Abstract

Discriminatory experiences are not only momentarily distressing, but can also increase risk for lasting physical and psychological problems. Specifically, significantly higher rates of depression and depressive symptoms are reported among people who are frequently the target of prejudice. Given the gravity of this problem, this research focuses on an individual difference, trait mindfulness, as a protective factor in the association between discrimination and depressive symptoms. In a community sample of 605 individuals, trait mindfulness dampens the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Additionally, mindfulness provides benefits above and beyond those of positive emotions. Trait mindfulness may thus operate as a protective individual difference for targets of discrimination.

Keywords: Trait mindfulness, Perceived discrimination, Depressive symptoms, Positive emotions

The experience of discrimination deprives a person of opportunities and can damage mental and physical health (see Pascoe & Richman, 2009, for review). In this paper, we test the hypothesis that trait mindfulness may diminish the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms. Mindfulness is defined as a perspective of non-judgmental attention and awareness of the present moment (Bishop et al., 2004). A growing body of research suggests that mindfulness promotes successful coping in stressful situations, and thus, may serve as a buffer against the stress of experiencing discrimination.

Understanding the relationship between perceived discrimination and depression

The experience of discrimination is often hurtful, humiliating, and even traumatizing. Researchers have found a robust relationship between perceived discrimination and depression (Pascoe & Richman, 2009). Kessler and colleagues (1999) found that perceived discrimination was significantly associated with nonspecific distress and major depression. Noh and colleagues (1999) found that in a sample of Southeast Asian immigrants, those who reported experiencing racial discrimination had higher levels of depression than those who did not experience discrimination. Finally, a longitudinal study found that increasing rates of discriminatory experiences over a 5 year period was associated with increases in depressive symptoms over the same time period (Schulz et al., 2006).

The relationship between discrimination and depression has commonly been understood in terms of a stress and coping framework. Events appraised as threatening, such as experiences of discrimination, result in a stress response, which mobilizes mental and physical resources to fight or avoid the stressor. Although momentary activation of the stress response may be beneficial to combat or escape threatening situations, prolonged stress activation depletes psychological and physiological resources and causes psychological and physical damage. Therefore, individuals who frequently experience discrimination are at risk for prolonged stress and its harmful long term effects (Richman et al., 2010).

The consequences of prolonged stress, however, depend on an individual's coping strategy - his or her cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage the internal and external demands of a stressful event (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Generally, coping has two main roles: (1) dealing with the problem causing distress and (2) regulating emotions triggered by the distressing event (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Previous research has shown mindfulness to be a successful coping strategy for a number of other mental health problems, and it is a consistent predictor of greater well-being more broadly (for review see Brown, Ryan & Creswell, 2007). Thus, we aimed to test whether higher levels of mindfulness could buffer the effects of experiencing discrimination.

The moderating role of mindfulness on the discrimination-depressive symptoms relationship

Mindfulness could dampen the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms through at least three mechanisms. First, mindfulness is associated with improved understanding of personal emotions, which is thought to improve one's ability to regulate emotions and hasten recovery from negative emotions (Coffey, Hartman, & Fredrickson, 2010). Second, mindfulness is thought to improve individuals’ ability to mentally separate experiences from sense of self-worth (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007), a trait which predicts fewer automatic negative thoughts and greater ability to let go of negative thoughts (Frewen et al., 2008). Finally, mindfulness has been linked to lower general emotional reactivity (Arch & Craske, 2006), allowing for more objective observations and more appropriate and deliberate responses to situations (Barnes et al., 2007).

Thus, people higher in mindfulness who experience discrimination may have greater ability to regulate negative emotions, decouple discrimination from sense of self-worth, make objective observations and successfully navigate interpersonal interactions than can those who are less mindful. All of these abilities suggest that greater mindfulness should mitigate the consequences of discriminatory experiences.

The buffering effects of mindfulness versus positive emotions

Previous research has found that positive emotions offset the negative effects of discrimination (Ong and Edwards, 2008). Furthermore, mindfulness and positive emotions tend to be associated; people who have greater positive emotional reactivity are more likely to be mindful (Catalino & Fredrickson, 2011). To test whether the protective effects of mindfulness are distinct from those of positive emotions, we examined whether the effects of mindfulness remained after controlling for individual differences in the experience of positive emotions.

Current Research

Given the ubiquity of discrimination and its negative consequences, the current project sought to investigate whether trait mindfulness moderates the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. First, we hypothesized that mindfulness would moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Second, we hypothesized that this relationship would be independent of the effects of positive emotions.

Methods

Participants

Community-members were recruited to participate in a web-based survey in exchange for $20 compensation.1 The sample was recruited as the screening phase for another experiment on optimal mental health (Catalino & Fredrickson, 2011). The screening phase aimed to collect as many individuals as possible in order to obtain a wide range of people experiencing varying levels of mental health. Participants were recruited through several methods including flyers and electronic advertisements posted on Craig's List, from January to May in 2007. Any U.S. resident was eligible to take part in the survey. A sample of 624 adults participated. Nineteen subjects did not complete all of the measures pertinent to the current research question, so the sample used for our analyses was N=605. A power analysis indicated that our sample size provided high power (1-β)>.9 to detect even a small effect size (r=.20). Table 1 displays the sample's sociodemographic and descriptive information on the variables of interest for the current research.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic information and statistics on variables of interest.

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean | 40.93 | |

| SD | 9.60 | |

| Range | 19-65 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | N = 241 | |

| Female | N = 361 | |

| Missing | N = 3 | |

| Race | ||

| White | N = 469 | |

| Black | N = 85 | |

| South Asian | N = 25 | |

| East Asian | N = 8 | |

| Hispanic | N = 7 | |

| American Indian | N = 2 | |

| Other | N = 2 | |

| Missing | N = 3 | |

| Positive Emotion | ||

| Mean | 3.26 | |

| SD | 0.87 | |

| Range | 1.08-5.00 | |

| Perceived Discrimination | ||

| Mean | 1.64 | |

| SD | 0.64 | |

| Range | 1.00-5.39 | |

| Mindfulness | ||

| Mean | 3.40 | |

| SD | 0.49 | |

| Range | 1.82-4.83 | |

| Depressive Symptoms | ||

| Mean | 1.36 | |

| SD | 0.46 | |

| Range | 1.00-3.71 |

Materials

Perceived discrimination

Participants completed a modified version of the Perceived Racism Scale (McNeilly et al., 1996; Richman et al., 2010). The measure was adapted to assess general discriminatory experiences as opposed to racially specific discriminatory experiences. This adaptation of the Perceived Racism Scale has been used in previous research (Richman et al., 2010). Participants were asked how many times they experienced situations such as “People ‘talk down’ to me”. Responses were made on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (several times a day). The mean of these 33 items served as the participant's measure of perceived discrimination (α=.96). At the end of the scale, participants were asked to indicate the main source for their experiences of unfair treatment (Race or ethnicity; Gender; Sexual Orientation; Age; Religion; Income Level; Physical Appearance; Body Weight).

Mindfulness

We assessed trait mindfulness using the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006). The FFMQ assesses the following aspects of mindfulness: (1) nonreactivity to inner experience, (2) observing present sensations, feelings, and thoughts, (3) acting with awareness, (4) describing or labeling events with words, and (5) being nonjudgmental of experiences. Due to a computer programming error, data for eight out of a total of 39 items were not collected. All participants missed the same eight items: six from the nonreactivity to inner experience factor and two items from the nonjudgmental of experiences factor. The measure was scored by averaging all of the factor means for each individual in order to give equal weight to each factor in assessing mindfulness, as suggested by the developers of the scale (Baer et al., 2006). Despite this error the scale's reliability was high (α=.90).

Positive emotions

Positive emotions were assessed using the Positive Emotions subscale from the modified Differential Emotions Scale (Fredrickson et al., 2003; original DES Izard, 1977). This instrument measures how often participants felt discrete positive emotions (e.g. amusement, awe, love) during the past two weeks (1=not at all; 5=most of the time). This measure was scored by averaging the ratings of the 12 items for each participant (α=.95).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988). This 21-item measure assesses the degree to which individuals self-report symptoms of depression (e.g. “During the past few days...” 1=I did not feel sad.; 2=I felt sad.; 3=I felt sad and I couldn't snap out of it.; 4=I felt so sad or unhappy that I couldn't stand it). The measure was scored by averaging the ratings (α=.95).2

Results

Descriptive findings

We found the sample represented a diverse range of reasons for experiencing prejudice. The most common source of discrimination was gender (19.7%), followed by race or ethnicity (17%), body weight (14.4%) and age (14.3%). Because Pascoe & Richman (2009) found that the deleterious effects of discrimination did not vary by type of discrimination, we decided to collapse across discrimination type. Next, we assessed the correlational relationships among the key variables (Table 2). Replicating previous work, perceived discrimination was positively correlated with depressive symptoms (r=.44, p<.0001), and positive emotions and mindfulness were negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (r= −.51, p<.0001; r= −.44, p<.0001, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Correlations among variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depressive Symptoms | ||||

| 2. Perceived Discrimination | 0.44** | |||

| 3. Mindfulness | −0.44** | −0.30** | ||

| 4. Positive Emotions | −0.51** | −0.12** | 0.54** |

Note.

p<.01

Main and interactive effects

We hypothesized that the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms would be moderated by trait mindfulness. This implies a mindfulness by perceived discrimination interaction. Given that the independent and dependent variables were continuous, we tested this hypothesis using multiple regression. The main effects were entered on the first step followed by interactions on the second step. Perceived discrimination, mindfulness, and depressive symptoms were standardized before being entered into the regression equation. The interaction was computed by multiplying the standardized scores of perceived discrimination and mindfulness. We report and interpret the unstandardized regression coefficients.

Consistent with previous research, individuals who experienced more discrimination were significantly more likely to experience depressive symptoms (b=.28, p< .0001) (see Table 3). Also, individuals who were more mindful experienced significantly fewer depressive symptoms (b= −.37, p<.0001). In support of our hypothesis, we found a significant interaction between perceived discrimination and mindfulness (b= −.12, p=.004), providing initial evidence that mindfulness acts as a protective factor.3,4 As indicated by the significant interaction term, the simple slopes are significantly different from each other.

TABLE 3.

Regression analyses predicting depressive symptoms from the interaction between mindfulness and perceived discrimination and control variables.

| Variable | b | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis 1 | Perceived Discrimination | 0.28 | < 0.001 |

| Mindfulness | −0.37 | < 0.001 | |

| Mindfulness X Perceived Discrimination | −0.12 | 0.004 | |

| Analysis 2 | Positive Emotions | −0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.35 | < 0. 001 | |

| Mindfulness | −0.14 | < 0.001 | |

| Positive Emotions X Perceived Discrimination | −0.14 | < 0.001 | |

| Mindfulness X Perceived Discrimination | −0.08 | 0.038 | |

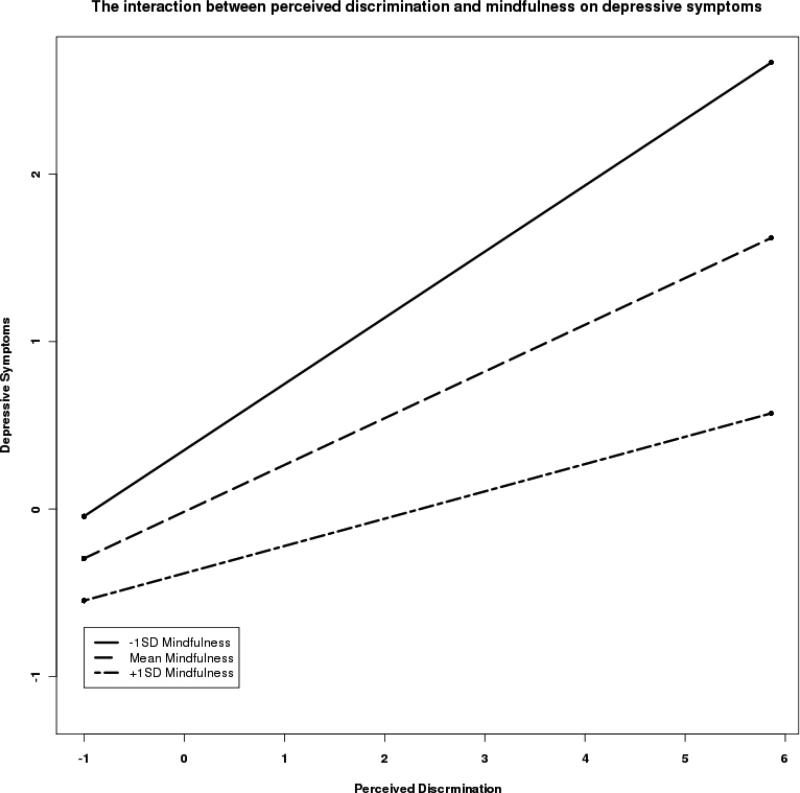

To further probe the interaction, separate regression lines were estimated for individuals high (one standard deviation above the mean), moderate (at the mean), and low (one standard deviation below the mean) on mindfulness (see Figure 1; Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). The simple slope relating perceived discrimination to depressive symptoms at low levels of mindfulness was b=.40 (t=8.83, p<.0001); the simple slope at the mean of mindfulness was b=.28 (t=6.24, p<.0001); and at high levels of mindfulness the slope was b=.16 (t=2.13, p=.04). The relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms was never completely eliminated by mindfulness, but it was significantly reduced at higher levels of mindfulness. The results suggest that more mindful individuals have a weakened relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

The interaction between perceived discrimination and mindfulness on depression. The three lines represent three levels of trait mindfulness, 1 standard deviation below the mean, 1 standard deviation above the mean, and at the mean of trait mindfulness.

To test our hypothesis that these effects would remain after controlling for positive emotions, we added the standardized positive emotion scores in the first step and the interaction between perceived discrimination and positive emotions in the second step. The interaction was computed by multiplying the standardized scores. We report and interpret the unstandardized estimates. This strategy allowed us to test whether the protective quality of mindfulness was distinct from that of positive emotions.

As before, the results revealed a significant main effect of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms (b=.35, p<.0001) (see Table 3). There was again a significant main effect of mindfulness on depressive symptoms such that individuals who were more mindful were less likely to experience depressive symptoms (b= −.14, p<.0001). Additionally, there was a significant main effect of positive emotions on depressive symptoms such that individuals who experienced more positive emotions were less likely to experience depressive symptoms (b= −.40, p<.0001). Replicating previous work, the interaction between positive emotions and perceived discrimination was significant as well (b= −.14, p<.0001), indicating that individuals who experience more positive emotions displayed a lower correlation between discrimination experiences and depressive symptoms (Ong & Edwards, 2008). Central to our hypothesis, the interaction between mindfulness and perceived discrimination remained significant when controlling for both positive emotions and the interaction between positive emotions and perceived discrimination (b= −.08, p=.04). These results suggest that mindfulness acts as a protective mechanism that reduces the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, independent of the protective effects of positive emotions.5

Discussion

In line with our hypothesis, mindfulness appears to buffer the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Given the well-documented association between perceived discrimination and negative mental and physical health outcomes, uncovering psychological mechanisms to mitigate these negative consequences could benefit individuals facing discrimination.

The current research also found that the buffering quality of mindfulness is not entirely subsumed by the moderating effects of positive emotions. Rather, mindfulness confers unique benefits beyond those accounted for by positive emotions, likely because individuals higher in mindfulness more successfully reduce the experience of negative emotions (Coffey, Hartman, & Fredrickson, 2010). Therefore, mindful individuals may be better able to reduce the emotional intensity and duration of the discriminatory experience, allowing for improved coping following an experience of discrimination.

A limitation of this research is that we cannot ascertain the causal direction between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Research has shown that perceived discrimination predicts depression (Brown et al., 2000), but people with more depressive symptoms may also perceive more discrimination, or both depression and perceptions of discrimination might be caused by an unobserved third variable. Our data cannot assess the causal role of mindfulness in protecting individuals against the stress of discrimination. Future research should investigate the causal direction between perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and mindfulness.

The current research lays the ground work to explore mindfulness-based interventions to help reduce the psychological impact of discriminatory experiences. Many types of interventions, from full scale meditation training interventions to lab inductions, have been found to boost state (Arch & Craske, 2006) and build trait mindfulness (Shapiro et al., 2011). Extending the research in this way would determine whether mindfulness could potentially be implemented widely as a strategy for coping with prejudicial experiences.

The current research is not meant to suggest that the burden is on the targets of discrimination to learn how better to cope with these experiences. Ideally, structural and cultural changes would reduce discriminatory practices at the societal level. But, until such changes take place, we hope this research will highlight potential strategies to mitigate the negative toll discriminatory experiences have on individual targets.

Conclusion

The current research suggests that mindfulness may be a useful coping mechanism that can mitigate the psychological toll of discrimination. In addition, mindfulness seems to have an added benefit above and beyond positive emotions. Therefore, mindfulness appears to provide distinct benefits for targets of prejudice.

Highlights.

Does mindfulness mitigates the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms?

The researched employed a large community sample and assessed many sources of discrimination.

We found mindfulness dampens the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms.

Additionally, mindfulness provided benefits above and beyond those of positive emotions.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge colleagues who have provided feedback on this manuscript: Kristjen B. Lundberg and Andrew M. Iannuzzi.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The study was approved by the University of North Carolina's IRB. Participants provided informed consent prior to participant. In addition, the data were completely de-identified.

The depressive symptoms and perceived discrimination variables were slightly positively skewed, so we re-ran the analyses after conducting a square-root transformation on these variables to reduce skew. All significant effects remained significant.

All findings still hold when controlling for gender and race of the participant.

The significant interaction between perceived discrimination and mindfulness is driven by the Observe, Nonjudgmental, and Nonreactive facets of mindfulness.

All findings still hold when controlling for gender and race of the participant.

References

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Mechanisms of mindfulness: Emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1849–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Brown KW, Krusemark E, Campbell WK, Rogge RD. The role of mindfulness in romantic relationship satisfaction and responses to relationship stress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2007;33:482–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, Segal ZV, Abbey S, Speca M, Velting D, Devins G. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology. 2004:230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: Theoretical Foundations and Evidence for its Salutary Effects. Psychological Inquiry. 2007;18:211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Williams DR, Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Sellers SL, Brown KT. Being Black and feeling blue: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race & Society. 2000;2:117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Catalino LI, Fredrickson BL. A Tuesday in the life of a flourisher: The role of positive emotional reactivity in optimal mental health. Emotion. 2011;11:938–950. doi: 10.1037/a0024889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey KA, Hartman M, Fredrickson BL. Deconstructing mindfulness and constructing mental health: Understanding mindfulness and its mechanisms of action. Mindfulness. 2010;1:235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. An analysis of coping in middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1980;21:219–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, Larkin GR. What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotion following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Personality Processes and Individual Difference. 2003;84:365–376. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Evans EM, Maraj N, Dozois DA, Partridge K. Letting go: Mindfulness and negative automatic thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:758–774. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE. Human emotions. Plenum Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of percieved discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeilly MD, Anderson NB, Armstead CA, Clark R, Corbett M, Robinson EL, Pieper CF, Lepisto EM. The perceived racism scale: A multidimensional assessment of the White racism among African Americans. Ethnicity & Disease. 1996:154–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: A study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. Journal of Health And Social Behavior. 1999;40:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Edwards L. Positive affect and adjustment to perceived racism. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27:105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Richman L, Pek J, Pascoe E, Bauer DJ. The effects of perceived discrimination on ambulatory blood pressure and affective responses to interpersonal stress modeled over 24 hours. Health Psychology. 2010;25:403–411. doi: 10.1037/a0019045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A, Gravlee C, Williams D, Israel B, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Brown K, Thoresen C, Plante TG. The moderation of mindfulness-based stress reduction effects by trait mindfulness: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67:267–277. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]