Abstract

Precision-recall (PR) curves and the areas under them are widely used to summarize machine learning results, especially for data sets exhibiting class skew. They are often used analogously to ROC curves and the area under ROC curves. It is known that PR curves vary as class skew changes. What was not recognized before this paper is that there is a region of PR space that is completely unachievable, and the size of this region depends only on the skew. This paper precisely characterizes the size of that region and discusses its implications for empirical evaluation methodology in machine learning.

1. Introduction

Precision-recall (PR) curves are a common way to evaluate the performance of a machine learning algorithm. PR curves illustrate the tradeoff between the proportion of positively labeled examples that are truly positive (precision) as a function of the proportion of correctly classified positives (recall). In particular, PR analysis is preferred to ROC analysis when there is a large skew in the class distribution. In this situation, even a relatively low false positive rate can produce a large number of false positives and hence a low precision (Davis & Goadrich, 2006). Many applications are characterized by a large skew in the class distribution. In information retrieval (IR), only a few documents are relevant to a given query. In medical diagnoses, only a small proportion of the population has a specific disease at any given time. In relational learning, only a small fraction of the possible groundings of a relation are true in a database.

The area under the precision-recall curve (AUCPR) often serves as a summary statistic when comparing the performance of different algorithms. For example, IR systems are frequently judged by their mean average precision, or MAP (not to be confused with the same acronym for “maximum a posteriori”), which is an approximation of the mean AUCPR over the queries (Manning et al., 2008). Similarly, AUCPR often serves as an evaluation criteria for statistical relational learning (SRL) (Kok & Domingos, 2010; Davis et al., 2005; Sutskever et al., 2010; Mihalkova & Mooney, 2007) and information extraction (IE) (Ling & Weld, 2010; Goadrich et al., 2006). Additionally, some algorithms, such as SVM-MAP (Yue et al., 2007) and SAYU (Davis et al., 2005), explicitly optimize the AUCPR of the learned model.

There is a growing body of work that analyzes the properties of PR curves (Davis & Goadrich, 2006; Clémençon & Vayatis, 2009). Still, PR curves and AUCPR are frequently treated as a simple substitute in skewed domains for ROC curves and area under the ROC curve (AUCROC), despite the known differences between PR and ROC curves. These differences include that for a given ROC curve the corresponding PR curve varies with class skew (Davis & Goadrich, 2006). A related, but previously unrecognized, distinction between the two types of curves is that, while any point in ROC space is achievable, not every point in PR space is achievable. That is, for a given data set it is possible to construct a confusion matrix that corresponds to any (false positive rate, true positive rate) pair, but it is not possible to do this for every (recall, precision) pair.1

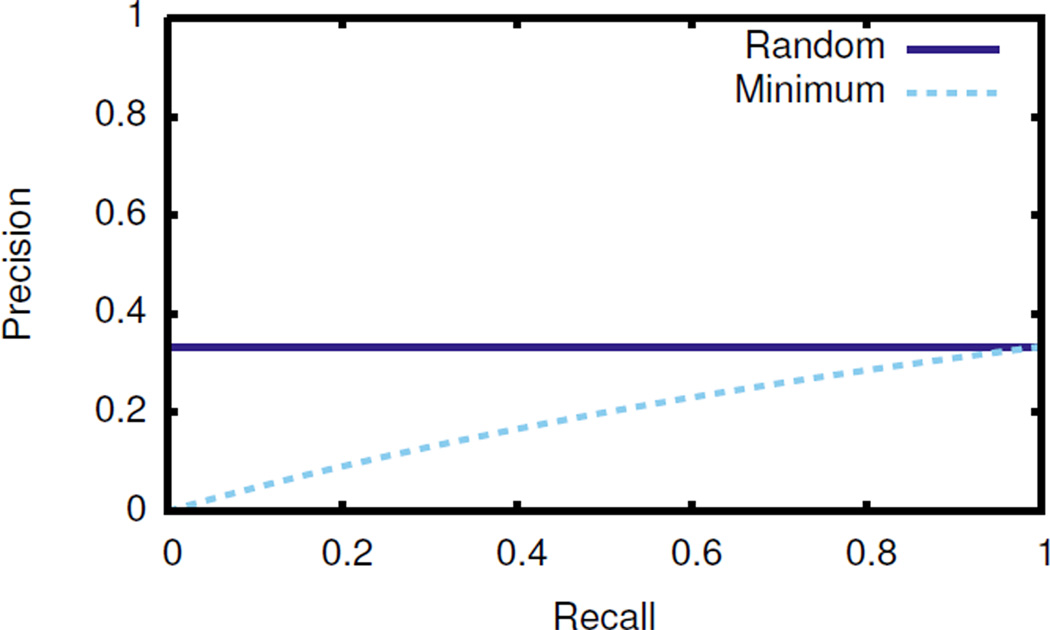

We show that this distinction between ROC space and PR space has major implications for the use of PR curves and AUCPR in machine learning. The foremost is that the unachievable points define a minimum PR curve. The area under the minimum PR curve constitutes a portion of AUCPR that any algorithm, no matter how poor, is guaranteed to obtain “for free.” Figure 1 illustrates the phenomenon. Interestingly, we prove that the size of the unachievable region is only a function of class skew and has a simple, closed form.

Figure 1.

Minimum PR curve and random guessing curve at a skew of 1 positive for every 2 negative examples.

The unachievable region can influence algorithm evaluation and even behavior in many ways. Even for evaluations using F1 score, which only consider a single point in PR space, the unachievable region has subtle implications. When averaging AUCPR over multiple tasks (e.g., SRL target predicates or IR queries), the area under the minimum PR curve alone for a non-skewed task may outweigh the total area for all other tasks. A similar effect can occur when the folds used for cross-validation do not have the same skew. Downsampling that changes the skew will also change the minimum PR curve. In algorithms that explicitly optimize AUCPR or MAP during training, algorithm behavior can change substantially with a change in skew. These undesirable effects of the unachievable region can be at least partially offset with straightforward modifications to AUCPR, which we describe.

2. Achievable and Unachievable Points in PR Space

We first precisely define the notion of an achievable point in PR space. Then we provide an intuitive example to illustrate the concept of an unachievable point. Finally, in Theorems 1 and 2 we present our central theoretical contributions that formalize the notion of the unachievable region in PR space.

We assume familiarity with precision, recall, and confusion matrices (see Davis and Goadrich (2006) for an overview). We use p for precision, r for recall, and tp, fp, fn, tn for the number of true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives, respectively.

Consider a data set D with n = pos + neg examples, where pos is the number of positive examples and neg is the number of negative examples. A valid confusion matrix for D is a tuple (tp, fp, fn, tn) such that tp, fp, fn, tn ≥ 0, tp + fn = pos and fp + tn = neg. We use , the proportion of examples that are positive, to quantify the skew of D. Following convention, highly skewed refers to π near 0 and non- or less skewed to π near 0.5.

Definition 1. For a data set D, an achievable point in PR space is a point (r, p) such that there exists a valid confusion matrix with recall r and precision p.

2.1. Unachievable Points in PR Space

One can easily show that, like in ROC space, each valid confusion matrix, where tp > 0, defines a single and unique point in PR space. In PR space, both recall and precision depend on the tp cell of the confusion matrix, in contrast to the true positive rate and false positive rate used in ROC space. This dependence, together with the fact that a specific data set contains a fixed number of negative and positive examples, imposes limitations on what precisions are possible for a particular recall.

To illustrate this effect, consider a data set with pos = 100 and neg = 200. Table 1(a) shows a valid confusion matrix with r = 0.2 and p = 0.2. Consider holding precision constant while increasing recall. Obtaining r = 0.4 is possible with tp = 40 and fn = 60. Notice that keeping p = 0.2 requires increasing fp from 80 to 160. With a fixed number of negative examples in the data set, increases in fp cannot continue indefinitely. For this data set, r = 0.5 with p = 0.2 is possible by using all negatives as false positives (so tn = 0). However, maintaining p = 0.2 for any r > 0.5 is impossible. Table 1(b) illustrates an attempted confusion matrix with r = 0.6 and p = 0.2. Achieving p = 0.2 at this recall requires fp > neg. This forces tn < 0 and makes the confusion matrix invalid.

Table 1.

(a) Valid confusion matrix with r = 0.2 and p = 0.2 and (b) invalid confusion matrix attempting to obtain r = 0.6 and p = 0.2.

| (a) Valid | ||

|---|---|---|

| Actual | ||

| Label | Pos | Neg |

| Pos | 20 | 80 |

| Neg | 80 | 120 |

| Total | 100 | 200 |

| (b) Invalid | ||

|---|---|---|

| Actual | ||

| Label | Pos | Neg |

| Pos | 60 | 240 |

| Neg | 40 | −40 |

| Total | 100 | 200 |

The following theorem formalizes this restriction on achievable points in PR space.

Theorem 1. Precision (p) and recall (r) must satisfy,

| (1) |

where π is the skew.

Proof. Starting from the definition of precision,

since the false positives cannot be greater than the number of negatives. tp = rπn from the definition of recall, and we can reasonably assume the data set is non-empty (n > 0) so the ns cancel out. Thus

If a point in PR space satisfies Eq. (1), we say it is achievable. Note that a point’s achievability depends solely on the skew and not on a data set’s size. Thus we often refer to achievability in terms of the skew and not in reference to any particular data set.

2.2. Unachievable Region in PR Space

Theorem 1 gives a constraint that each achievable point in PR space must satisfy. For a given skew, there are many points that are unachievable, and we refer to his collection of points as the unachievable region of PR space. This subsection studies the properties of he unachievable region.

Eq. (1) makes no assumptions about a model’s performance. Consider a model that gives the worst possible ranking where every negative example is ranked ahead of every positive example. Building a PR curve based on this ranking means placing one PR point at (0, 0) and a second PR point at . Davis and Goadrich (2006) provide the correct method for interpolating between points in PR space; interpolation is non-linear in PR space but is linear between the corresponding points in ROC space. Interpolating between the two known points gives intermediate points with recall of and precision of , for 0 ≤ i ≤ pos. This is the equality case from Theorem 1, so Eq. (1) is a tight lower bound on precision. We call the curve produced by this ranking the minimum PR curve because it lies on the boundary between the achievable and unachievable regions of PR space. For a given skew, all achievable points are on or above the minimum PR curve.

The minimum PR curve has an interesting implication for AUCPR and average precision. Any model must produce a PR curve that lies above the minimum PR curve. Thus, the AUCPR score includes the size of the unachievable region “for free.” In the following theorem, we provide a closed form solution for calculating the area of the unachievable region.

Theorem 2. The area of the unachievable region in PR space and the minimum AUCPR, for skew π, is

| (2) |

Proof. Since Eq. (1) gives a lower bound for the precision at a particular recall, the unachievable area is the area below the curve .

See Figure 3 for AUCPRMIN at different skews.

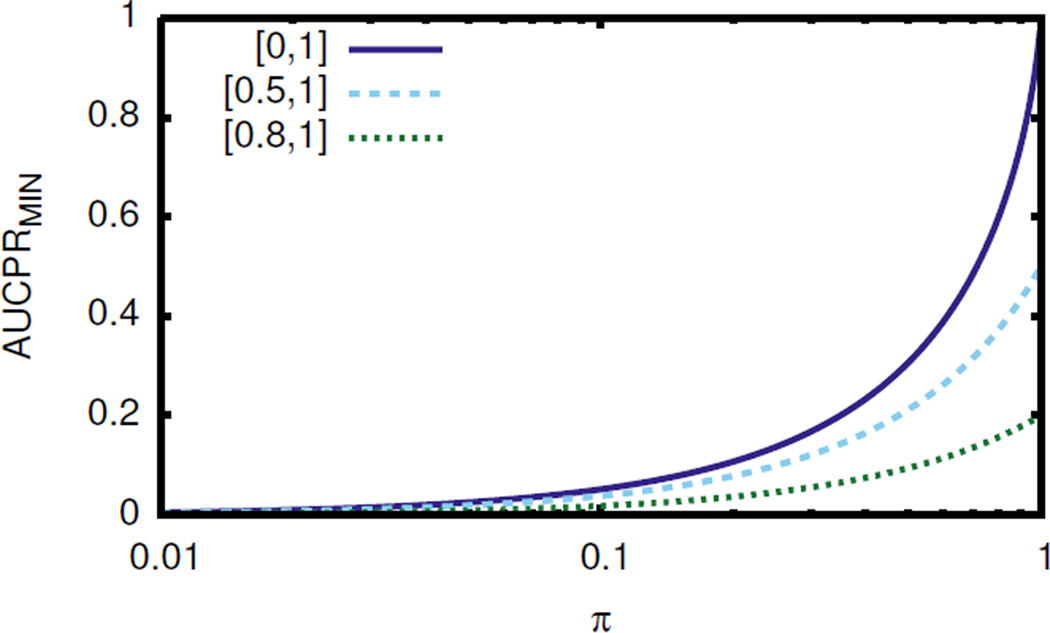

Figure 3.

Minimum AUCPR versus π for area calculated over recall in [0, 1] (entire PR curve), [0.5, 1], and [0.8, 1].

Similar to AUCPR, Eq. (1) also defines a minimum for average precision (AP). Average precision is the mean precision after correctly labeling each positive example in the ranking, so the minimum takes the form of a discrete summation. Unlike AUCPR, which is calculated from interpolated curves, the minimum AP depends on the number of positive examples because that controls the number of terms in the summation.

Theorem 3. The minimum AP, for pos and neg positive and negative examples, respectively, is

Proof.

This precisely captures the natural intuition that the worst AP involves labeling all negatives examples as positive before starting to label the positives.

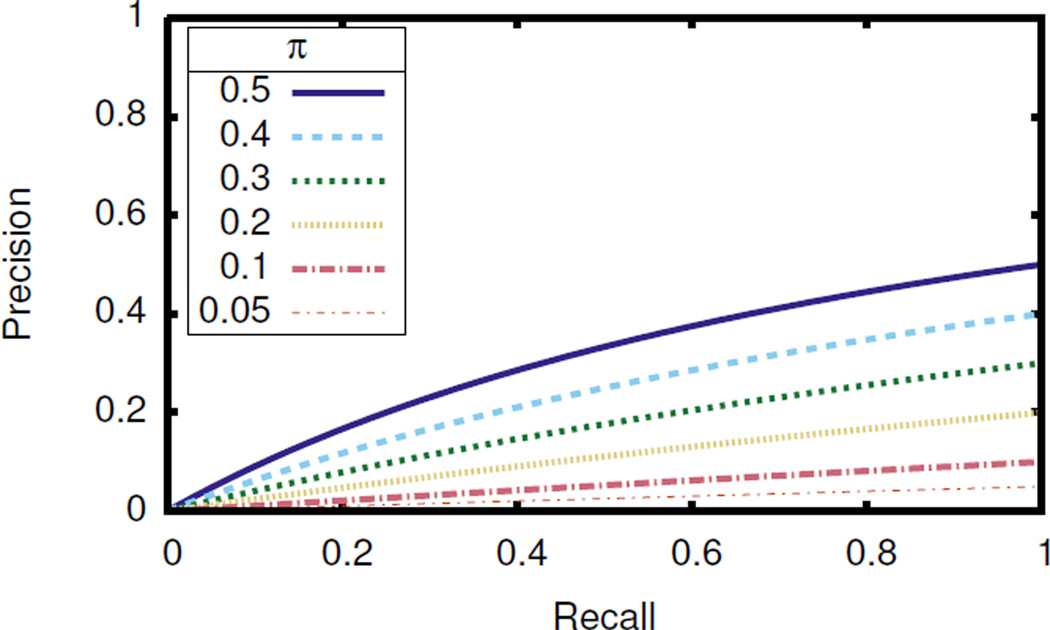

The existence of the minimum AUCPR and minimum AP can affect the qualitative interpretation of a model’s performance. For example, changing the skew of a data set from 0.01 to 0.5 (e.g., by subsampling the negative examples (Natarajan et al., 2011; Sutskever et al., 2010)) increases the minimum AUCPR by approximately 0.3. This leads to an automatic jump of 0.3 in AUCPR simply by changing the data set and with absolutely no change to the learning algorithm.

Since the majority of the unachievable region is at higher recalls, the effect of AUCPRMIN becomes more pronounced when restricting the area calculation to high levels of recall. Calculating AUCPR for recalls above a threshold is frequently done due to the high variance of precision at low recall or because the learning problem requires high recall solutions (e.g., medical domains such as breast cancer risk prediction). Corollary 4 gives the formula for computing AUCPRMIN when the area is calculated over a restricted range of recalls. See Figure 3 for minimum AUCPR when calculating area over restricted recall.

Corollary 4. For calculation of AUCPR over recalls in [a, b] where 0 ≤ a < b ≤ 1,

3. PR Space Metrics that Account for Unachievable Region

The unachievable region represents a lower bound on AUCPR and it is important to develop evaluation metrics that account for this. We believe that any metric A′ that replaces AUCPR should satisfy at least the following two properties. First, A′ should relate to AUCPR. Assume AUCPR was used to estimate the performance of classifiers C1, …, Cn on a single test set. If AUCPR(Ci, testD) > AUCPR(Cj, testD), then A′(Ci, testD) > A0(Cj, testD), as test set testD’s skew affects each model equally. Note that this property may not be appropriate or desirable when aggregating scores across multiple test sets, as done in cross validation, because each test set may have a different skew. Second, A′ should have the same range for every data set, regardless of skew. This is necessary, though not sufficient, to achieve meaningful comparisons across data sets. AUCPR does not satisfy the second requirement because, as shown in Theorem 2, its range depends on the data set’s skew.

We propose the normalized area under the PR curve (AUCNPR). From AUCPR, we subtract the minimum AUCPR, so the worst ranking has a score of 0. We then normalize so the best ranking has a score of 1.

where AUCPRMAX = 1 when calculating area under the entire PR curve and AUCPRMAX = b − a when restricting recall to a ≤ r ≤ b.

Regardless of skew, the best possible classifier will have an AUCNPR of 1 and the worst possible classifier will have an AUCNPR of 0. AUCNPR also preserves the ordering of algorithms on the same test set since AUCPRMAX and AUCPRMIN are constant for the same data set. Thus, AUCNPR satisfies our proposed requirements for a replacement of AUCPR. Furthermore, by accounting for the unachievable region, it makes comparisons between data sets with different skews more meaningful than AUCPR.

An alternative to AUCNPR would be to normalize based on the AUCPR for random guessing, which is simply π. This has two drawbacks. First, the range of scores depends on the skew, and therefore is not consistent across different data sets. Second, it can result in a negative score if an algorithm performs worse than random guessing, which seems counter-intuitive for an area under a curve.

A discussion of degenerate data sets with π = 0 or π = 1, where AUCPRMIN and AUCNPR are undefined, is in our technical report (Boyd et al., 2012).

4. Discussion and Recommendations

We believe all practitioners using evaluation scores based on PR space (e.g., PR curves, AUCPR, AP, F1) should be cognizant of the unachievable region and how it may affect their analysis.

Visually inspecting the PR curve or looking at an AUCPR score often gives an intuitive sense for the quality of an algorithm or difficulty of a task or data set. If the skew is extremely large, the effect of the very small unachievable region is negligible on PR analysis. However, there are many instances where the skew is closer to 0.5 and the unachievable area is not insignificant. With π = 0.1, AUCPRMIN ≈ 0.05, and it increases as π approaches 0.5. AUCPR is used in many applications where π > 0.1 (Hu et al., 2009; Sonnenburg et al., 2006; Liu & Shriberg, 2007). Thus a general awareness of the unachievable region and its relationship to skew is important when casually comparing or inspecting PR curves and AUCPR scores. A simple recommendation that will make the unachievable region’s impact on results clear is to always show the minimum PR curve on PR curve plots.

Next, we discuss several specific situations where the unachievable region is highly relevant.

4.1. Aggregation for Cross-Validation

In cross validation, stratification typically allows different folds to have similar skews. However, particularly in relational domains, this is not always the case. In relational domains, stratification must consider fold membership constraints imposed by links between objects that, if violated, would bias the results of cross validation. For example, consider the bioinformatics task of protein secondary structure prediction. Putting amino acids from the same protein in different folds has two drawbacks. First, it could bias the results as information about the same protein is in both the train and test set. Second, it does not properly simulate the ultimate goal of predicting the structure of entirely novel proteins. Links between examples occur in most relational domains, and placing all linked items in the same fold can lead to substantial variation in the skew of the folds. Since the different skews yield different AUCPRMIN, care must be taken when aggregating results to create a single summary statistic of an algorithm’s performance.

Cross validation assumes that each fold is sampled from the same underlying distribution. Even if the skew varies across folds, the merged data set is the best estimate of the underlying distribution and thus the overall skew. Ideally, aggregate descriptions, like a PR curve or AUCPR, should be calculated on a single, merged data set. Merging directly compares probability estimates for examples in different folds and assumes that the models are calibrated. Unfortunately, this is rarely a primary goal of machine learning and learned models tend to be poorly calibrated (Forman & Scholz, 2010).

With uncalibrated models, the most common practice is to average the results from each fold. For AUCPR, the summary score is the mean of the AUCPR from each fold. For a PR curve, vertical averaging of the individual PR curves from each fold provides a summary curve. In both cases, averaging fails to account for any difference in the unachievable regions that arise due to variations in class skew. As shown in Theorem 2, the range of possible AUCPR values varies according to a fold’s skew. Similarly, when vertically averaging PR curves, a particular recall level will have varying ranges of potential precision values for each fold if the folds have different skews. Even a single fold, which has much higher precision values due to a substantially lower skew, can cause a higher vertically averaged PR curve because of its larger unachievable region. Failing to account for fold-by-fold variation in skew can lead to overly optimistic assessments when using straight-forward averaging.

We recommend averaging AUCNPR instead of AUCPR when evaluating area under the curve. Averaging AUCNPR, which has the same range regardless of skew, helps reduce (but not eliminate) skew’s effect compared to averaging AUCPR. A similar normalization approach for summarizing the PR curve leads to a non-linear transformation of PR space that can change the area under the curves in unexpected ways. An effective method for generating a summary PR curve that preserves measures of area in a satisfying way and accounts for the unachievable region would be useful and is a promising area of future research.

4.2. Aggregation among Different Tasks

Machine learning algorithms are commonly evaluated on several different tasks. This setting differs from cross-validation because each task is not assumed to have the same underlying distribution. While the tasks may be unrelated (Tang et al., 2009), often they come from the same domain. For example, the tasks could be the truth values of different predicates in a relational domain (Kok & Domingos, 2010; Mihalkova & Mooney, 2007) or different queries in an IR setting (Manning et al., 2008). Often, researchers report a single, aggregate score by averaging the results across the different tasks. However, the tasks can potentially have very different skews, and hence different minimum AUCPR. Therefore, averaging AUCNPR scores, which (somewhat) control for skew, is preferred to averaging AUCPR.

In SRL, researchers frequently evaluate algorithms by reporting the average AUCPR over a variety of tasks in a single data set (Mihalkova & Mooney, 2007; Kok & Domingos, 2010). As a case study, consider the commonly used IMDB data set. Here, the task is to predict the probability that each possible grounding of each predicate is true. Across all predicates in IMDB the skew of true groundings is relatively low (π = 0.06), but there is significant variation in the skew of individual predicates. For example, the gender predicate has a skew close to π = 0.5, whereas a predicate such as genre has a skew closer to π = 0.05. While presenting the mean AUCPR across all predicates is a good first approach, it leads to averaging values that do not all have the same range. For example, the gender predicate’s range is [0.31, 1.0] while the genre predicate’s range is [0.02, 1.0]. Thus, an AUCPR of 0.4 means very different things on these two predicates. For the gender predicate, this score is worse than random guessing, while for the genre predicate this is a reasonably high score. In a sense, all AUCPR scores of 0.4 are not created equal, but averaging the AUCPR treats them as equals.

Table 2 shows AUCPR and AUCNPR for each predicate on a Markov logic network model learned by the LSM algorithm (Kok & Domingos, 2010). Notice the wide range of scores and that AUCNPR gives a more conservative overall estimate. AUCNPR is still sensitive to skew, so an AUCNPR of 0.4 in the aforementioned predicates still does not imply completely comparable performances, but it is closer than AUCPR.

Table 2.

Average AUCPR and AUCNPR scores for each predicate in the IMDB set. Results are for the LSM algorithm from Kok and Domingos (2010). The range of scores shows the difficulty and skews of the prediction tasks vary greatly. By accounting for the (potentially large) unachievable regions, AUCNPR yields a more conservative overall estimate of performance.

| Predicate | AUCPR | AUCNPR |

|---|---|---|

| actor | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| director | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| gender | 0.509 | 0.325 |

| genre | 0.624 | 0.611 |

| movie | 0.267 | 0.141 |

| workedUnder | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| mean | 0.733 | 0.680 |

4.3. Downsampling

Downsampling is common when learning on highly skewed tasks. Often the downsampling alters the skew on the train set (e.g., subsampling the negatives to facilitate learning, or using data from case-control studies) such that it does not reflect the true skew. PR analysis is frequently used on the downsampled data sets (Sonnenburg et al., 2006; Natarajan et al., 2011; Sutskever et al., 2010). The sensitivity of AUCPR and related scores makes it important to recognize, and if possible quantify, the effect of downsampling on evaluation metrics.

The varying size of the unachievable region provides an explanation and quantification of some of the dependence of PR curves and AUCPR on skew. Thus, AUCNPR, which adjusts for the unachievable region, should be more stable than AUCPR to changes in skew. To explore this, we used SAYU (Davis et al., 2005) to learn a model for the advisedBy task in the UW-CSE domain for several downsampled train sets. Table 3 shows the AUCPR and AUCNPR scores on a test set downsampled to the same skew as the train set and on the original (i.e., non-downsampled) test set. AUCNPR has less variance than AUCPR. However, there is still a sizable difference between the scores on the downsampled test set and the original test set. As expected, the difference increases as the ratio approaches 1 positive to 1 negative. At this ratio, even the AUCNPR score on the downsampled data is more than twice the score on the original skew. This is a massive difference and it is disconcerting that it occurs simply by changing the data set skew. An intriguing area for future research is to investigate scoring metrics that either are less sensitive to skew or permit simple and accurate transformations that facilitate comparisons between different skews.

Table 3.

AUCPR and AUCNPR scores for SAYU on UWCSE advisedBy task for different train set skews. The downsampled columns report scores on a test set with the same downsampled skew as the train set. The original skew columns report scores on the original test set with a ratio of 1 positive to 24 negatives (π = 0.04).

| Downsampled | Original Skew | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | AUCPR | AUCNPR | AUCPR | AUCNPR |

| 1:1 | 0.851 | 0.785 | 0.330 | 0.316 |

| 1:2 | 0.740 | 0.680 | 0.329 | 0.315 |

| 1:3 | 0.678 | 0.627 | 0.343 | 0.329 |

| 1:4 | 0.701 | 0.665 | 0.314 | 0.299 |

| 1:5 | 0.599 | 0.560 | 0.334 | 0.320 |

| 1:10 | 0.383 | 0.352 | 0.258 | 0.242 |

| 1:24 | 0.363 | 0.349 | 0.363 | 0.349 |

4.4. F1 Score

A commonly used evaluation metric for a single point in PR space is the Fβ family,

where β > 0 is a parameter to control the relative importance of recall and precision (Manning et al., 2008). Most frequently, the F1 score (β = 1), which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, is used. We focus our discussion on the F1 score, but similar analysis applies to Fβ. Figure 4 shows contours of the F1 score over PR space.

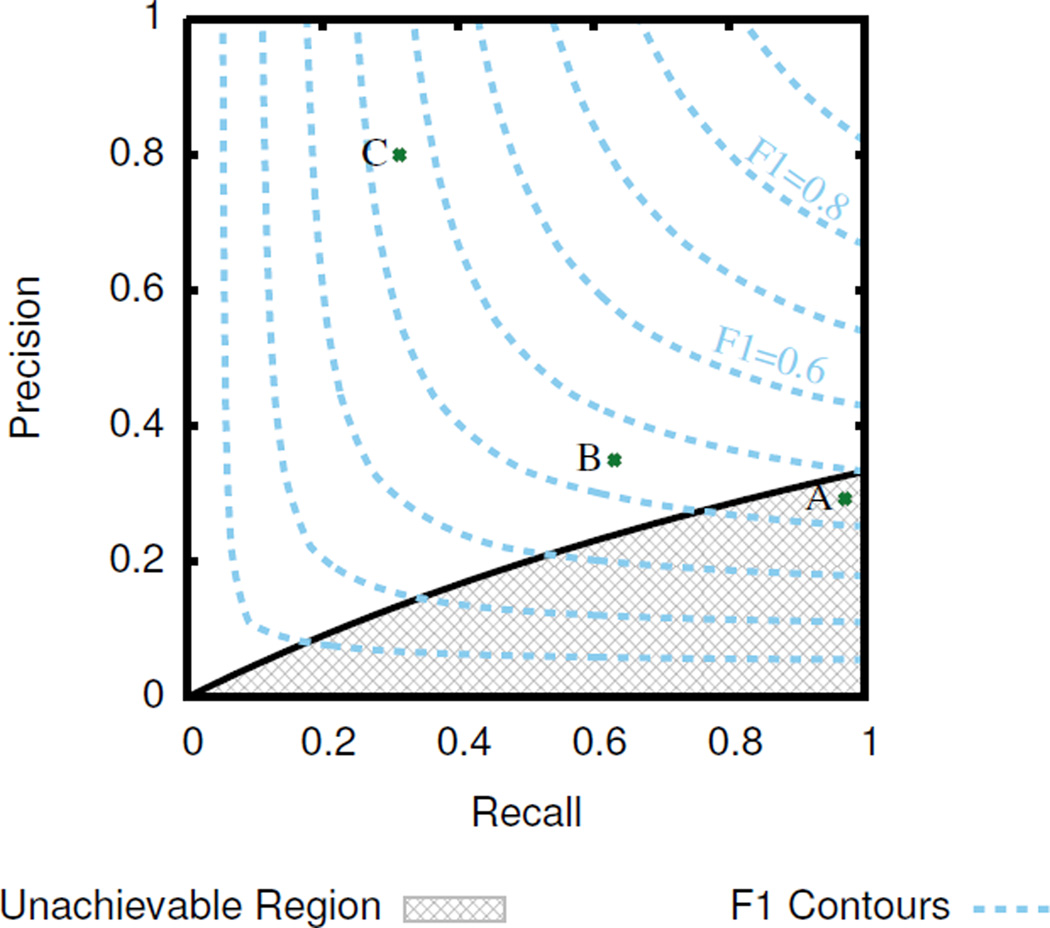

Figure 4.

Contours of F1 score in PR space with the minimum PR curve and unachievable region for π = 0.33. The points A, B, and C all have F1 = 0.45, but lead to substantially different practical interpretations.

While the unachievable region of PR space does not put any bounds on F1 score based on skew, there is still a subtle interaction between skew and F1. Since F1 combines precision and recall into a single score, it necessarily loses information. One aspect of this information loss is that PR points with the same F1 score can have vastly different relationships with the unachievable region. Consider points A, B, and C in Figure 4. All three have an F1 score of 0.45, but each has a very different interpretation if obtained from a data set with π = 0.33. Point A is unachievable and no valid confusion matrix for it exists. Point B is achievable, but is very near the minimum PR curve and is only marginally better than random guessing. Point C has reasonable performance representing good precision at modest recall.

While losing information is inevitable with a summary like F1, the different interpretations arise partly because F1 treats recall and precision interchangeably. Furthermore, this is not unique to β = 1. While Fβ changes the relative importance, the assumption remains that precision and recall, appropriately scaled by β, are equivalent for assessing performance. Our results on the unachievable region show this is problematic as recall and precision have fundamentally different properties. Every recall has a minimum precision, while there is a maximum recall for low precision, and no constraints for most levels of precision.

While a modified F1 score that is sensitive to the unachievable region would be useful, initial work suggests an ideal solution may not exist. Consider three simple requirements for a modified F1 score, f′:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Eq. (3) ensures f′ = 0 if the PR point is on the minimum PR curve and Eqs. (4) and (5) capture the expectation that an increase in precision or recall while the other is constant should always increase f′. However, these three properties are impossible to satisfy because they require 0 = f′(0, 0) < f′(0, π) < f′(1, π) = 0. Relaxing Eqs. (4) and (5) to ≤ makes it possible to construct an f′ that satisfies the requirements but implies f′ (r, p) = 0 if p ≤ π. This seems unsatisfactory because it ignores all distinctions once the performance is worse than random guessing. One modified F1 score that satisfies the relaxed requirements would assign 0 to any PR point worse than random guessing and use the harmonic mean of recall and (precision normalized to random guessing) otherwise.

Ultimately, while F1 score or a modified F1 score can be extremely useful, nuanced analyses must never overlook that it is a summary metric, and vital information for interpreting a model’s performance may be lost in the summarizing.

5. Conclusion

We demonstrate that a region of precision-recall space is unachievable for any particular ratio of positive to negative examples. With the precise characterization of this unachievable region given in Theorems 1 and 2, we further the understanding of the effects of downsampling and the impact of the minimum PR curve on F measure and score aggregation.

Figure 2.

Minimum PR curves for several values of π.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jude Shavlik and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions, and Stanley Kok for providing the LSM algorithm results. We gratefully acknowledge our funding support. KB is funded by NIH 5T15LM007359. VC by the ERDF through the Progr. COMPETE, the Portuguese Gov. through FCT, proj. HORUS ref. PTDC/EIA-EIA/100897/2008, and the EU Sev. Fram. Progr. FP7/2007-2013 under grant aggrn 288147. JD by the Research Fund K.U. Leuven (CREA/11/015 and OT/11/051), EU FP7 Marie Curie Career Integration Grant (#294068), and FWO-Vlaanderen (G.0356.12). DP by NIGMS grant R01GM097618-01, NLM grant R01LM011028-01, NIEHS grant 5R01ES017400-03 and the UW Carbone Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Appearing in Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Machine Learning, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, 2012.

To be strictly true in ROC space, fractional counts for tp, fp, fn, tn must be allowed. The fractional counts can be considered integer counts in an expanded data set.

Contributor Information

Kendrick Boyd, Email: boyd@cs.wisc.edu, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 1300 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706 USA.

Vítor Santos Costa, Email: vsc@dcc.fc.up.pt, CRACS INESC-TEC & FCUP, Rua do Campo Alegre, 1021/1055, 4169 - 007 PORTO, Portugal.

Jesse Davis, Email: jesse.davis@cs.kuleuven.be, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200a, Heverlee 3001, Belgium.

C. David Page, Email: page@biostat.wisc.edu, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 1300 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706 USA.

References

- Boyd K, Costa V, Davis J, Page CD. Technical Report TR1772. Madison: Department of Computer Sciences, University of Wisconsin; 2012. Unachievable region in precision-recall space and its effect on empirical evaluation. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clémençon S, Vayatis N. Nonparametric estimation of the precision-recall curve. ICML 2009. 2009:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Goadrich M. The relationship between precision-recall and ROC curves. ICML 2006. 2006:233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Burnside E, Dutra I, Page CD, Costa V. Machine Learning: ECML 2005. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2005. An integrated approach to learning Bayesian networks of rules; pp. 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Forman G, Scholz M. Apples-to-apples in cross-validation studies: pitfalls in classifier performance measurement. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2010 Nov;12:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Goadrich M, Oliphant L, Shavlik J. Gleaner: creating ensembles of first-order clauses to improve recall-precision curves. Machine Learning. 2006 Sep;64:231–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Lim E, Krishnan R. Predicting outcome for collaborative featured article nomination in wikipedia; International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kok S, Domingos P. Learning Markov logic networks using structural motifs. ICML 2010. 2010:551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Ling X, Weld DS. Temporal information extraction. AAAI 2010. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Shriberg E. Comparing evaluation metrics for sentence boundary detection. ICASSP 2007. 2007;ume 4:185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Manning CD, Raghavan P, Schtze H. Introduction to Information Retrieval. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalkova L, Mooney RJ. Bottom-up learning of Markov logic network structure. ICML 2007. 2007:625–632. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan S, Khot T, Kersting K, Gutmann B, Shavlik J. Gradient-based boosting for statistical relational learning: The relational dependency network case. Machine Learning. 2011 May;86(1):25–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenburg S, Zien A, Rätsch G. ARTS: accurate recognition of transcription starts in human. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2006 Jul;22(14):e472–e480. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov R, Tenenbaum J. Modelling relational data using Bayesian clustered tensor factorization. Neural Information Processing Systems. 2010;23 [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Zhang Y, Chawla NV, Krasser S. SVMs modeling for highly imbalanced classification. Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B: Cybernetics, IEEE Transactions on. 2009 Feb;39(1):281–288. doi: 10.1109/TSMCB.2008.2002909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Finley T, Radlinski F, Joachims T. A support vector method for optimizing average precision. SIGIR 2007. 2007:271–278. [Google Scholar]