappeared (Fig. 3). Only traces of aglycones were observed in non-hydrolyzed serum and tissue samples suggesting an extensive glucuronidation (>90%).

FIGURE 3.

SRM trace chromatograms of monoglucuronides (1 and 3) and aglycones (2 and 4) of IX (m/z 353/119/233) and 8-PN (m/z 339/119/219) in (A) non-hydrolyzed and (B) hydrolyzed urine after prenylflavonoid supplementation.

3.4 Breast tissue disposition

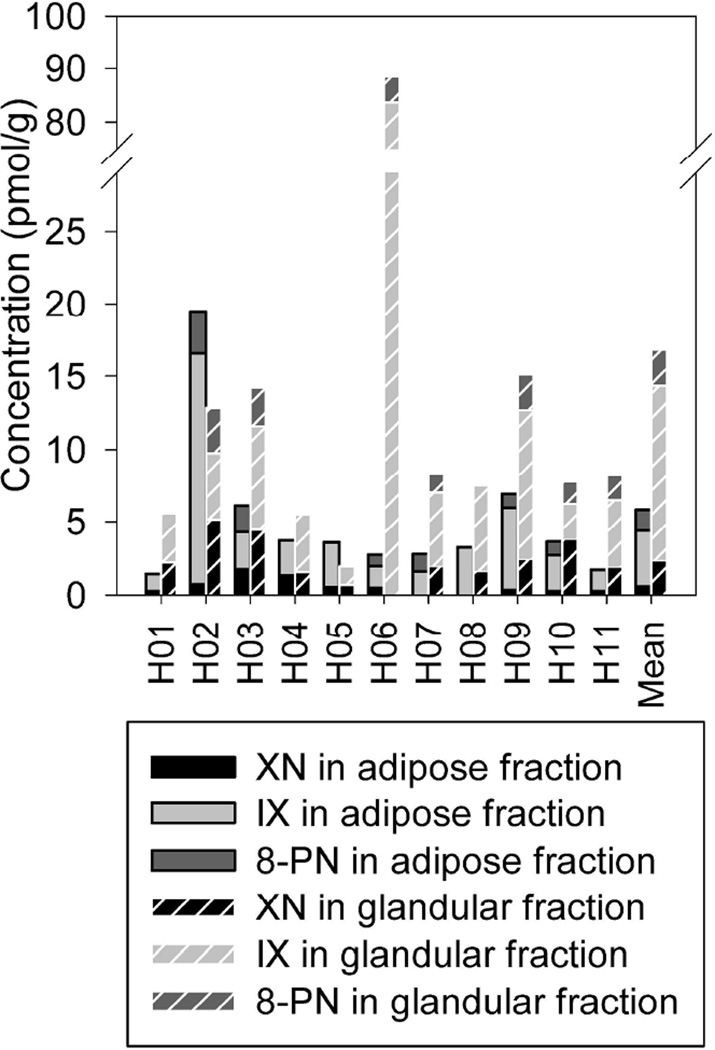

Compared to adipose breast tissue, higher mean XN, IX, and 8-PN concentrations were measured in glandular tissue (P= 0.011, P= 0.059, and P= 0.105, respectively), with an adipose/glandular tissue distribution of 22/78 (46/54-8/92), 34/66 (77/23-2/98), and 36/64 (49/51-14/86), respectively (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Disposition of XN, IX, and 8-PN in breast adipose and glandular tissue after prenylflavonoid supplementation. Mean values of duplicate extractions with single HPLC-MS/MS measurements.

The exposure to 8-PN was translated into E2-equivalents towards ERα and ERβ (E2α- and E2β-equivalents) assuming relative estrogenic potencies towards ERα of 1/10 and towards ERβ of 1/100 [11] and 98% attenuation due to glucuronidation [28]. Upon prenylflavonoid supplementation, breast tissue was exposed to phytoestrogen-derived E2α-equivalents (adipose fractions: 2.9 ± 0.7 fmol/g; glandular fractions: 5.0 ± 0.9 fmol/g), which were significantly lower than the measured unconjugated E2 tissue concentrations (adipose fractions: 384.6 ± 118.8 fmol/g, P= 0.009; glandular fractions: 241.6 ± 93.1 fmol/g, P< 0.001), and even lower (10-fold) E2β-equivalents.

4 Discussion

For the first time, the absorption, metabolism, and distribution of the prenylflavonoids XN, IX, and 8-PN were assessed in normal human breast tissue after hop-derived supplement intake. These hop-derived prenylflavonoids are known to possess pleiotropic bioactivities in vitro and in vivo. XN was shown to prevent carcinogen-induced preneoplastic lesions in mouse mammary gland organ cultures at nmol/L-concentrations (IC50: 20 nmol/L) [29]. As a full agonist of both ERα and ERβ [22], 8-PN can mimic or modulate estrogenic effects, depending on the endogenous estrogen levels and the target tissue. Longer-term (3 m) oral administration of high doses of pure 8-PN (equipotent human dose ~650 mg/d) had similar although milder effects than E2 (equipotent human dose ~7 mg/d) on the uterus, vagina, and mammary gland of ovariectomized rats [5,30]. Even though a 10-fold lower 8-PN dosing did not elicit estrogenic responses and other, ER-independent, mechanisms of action such as inhibition of aromatase activity (in vitro IC50 ~75 nmol/L, [31,32]) and angiogenesis (in vivo IC50 ~125 nmol/L, [33]), have been proposed, safety questions arise concerning unrestricted long-term use of freely accessible hop-derived food supplements [5,30,34]. However, to test and evaluate the suggested mechanisms of action on breast tissue, information on the levels of orally ingested prenylflavonoids that actually reach their target site in a bioactive conformation is needed. Our results indicate that, >12 h after last hop supplement intake, breast adipocytes and mammary gland epithelial cells were exposed to 0.05–0.50 pmol/g total prenylflavonoid aglycones and 2.5–20 pmol/g total prenylflavonoid glucuronides.

Although differences in time of sampling, dosing regimen, and formulation [35] often hamper sound comparisons between intervention trials, the urine and serum concentrations observed in this study were in line with previous reports on human exposure to prenylflavonoids [15,16,28,36]. The prenylflavonoid tissue levels were lower compared to the corresponding serum concentrations. Moreover, the lack of correlation between serum and tissue levels suggests that serum concentrations do not predict tissue disposition, as described for isoflavones [37,38].

In this study, cis and trans alcohols of IX and 8-PN, the most abundant human liver microsomal metabolites in vitro [14,21], were only detected in hydrolyzed urine samples. Similarly, Overk et al. found no 8-PN alcohol aglycones, but detected the monoglucuronides of these metabolites in non-hydrolyzed serum samples of rats [34]. Overall, phase I metabolism appeared to play a minor role (~10%) probably due to rapid conjugation to glucuronic acid and/or sulfate moieties in the intestinal epithelium and liver, as observed in in vitro-studies [39–41]. In accordance with previous reports on human exposure to 8-PN [28,36] and isoflavones [42–47], prenylflavonoid monoglucuronides were the predominant circulating metabolites. However, diglucuronides, sulfoglucuronides, mono- and disulfates were not monitored, but expected to be minor. Like serum, breast tissue contained mostly glucuronidated prenylflavonoids. Besides the studies of Bolca et al. [42] and Guy et al. [44], we are not aware of other reports on the disposition of phase II metabolites of phytoestrogens in human tissue.

The question is whether the exposure to XN, IX, and 8-PN, as observed in the present study, can result in any, protective or adverse, response related to breast carcinogenesis. Given the complexity of possible interactions, our information on in situ concentrations in addition to the current state of knowledge only allows for speculation on the potential activities of orally administered prenylflavonoids on breast tissue. The prevailing opinion is that treatments that trigger ER antagonistic effects, such as tamoxifen, and/or reduce E2 and estrone levels, such as aromatase inhibitors, are protective against breast cancer and favorably affect the course of breast cancer once diagnosed [48]. Therefore, we discuss our findings in the context of the potential of hop-derived prenylflavonoids to interfere with ER-mediated signaling and steroidogenesis.

Both ER isoforms, i.e., ERα and ERβ, are expressed in breast tissue and estrogen-induced cell proliferation and breast carcinogenesis have mainly been linked to ERα signaling whereas ERβ can antagonize ERα-dependent transcription [49]. Consequently, the balance between ERα and ERβ signaling has been hypothesized to determine the overall proliferative response to estrogens [49]. However, ligand-specific conformational changes in ER upon binding result in unique coregulator recruitment and transcriptional responses, as illustrated in animal studies e.g. [12]. The final outcome is, therefore, the result of the complex interplay and competition between all ligands, their metabolites, and even mixtures thereof, as far as their concentration and/or activity is physiologically relevant. Given the low exposure to XN, IX, and IX and 8-PN alcohol aglycones, all with weak or unknown estrogenic potencies [11,17], their contribution was not considered in this evaluation. Although glucuronidation may increase the bioactivity of its substrate in some cases (e.g., morphine [50]), estrogenicity is typically attenuated upon glucuronidation (e.g., tamoxifen [51] and phytoestrogens [52–54]). Still, glucuronides may act as a source of tissue aglycones by means of in situ glucuronidase activity, but concomitantly intracellular UDP-glucuronosyltransferases can catalyze the opposite reaction. Considering all prior remarks, the overall E2α- and E2β-equivalents were calculated based on the 8-PN aglycone exposure levels only, thereby highlighting the importance of the 8-PN producer phenotype. Still, both hop-derived E2α- and E2β-equivalents were negligible compared to the E2 tissue concentrations, which were in agreement with literature reports [26,27,55–58], suggesting that, in this case, hop consumption is unlikely to elicit important agonistic effects in human breast tissue. Yet, other bioactivities, directly or indirectly related to breast carcinogenesis, cannot be excluded based on these findings. Breast tissue E2 levels are maintained by active uptake of circulating estrogens and/or local synthesis (‘intracrine organ’ concept) [59]. The putative attenuation of in situ steroidogenesis through aromatase inhibition by XN, IX or 8-PN [31,32] is difficult to evaluate since these experiments were performed at supraphysiological concentrations (>10 nmol/L) and little or no information is currently available on the ability of phase I and II metabolites and mixtures of prenylflavonoids to modulate E2 synthesis and metabolism. In the present study, no significant differences in unconjugated E2 tissue levels were detected between the hop and control groups, but it was not designed to evaluate the effect of prenylflavonoid supplementation on the expression and/or activity of steroidogenic enzymes.

This work has some limitations. Firstly, sampling was done at a single time point, >12 h after last hop administration. Although steady-state levels are reached after 5 d of regular phytoestrogen intake throughout the day [60,61], diurnal fluctuations are expected because of the discontinued dosing during night, as shown for isoflavone serum concentrations [35]. Secondly, tissue was obtained from a small, heterogeneous group of generally healthy women with mammary hypertrophy and it is difficult to predict to what extent our findings can be extrapolated to the general (female) population. Breast tumors for instance, have a lowered ERβ expression [49], enhanced β-glucuronidase and decreased UDP-glucuronosyltransferase activities [62], and an overall altered estrogen metabolism resulting in higher E2 levels [26,57,58,63] and, therefore, a markedly different hormonal environment. Similarly, phytoestrogen disposition may be different in utero, during childhood, puberty or pregnancy and in men. Thirdly, the very short-term prenylflavonoid challenges applied in this study do not reflect dietary phytoestrogen exposure, which is often a combination of several phytochemicals with multiple and perhaps additive or interfering activities. Moreover, it is unclear whether and how other dietary constituents and doses of hop-derived phytoestrogens influence their disposition in breast tissue and, therefore, extrapolations should be done with caution. Finally, in vitro-data were used to translate these prenylflavonoid levels to an overall exposure to E2-equivalents. To strengthen these total estrogenicity estimates the use of ERα-and ERβ-driven reporter gene bioassays [64] is strongly recommended.

Taking these limitations and assumptions into consideration, we conclude that low doses of prenylflavonoids (~10 mg/d) are unlikely to elicit ER-mediated responses in breast tissue relevant to breast carcinogenesis. In addition, this study provides data for a more comprehensive evaluation of the safety of hop-derived phytoestrogens, based on physiologically relevant exposure levels and metabolites.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by grant P50AT00155 provided to the UIC/NIH Center for Botanical Dietary Supplements Research by the Office of Dietary Supplements, the National Institute of General Medicinal Sciences, the Office for Research on Women’s Health, and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, and by Metagenics Europe (Ostend, Belgium); however, the study and analyses were done independently. Selin Bolca benefits from a PhD grant of the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation through Science and Technology in Flanders (IWT-Vlaanderen).

List of Abbreviations

- 8-PN

8-prenylnaringenin

- E2

17β-estradiol

- E2α/β

E2-equivalents towards estrogen receptor α/β

- ER

estrogen receptor

- IX

isoxanthohumol

- RT

room temperature

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- XN

xanthohumol

Footnotes

None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Metzler M. Editorial - Hormonally active compounds in food. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007;51:763. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenbrand G. Isoflavones as phytoestrogens in food supplements and dietary foods for special medicalpurposes. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007;51:1305–1312. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenbrand G. Untitled - Answer to Dr. Messina's letter to the Editor. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52:737–738. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200890022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messina M. Conclusion that isoflavones exert estrogenic effects on breast tissue and may raise breast cancer risk unfounded. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52:299–300. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200890007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimoldi G, Christoffel J, Wuttke W. Morphologic changes induced by oral long-term treatment with 8-prenylnaringenin in the uterus, vagina, and mammary gland ofcastrated rats. Menopause. 2006;13:669–677. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000196596.90076.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messina M, Wu AH. Perspectives on the soy-breast cancer relation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;89:S1673–S1679. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stubert J, Gerber B. Isoflavones - mechanism of action and impact on breast cancer risk. Breast Care. 2009;4:22–29. doi: 10.1159/000200980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens JF, Taylor AW, Deinzer ML. Quantitative analysis of xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids in hops and beer by liquid chromatography-tandem massspectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 1999;832:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coldham NG, Sauer MJ. Identification, quantitation and biological activity of phytoestrogens in a dietary supplement for breast enhancement. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2001;39:1211–1224. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(01)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyerick A, Vervarcke S, Depypere H, Bracke M, De Keukeleire D. A first prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the use of a standardized hop extract to alleviate menopausal discomforts. Maturitas. 2006;54:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milligan SR, Kalita JC, Heyerick A, Rong H, et al. Identification of a potent phytoestrogen in hops (Humulus lupulus L.) and beer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;83:2249–2252. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.6.5887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hümpel M, Isaksson P, Schaefer O, Kaufmann U, et al. Tissue specificity of 8-prenylnaringenin: protection from ovariectomy induced bone loss with minimal trophic effects on the uterus. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;97:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo J, Nikolic D, Chadwick LR, Pauli GF, van Breemen RB. Identification of human hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of 8- prenylnaringenin and isoxanthohumol form hops (Humulus lupulus L.) Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006;34:1152–1159. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.008250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikolic D, Li Y, Chadwick LR, Pauli G, van Breemen RB. Metabolism of xanthohumol and isoxanthohumol, prenylated flavonoids from hops (Humulus lupulus L.) by human liver microsomes. J. Mass Spectrom. 2005;40:289–299. doi: 10.1002/jms.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolca S, Possemiers S, Maervoet V, Huybrechts I, et al. Microbial and dietary factors associated with the 8-prenylnaringenin producer phenotype: a dietary intervention trial with fifty healthy post-menopausal Caucasian women. Br. J. Nutr. 2007;98:950–959. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507749243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Possemiers S, Bolca S, Grootaert C, Heyerick A, et al. The prenylflavonoid isoxanthohumol from hops (Humulus lupulus L.) is activated into the potent phytoestrogen 8-prenylnaringenin in vitro and in the human intestine. J. Nutr. 2006;136:1862–1867. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.7.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zierau O, Hauswald S, Schwab P, Metz P, Vollmer G. Two major metabolites of 8-prenylnaringenin are estrogenic in vitro . J. steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;92:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson G, Barron D, Shimoi K, Terao J. In vitro biological properties of flavonoid conjugates found in vivo . Free Radic. Res. 2005;39:457–469. doi: 10.1080/10715760500053610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katzenellenbogen JA, OMalley BW, Katzenellenbogen BS. Tripartite steroid hormone receptor pharmacology: Interaction with multiple effector sites as a basis for the cell- and promoter-specific action of these hormones. Mol. Endocrinol. 1996;10:119–131. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.2.8825552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens JF, Ivancic M, Hsu VL, Deinzer ML. Prenylflavonoids from Humulus lupulus . Phytochem. 1997;44:1575–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolic D, Li Y, Chadwick LR, Grubjesic S, et al. Metabolism of 8-prenylnaringenin, a potent phytoestrogen from hops (Humulus lupulus), by human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004;32:272–279. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roelens F, Heldring N, Dhooge W, Bengtsson M, et al. Subtle side-chain modifications of the hop phytoestrogen 8-prenylnaringenin result in distinct agonist/antagonist activity profiles for estrogen receptors α and β. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:7357–7365. doi: 10.1021/jm060692n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartels H, Bohmer M. Eine Mikromethode zur Kreatininebestimmung. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1971;31:81–85. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(71)90467-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolca S, Wyns C, Possemiers S, Depypere H, et al. Cosupplementation of isoflavones, prenylflavonoids, and lignans alters human exposure to phytoestrogen-derived 17β-estradiol equivalents. J. Nutr. 2009;139:2293–2300. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Junge W, Wilke B, Halabi A, Klein G. Determination of reference intervals forserum creatinine creatinine excretion and creatinine clearance with an enzymatic and a modified Jaffé method. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2004;344:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chetrite GS, Cortes-Prieto J, Philippe JC, Wright F, Pasqualini JR. Comparison of estrogen concentrations, estrone sulfatase and aromatase activities in normal, and in cancerous, human breast tissues. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000;72:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dabrosin C. Increased extracellular local levels of estradiol in normal breast in vivo during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. J. Endocrinol. 2005;187:103–108. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rad M, Hümpel M, Schoemaker RC, Schleuning W-D, et al. Pharmacokinetics and systemic endocrine effects of the phyto-oestrogen 8-prenylnaringenin after single oral doses to postmenopausal women. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006;62:288–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerhaüser C, Alt A, Heiss E, Gamal-Eldeen A, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of xanthohumol, a natural product derived from hop. Mol. Cancer Therap. 2002;1:959–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christoffel J, Rimoldi G, Wuttke W. Effects of 8-prenylnaringenin on the hypothalamo-pituitary-uterine axis in rats after 3-months treatment. J. Endocrinol. 2006;188:397–405. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monteiro R, Becker H, Azevedo I, Calhau C. Effect of hop (Humulus lupulus L) flavonoids on aromatase (estrogen synthase) activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:2938–2943. doi: 10.1021/jf053162t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monteiro R, Faria A, Azevedo I, Calhau C. Modulation of breast cancer cell survival by aromatase inhibiting hop (Humulus lupulus L.) flavonoids. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;105:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pepper MS, Hazel SJ, Hümpel M, Schleuning W-D. 8-prenylnaringenin, a novel phytoestrogen, inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo . J. Cell. Physiol. 2004;199:98–107. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Overk CR, Guo J, Chadwick LR, Lantvit DD, et al. In vivo estrogenic comparisons of Trifolium pratense (red clover), Humulus lupulus (hops), and the pure compounds isoxanthohumol and 8-prenylnaringenin. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008;176:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner CD, Chatterjee LM, Franke AA. Effects of isoflavone supplements vs. soy foods on blood concentrations of genistein and daidzein in adults. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009;20:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaefer O, Bohlmann R, Schleuning W-D, Schulze-Forster K, Hümpel M. Development of a radioimmunoassay for the quantitative determination of 8-prenylnaringenin in biological matrices. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:2881–2889. doi: 10.1021/jf047897u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hargreaves DF, Potten CS, Harding C, Shaw LE, et al. Two-week dietary soy supplementation has an estrogenic effect on normal premenopausal breast. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;84:4017–4024. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maubach J, Depypere HT, Goeman J, Van Der Eycken J, et al. Distribution of soy-derived phytoestrogens in human breast tissue and biological fluids. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;103:892–898. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000124983.66521.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikolic D, Li Y, Chadwick LR, van Breemen RB. In vitro studies of intestinal permeability and hepatic and intestinal metabolism of 8-prenylnaringenin, a potent phytoestrogen form hops (Humulus lupulus L.) Pharm. Res. 2006;23:864–872. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9902-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruefer CE, Gerhaüser C, Frank N, Becker H, Kulling SE. In vitro phaseII metabolism of xanthohumol by human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and sulfotransferases. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005;49:851–856. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yilmazer M, Stevens JF, Buhler DR. In vitro glucuronidation of xanthohumol, a flavonoid in hop and beer, by rat and human liver microsomes. FEBS Lett. 2001;491:252–256. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolca S, Urpi-Sarda M, Blondeel P, Roche N, et al. Disposition of soyisoflavones in normal human breast tissue. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28854. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doerge DR, Chang HC, Churchwell MI, Holder CL. Analysis of soy isoflavone conjugation in vitro and in human blood using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2000;28:298–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guy L, Vedrine N, Urpi-Sarda M, Gil-Izquierdo A, et al. Orally administered isoflavones are present as glucuronides in the human prostate. Nutr. Cancer. 2008;60:461–468. doi: 10.1080/01635580801911761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hosoda K, Furuta T, Yokokawa A, Ogura K, et al. Plasma profiling of intact isoflavone metabolites by high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometric identification of flavone glycosides daidzin and genistin in human plasma after administration of kinako. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008;36:1485–1495. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.021006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shelnutt SR, Cimino CO, Wiggins PA, Ronis MJJ, Badger TM. Pharmacokinetics of the glucuronide and sulfate conjugates of genistein and daidzein in men and women after consumption of a soy beverage. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002;76:588–594. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Hendrich S, Murphy PA. Glucuronides are the main isoflavone metabolites in women. J. Nutr. 2003;133:399–404. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kloosterboer HJ, Lofgren L, von Schoulz E, vonSchoulz B, Verheul HAM. Estrogen and tibolone metabolite levels in blood and breast tissue of postmenopausal women recently diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer and treated with tibolone or placebo for 14 days. Reprod. Sci. 2007;14:151–159. doi: 10.1177/1933719106298679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor β - a new dimension in estrogen mechanism of action. J. Endocrinol. 1999;163:379–383. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1630379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frances B, Gout R, Monsarrat B, Cros J, Zajac JM. Further evidence that morphine-6-β-glucuronide is a more potent opioid agonist than morphine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;262:477–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng Y, Sun D, Sharma AK, Chen G, et al. Elimination of antiestrogenic effects of active tamoxifen metabolites by glucuronidation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007;35:1942–1948. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kinjo J, Tsuchihashi R, Morito K, Hirose T, et al. Interactions of phytoestrogens with estrogen receptors α and β (III). Estrogenic activities of soy isoflavone aglycones and their metabolites isolated from human urine. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004;27:185–188. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Song TT, Cunnick JE, Murphy PA, Hendrich S. Daidzein and genistein glucuronides in vitro are weakly estrogenic and activate human natural killer cells at nutritionally relevant concentrations. J. Nutr. 1999;129:399–405. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prichett LE, Atherton KM, Mutch E, Ford D. Glucuronidation of the soyabean isoflavones genistein and daidzein by human liver is related to levels of UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 activity and alters isoflavone response in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2008;19:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Falk RT, Gentzschein E, Stanczyk FZ, Brinton LA, et al. Measurement of sex steroid hormones in breast adipocytes: methods and implications. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1891–1895. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Brien SN, Anandjiwala J, Price TM. Differences in the estrogen content of breast adipose tissue in women by menopausal status and hormone use. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997;90:244–248. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pasqualini JR, Cortes-Prieto J, Chetrite G, Talbi M, Ruiz A. Concentrations of estrone, estradiol and their sulfates, and evaluation of sulfatase and aromatase activities in patients with breast fibroadenoma. Int. J. Cancer. 1997;70:639–643. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970317)70:6<639::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Landeghem AAJ, Poortman J, Nabuurs M, Thijssen JHH. Endogenous concentration and subcellular distribution of estrogens in normal and malignant human breast tissue. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2900–2906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pasqualini JR, Chetrite GS. Recent insight on the control of enzymes involved in estrogen formation and transformation in human breast cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;93:221–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mathey J, Lamothe V, Coxam V, Potier M, et al. Concentrations of isoflavones in plasma and urine of post-menopausal women chronically ingesting high quantities of soy isoflavones. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006;41:957–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsangalis D, Wilcox G, Shah NP, Stojanovska L. Bioavailability of isoflavone phytoestrogens in postmenopausal women consuming soya milk fermented with probiotic bifidobacteria. Br. J. Nutr. 2005;93:867–877. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Albin N, Massaad L, Toussaint C, Mathieu M-C, et al. Main drug-metabolizing enzyme systems in human breast tumors and peritumoral tissues. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3541–3546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pasqualini JR, Chetrite G, Blacker C, Feinstein MC, et al. Concentrations of estrone, estradiol, and estrone sulfate and evaluation of sulfatase and aromatase activities in pre- and postmenopausal breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996;81:1460–1464. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.4.8636351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li J, Lee L, Gong Y, Shen P, et al. Bioassays for estrogenic activity: development and validation of estrogen receptor (ERα/ERβ) and breast cancer proliferation bioassays to measure serum estrogenic activity in clinical trials. Assay Drug Develop. Technol. 2009;7:80–89. doi: 10.1089/adt.2008.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]