Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The Departments of Surgery at the University of North Carolina (UNC) and Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) in Lilongwe, Malawi, formed a partnership of service, training, and research in 2008. We report a case of recurrent pancreatitis leading to pancreatic necrosis treated at KCH.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 42 year-old male presented to KCH with his fourth episode of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. He had tachycardia, guarding, rebound tenderness, and free fluid on abdominal ultrasonography. He underwent laparotomy and had fat saponification with pancreatic necrosis. A large drain was placed, he was given antibiotics, and he recovered. He had normal lipids, no gallstones, and did not consume alcohol. He was encouraged to seek further evaluation with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or computed tomography in South Africa, however this was prohibitively expensive.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the limitations that are often faced by surgeons visiting developing countries. What we consider standard resources and treatment algorithms in managing necrotizing pancreatitis in developed countries (such as serum lipase and percutaneous interventions) were not available.

CONCLUSION

Visiting surgeons and trainees must be both familiar with local resource limitations and aware of the implications of such limitations on patient care. To support training and promote advances in health care, local surgeons and trainees should understand optimal treatment strategies regardless of their particular resource limitations. North–South partnerships are an excellent means to uphold our professional obligation to humanity, promote health care as a right, and shape the future of health care in developing countries.

Keywords: Pancreatitis, Developing countries, Malawi, Africa below the Sahara

1. Introduction

Pancreatitis is an inflammation of the pancreas that can be acute or chronic. Typical findings include nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain that often radiates to the back.1 The most common etiologies in developed countries are alcohol consumption, gallstones and idiopathic.2 Other etiologies include auto-immune, anatomic (pancreas divisum) and drug-induced. In Malawi gallstones are rare and more common etiologies include alcohol consumption and medications (such as isoniazid and stavudine).3,4 A distinct entity, tropical pancreatitis, is seen among young individuals during prolonged periods of decreased food intake particularly in warm climates.5 Acute pancreatitis can be recurrent. Typically chronic pancreatitis is more indolent course that occurs after multiple attacks of acute pancreatitis, and often leads to pancreatic insufficiency. Necrotizing pancreatitis is a severe form of acute pancreatitis that results from tissue ischaemia and necrosis, often leads to serious infections and has a high mortality (up to 25%).6 We utilize the following case of acute necrotizing pancreatitis as a means of exploring the opportunities and challenges of a North–South health partnership.

2. Presentation of the case

A 42 year-old male presented to Kamuzu Central Hospital for evaluation of worsening abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting starting 3 days prior to presentation. On admission, his history was remarkable for four similar prior episodes over the previous five years that lasted between 3 and 5 days. He denied any constipation, obstipation or associated hematemesis, fevers, chills or urinary symptoms. During the first episode five years ago, he was evaluated at an outlying health centre and diagnosed with peptic ulcer disease and was managed with omeprazole intermittently. His past medical and surgical history was otherwise negative and non-contributory and he had no allergies. He denied alcohol intake or tobacco use. His HIV serostatus was negative approximately one year prior to presentation.

On examination he was afebrile, with a heart rate of 120 beats/min, blood pressure 135/78 mmHg and respiratory rate of 22/min. Abdominal examination revealed mild distension with generalized guarding and marked rebound tenderness in the epigastrium. There were no palpable masses and bowel sounds were absent. Full blood count, serum chemistry (including amylase and lipase), and computed tomography were unavailable at KCH. Erect and supine abdominal and chest radiographs were normal. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed free fluid throughout the abdomen and pelvis.

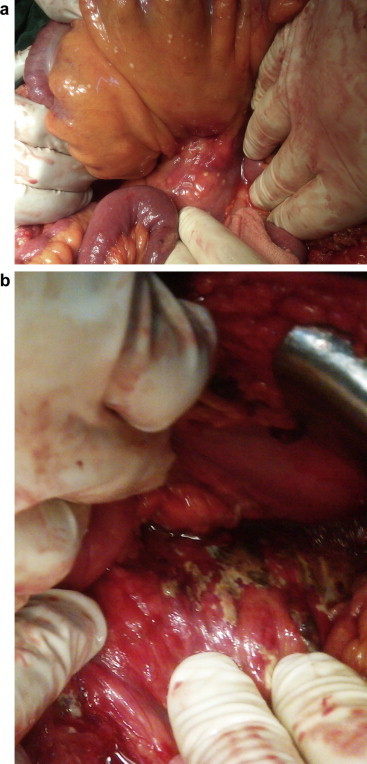

Based on his vital signs and physical examination, he was resuscitated with intravenous fluids and taken urgently to theatre for an exploratory laparotomy with a provisional diagnosis of a perforated peptic ulcer and differential diagnoses of ruptured appendicitis, midgut volvulus, pancreatitis and typhoid perforation. The peritoneum was accessed via a vertical midline incision. Upon entering the peritoneal cavity, approximately 2 L of clear reddish brown fluid was encountered and evacuated. The anterior stomach, duodenum, gallbladder, liver, small bowel, colon and appendix were normal. Palpation through the stomach and transverse mesocolon noted a firm midline mass-like structure. There were no obvious gallstones on palpation. There were multiple sub-centimetre white nodules on the transverse mesocolon (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative photographs showing the transverse mesocolon (a) and the pancreas (b).

As the source of his pathology was not yet diagnosed, the lesser sac was entered between the transverse colon and stomach to evaluate for posterior gastric or pancreatic pathology. There was significant inflammation between the stomach, transverse mesocolon and pancreas making this exposure challenging. However upon releasing the scarred inflamed tissue planes it was evident the pancreas was the source (Fig. 1B). A large drain (24 french) was inserted through the right mid-abdomen overlying the pancreas and placed to gravity drainage. Biopsies of both the whitish nodules and the inflamed pancreatic tissue were obtained for tuberculosis testing which was negative by acid-fast bacillus smear and nucleic acid amplification.7,8 After irrigation, the abdomen was closed and he was transferred to the surgical high dependency unit and managed with a regimen of nil per os, intravenous fluids, nasogastric decompression and intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole). He recovered uneventfully and was discharged on post op day #5 with a 10 day course day of oral antibiotics (cephalexin and metronidazole) and instructions to empty and record his drain output daily. He was also asked to obtain a fasting lipid profile including triglycerides.

He returned one week later for review with a normal lipid profile. His drain initially put out 100 mL per day of serosanguinous fluid but the output tapered down to 5 mL per day of serous yellow fluid for two days prior and was hence removed. He denied any fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain. His abdominal skin sutures were removed. He finished his course of antibiotics and remained asymptomatic. He was counselled to take smaller more frequent meals, stay hydrated, and return to the hospital should his symptoms return. He was also counselled that if he developed early satiety or abdominal pain he may require a CT scan to evaluate for a pancreatic pseudocyst and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

3. Discussion

This case is a typical presentation of recurrent acute pancreatitis with a severe attack leading to pancreatic necrosis. The diagnostic and treatment modalities employed in this case are well below standard of care in developed countries. Usually the diagnosis of pancreatitis is confirmed by an elevated lipase (greater than three times normal), but this study is not available at KCH.9 Computed tomography was also not available, despite its near universal application in developed countries; evaluating for pseudocysts, ductal dilation, pancreatic necrosis, or peri-pancreatic gas is considered essential. When available percutaneous intervention is preferred as an initial management strategy.10 However at KCH this is also not available therefore the treatment was surgical with irrigation of the abdomen, debridement and drainage.

The rapidly growing interest in developing North–South academic partnerships provides an unparalleled opportunity to shape the future of health care in developing countries.11 Visiting surgeons must be not only familiar with local resources, but comfortable functioning with much less than accustomed to. Recognizing these limitations in such areas as laboratory diagnostics, drug formularies, radiologic imaging and interventions, nursing support, critical care services, surgical adjuncts (such as stapler devices and advanced tissue dissection and coagulation devices), and operating room capacity are essential to having a productive and ultimately also a rewarding experience. These limitations also provide the opportunity for a professionally challenging and satisfying experience; the lack of diagnostics and non-surgical interventions often means that surgically managed problems are best managed in the operating theatre.

While not necessary to their preparation as competent surgeons, we strongly believe that local trainees still benefit from the interaction with visiting surgeons. As mentioned previously, trainees gain an awareness of diagnostic and treatment modalities that may at some point be available in-country. For example, the work-up of many surgical patients often includes computed tomography, which until very recently was not available at Kamuzu Central Hospital. However, since the partnership was established in 2008, at morning report visiting surgeons frequently discussed the theoretic application and benefit of computed tomography. An additional benefit to trainees is the exposure to the academic model of Western institutions; such a perspective often encourages local trainees to challenge dogma and develop hypothesis-based research that is culturally and epidemiologically relevant. For example, a cancer registry recently started by the UNC–KCH partnership served as a catalyst for several local trainee initiated projects related to the young age and unique disease patterns of Malawian cancer patients.12,13

Embracing health care as a right requires us to view this without international boundaries or prioritizing personal gain. Our profession must accept the responsibility that comes with such an assertion of health care as a right; accepting a global veil of ignorance is mandatory. The hippocratic oath states that we physicians may enjoy a life and art that is “respected by all humanity and in all times.” It follows that we also owe our respect to all of humanity, regardless of international boundaries. Similar to its challenge of Westphalian sovereignty, globalization should also question the traditional roles of physicians who are comfortable functioning within a domestic structure that for the most part lacks any consideration for greater humanity.14 We encourage our colleagues to recognize the mutually beneficial aspects of such North–South partnerships. Most importantly, pursuing such endeavours is an ideal way to both uphold our professional commitment and to take responsibility for claiming health care as a basic human right.

4. Conclusion

Pancreatitis ranges from mild acute attacks to fulminant pancreatic necrosis. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment is necessary to achieve better outcomes for these patients. This case provides an example of how to manage such a case in a resource-poor environment. The case also illustrates the benefits of a North–South partnership founded on education, service, and research. We encourage other institutions to develop and strengthen similar relationships.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fogarty International Centre of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01TW009486. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

The conception and designing of the study were completed by Samuel and Ludzu. Acquisition of clinical report was done by Samuel and Ludzu. Manuscript was drafted and revised by all the authors. Administrative, technical, and material support were given by all the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa, the Malawi College of Medicine and the Department of Surgery at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital for technical support and advice regarding development of the General Surgery training programme at Kamuzu Central Hospital.

We also thank Johnson and Johnson, the NC Jaycee Burn Centre and the University of North Carolina Department of Surgery for supporting the partnership between the University of North Carolina and Kamuzu Central Hospital Departments of Surgery, and UNC Project for administrative support and providing the Tuberculosis testing.

This work was supported by the Fogarty International Centre of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01TW009486. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Bradley E.L., 3rd A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, vol. 128(5); Atlanta, GA, September 11–13, 1992. Arch. Surg.; 1993. pp. 586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang G.J., Gao C.F., Wei D., Wang C., Ding S.Q. Acute pancreatitis: etiology common pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(March (12)):1427–1430. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey A.S., Surana A. Isoniazid-induced recurrent acute pancreatitis. Trop Doct. 2011;41(October (4)):249–250. doi: 10.1258/td.2011.110127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Oosterhout J.J., Mallewa J., Kaunda S., Chagoma N., Njalale Y., Kampira E. Stavudine toxicity in adult longer-term ART patients in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e42029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nwokolo C., Oli J. Pathogenesis of juvenile tropical pancreatitis syndrome. Lancet. 1980;1(March (8166)):456–459. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchler M.W., Gloor B., Muller C.A., Friess H., Seiler C.A., Uhl W. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis: treatment strategy according to the status of infection. Ann Surg. 2000;232(November (5)):619–626. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marlowe E.M., Novak-Weekley S.M., Cumpio J., Sharp S.E., Momeny M.A., Babst A. Evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF assay for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(April (4)):1621–1623. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02214-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yajko D.M., Nassos P.S., Sanders C.A., Madej J.J., Hadley W.K. High predictive value of the acid-fast smear for Mycobacterium tuberculosis despite the high prevalence of Mycobacterium avium complex in respiratory specimens. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19(August (2)):334–336. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gumaste V.V., Roditis N., Mehta D., Dave P.B. Serum lipase levels in nonpancreatic abdominal pain versus acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(December (12)):2051–2055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Besselink M.G., van Santvoort H.C., Nieuwenhuijs V.B., Boermeester M.A., Bollen T.L., Buskens E. Minimally invasive ‘step-up approach’ versus maximal necrosectomy in patients with acute necrotising pancreatitis (PANTER trial): design and rationale of a randomised controlled multicenter trial [ISRCTN13975868] BMC Surg. 2006;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riviello R., Ozgediz D., Hsia R.Y., Azzie G., Newton M., Tarpley J. Role of collaborative academic partnerships in surgical training, education, and provision. World J Surg. 2010;34(March (3)):459–465. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0360-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopal S., Krysiak R., Liomba G. Building a pathology laboratory in Malawi. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(April (4)):291–292. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gopal S., Kysiak R., Liomba G., Horner M., Shores C., Alide N. Early experience after developing a pathology laboratory in Malawi, with emphasis on cancer diagnoses. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e70361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benatar S.R., Daar A.S., Singer P.A. Global health ethics: the rationale for mutual caring. Int Aff. 2003;79(July (4)):112. [Google Scholar]