Abstract

Background/Objective:

Recent literature has identified links between vitamin B12 deficiency and depression.We compared the clinical response of SSRI-monotherapy with that of B12-augmentation in a sample of depressed patients with low normal B12 levels who responded inadequately to the first trial with the SSRIs.

Methods:

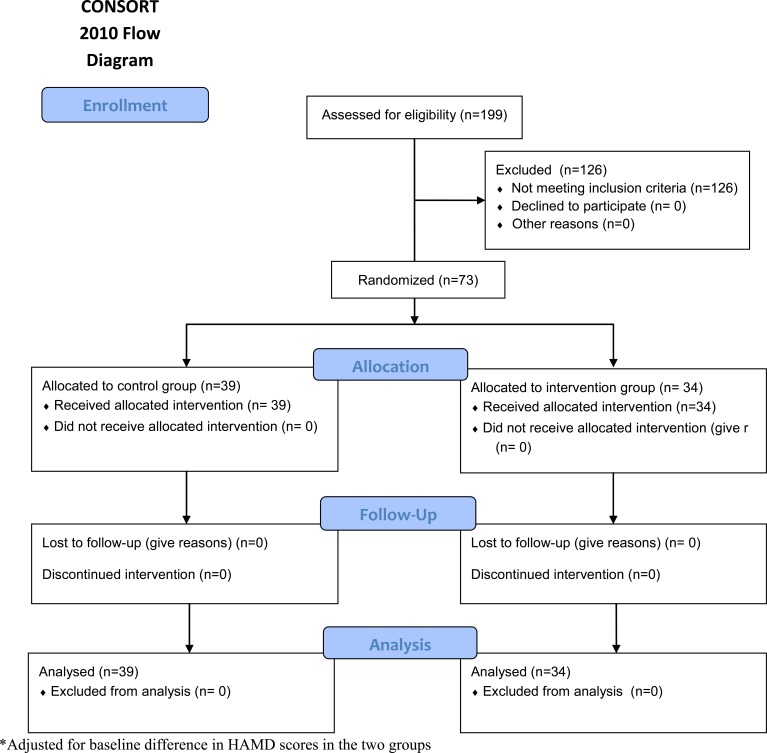

Patients with depression and low normal B12 levels were randomized to a control arm (antidepressant only) or treatment arm (antidepressants and injectable vitamin B12 supplementation).

Results:

A total of 199 depressed patients were screened. Out of 73 patients with low normal B12 levels 34 (47%) were randomized to the treatment group while 39 (53%) were randomized to the control arm. At three months follow up 100% of the treatment group showed at least a 20% reduction in HAM-D score, while only 69% in the control arm showed at least a 20% reduction in HAM-D score (p<0.001). The findings remained significant after adjusting for baseline HAM-D score (p=0.001).

Conclusion:

Vitamin B12 supplementation with antidepressants significantly improved depressive symptoms in our cohort.

Keywords: Depression, vitamin B12, antidepressants, RCT.

INTRODUCTION

Major Depressive Disorder is an important global public health problem associated with the significant burden and is projected to be the second leading cause of disability by 2020 [1]. Prevalence figures worldwide range between 4.2 – 17% and a systematic review of studies from Pakistan gave the estimates as high as 34% for anxiety and depressive disorders [2]. Clinical guidelines recommend the use of SSRIs as first-line treatment [3]. Remission rates in the acute phase of treatment are 30-40% and an overall 30% show poor response to anti-depressant monotherapy [4-6]. In such cases, addressing other co-morbid conditions is suggested in addition to upgrading or augmenting anti-depressant doses [3].

Pakistan, a developing country of 17 million people, is fraught with poverty, inadequate nutrition and underprivileged health systems. Several small-case studies from Pakistan show vitamin deficiencies to be common [7,8]. A small study from Islamabad on a clinical population of patients with megaloblastic anemia reported figures of 76% with vitamin B12 deficiency [9]. Although no large scale studies on general population are available here, studies from neighboring countries that share the culture and climate show vitamin deficiencies to be common [10-12]. A study on a healthy Indian population showed the prevalence of B12 deficiency to be 47% [13].

Vitamin B12 plays an important role in DNA synthesis and neurological function. Its deficiency is associated with hematological, neurological and psychiatric manifestations of which the latter includes irritability, personality change, depression, dementia and rarely, psychosis [14]. Recent literature has identified the links between this vitamin deficiency and depression. High B12 levels in serum are associated with good treatment response, high homocysteine levels which are common in folate / B12 deficiency and in those suffering from depression are associated with poor response to anti depressant treatment [15-17]. Hyperhomocysteinemia may have direct effects on neurotransmitters implicated in depression [18].

Randomized trials have shown that folate and other nutritional supplementations have a significant effect in treating the treatment-resistant depression [19,20]. Folate deficiency has also been linked with the delay in treatment response as well as relapse [21,22].

To date no adequately designed trial compares anti-depressant monotherapy with B12 augmentation. We aimed to compare the clinical response of antidepressants monotherapy with that of B12-augmentation in a sample of depressed patients with low normalB12 levels (190 pg/ml to 300 pg/ml).

METHODS

The study was designed as an open label randomized controlled trial (clinical trials registration number (Clinical Trials.gov ID NCT00939718). Patients were enrolled from outpatient clinics of the department of Psychiatry at Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi Pakistan from December 2009 - June 2010. Depression was defined as Patients scoring ≥ 16 on the 20-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression-Urdu version (HAM-D) [23,24].

Low normal B12 level was defined as B12 level ranging between 190 and 300 pg/ml. Patients with B12 deficiency (level below190 pg/ml) were not enrolled due to ethical reasons (patients with established B12 deficiency must be treated and not subjected to randomization).

Ethics Statement

A study protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Aga Khan University hospital. All patients signed an informed consent form.

Randomization and Masking

Patients with depression and low normal B12 levels were randomized by a computer program into the control arm (antidepressants only) or treatment arm (antidepressants and injectable vitamin B12 supplementation). The randomization was carried out using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet using the function “RAND” to generate uniform random numbers.

The randomized assignment was determined by partitioning the range of the random number. Randomization was not concealed for investigators. Antidepressants that were prescribed included either a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) with a dose equivalent of imipramine 100 mg to 250 mg/ day and the SSRIs dose equivalent of Fluoxetine 20 – 40 mg/day. Patients with concurrent unstable medical illness, history of manic episodes or psychotic illness, psychotic symptoms in a depressive episode, concurrent substance misuse and patients with suicidal ideation were excluded. Participants in the control arm only received the antidepressants. Those in the treatment arm received B12 intramuscular injectable as 1000 mcg every week during the 6 weeks in addition to the antidepressants.

Any adverse effects of oral medications and injections (B12) were monitored and documented on an adverse effects sheet in the patient folder.

A decline in HAM-D score of 20% or more from the baseline, indicating an improvement in depression, was defined as the primary outcome. The total change in HAM-D score from baseline to follow up was defined as a secondary outcome. Additional secondary outcomes included the follow up HAM-D score and a reduction in HAM-D score of 50% or more from the baseline. Follow up of the HAM-D score was recorded during 12 weeks by a research officer who was unaware of the patient’s randomization.

Statistical Considerations

A total of 248 patients equally allocated to the two groups provides at least 90 percent power, with a 5 percent type I error rate, using a two-sided hypothesis test. This calculation assumes an anticipated difference in the response rate of 20 percent between the two groups with a 30 percent response rate in the SSRI group and at least a 50 percent response rate in the combination treatment group. Considering a 15 percent dropout rate in each group, an additional sample of 44 patients equally divided into the two groups would be needed to yield a total required sample size of 292 patients. Therefore, the target sample size for each arm was 146.

Descriptive statistics were prepared for all characteristics including means and standard deviations for continuous measures and frequencies and percentages for categorical measures. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical baseline characteristics. Two-sample t tests were used to compare continuous baseline characteristics. Chi-square tests were used to examine the association between treatment and the 20% and 50% reductions in HAM-D outcomes. These analyses were extended to logistic regression to adjust for the baseline HAM-D score. Two-sample t tests were used to examine the association between treatment and the follow up HAM-D score or change in HAM-D score from baseline to follow up. These analyses were extended to analysis of covariance to adjust for the baseline HAM-D score. All hypotheses tests were two-sided and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 199 depressed patients were screened for the B12 levels. Vitamin B12 deficiency was present in 44 (22%) patients; 73 (36%) had low normal B12 levels and 82 (42%) had normal B12 levels. Patients with low B12 levels were given the prescriptions for B12 replacement therapy in addition to the antidepressants. These patients were not randomized. Out of 73 patients with low normal B12 levels 34 (47%) were randomized to the treatment group while 39 (53%) were randomized to the control arm. There were no significant differences between the two groups at baseline except for the higher depression scores in the treatment group (Table 1). No adverse effects or complications were noted in either group. For the primary outcome of 20% reduction in HAM-D score, significantly more subjects from the treatment group showed a 20% reduction unadjusted for baseline HAM-D score (100% vs. 69%; p < 0.001). Examining a50% reduction from baseline, this effect remained significant (44% vs. 5%; p < 0.001). We also adjusted the analyses of reduction for the baseline HAM-D score and our findings remained significant (Table 2). Additionally, the change in HAM-D score was significantly greater for the treatment group, unadjusted and adjusted for the baseline HAM-D score (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Shown as Mean ± Standard Deviation or Frequency (Percent)

| Treatment (n=34) | Control (n=39) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, in years | 37.68 ± 13.38 | 36.56 ± 12.28 | 0.71 |

| Total HAM-D | 23.21 ± 5.85 | 19.38 ± 5.70 | 0.006 |

| Vitamin B12 level | 238.49 ± 33.21 | 245.16 ± 27.82 | 0.36 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 18 (52.9) | 20 (51.3) | 0.89 |

| Female | 16 (47.1) | 19 (48.7) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single never married | 9 (26.5) | 13 (33.3) | 0.84 |

| Married | 21 (61.8) | 21 (53.9) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 4 (11.8) | 5 (12.8) |

Table 2.

Outcomes for Follow Up After 3 Months Shown as Mean ± Standard Deviation or Frequency (Percent)

| Treatment (n=34) | Control (n=39) | Unadjusted P-value | Adjusted* P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20% reduction in HAM-D score | 34 (100) | 27 (69.2) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| 50% reduction in HAM-D score | 15 (44.1) | 2 (5.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Follow up HAM-D score | 12.12 ± 5.12 | 14.38 ± 4.73 | 0.053 | <0.001 |

| Change in HAM-D score | 11.09 ± 4.58 | 5.00 ± 3.38 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Coexistence of depression and vitamin B12 deficiency are not uncommon. These patients are routinely treated with SSRI and B12 supplementation, however it is not well established whether the people with low normal B12 and co-occurring depression should also receive B12 supplementation. Our study tried to address this issue. Despite not attaining the targeted sample size, the findings appear significant. Vitamin B12 deficiency was present in 22% of our depressed population. This frequency is high in a non-vegetarian, relatively young, middle to upper income population of our patients. A recent study of healthy adults from Karachi showed a population based prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency (less than 200 pg/ml) in 9.74% people [25]. These findings indicate a substantial co-morbidity of B12 deficiency (22%) in our depressed patient population.

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized control trial in Pakistani population which has looked at clinically depressed patients with low B12 levels. We did not randomize B12 deficient patients due to ethical reasons. Low normal B12 levels were present in 36% of patients. These patients are often not treated with B12 supplementation. The findings of our study clearly indicate that these patients demonstrated significant improvement with B12 supplementation in addition to SSRI as compared to the control group even after adjustment for baseline HAM-D score. We think that these patients represent sub group within the clinically depressed population and a supplementation with B12 along with the conventional antidepressants may be a useful strategy in the treatment of depression in such cases.

We did not give sham injections to the control group. A placebo response due to injections may be responsible for the significant improvement in the treatment group. We also did not look at differences in response at specific doses of antidepressants nor did we stratify our groups on the basis of type of antidepressants prescribed. We also could not reach our sample size because we were not able to get another extension in our grant. Due to financial constraints we were not able to obtain final B12 levels. These are some of the limitations of our study. However, these findings have important clinical implications. B12 deficiency and low normal B12 levels are common and may be associated with depression and the inadequate response to antidepressant treatment in patients with depression. Vitamin B12 supplementation with antidepressants has significantly improved depressive symptoms in our group. Larger, multi-center studies are required to extend and replicate our findings.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors have no conflicts of interests to declare

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Authors would like to acknowledge Michele Shaffer PhD from School of Public Health, Penn State University for her valuable input in statistical analysis and manuscript revision.

FUNDING

Study funding was supported by University research council grant of Aga Khan University (G&C code; 70210)

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray C, Lopez A. The global burden of diseases a comprehensive assessment of Mortality and disability from diseases injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Boston Harvard School of Public Health. WHO and World Bank. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirza I, Jenkins R. Risk factors prevalence and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders in Pakistan systematic review. BMJ. 2004;328:794–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sohail Z, editor. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder DOI10.1176/appi.books.9780890423387.654001. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with Venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:234 –41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puech A, Montgomery SA, Prost JF, Solles A, Briley M. Milnacipran,a new serotonin and Noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor an overview of its antidepressant activity and clinical tolerability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;12(2):99–108. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199703000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antai-Otong D. Monotherapy Antidepressant.A Thing of the Past Implications for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Perspect Psych Care. 2007;43(3):142–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2007.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah RA, Qureshi MB, Khan AA. Magnitude of vitamin A deficiency in poor communities of the four selected districts of Punjab using (rapid assessment technique). Ann King Edward Med Coll. 2005;11(3):314–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan RM, Iqbal P. Deficiency of vitamin C in South Asia. Pak J Med Sci. 2006;22(3):347–55. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashim H, Tahir F. Frequency of vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiencies among patients with megaloblastic anemia. Ann Pak Inst Med Sci. 2006;2(3):192–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yajnik CS, Deshpande SS, Lubree HG, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia in rural and urban Indians. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:775–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakhrzadeh H, Ghotbi S, Pourebrahim R, et al. Total plasma homocysteine folate and vitamin b12 status in healthy Iranian adults the Tehran homocysteine survey 2003–2004)/a cross sectional population based study. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim HS, Heo YR. Plasma total homocysteine folate and vitamin B12 status in Korean adults. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2002;48(4):290–7 . doi: 10.3177/jnsv.48.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Refsum H, Yajnik CS, Gadkari M, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia and elevated methylmalonic acid indicate a high prevalence of cobalamin deficiency in Asian Indians. Am J Clin Nut. 2001;74(2):233–241. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robert C, Brown DL. Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:979–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hintikka J, Tolmunen T, Tanskanen A, Viinamäki H. High vitamin B12 level and good treatment outcome may be associated in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3:17–22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiemeier H, vanTuijl HR, Hofman A, Meijer J, Kiliaan AJ, Breteler MM. Vitamin B12 folate and homocysteine in depression the Rotterdam Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(12):2099–01. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachdev PS, Parslow RA, Lux O, et al. Relationship of homocysteine folic acid and vitamin B12 with depression in a middle aged community sample. Psychol Med. 2005;35(4):529–38. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottiglieri T, Laundy M, Crellin R, Toone BK, Carney MW, Reynolds EH. Homocysteine folate methylation and monoamine metabolism in depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:228–232. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alpert JE, Mischoulon D. Folinic acid (Leucovorin) as an adjunctive treatment for SSRI-refractory depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2002;14(1):33–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1015271927517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fava M, Borus JS. Folate vitamin B12 and homocysteine in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(3):426–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papakostas GI, Peterson T. Serum folate vitamin B12 and homocysteine in major depressive disorder Part I.predictors of clinical response in fluoxetine-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1090–5. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papakostas GI, Peterson T. Serum folate vitamin B12 and homocysteine in major depressive disorder Part II predictors of clinical response in fluoxetine-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1096–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaudhry HR, Qureshi Z, Tareen IA, Yazdani I. Efficacy and tolerability of Paroxetine 20 mg daily in the treatment of depression and depression associated anxiety. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52(11):518–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yakub M, Iqbal MP, Kakepoto GN, et al. High prevalence of mild hyperhomocystienemia and folate B12 and B6 deficiencies in an urban population in Karachi Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2010;26(4):923–929. [Google Scholar]