Abstract

Background and Objectives

Strains of Helicobacter cetorum have been cultured from several marine mammals and have been found to be closely related in 16 S rDNA sequence to the human gastric pathogen H. pylori, but their genomes were not characterized further.

Methods

The genomes of H. cetorum strains from a dolphin and a whale were sequenced completely using 454 technology and PCR and capillary sequencing.

Results

These genomes are 1.8 and 1.95 mb in size, some 7–26% larger than H. pylori genomes, and differ markedly from one another in gene content, and sequences and arrangements of shared genes. However, each strain is more related overall to H. pylori and its descendant H. acinonychis than to other known species. These H. cetorum strains lack cag pathogenicity islands, but contain novel alleles of the virulence-associated vacuolating cytotoxin (vacA) gene. Of particular note are (i) an extra triplet of vacA genes with ≤50% protein-level identity to each other in the 5′ two-thirds of the gene needed for host factor interaction; (ii) divergent sets of outer membrane protein genes; (iii) several metabolic genes distinct from those of H. pylori; (iv) genes for an iron-cofactored urease related to those of Helicobacter species from terrestrial carnivores, in addition to genes for a nickel co-factored urease; and (v) members of the slr multigene family, some of which modulate host responses to infection and improve Helicobacter growth with mammalian cells.

Conclusions

Our genome sequence data provide a glimpse into the novelty and great genetic diversity of marine helicobacters. These data should aid further analyses of microbial genome diversity and evolution and infection and disease mechanisms in vast and often fragile ocean ecosystems.

Introduction

The genus Helicobacter consists of Gram-negative bacterial species that live in the gastrointestinal tracts of diverse animal hosts [1]–[3]. H. pylori, the best known of these species, chronically infects the gastric (stomach) mucosa of billions of people worldwide, is a major cause of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer, and is very diverse genetically. It is transmitted preferentially within families and local communities, apparently without major environmental reservoirs or alternate hosts [4]–[7].

Much less is understood about transmission and infection mechanisms, virulence, and population biology and evolution of other Helicobacter species. Although most of these species are known from land animals, a few also have been discovered in marine mammals. Of particular note is H. cetorum from marine mammals, defined to date primarily by its 16 S rDNA sequences [8]–[13], which are more closely related to those of H. pylori and the big cat pathogen H. acinonychis [14] than to those of other known species. PCR and 16 S rDNA sequence data indicate that H. cetorum is present in oceans worldwide [8]–[13], and suggest that it or close relatives also caused gastric infections in some urban Venezuelans [15] and lymph node infections in mule deer in Montana [16]. Interestingly, the genus Helicobacter belongs to the Epsilonproteobacteria, some of whose other members are associated variously with coral and sponge disease, and gastropods and biofilms of deep-sea hydrothermal vents [17]–[21]. Here, we sequenced the genomes of H. cetorum strains from a whale and a dolphin to help define this species' gene content and diversity, with long-range goals of better understanding pathogen transmission and infection mechanisms in marine ecosystems, genome evolution, and possible impacts of non-pylori Helicobacter species on animal and human health.

Methods

H. cetorum Culture and Genome Sequencing

The two H. cetorum strains that we sequenced had been cultured by Harper et al [8] from the main (glandular) stomach of a beached Atlantic white sided dolphin (MIT 99–5656, here called “dolphin strain”), and the feces of a captive (Mystic Aquarium) Beluga whale with esophageal and stomach ulcers (MIT 00-7128, here called “whale strain”), and had been deposited as ATCC BAA-540 and ATCC BAA-429 (or CCUG 52418 T), respectively [8]. The whale strain, although cultured from feces, was inferred to have lived in its host's stomach because its 16 S rDNA sequence was identical to that obtained by PCR from the animal's gastric tissue [8]. We grew these strains from single colonies using standard H. pylori culture conditions (BHI blood agar plates at 37°C, in 5% CO2, 10% O2 and 85% N2) and extracted genomic DNA as described [22], [23]. Genomic DNAs were sequenced using 454 FLX Titanium paired-end shotgun sequencing (>40-fold coverage), and reads were assembled using 454 Corporation Newbler software (164 and 88 contigs, dolphin and whale strains, respectively) by MOGene Corporation (St Louis, MO). We determined relative positions of contigs by PCR and filled all gaps between contigs by capillary sequencing of PCR products. The genome sequences were deposited in GenBank as accessions CP003481.1 (chromosome) and CP003482.1 (plasmid) of the dolphin strain, and NC_017737.1 (chromosome) and NC_017738.1 (plasmid) of the whale strain, and were annotated by the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Automatic Annotation Pipeline staff, as described [23].

Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetic Analysis

Complete, fully-annotated chromosome and plasmid sequences of the Helicobacter strains and species listed in Table 1 were downloaded from the NCBI ftp server; a database containing all predicted protein sequences was assembled and low-quality protein sequences were removed automatically. Reciprocal all-versus-all BLASTP was performed and results were processed by OrthoMCL using default parameters [24]. The OrthoMCL output was filtered using a perl script to produce different lists of ortholog groups (e.g. ortholog groups present in H. cetorum but not in H. pylori). Using the OrthoMCL output, we selected 126 genes in the core genome of gastric Helicobacter species with orthologs in a non-gastric outgroup species, H. hepaticus (Table S1). Alignments for each of these one-to-one rooted core genes were generated at the amino acid level using MAFFT-FFT-NS-i v.7 [25]; the proteins were back-translated to nucleotide sequence using Translatorx perl script [26]; aligned DNA sequences were concatenated using a perl script, and the phylogenetic tree was inferred using PhyML [27] by applying the following parameters: -b 2, -m GTR, -o tlr –a e, -c 6. A distance matrix of the concatenated aligned core genes was calculated using DISTMAT implemented in jEMBOSS using Kimura-2 [28].

Table 1. Strains and species used in this study.

The two H. cetorum genome sequences were submitted to GGDC 2.0 [29], available at http://ggdc.dsmz.de, to calculate whole-genome distance and infer the degree of DNA-DNA hybridization between them.

To identify orthologs common to the two H. cetorum strains, the complete set of predicted proteins of one strain was compared with that of the other by reciprocal BLASTP. A BLAST score ratio cut-off of 0.4 was used to define two proteins as homologs.

Proteins identified by OrthoMCL as belonging to groups of orthologs that occur only in H. cetorum strains were then used as queries for BLASTP homology searches against the total NCBI database available in August 2013 to find related sequences, especially in H. pylori, and to better understand patterns of sequence conservation and divergence among related proteins.

Results

Phylogenetic Relationships of H. cetorum Strains

The chromosomes of the H. cetorum whale and dolphin and strains are 1.95 and 1.83 Mb Mb in size, respectively — a few hundred kb larger than is typical of H. pylori (1.55–1.71 Mb). Each strain also contains a plasmid, 12.5 and 14.1 kb in size, respectively (Table 2). The complete 16 S and 23 S rDNA sequences of these two strains differ by only 5 bp and 10 bp, respectively, and each is more closely related to the rDNAs of H. pylori and H. acinonychis than to those of other known species [8 and present results]. Whole genome BLASTN (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) analyses confirmed and extended inferences from rDNA data — showing that these two strains are more closely related to various H. pylori strains or H. acinonychis than to any other known bacterial species. That said, only ∼64% of whale and ∼74% of dolphin strain genomes are found by BLASTN criteria in H. pylori genomes, and reciprocally, only ∼75–80% of representative H. pylori strain genome sequences are found in these H. cetorum genomes.

Table 2. General features of H. cetorum genomes.

| Feature | MIT 00–7128, whale strain | MIT 99–5656, dolphin strain |

| Chromosome | ||

| Size bp | 1 947 646 | 1 833 666 |

| G+C content (%) | 34,5 | 35,8 |

| % Coding | 88 | 88,4 |

| Number genes | 1 775 | 1 731 |

| Protein coding | 1 731 | 1 689 |

| Structural rRNAs | 38 | 36 |

| 16 S,23 S,5 S rRNAs | 2,2,2 | 2,2,2 |

| vacA | one next to cysS | one next to cysS, plus three divergent between ruvA, ruvB |

| cag pathogenicity island | Absent | absent |

| Urease | two: nickel & iron co-factored | two: nickel & iron co-factored |

| mobile DNAs | two TnPZ transposons; one near complete prophage with numerous rearrangements and insertions of probably non-phage DNAs | one IS605- and twenty IS606-like insertion sequences; one fragmented TnPZ transposon; multiple and duplicated prophage fragments |

| Plasmid | one, pHCW | one, pHCD |

| size (bp) | 12 465 | 14 124 |

| G+C content (%) | 34,5 | 32,7 |

| Number genes (orfs) | 13 | 15 |

| Other features | putative replication and transfer genes also present in dolphin strain plasmid | putative replication and transfer genes also present in whale strain plasmid; two IS606, nearly identical to chromosomal IS606 |

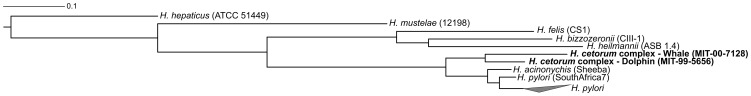

The phylogenetic positions of these strains (Figure 1) were also inferred by Maximum Likelihood using 126 concatenated core genes (Table S1). All nodes in this tree are well supported with Chi2-based parameter branch values of over 99%. The two strains clustered together in the sister clade of H. pylori/H. acinonychis, but are separated by relatively long branches. The kimura-2 corrected distance value between these two strains, calculated based on these 126 core genes, is 16.15 substitutions per 100 bp (16%). Using these same core genes, the average distance between H. pylori or H. acinonychis and H. cetorum is approximately 20%, whereas that among sequenced H. pylori genomes is only 4.1%. Thus, at 16% substitution, these two H. cetorum strains differ from each other far more than would have been expected based on the near identity of their 16 S rRNAs (1489/1494 bp).

Figure 1. Phylogram representing maximum-likelihood tree of gastric Helicobacter species based on 126 aligned and concatenated core genes.

The tree was inferred using PhyML applying General Time Reversible (GTR) model, estimating the gamma shape parameter by setting the number of substitution rate categories at 6. Statistical tests for branch support were conducted via a Chi2-based parametric approximate likelihood-ratio test (aLRT). All nodes are supported with aLRT values > 99%. The topology, branch lengths and rate parameters of the starting tree were optimized. The enteric (non-gastric) species H. hepaticus was used as outgroup. The core genes used for this figure are listed in Table S1.

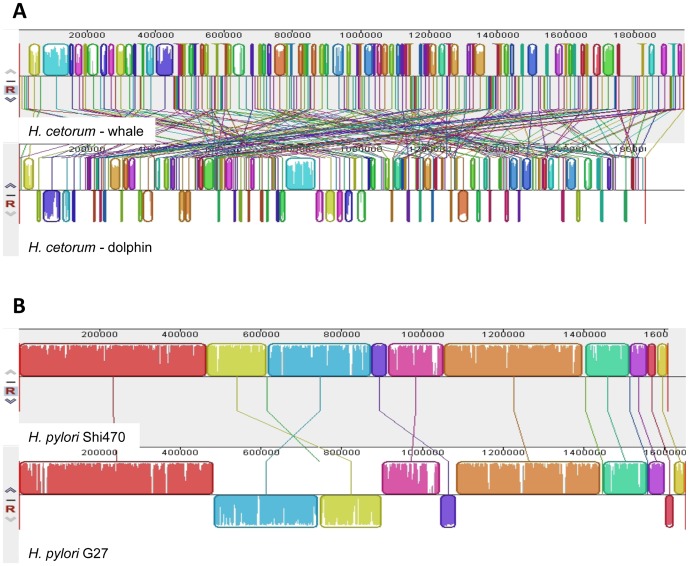

Four additional tests were used to further characterize relationships of the H. cetorum strains to each other and to H. pylori, genome-wide. First, Mega BLAST analysis indicated that only 66% of dolphin strain DNA sequences are present in the larger whale strain genome. Similarly, BLASTN analysis of 1 kb chromosomal segments taken sequentially from the dolphin strain without regard to gene content indicated that some 30% of them have no significant homology to whale strain sequences. In contrast, pairs of H. pylori strains typically share >90% of chromosomal DNA sequences. The H. cetorum strain-specific DNAs are widely dispersed about their genomes, not concentrated in just one or a few sites (e.g., as chromosomal islands). Second, only 11% of sequential 1 kb chromosomal segments from the dolphin strain were at least 95% identical to whale strain sequences for at least 500 bp. In contrast, with even the least related pairs of H. pylori strains, ≥95% identities for >500 bp are found in more than 40% of such 1 kb segments. Third, chromosome alignment using MAUVE software revealed 204 differences in location and orientation of shared DNA segments between the H. cetorum strains (Figure 2A). In addition, the dolphin and whale strain chromosomes exhibited 135 and 203 differences, respectively, in DNA arrangement when aligned with that of a representative H. pylori strain (G27 [30]), whereas less than 10–15 DNA arrangement differences are found when comparing chromosomes of most other H. pylori strains with one another, as illustrated with strains G27 and Shi470 in Figure 2B [see also reference 23]. Fourth, DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) parameters, estimated in silico by calculating whole-genome distance using the GGDC website, yielded a DDH estimate 29.1%±2.44 for these two strains. Based on conventional criteria [29], this indicates a probability via logistic regression of only 0.07% that they belong to the same species. A fifth test of relatedness and divergence emerged from our in silico proteome analyses, below.

Figure 2. MAUVE alignment of representative Helicobacter chromosomes.

For MAUVE software see http://gel.ahabs.wisc.edu/mauve/. A. Two H. cetorum genomes. B. Two representative H. pylori genomes. For further illustration of the higher conservation of gene order and orientation in H. pylori relative to H. cetorum, see [23].

In silico Proteome Analysis

Examination of annotated genomes identified 86,309 predicted protein sequences in the chromosomes of 48 H. pylori strains and seven other Helicobacter species and in 25 Helicobacter plasmids (Table 1). Based on MCL clustering, 96% of the proteins were divided into 2,934 groups of orthologs (GOs), of which 1,478 and 1,434 GOs were detected in the whale and dolphin strain proteomes, respectively. Approximately 10% (164) of whale and 7% (112) of dolphin strain proteins have no orthologs in other genome sequenced Helicobacter species, and thus might be unique to H. cetorum. Among the 2,934 GOs, 157 are represented in whale but not dolphin strain proteomes, and 113 are represented in dolphin but not whale strain proteomes. The two H. cetorum strain proteomes were compared further using a BLAST score ratio cut-off of 0.4, which is more stringent than OrthoMCL, and can separate distant proteins that cluster in the same group by MCL. BLAST analysis identified 411 whale strain proteins (24% of proteome), with no significant homology to any dolphin strain protein, and conversely, 346 dolphin strain proteins (22% of proteome) with no significant homology to any whale strain protein. Thus, these data indicate considerable differences in the proteomes of these two H. cetorum strains.

H. cetorum-specific Genes

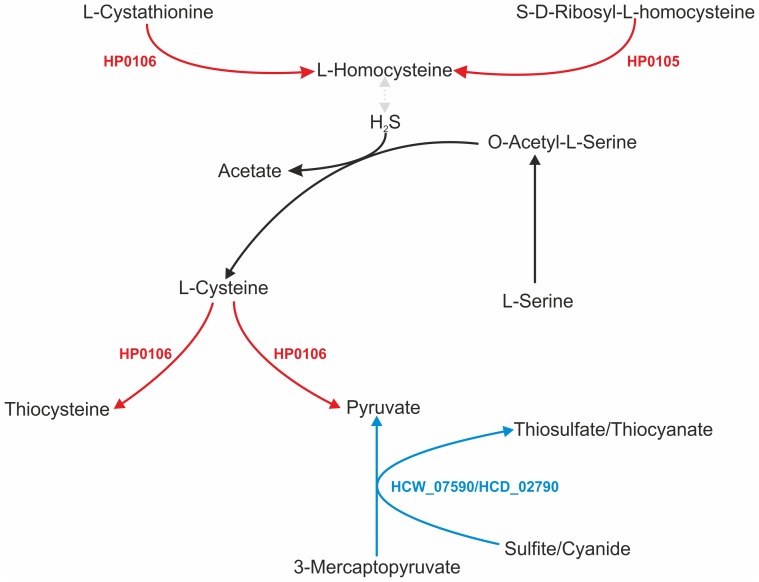

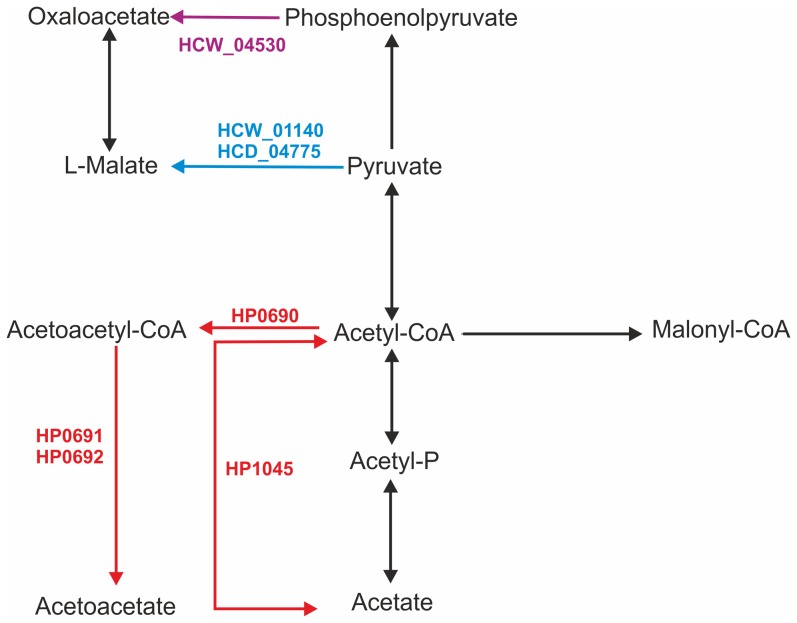

Forty-six GOs were found in the two H. cetorum strains but not in any H. pylori strain (Tables 3 and 4) by initial OrthoMCL-based screening using the genome-sequenced strains listed in Table 1. Of particular interest are enzymes of central intermediary metabolism such as a rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase (HCW_07590, HCD_02790), which KEGG pathway analysis suggests could catalyze synthesis of pyruvate and thiosulfate from 3-mercaptopyruvate (Figure 3; blue arrows) or possibly other substrates. Homologous sulfurtransferases seem to be absent from nearly all other genome-sequenced Epsilonproteobacteria, including all other Helicobacter spp. and Campylobacter spp. A second example is that of the NADP-dependent malic enzyme (HCW_01140, HCD_04775), that could catalyze synthesis of L-malate from pyruvate (Figure 4, blue arrows). Related malic enzymes have been found in many extragastric Helicobacter spp. and in Campylobacter spp., but not in any H. pylori strain. Conversely, 22 GOs were detected in the H. pylori/H. acinonychis clade but not in H. cetorum, as illustrated in Table 5. We note, in particular, enzymes that could mediate synthesis of L-homocysteine, conversion of L-cysteine to thiocysteine or pyruvate (Figures 3, red arrows); and syntheses of acetoacetyl-CoA and acetate from acetyl-CoA, and of acetoacetate from acetoacetyl-CoA (Figure 4, red arrows). Finally, a phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase that could catalyze oxaloacetate synthesis from phosphoenolpyruvate (Figure 4; light green arrow) is encoded in the genomes of the whale strain and of several other Helicobacter species, but not in the dolphin strain genome, nor in any H. pylori or Campylobacter strain genome sequenced to date.

Table 3. H. cetorum whale strain proteins distinct from those in H. pylori strains.

| Locus Tag | GO | # amino acids (aa) | Annotation | Matches in H. cetorum, aa identity (blastp) | Matches in H. pylori aa identity (blastp) |

| HCW_00105 | HEL3581 | 246 | Hypothetical | HCD_03325, 54% in aa 68–139 | None |

| HCW_00115 | HEL3059 | 122 | Hypothetical | HCD_03315, 89% | None |

| HCW_00125 | HEL3852 | 246 | HcpA | HCD_03275, 95% | Most strains, ≤32% in aa ∼97–241, |

| HCW_00130 | HEL3853 | 421 | Hypothetical | HCD_03280, 94% | None |

| HCW_00595 | HEL3854 | 208 | hypothetical, COG0500, SAM-dependent methyltransferase | HCD_03930, 98% | None |

| HCW_01140 | HEL3270 | 420 | Malate dehydrogenase | HCD_04775, 95% | None (1) |

| HCW_01270 | HEL3858 | 290 | COG0338, DNA adenine methylase | HCD_08595 | Two strains, 65%, 72% (2) |

| HCW_01595 | HEL3859 | 1437 | COG3468 anticodon nuclease masking agent; | None | None (3) |

| HCW_01740 | HEL3860 | 390 | COG0477, drug transport transmembrane | HCD_00760, 98% | None |

| HCW_02225 | HEL3057 | 752 | OMP; pfam01856 | HCD_02935, 54%; HCD_05585, 50%; HCW_07955, 32%; HCD_00325, 33%; HCD_08430, 31%; HCD_05575, 30% (4) | Many strains, ≤28% |

| HCW_02500 | HEL3861 | 488 aa | Hypothetical | HCD_03555, 38% in aa 1–281, 61% in aa 285–488 | None |

| HCW_03170 | HEL3864 | 891 | OMP, HomB, pfam01856 | HCD_05580, 66% | Many strains, ≤31% |

| HCW_03370 | HEL3867 | 73 | copper binding, chaperone | HCD_06365, 60% | Many strains, ≤42% (5) |

| HCW_03525 | HEL3071 | 211 | Hypothetical | HCD_07120, 50%; HCD_07510, 51%; HCD_00640, 42%; HCD_01920,42% | Two strains, ≤46% |

| HCW_04205 | HEL3869 | 341 | Hypothetical | HCD_08400, 92%; HCD_02210, 75% in aa 182–301 | None |

| HCW_04215 | HEL3870 | 146 | Hypothetical | HCD_08395, 97% | None |

| HCW_04220 | HEL3871 | 155 | Hypothetical | HCD_08385, 74%; HCW_05395, 89% in aa 1–64 | Several strains, ≤79% in aa 1–62 |

| HCW_04245 | HEL3872 | 74 | Hypothetical | HCD_08370, 93% | None |

| HCW_04250 | HEL3873 | 113 | Hypothetical | HCD_08365, 95% | None |

| HCW_04255 | HEL3874 | 332 | COG0582 integrase (6) | HCD_08360, 92% | Many strains, ≤39% |

| HCW_04280 | HEL3061 | 291 | Hypothetical | HCD_07575, 51% in aa 1–167 | None |

| HCW_04310 | HEL3062 | 72 | Hypothetical | HCD_07600, 88% | None |

| HCW_04320 | HEL3625 | 603 | Hypothetical | HCD_07610, 79% in aa 1–100, 80% in aa 336–603 | Many strains, ≤28% in N terminal, C sub-terminal domains |

| HCW_04375 | HEL3875 | 69 | Hypothetical | HCD_07645, 94% | None |

| HCW_04395 | HEL3876 | 191 | Hypothetical | HCD_07665, 83% | None |

| HCW_04410 | HEL3877 | 111 | Hypothetical | HCD_07680, 80% | Many strains, ≤27% |

| HCW_04415 | HEL3878 | 237 | Hypothetical | HCD_07685, 96% | Many strains, ≤29% |

| HCW_04530 | HEL2846 | 870 | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | None | None (7) |

| HCW_04560 | HEL3620 | 385 | COG0286 type I restriction-modification HsdM | HCD_02110, 93% | Many strains, ≥38% in aa 65–383 |

| HCW_04565 | HEL3879 | 194 | COG0732 type I restriction-modification HsdS | HCD_02105, 97% | None |

| HCW_04635 | HEL3880 | 470 | OMP_2, pfam02521 | HCD_05480, 78%; HCW_06475, 40% | Many strains, ≤38% |

| HCW_04920 | HEL2809 | 799 | OMP, HopG, pfam01856 | HCD_06965, 65% in aa 64–799; HCD_06965, 65%; HCW_06795, 99%; HCW_07665, 76%; HCW_06910, 52%; HCW_07970, in 482–799, 79% (4) | Many strains, ≤40% in aa 627–799 |

| HCW_05300 | HEL2800 | 446 | OMP, pfam01856 | HCD_06515, 51%; HCD_02735, 45%; HCD_00320, 44% (4) | None |

| HCW_06445 | HEL3881 | 720 | Type I restriction-modification HsdM | HCD_02745, 72% | None |

| HCW_06450 | HEL3882 | 481 | SSF116734, Type I restriction-modification HsdS | HCD_02740, 40% | None |

| HCW_06795 | HEL2809 | 799 | OMP, HopG, pfam01856 | HCD_06965, 65% in aa 64–799; HCD_06965, 65%; HCW_04920, 99%; HCW_07665, 76%; HCW_06910, 52%; HCW_07970, in 482–799, 79% (4) | None |

| HCW_06910 | HEL2809 | 718 | OMP, HopG, pfam01856 | HCW _04920 & _06795, 52%; HCD_06965, 52%; HCW_07970, 74% in aa 509–718 (4) | None |

| HCW_07065 | HEL3884 | 419 | OMP3 | HCD_07105, 45%; HCD_08025, 61%; HCW_07110, 52% in aa 154–419; HCW_07075, 52% in aa 152–419 | Many strains, ≤48% in aa 161–419 |

| HCW_07120 | HEL3885 | 128 | hypothetical; CRISPR/Cas system associated | HCD_08225, 83%in aa 69–128 | None |

| HCW_07125 | HEL3886 | 274 | CRISPR/Cas system-associated RAMP superfamily protein Cas6 | HCD_08220, 91% in aa 1–192 | None |

| HCW_07130 | HEL3887 | 550 | CRISPR/Cas system-associated protein Cas10 | HCD_08210, 46% in aa 16–132; HCD_08205, 54% in aa 350–421 | None |

| HCW_07495 | HEL3889 | 1054 | COG1002 type II restriction-modification. N-6 adenine methylase | HCD_01155, 90% | One strain, 77% |

| HCW_07510 | HEL7510 | 210 | Hypothetical | HCD_00640, 50%; HCD_07210, 43%; HCD_02790, 64%; HCW_03525, 51%; HCW_01920, 50% | Two strains, ≤53% |

| HCW_07590 | HEL3071 | 413 | COG2897 rhodanese-related sulfur transferase | HCD_02790, 64%; | None (8) |

| HCW_07625 | HEL3891 | 180 | Hypothetical | HCD_0820, 67%; HCD_08215, 25% | |

| HCW_07630 | HEL3073 | 97 | hypothetical; COG0790 FOG: Sel1-like repeat family | HCD_08525, 69%; HCW_07635, 75% | One strain; 50% in aa 59–88 |

| HCW_07635 | HEL3073 | 89 | hypothetical; COG0790 FOG: Sel1-like repeat family | HCD_08525, 74%; HCW_07630, 75% | None |

| HCW_07665 | HEL2809 | 810 | OMP, HopG, pfam01856 | HCD_06965, 66%; HCW_04920 & HCW_06795, 76%; HCW_06910, 52% in aa 97–810; HCW_07970, 43%(4) | Many strains; <38% in C terminal 120 aa |

| HCW_07955 | HEL3892 | 731 | OMP HomB | HCD_00325, 53%; HCD_02935, 33%; HCD_05585, 31%; HCD_03000, 30% in aa 13–503, 79% in aa 550–731; HCD_01075, 34% in aa 177–831; HCD_01075, 34% in aa 208–731; HCW_08600, 37%; HCW_02225, 32% | Many strains, ≤32% ident in aa 177–831 |

| HCW_08150 | HEL3894 | 117 | Hypothetical | HCD_07625, 86% | None |

| HCW_08195 | HEL3895 | 108 | Hypothetical | HCD_08390, 83%; HCW_04200, 83% | None |

| HCW_08600 | HEL3058 | 795 | OMP; pfam01856 | HCD_08430, 54%; HCD_03000, 54%; HCD_00325, 42%; HCD_05585, 32%; HCD_02935 in aa 184–795; HCD_01285, 30%; HCW_02225, 32% in aa 195–795 | Many strains, ≤32% in aa 210–795 |

Campylobacter species.(1) Homologs of HCW_01140 in many

% aa identity in many other H. pylori strains.(2) Distant homologs of HCW_01270 with up to 29

Helicobacter species such as H. bilis, H. winghamensis, and H. fennelliae.(3) Distant homologs of HCW_01595 in other

% and 50% identity overall to HCD_02935 and HCD_05585, but >85% identity to these proteins starting at aa position ∼590 of the 752 aa long protein.(4) For most OMPs in this table, distribution of identities throughout protein is distinctly non-random, with highest sequence conservation in carboxy terminal, and in some cases also amino terminal domains. For example, HCW_02225 exhibits 54

% aa identity in other Helicobacter species including H. cinaedi, H. bizzozeronii, and H. hepaticus.(5) Homologs of HCW_03370 with up to 39

(6) HCW_04255 is just one of four "integrases" annotated in the whale strain proteome.

–54% in H. bizzozeronii, H. felis, H. bilis, H. fennelliae, H. mustelae, H. hepaticus and Wolinella.(7) Homologs of HCW_04530 with identities of 47

–38% in multiple strains of Leptotrichia, Actinobacillus, Providencia, Haemophilus, Morganella, etc.(8) Homologs of HCW_07590 with aa identities of 35

Table 4. H. cetorum dolphin strain proteins distinct from those in H. pylori strains.

| Locus Tag | GO | # amino acids (aa) | protein annotation | Matches in H. cetorum, aa identity (blastp) | Matches in H. pylori, aa identity (blastp) |

| HCD_00320 | HEL2800 | 487 | OMP, HopK, pfam01856 | HCW_05300, 50% in aa 182–487; HCD_08540, 37% in aa 23–367; HCD_02735, 55%; HCD_06515, 51%; | Many strains, ≤37% in aa 330–465 |

| HCD_00325 | HEL3892 | 741 | hypothetical | HCD_03000 & _08430, 47%; HCD_05585, 31%; HCW_07955, 53%; HCW_08600, 42% | Many strains, ≤31% |

| HCD_00760 | HEL3860 | 396 | COG0477, sugar/drug transport membrane | HCW_01740, 98%; | None |

| HCD_01155 | HEL3889 | 1054 | Type II restriction-modification, N-6 adenine methylase | HCW_07495, 90% | One strain, 78% |

| HCD_02105 | HEL3879 | 194 | COG0732 Type I restriction-modification. HsdS | HCW_04565, 97%; | Many strains, ≤25% |

| HCD_02110 | HEL3620 | 385 | COG0286 Type I restriction-modification. HsdM | HCW_04560, 93% | Many strains, ≤37% |

| HCD_02735 | HEL2800 | 506 | OMP, HopK | HCD_08540, 100% in aa 58–336; HCD_06515, 58%; HCD_00320, 55% | Many strains, ≤37% in aa 306–506 |

| HCD_02740 | HEL3882 | 498 | SSF116734: Type I restriction modification. DNA specificity domain superfamily HsdS | HCD_06450, 40% | Many strains, ≤30% ident for <∼200 aa from many parts of protein |

| HCD_02745 | HEL3881 | 720 | COG0286 Type I restriction-modification. N-6 adening methylase HsdM | HCD_06445, 72% | Many strains, ≤24% identity, C terminal ∼half of protein |

| HCD_02790 | HEL3890 | 403 | COG2897 rhodanese-related sulfur transferase | HCW_07590, 64% | None (1) |

| HCD_02935 | HEL3057 | 746 | OMP, pfam01856 | HCW_02225, 55%; HCW_07955, 34%; HCW_08600, 34% in aa 135–746; HCW_03765, 29% in aa 197–746; HCW_02225, 55%; HCD_05585, 55%; HCD_00325, 34%; HCD_05575, 32% | Many strains, ≤28% |

| HCD_03000 | HEL3058 | 806 | OMP, HomB, pfam01856 | HCW_08600, 54%;HCW_07955, 39%; HCD_08430, 78%; HCD_00325, 46%; HCD_05585, 31%; HCD_01285, 30% | Many strains, ≤31% in aa 213–806 |

| HCD_03265 | HEL3059 | 122 | hypothetical | HCW_00115, 89%; HCD_03315, 100%. | None (2) |

| HCD_03275 | HEL3852 | 248 | HcpA, cysteine rich protein | HCW_00125, 95% | All strains, 32% in aa 93–241 |

| HCD_03280 | HEL3853 | 274 | hypothetical | HCW_00130, 94% | None |

| HCD_03315 | HEL3059 | 122 | hypothetical | HCW_00115, 89%; HCD_03265, 100% | None (2) |

| HCD_03325 | HEL3851 | 72 | hypothetical | HCW_00105, 54% | None |

| HCD_03555 | HEL3861 | 575 | hypothetical | HCW_02500, 40% in aa 1–308 & 61% in aa 410–575 (deletion, codons 309–409) | None |

| HCD_03930 | HEL3854 | 208 | hypothetical, COG0500 SAM-dependent methyltransferase | HCW_00595, 98% | None |

| HCD_04775 | HEL3270 | 422 | NADP-dependent malic enzyme | HCW_01140, 95% | None (3) |

| HCD_04915 | HEL3859 | 63 | anti-codon nuclease masking agent (fragment of >1400 aa protein) | HCW_01595, 68% (match to internal segment) | None |

| HCD_05580 | HEL3864 | 675 | OMP, HomB, pfam01856 | HCW_03170, 66%; HCW_01770, 31%; HCW_06190, 32%; HCW_03165, 32%; HCD_01070, 31%; HCD_00840, 32%; HCD_05575 | Many strains, ≤32% |

| HCD_05585 | HEL3057 | 784 | OMP, pfam01856 | HCW_02225, 50%; HCW_07955, 33%; HCW_08600, 32%; HCD_02935, 55%; HCD_00325, 33%; HCD_08430, 32%; HCD_03000, 32%; HCD_01075, 31% | Many strains, ≤28% |

| HCD_05840 | HEL3880 | 483 | OMP-2, pfam02521 | HCW_04635, 80%; HCW_06475, 39%; HCW_04640, 36%; HCW_06805, 39%; HCW_05840, 38%; HCW_05835, 34%; HCW_03775, 32%; HCW_04625, 31%; HCD_05570, 39%; HCD_06420, 39%; HCD_05545, 37%; HCD_05845, 34%; HCD_07420, 32%; HCD_05850, 32%; HCD_08485, 31%; HCD_05830, 30% | Many strains, ≤39% |

| HCD_06365 | HEL3867 | 73 | COG2608, copper (metal) binding, chaperone | HCW_03370, 60%; HCW_03375, 42%; HCD_06360, 43% | Many strains, ≤45% |

| HCD_06515 | HEL2800 | 473 | OMP, HopK, pfam01856 | HCW_05300, 52% in aa 151–473; HCD_08540, 45% in aa 47–353; HCD_02735, 58%; HCD_00320, 51% | Many strains, ≤35% in aa 281–473 |

| HCD_06965 | HEL2809 | 757 | OMP, HopF, pfam01856 | HCD_07970 54% in aa 279–834; HCD_02585, 52% in aa 584–757; HCW_07665, 66%; HCW_04920, 65%; HCW_06795, 65%; HCW_06910, 52% | Many strains, ≤42% in aa 564–757 |

| HCD_07210 | HEL3071 | 207 | hypothetical | HCW_03525, 50%; HCW_01920, 40%; HCW_07510, 43%; HCD_00640, 41% | Two strains, 42%; and 45% in aa 88–207 |

| HCD_07600 | HEL3062 | 72 | hypothetical | HCW_04310, 88% | None |

| HCD_07610 | HEL3625 | 434 | hypothetical | HCW_04320, 80%, but 603 aa (has internal replacement of 67 by 235 aa) | Many strains, ≤35%, most from aa 36 or 97 to aa 315 |

| HCD_07625 | HEL3894 | 108 | hypothetical | HCW_08150, 80% | None |

| HCD_07645 | HEL3875 | 69 | hypothetical, type III restriction | HCW_04375, 94% | Many, ≤43% in aa 19–58 |

| HCD_07680 | HEL3876 | 110 | hypothetical, COG0841,cation efflux, TrBC2/VirB2 family | HCW_04410, 80% | |

| HCD_07685 | HEL3878 | 237 | hypothetical | HCW_04415, 96% | None |

| HCD_08025 | HEL3884 | 375 | OMP-3 | HCW_07065, 61%; HCW_07110, 45% in aa 125–375; HCW_07075, 50% in aa 127–375; HCW_07105, 33%; HCW_07115, 36% in aa 83–328; HCW_04520, 31%; HCD_02500, 41% in aa 127–375; | Many strains, ≤45% in aa 127–375 |

| HCD_08210 | HEL3887 | 133 | CRISPR/Cas system protein Cas10 | HCW_07130, 46% | None |

| HCD_08220 | HEL3886 | 195 | CRISPR/Cas system RAMP superfamily protein Cas6 | HCW_07125, 91% | None (4) |

| HCD_08225 | HEL3885 | 60 | CRISPR/Cas system protein | HCW_07120, 83% (aa 69–128 of 128 aa long protein) | None (5) |

| HCD_08310 | HEL3062 | 72 | hypothetical | HCW_04310, 88% | None |

| HCD_08345 | HEL3061 | 242 | hypothetical | HCD_07575, 100%; HCW_04280, 51% in aa 1–154 (167 aa long protein) | None |

| HCD_08360 | HEL3874 | 332 | integrase | HCW_04255, 92% | Many strains, ≤38% |

| HCD_08365 | HEL3873 | 113 | hypothetical | HCW_04250, 95% | None |

| HCD_08370 | HEL3872 | 74 | hypothetical | HCW_04245, 93% | None |

| HCD_08385 | HEL3871 | 153 | hypothetical | HCW_04220, 74%; HCW_05395, 78% in aa 11–65 | Two strains, 80% in aa 5–63 |

| HCD_08390 | HEL3872 | 108 | hypothetical | HCW_08195, 83%; HCW_04200, 82% | None |

| HCD_08395 | HEL3870 | 147 | hypothetical | HCW_04215, 97% | None |

| HCD_08400 | HEL3869 | 340 | hypothetical | HCW_04205, 92%; HCW_02210, 75% in aa 182–299 (127 aa protein) | None |

| HCD_08430 | HEL3058 | 812 | OMP, HomB, pfam01856 | HCW_08600, 54%; HCW_07955, 39%; HCD_03000, 79%; HCD_00325, 47%; HCD_01285, 31% | Many, ≤33% in aa 216–812 |

| HCD_08520 | HEL3891 | 179 | hypothetical | HCW_07625, 67%; HCD_03555, 31% in aa 70–178 | None |

| HCD_08525 | HEL3073 | 58 | COG0790 FOG Sel1 repeat c102723 | HCW_07635, 74% and HCW_07630, 69% in aa 4–58. Homologs have 17 and 34 aa N-terminal extensions | None |

| HCD_08540 | HEL2800 | 331 | membrane, protein export, secD | No close HCW homolog. HCD_02735, 100% in aa 2–300; HCD_06515, 47% in aa 2–330; HCD_00320, 37% in aa 1–330 | None |

| HCD_08595 | HEL3858 | 291 | COG0338 DNA adenine methylase | HCW_01270, 89%; | Several strains with aa identities of 31%–71% |

–40% in multiple strains of Actinobacillus, Leptotrichia, Haemophilus, Morganella, Providencia, etc.(1) Homologs of HCD_02790 with aa identities of 35

H. felis, H. bizzozeronii, and H. fennelliae.(2) Distant homologs of HCD_03265 and HCD_03315 in

Campylobacter strains.(3) Homologs of HCD_04775 in many

H. pullorum, H. cinaedi and Campylobacter gracilis.(4) Homologs of HCD_08220 in several species including

Campylobacter and Helicobacter species.(5) Homologs of HCD_08225 in several

Figure 3. Schematic representation of cysteine and methionine metabolism (based on KEGG pathway 00270).

In blue, reactions predicted in H. cetorum but not H. pylori with locus tags of the unique H. cetorum rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase gene indicated. In red, reactions predicted in H. pylori but not H. cetorum. In black, reactions predicted in both H. cetorum and H. pylori. A reaction for which no predicted enzymes were found in Helicobacter genomes is indicated by the dotted line and arrowheads in gray. Of note, DNA sequences matching those of HP1045 (acetyl CoA synthetase) are missing by BLASTN criteria from each H. cetorum strain, and also from 14 of the 48 fully sequenced H. pylori genomes screened. HP1045 was not included in Table 5 because of its absence from a significant minority of H. pylori strains.

Figure 4. Schematic representation of pyruvate metabolism (based on KEGG pathway 00620).

In blue, reactions predicted in H. cetorum but not H. pylori, with locus tags of the unique H. cetorum malate dehydrogenase indicated. In red, reactions predicted in H. pylori but not H. cetorum. In black, reactions predicted in both H. cetorum and H. pylori. In green, a reaction predicted only in the H. cetorum whale strain, not in the dolphin strain, nor in H. pylori.

Table 5. H. pylori strain 26695 proteins(1) belonging to 22 GOs in H. pylori/H. acinonychis clade not in H. cetorum.

| H. pylori 26695 Locus_tag(1) | GO | NCBI annotation (H. pylori 26695) |

| HP0085 | HEL2215 | Hypothetical protein |

| HP0092 | HEL1980 | Type II restriction enzyme M protein (HsdM) |

| HP0104 | HEL2216 | 2′,3′-cyclic-nucleotide 2′-phosphodiesterase |

| HP0105 | HEL2077 | S-ribosylhomocysteinase (LuxS) |

| HP0106 | HEL2078 | Cystathionine gamma-synthase/cystathionine beta-lyase (MetB |

| HP0309 | HEL2219 | N-carbomoyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase (2) |

| HP0311 | HEL2220 | Hypothetical protein |

| HP0312 | HEL2221 | ATP-binding protein |

| HP0338 | HEL2222 | Hypothetical protein |

| HP0614 | HEL2224 | Hypothetical protein |

| HP0630 | HEL2096 | NAD(P)H-quinone reductase (MdaB) |

| HP0690 | HEL2098 | Acetyl Co A acetyltransferase |

| HP0691 | HEL2099 | Succinyl-CoA-transferase subunit A |

| HP0692 | HEL2191 | Succinyl-CoA-transferase subunit B (3) |

| HP0696 | HEL2100 | Acetone carboxylase alpha subunit |

| HP0697 | HEL2226 | Acetone carboxylase gamma subunit |

| HP0730 | HEL2227 | membrane protein (2) |

| HP0851 | HEL2107 | Pap2-like membrane protein (2) |

| HP0871 | HEL2229 | CDP-diacylglycerol pyrophosphatase |

| HP0879 | HEL2230 | Putative nuclease (2) |

| HP0935 | HEL2200 | Putative N-acyltransferase (2) |

| HP1177 | HEL1225 | Outer membrane protein (HopQ) |

| HP1185 | HEL2045 | Sugar efflux transporter |

(1) Gene names from original (1997) genome sequence deposition (NC_000915.1). The NCBI database also contains a recent deposition of a separately determined 26695 genome sequence with entirely different gene numbers (CP003904.1).

(2) Designated as hypothetical in original 1997 publication; the function indicated here was suggested by other groups analyzing corresponding sequences in other strains.

H. pylori genomes inspected (Table 1), although its protein product was not identifiied in annotations of Shi417 and XZ274 because of apparent frameshift or nonsense mutations, which we suspect may result from DNA sequencing errors.(3) The HP0692 gene sequence is present in all

Also of note are H. cetorum genes for an integrase, DNA restriction-modification, CRISPR/cas (anti-phage defense) systems, and metal (copper) binding, and numerous outer membrane proteins (OMPs; discussed further below) (Tables 3 and 4). For some of these, no homologs at all are found by BLASTP analyses in current H. pylori sequence databases. Many of the OMPs, however, are mosaic, with some segments well matched to those in H. pylori next to segments that are so divergent that we postulate functional differences, e.g., in their molecular or host cell targets or interaction partners. We suggest that many of the present strain-specific H. cetorum genes or gene fragments had been transferred from unrelated phyla, and that Helicobacter spp. adaptation to particular hosts can involve acquisition or loss of specific metabolic pathways, as was suggested during H. bizzozeronii genome analysis [31].

Genes Likely to be Involved In Bacterial-Host Interaction

Genes implicated in bacterial host interactions and that differ markedly between H. cetorum and H. pylori, that are absent from H. cetorum, or that are present in H. cetorum but not H. pylori merit special attention.

vacA

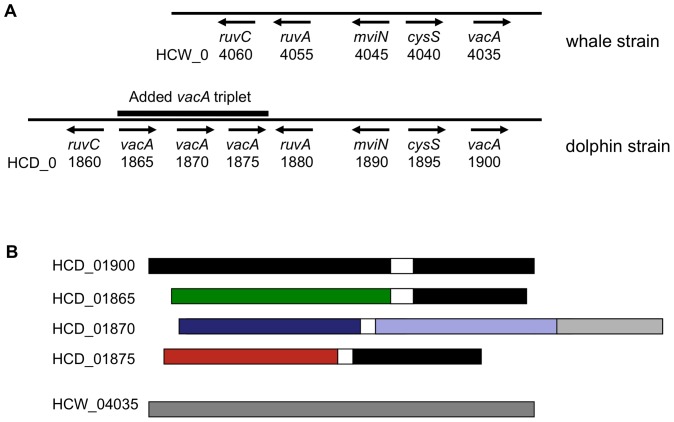

H. pylori strains encode a potent vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) that contributes to bacterial fitness and can cause multiple structural and functional changes in host tissues — prominent among them, formation of anion-selective channels and cytoplasmic vacuoles, increased permeability of cell monolayers and mitochondrial membranes, and interference with antigen presentation, inflammatory responses and immune cell activation and proliferation [32]–[35]. To our knowledge, no intact vacA genes have been found in species other than H. pylori. vacA sequences are found in H. acinonychis, but only as fragmented pseudogenes in each of the several strains examined [14], [36]). In contrast, the two H. cetorum strains each contain intact vacA homologs next to cysS, the location also occupied in H. pylori (HCD_01900, 1342 codons, and HCW_04035, 1316 codons, in dolphin and whale strains, respectively). These H. cetorum vacA genes exhibit only 60%–68% protein-level identity to their most closely related H. pylori homologs, and only ∼66% identity to one another (Figure 5).

Figure 5. vacuolating cytotoxin (vacA) genes of H. cetorum.

A, Chromosomal region containing vacA genes from the H. cetorum whale and dolphin strains. Arrows indicate gene orientation. B, Sequence conservation and divergence among vacA genes of H. cetorum. Lighter and darker shades of same color indicate ≥60% identity by BLASTP criteria. Completely different colors (black, green, blue, red) indicate ≤51% identity. To illustrate, amino acids (aa) 130–881 of gene HCD_01900 (vacA at normal location next to cysS) exhibit 40%, 50% and 65% identity to corresponding regions of HCD_01865, HCD_01875 and HCW_05035, respectively, and also 34–46% identity to corresponding regions of HCD_01870 (which itself has an internal divergent duplication with aa 1–694, just 67% identical to aa 734–1428). In contrast, aa 920–1342 of HCD_01900 exhibit 99% identity to corresponding carboxy terminal regions of HCD_01865 and HCD_01875, although only 58% and 69% identity to corresponding regions of HCD_01870 and HCW_04035. Similarly, the amino terminal ∼720 aa of HCD_01865 and HCD_01875 are each ≤50% identical to corresponding regions of other VacA proteins, whether from H. cetorum or H. pylori.

The dolphin strain contains, in addition, an extraordinary extra triplet of contiguous but divergent vacA genes (HCD_01865, HCD_01870, HCD_01875) inserted 6.5 kb from the cysS-linked vacA gene (HCD_01900) between two DNA repair/recombination genes, ruvA and ruvC, which are adjacent to one another in the whale strain (Figure 5A) (and curiously, adjacent or very near to one another in six of 16 genome sequenced H. pylori strains screened, including four strains from Africa). The dolphin strain's four vacA genes exhibit only 40% to 51% protein level identity to one another in the first ∼700–800 codons, a region important for VacA protein's secretion and multiple host cell intoxication functions [32]–[35]. In contrast, the protein from the first and third triplet members and the cysS-linked gene are 99% identical to one another in the last ∼340 amino acids (which determine VacA's autotransporter activity), but these well matched sequences are only 70% identical to the corresponding segment from the second member of the triplet (HCD_01870). The second triplet member's protein also contains an unusual divergent duplication of nearly 700 amino acids whose two components are only 67% identical to one another (Figure 5). The vacA triplet members each seem to lack ≥80 codons corresponding to 5′-ends of typical toxigenic H. pylori homologs (Figure 5) and thus may not be functional. Nevertheless these extra genes may contribute novel sequences and functionalities to other vacA genes by intragenic recombination. Just how these various vacA alleles affect the transport, actions and interactions of their encoded proteins, and bacterial virulence, host range and host responses to infection all merit further study.

H. pylori strains typically contain several genes annotated as toxin-like or vacA-like because the C-terminal autotransporter domains of their encoded proteins exhibit ∼30% identity to that of VacA. The H. cetorum strains also contain several such toxin-like genes, including one with ≥65% protein-level identity to H. pylori imaA (HP0289), found recently to help modulate host inflammatory responses to infection [37].

cag PAI and adjacent HP0159 gene

Each H. cetorum strain lacks a cag pathogenicity island (cag PAI), a ∼30 kb DNA segment present in more than half of H. pylori strains worldwide that is a major contributor to infection-associated inflammation and changes in epithelial structure and development, and that is disease-associated epidemiologically and a contributor to H. pylori fitness and virulence in cell culture and animal infection models [38]–[42]. Also absent is a close homolog of gene HP0519, which is next to one cag PAI end in cag-positive H. pylori, seems to have undergone intense selection for amino acid sequence change in certain populations, and is suspected of helping manage host responses to infection [23], [43]. Homologs of genes that flank the HP0519-cag PAI cluster in H. pylori are next to each other in both H. cetorum strains (e.g., HCD_05445 and HCD_05440; and HCW_05215 and HCW_05220); it is not known whether H. cetorum had never obtained a cag PAI or HP0519, vs. if this DNA segment was lost by deletion.

Extra urease genes

Stomach-colonizing Helicobacter species produce a urease that hydroylzes urea using nickel as a cofactor, and that is essential for gastric infection [44]. Remarkably several species from carnivore hosts each produce an additional urease, cofactored by iron rather than nickel [H. acinonychis (big cats), H. felis (domestic cats and dogs), and H. mustelae (ferrets)] [45], [46]. The two H. cetorum strains also contain genes for both iron- and nickel-cofactored ureases – for example, in the dolphin strain, genes HCD_02705 and HCD_02710, 94% and 97% protein level identity to H. acinonychis ureA2 and ureB2 (iron) and HCD_03580 and HCD_03585, ∼94% and ∼98% identity to H. pylori ureA and ureB (nickel). Equivalent homologs are found in the whale strain. Since nickel is limiting and iron is abundant in meat, an iron-cofactored urease is considered adaptive for carnivore infection [45], [46] (although H. heilmannii sensu stricto and H. bizzozeronii, which infect cats and dogs, respectively, have only a nickel-dependent urease).

Sel1-like repeat (slr) family genes

Seven and nine members of the divergent slr gene family, whose encoded products are secreted, and contain one or more copies of a motif characteristic of Sel1-type eukaryotic regulatory factors, were found in the dolphin and whale strain, respectively. The three best known H. pylori SLR proteins are: HcpA, which may modulate immune responses to infection by stimulating the release of cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12, and differentiation of Thp1 monocytes to macrophages [47]; HcpC, which facilitates GroEL chaperone and urease translocation to the bacterial surface, and stimulates H. pylori growth in mammalian cell cultures [48] and also interacts with eukaryotic protein kinase Nek9 (implicated in eukaryotic cell cycle regulation) [49]; and HP0519, which, as noted above, has undergone intense selection for amino acid change in particular human populations [23], [43]. Of these, only genes closely related to hcpC were found in H. cetorum genomes (genes HCD_08435 and HCW_08325; 86% and 79% protein level identity, respectively, to closest H. pylori hcpC homologs), although the C terminal 150 codons of HCD_03275 and HCW_00125 exhibit ∼32% protein level identity to corresponding regions of H. pylori HcpA.

Virulence-associated Leptospira/Bartonella paralog gene family

A remarkable multigene family implicated in pathogenesis in species of Leptospira and Bartonella (PF07598; up to 12 divergent copies in the most virulent strains) [50] is represented by one distant homolog in each H. cetorum strain (HCW_01460 and HCD_04445). No member of this family is found in any of the many dozens of H. pylori strains genome sequenced to date. Just how this gene family can contribute to infection, virulence or other phenotypes that increase fitness is not yet known.

Outer membrane protein (OMP) genes

The H. cetorum strains each contain 78 or more putative OMP genes, whose various functions should include bacterial adherence to host tissues, uptake of ions, solutes and larger molecules; export of effectors and toxic metabolites, antimicrobial resistance, outer membrane assembly, etc. This gene number compares with the approximately 64 OMP genes found in annotations of H. pylori genomes [51, and unpublished]. A first-pass BLASTP comparison indicates that the most closely matched OMP pairs from the two H. cetorum strains tend to be very divergent from one another. For example, the median level of identity of whale strain OMPs to the most closely related dolphin strain homologs is only about 62%, with a range from 0% (no significant homolog) to >86% in the 35 representative proteins screened. This contrasts with the median ∼95% identity (>90% identity of some 84% of individual H. pylori OMPs) between unrelated H. pylori strains such as 26695 and J99 [51]. Superimposed on this diversity, many H. cetorum OMPs are more related to other OMPs in the same strain than to any homolog in the other strain; and many pairs of H. cetorum OMPs, although ≥80% identical in C terminal ∼200 amino acids, exhibit <30% sequence identity in their more central segments, which are likely to mediate interactions with other molecules or cells. In H. pylori such central region protein divergence patterns is typical of OMPs encoded by different genes, not products of strain-specific alleles of the same OMP gene. These divergences suggest OMP gene transfer from other bacterial phyla and/or different selective forces once these genes appeared in H. cetorum lineages, which, in turn, may have led to significantly different spectra of OMP functions in the two strains and affected cell type or host specificity.

Competence Genes

The three separate clusters of genes needed collectively for H. pylori DNA transformation (genes HP0014-HP0018 = comB1-comB5; HP0036-HP0042 = comB6-comB10; and dprA and dprB) are present in H. cetorum genomes. The comB-encoded type IV secretion system is used in recipient cells to facilitate DNA transfer by bacterial conjugation [52]. DprA protein binds DNA and can help protect it from restriction and stimulate its methylation [53]. The presence of these genes supports ideas of DNA exchange as a force in H. cetorum evolution.

Transposable Elements

Distributions of bacterial transposable elements reflect patterns of horizontal DNA transfer (genetic exchange) in populations. Three distinct classes are known in Helicobacter: 1) the IS605 family of IS elements, whose five known types are each ∼2 kb long and contain a transposase gene (orfA) and one or two auxiliary genes of unknown function [54]–[57]; 2) the ∼40 kb TnPZ “plasticity zone” transposons, which contain genes implicated epidemiologically in virulence in some human populations [22], and also genes for a type IV secretion system (tfs3) and for a novel putative integrase protein (xerT) [22], [58]; 3) inducible plaque-forming prophages, found in a few East Asian H. pylori strains [59], [60] and remnants of them found in some other strains [14, 61, and present analyses].

The dolphin strain chromosome contains two IS605 family members — one copy of an element closely related to IS605 itself, plus 20 nearly identical copies of an IS606-type element (∼82% DNA identity to H. pylori IS606) [54]. Also present are multiple fragments of a TnPZ element plus more than 20 fragments with significant matches to 1961P-type H. pylori phages [59], [60]. Among these are three near perfect repeats of fragments with lengths of ∼631 bp, 908 bp and 1260 bp in four, two and three locations, respectively, in the dolphin strain chromosome.

The whale strain chromosome, in contrast, lacks IS605-family elements, and contains two apparently complete TnPZ elements, one classified as “type 2” based on gene order and 80–85% DNA identity to H. pylori type 2 TnPZs described in [22], and another that could be considered a type 1/type 2 hybrid or a third TnPZ transposon type [22]. Also present is a 39 kb sequence that contains most genes found in the 1961P phage group (from genes HCW_02700 through HCW_02905). The first 19 kb consists of a relatively uninterrupted set of homologs of phage 1961P genes gp1 to gp18 [59] (HCW_02700 to HCW_02770), whereas the remaining ∼20 kb contain homologs of known phage genes interspersed with other (probably bacterial) genes in an order that is scrambled relative to that in 1961P and related plaque forming phages.

Plasmids

The dolphin and whale H. cetorum strains contain partially related plasmids, 14.1 kb and 12.5 kb in length, respectively. Some 40% of the smaller whale strain plasmid exhibits 71%–92% DNA identity to the larger dolphin strain plasmid and contains genes implicated in plasmid DNA replication; the other 60% of this plasmid is absent by BLASTN criteria from the dolphin strain plasmid. Among features unique to the dolphin strain plasmid are (i) genes provisionally classified as encoding NTPase – DNA partitioning (HCD_08789), DNA nicking (nikB, HCD_08804) and DNA mobilization (mobC, HCD_08799) functions, which suggests that the plasmid might be readily transferred to other bacterial strains; and (ii) a direct non-tandem repeat of IS606 elements that are nearly identical to those in the chromosome.

The fragmentation of prophages in both strains suggests ancient phage infection and lysogenization event(s); in contrast, the number and homogeneity of the dolphin strain's IS606 elements suggests evolutionarily recent introduction and rapid copy number expansion by tranposition.

Discussion

We sequenced the genomes of two strains of H. cetorum, a taxonomic group that infects marine mammals worldwide and that, based on 16 S rDNA sequences, seemed most closely related to the human gastric pathogen H. pylori and its derivative from big cats, H. acinonychis. Our genome sequences and analyses of shared genes confirm this close relationship genome-wide. That said, less than three-fourths of whale and dolphin strain genome sequences are found by BLASTN default criteria in H. pylori genome sequences. In addition, these strains differ remarkably from one another in: (i) sequences of many shared genes, (ii) overall content of strain-specific DNAs, and (iii) chromosomal gene arrangement. These differences are far more pronounced than are seen with strains of H. pylori, which is generally considered one of the most genetically diverse of bacterial species. Further studies, especially using additional H cetorum strains from various hosts and geographic regions are needed to learn if the two strains studied here represent different discrete groups that perhaps should be designated as separate species, vs. simply points on a genetic continuum of one extraordinarily diverse species. In considering this issue, we note that the traditional species concept as developed for higher organisms is poorly suited to bacteria. This is because many bacterial phyla have rich histories of DNA transfer from unrelated groups, superimposed on reproduction by clonal growth without need for gene exchange [62].

Multiple features distinguish the genomes of these H. cetorum strains from those of H. pylori and H. acinonychis, most prominently: (i) their positions in a phylogenetic tree based on sequences of shared core genes (Figure 1); and (ii) the 36% of the whale strain and 26% of the smaller dolphin strain genomes not found in H. pylori genomes by Mega BLASTN criteria. Such features suggest H. cetorum genome evolution driven by horizontal DNA transfer from other phyla, in addition to in situ mutation, selection for adaptive change and genetic drift. Supporting this view are differences in metabolic enzymes illustrated in Figures 3 and 4; OMPs and other proteins likely to participate directly in bacterial host interaction; and contents of mobile DNAs (the IS605-family elements, TnPZ transposons and prophage remnants). We note, in particular the differences in ∼80 putative outer membrane proteins, many of which may participate in adherence and signaling to host tissues, uptake or export of ions and molecules, and membrane synthesis (Tables 3 and 4); and also the remarkably divergent alleles of the vacA (vacuolating cytotoxin) gene in the usual location next to cysS and in the dolphin strain's extra triplet of vacA genes inserted nearby (Figure 5). The most intense divergence among the various H. cetorum VacA proteins is in the first ∼700–800 amino acids, which in well characterized VacA proteins, contains a signal sequence needed for VacA secretion and determinants of the protein's multiple host cell intoxication activities [32]–[35]. Future studies may reveal novel functionalities of these various vacA alleles, how their divergent sequences affect the transport, actions and interactions of their encoded proteins, and the selective forces that drive their evolution.

Metabolic differences also merit particular attention: Prominent among them are H. cetorum's rhodonase sulfurtransferase, which may catalyze synthesis of pyruvate and thiosulfate from 3-mercaptopyruvate (Figure 3; blue arrows). These sulfurtransferases are related to enzymes found in diverse genera including Haemophilius and Actinobacillus, but in few if any other members of the Epsilonproteobacteria. A second example is provided by H. cetorum's distinctive NADP-dependent malic enzyme, which should catalyze production of L-malate from pyruvate (Figure 4, blue arrows), and whose homologs occur in multiple extragastric Helicobacter spp, but not in H. pylori. Also noteworthy are the metabolic enzymes found in H. pylori but not H. cetorum: in particular those for synthesis of L-homocysteine and conversion of L-cysteine to thiocysteine or pyruvate (Figures 3; red arrows); and those for syntheses of acetoacetyl-CoA and acetate from acetyl-CoA, and of acetoacetate from acetoacetyl-CoA (Figure 4; red arrows). Finally we note the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (production of oxaloacetate from phosphoenolpyruvate) in the whale but not the dolphin strain (Figure 4; green arrow). Although direct experimental analyses are needed to fully understand these enzymes and their actions and importance in vivo, our findings fit with a suggestion, made while describing H. bizzozeronii [31], that Helicobacter adaptation to particular hosts could in part involve acquisition or loss of specific metabolic pathways,

Many additional features of interest to particular readers will be found in our two H. cetorum genome sequences, which should also aid further analyses of issues such as: (i) this species' great diversity and how these microbes have adapted for chronic infection of their various marine mammal hosts; (ii) how genetically interconnected or separate H. cetorum populations from different oceans or host species may be; (iii) mechanisms of H. cetorum transmission within and among host species; (iv) host ranges and factors that determine host specificity; (v) the relative importance for H. cetorum strain genetic divergence of mutation and horizontal gene transfer, and of selection for adaptive change and genetic drift (e.g., due to specialization for different host species or the vastness of the world's oceans); and (vi) finally the pathogenic vs. benign or beneficial interactions of H. cetorum strains with their various hosts, an issue of particular interest in today's fragile marine ecosystems.

Supporting Information

*Annotation from H. pylori 26695 NCBI BioProject PRJNA178201.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr James Fox for H. cetorum strains, MOGene Corp, St Louis, MO for high quality 454 sequencing and assembly, and Drs Timothy Cover and Peer Mittl for stimulating discussion, and Ms Sravya Tamma for help with BLAST analyses.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health R21 AI078237 and R21 AI088337. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Lee A, O′Rourke J (1993) Gastric bacteria other than Helicobacter pylori . Gastroenterol Clin North Am 22: 21–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solnick JV, Vandamme P (2001) Taxonomy of the Helicobacter Genus. In: Mobley HLT, Mendz GL, Hazell SL, editors. Helicobacter pylori: Physiology and Genetics. Washington (DC): ASM Press; 2001. Chapter 5. pp 39–52

- 3. Blanchard TG, Nedrud JG (2012) Laboratory maintenance of Helicobacter species. Curr Protoc Microbiol. Chapter 8: Unit8B.1 DOI: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc08b01s24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cover TL, Blaser MJ (2009) Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology 136: 1863–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamaoka Y (2010) Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 7: 629–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suerbaum S, Josenhans C (2007) Helicobacter pylori evolution and phenotypic diversification in a changing host. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Herrera PM, Mendez M, Velapatiño B, Santivañez L, Balqui J, et al. (2008) DNA-level diversity and relatedness of Helicobacter pylori strains in shantytown families in Peru and transmission in a developing-country setting. J Clin Microbiol 46: 3912–3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harper CG, Feng Y, Xu S, Taylor NS, Kinsel M, et al. (2002) Helicobacter cetorum sp. nov., a urease-positive Helicobacter species isolated from dolphins and whales. J Clin Microbiol 40: 4536–4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harper CG, Xu S, Rogers AB, Feng Y, Shen Z, et al. (2003) Isolation and characterization of novel Helicobacter spp. from the gastric mucosa of harp seals Phoca groenlandica . Dis Aquat Organ 57: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldman CG, Matteo MJ, Loureiro JD, Almuzara M, Barberis C, et al. (2011) Novel gastric helicobacters and oral campylobacters are present in captive and wild cetaceans. Vet Microbiol 152: 138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goldman CG, Matteo MJ, Loureiro JD, Degrossi J, Teves S, et al. (2009) Detection of Helicobacter and Campylobacter spp. from the aquatic environment of marine mammals. Vet Microbiol 133: 287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldman CG, Loureiro JD, Matteo MJ, Catalano M, Gonzalez AB, et al. (2009) Helicobacter spp. from gastric biopsies of stranded South American fur seals (Arctocephalus australis). Res Vet Sci 86: 18–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McLaughlin RW, Zheng JS, Chen MM, Zhao QZ, Wang D (2011) Detection of Helicobacter in the fecal material of the endangered Yangtze finless porpoise Neophocaena phocaenoides asiaeorientalis . Dis Aquat Organ 95: 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eppinger M, Baar C, Linz B, Raddatz G, Lanz C, et al. (2006) Who ate whom? Adaptive Helicobacter genomic changes that accompanied a host jump from early humans to large felines. PLoS Genet 2: e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. García-Amado MA, Al-Soud WA, Borges-Landaéz P, Contreras M, Cedeño S, et al. (2007) Non-pylori Helicobacteraceae in the upper digestive tract of asymptomatic Venezuelan subjects: detection of Helicobacter cetorum-like and Candidatus Wolinella africanus-like DNA. Helicobacter 12: 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wittekindt NE, Padhi A, Schuster SC, Qi J, Zhao F, et al. (2010) Nodeomics: pathogen detection in vertebrate lymph nodes using meta-transcriptomics. PLoS One 18: e13432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frias-Lopez J, Zerkle AL, Bonheyo GT, Fouke BW (2002) Partitioning of bacterial communities between seawater and healthy, black band diseased, and dead coral surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 2214–2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Webster NS, Xavier JR, Freckelton M, Motti CA, Cobb R (2008) Shifts in microbial and chemical patterns within the marine sponge Aplysina aerophoba during a disease outbreak. Environ Microbiol 10: 3366–3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sweet M, Bythell J (2012) Ciliate and bacterial communities associated with White Syndrome and Brown Band Disease in reef-building corals. Environ Microbiol 14: 2184–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakagawa S, Takaki Y, Shimamura S, Reysenbach AL, Takai K, et al. (2007) Deep-sea vent epsilon-proteobacterial genomes provide insights into emergence of pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 12146–12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beinart RA, Sanders JG, Faure B, Sylva SP, Lee RW, et al. (2012) Evidence for the role of endosymbionts in regional-scale habitat partitioning by hydrothermal vent symbioses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E3241–3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kersulyte D, Lee W, Subramaniam D, Anant S, Herrera P, et al. (2009) Helicobacter pylori's plasticity zones are novel transposable elements. PLoS One 4: e6859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kersulyte D, Kalia A, Gilman RH, Mendez M, Herrera P, et al. (2010) Helicobacter pylori from Peruvian Amerindians: traces of human migrations in strains from remote Amazon, and genome sequence of an Amerind strain. PLoS One 5: e15076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS (2003) OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res 13: 2178–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Katoh K, Standley DM (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abascal F, Zardoya R, Telford MJ (2010) TranslatorX: multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic Acids Res 38 (Web Server issue):W7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27. Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, et al. (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59: 307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A (2000) EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends in Genetics 16: 276–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk H-P, Göker M (2013) Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics 14 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baltrus DA, Amieva MR, Covacci A, Lowe TM, Merrell DS, et al. (2008) The complete genome sequence of Helicobacter pylori strain G27. J Bacteriol 191: 447–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schott T, Kondadi PK, Hänninen ML, Rossi M (2011) Comparative genomics of Helicobacter pylori and the human-derived Helicobacter bizzozeronii CIII-1 strain reveal the molecular basis of the zoonotic nature of non-pylori gastric Helicobacter infections in humans. BMC Genomics 12: 534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cover TL, Blanke SR (2005) Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nat Rev Microbiol. 3: 320–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chambers MG, Pyburn TM, González-Rivera C, Collier SE, Eli I, et al. (2013) Structural analysis of the oligomeric states of Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin. J Mol Biol 425: 524–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gangwer KA, Shaffer CL, Suerbaum S, Lacy DB, Cover TL, et al. (2010) Molecular evolution of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin gene VacA. J Bacteriol 192: 6126–6135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim IJ, Blanke SR (2012) Remodeling the host environment: modulation of the gastric epithelium by the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA). Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dailidiene D, Dailide G, Ogura K, Zhang M, Mukhopadhyay AK, et al. (2004) Helicobacter acinonychis: Genetic and rodent infection studies of a Helicobacter pylori-like gastric pathogen of cheetahs and other big cats. J Bacteriol 186: 356–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sause WE, Castillo AR, Ottemann KM (2012) The Helicobacter pylori autotransporter ImaA (HP0289) modulates the immune response and contributes to host colonization. Infect Immun 80: 2286–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fischer W, Prassl S, Haas R (2009) Virulence mechanisms and persistence strategies of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori . Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 337: 129–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Backert S, Selbach M (2008) Role of type IV secretion in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol 10: 1573–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atherton JC (2006) The pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastro-duodenal diseases. Annu Rev Pathol 63–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41. Wroblewski LE, Peek RM Jr, Wilson KT (2010) Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clin Microbiol Rev 23: 713–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tan S, Noto JM, Romero-Gallo J, Peek RM Jr, Amieva MR (2011) Helicobacter pylori perturbs iron trafficking in the epithelium to grow on the cell surface. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ogura M, Perez JC, Mittl PR, Lee HK, Dailide G, et al. (2007) Helicobacter pylori evolution: lineage-specific adaptations in homologs of eukaryotic Sel1-like genes. PLoS Comput Biol 3: e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sachs G, Weeks DL, Melchers K, Scott DR (2003) The gastric biology of Helicobacter pylori. Annu Rev Physiol 65: 349–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stoof J, Breijer S, Pot RG, van der Neut D, Kuipers EJ, et al. (2008) Inverse nickel-responsive regulation of two urease enzymes in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter mustelae . Environ Microbiol 10: 2586–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carter EL, Tronrud DE, Taber SR, Karplus PA, Hausinger RP (2011) Iron-containing urease in a pathogenic bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 13095–13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dumrese C, Slomianka L, Ziegler U, Choi SS, Kalia A, et al. (2009) The secreted Helicobacter cysteine-rich protein A causes adherence of human monocytes and differentiation into a macrophage-like phenotype. FEBS Lett 583: 1637–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Putty K, Marcus SA, Mittl PRE, Bogadi LE, Hunter AM, et al. (2013) Robustness of Helicobacter pylori infection conferred by context-variable redundancy among cysteine-rich paralogs. PLoS ONE 8: e59560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roschitzki B, Schauer S, Mittl PR (2011) Recognition of host proteins by Helicobacter cysteine-rich protein C. Curr Microbiol 63: 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lehmann JS, Fouts DE, Haft DH, Cannella AP, Ricaldi JN, et al. (2013) Pathogenomic Inference of Virulence-Associated Genes in Leptospira interrogans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rohrer S, Holsten L, Weiss E, Benghezal M, Fischer W, et al. (2012) Multiple pathways of plasmid DNA transfer in Helicobacter pylori . PLoS One 7: e45623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dwivedi GR, Sharma E, Rao DN (2013) Helicobacter pylori DprA alleviates restriction barrier for incoming DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 3274–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Alm RA, Bina J, Andrews BM, Doig P, Hancock RE, et al. (2000) Comparative genomics of Helicobacter pylori: analysis of the outer membrane protein families. Infect Immun 68: 4155–4168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kersulyte D, Akopyants NS, Clifton SW, Roe BA, Berg DE (1998) Novel sequence organization and insertion specificity of IS605 and IS606: chimaeric transposable elements of Helicobacter pylori . Gene 223: 175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kersulyte D, Mukhopadhyay AK, Shirai M, Nakazawa T, Berg DE (2000) Functional organization and insertion specificity of IS607, a chimeric element of Helicobacter pylori . J Bacteriol 182: 5300–5308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kersulyte D, Velapatiño B, Dailide G, Mukhopadhyay AK, Ito Y, et al. (2002) Transposable element ISHp608 of Helicobacter pylori: nonrandom geographic distribution, functional organization, and insertion specificity. J Bacteriol 184: 992–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kersulyte D, Kalia A, Zhang M, Lee HK, Subramaniam D, et al. (2004) Sequence organization and insertion specificity of the novel chimeric ISHp609 transposable element of Helicobacter pylori . J Bacteriol 186: 7521–7258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fischer W, Windhager L, Rohrer S, Zeiller M, Karnholz A, et al. (2010) Strain-specific genes of Helicobacter pylori: genome evolution driven by a novel type IV secretion system and genomic island transfer. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 6089–6101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Luo CH, Chiou PY, Yang CY, Lin NT (2012) Genome, integration, and transduction of a novel temperate phage of Helicobacter pylori . J Virol 86: 8781–8792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Uchiyama J, Takeuchi H, Kato S, Takemura-Uchiyama I, Ujihara T, et al. (2012) Complete genome sequences of two Helicobacter pylori bacteriophages isolated from Japanese patients. J Virol 86: 11400–11401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lehours P, Vale FF, Bjursell MK, Melefors O, Advani R, et al. (2011) Genome sequencing reveals a phage in Helicobacter pylori . MBio 15: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Doolittle WF (2012) Population genomics: how bacterial species form and why they don't exist. Curr Biol 22: R451–R453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

*Annotation from H. pylori 26695 NCBI BioProject PRJNA178201.

(DOCX)