Abstract

Background. In Ethiopia the prevalence of all forms of TB is estimated at 261/100 000 population, leading to an annual mortality rate of 64/100 000 population. The incidence rate of smear-positive TB is 108/100 000 population. Objectives. To assess knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding TB among pastoralists in Shinille district, Somali region, Ethiopia. Method. A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 821 pastoralists aged >18 years and above from February to May, 2011 using self-structured questionnaire. Results. Most (92.8%) of the study participants heard about TB, but only 10.1% knew about its causative agent. Weight loss as main symptom, transmittance through respiratory air droplets, and sputum examination for diagnosis were the answers of 34.3%, 29.9%, and 37.9% of pastoralists, respectively. The majority (98.3%) of respondents reported that TB could be cured, of which 93.3% believed with modern drugs. About 41.3% of participants mentioned covering the nose and mouth during sneezing and coughing as a preventive measure. The multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that household income >300 Ethiopian Birr and Somali ethnicity were associated with high TB knowledge. Regarding health seeking behaviour practice only 48.0% of the respondents preferred to visit government hospital and discuss their problems with doctors/health care providers. Conclusion. This study observed familiarity with gaps and low overall knowledge on TB and revealed negative attitudes like discrimination intentions in the studied pastoral community.

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis continues to be one of the most important global public health threats. About one-third of the world's population is estimated to be infected with tubercle bacilli and hence at risk of developing active disease. TB is a leading killer of people with HIV. According to the World Health Organization Global TB Report [1], in 2010 there were approximately 8.8 million incident cases of TB globally, of which 1.1 million were among people living with HIV. The disease has been recognized as major public health problem in Ethiopia including Somali regional state and in 2010 there were estimated 220,000 (261/100,000) incident cases of TB, estimated 29,000 deaths (35/100,000) excluding HIV-related mortality [1]. As per Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) data, TB in Ethiopia was one of the leading causes of morbidity, the fourth main cause of hospital admission, and the second largest cause of hospital deaths (after malaria) [2]. According to the Somali Regional Health Bureau Report [3], the annual incidence rate during 2008 of smear-positive PTB was 175−250/100,000/year which was higher than the national figure of 165/100,000. The disease is one of the top ten causes of outpatient visit, hospital admission and death in the region. Furthermore, the emergence of multidrug resistant TB (MDR-TB) has become a major public health problem in a number of countries and an obstacle to global TB control [4, 5]. Ethiopia is one of the 27 high burden MDR-TB countries ranking 15th with more than 5000 estimated MDR-TB patients annually [2].

Pastoralists are the seminomadic people whose livelihood largely depends on livestock raising. An estimated 50–100 million pastoralists live in the developing world of which 60% are in sub-Saharan Africa. In the Horn of Africa, pastoralists constitute 70% of the general population, of which 12% is in Ethiopia [6]. The majority of these pastoralists live in the southeastern and northeastern Somali region of the country having three different livelihood systems, that is, pastoralism, agropastoralism, and urban. Pastoralists and agro-pastoralists both constitute about 85%, while the rest was urban. Due to their mobile lifestyle, pastoralists often stay in border areas and highly volatile and insecure environments that were often beyond the reach of formal health services including TB control programs [7]. Pastoralists in Shinille district of Somali region of Ethiopia were confined to the most arid part of the country. Being geographically isolated in remote rural areas with poor infrastructure and communication, they are considered to be underserved and deprived of all forms of health care and are perceived as of low priority. Work environment, poverty, and lack of awareness are important factors affecting the health seeking behavior and the control strategies. Previously, a study was conducted in the area to explore barriers delaying TB diagnosis among pastoralist TB patients. The study revealed that factors related to sociocultural, perceptions of TB, and pastoralists' limited access to health care are the key factors leading to an apparent delay in diagnosis of pastoralist TB patients [7]. Tuberculosis is still a problem in the area and further high notification rate poses a challenge. Since the perception of pastoralist community in the region, particularly in Shinille district, towards TB has not been well investigated, assessing the baseline information regarding knowledge, attitudes, and practices on TB will offer a good insight about the overall picture of the control activity in the region and thereby assist in the development of a strategy for improving quality of service.

2. Methods

Somali region (state) is the eastern-most of the nine ethnic divisions of Ethiopia. The capital of Somali State is Jijiga. Shinille, the largest of four districts in Shinille Zone which is located in the Somali Region, has a latitude and longitude of 09°41′N and 41°51′E with an elevation of 1079 meters above sea level. The region borders are Kenya to the south-west, the Ethiopian regions of Oromia, Somali, and Dire Dawa to the west, Djibouti to the north, and Somalia to the north, east, and south. The region is among the areas of the country sparsely populated with an average population density of about 15 persons per km2. The region is remote with a mobile nomadic population and inadequate infrastructure. Climatically, it is mostly desert with high average temperatures and low bimodal rainfall. Its economy is weak and reliant predominantly on traditional animal husbandry and marginal farming practices. Shinille district has an estimated total population of 13,132, of whom 6,758 were males and 6,374 were females according to Central Statistical Agency [8]. The two largest ethnic groups reported in the district were the Somali (96.58%) and the Oromo (1.76%), while all other ethnic groups made up the remaining 1.66% of the residents [8]. The major type of activity in population is pastoralism (48%) followed by crop farming (25%) and agropastoralism (17%).

A community-based cross-sectional survey was carried out from February to May 2011. The study population was the heads of pastoralist households with age above 18 years and residing in the study area. As per custom the heads of the family interact first with the society, community, and other visitors and are assumed to have more exposure and knowledge about social and health issues. Household heads having sickness, speaking and hearing problems were exempted from the study. In the absence of the family heads, the other eldest male or female member of the family was selected for the interview. The required sample of 852 household heads was determined using sample size calculation formula for single population proportion [9], with 95% confidence level, and 49.1% assumed prevalence of overall knowledge on TB according to a similar study done on pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) in Arbaminch area of Ethiopia [10]. The study subjects were selected using cluster sampling technique. For cluster sampling, a design effect of 2 was applied and 10% was added for nonresponse rate accordingly for total sample size calculation. Shinille district has 28 villages and each village is considered as one cluster making a total of 28 clustered villages. Villages were selected randomly to represent the whole population and all households within the selected clusters were included in the sampling. Finally, from each housing unit the household head was selected for the interview. Pastoralists in the region are known to be ethnically and culturally a closely homogeneous group of people, who share one language, religion, and lifestyle. For such a closely homogeneous people by using cluster sampling technique, 852 household heads were deemed an adequate sample size to create the intended quantitative product. In addition because of scattered settlement of the communities on the vast areas of the region it can be expensive to survey. Treating several respondents within a local area as a cluster, finally all participants in the cluster were selected for Interview.

The data were collected by face-to-face interviews using self-structured and pretested questionnaires. The questionnaires were prepared by consulting the literature and modified to fit the local context. The questionnaire was first developed in English and then translated into Somali (local language), and back to English by a different individual to check consistency and conceptual equivalence. Included in the questionnaire were sociodemographic questions (age, sex, education, marital status, occupation, family size, monthly family income, and housing conditions), knowledge on TB causes, symptoms, diagnostic methods, transmission, prevention, treatment, and seriousness of disease, attitudes and practices intended health seeking behaviour, and information sources. Eight trained data collectors and one supervisor having good command on local language were involved in data collection. Prior to data collection, the objective of the study was discussed including practical exercise with data collectors and health education was provided regarding precautionary measures during data collection. An interview guide was also provided to data collectors and supervision was made by one of the authors during data collection process for timely edition of the data and feedback.

One of the authors coordinated the data collection process and rechecked the filled questionnaires. Pretesting of the questionnaire was conducted in Error woreda (block) village. During the pretest, the questionnaire was assessed for its clarity, understandability, completeness, reliability, as well as sensitivity of the subject matter. Corrections were made for difficulties and interview time was determined for completing each questionnaire.

The ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Gondar. Permission was also obtained from Somali Regional State and from administrative bodies of the district including kebeles (wards). Verbal consent was obtained from each respondent after explaining the confidentiality and voluntary participation features of the study. Moreover, the study questionnaire was anonymous and interview was conducted in a private setting to maintain privacy of the respondents for sensitive questions. Objectives of the study were explained to the respondents prior to the administration of the interview and confidentiality was maintained by omitting name of the respondents.

Complete data was entered and analyzed using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 for windows statistical program. Results were summarized using descriptive statistics and presented by frequency tables, percentage, and charts. Association was computed between knowledge and sociodemographic variables using bivariate and multivariate analysis techniques. Logistic regression was done to assess the associations of factors with tuberculosis knowledge. The significance of associations are presented using P values and the 95% confidence interval of the adjusted odds ratios (AOR).

Overall, knowledge on TB was assessed using questions such as causes of TB, symptoms, diagnostic methods, transmission, prevention, treatment, and seriousness of disease. The responses to these questions were added together and scored for every study participant; the composite score was dichotomized using mean as a cut-off value. A score of one was assigned to correct responses, nil for incorrect/do not know answers. Afterwards, scores above the mean value were categorized under high knowledge and those below the mean value were labelled as having low knowledge on TB. The mean score was taken as the cut-off value and those scored above were categorised in having high TB knowledge. The mean and the median scores were 5.42 and 5.51, respectively. Similarly, attitudes, practices, and intended health seeking behaviour were assessed. Respondents attitude was measured by questionnaire containing two options of agree and disagree. Questions include were they feel ashamed if some of their relative/family member gets infected with TB, want to keep secrete if they have TB, afraid of TB patients due to their illness, having belief that getting TB is a punishment for sinful act, continue friendship if their friends has TB, willing to provide care to their relative suffering from TB, might allow their daughter/son to marry cured TB patient.

3. Results and Discussion

A total of 852 respondents aged ≥18 years were selected for this study. Out of this, 2.8% refused to participate while 0.82% could not be available for the interview after two attempts. Lack of interest was the reason for those who refused to participate. Therefore, the data was collected from 821 study subjects out of whom 51.6% were males and 48.4% were females with a response rate of 96.36%.

The highest proportion (30.1%) of the study subjects was within the age group of 25–34 years, and the least proportion (3.5%) was ≥55 years. Majority of the respondents were married (81.0%), while 13.2% were single, and 2.3%, 2.1%, and 1.5% were widowed, separated, and divorced, respectively. More than half of the households (55.2%) had a mean family size of 5. Regarding the occupation of the interviewee, pastoralists were dominant (43.8%), followed by cattle keepers and farmers (34.2%), agro-pastoralists (20.1%), and the rest (1.8%) included merchants, Quran tutors, and shop keepers (Table 1). Regarding pastoralists' education, 62% were illiterate, that is, cannot read and write. Around 34% can read and write, while 3.9% and 0.2% had 1–8 and 9–12 standard education, respectively. All of the study subjects were Muslims and a substantial amount (94.5%) identified themselves with the Somali Ethnic group and the rest (5.5%) with Oromo ethnicity. The median monthly income of the families was between 100 and 300 Birr (Ethiopian currency) approximately equivalent to 5.88–17.65 US$.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population (n = 821).

| Background Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 424 (51.6) |

| Female | 397 (48.4) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–24 | 197 (24.0) |

| 25–34 | 247 (30.1) |

| 35–44 | 212 (25.8) |

| 45–54 | 127 (15.5) |

| >55 | 29 (3.5) |

| Do not know | 9 (1.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Somali | 776 (94.5) |

| Oromo | 45 (5.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 665 (81.0) |

| Single | 108 (13.2) |

| Separated | 12 (1.5) |

| Divorced | 17 (2.1) |

| Widowed | 19 (2.3) |

| Occupation | |

| Pastoralist | 360 (43.8) |

| Agro pastoralist | 165 (20.1) |

| Cattle keeping and farming | 281 (34.2) |

| Others* | 15 (1.8) |

| Education | |

| Cannot read and write | 509 (62.0) |

| Read and write | 278 (33.9) |

| Grade 1–8 | 32 (3.9) |

| Grade 9–12 | 02 (0. 2) |

| Religion | |

| Muslim | 821 (100) |

| Household income | |

| Less than 100 Birr | 243 (29.6) |

| 100–300 Birr | 424 (51.6) |

| >300 Birr | 77 (9.4) |

| Refuse to disclose income | 77 (9.4) |

*merchants, Quran tutors, shop keepers.

The study demonstrated that TB was familiar among pastoralist communities in the study area. The majority (92.8%) of the participants (52.2% males and 47.8% females) had heard about TB (Kahoo in the local language), similar to the results from other Ethiopian studies [10, 11]. The common sources of information mentioned by the respondents were radio (38.6%), health service providers (33.2%), and the rest from friends, schools, and relatives (Table 2). As newspapers and televisions were not commonly used in the study area, most of the Somalis had radio listening habit especially the Somali BBC which could be the main source of health information including TB, similar to the study carried out in Nepal [12].

Table 2.

Distributions of respondents by source of information on TB (n = 821).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Heard of TB | |

| Yes | 762 (92.8) |

| No |

59 (7.20) |

| Source of information | |

| Radio | 294 (38.6) |

| Health service provider | 253 (33.2) |

| Friends/Relatives | 163 (21.4) |

| Schools/Teachers | 52 (6.8) |

Even though TB is familiar in the study area, there is a wide knowledge gap regarding the causes of the disease among the respondents. Only 10.1% knew bacteria as the medical cause of TB, whereas the majority of the respondents (89.9%) did not know about the cause. The perceived TB causes among 89.9% pastoralists varied from animals to cold air, food shortage, smoking, chewing khat leaves (Catha edulis forsk), poverty, hand shaking, sexual intercourse, and even magic (Table 3). Dualeh [13] reported internal injury due to hard work and malnutrition as additional perceived causes of TB. As also documented in other Ethiopian studies, low knowledge regarding medical cause of TB might be due to low education coverage or due to its geographical landscape where many rural and mountainous areas were difficult to access by the health extension workers [11, 14]. Being a pastoralist, and because of the need for child labour, has let the school enrolment rates very low in Somali region having an adult literacy rate for men and women of 15% and 12%, respectively [15]. As limited geographical areas are given to HEWs and accessibility is granted through existing monitoring system, however, due to high mobile nature of the community the accessibility and use of health benefits schemes are always doubtful. Lack of knowledge delays in healthcare seeking behavior, diagnosis and treatment, resulted in further increase transmission rate, morbidity, mortality, and socioeconomic problems. About 11% and 2.5% of the participants, respectively, believe in hand shaking and sexual intercourse as TB transmission mode (Table 3) and about 4% respondents avoid hand shaking to prevent TB (Table 5). The community misconception regarding hand shaking and sexual intercourse as TB transmission mode may favor wrong attitude development in the society for patients.

Table 3.

Knowledge regarding causes, transmission sources, and TB prevention modes (n = 762).

| Indicators of knowledge | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Causes of Tuberculosis | |

| Cold air | 213 (28) |

| Shortage of food | 179 (23.5) |

| Smoking/chewing | 99 (13) |

| Dust | 87 (11.4) |

| Poverty | 79 (10.3) |

| Bacteria/germ | 77 (10.1) |

| Animals | 22 (2.9) |

| Magic | 05 (0.7) |

| Others* | 01 (0.1) |

| Symptom of TB | |

| Weight loss | 261 (34.3) |

| Coughing blood | 154 (20.2) |

| Cough lasting >2 weeks | 88 (11.5) |

| Chest pain | 75 (9.8) |

| Vomiting | 58 (7.6) |

| Weakness | 57 (7.5) |

| Loss of appetite | 35 (4.6) |

| Shortness of breath | 26 (3.4) |

| Fever/sweating | 02 (0.3) |

| Do not know | 06 (0.8) |

| Mode of transmission | |

| By droplet through air | 228 (29.9) |

| Eating utensils | 180 (23.6) |

| Drinking raw milk | 142 (18.6) |

| Hand shaking | 87 (11.4) |

| Sharing towels | 74 (9.7) |

| Sexual intercourse | 19 (2.5) |

| Other** | 10 (1.4) |

| Do not know | 22 (2.9) |

*Sinful act, **drinking raw animal blood and meat.

Table 5.

Respondents' knowledge on transmission and prevention of TB.

| Indicators of knowledge about TB transmission and prevention | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Number (%) | |

| Who can be infected with TB | |

| Anybody | 361 (47.4) |

| Poor people | 149 (19.6) |

| Homeless people | 101 (13.3) |

| Alcoholics | 65 (8.5) |

| Drug users | 29 (3.8) |

| People living with HIV | 19 (2.5) |

| Prisoners | 04 (0.5) |

| Do not know | 34 (4.4) |

| Preventive methods | |

| Covering nose and mouth | 315 (41.3) |

| Through balanced diet | 86 (11.3) |

| BCG vaccination | 160 (21.1) |

| Avoid smoking | 125 (16.1) |

| Avoid drinking alcohol | 23 (3.3) |

| Avoid handshaking | 31 (4.1) |

| Avoid sharing dishes | 08 (1.0) |

| Not sharing bed with others | 13 (1.7) |

| Others* | 01 (0.1) |

*Early treatment, food, and by avoiding sex.

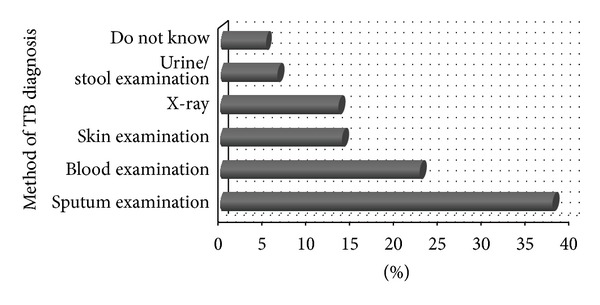

Regarding the best method for TB diagnosis, the present study revealed that 37.9% of the participants reported correct sputum examination while the rest (62.1%) mentioned blood diagnosis, skin and urine and stool examination, and X-ray methods (Figure 1). Most (63.7%) of the study participants in Nepal reported sputum examination as the main TB infection diagnostic method while others mentioned blood and skin examination, physical examination, and X-ray [12].

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of respondents by knowledge on method of TB diagnosis.

The studied pastoralists had good knowledge on TB prevention. About 41.3% expressed nose and mouth covering during sneezing and coughing and 21.0% stated BCG vaccination as preventive methods. Regarding disease treatment, majority of the Shinille pastoralists (98.3%) knew that TB is curable (Table 4) which is in accordance with the study carried out in Afar district, Ethiopia [10]. Majority of the study participants (93.3%) believed that TB treatment is well done with modern medicines. In earlier study from Ethiopia 87.7% informants reported the use of modern drugs as a better option, whereas the rest mentioned both modern drugs and traditional medicines [10].

Table 4.

Percentage distribution of respondents' knowledge regarding TB treatment (n = 762).

| Variable | Frequency | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| TB is treatable | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) |

| Yes | 389 (51.0) | 360 (47.2) | 749 (98.3) |

| No | 09 (1.2) | 04 (0.5) | 13 (1.7) |

| TB treatment better through | |||

| Modern drug | 369 (48.4) | 342 (44.9) | 711 (93.3) |

| Traditional | 03 (0.4) | 05 (0.7) | 08 (1.1) |

| Both | 19 (2.5) | 11 (1.4) | 30 (3.9) |

| Do not know | 07 (0.9) | 06 (0.8) | 13 (1.7) |

In accordance with finding from Gondar city of Ethiopia [16], 47.4% of the study participants reported that anybody can be infected with TB while others reported poor, homeless people, alcoholics, drug users, people living with HIV/AIDS, and prisoners could be infected (Table 5). Majority (93.7%) of the pastoralists believed animals to be the source of TB, and when asked about that, 30.1% responded about sharing same shelter with animals, 25.8% replied about drinking water from the common source and drinking raw milk (18.3%), eating raw meat (13.3%), and drinking raw animal blood (12.5%). Regarding housing conditions and TB, majority (95.3%) of the respondents believed that TB had relation with housing conditions like cooking and sleeping in same room (36.0%), improper ventilation (31.0%), and house cleanliness (33%). Smoking and alcohol consumption have also been cited in other studies conducted in India and Kenya [17, 18]. Respondents' perception of overcrowding of people sleeping in windowless rooms as a risk factor in acquiring infections among the pastoralists in Arusha, Tanzania [19]. In Eastern Ethiopia living in a single room was one of the reported factors that increased the risk of acquiring TB infection [11]. Hence, attention should be given to prevent disease transmission from lack of ventilation since in the study area all family members culturally construct single room house without windows and used it for cooking and sleeping purposes.

The present study showed high proportion of negative attitudes among pastoralist community. The common attitude found was feeling ashamed if relative/family member gets infected with TB (62.2%), keeping it secret if self or family member/relative get TB infection (43.4%), being afraid of TB patients (31.1%), considering the disease as a punishment for sinful act (34.8%), and believing that TB affects breast feeding (46.2%). Almost half of the study participants (49.9%) were not willing to provide care to their relatives suffering with TB, do not allow their children to marry cured TB patient (67.2%), a man/woman once having TB becomes infertile (36%), and around 26.6% of the informants were not willing to perform religious ceremonies with TB patients on treatment. Some respondents in Andhra Pradesh state of India attributed TB disease to sin, wrath of deities, witchcraft, evil eye, fate, and so forth [20]. In a study in Philippines respondents described TB as being shameful and a “bad mark on the family” [21].

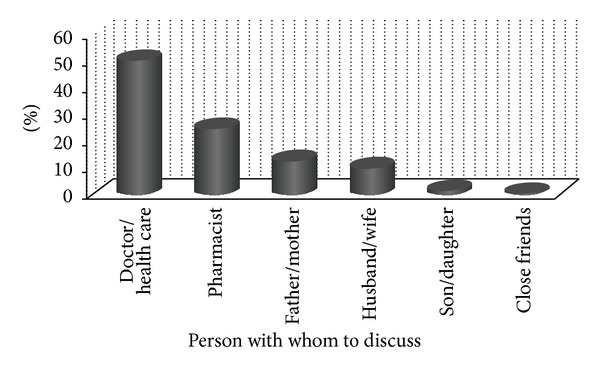

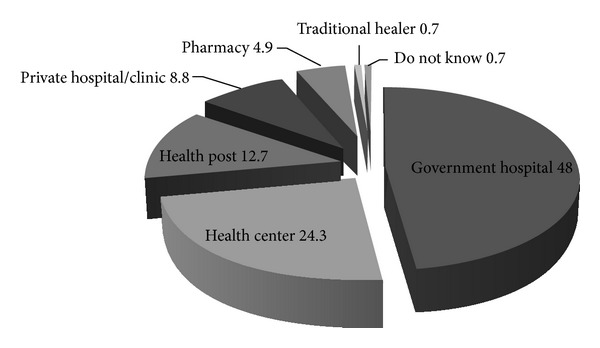

The current study revealed that about half of the study participants (50.3%) discuss their problem with doctors/health care provider, while other discussed with pharmacist, parents, spouse, children, and close friends accordingly (Figure 2). The health seeking behaviour revealed that 48.0% and 24.3% of the respondents, respectively, preferred to visit government hospital and health centre if affected with TB (Figure 3) which might be attributed to the current TB control due strategy of Ethiopia where the FMoH creates awareness about TB through regular advertisement using mass media. The media also advises and encourages TB infected individuals to visit nearby government and private health institution and discuss their problems with health care providers. However, the percentage of TB affected people visiting hospitals is quite low when compared with that of 74.3% reported from Nepal [12].

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of respondents to discuss their problem on TB infection.

Figure 3.

Percentage distribution of respondents preference for TB treatment.

Regarding the pastoralist daily activities to avoid TB, 22.3% of them kept proper room ventilation, 15.0% do not sleep in the same room with animals, 14.6% do not share bed with sick patients, 13.9% do not drink raw milk, 12.2% do not eat raw meat, and do not share utensils with sick patients (11.0%) (Table 5). The present study found that about 99.5% of the respondents practised hand washing especially after collecting dung and touching the sick animals which is an encouraging fact which must be sustained among the society.

The current study revealed that, out of all sociodemographic variables tested, occupation, family size, and household income/month had significance association and become a predictive of overall high TB knowledge. Results from multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 6) showed that agro-pastoralist, as an occupation, is less likely to be predictive of overall knowledge of TB at (AOR: 1.21, 95% CI: (0.73–2.02)) than pastoralists, which is consistent with the finding of a previous study from Eastern Ethiopia [7] and in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Tanzania [19]. This might be because nomadic pastoralists have least access to health and other social services [22, 23]. This study reported that the participants whose household income >300 Birr/month (AOR: 2.03, 95% CI: (1.06–3.86)) were associated with having high knowledge on TB compared to those who had income <300 Birr/month; this might be explained as income increased the chance of getting access to information, education and seeking health care also increased. This study also found that pastoralists having family size of <five become a predictive of high overall knowledge of TB than those having family size >five at (AOR: 0.05, 95% CI: (0.04–0.08)).

Table 6.

Crude and adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of determinants of TB knowledge.

| Predictors | Knowledgeable on TB | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 157 | 207 | 1 | 1 |

| Female* | 191 | 207 | 0.82 (0.62−1.04) | 0.69 (0.47−1.02) |

| Age (Years) | ||||

| 18–24* | 97 | 94 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–34 | 117 | 119 | 0.14 (0.17−1.15) | 5.31 (0.33−86.13) |

| 35–44 | 83 | 111 | 0.14 (0.18−1.20) | 0.32 (0.09−1.13) |

| 45–54 | 43 | 72 | 0.19 (0.23−1.58) | 0.36 (0.11−1.26) |

| 55+ | 7 | 11 | 0.24 (0.03−2.01) | 0.50 (0.14−1.74) |

| Do not know | 1 | 7 | 0.02 (0.02−2.23) | 0.77 (0.21−2.80) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married* | 274 | 342 | 1 | 1 |

| Unmarried | 53 | 50 | 0.76 (0.49−1.15) | 0.57 (0.17−1.94) |

| Separated | 7 | 4 | 0.46 (0.13−1.58) | 0.69 (0.19−2.51) |

| Divorced | 9 | 6 | 0.53 (0.19−1.52) | 0.29 (0.04−2.18) |

| Widowed | 5 | 12 | 1.92 (0.66−5.52) | 0.60 (0.09−3.93) |

| Occupation | ||||

| Pastoralist* | 142 | 197 | 1 | 1 |

| Agro pastoralist | 62 | 93 | 1.08 (0.73−1.59) | 1.21 (0.73−2.02) |

| Cattle keeping and farming | 135 | 119 | 0.63 (0.46−0.88) | 0.45 (0.29−0.69) |

| Others | 9 | 5 | 0.40 (0.13−1.22) | 0.21 (0.05−1.77) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Somali | 324 | 397 | 1 | 1 |

| Oromo* | 24 | 17 | 0.57 (0.30−1.09) | 2.24 (0.99−5.07) |

| Household income | ||||

| Less than 100 Birr* | 103 | 122 | 1 | 1 |

| 100–300 Birr | 178 | 220 | 1.69 (0.98−2.93) | 1.86 (0.93−3.72) |

| >300 Birr | 27 | 44 | 1.76 (1.05−2.97) | 2.03 (1.06−3.86) |

| Refuse to answer | 40 | 28 | 2.33 (1.18−4.59) | 3.04 (1.29−7.18) |

| Family size | ||||

| ≤five* | 112 | 370 | 1 | 1 |

| >five | 236 | 44 | 0.05 (0.04−0.08) | 0.05 (0.03−0.07) |

Knowledge score 5.4 (maximum of 8 score) was used as a cut off for comparison.

Variables significantly related (P < .05) to knowledge score on univariate analysis were included for multivariate logistic regression analysis. *Reference category.

4. Conclusion

This study documented familiarity towards TB but observed gaps and low overall knowledge about the disease in the studied pastoral community. Negative attitudes especially discrimination with infected individuals were also revealed. The study participants' practices or activities in avoiding TB and their health seeking behaviour were interesting and should be appreciated by the regional health bureau as it is one of the control strategies for TB. It is vital, therefore, for the regional health bureau to find ways of improving pastoralist's knowledge gap on TB and design strategies to create positive attitude to avoid discrimination of infected individuals with the disease among pastoralist. The regional health bureau should strengthen the available mobile health workers and promote an extensive health education programme to raise the awareness specifically about TB symptoms, means of transmission, prevention, and treatment in relation to the community misconceptions. Training should also be provided to members of pastoralist communities including traditional healers regarding TB control programs. Further research is suggested among pastoralists and control groups and different livelihoods systems in the study area.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

The support from Somali Regional Health Bureau, Shinille district, and wards officials are acknowledged gratefully. The authors are thankful to all study participants for their precious time.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control: WHO Report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) Ethiopia. Guidelines for Prevention of Transmission of Tuberculosis in Health Care Facilities, Congregate and Community Setting. Ist edition. Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) Ethiopia; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Somali Regional Health Bureau Report. Personnel communication and data taken from unpublished report. 2009.

- 4.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control, Epidemiology Strategy Financing. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Government of India. TB India 2011, RNTCP Status Report. New Delhi, India: Central TB Division New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephen D. Vulnerable Livelihoods in Somali Region. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gele AA, Bjune G, Abebe F. Pastoralism and delay in diagnosis of TB in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2009;9, article 5 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Central Statistical Agency. Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Results for Somali Region. Vol. 1. Central Statistical Agency; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniel WW. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Science. 8th edition. Willey International; 2005. (pp. 658–659). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mengistu L, Gobena A, Gezahegne M, et al. Knowledge and perception of pulmonary tuberculosis in pastoral communities in the middle and lower awash valley of afar region, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2010;10, article 187 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mesfin MM, Tasew TW, Tareke IG, Mulugeta GWM, Richard MJ. Community knowledge, attitudes and practices on pulmonary tuberculosis and their choice of treatment supervisor in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2005;19:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Government of Nepal. Report of Mahottari District. Ministry of Health and Population and National Tuberculosis Centre; 2009. Knowledge, attitude and practices: Study on tuberculosis among community people. http://library.elibrary-mohp.gov.np/mohp/collect/mohpcoll/archives/mohp:199/4.dir/doc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dualeh MW. Health situation of the drought-affected populations in the Somali National Regional State. 2000, http://www.who.int/disasters/repo/5856.doc.

- 14.Austrian Development Cooperation. Ethiopia Subprogram Health 2004–2006. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry for Foreign Affairs; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Central Statistical Agency. Census 2007. 2008, http://www.etharc.org/resources/download/viewcategory/68.

- 16.Tessema B, Muche A, Bekele A, Reissig D, Emmrich F, Sack U. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at Gondar University Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a five-year retrospective study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9, article 371 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair DM, George A, Chacko KT. Tuberculosis in Bombay: new insights from poor urban patients. Health Policy and Planning. 1997;12(1):77–85. doi: 10.1093/heapol/12.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liefooghe R, Baliddawa JB. From their own perspective. A Kenyan community’s perception of tuberculosis. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1997;2(8):809–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mfinanga S, Mørkve O, Kazwala RR, et al. Tribal differences in perception of tuberculosis: a possible role in tuberculosis control in Arusha, Tanzania. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2003;7(10):933–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venkatraju B, Prasad S. Beliefs of patients about the causes of Tuberculosis in rural Andhra Pradesh. International Journal of Nursing and Midwifery. 2010;2(2):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichter M. Illness semantics and international health: the weak lungs/TB complex in the Philippines. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38(5):649–663. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheik-Mohamed A, Velema JP. Where health care has no access: the nomadic populations of sub-Saharan Africa. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1999;4(10):695–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United Nations Development Programme. Between a rock and hard place: armed violence in African pastoral communities. UNDP Report. 2007 http://www.genevadeclaration.org/fileadmin/docs/regional-publications/Armed-Violence-in-African-Pastoral-Communities.pdf.