Abstract

Objectives

The present study describes latex sensitisation and allergy prevalence and associated factors among healthcare workers using hypoallergenic latex gloves at King Edward VIII Hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

A tertiary hospital in eThekwini municipality, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Participants

600 healthcare workers were randomly selected and 501 (337 exposed and 164 unexposed) participated. Participants who were pregnant, with less than 1 year of work as a healthcare worker and a history of anaphylactic reaction were excluded from the study.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Latex sensitisation and latex allergy were the outcome of interest and they were successfully measured.

Results

The prevalence of latex sensitisation and allergy was observed among exposed workers (7.1% and 5.9%) and unexposed workers (3.1% and 1.8%). Work-related allergy symptoms were significantly higher in exposed workers (40.9%, p<0.05). Duration of employment was inversely associated with latex allergy (OR 0.9; 95% CI 0.8 to 0.9). The risk of latex sensitisation (OR 4.2; 95% CI 1.2 to 14.1) and allergy (OR 5.1; 95% CI 1.2 to 21.2) increased with the exclusive use of powder-free latex gloves. A dose–response relationship was observed for powdered latex gloves (OR 1.1; 95% CI 1.0 to 1.2). Atopy (OR 1.5; 95% CI 0.7 to 3.3 and OR 1.4; 95% CI 0.6 to 3.2) and fruit allergy (OR 2.3; 95% CI 0.8 to 6.7 and OR 3.1; 95% CI 1.1 to 9.2) also increased the risk of latex sensitisation and allergy.

Conclusions

This study adds to previous findings that healthcare workers exposed to hypoallergenic latex gloves are at risk for developing latex sensitisation highlighting its importance as an occupational hazard in healthcare. More research is needed to identify the most cost effective way of implementing a latex-free environment in resource-limited countries, such as South Africa. In addition more cohort analysis is required to better understand the chronicity of illness and disability associated with latex allergy.

Keywords: Latex, Hypoallergenic, Healthcare workers, South Africa

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The presence of a control group providing a background prevalence of latex sensitisation in this population and a random selection of participants which minimised the potential of participant bias that arises with a volunteer approach.

This study was limited by the cross-sectional study design as it only allowed for the determination of the prevalence of latex sensitisation; recall bias with regard to the number of gloves used in the past seven working days and the self-reporting of personal and family atopic disorders may have resulted in the misclassification of exposure and atopy, respectively.

Introduction

Latex allergy (LA) as an occupational disease among healthcare workers (HCWs) gained recognition after Nutter1 published a case report of contact urticaria in HCW in 1979. The increase in prevalence coincided with the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the introduction of ‘universal precautions’ in the healthcare industry which had resulted in the increased use of latex gloves among HCWs.2

Latex gloves are preferred due to their superior barrier and physical properties as compared with the non-latex gloves.3 International epidemiological studies have reported the prevalence of LA among HCWs to range between 2% and 22% depending on the population and diagnostic methods used.4–11 The prevalence in the general population has been reported to range between 1% and 6%.12 13 In South Africa studies among HCWs reported a latex sensitisation prevalence of between 2.7% and 20.8%.14–16 LA in HCWs is a compensable disease in South Africa in terms of the Compensation of Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act No. 130 of 1993.17

Powdered latex gloves were identified as an important risk factor for latex sensitisation and allergy in HCWs as they were found to contain high allergenic protein content.18 Following these findings, hypoallergenic gloves with low allergen content namely, low-powdered and powder-free latex gloves were introduced. The European definition of powder-free gloves is gloves with powder content not exceeding 2 mg/glove and leachable latex protein which is as low as is reasonably practical.19

Hypoallergenic gloves have been associated with reduced latex aeroallergen concentrations, reduced conversion rates and a subsequent decrease in clinic visits, and compensation claims for latex-induced occupational asthma and allergic contact dermatitis among HCWs.18 20 As much as the use of low or powder-free gloves has been shown to reduce latex-related symptoms, other studies have shown that exposed HCWs still exhibit symptoms at very low levels of measureable airborne latex allergens.21 Most studies have reported on the airborne levels and inhalational route of exposure hence the recommendation on low-powdered or powder-free latex gloves. There is little consideration given to the dermal route of exposure despite the fact that exposure is as a result of direct contact in these instances.22 Eliminating the cornstarch powder only removed the carrier and not the source of allergen which is in the latex itself. Therefore workers using powder-free gloves are still exposed to the allergenic content of latex gloves. It has been shown that different brands from different suppliers contain differing levels of protein due to a lack of standards in latex glove manufacture.23 A South African study reported that some powder-free latex gloves were found to have a high allergenic protein content.23 HCWs using these gloves are exposed via direct dermal contact and are at a risk for developing latex sensitisation which maybe asymptomatic and if exposure continues they can later develop LA which presents with clinical manifestations.

While it is important to diagnose and manage an individual worker with LA in the early stages of the disease, a complete control of hazardous substances in the workplace is equally if not more important. While a latex-free work environment would be a preferred control strategy, a substitution of powdered latex gloves with powder-free gloves was shown to be cost effective and associated with improved clinical outcome.20 24–26 As a result this was adopted as the most reasonable and practical approach in addressing the problem of LA among HCWs both internationally and to some extent nationally.27–29 This has proven to reduce latex-induced clinical outcomes. Even with this intervention, studies in Western countries such as Germany and the UK have shown that the risk of latex sensitisation still exists and more needs to be carried out to protect HCWs.30 31

The current study described the prevalence of latex sensitisation and allergy among HCWs who use hypoallergenic powder free and lightly powdered latex gloves.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a cross-sectional study conducted between July 2011 and January 2012. The study location was King Edward VIII hospital, the second largest hospital in the Southern hemisphere, providing regional and tertiary services to the whole of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. It has a bed status of 1300 and has a workforce of 2400. The hospital was chosen due to the large workforce with different departments, and the policy of using both powder-free and low-powdered latex gloves for approximately 10 years.

The study population was limited to HCWs currently employed at King Edward VIII Hospital for more than 12 months. HCWs were defined as all personnel employed in the hospital.

The prevalence of latex sensitisation in HCWs using powdered latex gloves in the Western Cape Province was 11.9% in 2001.16 We expected the prevalence at King Edward VIII hospital to be less than the 11.9% observed in the Western Cape Province due to the adoption of a hypoallergenic latex glove policy in 2001. Using EPI Info calculator V.3.04.04., it was assumed that 50% of sensitised workers have remained sensitised despite the introduction of hypoallergenic latex gloves 10 years prior. Using an expected latex sensitisation prevalence of 6% for the exposed group and the prevalence among the general population being reported as less than 1%, the required sample size was calculated to be 585 participants two exposed participants for every one non-exposed participant (exposed=390; unexposed=195). HCWs were considered to be exposed if they were likely to use gloves. Unexposed HCWs were drawn from the administrative staff of the hospital.

Questionnaire

We used an adaptation of the questionnaire used in an epidemiological study conducted at Groote Schuur in 200116 with permission from Professor Paul Potter, Allergology Unit, Medical School, University of Cape Town. The questionnaire containing open-ended and closed-ended questions was adapted to include items on exposure assessment. The questionnaire was administered by a trained research assistant immediately prior to the skin prick test (SPT). The questionnaire collected data on the participants’ demographics, personal risk factors, latex exposure assessment, clinical manifestations of latex sensitisation (dermal and respiratory) and history of previous reactions suggestive of LA.

Exposure assessment

Individual exposure

Individual latex exposure was determined by the type of gloves used, number of gloves used per day and duration of glove use. The information was limited to seven working shifts/days prior to the interview.

Departmental exposure

Departmental exposure was defined as glove usage in the past 12 months (1 January–31 December 2011). The overall departmental exposure was obtained by reviewing monthly glove usage by each department from the stock room register. This was used to estimate the annual exposure for employees who had rotated through different departments in the past 12 months. Non-sterile latex gloves are distributed throughout the clinical departments while a high proportion of sterile gloves are distributed to labour wards, theatre, surgical wards and outpatient departments. Glove type was defined as powdered and powder free and latex free based on the previous literature.23 32

Skin prick test

The SPT was conducted using the Stallergenes kit.32 It was performed in a room with access to emergency resuscitation services by a trained research assistant. The research assistant and principal investigator were trained on two separate occasions. The test was performed on the inner aspect of the participant’s forearms, between the wrist and the elbow on normal skin. A positive and negative control were performed using histamine (0.61% concentration of phenol) and buffered normal saline solution, respectively, on the same arm and they were 3 cm apart to prevent cross contamination. The protein concentration of the latex extract was 500 μg/mL and the solution was applied as it was with no further dilutions. After 15–20 min subsequent to puncturing the skin, the SPT reaction wheal and flare was outlined by black ink and clear tape was used to transfer the outline from the skin to the results sheet by the trained research assistant or the principal investigator.33 A positive result was indicated by a mean wheal diameter measuring 3 mm or greater than the negative control. Results were recorded on a standardised result sheet. The research assistant's test performance was audited by the principal investigator at regular intervals to ensure correctness of the technique and interpretation of the results.

Informed signed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to participation. They had the option of participating in the questionnaire interview and the SPT or refusing the SPT. The study protocol was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (BE048/11). Permission to conduct the study was also obtained from the KZN Provincial Department of Health and King Edward VIII hospital management.

Statistical analysis

Data were captured in Excel and analysed in Stata V.11. Frequencies and medians with ranges were presented for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The χ² and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to test for significant associations between categorical and continuous variables and the dependent variables under study on bivariate analysis, respectively.

Logistic regression was used to test for significant associations between independent and dependent variables on multivariate analysis. The dependent variables used in the regression analysis were: latex sensitisation, which was defined as having an SPT wheal of ≥3 mm to latex extract; LA was defined as being SPT positive and a report of having any one or more of the listed work-related clinical symptoms namely itchy eyes, red eyes, runny eyes, runny nose, itchy nose, sneezing, coughing, tight chest, wheezing, itchy skin, skin rash or dizziness. Independent variables that were considered for analysis were as follows: age (years) and sex, duration of employment, job title, current department employed in, type of gloves used, number of pairs of gloves used per day, self reported and family history of atopy, food allergy and history of open surgery and number of surgical procedures. In the multivariate analysis, age was omitted due to collinearity with duration of employment. Departmental glove consumption was omitted as this only indicated annual distribution of gloves per department and not necessarily employee exposure since enrolled nursing assistants and enrolled nurses are rotated through different departments in any given year. The number of pairs of gloves was used as an indicator of individual latex glove exposure. The variable number of pairs of gloves used and duration of employment were retained as continuous variables in the multivariate model. Fractional polynomial and a fractional plot were used to visualise the dose–response relationship of these continuous exposure variables.

Results

Participant demographics

Sixty-five HCWs refused to participate in the study. Among the 520 HCWs who responded to the invitation there was an overall participation rate of 85.5% (n=501) with 3.6% (n=19) refusing SPT. There was no significant difference between those refusing SPT and those who had the SPT with respect to latex exposure status, age, sex and duration of employment.

The median age of participants was 42.2 years (range 22–65 years) with the greater proportion of them being women. The median duration of employment was 10.9 years (range 1–42 years) with the majority of exposed participants having worked as HCW for <10 years. Most unexposed HCWs had been employed for >20 years. Personal and family history of allergy was more prevalent among unexposed HCWs while exposed HCWs reported a higher prevalence of a fruit allergy and history of previous surgery (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and associated risk factors among latex exposed and unexposed healthcare workers at King Edward VIII Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal South Africa (n=501)

| Characteristic | Exposed N (%) | Unexposed N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 337 (67.3) | 164 (32.7) |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤30 | 30 (8.9) | 19 (11.6) |

| >30–40 | 121 (35.9) | 40 (24.4) |

| >40–50 | 101 (29.9) | 59 (35.9) |

| >50 | 85 (25.2) | 46 (28.1) |

| Duration of employment (years) | ||

| ≤5 | 39 (11.6) | 28 (17.1) |

| >5–10** | 135 (40.1) | 32 (19.5) |

| >10–15 | 49 (14.5) | 17 (10.4) |

| >15–20 | 24 (7.1) | 20 (12.2) |

| >20* | 90 (26.7) | 67 (40.9) |

| Sex** | ||

| Female | 309 (91.7) | 95 (57.9) |

| Male | 28 (8.3) | 69 (42.1) |

| Job Title (yes) | ||

| Administrative | 123 (36.5) | 164 (100.0) |

| Professional nurses | 141 (41.8) | |

| Enrolled nurses | ||

| Enrolled nursing assistants | 73 (21.7) | |

| Medical and personal history | ||

| Personal history of allergy disease (yes) | 147 (43.6) | 83 (50.6) |

| Family history of allergy disease (yes) | 197 (58.5) | 102 (62.2) |

| Fruit allergy (yes) | 29 (8.6) | 9 (5.5) |

| Previous open surgery (yes)* | 168 (49.8) | 61 (37.2) |

| Work-related allergy symptoms(yes)* | 138 (40.9) | 52 (31.7) |

| Non-occupational latex exposure (yes) | 161 (47.8) | 76 (46.3) |

| Latex sensitisation (yes) | 24 (7.1) | 5 (3.1) |

| Current latex allergy (yes)* | 20 (5.9) | 3 (1.8) |

χ2, *p<0.05, **p<0.001.

Prevalence of latex sensitisation and allergy

The overall prevalence of latex sensitisation and LA were 5.9% (n=29) and 4.6% (n=23), respectively. Although the difference was not significant, the prevalence of latex sensitisation was higher among the exposed group (7.1%) as compared with the unexposed group (3.1%). LA was significantly higher in the exposed group than the unexposed group (5.9% vs 1.8%, p=0.04). There was a significant difference in the work-related allergy symptoms between exposed and unexposed workers (40.9% vs 31.7%, p=0.04; table 1). Symptoms that were significantly associated with latex sensitisation were skin rash (p<0.000), itchy skin (p=0.001), runny nose (p=0.004), red eyes (p=0.01) and itchy eyes (p=0.01).

The prevalence of latex sensitisation was higher among those who were exposed and those with an employment duration of <10 years. Although the prevalence of latex sensitisation was lower among participants ≤30 years of age, there was no significant variation with age or sex. There was a significant difference (p=0.04) in the prevalence of fruit allergy between those participants with latex sensitisation (17.2%) and unsensitised participants (6.9%) The exclusive use of powder-free latex gloves was found to be significantly (p=0.003) higher among the participants who had latex sensitisation. There was an equal distribution of powdered and powder-free latex gloves among those who reported the use of mixed gloves. The prevalence of reporting previous open surgery and use of other non-occupational exposure latex containing material did not vary significantly between those who had latex sensitisation and those who were unsensitised. There was a significantly higher prevalence of reporting allergic reactions when handling other latex containing medical equipment among participants with LA as compared with unsensitised participants (10.3% vs 1.7%, p=0.002; table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of risk factors between latex sensitised (skin prick test positive) and non-sensitised (skin prick test (APT) negative) healthcare workers at King Edward VIII Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal South Africa (n=501)

| Characteristics | Latex SPT positive† (29) N (%) | Latex SPT negative‡ (472) N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤30 | 1 (3.5) | 48 (10.2) |

| >30–40 | 13 (44.8) | 148 (31.4) |

| >40–50 | 8 (27.6) | 152 (32.2) |

| >50 | 7 (24.1) | 124 (26.3) |

| Duration of employment | ||

| ≤5 | 3 (10.3) | 64 (13.6) |

| >5–10 | 16 (55.2) | 151 (31.9) |

| >10–15 | 3 (10.3) | 63 (13.4) |

| >15–20 | 1 (3.5) | 43 (9.1) |

| >20 | 6 (20.7) | 151 (31.9) |

| Sex (yes) | ||

| Male | 5 (17.2) | 118 (25.0) |

| Female | 24 (82.8) | 354 (75.0) |

| Job title (yes) | ||

| Administrative | 5 (17.2) | 159 (33.7) |

| Professional nurses | 5 (17.2) | 118 (25.0) |

| Enrolled nurses | 14 (48.3) | 127 (26.9) |

| Enrolled nursing assistants | 5 (17.2) | 68 (14.4) |

| Latex exposure | ||

| Exposure status (yes) | 24 (82.8) | 313 (66.3) |

| Type of gloves | ||

| None | 5 (17.2) | 165 (34.6) |

| Exclusive powdered latex glove (yes) | 2 (6.9) | 36 (7.6) |

| Exclusive powder-free latex glove (yes)* | 11 (37.9) | 77 (16.3) |

| Mixed (yes) | 11 (37.9) | 198 (41.9) |

| Medical and personal history | ||

| Personal history of allergy disease (yes) | 16 (55.2) | 214 (45.3) |

| Family history of allergy disease (yes) | 18 (62.1) | 281 (59.5) |

| Fruit allergy (yes)* | 5 (17.2) | 33 (6.9) |

| Previous open surgery (yes) | 18 (62.1) | 211 (44.7) |

| Non-occupational latex exposure (yes) | 12 (41.4) | 225 (47.7) |

| Reaction to other latex medical devices (yes)* | 3 (10.3) | 8 (1.7) |

χ2, *p<0.05.

†Latex skin prick test positive.

‡Latex skin prick test positive and work-related clinical symptoms of allergy.

Crude association of demographics, exposure status, medical and personal history and latex sensitisation, LA

Latex exposure was significantly associated with LA (OR 3.4; 95% CI 1.1 to 10.8). Working as HCW for 5–10 years was significantly associated with latex sensitisation (OR 2.6; 95% CI 1.2 to 5.5) and LA (OR 3.3; 95% CI 1.4 to 7.6), respectively. Employment duration as HCW for >20 years was protective against LA (OR 0.2; 95% CI 0.0 to 0.8). In comparison with unexposed workers, working as an enrolled nurse was significantly associated with both latex sensitisation (OR 2.5; 95% CI 1.2 to 5.3) and LA (OR 2.4; 95% CI 1.1 to 5.6). The exclusive use of powder-free latex gloves was significantly associated with latex sensitisation (OR 3.1; 95% CI 1.4 to 6.8) and LA (OR 3.1; 95% CI 1.7 to 9.1). Powdered and powder-free latex gloves were equally distributed among those who reported the use of mixed gloves. The annual consumption of pairs of gloves per HCW by department was ranked and grouped into tertiles. Although medical and surgical wards had low and moderate pairs of gloves consumption per HCW, these wards had the highest proportion of workers with latex sensitisation (n=6, 20% each). However the relation was only significant for those who reported the medical ward as being the current department in which they worked (p=0.01). The proportions for powdered latex glove use were 71% and 69% in medical and surgical wards, respectively, and this was not statistically significant. Exposure to other latex containing medical devices was not significantly different from what was reported in other wards. There was no significant association between reported personal history of allergy disease, latex sensitisation and LA. Fruit allergy was significantly associated with LA (OR 3.7; 95% CI 1.4 to 10.4; table 3). Listed fruits were evaluated for their independent association with latex sensitisation. Avocado (OR 12.3; 95% CI 5.1 to 29.6) and others (OR 5.1; 95% CI 2.1 to 11.8) which included pineapple and orange showing significant associations with latex sensitisation (data not shown).

Table 3.

Crude ORs (95% CI) of demographics, exposure status, medical and personal history and latex sensitisation and latex allergy among healthcare workers at King Edward VIII Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal South Africa, (n=501)

| Characteristics | N=29 | Latex sensitisation OR‡ (95% CI) | N=23 | LA† OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤30 | 1 | 0.3 (0.0 to 1.9) | 1 | 0.4 (0.0 to 2.4) |

| >30–40 | 13 | 1.8 (0.8 to 3.7) | 11 | 2.0 (0.9 to 4.6) |

| >40–50 | 8 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.8) | 7 | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.2) |

| >50 | 7 | 0.8 (0.4 to 2.1) | 4 | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.7) |

| Duration of employment (years) | ||||

| <5 | 3 | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.4) | 3 | 0.9 (0.3 to 3.2) |

| 5–10 | 16 | 2.6 (1.2 to 5.5)* | 14 | 3.3 (1.4 to 7.6)* |

| >10–15 | 3 | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.4) | 3 | 0.9 (0.3 to 3.2) |

| >15–20 | 1 | 0.4 (0.0 to 2.1) | 1 | 0.5 (0.0 to 2.8) |

| >20 | 6 | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.4) | 2 | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.8)* |

| Sex (yes) | ||||

| Female | 24 | 1.6 (0.6 to 4.1) | 20 | 2.2 (0.7 to 7.2) |

| Job title (yes) | ||||

| Administrative | 5 | 0.4 (0.2 to 1.1) | 3 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.9)* |

| Professional nurses | 5 | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.6) | 4 | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.8) |

| Enrolled nurses | 14 | 2.5 (1.2 to 5.3)* | 11 | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.6)* |

| Enrolled nursing assistants | 5 | 1.2 (0.5 to 3.3) | 5 | 1.7 (0.6 to 4.5) |

| Latex exposure | ||||

| Exposure status (yes) | 24 | 2.4 (0.9 to 6.3) | 20 | 3.4 (1.1 to 10.8)* |

| Type of gloves | ||||

| None | 5 | 0.4 (0.2 to 1.0) | 3 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.9)* |

| Exclusive Powdered latex glove (yes) | 2 | 0.9 (0.0 to 3.6) | 2 | 1.2 (0.0 to 1.7) |

| Exclusive Powder-free latex glove (yes) | 11 | 3.1 (1.4 to 6.8)* | 10 | 3.1 (1.7 to 9.1)* |

| Mixed gloves (yes) | 11 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.8) | 8 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.7) |

| Medical and personal history | ||||

| Personal history of allergy disease (yes) | 16 | 1.4 (0.7 to 3.1) | 12 | 1.3 (0.5 to 2.9) |

| Family history of allergy disease (yes) | 18 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.4) | 14 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.4) |

| Fruit allergy (yes) | 5 | 2.8 (1.0 to 7.5) | 5 | 3.7 (1.4 to 10.4)* |

| Previous open surgery (yes) | 18 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.4) | 14 | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.1) |

χ2, *p<0.05.

†Latex skin prick test positive and work-related clinical symptoms of allergy.

‡Latex skin prick test positive.

LA, latex allergy.

Multivariate analysis

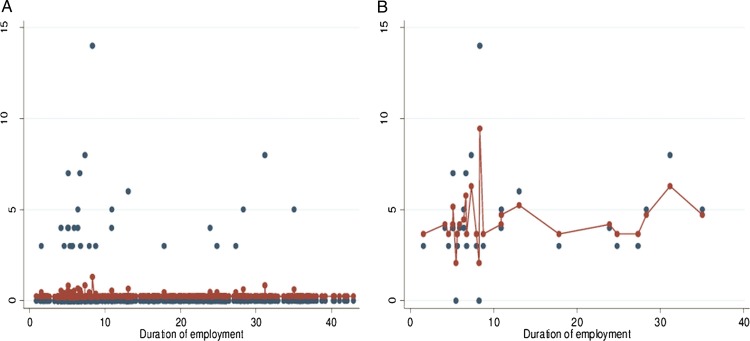

While latex exposure had estimates of the OR above 2, there was no significant association with latex sensitisation and LA. Duration of employment was found to be inversely associated with LA in models I and II. The exclusive use of powder-free latex gloves was significantly associated with latex sensitisation (OR 4.2; 95% CI 1.2 to 14.1) and LA (OR 5.1; 95% CI 1.2 to 21.2) on multivariate analysis. This significant association disappeared when examining the number of pairs of powder-free gloves used in the last 7 days. A weak association was observed for the number of pairs of powdered latex gloves used in the last 7 days with both latex sensitisation and LA (models III and IV). Further analysis of duration of employment and number of pairs of gloves using fractional polynomial failed to demonstrate a significant dose–response relationship with either latex sensitisation or LA. Duration of employment showed a significant (p=0.000) dose–response relationship when analysed using penalised spline with degree of freedom=2 (figure 1). There was a significant association between fruit allergy and LA in model I (OR 3.1; 95% CI 1.1 to 9.2; table 4).

Figure 1.

Exposure–response relationship between duration of employment and latex sensitisation using penalised splines including (A) all participants and (B) skin prick test positive only.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of demographics, medical and personal history, exposure history and latex sensitisation (LS)* and latex allergy (LA)† among healthcare workers at King Edward III Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal South Africa (n=501)

| Characteristics| | Model I‡ (n=501) |

Model II§ (n=501) |

Model III¶ (n=202) |

Model IV**(n=252) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS OR (95% CI) |

LA OR (95% CI) |

LS OR (95% CI) |

LA OR (95% CI) |

LS OR (95% CI) |

LA OR (95% CI) |

LS OR (95% CI) |

LA OR (95% CI) |

|

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Sex (female) | 0.9 (0.2 to 2.7) | 1.1 (0.3 to 4.4) | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.7) | 1.1 (0.3 to 4.5) | 0.3 (0.0 to 1.8) | 0.3 (0.0 to 3.1) | 2.5 (0.5 to 12.2) | 2.5 (0.5 to 12.2) |

| Duration of employment (years) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.8) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) |

| Latex exposure | ||||||||

| Exposure status (yes) | 2.2 (0.7 to 6.7) | 2.6 (0.7 to 9.8) | ||||||

| Type of gloves | ||||||||

| None | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Exclusive lightly powdered latex glove (yes) | 1.6 (0.3 to 9.8) | 2.6 (0.4 to 17.7) | ||||||

| Exclusive powder-free latex glove (yes) | 4.2 (1.2 to 14.1) | 5.1 (1.2 to 21.2) | ||||||

| Mixed gloves (yes) | 1.7 (0.5 to 5.6) | 1.7 (0.4 to 7.1) | ||||||

| Pairs of powdered latex gloves in the last 7 days | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | ||||||

| Pairs of powder-free latex gloves in the last 7 days | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | ||||||

| Personal and medical history | ||||||||

| Personal history of allergy disease (yes) | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.3) | 1.4 (0.6 to 3.2) | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.3) | 1.3 (0.6 to 3.2) | 1.4 (0.3 to 6.8) | 1.6 (0.2 to 11.6) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.9) | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.8) |

| Family history of allergy disease (yes) | 1.0 (0.45 to 2.2) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.2) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.3) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.3) | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.9) | 0.5 (0.1 to 3.6) | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.0) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.7) |

| Fruit allergy (yes) | 2.3 (0.8 to 6.7) | 3.1 (1.1 to 9.2) | 2.2 (0.8 to 6.5) | 3.0 (0.9 to 9.1) | 5.0 (0.4 to 56.9) | 9.7 (0.6 to 163.0) | 1.7 (0.3 to 8.5) | 2.0 (0.4 to 10.4) |

| Previous open surgery (yes) | 2.0 (0.9 to 4.4) | 1.9 (0.8 to 4.6) | 2.1 (0.9 to 4.6) | 1.9 (0.8 to 4.7) | 1.4 (0.3 to 7.4) | 1.2 (0.1 to 11.1) | 1.1 (0.4 to 3.2) | 1.2 (0.4 to 3.8) |

*Latex skin prick test positive.

†Latex skin prick test positive and work-related clinical symptoms of allergy.

‡Model included latex glove exposure status.

§Model included type of gloves.

¶Model included number of pairs of powdered latex gloves.

**Model included number of pairs of powder-free latex gloves.

Discussion

This is an important study for South African HCWs as it examined the risk of latex sensitisation in a group of workers exposed to hypoallergenic latex gloves. As previously mentioned there has been no literature documenting the prevalence of latex sensitisation among South African HCWs using hypoallergenic lightly powdered or powder-free latex gloves. The prevalence of latex sensitisation among exposed HCWs (7.1%) in this study is comparable to findings among HCWs in another South African hospital.14 However, it was considerably lower than the 11.9% prevalence reported by Potter in the same year.16 While a substantial number of participants (37%) reported work-related allergy symptoms, only 4.6% met our definition of LA. The important symptoms associated with latex sensitisation were skin rash, itchy skin, runny nose, red and itchy eyes in keeping with previous studies. The elimination of powdered latex gloves has shown a reduction in the concentration of aeroallergens in the operating room with the low prevalence of LA in our study population.

Although the relationship was weak, this study showed that the risk of latex sensitisation decreases with duration of employment. The healthy worker effect is a likely explanation of this finding. Prior to the availability of hypoallergenic latex gloves, workers who had developed LA may have left their employment or they may have changed their career path and moved into a more administrative or managerial role with no contact with latex gloves. Furthermore new employees are only sensitised and have not yet manifested clinical symptoms and they continue using latex gloves. On the other hand senior HCWs may have been sensitised during their earlier years of employment and as a result they either moved to departments with less exposure to latex gloves or deliberately avoid latex containing products and therefore exhibit less latex-related symptoms. Moreover, the introduction of hypoallergenic gloves 10 years prior to the study may explain the reduced sensitisation in senior HCWs as demonstrated in the study by Smith et al in 2007. The published literature has been inconsistent in reporting the association between duration of employment and latex sensitisation. Although latex is one of the best studied allergens, no exposure response studies have been published with measured latex allergen levels. In addition, studies have demonstrated a variation in the allergen content of different gloves. These may lead to discrepancies in the literature with regard to the role of duration of employment as a surrogate measure of exposure.

In our study HCWs who exclusively used powdered free latex gloves had a four times greater odds of developing latex sensitisation. The fact that HCWs with latex sensitisation or allergy work more often with powder-free latex gloves is indicative of reverse causality because of symptoms. Moreover the background prevalence of latex sensitisation in this study was relatively higher (3.5%) than the previously reported prevalence in the general population by Bousquet et al.13 Studies have shown that some of these ‘hypoallergenic’ latex gloves actually contain high levels of allergens which can be released into the environment with aggressive manipulation.23 Some of the sensitised HCWs may have been sensitised before the hospital implemented a hypoallergenic latex glove policy. Also Smith et al34 showed that complete avoidance of powdered latex glove can result in the reduction or no change in measurable IgE antibodies. A study in Germany reported a high prevalence of 8% among 226 dental students who had only been exposed to exclusive powder-free latex gloves.30 Similarly in the UK despite a total ban on powdered latex gloves Clayton and Wilkinson31 found a 10% prevalence of latex sensitisation in HCWs. It is also not clear to what extent the aeroallergens released by colleagues using powdered latex gloves influence this finding. Furthermore the role of other latex containing medical devices during the sensitisation period cannot be entirely ruled out.

In our study, the frequency of exposure as measured by the number of gloves used in the last seven working days showed a weak association between powdered latex gloves and latex sensitisation but no association could be demonstrated with powder-free latex gloves. Airborne latex aeroallergens have been shown to increase with the number of powdered gloves used which subsequently increases the risk of latex sensitisation and clinical latex glove-related allergy symptoms.18

The positive association between departments with low glove consumption per HCW and latex sensitisation is in contrast with a previous finding by Liss et al.9 They reported a positive association with departments that had high glove consumption per HCWs. Again, this could be as a result of reverse causality where HCWs with latex sensitisation may have been relocated to wards with low glove consumption to minimise the exposure. In addition, the annual pair of gloves consumption per HCW by department does not provide an accurate indication of individual exposure; rather it gives us the annual distribution of gloves to different departments.

Several studies have reported atopy as a significant risk factor for latex sensitisation.9 10 35 Similarly, the prevalence of reporting a history of personal atopy in this study was higher among latex sensitised participants although the association was not statistically significant. The role of atopy is complex because some individuals might also have become atopic after having been latex sensitised and a cross-sectional study is not suitable in establishing this association.

Fruit LA syndrome is a phenomenon seen where latex-sensitised individuals demonstrate a cross reactivity with specific foods; particularly fruits. Studies have identified this phenomenon among sensitised HCWs and the general population. This has been attributed to the similarity between fruit proteins and latex allergens.36 Fruit allergy was significantly associated with latex sensitisation and LA in our study. Our study was dependent on the self-reporting of fruit allergy and no objective tests were carried out. It is therefore possible that participants have independent simultaneous allergies to both fruit and latex without cross reactivity. Also, we were unable to determine whether latex sensitisation preceded the development of fruit allergy or vice versa. Fruit allergy prior to latex exposure could have contributed to the association observed in our study.

Latex sensitised participants reported a high prevalence of a history of previous open surgery in our study. This has been reported to occur as a result of direct intraoperative exposure to latex containing medical devices such as catheters or tubes. Studies in children with congenital abnormalities have demonstrated that the risk for LA increases with the number of open surgical procedures that they undergo.37 Frequency of invasive procedures among adults was shown to increase the risk of latex sensitisation reporting while more than 10 procedures increased the risk of developing LA.38

The strengths of this study include the high response rate (85.5%) and comparability to other studies.8 16 Access to the hospital employee database allowed us to better assess the representativeness of this study population by comparing the demographic data of the non-participants and the participants. The participants were randomly selected minimising the potential of participant bias that comes with a volunteer approach.

The presence of a control group provided a background prevalence of latex sensitisation in this population which allowed for a better estimation of associations attributable to work-related factors. The use of Stallergenes latex specific SPT further strengthens the study. The SPT test is regarded as the gold standard for the diagnosis of LA and Stallergenes has been shown to have a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 100%, respectively.32 The research assistant employed on this study was trained and initially shadowed and periodically supervised by the principal investigator to ensure appropriate administration of the questionnaire and the SPT thereby improving the reliability and validity of the study.

This study was limited by the cross-sectional study design which was relatively low in cost and quick to conduct. It only allowed for the determination of prevalence of latex sensitisation at one point in time. Consequently the prevalence of latex sensitisation may have been underestimated as it is possible that HCWs who had already developed latex sensitisation have left the hospital before the study was conducted. Some of the observed associations in the study may be as a result of a complex interplay between the healthy worker effect, reverse causality and exposure reduction by the introduction of powder-free latex gloves. These interactions can be better explored and understood in a longitudinal study. Recall bias is another potential limitation in this study as workers were asked to recall the number of gloves used in the past seven working days. HCWs may have overestimated or underestimated their individual exposures. Our study depended on the self-reporting of personal and family atopic disorders and this may have resulted in the misclassification of atopy. The role of atopy and cross reactivity between allergens is a complex phenomenon which cannot be investigated in a cross-sectional study. Therefore, cohort studies are necessary to disentangle this phenomenon.

Conclusion

This study shows that even in the presence of powder-free hypoallergenic glove use there is latex sensitisation and LA, adding to previous findings that HCWs exposed to hypoallergenic latex gloves are still at risk for developing latex sensitisation and LA. This indicates that latex sensitisation and allergy are still an important occupational hazard for HCWs. While it may be economically impractical to replace the latex gloves in our setting, a reduction of the allergen content in latex products is another strategy that can be implemented to address the problem and protect HCWs. A policy accompanied by clear implementation plans as well as sustainable education and training programmes to address latex sensitisation and allergy among HCWs should be implemented.39 In addition HCWs must be continuously monitored for the development of latex sensitisation and alternate latex-free gloves must be made available for them. More research is needed to identify the most cost effective way of implementing a latex-free environment in resource-limited countries, such as South Africa. In addition the current studies in South Africa have largely been cross-sectional in nature. More cohort analyses is required to better understand the chronicity of illness and disability associated with LA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the hospital employees participating in this study and their management for allowing access to the human resource database. The authors would like to thank Professor Mohamed Jeebhay (Centre of Occupational and Environmental Health, University of Cape Town, SA) and Professor David L Nordstrom (Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health, University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, USA) for their comments on the initial proposal. The authors would like to thank Professor Rajen Naidoo (Discipline of Occupational and Environmental Health, UKZN, SA) for his statistical advice during the data analysis, and his writing/editing of the article. In addition, to the authors would like to thank Mr Nhlanhla Jwara for conducting the field work.

Footnotes

Contributors: SMP is the principal investigator who was involved in the conception of the idea, proposal writing, data collection, data management and interpretation of the results. SN contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical review of the intellectual content of the article and final approval of the article.

Funding: This research received R20000 Grant from the College of Health Science, University of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Biomedical Research Ethics Committee- University of KwaZulu Natal.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nutter AF. Contact urticaria to rubber. Br J Dermatol 1979;101:597–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control Recommendations for prevention of HIV transmission in health-care settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1987;36(Suppl 2):1S–18S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rego A, Roley L. In-use barrier integrity of gloves: latex and nitrile superior to vinyl. Am J Infect Control 1999;27:405–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung R, Ho A, Chan J, et al. Prevalence of latex allergy in hospital staff in Hong Kong. Clin Exp Allergy 1997;27:167–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaiear N, Jindawong B, Boonsawas W, et al. Glove allergy and sensitization to natural rubber latex among nursing staff at Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thailand 2006;89:368–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan KS, Lue HC. Latex allergy in health care workers in Taiwan: prevalence, clinical features. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2007;80:455–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas R, Morton J, Czarny D, et al. Prevalence of IgE-mediated allergy to latex in hospital nursing staff. Aust N Z J Med 1997;27:165–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grzybowski M, Ownby DR, Peyser PA, et al. The prevalence of anti-latex IgE antibodies among registered nurses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;98:535–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liss GM, Sussman GL, Deal K, et al. Latex allergy: epidemiological study of 1351 hospital workers. Occup Environ Med 1997;54:335–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts DN, Jacobs RR, Forrester B, et al. An evaluation of the prevalence of latex sensitivity among atopic and non-atopic intensive care workers. Am J Ind Med 1998;34:359–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verna N, Di Giampaolo L, Renzetti A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for latex-related diseases among healthcare workers in an Italian general hospital. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2003;33:184–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porri F, Lemiere C, Birnbaum J, et al. Prevalence of latex sensitization in subjects attending health screening: implications for a perioperative screening. Clin Exp Allergy 1997;27:413–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bousquet J, Flahault A, Vandenplas O, et al. Natural rubber latex allergy among health care workers: a systematic review of the evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118:447–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brathwaite N, Motala C, Toerien A, et al. Latex allergy—the Red Cross Children's Hospital experience. S Afr Med J 2001;91:750–1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Beers C, Cilliers J. Accurate diagnosis of latex allergy in hospital employees is cost-effective. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;91:760–5 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potter PC, Crombie I, Marian A, et al. Latex allergy at Groote Schuur Hospital—prevalence, clinical features and outcome. S Afr Med J 2001;91:760–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Labour Compensation of Occupational and Diseases Act no 130. South Africa: Pretoria, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allmers H, Brehler R, Chen Z, et al. Reduction of latex aeroallergens and latex-specific IgE antibodies in sensitized workers after removal of powdered natural rubber latex gloves in a hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;102:841–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wrangsjo K, Boman A, Liden C, et al. Primary prevention of latex allergy in healthcare-spectrum of strategies including the European glove standardization. Contact Dermatitis 2012;66:165–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malerich PG, Wilson ML, Mowad CM. The effect of a transition to powder-free latex gloves on workers’ compensation claims for latex-related illness. Dermatitis 2008;19:316–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baur X, Chen Z, Allmers H. Can a threshold limit value for natural rubber latex airborne allergens be defined? J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;101:24–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes BB, Afshari A, Millecchia L, et al. Evaluation of percutaneous penetration of natural rubber latex proteins. Toxicol Sci 2000;56:262–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mabe DO, Singh TS, Bello B, et al. Allergenicity of latex rubber products used in South African dental schools. S Afr Med J 2009;99:672–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaMontagne AD, Radi S, Elder DS, et al. Primary prevention of latex related sensitisation and occupational asthma: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 2006;63:359–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heederik D, Henneberger PK, Redlich CA. et al. Primary prevention: exposure reduction, skin exposure and respiratory protection. Eur Respir Rev 2012;21:112–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baur X, Sigsgaard T. The new guidelines for management of work-related asthma. Eur Respir J 2012;39:518–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potter PC. Latex allergy—time to adopt a powder-free policy nationwide. S Afr Med J 2001;91:746–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liss GM, Tarlo SM. Natural rubber latex-related occupational asthma: association with interventions and glove changes over time. Am J Ind Med 2001;40:347–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt LW, Kelkar P, Reed CE, et al. Management of occupational allergy to natural rubber latex in a medical center: the importance of quantitative latex allergen measurement and objective follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;110:S96–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmid K, Christoph Broding H, Niklas D, et al. Latex sensitization in dental students using powder-free gloves low in latex protein: a cross-sectional study. Contact Dermatitis 2002;47:103–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clayton TH, Wilkinson SM. Contact dermatoses in healthcare workers: reduction in type I latex allergy in a UK centre. Clin Exp Dermatol 2005;30:221–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turjanmaa K, Palosuo T, Alenius H, et al. Latex allergy diagnosis: in vivo and in vitro standardization of a natural rubber latex extract. Allergy 1997;52:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris A. ALLSA position statement: allergen skin-prick testing. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;90:22–5 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith AM, Amin HS, Biagini RE, et al. Percutaneous reactivity to natural rubber latex proteins persists in health-care workers following avoidance of natural rubber latex. Clin Exp Allergy 2007;37:1349–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suli C, Parziale M, Lorini M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for latex allergy: a cross sectional study on health-care workers of an Italian hospital. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2004;14:64–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blanco C. Latex-fruit syndrome. Cur Allergy Asthma Rep 2003; 3:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porri F, Pradal M, Lemiere C, et al. Association between latex sensitization and repeated latex exposure in children. Anesthesiology 1997;86:599–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rueff F, Kienitz A, Schopf P, et al. Frequency of natural rubber latex allergy in adults is increased after multiple operative procedures. Allergy 2001;56:889–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown RH, Hamilton RG, McAllister MA. How health care organizations can establish and conduct a program for a latex-safe environment. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2003;29:113–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.