Abstract

Oxazaphosphorines, with the most representative members including cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and trofosfamide, constitute a class of alkylating agents that have a broad spectrum of anticancer activity against many malignant ailments including both solid tumors such as breast cancer and hematological malignancies such as leukemia and lymphoma. Most oxazaphosphorines are prodrugs that require hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes to generate active alkylating moieties before manifesting their chemotherapeutic effects. Meanwhile, oxazaphosphorines can also be transformed into non-therapeutic byproducts by various drug-metabolizing enzymes. Clinically, oxazaphosphorines are often administered in combination with other chemotherapeutics in adjuvant treatments. As such, the therapeutic efficacy, off-target toxicity, and unintentional drug-drug interactions of oxazaphosphorines have been long-lasting clinical concerns and heightened focuses of scientific literatures. Recent evidence suggests that xenobiotic receptors may play important roles in regulating the metabolism and clearance of oxazaphosphorines. Drugs as modulators of xenobiotic receptors can affect the therapeutic efficacy, cytotoxicity, and pharmacokinetics of coadministered oxazaphosphorines, providing a new molecular mechanism of drug-drug interactions. Here, we review current advances regarding the influence of xenobiotic receptors, particularly, the constitutive androstane receptor, the pregnane X receptor and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, on the bioactivation and detoxification of oxazaphosphorines, with a focus on cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide.

Keywords: oxazaphosphorine, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, CAR, PXR, CYP2B6

1. Introduction

Oxazaphosphorines are a class of bi-functional alkylating agents that have been extensively investigated in the past 50 years for their anticancer and immune-regulating activities, with the most successful representatives including cyclophosphamide (CPA), ifosfamide (IFO), and to a lesser extent trofosfamide 1; 2; 3; 4. Most oxazaphosphorines are designed prodrugs, which require cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme-mediated bioactivation to generate highly reactive alkylating nitrogen mustards that exert their chemotherapeutic effects by attacking specific nucleophilic groups of DNA molecules in target cancer cells 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10. CPA is the first oxazaphosphorine agent that achieved great success in its clinical application in many cancer patients 11; 12; 13. Although CPA has been clinically available for over a half century, it continues to be amongst the front-line choices of chemotherapy for solid tumors, such as breast cancer, for which it is used as an important component of the CPA-methotrexate-fluorouracil (CMF) regimen 14; 15, and hematopoietic malignancies, such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma, for which it is applied as a critical constituent of the rituximab-CPA-doxorubicin-vincristine-prednisone (R-CHOP) multidrug regimen 16; 17. Additionally, CPA has also been used at higher doses in the treatment of aplastic anemia and leukemia prior to bone marrow transplantation and as a therapeutic immunosuppressor for several autoimmune disorders 18; 19.

IFO, the second anticancer drug in the oxazaphosphorine class, was introduced to clinics in the early 1970s 4; 20. Developed as an analogue of CPA, IFO only differs chemically from CPA by one chloroethyl group transpositioned from the mustard nitrogen to the ring nitrogen 21. Like CPA, IFO also requires CYP-mediated metabolism to produce active alkylating moieties before manifesting its antitumor effects 22; 23. Clinically, IFO has been used in young adult and pediatric tumors along with other chemotherapeutics in adjuvant treatment. In a number of malignant diseases, IFO exhibits a higher therapeutic response rate, with less myelosuppression, in comparison with its parent analogue CPA 24; 25. Trofosfamide is another derivative of CPA and an orally administered oxazaphosphorine prodrug with high bioavailability 26. As a congener of CPA and IFO, the antitumor cytotoxicity of trofosfamide also relies on its metabolic activation by “ring” oxidation, using the hepatic mixed-function oxidase system 27; 28. Trofosfamide is often used clinically in adult soft tissue sarcomas and non-Hodgkin lymphomas with relatively low toxicity profiles 29; 30; 31.

In addition to these traditional oxazaphosphorines, several new analogues of CPA and IFO such as mafosfamide and glufosfamide have been designed, aiming to achieve increased therapeutic selectivity and reduced off-target toxicity, in comparison with their ascendants 32; 33. Unlike traditional oxazaphosphorines, mafosfamide and glufosfamide do not require hepatic oxidative enzyme-mediated bioactivation. For instance, mafosfamide is a 4-thioethane sulfonic acid salt of 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide (4-OH–CPA), a key bioactive intermediate metabolite of CPA 10; 34; while glufosfamide is a glucose conjugate of ifosfamide, in which isophosphoramide mustard, the bioactive alkylating metabolite of ifosfamide, is covalently linked to β-D-glucose 35; 36. At present, several Phase I studies have shown favorable outcomes from intrathecal administration of mafosfamide in the treatment of meningeal malignancies, although further comprehensive clinical evaluation is needed 37; 38. In the case of glufosfamide, the development of this oxazaphosphorine agent was based on the rationale that cancer cells are active in importing and utilizing glucose. Thus, the differential expression of transmembrane glucose transporters between cancer and normal cells accounts for the target selectivity of glufosfamide 39; 40. Recent clinical trials revealed beneficial effects of utilizing glufosfamide in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, as well as head and neck squamous cell carcinoma 41; 42; 43. Together, these promising anticancer activities of mafosfamide and glufosfamide indicate that new generation of oxazaphosphorine agents, with better target selectivity and less unwanted cytotoxicity, could be clinically available in the near future.

The journey of our understanding of the mechanisms underlying oxazaphosphorine action started with the development of CPA. After many years of intensive investigation, although a number of new oxazaphosphorine derivatives displayed promising therapeutic features, currently, CPA and IFO remain to be the most successful and widely used oxazaphosphorines in the treatment of an array of various malignancies. As aforementioned, CPA and IFO are prodrugs requiring metabolic activation by hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes. The expression and functional perturbation of these enzymes can dramatically influence the metabolism, clearance, and pharmacokinetics of these oxazaphosphorines. Recently, accumulating evidence suggests that nuclear receptors, in particular, a group of so-called “xenobiotic receptors”, are the primary regulators governing the transcription of most hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters 44; 45; 46. Drugs as modulators of xenobiotic receptors can affect the metabolism rate and pharmacokinetics of coadministered oxazaphosphorines, and dictate their therapeutic efficacy and toxicity, accordingly. The current review tends to highlight the recent advances in elucidating the roles of xenobiotic receptors in mediating the bioactivation and deactivation of oxazaphosphorines with the focus on the roles of the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR, NR1I3), the pregnane X receptor (PXR, NR1I2), and the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) on metabolism and clearance of CPA and IFO. This review however is by no means a comprehensive coverage of all findings of oxazaphosphorine research.

2. Metabolism and Transport of Oxazaphosphorines

2.1. Cytochrome P450

Prototypical oxazaphosphorine cytostatics such as CPA and IFO are chemically and pharmacologically inactive transport forms of alkylating nitrogen mustards that are biotransformed to their active forms predominantly in the liver 47; 48. As one of the key mechanisms of action, hepatic metabolism of CPA, has been extensively studied during the past several decades, utilizing human and animal liver microsomes, primary hepatocytes, recombinant CYP enzymes, CYP-selective chemical and antibody inhibitors, as well as whole animal models 48; 49; 50. Upon administration, CPA undergoes hepatic oxidation to form the pharmacologically active intermediate metabolite 4-OH-CPA, which enters blood circulation and is transported to target tissues by binding to erythrocytes 51; 52; 53; 54. 4-OH-CPA is further tautomerized to aldophosphamide, followed by spontaneous β-elimination to release the phosphoramide mustard as the final DNA-cross-linking metabolite 10; 55. Notably, hydroxylation of CPA at the 4-carbon position is the rate limiting step of its bioactivation, and blood concentration of 4-OH-CPA has often been used as a biomarker monitoring the efficacy of CPA therapeutics 56; 57; 58. Multiple CYP isozymes are involved in the hydroxylation of CPA, including CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9, CYP2C18, and CYP2C19 49; 50; 59; 60, with CYP2B6 being the primary player, which contributes approximately 45% of CPA bioactivation 48; 49; 50. To a lesser extent, CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 also contribute around 25% and 12% of CPA 4-hydroxylation, respectively 49; 50. Alternatively, CPA is subject to significant side-chain oxidation, primarily N-dechloroethylation, by a number of CYPs to generate the inactive dechloroethyl-CPA and the toxic byproduct chloroacetaldehyde (CAA) 27; 49; 58; 60 (Figure 1). The predominant CYP enzyme responsible for the N-dechloroethylation of CPA is CYP3A4, which was reported to be responsible for up to 95% of this reaction, followed by CYP3A7 and CYP3A5 27; 49; 53; 60. On the other hand, CYP2B6 only provides negligible contribution to this non-therapeutic biotransformation of CPA 60.

Figure 1. Schematic summary of cyclophosphamide (CPA) and ifosfamide (IFO) metabolism.

The prodrugs CPA and IFO are biotransformed through a group of CYP and non-CYP drug-metabolizing enzymes to form their therapeutically active DNA-crosslinking mustards, as well as non-therapeutic metabolic byproducts (modified from Wang et al., 2011, Pharmaceutical Res. 120).

Metabolism of IFO shares a generally CYP-based pathway in common with that of CPA, but exhibits differential CYP affinity and metabolism rates 23; 34. Akin to CPA, IFO is bioactivated by CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 to form the 4-hydroxy-ifosfamide (4-OH-IFO), which subsequently goes through a series of biochemical reactions to yield the ultimate therapeutic alkylating agent, ifosfamide mustard 48; 61. More detailed characterization, however, revealed that CYP3A4 plays a major role in the 4-hydroxylation of IFO with CYP2B6 as a supplementary isozyme 56; 62. Moreover, these two CYP enzymes also control the N-dechloroethylation of IFO forming the neurotoxic CAA 49; 60, with CYP3A4 contributing approximately 70% of liver microsomal CAA formation and CYP2B6 accounting for roughly 25% 34; 49. Additionally, CYP3A5 was also reported to be involved in the dechloroethylation of IFO. Polymorphic mutations of CYP3A5 can affect the rate of CAA formation as well 63.

In comparing the biotransformation of CPA and IFO, only 10% of CPA is subject to N-dechloroethylation, whereas approximately 25%-60% of IFO undergo this metabolic pathway, generating more toxic byproducts 58; 64; 65. This rather distinct profile of metabolism also contributes to the clinically observed side-effect, in which CAA-mediated neurotoxicity occurs in ~20% of IFO-treated patients, while happens quite rare in CPA-treated patients 66; 67. Importantly, CYP enzymes are involved differentially in the biotransformation of these oxazaphosphorines; for instance, CYP2B6 selectively activates CPA over IFO and only exhibits a negligible effect on CPA-N-dechloroethylation. Therefore, it might be possible to design novel CPA-based therapeutic regimens by modulating these metabolic pathways to achieve greater bioactivation without concurrent augmentation of unwanted cytotoxicity.

2.2. Other drug-metabolizing enzymes

Following CYP-mediated 4-hydroxylation, both CPA and IFO can be further activated to their corresponding therapeutic mustards or inactivated to different byproducts through sequential metabolic processes mediated by other non-CYP drug-metabolizing enzymes 26; 34. First, 4-OH-CPA quickly reaches equilibrium with its acyclic form, aldophosphamide, which can be spontaneously decomposed through β-elimination to form the ultimate active alkylating product phosphoramide mustard and a urotoxic byproduct acrolein, which is commonly associated with clinically important hemorrhagic cystitis 3; 10; 34. Intracellular phosphoramide mustard then attacks host DNA to exert expected cytotoxicity. Alternatively, phosphoramide mustard can undergo detoxification by glutathione S-transferase (GST)-mediated conjugation, hydrolysis of the chloroethyl side chain to form alcohols, or cleavage of the phosphorus-nitrogen bond to release 3-(2-chloroethyl)-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (CNM), which are all metabolic byproducts without antitumor activity 68. The acrolein, meanwhile, is converted to acrylic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH), ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1 69; 70. An important detoxification pathway for 4-OH-CPA is the conversion of its tautomer, aldophosphamide, to the less toxic carboxyphosphamide (CEPM), which represents a major stable non-therapeutic metabolite of CPA found in clinical samples 71; 72. This oxidative reaction is primarily catalyzed by ALDH1A1 73; 74, and to a lesser extent by ALDH3A1 and ALDH5A1 75. Alternatively, aldophosphamide can be oxidized to form alcophosphamide by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldo-keto reductase (AKR1) 76 (Figure 1). An additional detoxification pathway occurs through reversible dehydration to form imminocyclophosphamide, which is further conjugated with glutathione mediated by GSTA1, GSTA2, GSTM1, and GSTP1, and eventually generates the nontoxic 4-glutathionylcyclophosphamide 77; 78.

The major difference regarding the metabolism of CPA and IFO happens in the CYP-mediated 4-hydroxylation and N-dechloroethylation. Metabolic destinations of these oxazaphosphorines thereafter are highly comparable. As with 4-OH-CPA, 4-OH-IFO exists in equilibrium with its tautomer aldoifosfamide, which decomposes through β-elimination to yield ifosforamide mustard and acrolein. Ifosforamide mustard is also subject to further degradation, forming the inactive metabolite CNM and chloroethylamine 79. Similarly, 4-OH-IFO can also be biotransformed to carboxyifosfamide by ALDH1A1, to 4-keto-IFO by AKR1, or to alcoifosfamide by ADH and AKR1 23; 34. Glutathione conjugation represents another important detoxification mechanism of ifosforamide mustard 80.

Collectively, it is evident now that both CYP and non-CYP drug-metabolizing enzymes can contribute to the bioactivation and detoxification of CPA and IFO. Although liver contains the most abundant drug-metabolizing enzymes and plays predominant roles in the biotransformation of oxazaphosphorines, extrahepatic tissue-specific expression of these enzymes also contribute to the targeted “selective cytotoxicity” which is one of the leading motive in developing safe and effective chemotherapeutics.

2.3. Drug transporters

It is believed that all oxazaphosphorine prodrugs are highly hydrophilic and thus are not easily diffused across cell membranes. Mounting clinical and experimental evidence, however, agreed that both CPA and IFO can be readily administered orally or intravenously with high bioavailability and decent intracellular concentrations 81; 82; 83. These phenomena suggest that active uptake transporters may contribute to the absorption of these oxazaphosphorines though direct scientific support is limited thus far. Conversely, the circular proactive metabolites of these oxazaphosphorines, 4-OH-CPA, aldophosphamide and 4-OH-IFO, can easily cross the lipid bilayer membranes of many cells through passive diffusion 34. In contrast to uptake, more research efforts have been centered on the efflux transportation of these alkylating agents from cancer cells, which is pivotal in multidrug resistance of cancer chemotherapy. In this regard, a number of ATP-binding cassette transporters have been identified as transmembrane modulators associated with exporting CPA, IFO, and their metabolites 34; 84; 85.

In vitro studies, utilizing HepG2 cells stably transfected with multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4, ABCC4) expression vector, have clearly established that CPA and IFO are substrates of this efflux transporter. Overexpression of MRP4 in HepG2 cells led to increased resistance to CPA- and IFO-induced cytotoxicity, while inhibition of this transporter by diclofenac or celecoxib, two known inhibitors of MRP4, significantly sensitized the MRP4-HepG2 cells to CPA and IFO 85; 86. Notably, glutathione, the most abundant cellular redox molecule, plays an important role in the function of MRP4 and depletion of intracellular glutathione can significantly affect the export of cAMP by MRP4 87; 88. Since glutathione is pivotal in detoxification of phosphamide and ifosforamide mustards, it was speculated that MRP4-mediated resistance to CPA and IFO might be glutathione-dependent. Indeed, addition of buthionine sulfoximine, a glutathione synthesis inhibitor, considerably reversed MRP4-mediated resistance to CPA and IFO in MRP4-HepG2 cells 86.

The multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2, ABCC2) has been reported to export a detoxified CPA metabolite, 4-glutathionylcyclophosphamide, from hepatocytes into the bile in rats; this biliary excretion appears to compete with the bioactivation pathway that generates the active alkylating agent 89. In addition, clinical studies have shown that multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1, ABCC1) and the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP, ABCG2) are involved in the resistance to chemotherapy in breast cancer patients receiving CMF regimen 90; 91; 92. However, whether CPA and/or its metabolites are substrates of BCRP and/or MRP1 requires further investigation, given that methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil in the CMF regimen are known substrates of BCRP 93; 94.

MRP1, MRP2, and BCRP are all expressed in the apical (canalicular) membrane of hepatocytes and are in charge of hepatic biliary excretion of many drugs and endobiotics into the bile. Conversely, MRP4 is localized in the basolateral (sinusoidal) membrane of hepatocytes and in the apical (luminal) membrane of kidney proximal tubules 95. The fact that approximately 70% of CPA is excreted in urine and only a small portion through the bile, may positively reflect the importance of MRP4 in CPA transportation 23; 96.

3. Xenobiotic Receptor and Oxazaphosphorine Metabolism

It is evident that the oxazaphosphorine type of alkylating prodrugs require hepatic biotransformation mediated by many drug-metabolizing enzymes to produce the ultimate DNA-alkylating mustards, with CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 predominantly governing the initial and rate-limiting step of their bioactivation. Although induction of CYP expression generally increases the elimination of drugs and leads to therapeutic failure, in the case of CPA and IFO, increasing CYP-mediated biotransformation can generate more cytotoxic intermediate metabolites with and without therapeutic potentials, which may lead to comprehensive prognostic outcomes. Many drugs and environmental chemicals can influence the expression of these CYP enzymes, which are transcriptionally regulated by a group of transcription factors termed xenobiotic receptors 97; 98; 99; 100. Unlike traditional endocrine hormone receptors, xenobiotic receptors, functioning as sensors of toxic byproducts derived from both endogenous and exogenous chemical breakdowns, are typically activated by abundant but low-affinity lipophilic molecules at rather high (micromolar) concentrations, without real endogenous ligands identified thus far 101; 102. Major xenobiotic receptors, including PXR, CAR and AhR, predominantly localized in the liver and intestines, have been documented as important xenobiotic sensors mediating the transcription of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters associated with the metabolism and clearance of oxazaphosphorines.

3.1. Pregnane X Receptor (PXR)

As one of the important components of the body’s adaptive defense mechanism against xenobiotics, PXR represents the most promiscuous xenosensor among all xenobiotic receptors and can be activated by a broad spectrum of ligands including prescription drugs, herbal medicines, environmental pollutants, and endobiotic derivatives 100; 103; 104; 105. The structural diversity of PXR ligands stems mainly from the unusually large, spherical, and flexible ligand binding pocket of the receptor 106; 107. Drug-mediated activation of PXR is associated with the inductive expression of many target genes including drug-metabolizing enzymes, such as CYP3A4, CYP2B6, CYP2Cs, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGT); and drug transporters, such as the multidrug resistance 1 (MDR1, ABCB1), and MRPs by recognizing and binding to specific xenobiotic response elements located in the promoters of these genes 45; 103; 108. Among others, CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 are highly inducible PXR target genes, which exhibit marked inter- and intra-individual variations in their expression 109; 110. As such, many clinically used drugs as PXR activators can influence the pharmacokinetics of CPA and IFO when coadministered in multidrug regimens. Additionally, accumulating evidence suggests that hepatic bioactivation of CPA and IFO is auto-inducible upon repeated application of these oxazaphosphorines 61; 111; 112.

Both CPA and IFO have been identified as human PXR agonists that contribute significantly to the observed auto-induction of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 by which their own metabolism and clearance are increased 100; 105; 113. In this process, CPA and IFO bind to the ligand binding domain of PXR that leads to the release of PXR-bound corepressors, such as the silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) and the nuclear receptor corepressor 1 (NCOR1), and the recruitment of its heterodimer partner, the retinoic X receptor (RXR), and other coactivators, such as steroid receptor 1 114. The PXR/RXR heterodimer directly interacts with specific promoter sequences of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 genes and stimulates their transcription 115. Additionally, Harmsen et al., recently reported that CPA and IFO can also induce the expression of MDR1 through PXR transactivation 116,117. Although MDR1 represents one of the major mechanisms associated with the multidrug resistant phenotype in response to many chemotherapeutics, CPA, IFO, and their proactive metabolites 4-OH-CPA and 4-OH-IFO, are not typical substrates of MDR1 34; thus, this induction may not directly affect the intracellular levels of these oxazaphosphorines and their active metabolites.

In addition to drug-induced activation, genetic polymorphisms of PXR may also affect the metabolism and pharmacokinetics of CPA and IFO in different patients. The presence of PXR variants was investigated by Hustert et al., in two Caucasian and African ethnic groups 118; three PXR protein variants (V140M, D163G, and A370T) were identified to be functionally associated with altered basal and/or induced transactivation of CYP3A promoter reporter genes. In a separate study, Lim et al., reported that a Q158K variant of PXR, found in Chinese population, impairs drug-mediated induction of CYP3A4 by altering ligand-dependent PXR interaction with the steroid receptor coactivator-1119. Although autoinduction of CYP3A4 by CPA and IFO was not directly investigated in these two studies, CPA and IFO are known activators of PXR, and inducers of CYP3A4 that enhance their own metabolism and clearance. Thus, these naturally occurring PXR genetic variants may play a role in the observed interindividual variability of CYP3A4 expression and therefore, influence the varied bioactivation of chemotherapeutic prodrugs including CPA and IFO.

3.2. Constitutive Androstane Receptor (CAR)

The constitutive androstane receptor, also denoted as the constitutively activated receptor (CAR; NR1I3), is the closest relative of PXR in the nuclear receptor superfamily and they share a panel of overlapping target genes, including a number of Phase I and II drug-metabolizing enzymes, as well as drug transporters that are involved in the metabolism and clearance of the oxazaphosphorines 45; 97. PXR and CAR also share many xenobiotic activators, such as the sedative phenobarbital, the anti-malaria artemisinin, the synthetic opioid methadone, as well as the oxazaphosphorine CPA but not IFO 120; 121; 122; 123; 124. As such, the extensive cross-talk between PXR and CAR may form a compensatory biological safety net that ensures comprehensive protection against various exogenous and endogenous chemicals. On the other hand, CAR also holds several unique features that separate itself from PXR and many other nuclear receptors. First, in line with its designated name, CAR is constitutively activated and spontaneously localized in the nucleus of nearly all immortalized cell lines independent of chemical stimulation 100; 110; 125. Secondly, unlike activation of PXR that is prototypically ligand-dependent, CAR could be transactivated by either direct binding to ligands such as the human CAR selective agonist 6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo-[2,1-b][1,3]thiazole-5-carbaldehyde-O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl) oxime (CITCO) or ligand-independent indirect mechanisms such as the prototypical CYP2B inducer, phenobarbital 126; 127. In fact, the majority of CAR activators identified thus far are actually phenobarbital-type of indirect activators without binding to the receptor. Last but not least, differing from the situation in immortalized cells, CAR is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes cultured in vitro or in the liver in vivo without activation and only translocates to the nucleus upon chemical stimulation 126; 128. Together, these features of CAR make the identification of its activators more challenging, particularly towards a high-throughput format in vitro. As a result, only a limited number of CAR activators thus far have been reported, in comparison to the numerous drugs and environmental toxicants documented as agonistic ligands of PXR.

Recent studies from our laboratory have shown that CPA but not IFO is a phenobarbital-like activator of CAR. Treatment of human primary hepatocytes at clinically relevant concentration of CPA but not IFO resulted in significant nuclear accumulation of adenovirus-expressing enhanced yellow fluorescent protein-tagged human CAR 120. Supported by additional in vitro data, it appears that while CPA can activate both PXR and CAR, IFO primarily transactivates PXR. Assuming this selective auto-induction also occurs in vivo, these findings may potentially be of clinical importance where drug-mediated manipulation of hCAR activity could alter the autoinduction and pharmacokinetics of selective oxazaphosphorines.

Similar to that of PXR, accumulating evidence suggests that both polymorphism and alternative splicing of human CAR play an important role in the modulation of its target gene expression 129; 130; 131. To date, approximately 30 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the human CAR gene have been identified, residing in the 5’-flanking regulatory regions, coding exons, and non-coding introns 132. Functional analysis of four SNPs, localized in the ligand binding domain of CAR, (His246Arg, Leu308Pro, Asn323Ser, and Val133Gly) revealed that His246Arg is associated with decreased CAR activation by CITCO, while Leu308Pro affect basal but not chemically stimulated CAR activation in cell-based reporter assays 131; 132. Recently, a number of naturally occurring alternative splicing variants of human CAR have been identified 133; 134; 135. Functional characterization of these spliced CAR transcripts revealed that some are associated with altered expression, cellular localization, and chemical response of the receptor 136; 137; 138; 139. For instance, unlike its constitutively active reference form, a splicing variant of human CAR, termed hCAR3, which contains an insertion of five amino acids (ALPYT) in the ligand-binding domain, exhibits low basal but xenobiotic-inducible activities in immortalized cell lines 136; 140. Another splicing variant hCAR2 with an insertion of four amino acids (SPTV) in a different region of the ligand-binding domain displays unique profile of xenobiotic-mediated activation that differs from the reference human CAR 141. Together, these genetic variations of human CAR may differentially affect the basal and inductive expression of many drug-metabolizing enzymes that eventually influence the disposition of CPA and IFO in clinical practice.

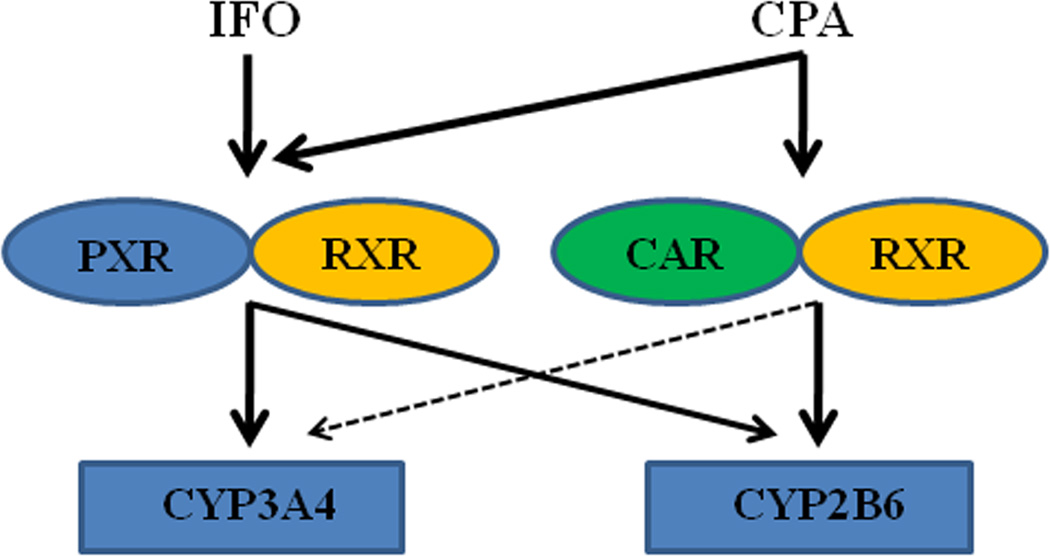

Notably, both human CAR and PXR also exhibit significant species-specific differences in comparison with their rodent counterparts 100; 125. In the context of “cross-talk” between these two receptors, while most data imply symmetrical cross-regulation of their target genes by rodent PXR and CAR, studies in our lab revealed that human CAR but not PXR asymmetrically cross-regulate the inductive expression of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4, in that human CAR exhibites preferential induction of CYP2B6 over CYP3A4, while human PXR mediates the expression of both genes with little discrimination 140; 142 (Figure 2). Given that CPA undergoes 4-hydroxylation to a therapeutically active metabolite primarily by CYP2B6 and N-dechloroethylation to a non-therapeutic neurotoxic metabolite by CYP3A4, the preference of hCAR for CYP2B6 over CYP3A4 may have clinical relevance in developing novel therapeutic regimens. Concurrent administration of CPA with a selective hCAR activator may facilitate the enhanced production of its beneficial metabolite without simultaneously increasing formation of its toxic metabolite.

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of cross-talk between PXR and CAR in the regulation of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 genes.

Activation of human CAR preferentially induces the expression of CYP2B6 over CYP3A4, while activation of human PXR increases the expression of both CYP genes with little discrimination. IFO is a selective activator of human PXR, while CPA can activate both receptors (modified from Faucette et al., 2006, JPET 142).

3.3. Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR)

Functioning as another xenosensor dictating the inductive expression of many drug-metabolizing enzymes, AhR is actually classified into the basic helix-loop-helix protein of the PER-ARNT-SIM (PAS) family not to the nuclear receptor superfamily 143. Nevertheless, AhR shares a number of comparable characteristics with CAR and PXR, which are important in modulating the toxicity and biological functions of many environmental aromatic hydrocarbons and clinically used drugs 144; 145; 146. Upon activation, ligand-bound AhR dissociates with its cytoplasmic chaperon partners and translocates to the nucleus. There, it forms a heterodimer with the aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator and stimulates the expression of its target genes 146; 147. Along with the ever growing list of AhR activators, transactivation of AhR is associated with altered expression of many genes including but not limited to CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1, UGT1As, GST, ADH, ALDH3A1, and BCRP 148; 149,75; 150.

Although AhR-modulated CYP and UGT1A enzymes, and efflux transporter BCRP only have moderate effects on the bioactivation and clearance of CPA and IFO, other AhR target genes such as ADH and ALDH3A1, are proved enzymes that play critical roles in the detoxification of these two oxazaphosphorines (Figure 1). To date, a number of studies have shown that the therapeutic outcomes of CPA- and IFO-based chemotherapy are inversely related to the intracellular levels of ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1.The proactive metabolites of CPA and IFO were oxidized by these enzymes to form the nontoxic 4-keto- and carboxyl-byproducts in competition with generation of the therapeutically active alkylating mustards by β-elimination 75; 151; 152. Indeed, cancer cells with higher expression of ALDH, such as the breast cancer stem-like cells, demonstrate increased resistance to chemotherapy 153. In addition to chemical-stimulated induction, these ALDH enzymes demonstrate tissue specific distribution and developmental changes, and are also over-expressed in certain types of cancer cells 154; 155. Thereby, manipulating tissue-specific expression of ALDH may alter the cellular sensitivity to oxazaphosphorines. Notably, recent studies revealed that other than the prevailing mechanisms of AhR activation stimulated by exogenous ligands, elevation of intracellular second messenger cAMP could also lead to the nuclear translocation of AhR156. Nevertheless, cAMP-mediated translocation of AhR acts as a repressor in lieu of an activator of AhR, which leads to repression of AhR target genes including ALDH 156; 157. As such, drugs and endogenous signaling molecules differentially modulating the function of AhR may affect the expression of ALDH enzymes one way or the other and eventually influence the clinical responses to CPA- and IFO-containing regimens.

4. Concluding Remarks

The oxazaphosphorines CPA and IFO represent the most widely used chemotherapeutic alkylating agents with a history of clinical application for more than 50 years. To date, extensive studies have elucidated the general pharmacology, metabolism, pharmacokinetics and cytotoxicity of these oxazaphosphorines. However, because of the increased polypharmacy in general and in oxazaphosphorine-based chemotherapy in particular, drug-drug interactions associated with CPA and IFO multidrug regimens have become rising concerns in clinical practice. Accumulating evidence thus far established clearly that hepatic CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 differentially contribute to the 4-hydroxylation and N-dechloroethylation of CPA and IFO and many clinical used drugs and environmental compounds can stimulate the inductive expression of these two CYP enzymes. Notably, it is only in the past ten years that marked progress has been achieved in our understanding of the transcriptional regulation of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4, which are controlled by a group of transcription factors, particularly, the CAR and PXR. Importantly, although activation of PXR induces both CYP3A4 and CYP2B6, selective activation of CAR leads to preferential induction of CYP2B6 over CYP3A4 in the liver 142. This notion might be clinically attractive in directed modulation of CPA-based chemotherapy, given the fact that CPA is predominantly bioactivated by CYP2B6 while deactivated through CYP3A4.

Selective cytotoxicity towards tumor but not normal cells is the ultimate goal for all chemotherapeutic agents to achieve. Realizing the specific role of CYP2B6 in the bioactivation of CPA, Waxman and colleagues have reported that locally delivery of adenovirus- or retrovirus-encoding CYP2B expression cassette into tumor cells resulted in increased intracellular CPA 4-hydroxylation and cytotoxicity 158; 159; 160. Thereafter, a number of studies have demonstrated that such strategy could be successful in cell cultures in vitro, tumor xenografts in animal, and to a certain extent in initial clinical trials 158; 160; 161; 162. The current reality, however, is that clinically used CPA and IFO rely predominantly on hepatic CYP-mediated biotransformation and the activated metabolites are transported by erythrocytes to tumors and normal tissues via blood circulation. Moreover, unlike localized solid tumors, systemic chemotherapy is necessary for hematopoietic malignancies such as lymphoma and leukemia, in which CPA continues to be used among the first-line R-COUP regimen. Therefore, understanding the role of xenobiotic receptors in the regulation of key drug-metabolizing enzymes in the liver involving the bioactivation and deactivation of oxazaphosphorine agents is of both scientific significance and clinical importance.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Health Grant (R01, DK061652) and a Seed Grant from University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center.

Abbreviations

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- AKR

aldo-keto reductase

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- BCRP

breast cancer resistance protein

- CAA

chloroacetaldehyde

- CAR

constitutive androstane receptor

- CPA

cyclophosphamide

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- CMF

cyclophosphamide-methotrexate-fluorouracil

- CITCO

6-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazo-[2,1-b][1,3]thiazole-5-carbaldehyde-O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)oxime

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- IFO

ifosfamide

- 4-OH-CPA

4-hydroxycyclophosphamide

- 4-OH-IFO

4-hydroxyifosfamide

- MRP

multidrug resistance-associated protein

- MDR1

multidrug resistance 1

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- RXR

retinoic X receptor

- R-CHOP

rituximab-cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-vincristine-prednisone

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- UGT

UDP-glucuronosyltransferases

References

- 1.Gilman A. The initial clinical trial of nitrogen mustard. Am J Surg. 1963;105:574–578. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(63)90232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MH, Creaven PJ, Tejada F, Hansen HH, Muggia F, Mittelman A, Selawry OS. Phase I clinical trial of isophosphamide (NSC-109724) Cancer Chemother Rep. 1975;59:751–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colvin OM. An overview of cyclophosphamide development and clinical applications. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clavel B, Mathe G, Hayat M. [Phase II therapeutic trial (screening) of ifosfamide in hematosarcomas and solid tumors] Sem Hop Ther. 1975;51:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brock N. Ideas and reality in the development of cancer chemotherapeutic agents, with particular reference to oxazaphosphorine cytostatics. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1986;111:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00402768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sladek NE. Therapeutic efficacy of cyclophosphamide as a function of inhibition of its metabolism. Cancer Res. 1972;32:1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke L, Waxman DJ. Oxidative metabolism of cyclophosphamide: identification of the hepatic monooxygenase catalysts of drug activation. Cancer Res. 1989;49:2344–2350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber GF, Waxman DJ. Activation of the anti-cancer drug ifosphamide by rat liver microsomal P450 enzymes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;45:1685–1694. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90310-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colvin M, Brundrett RB, Kan MN, Jardine I, Fenselau C. Alkylating properties of phosphoramide mustard. Cancer Res. 1976;36:1121–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sladek NE. Metabolism of oxazaphosphorines. Pharmacol Ther. 1988;37:301–355. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(88)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock N. Oxazaphosphorine cytostatics: past-present-future. Seventh Cain Memorial Award lecture. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon J, Alexander MJ, Steinfeld JL. Cyclophosphamide. A clinical study. JAMA. 1963;183:165–170. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03700030041009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colvin M. The comparative pharmacology of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide. Semin Oncol. 1982;9:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Moliterni A, Zambetti M, Brambilla C. Adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil in node-positive breast cancer: the results of 20 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:901–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504063321401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonadonna G, Zambetti M, Moliterni A, Gianni L, Valagussa P. Clinical relevance of different sequencing of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and Fluorouracil in operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1614–1620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coiffier B. Treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Curr Hematol Rep. 2005;4:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mounier N, Briere J, Gisselbrecht C, Emile JF, Lederlin P, Sebban C, Berger F, Bosly A, Morel P, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Reyes F, Gaulard P, Coiffier B. Rituximab plus CHOP (R-CHOP) overcomes bcl-2--associated resistance to chemotherapy in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) Blood. 2003;101:4279–4284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fermand JP, Ravaud P, Chevret S, Divine M, Leblond V, Belanger C, Macro M, Pertuiset E, Dreyfus F, Mariette X, Boccacio C, Brouet JC. High-dose therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: up-front or rescue treatment? Results of a multicenter sequential randomized clinical trial. Blood. 1998;92:3131–3136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demirer T, Buckner CD, Appelbaum FR, Clift R, Storb R, Myerson D, Lilleby K, Rowley S, Bensinger WI. High-dose busulfan and cyclophosphamide followed by autologous transplantation in patients with advanced breast cancer. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:769–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoefer H, Scheef W, Titscher R, Kokron O. [Treatment of bronchogenic cancer and lung metastases of solid tumors with ifosfamid (author's transl)] Osterr Z Onkol. 1974:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brock N. The history of the oxazaphosphorine cytostatics. Cancer. 1996;78:542–547. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960801)78:3<542::AID-CNCR23>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen LM, Creaven PJ. Pharmacokinetics of ifosfamide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1975;17:492–498. doi: 10.1002/cpt1975174492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boddy AV, Yule SM. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of oxazaphosphorines. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;38:291–304. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200038040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bramwell VH, Mouridsen HT, Santoro A, Blackledge G, Somers R, Verweij J, Dombernowsky P, Onsrud M, Thomas D, Sylvester R, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus ifosfamide: a randomized phase II trial in adult soft-tissue sarcomas. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [EORTC], Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1993;31(Suppl 2):S180–S184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bramwell VH, Mouridsen HT, Santoro A, Blackledge G, Somers R, Thomas D, Sylvester R, Van Oosterom A. Cyclophosphamide versus ifosfamide: preliminary report of a randomized phase II trial in adult soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1986;18(Suppl 2):S13–S16. doi: 10.1007/BF00647440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinker A, Kisro J, Letsch C, Bruggemann SK, Wagner T. New insights into the clinical pharmacokinetics of trofosfamide. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40:376–381. doi: 10.5414/cpp40376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.May-Manke A, Kroemer H, Hempel G, Bohnenstengel F, Hohenlochter B, Blaschke G, Boos J. Investigation of the major human hepatic cytochrome P450 involved in 4-hydroxylation and N-dechloroethylation of trofosfamide. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;44:327–334. doi: 10.1007/s002800050985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siebert D. Comparison of the genetic activity of cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide and trofosfamide in host-mediated assays with the gene conversion system of yeast. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1974;81:261–267. doi: 10.1007/BF00305028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strumberg D, Harstrick A, Klaassen U, Muller C, Eberhardt W, Korn MW, Wilke H, Seeber S. Phase II trial of continuous oral trofosfamide in patients with advanced colorectal cancer refractory to 5-fluorouracil. Anticancer Drugs. 1997;8:293–295. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kollmannsberger C, Brugger W, Hartmann JT, Maurer F, Bohm P, Kanz L, Bokemeyer C. Phase II study of oral trofosfamide as palliative therapy in pretreated patients with metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma. Anticancer Drugs. 1999;10:453–456. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunsilius E, Gierlich T, Mross K, Gastl G, Unger C. Palliative chemotherapy in pretreated patients with advanced cancer: oral trofosfamide is effective in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:808–811. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100107742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Douay L, Gorin NC, Laporte JP, Lopez M, Najman A, Duhamel G. ASTA Z 7557 (INN mafosfamide) for the in vitro treatment of human leukemic bone marrows. Invest New Drugs. 1984;2:187–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00232350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pohl J, Bertram B, Hilgard P, Nowrousian MR, Stuben J, Wiessler M. D-19575--a sugar-linked isophosphoramide mustard derivative exploiting transmembrane glucose transport. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;35:364–370. doi: 10.1007/s002800050248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Tian Q, Yung Chan S, Chuen Li S, Zhou S, Duan W, Zhu YZ. Metabolism and transport of oxazaphosphorines and the clinical implications. Drug Metab Rev. 2005;37:611–703. doi: 10.1080/03602530500364023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niculescu-Duvaz I. Glufosfamide (Baxter Oncology) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:1527–1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazur L, Opydo-Chanek M, Stojak M. Glufosfamide as a new oxazaphosphorine anticancer agent. Anticancer Drugs. 22:488–493. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328345e1e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blaney SM, Balis FM, Berg S, Arndt CA, Heideman R, Geyer JR, Packer R, Adamson PC, Jaeckle K, Klenke R, Aikin A, Murphy R, McCully C, Poplack DG. Intrathecal mafosfamide: a preclinical pharmacology and phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1555–1563. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blaney SM, Boyett J, Friedman H, Gajjar A, Geyer R, Horowtiz M, Hunt D, Kieran M, Kun L, Packer R, Phillips P, Pollack IF, Prados M, Heideman R. Phase I clinical trial of mafosfamide in infants and children aged 3 years or younger with newly diagnosed embryonal tumors: a pediatric brain tumor consortium study (PBTC-001) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:525–531. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Tian Q, Chan SY, Duan W, Zhou S. Insights into oxazaphosphorine resistance and possible approaches to its circumvention. Drug Resist Updat. 2005;8:271–297. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seker H, Bertram B, Burkle A, Kaina B, Pohl J, Koepsell H, Wiesser M. Mechanistic aspects of the cytotoxic activity of glufosfamide, a new tumour therapeutic agent. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:629–634. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briasoulis E, Judson I, Pavlidis N, Beale P, Wanders J, Groot Y, Veerman G, Schuessler M, Niebch G, Siamopoulos K, Tzamakou E, Rammou D, Wolf L, Walker R, Hanauske A. Phase I trial of 6-hour infusion of glufosfamide, a new alkylating agent with potentially enhanced selectivity for tumors that overexpress transmembrane glucose transporters: a study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Early Clinical Studies Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3535–3544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.20.3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Briasoulis E, Pavlidis N, Terret C, Bauer J, Fiedler W, Schoffski P, Raoul JL, Hess D, Selvais R, Lacombe D, Bachmann P, Fumoleau P. Glufosfamide administered using a 1-hour infusion given as first-line treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer. A phase II trial of the EORTC-new drug development group. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2334–2340. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00629-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van den Bent MJ, Grisold W, Frappaz D, Stupp R, Desir JP, Lesimple T, Dittrich C, de Jonge MJ, Brandes A, Frenay M, Carpentier AF, Chollet P, Oliveira J, Baron B, Lacombe D, Schuessler M, Fumoleau P. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) open label phase II study on glufosfamide administered as a 60-minute infusion every 3 weeks in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1732–1734. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie W, Barwick JL, Simon CM, Pierce AM, Safe S, Blumberg B, Guzelian PS, Evans RM. Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3014–3023. doi: 10.1101/gad.846800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H, LeCluyse EL. Role of orphan nuclear receptors in the regulation of drug-metabolising enzymes. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:1331–1357. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tompkins LM, Wallace AD. Mechanisms of cytochrome P450 induction. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2007;21:176–181. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brock N, Hilgard P, Peukert M, Pohl J, Sindermann H. Basis and new developments in the field of oxazaphosphorines. Cancer Invest. 1988;6:513–532. doi: 10.3109/07357908809082119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen CS, Lin JT, Goss KA, He YA, Halpert JR, Waxman DJ. Activation of the anticancer prodrugs cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide: identification of cytochrome P450 2B enzymes and site-specific mutants with improved enzyme kinetics. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1278–1285. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang Z, Roy P, Waxman DJ. Role of human liver microsomal CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 in catalyzing N-dechloroethylation of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:961–972. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy P, Yu LJ, Crespi CL, Waxman DJ. Development of a substrate-activity based approach to identify the major human liver P-450 catalysts of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide activation based on cDNA-expressed activities and liver microsomal P-450 profiles. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:655–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dumez H, Reinhart WH, Guetens G, de Bruijn EA. Human red blood cells: rheological aspects, uptake, and release of cytotoxic drugs. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2004;41:159–188. doi: 10.1080/10408360490452031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Highley MS, Schrijvers D, Van Oosterom AT, Harper PG, Momerency G, Van Cauwenberghe K, Maes RA, De Bruijn EA, Edelstein MB. Activated oxazaphosphorines are transported predominantly by erythrocytes. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:1139–1144. doi: 10.1023/a:1008261203803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ren S, Yang JS, Kalhorn TF, Slattery JT. Oxidation of cyclophosphamide to 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide and deschloroethylcyclophosphamide in human liver microsomes. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4229–4235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Highley MS, Harper PG, Slee PH, DeBruijn E. Preferential location of circulating activated cyclophosphamide within the erythrocyte. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:711–712. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(19960301)65:5<711::aid-ijc2910650503>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fenselau C, Kan MN, Rao SS, Myles A, Friedman OM, Colvin M. Identification of aldophosphamide as a metabolite of cyclophosphamide in vitro and in vivo in humans. Cancer Res. 1977;37:2538–2543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang TK, Weber GF, Crespi CL, Waxman DJ. Differential activation of cyclophosphamide and ifosphamide by cytochromes P-450 2B and 3A in human liver microsomes. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5629–5637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ekhart C, Gebretensae A, Rosing H, Rodenhuis S, Beijnen JH, Huitema AD. Simultaneous quantification of cyclophosphamide and its active metabolite 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;854:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaijser GP, Beijnen JH, Jeunink EL, Bult A, Keizer HJ, de Kraker J, Underberg WJ. Determination of chloroacetaldehyde, a metabolite of oxazaphosphorine cytostatic drugs, in plasma. J Chromatogr. 1993;614:253–259. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80316-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Jonge ME, Huitema AD, van Dam SM, Rodenhuis S, Beijnen JH. Effects of co-medicated drugs on cyclophosphamide bioactivation in human liver microsomes. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16:331–336. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200503000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu L, Waxman DJ. Role of cytochrome P450 in oxazaphosphorine metabolism. Deactivation via N-dechloroethylation and activation via 4-hydroxylation catalyzed by distinct subsets of rat liver cytochromes P450. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996;24:1254–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boddy AV, Proctor M, Simmonds D, Lind MJ, Idle JR. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism and clinical effect of ifosfamide in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)00300-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walker D, Flinois JP, Monkman SC, Beloc C, Boddy AV, Cholerton S, Daly AK, Lind MJ, Pearson AD, Beaune PH, et al. Identification of the major human hepatic cytochrome P450 involved in activation and N-dechloroethylation of ifosfamide. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90387-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCune JS, Risler LJ, Phillips BR, Thummel KE, Blough D, Shen DD. Contribution of CYP3A5 to hepatic and renal ifosfamide N-dechloroethylation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1074–1081. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.002279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borner K, Kisro J, Bruggemann SK, Hagenah W, Peters SO, Wagner T. Metabolism of ifosfamide to chloroacetaldehyde contributes to antitumor activity in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:573–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bruggemann SK, Kisro J, Wagner T. Ifosfamide cytotoxicity on human tumor and renal cells: role of chloroacetaldehyde in comparison to 4-hydroxyifosfamide. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2676–2680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boddy AV, English M, Pearson AD, Idle JR, Skinner R. Ifosfamide nephrotoxicity: limited influence of metabolism and mode of administration during repeated therapy in paediatrics. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1179–1184. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fleming RA. An overview of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide pharmacology. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:146S–154S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hong PS, Chan KK. Enzymatic detoxification of phosphoramide mustard by soluble fractions from rat organ tissues. Drug Metab Dispos. 1991;19:568–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giorgianni F, Bridson PK, Sorrentino BP, Pohl J, Blakley RL. Inactivation of aldophosphamide by human aldehyde dehydrogenase isozyme 3. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:325–338. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Townsend AJ, Leone-Kabler S, Haynes RL, Wu Y, Szweda L, Bunting KD. Selective protection by stably transfected human ALDH3A1 (but not human ALDH1A1) against toxicity of aliphatic aldehydes in V79 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2001;130–132:261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kasel D, Jetter A, Harlfinger S, Gebhardt W, Fuhr U. Quantification of cyclophosphamide and its metabolites in urine using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:1472–1478. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yule SM, Boddy AV, Cole M, Price L, Wyllie R, Tasso MJ, Pearson AD, Idle JR. Cyclophosphamide metabolism in children. Cancer Res. 1995;55:803–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dockham PA, Sreerama L, Sladek NE. Relative contribution of human erythrocyte aldehyde dehydrogenase to the systemic detoxification of the oxazaphosphorines. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:1436–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.von Eitzen U, Meier-Tackmann D, Agarwal DP, Goedde HW. Detoxification of cyclophosphamide by human aldehyde dehydrogenase isozymes. Cancer Lett. 1994;76:45–49. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sladek NE. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-mediated cellular relative insensitivity to the oxazaphosphorines. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:607–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jarman M. Formation of 4-ketocyclophosphamide by the oxidation of cyclophosphamide with KMnO4. Experientia. 1973;29:812–814. doi: 10.1007/BF01946302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dirven HA, van Ommen B, van Bladeren PJ. Involvement of human glutathione S-transferase isoenzymes in the conjugation of cyclophosphamide metabolites with glutathione. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6215–6220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dirven HA, Venekamp JC, van Ommen B, van Bladeren PJ. The interaction of glutathione with 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide and phosphoramide mustard, studied by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem Biol Interact. 1994;93:185–196. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Highley MS, Momerency G, Van Cauwenberghe K, Van Oosterom AT, de Bruijn EA, Maes RA, Blake P, Mansi J, Harper PG. Formation of chloroethylamine and 1,3-oxazolidine-2-one following ifosfamide administration in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hill DL, Laster WR, Jr, Kirk MC, el-Dareer S, Struck RF. Metabolism of iphosphamide (2-(2-chloroethylamino)-3-(2-chloroethyl)tetrahydro-2H-1,3,2-oxazaphosphor ine 2-oxide) and production of a toxic iphosphamide metabolite. Cancer Res. 1973;33:1016–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Struck RF, Alberts DS, Horne K, Phillips JG, Peng YM, Roe DJ. Plasma pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide and its cytotoxic metabolites after intravenous versus oral administration in a randomized, crossover trial. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2723–2726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Juma FD, Rogers HJ, Trounce JR. Pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide and alkylating activity in man after intravenous and oral administration. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;8:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lind MJ, Margison JM, Cerny T, Thatcher N, Wilkinson PM. Comparative pharmacokinetics and alkylating activity of fractionated intravenous and oral ifosfamide in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1989;49:753–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bacolod MD, Lin SM, Johnson SP, Bullock NS, Colvin M, Bigner DD, Friedman HS. The gene expression profiles of medulloblastoma cell lines resistant to preactivated cyclophosphamide. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:172–179. doi: 10.2174/156800908784293631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang J, Ng KY, Ho PC. Interaction of oxazaphosphorines with multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4) Aaps J. 2010;12:300–308. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tian Q, Zhang J, Tan TM, Chan E, Duan W, Chan SY, Boelsterli UA, Ho PC, Yang H, Bian JS, Huang M, Zhu YZ, Xiong W, Li X, Zhou S. Human multidrug resistance associated protein 4 confers resistance to camptothecins. Pharm Res. 2005;22:1837–1853. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-7595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lai L, Tan TM. Role of glutathione in the multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4)-mediated efflux of cAMP and resistance to purine analogues. Biochem J. 2002;361:497–503. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Copsel S, Garcia C, Diez F, Vermeulem M, Baldi A, Bianciotti LG, Russel FG, Shayo C, Davio C. Multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4) regulates cAMP cellular levels and controls human leukemia cell proliferation and differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:6979–6988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.166868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Qiu R, Kalhorn TF, Slattery JT. ABCC2-mediated biliary transport of 4-glutathionylcyclophosphamide and its contribution to elimination of 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide in rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:1204–1212. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burger H, Foekens JA, Look MP, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Klijn JG, Wiemer EA, Stoter G, Nooter K. RNA expression of breast cancer resistance protein, lung resistance-related protein, multidrug resistance-associated proteins 1 and 2, and multidrug resistance gene 1 in breast cancer: correlation with chemotherapeutic response. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:827–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nooter K, de la Riviere GB, Klijn J, Stoter G, Foekens J. Multidrug resistance protein in recurrent breast cancer. Lancet. 1997;349:1885–1886. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)63876-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Filipits M, Pohl G, Rudas M, Dietze O, Lax S, Grill R, Pirker R, Zielinski CC, Hausmaninger H, Kubista E, Samonigg H, Jakesz R. Clinical role of multidrug resistance protein 1 expression in chemotherapy resistance in early-stage breast cancer: the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1161–1168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yuan J, Lv H, Peng B, Wang C, Yu Y, He Z. Role of BCRP as a biomarker for predicting resistance to 5-fluorouracil in breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:1103–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0838-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Volk EL, Schneider E. Wild-type breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) is a methotrexate polyglutamate transporter. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5538–5543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, Benet LZ, Brouwer KL, Chu X, Dahlin A, Evers R, Fischer V, Hillgren KM, Hoffmaster KA, Ishikawa T, Keppler D, Kim RB, Lee CA, Niemi M, Polli JW, Sugiyama Y, Swaan PW, Ware JA, Wright SH, Yee SW, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Zhang L. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:215–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Joqueviel C, Martino R, Gilard V, Malet-Martino M, Canal P, Niemeyer U. Urinary excretion of cyclophosphamide in humans, determined by phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26:418–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moore LB, Maglich JM, McKee DD, Wisely B, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Lambert MH, Moore JT. Pregnane X receptor (PXR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and benzoate X receptor (BXR) define three pharmacologically distinct classes of nuclear receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:977–986. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gong H, Sinz MW, Feng Y, Chen T, Venkataramanan R, Xie W. Animal models of xenobiotic receptors in drug metabolism and diseases. Methods Enzymol. 2005;400:598–618. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tolson AH, Wang H. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes by xenobiotic receptors: PXR and CAR. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 62:1238–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Honkakoski P, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. Drug-activated nuclear receptors CAR and PXR. Ann Med. 2003;35:172–182. doi: 10.1080/07853890310008224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tzameli I, Moore DD. Role reversal: new insights from new ligands for the xenobiotic receptor CAR. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nagy L, Schwabe JW. Mechanism of the nuclear receptor molecular switch. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kliewer SA, Goodwin B, Willson TM. The nuclear pregnane X receptor: a key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:687–702. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carnahan VE, Redinbo MR. Structure and function of the human nuclear xenobiotic receptor PXR. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:357–367. doi: 10.2174/1389200054633844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Poso A, Honkakoski P. Ligand recognition by drug-activated nuclear receptors PXR and CAR: structural, site-directed mutagenesis and molecular modeling studies. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2006;6:937–947. doi: 10.2174/138955706777935008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jacobs MN, Dickins M, Lewis DF. Homology modelling of the nuclear receptors: human oestrogen receptorbeta (hERbeta), the human pregnane-X-receptor (PXR), the Ah receptor (AhR) and the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) ligand binding domains from the human oestrogen receptor alpha (hERalpha) crystal structure, and the human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) ligand binding domain from the human PPARgamma crystal structure. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;84:117–132. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Watkins RE, Wisely GB, Moore LB, Collins JL, Lambert MH, Williams SP, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Redinbo MR. The human nuclear xenobiotic receptor PXR: structural determinants of directed promiscuity. Science. 2001;292:2329–2333. doi: 10.1126/science.1060762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Klaassen CD, Slitt AL. Regulation of hepatic transporters by xenobiotic receptors. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:309–328. doi: 10.2174/1389200054633826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang H, Tompkins LM. CYP2B6: new insights into a historically overlooked cytochrome P450 isozyme. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:598–610. doi: 10.2174/138920008785821710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang H, Negishi M. Transcriptional regulation of cytochrome p450 2B genes by nuclear receptors. Curr Drug Metab. 2003;4:515–525. doi: 10.2174/1389200033489262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schuler U, Ehninger G, Wagner T. Repeated high-dose cyclophosphamide administration in bone marrow transplantation: exposure to activated metabolites. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1987;20:248–252. doi: 10.1007/BF00570495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hartley JM, Hansen L, Harland SJ, Nicholson PW, Pasini F, Souhami RL. Metabolism of ifosfamide during a 3 day infusion. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:931–936. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lindley C, Hamilton G, McCune JS, Faucette S, Shord SS, Hawke RL, Wang H, Gilbert D, Jolley S, Yan B, LeCluyse EL. The effect of cyclophosphamide with and without dexamethasone on cytochrome P450 3A4 and 2B6 in human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:814–822. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.7.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hariparsad N, Chu X, Yabut J, Labhart P, Hartley DP, Dai X, Evers R. Identification of pregnane-X receptor target genes and coactivator and corepressor binding to promoter elements in human hepatocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1160–1173. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ma X, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ. The pregnane X receptor: from bench to bedside. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4:895–908. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.7.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Harmsen S, Meijerman I, Febus CL, Maas-Bakker RF, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. PXR-mediated induction of P-glycoprotein by anticancer drugs in a human colon adenocarcinoma-derived cell line. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:765–771. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1221-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Harmsen S, Meijerman I, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. Nuclear receptor mediated induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 by anticancer drugs: a key role for the pregnane X receptor. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0842-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hustert E, Zibat A, Presecan-Siedel E, Eiselt R, Mueller R, Fuss C, Brehm I, Brinkmann U, Eichelbaum M, Wojnowski L, Burk O. Natural protein variants of pregnane X receptor with altered transactivation activity toward CYP3A4. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1454–1459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lim YP, Huang JD. Pregnane X receptor polymorphism affects CYP3A4 induction via a ligand-dependent interaction with steroid receptor coactivator-1. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:369–382. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32803e40d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang D, Li L, Fuhrman J, Ferguson S, Wang H. The role of constitutive androstane receptor in oxazaphosphorine-mediated induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes in human hepatocytes. Pharm Res. 2011;28:2034–2044. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0429-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tolson AH, Li H, Eddington ND, Wang H. Methadone induces the expression of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes through the activation of pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1887–1894. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Burk O, Arnold KA, Nussler AK, Schaeffeler E, Efimova E, Avery BA, Avery MA, Fromm MF, Eichelbaum M. Antimalarial artemisinin drugs induce cytochrome P450 and MDR1 expression by activation of xenosensors pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1954–1965. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. Phenobarbital response elements of cytochrome P450 genes and nuclear receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:123–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Simonsson US, Lindell M, Raffalli-Mathieu F, Lannerbro A, Honkakoski P, Lang MA. In vivo and mechanistic evidence of nuclear receptor CAR induction by artemisinin. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:647–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Qatanani M, Moore DD. CAR, the continuously advancing receptor, in drug metabolism and disease. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:329–339. doi: 10.2174/1389200054633899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kawamoto T, Sueyoshi T, Zelko I, Moore R, Washburn K, Negishi M. Phenobarbital-responsive nuclear translocation of the receptor CAR in induction of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6318–6322. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Maglich JM, Parks DJ, Moore LB, Collins JL, Goodwin B, Billin AN, Stoltz CA, Kliewer SA, Lambert MH, Willson TM, Moore JT. Identification of a novel human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) agonist and its use in the identification of CAR target genes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17277–17283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Li H, Chen T, Cottrell J, Wang H. Nuclear translocation of adenoviral-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein-tagged-human constitutive androstane receptor (hCAR): a novel tool for screening hCAR activators in human primary hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1098–1106. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.026005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lamba J, Lamba V, Schuetz E. Genetic variants of PXR (NR1I2) and CAR (NR1I3) and their implications in drug metabolism and pharmacogenetics. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:369–383. doi: 10.2174/1389200054633880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lamba JK. Pharmacogenetics of the constitutive androstane receptor. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:71–83. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ikeda S, Kurose K, Jinno H, Sai K, Ozawa S, Hasegawa R, Komamura K, Kotake T, Morishita H, Kamakura S, Kitakaze M, Tomoike H, Tamura T, Yamamoto N, Kunitoh H, Yamada Y, Ohe Y, Shimada Y, Shirao K, Kubota K, Minami H, Ohtsu A, Yoshida T, Saijo N, Saito Y, Sawada J. Functional analysis of four naturally occurring variants of human constitutive androstane receptor. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ikeda S, Kurose K, Ozawa S, Sai K, Hasegawa R, Komamura K, Ueno K, Kamakura S, Kitakaze M, Tomoike H, Nakajima T, Matsumoto K, Saito H, Goto Y, Kimura H, Katoh M, Sugai K, Minami N, Shirao K, Tamura T, Yamamoto N, Minami H, Ohtsu A, Yoshida T, Saijo N, Saito Y, Sawada J. Twenty-six novel single nucleotide polymorphisms and their frequencies of the NR1I3 (CAR) gene in a Japanese population. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2003;18:413–418. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.18.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Auerbach SS, Ramsden R, Stoner MA, Verlinde C, Hassett C, Omiecinski CJ. Alternatively spliced isoforms of the human constitutive androstane receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3194–3207. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Jinno H, Tanaka-Kagawa T, Hanioka N, Ishida S, Saeki M, Soyama A, Itoda M, Nishimura T, Saito Y, Ozawa S, Ando M, Sawada J. Identification of novel alternative splice variants of human constitutive androstane receptor and characterization of their expression in the liver. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:496–502. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gray MA, Peacock JN, Squires EJ. Characterization of the porcine constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) and its splice variants. Xenobiotica. 2009;39:915–930. doi: 10.3109/00498250903330348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Auerbach SS, Stoner MA, Su S, Omiecinski CJ. Retinoid X receptor-alpha-dependent transactivation by a naturally occurring structural variant of human constitutive androstane receptor (NR1I3) Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1239–1253. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Auerbach SS, Dekeyser JG, Stoner MA, Omiecinski CJ. CAR2 displays unique ligand binding and RXRalpha heterodimerization characteristics. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:428–439. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.012641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.DeKeyser JG, Laurenzana EM, Peterson EC, Chen T, Omiecinski CJ. Selective phthalate activation of naturally occurring human constitutive androstane receptor splice variants and the pregnane X receptor. Toxicol Sci. 2011;120:381–391. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chen T, Tompkins LM, Li L, Li H, Kim G, Zheng Y, Wang H. A single amino acid controls the functional switch of human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) 1 to the xenobiotic-sensitive splicing variant CAR3. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:106–115. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Faucette SR, Zhang TC, Moore R, Sueyoshi T, Omiecinski CJ, LeCluyse EL, Negishi M, Wang H. Relative activation of human pregnane X receptor versus constitutive androstane receptor defines distinct classes of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 inducers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:72–80. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.112136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.DeKeyser JG, Stagliano MC, Auerbach SS, Prabhu KS, Jones AD, Omiecinski CJ. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate is a highly potent agonist for the human constitutive androstane receptor splice variant CAR2. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:1005–1013. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.053702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Faucette SR, Sueyoshi T, Smith CM, Negishi M, Lecluyse EL, Wang H. Differential regulation of hepatic CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 genes by constitutive androstane receptor but not pregnane X receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1200–1209. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Burbach KM, Poland A, Bradfield CA. Cloning of the Ah-receptor cDNA reveals a distinctive ligand-activated transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8185–8189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Denison MS, Phelan D, Winter GM, Ziccardi MH. Carbaryl, a carbamate insecticide, is a ligand for the hepatic Ah (dioxin) receptor. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;152:406–414. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Phelan D, Winter GM, Rogers WJ, Lam JC, Denison MS. Activation of the Ah receptor signal transduction pathway by bilirubin and biliverdin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;357:155–163. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Quattrochi LC, Tukey RH. Nuclear uptake of the Ah (dioxin) receptor in response to omeprazole: transcriptional activation of the human CYP1A1 gene. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;43:504–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lesca P, Peryt B, Larrieu G, Alvinerie M, Galtier P, Daujat M, Maurel P, Hoogenboom L. Evidence for the ligand-independent activation of the AH receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;209:474–482. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sugatani J, Kojima H, Ueda A, Kakizaki S, Yoshinari K, Gong QH, Owens IS, Negishi M, Sueyoshi T. The phenobarbital response enhancer module in the human bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT1A1 gene and regulation by the nuclear receptor CAR. Hepatology. 2001;33:1232–1238. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Yueh MF, Huang YH, Hiller A, Chen S, Nguyen N, Tukey RH. Involvement of the xenobiotic response element (XRE) in Ah receptor-mediated induction of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15001–15006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Sladek NE. Transient induction of increased aldehyde dehydrogenase 3A1 levels in cultured human breast (adeno)carcinoma cell lines via 5'-upstream xenobiotic, and electrophile, responsive elements is, respectively, estrogen receptor-dependent and -independent. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;143–144:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Sladek NE, Kollander R, Sreerama L, Kiang DT. Cellular levels of aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1) as predictors of therapeutic responses to cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy of breast cancer: a retrospective study. Rational individualization of oxazaphosphorine-based cancer chemotherapeutic regimens. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;49:309–321. doi: 10.1007/s00280-001-0412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Sladek NE. Leukemic cell insensitivity to cyclophosphamide and other oxazaphosphorines mediated by aldehyde dehydrogenase(s) Cancer Treat Res. 2002;112:161–175. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1173-1_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]