Abstract

Impairment of cognitive processes is a devastating outcome of many diseases, injuries, and drugs affecting the central nervous system (CNS). Most often, very little can be done by available therapeutic interventions to improve cognitive functions. Here we review evidence that inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) ameliorates cognitive deficits in a wide variety of animal models of CNS diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome, Parkinson's disease, spinocerebellar ataxia type 1, traumatic brain injury, and others. GSK3 inhibitors also improve cognition following impairments caused by therapeutic interventions, such as cranial irradiation for brain tumors. These findings demonstrate that GSK3 inhibitors are able to ameliorate cognitive impairments caused by a diverse array of diseases, injury, and treatments. The improvements in impaired cognition instilled by administration of GSK3 inhibitors appear to involve a variety of different mechanisms, such as supporting long-term potentiation and diminishing long-term depression, promotion of neurogenesis, reduction of inflammation, and increasing a number of neuroprotective mechanisms. The potential for GSK3 inhibitors to repair cognitive deficits associated with many conditions warrants further investigation of their potential for therapeutic interventions, particularly considering the current dearth of treatments available to reduce loss of cognitive functions.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Fragile X Syndrome, glycogen synthase kinase-3, learning, lithium, LTP

1. Introduction

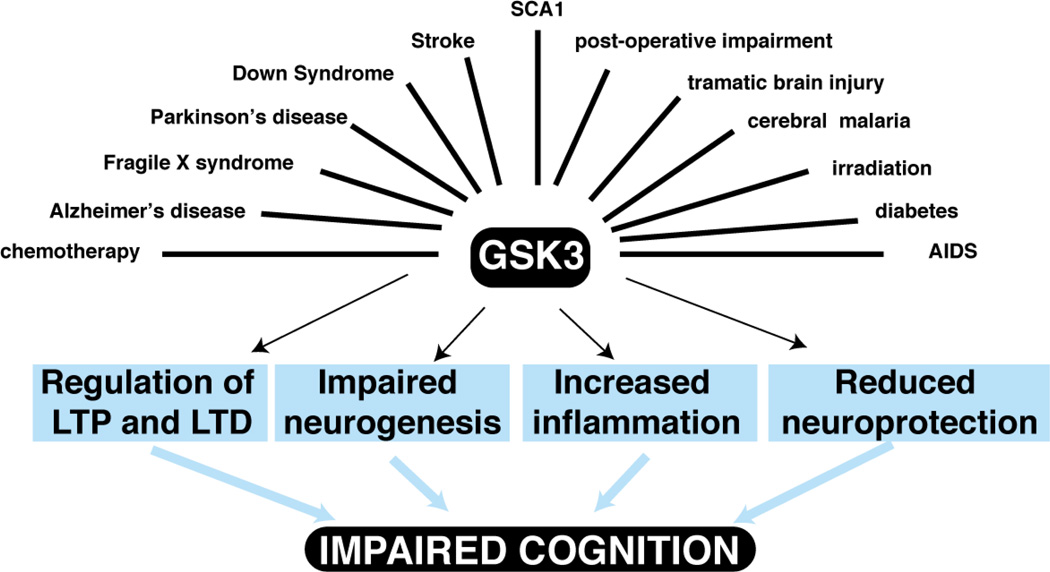

Cognitive abilities define our species and our individual identities. Yet these functions are often threatened, as it seems that nearly every neurological and psychiatric disease includes a component of cognitive disability. This is particularly true of ageing-associated diseases, which afflict an ever-increasing portion of the population. With the recognition of the importance of disease-associated cognitive disabilities, much effort, although perhaps insufficient, is being directed towards finding ways to protect and restore cognitive functions. Here we review the rapidly accumulating evidence that inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) represent one of the strongest candidate classes of agents for this purpose. Although most widely studied for their potential therapeutic actions in Alzheimer's disease (AD), in fact more than a dozen distinct conditions in rodent models involving cognitive impairments have been shown to be ameliorated by the administration of GSK3 inhibitors (Figure 1). Thus, this substantial evidence suggests that GSK3 inhibitors should be more widely considered as interventions for protecting and restoring cognitive abilities that are jeopardized in many individuals with neurological and psychiatric diseases.

Figure 1. GSK3 inhibitors improve impaired cognition in multiple conditions.

Schematic representation of conditions in which inhibition of GSK3 improves impairments in cognitive processes. The improvements in impaired cognition following administration of GSK3 inhibitors likely involve a variety of different mechanisms, such as supporting long-term potentiation and diminishing long-term depression, promotion of neurogenesis, reduction of inflammation, and increasing a number of neuroprotective mechanisms.

2. GSK3 and inhibitors

GSK3 refers to two paralogs, GSK3α and GSK3β, that are commonly referred to as isoforms because of their similar sequences and functions although they are derived from different genes and differential actions have been identified (Kaidanovich-Beilin and Woodgett, 2011). They are ubiquitously expressed, serine/threonine kinases that are involved in a large number of cellular functions (Jope and Johnson, 2004). The activity of GSK3 is most commonly regulated by phosphorylation on a regulatory serine, serine-21 in GSK3α and serine-9 in GSK3β. Phosphorylation of these regulatory serines inhibits the activity of GSK3. GSK3 can be phosphorylated on these serines by several kinases, such as Akt, protein kinase C, protein kinase A, and others. This provides a mechanism for many intracellular signaling pathways to control the activity of GSK3. However, it appears that this also provides a mechanism for disease-associated impairments in signal transduction pathways to result in failure to adequately inhibit GSK3. This failure can permit GSK3 to remain abnormally active, which appears to allow GSK3 to contribute to disease pathologies, including cognitive impairments, as discussed in later sections of this review.

The increasing evidence that GSK3 contributes to the pathology of several prevalent diseases, perhaps most notably AD and mood disorders, has generated much interest in applying GSK3 inhibitors therapeutically. Lithium was the first GSK3 inhibitor to be identified (Klein and Melton, 1996; Stambolic et al., 1996), and lithium remains the most widely used experimentally and clinically. Lithium directly binds and inhibits GSK3 (Klein and Melton, 1996; Stambolic et al., 1996), and lithium administration also increases the inhibitory serine-phosphorylation of GSK3 (Jope, 2003). Lithium is widely used therapeutically as a mood stabilizer in patients with mood disorders, and much evidence indicates that inhibition of GSK3 makes an important contribution to its mood stabilizing therapeutic effect (Jope, 2011). In human patients, therapeutic levels of lithium are in the range of 0.5–1.2 mM lithium in the serum, and this serum concentration of lithium is often achieved in rodents by administration of food pellets containing 0.2–0.4% lithium (Jope, 2001). Many actions of lithium have been shown to be due to inhibition of GSK3, but lithium also has other actions, such as inhibition of inositol monophosphatase, that should not be discounted unless the effects of lithium have been verified to be due to inhibition of GSK3 using other selective inhibitors of GSK3 or molecular manipulations of GSK3 (Phiel and Klein, 2001). The utility of lithium and therapeutic promise of GSK3 inhibitors led to the development of many selective inhibitors of GSK3 during the last decade that are beginning to be more widely used (Eldar-Finkelman and Martinez, 2011). Many of these are ATP-competitive inhibitors of GSK3, but particularly promising are GSK3 inhibitors that are not ATP-competitive, since ATP-competitive inhibitors tend to also inhibit other kinases and may prove to be more toxic. Among the frequently used ATP-competitive GSK3 inhibitors are indirubin derivatives (Leclerc et al., 2001), paullone derivatives (Leost et al., 2000), SB415286 and SB216763, although care must be taken concerning their solubilities as originally described (Coghlan et al., 2000), and AR-A014418 (Bhat et al., 2003), although the reports of behavioral effects of AR-A014418 are mitigated by other studies indicating that it does not significantly enter the CNS (Vasdev et al., 2005; Selenica et al., 2007; Hicks et al., 2010). Reports of the kinase specificities of several GSK3 inhibitors are particularly valuable (Davies et al., 2000; Murray et al., 2004; Bain et al., 2007), enabling investigators to choose multiple GSK3 inhibitors with different off-target actions. Other GSK3 inhibitors that are not competitive with the ATP binding site in GSK3 are particularly promising (Eldar-Finkelman and Martinez, 2011). L803-mts is a cell-permeable, 11 residue peptide that is a substrate-competitive specific inhibitor of GSK3 (Plotkin et al., 2003; Kaidanovich-Beilin et al., 2004; Licht-Murava et al., 2011). TDZD-8 is a highly selective ATP non-competitive inhibitor of GSK3 (Martinez et al., 2002). VP0.7 is an allosteric (not competitive with ATP or substrate) selective GSK3 inhibitor that binds to the C-terminal lobe of the enzyme (Palomo et al., 2011). Here we review the evidence for cognitive effects involving GSK3. Studies of potential actions of GSK3 in cognition have primarily utilized lithium, in part because it is the GSK3 inhibitor that has been available the longest, so reports of lithium's effects predominate in this review, but newer GSK3 inhibitors and molecular modifications of GSK3 have also been studied.

3. Effects of GSK3 inhibitors on cognition in healthy rodents and humans

3.1. Cognition in lithium-treated rodents

In contrast to the many conditions where impaired cognitive behaviors in rodents are improved by lithium treatment, which are discussed below, lithium often has been reported to have little effect on cognitive tasks in healthy rodents. For example, recent reports concluded that chronic dietary lithium treatment for several weeks did not alter performance in the Morris water maze in Wistar rats (de Vasconcellos et al., 2003; Vasconcellos et al., 2005), or in mice ranging in initial treatment age from one week to 12 months (Yazlovitskaya et al., 2006; Watase et al., 2007; Thotala et al., 2008; Sy et al., 2011). Chronic dietary lithium treatment also did not alter contextual fear conditioning in mice (Watase et al., 2007), performance in the object location test in mice (Dai et al., 2012), or contextual fear conditioning, spatial memory, novel object recognition, and T maze spontaneous alternation task in mice (Contestabile et al., 2013). Chronic dietary lithium treatment that began in adolescence (4 weeks old) and was continued for 8 weeks, or 4 weeks of dietary lithium treatment in adult mice, did not alter performance in the visual object novelty detection task, temporal ordering for visual objects task, or spatial learning in the coordinate and categorical processing tasks (King and Jope, 2013). Chronic lithium treatment (2 mmol/kg; i.p.) did not alter acquisition of a non-matching to place rule in rats (Tsaltas et al., 2007b), nor did lithium treatment (47.5 mg/kg, i.p.) alter behavior in the olfactory discrimination test, the social recognition task, or short-term and long-term memory evaluated in the step-down inhibitory avoidance task in rats (Castro et al., 2012). These findings support the older literature that cognitive tasks in rodents are often unaffected by therapeutically relevant levels of lithium. However, enhanced performance following chronic lithium treatment has been found in several studies. Chronic lithium treatment (2 mmol/kg; i.p.) of mice for several weeks improved spatial working memory in a delayed alternation T-maze task and facilitated long-term retention of passive avoidance learning (Tsaltas et al., 2007a). Chronic dietary lithium treatment increased freezing behavior in a cued fear conditioning task (Watase et al., 2007), and enhanced learning in the passive avoidance task (Yuskaitis et al 2010). Adult male rats treated with dietary lithium for 4 weeks displayed improved spatial discrimination learning in the hole-board task, increased working memory and long-term memory in the T-maze delayed alternation task and enhanced place conditioned learning in the social place-preference conditioning task (Nocjar et al., 2007). Thus, certain cognitive tasks may be improved by lithium treatment of healthy rodents, but most often lithium has been found to not significantly affect performance.

3.2. Cognition in rodents treated with other inhibitors of GSK3

Few studies have investigated the effects of GSK3 inhibitors other than lithium on cognitive behaviors in healthy rodents, and most found no effects, which is in agreement with most studies of the effects of lithium. Treatment with the GSK3 inhibitors SB216763 (0.6 mg/kg; i.p) or SB415286 (1.0 mg/kg; i.p.) for 3 days in two week old wild-type mice did not alter performance in the Morris water maze measured 2–3 months later (Thotala et al., 2008). Chronic treatment of mice with SB216763 (2 mg/kg; i.p.) every other day for 2 weeks had no effect on performance in the contextual and tone trace conditioning tests or spatial learning in the delayed non-matching-to-place radial arm maze (Guo et al., 2012). Inhibition of GSK3 with intracerebroventricular (icv) infusion of SB216763 (20 ng/µl) in rats did not affect performance in the Morris water maze (Tian et al., 2012). Acute treatment with the GSK3 inhibitors TDZD-8 (5 mg/kg; i.p.) or VP0.7 (5 mg/kg; i.p.) did not alter performance of mice in the visual object novelty detection task, temporal ordering for visual objects task, spatial learning in the coordinate and categorical processing tasks (Franklin et al., 2013).These findings match well with those of lithium treatments, in that cognitive behaviors of healthy rodents often are unaffected by administration of GSK3 inhibitors. In contrast, a report that 4 weeks of icv infusion of SB216763 (78 pmol/day) in rats impaired performance in the Morris water maze task (Hu et al., 2009) may be indicative of toxic effects of long-term central administration of an ATP-competitive inhibitor of GSK3. On the other hand, acute treatment with the dual phosphodiesterase-7 and GSK3 inhibitor VP1.15 (3 mg/kg; i.p.) improved performance in the spatial object recognition test, the Y-maze task, and cued fear memory in mice (Lipina et al., 2013), raising the possibility that GSK3 inhibitors may play a role in future developments of cocktails of drugs that may be tested as cognitive enhancers.

3.3. Cognition in rodents after molecular modification of GSK3

Whereas administration of GSK3 inhibitors to healthy rodents generally has little effect on cognitive tasks, studies of mice expressing modified GSK3 have begun to provide more information about the influences of GSK3 on cognitive processes. Molecular reduction of GSK3 appears to be particularly detrimental for memory rather than learning. Heterozygote GSK3β knockout (GSK3β+/−) mice learned to find a fixed but hidden platform submerged in a pool in the Morris water maze equivalently to wild-type mice, but in later re-testing GSK3β+/−mice failed to locate the hidden platform, whereas it was easily located by wild-type mice (Kimura et al., 2008). In a contextual fear-conditioning test, GSK3β+/−Mice were not impaired in the ability to form and consolidate memory, but subsequent testing revealed impaired reconsolidation. This was further confirmed by the finding that GSK3 inhibition with AR-A014418 (30 mg/kg; i.p.) applied before the reconsolidation step significantly impaired memory reconsolidation, which was interpreted as a display of retrograde amnesia in mice deficient in GSK3β (Kimura et al., 2008). Mice lacking GSK3α demonstrated learning in the passive avoidance task equivalently to wild-type mice, but had an impaired ability to form and consolidate memory in a fear conditioning test (Kaidanovich-Beilin et al., 2009). These findings suggest that molecularly reducing GSK3 may have detrimental effects on memory, in contrast to the administration of GSK3 inhibitors. This detrimental effect may be due to the reduction of GSK3 during development in transgenic mice causing aberrations in the development of memory processes, or due to differences between molecular and pharmacological modifications of GSK3 in the extent or duration of reduction of each GSK3 isoform's activity. Thus, molecular reduction of GSK3 may not model well therapeutically applied drugs that inhibit GSK3.

The effects of excessive GSK3 activity also have been examined on cognition. Several studies investigated the effects of GSK3 overexpression, predominantly for modeling AD, and as discussed in section 4 these often found impaired cognition that was associated with ADlinked pathology and neuronal loss. Thus, this approach does not directly address potential regulatory actions of increased GSK3 activity that is not associated with neurodegeneration. Dewachter et al. (2009) took the less severe approach of studying GSK3β knockin mice, in which the inhibitory serine-9 of GSK3β was mutated to alanine to render GSK3β constitutively active and unable to be inhibited through the serine-9 phosphorylation mechanism. GSK3β knockin mice displayed impaired inhibitory avoidance learning and object recognition memory, but no deficits in cued and contextual fear conditioning tasks and conditioned taste aversion, and the mice were free of neurodegeneration (Dewachter et al., 2009). These findings suggest that loss of inhibitory control of GSK3 can result in impaired cognition, which may play a role in diseases and conditions exhibiting both activated GSK3 and cognition impairments.

3.4. Cognition in lithium-treated humans

It is unclear whether lithium alters cognition in healthy human subjects. Early reports of enhanced neurocognitive test performance after lithium treatment have been attributed to methodological limitations, such as practice-induced improvements (Dias et al., 2012). In contrast, several investigators reported that lithium causes transient and/or mild detrimental effects on several cognitive domains in healthy subjects, such as verbal learning and memory, without altering others, such as visual memory or attention (Weingartner et al., 1985; Linnoila et al., 1986; Stip et al., 2000; Wingo et al., 2009). On the other hand, a metaanalysis concluded that lithium seems not to impair cognition in healthy human subjects after administration for 2.5 weeks or longer (Wingo et al., 2009). Thus, therapeutic lithium levels appear not to improve cognition in healthy human subjects and may cause variable mild impairments in some individuals, whereas the effects of other GSK3 inhibitors have not been tested in healthy human subjects.

Altogether, the majority of studies indicate that administration of a moderate dose of lithium or another GSK3 inhibitor has no effect, or causes relatively minor impairments, on cognition in healthy rodents or humans. This stands in stark contrast to the significantly enhanced cognitive abilities provided by administration of GSK3 inhibitors in conditions associated with cognitive disabilities that are discussed in the following sections.

4. Effects of GSK3 inhibitors on cognition in Alzheimer's disease (AD) models

AD is a neurodegenerative disorder that culminates in neurodegeneration and severe impairments in cognition. AD neuropathology is characterized by extracellular plaques of aggregated amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles containing hyperphosphorylated tau, a microtubule-binding protein (Hardy et al., 1998). The Aβ hypothesis of the pathophysiology of AD posits that Aβ induces the formation of taucontaining neurofibrillary tangles and neuronal death, which contribute to progressively worsening cognitive abilities (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). GSK3 is intimately linked to AD neuropathology, as Aβ increases GSK3β activity (Takashima et al., 1996), GSK3 promotes the production of Aβ (Phiel et al., 2003), and GSK3 promotes apoptotic signaling induced by Aβ (reviewed in Mines et al., 2011). Furthermore, GSK3 phosphorylates tau and likely contributes to the hyperphosphorylation of tau in neurofibrillary tangles (Mandelkow et al., 1992; Hong et al., 1997; Muñoz-Montaño et al., 1997; Xie et al., 1998; Lovestone et al., 1999; Bhat et al., 2003). These findings suggest that GSK3 plays a central role in the pathophysiology of AD and have led many investigators to study the effects of GSK3 on cognition in rodent models of AD and in patients with AD (Martinez et al., 2011).

Genetically and pharmacologically increasing GSK3 activity have been used to model events that may occur in AD, manipulations that exacerbate cognitive impairments and neuropathology in rodent models of AD. Conditional overexpression of GSK3β in mouse cortical and hippocampal neurons resulted in impaired performance in the Morris water maze, hyperphosphorylation of tau, reactive astrocytosis and microgliosis, and neuronal death (Lucas et al., 2001; Hernandez et al., 2002). Suppression of overexpressed GSK3β reversed the spatial memory deficit in the novel object recognition task, reduced tau hyperphosphorylation, and decreased reactive gliosis and neuronal death (Engel et al., 2006). Deletion of tau expression in GSK3β-overexpressing mice significantly reduced impairment in the Morris water maze, indicating that GSK3-mediated tau phosphorylation contributed to this cognitive impairment (Gómez de Barreda et al., 2010). The GSK3-tau interaction was further implicated by cognitive impairments in GSK3β x Tau-P301L mice with increased GSK3β expression and expression of tauopathy-associated mutated tau. These mice displayed impaired novel object recognition memory and passive avoidance learning, which occurred prior to the deposition of tau aggregates, suggesting that early tau pathology due to increased GSK3β activity may cause synaptic deficits that underlie the cognitive impairments in the GSK3β x Tau-P301L mice (Terwel et al., 2008).

Activation of GSK3 also has been reported to be detrimental for cognitive tasks in studies of potential pathological mechanisms in AD. Intracerebroventricular infusion of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin and the protein kinase C inhibitor GF-109203X in adult rats caused spatial memory deficits in the Morris water maze and hyperphosphorylation of tau (Liu et al., 2003). Induction of diabetes by streptozotocin treatment in human amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice increased GSK3β activity and impaired performance in the Barnes circular maze task (Jolivalt et al., 2010). Increased GSK3 activity in rats following expression of the C-terminal fragment of protein phosphatase 2A, which can dephosphorylate the inhibitory serine in GSK3, impaired performance in the Morris water maze, increased Aβ levels, and caused hyperphosphorylation of tau (Wang et al., 2010). Although all of these interventions can be expected to have multiple effects, they add to the correlative evidence between activation of GSK3 and worsened pathology and cognitive abilities. Altogether, a variety of molecular and pharmacological approaches suggest that increased GSK3 activity likely contributes to pathology and cognitive impairments in rodent models of AD.

Further evidence implicating actions of GSK3 in cognitive impairments in rodent models of AD has come from studies showing that administration of the GSK3 inhibitor lithium reduces neuropathology and cognitive deficits. Lithium (2 mEq/kg; i.p.) administered to rats daily for 2 weeks prior, and 2 weeks following, intrahippocampal infusion of Aβ fibrils blocked spatial memory deficits in the Morris water maze (De Ferrari et al., 2003). Treatment with lithium (200 mM; icv) in adult male rats reversed the spatial memory impairment in the Morris water maze and abolished hyperphosphorylation of tau caused by activation of GSK3 (Liu et al., 2003). Lithium treatment (20 mg/kg; i.p.) daily for 3 months improved impaired learning in the Morris water maze in human APP transgenic mice, which was associated with decreased Aβ levels and reduced tau phosphorylation (Rockenstein et al., 2007). Dietary chronic lithium treatment for 4 weeks ameliorated a working memory deficit in the Y-maze paradigm in aged APP-intracellular domain-overexpressing transgenic mice (Ghosal et al., 2009). Lithium treatment (3 mEq/kg; i.p.) daily for 12 weeks in aged transgenic mice expressing mutated APP and presenilin-1 ameliorated deficits in the Morris water maze and reduced Aβ plaques and inflammation (Toledo and Inestrosa, 2010). Chronic lithium treatment in the food for 5 weeks in hemizygous TgCRND8 mice that develop amyloid deposition at 3 months of age attenuated cognitive deficits in the step down inhibitory avoidance test and the Morris water maze (Fiorentini et al., 2010). Chronic dietary lithium treatment for 6 weeks protected aged 3xTg-AD mice from lipopolysaccharide-induced impairment in the Morris water maze (Sy et al., 2011). These reports demonstrate that treatment with lithium can rescue a variety of cognitive impairments in rodent models of AD if treatment is initiated early in the pathological process, but not all studies found improvements after lithium treatment. Dietary chronic lithium treatment begun at 6 months of age in TgCRND8 mice (after amyloid deposition) did not improve cognition in the step down inhibitory avoidance test or the Morris water maze, although the number and size of Aβ plaques was significantly reduced (Fiorentini et al., 2010). In aged 3xTg-AD mice, daily lithium treatment (300 µl of 0.6mol/L; i.p.) for 4 weeks did not rescue deficits in working memory in the T-maze paradigm (Caccamo et al., 2007). In APPwDI/NOS2−/− mice, chronic dietary lithium treatment for 8 months did not rescue memory in the radial-arm maze (Sudduth et al., 2012). Thus, lithium treatment appears most effective in improving cognitive abilities in rodent models of AD when treatment began before major pathologies were established.

In addition to lithium, newer small molecule inhibitors of GSK3 have been found to rescue cognitive deficits in several rodent models of AD. Treatment with the GSK3 inhibitor NP12 (200 mg/kg; oral gavage) daily for 3 months in aged double APP-tau transgenic mice diminished deficits in the Morris water maze, and decreased tau phosphorylation and amyloid deposition (Serenó et al., 2009). Aβ-induced deficits in the Morris water maze were ameliorated by chronic administration of the GSK3 inhibitor SB216763 (78 pmol/day; icv), which also reduced tau phosphorylation and neurodegeneration (Hu et al., 2009). APP/Presenilin-1 double transgenic mice treated with the GSK3 inhibitor indirubin-3'-monoxime (20 mg/kg; i.p.) 3 times per week for 8 weeks exhibited reduced impairments in the Morris water maze, which correlated with attenuation of Aβ production and tau hyperphosphorylation (Ding et al., 2010). In 3XTg-AD mice, treatment with the GSK3 inhibitor MMBO (1 or 3 mg/kg; orally) for 25 days attenuated impairments in the Y-maze task and the novel object recognition test and decreased tau phosphorylation (Onishi et al., 2011). Treatment with the GSK3 inhibitor AR-A014418 (5 mg/kg; i.p.) daily for 4 weeks alleviated deficits in the Morris water maze in APP23/PS45 double transgenic mice, which was accompanied by reduced Aβ deposition and neuritic plaques (Ly et al., 2013). Transgenic mice that co-express AD mutations in APP and presenilin-1 (5XFAD mice) treated with the selective, substrate-competitive GSK3 inhibitor L803-mts (80 µg; intranasally) every other day for 120 days exhibited enhanced cognition in the contextual fear conditioning test, which was associated with decreased Aβ (Avrahami et al., 2013). Thus, administration of GSK3 inhibitors can ameliorate cognitive impairments in a number of mouse models of AD.

Inhibiting GSK3 using genetic approaches to specifically knockdown either GSK3α or GSK3β can also ameliorate cognitive impairments in AD mouse models. Genetically inactivating GSK3β by crossing human APP transgenic AD mice with dominant-negative GSK3β transgenic mice improved learning in the Morris water maze, reduced Aβ load and decreased tau phosphorylation in the double transgenic mice compared to human APP mice (Rockenstein et al., 2007). Reduced expression of GSK3α in PDAPP (+/−) transgenic mice attenuated deficits in the Barnes maze (Hurtado et al., 2012). Thus pharmacological or genetic approaches to selectively inhibit GSK3 appear to rescue cognitive impairments and attenuate neuropathology occurring in AD in rodent models.

The capacity of GSK3 inhibitors to alleviate symptoms of AD in mouse models has led to several studies in human patients. These studies indicate that lithium treatment protects patients with bipolar disorder from developing AD and increases measures of cognition in patients with AD and dementia or mild cognitive impairment. For example, elderly patients with bipolar disorder (mean age 68.2 years) that had been treated continuously with lithium had reduced prevalence of AD compared to the general elderly population (Nunes et al., 2007). Additionally, bipolar patients continuously treated with lithium exhibited a reduced rate of dementia compared to bipolar patients treated with anticonvulsants, antidepressants or antipsychotics (Kessing et al., 2010). In a randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group multicenter 10 week study, patients with early AD treated with lithium had a significant decrease in Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale scores, indicating improved cognitive function, and as the lithium serum concentration increased, cognitive impairment decreased in individuals with early AD (Leyhe et al., 2009). Patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment who received lithium for 12 months also performed better on the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale and in attention tasks compared to amnestic patients that did not receive lithium (Forlenza et al., 2011). In a placebo-controlled trial, long-term lithium treatment slowed the progression of cognitive and functional deficits in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (Forlenza et al., 2012). Patients with dementia that were currently taking, or had taken, lithium for 48.4 ± 51.8 months performed better on the Mini-mental State Examination than patients who had never taken lithium (Terao et al., 2006). AD patients treated with lithium for 15 months performed better than untreated AD patients on the Mini-mental State Examination, and significant differences between lithium-treated and untreated AD patients began 3 months after the start of treatment and increased progressively (Nunes et al., 2013). However, significant cognitive improvement on the Mini-mental State Examination was not found in elderly individuals with mild to moderate AD treated with lithium for up to one year (Macdonald et al., 2008), and lithium treatment for 6 weeks did not improve cognition in a pilot study of AD patients (Pomara, 2009). Promising results with lithium contributed to the development of a phase II pilot study of the GSK3 inhibitor Tideglusib in patients with mild to moderate AD. This study established the safety and tolerability of this GSK3 inhibitor, and although there were trends towards improvement, further trials will be required to determine if cognitive impairments in AD are significantly improved (del Ser et al., 2013).

Altogether, although cognitive enhancement in animal models of AD is clearly evident following treatment with lithium or other GSK3 inhibitors, further studies will be needed, particularly including treatment that begins early in the disease, to determine if cognitive decline in patients with AD can be slowed by GSK3 inhibitors.

5. Effects of GSK3 inhibitors on cognition in Fragile X syndrome

Fragile X syndrome is the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability. Fragile X syndrome is caused by a trinucleotide repeat expansion in the X chromosome that silences the Fragile X Mental Retardation 1 gene, suppressing expression of Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (Pieretti et al., 1991; Verkerk et al., 1991; Mines and Jope, 2011). The Fragile X (FX) mouse model lacks expression of Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein and displays many characteristics of Fragile X syndrome, including cognitive impairments, locomotor hyperactivity, social interaction deficits, increased audiogenic seizure susceptibility, and autistic-like behaviors, among others (Bakker et al., 1994; Kooy, 2003).

There have been several reports demonstrating that inhibition of GSK3 improves impaired cognition in FX mice. The first of these demonstrated that chronic dietary lithium treatment for three weeks reversed a learning deficit in adult male FX mice in the passive avoidance task (Yuskaitis et al., 2010), as did chronic dietary lithium treatment that began at weaning (3 weeks old) and was continued to the ages of 8–11 weeks (Liu et al., 2011). Chronic dietary lithium treatment that began in adolescence (4 weeks old) and was continued for 8 weeks, or 4 weeks of dietary lithium treatment in adult FX mice, reversed deficits in FX mice in the visual object novelty detection task and temporal ordering for visual objects task, and improved spatial learning in the coordinate and categorical processing tasks (King and Jope, 2013). In a small open-label trial of lithium treatment in children and young adults with Fragile X syndrome, lithium treatment significantly improved cognition in the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status List Learning measure (Berry-Kravis et al., 2008). Thus, lithium administration to FX mice at a variety of ages improves cognitive abilities in several tasks, and preliminary evidence indicates that lithium also may be effective in patients.

Similar cognitive enhancing effects of other specific inhibitors of GSK3 indicate that the beneficial effects of lithium in FX mice likely result from its inhibition of GSK3. Chronic treatment of adult FX mice with the GSK3 inhibitor SB216763 (2 mg/kg; i.p.) every other day for 2 weeks improved performance in the contextual and tone trace conditioning tests and enhanced spatial learning in the delayed non-matching-to-place radial arm maze (Guo et al., 2012). Acute treatment of FX mice with the specific GSK3 inhibitors TDZD-8 (5 mg/kg; i.p.) or VP0.7 (5 mg/kg; i.p.) reversed impairments in visual object novelty detection task, temporal ordering for visual objects task, and spatial learning in the coordinate and categorical processing tasks (Franklin et al., 2013). Altogether, GSK3 inhibitors have provided more cognitive benefits in FX mice, as well as in humans with Fragile X syndrome, than any other therapeutic intervention.

6. Effects of GSK3 inhibitors on cognition in other diseases and disease models

6.1 Down syndrome

Down syndrome, caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21, is associated with intellectual disabilities that include language, verbal and spatial learning, and memory. The trisomic Ts65Dn mouse model re-capitulates some of the impaired cognitive abilities characteristic of Down syndrome (Reeves et al., 1995). Four weeks of lithium treatment in the food normalized impaired behavior of Ts65Dn mice in contextual fear conditioning, spatial memory, and novel object recognition tasks, changes that were associated with lithium-induced recovery of impairments in dentate gyrus LTP and neurogenesis (Contestabile et al., 2013).

6.2. Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive degeneration of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons that causes memory impairments, sleep abnormalities, anxiety, depression, bradykinesia, tremor, and muscular rigidity (Dawson and Dawson, 2003; Chaudhuri et al., 2006). Administration of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MTPT) is widely used to model Parkinson's disease in rodents (Schober, 2004). Lithium treatment (47.5 mg/kg, i.p.) for seven days prior to a single bilateral intranasal administration of MPTP attenuated deficits in olfactory discrimination, social recognition, and short-term inhibitory avoidance memory impairment evaluated in the step-down inhibitory avoidance task induced by MPTP in Wistar rats, improvements that were associated with less striatal dopamine depletion in lithium-treated rats (Castro et al., 2012).

6.3. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1)

SCA1 is a dominantly inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by excess CAG repeats in the ataxin 1 gene, and is characterized by progressive loss of motor control and cognitive impairments (Watase et al., 2007). Sca1(1544Q/2Q) mice, a knockin mouse model created by targeting 154 CAG repeats into the endogenous mouse locus, display many features of human SCA1, including cognitive deficits, loss of motor coordination, premature death, Purkinje cell loss, and age-related hippocampal synaptic dysfunction (Watase et al., 2002). Chronic dietary lithium treatment ameliorated cognitive deficits in adult Sca1(1544Q/2Q) mice in the Morris water maze test and in contextual fear conditioning, whereas lithium treatment did not improve impaired cued fear conditioning, indicating that lithium treatment protects hippocampus-dependent cognitive functions in Sca1(1544Q/2Q) mice (Watase et al., 2007).

6.4. Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

TBI results from direct damage to the brain that causes many pathological effects that can continue to evolve over time, including changes in neuronal architecture and death, which contribute to learning and memory deficits (Dixon et al., 1991; Thompson et al., 2005; Blennow et al., 2012). Lithium pretreatment (1 mmol/kg; i.p.) for 2 weeks protected adult mice against TBI-induced impairments in the Morris water maze task, which was accompanied by attenuated neuronal degeneration (Zhu et al., 2010). Post-injury treatment with lithium (1 mEq/kg; s.c.) also improved performance in the Morris water maze that was accompanied by reduced hippocampal CA3 neuron loss (Dash et al., 2011). Following experimental TBI, rats treated with lithium (1 mEq/kg; s.c.) for two weeks displayed improved hippocampal-dependent short term and long term spatial memory for platform location and quadrant preference in the Morris water maze, and daily treatment with the GSK3 inhibitor SB216763 (5 mg/kg; i.p.) for 5 days improved short term, but not long term, spatial memory (Dash et al., 2011). Post-TBI treatment with lithium (1.5 mEq/kg; i.p.) for up to 3 weeks also attenuated TBI-induced deficits in the Morris water maze and increased hippocampal-dependent learning and memory in the Y-maze test measured 10 days post-injury, which was associated with attenuated pathological markers (Yu et al., 2012).

6.5. Ischemic stroke

Ischemic stroke survivors exhibit impairments in cognition, sensation, perception and movement (Carmichael, 2003), and lithium reduces ischemia-induced neuronal damage in rodents (Nonaka and Chuang, 1998). Treatment of adult male rats with lithium (1 mmol/kg; i.p.) for 2 weeks prior to, and 9 days after, transient brain ischemia attenuated deficits in performance in the Morris water maze, which was associated with decreased ischemia-induced neuronal death (Yan et al., 2007).

6.6. HIV encephalitis

HIV patients with excessive neuroinflammation often exhibit severe cognitive deficits (Cherner et al., 2002). There is much interest in the potential therapeutic use of GSK3 inhibitors in HIV patients because of their neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory actions (Dewhurst et al., 2007; Crews et al., 2009). For example, 14 days of lithium treatment (2 mg/kg; i.p.) in 4 month old HIV-gp-120 transgenic mice provided protection from gp120-mediated hippocampal toxicity and reduced dendritic damage (Everall et al., 2002). The first pilot study in fifteen cognitively impaired HIV patients found that 10 weeks of lithium treatment did not improve cognitive performance (The Dana Consortium, 1996). However, a subsequent study in eight patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment found that lithium treatment for 12 weeks improved cognitive performance in all patients and cognitive impairment was eliminated in six patients (Letendre et al., 2006). Another study in eleven patients demonstrated that lithium treatment for 10 weeks did not improve cognition, but imaging indicated that lithium reduced CNS injury (Schifitto et al., 2009). Thus, although lithium clearly is neuroprotective, further studies appear warranted to clarify if GSK3 inhibitors reduce cognitive impairments in patients with HIV encephalitis.

6.7. Cerebral malaria

Cerebral malaria results from infection with Plasmodium falciparum and causes long-term cognitive impairments even in survivors with successful eradication of the parasite (Falchook et al., 2003; Boivin et al., 2007). Dai et al (2012) found that experimental cerebral malaria induced in mice caused significant hemorrhage in brain regions, cognitive impairment, and activation of GSK3 after eight days. Lithium treatment (20 mg/kg; i.p.) for 10 days in conjunction with chloroquine administration normalized cognitive deficits in infected mice in the object location test, suggesting that lithium may ameliorate some of the long-term neurological deficits associated with cerebral malaria (Dai et al., 2012).

6.8. Diabetes

People with diabetes have a higher rate of impaired learning, memory, and mental flexibility, and are at a higher risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease than the general population, and learning deficits also occur in insulin-deficient mice. Insulin-deficient diabetes induced in rats by streptozotocin caused long-term memory deficits in the autoshaping learning task that were reversed by treatment with lithium given after the training task (Ponce-Lopez et al., 2011). Insulin-deficient diabetes induced in mice by treatment with streptozotocin impaired performances in the Barnes maze and the object recognition task that were attenuated by treatment with the GSK3 inhibitor AR-A014418 (30 µmol/kg; i.p.) (King et al., 2013). These results suggest that GSK3 inhibition may be useful for attenuating diabetes-associated cognitive deficits.

6.9. Postoperative cognition dysfunction

Postoperative cognition dysfunction, characterized by impairment of recent memory, concentration, language comprehension, and social integration, occurs in over 60% of older patients following surgery and anesthesia and can persist for weeks or months after surgery (Hovens et al., 2012). Treatment of 18 month old male rats with lithium (2 mmole/kg; i.p.) for seven days prior to exploratory laparotomy attenuated surgery-induced impaired performance in the Morris water maze (Zhao et al., 2011).

7. GSK3 inhibitors can improve treatment-induced cognitive impairments

GSK3 inhibition has been found to reduce cognitive impairments that were induced in rodents by several different treatments. Cranial irradiation therapy is a common treatment for brain tumors, and although cancer cure rates are improved, learning disorders and memory deficits commonly occur following treatment in children and adults (Roman and Sperduto, 1995). Pretreatment of mouse pups with lithium (40 mg/kg; i.p.) for one week prior to cranial irradiation improved performance in the Morris water maze task tested six weeks after irradiation (Yazlovitskaya et al., 2006). Similarly, pretreatment with the GSK3 inhibitors SB216763 (0.6 mg/kg; i.p.) or SB415286 (1 mg/kg; i.p.) for 3 days before cranial irradiation improved Morris water maze performance in irradiated mice (Thotala et al., 2008). In addition, Khasraw et al (2012) noted that lithium treatment reduces radiation-induced gliosis that can contribute to decreased neurogenesis and cognitive deficits. A phase I clinical trial in which five cancer patients were treated with lithium one week before cranial irradiation showed no decline in short term memory of these patients in global and spatial memory test (Yang et al., 2007).

In addition to cranial radiation, GSK3 inhibitors also provided protection from cognitive impairments induced by a variety of other treatments. Chronic lithium treatment (5.0 to 7.5 mEq/kg; orally; 3 times/day) of 8 rhesus monkeys between the ages of 13 and 30 years restored working memory on the delayed response task after impairment induced by cirazoline treatment, an adrenergic receptor agonist (Birnbaum et al., 2004). Chronic stress impaired spatial memory in the Morris water maze task in rats, and this was prevented by four weeks of lithium treatment in the food (Vasconcellos et al., 2003; de Vasconcellos et al., 2005). Infusion of the protein kinase A inhibitor H-89 into the hippocampal CA1 region of rats impaired spatial memory retention in the Morris water maze task, which was prevented by four weeks of pretreatment with lithium (600 mg/L in the drinking water) (Sharifzadeh et al., 2007). Administration of the anesthetic sevoflurane to rats activated GSK3 and impaired memory consolidation, both of which were reversed by acute lithium treatment (100 mg/kg; i.p.) (Liu et al., 2010). Deficits in an autoshaping learning task induced in male rats by intracerebroventricular infusion of streptozotocin for 2 weeks were reversed by acute treatment with lithium (100 mg/kg; i.p.) (Ponce-Lopez et al., 2011). Intracerebroventricular infusion of angiotensin II to rats increased GSK3β activity and induced deficits in the Morris water maze, which was reversed by treatment with the GSK3 inhibitor SB216763 (20 ng/µl; icv) (Tian et al., 2012). Memory impairment in the contextual fear conditioning task induced by administration to mice of MK-801, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, was reversed by treatment twice daily for 3 days with the GSK3 inhibitor AZD1080 (4 or 15 µmol/kg; oral gavage) (Georgievska et al., 2013). Lithium treatment (1 or 4 ml/kg of 0.15 M lithium) also attenuated ouabain-induced impairments in the Morris water maze (Wang et al., 2013). Adult offspring of poly(I:C)-exposed mothers, an infection-based mouse model of neuropsychiatric disease, displayed deficits in the spontaneous alternation in the Y-maze cognitive task that were alleviated by acute administration of the GSK3 inhibitor TDZD-8 (1 or 10 mg/kg; i.p.) (Willi et al., 2013). The diversity of chemicals and treatments used to induce cognitive deficits that were ameliorated by GSK3 inhibitors indicates that protection was unlikely due to blocking the action of the insult, but more likely due to protection of a fundamental component of the cognitive process.

8. Effects of lithium treatment on cognition in patients with bipolar disorder

Lithium was the first mood stabilizer used to successfully treat bipolar disorder, previously known as manic-depression, and much evidence indicates that inhibition of GSK3 by lithium is an important component of its therapeutic action (Jope, 2011). Although previously often overlooked, it is now recognized that significant cognitive deficits are associated with bipolar disorder, such as impairments in verbal memory, processing speed, and attention, and that these can persist even during clinical remission (Clark et al., 2002; Martinez-Aran et al., 2004). Furthermore, several studies have concluded that bipolar disorder patients exhibit cognitive impairments in all phases of the disorder and that these are a fundamental characteristic of bipolar disorder, not a consequence of medications (Smigan and Perris, 1983; Engelsmann et al., 1988; Robinson and Ferrier, 2006; Mur et al., 2008; Lopez-Jaramillo et al., 2010).

Since lithium is the classical mood stabilizer, many investigators have examined its effects on cognition in bipolar disorder patients, but results have been contradictory and the issue remains unsettled (Balanza-Martinez et al., 2010; Dias et al., 2012). Many studies concluded that cognitive abilities of lithium-treated bipolar disorder patients did not differ from those free of medication (Marusarz et al., 1981; Lund et al., 1982; Smigan and Perris, 1983; Engelsmann et al., 1988; Joffe et al.,1988; Sharma and Singh, 1988; Jauhar et al., 1993; Van Gorp et al., 1998; El-Badri et al., 2001; Clark et al., 2002; Altshuler et al., 2004; Mur et al., 2008; Lopez-Jaramillo et al., 2010; Arts et al., 2011). On the other hand, several studies found that lithium has a mild negative effect on cognition in bipolar disorder patients. Cognitive domains that have been reported to be worsened after lithium treatment of bipolar disorder patients include verbal learning and memory, attention, and short-term memory (Christodoulou et al., 1981; Elssas et al., 1981; Loo et al., 1981; Shaw et al., 1987; Hatcher et al., 1990; Honig et al., 1999; Pachet and Wisniewski, 2003; Wingo et al., 2009). However, there are also reports of no lithium-induced impairments of visuospatial skills, visual memory, delayed verbal memory, attention, and executive performance (Honig et al., 1999; Pachet and Wisniewski, 2003, Wingo et al., 2009). A review of the effects of lithium in bipolar disorder patients concluded that there were five consistent findings: "impairment on tasks of psychomotor speed, impaired functioning in the majority of studies examining verbal memory, no impairment on tasks of visuospatial constructional ability or attention/ concentration, and no negative cumulative effect" (Pachet and Wisniewski, 2003). A meta-analysis concluded that in bipolar disorder patients "lithium treatment appears to have only few and minor negative effects on cognition" (Wingo et al., 2009). These investigators also pointed out that in many studies there have been methodological and statistical limitations, non-homogeneous patient populations, diverse research designs, varied diagnostic methods, and a number of uncontrolled variables (Pachet and Wisniewski, 2003; Wingo et al., 2009; Balanza-Martinez et al., 2010; Dias et al., 2012). Altogether, the effect of lithium on cognitive dysfunction in bipolar disorder patients remains unresolved, but it is evidently not beneficial for the cognitive facet of bipolar disorder and may be moderately detrimental for specific functions, but a conclusive resolution will require further well-designed studies. Thus, despite the many conditions in which lithium improves cognitive performance reviewed here, it is rather ironical that lithium does not do so in bipolar disorder, the preeminent condition that lithium has proven therapeutic efficacy on the defining characteristic of the disorder.

9. Mechanisms underlying improved cognition following GSK3 inhibition

Multiple mechanisms appear to contribute to the cognition-protecting actions of GSK3 inhibitors, several of which include the following.

9.1. Long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD)

The most direct mechanisms known by which GSK3 may regulate cognitive functions are by influencing the processes of LTP and LTD (Bradley et al., 2012). LTP and LTD are components of synaptic plasticity that are thought to be critical regulators of learning and memory, and GSK3 is intimately involved in both processes. LTP increases the inhibitory serine-phosphorylation of GSK3 and overexpression or activation of GSK3 impairs LTP (Hooper et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2007). These findings indicate that GSK3 has to be inactivated for optimal establishment of LTP, raising the possibility that pathologically active GSK3 may impair LTP in conditions associated with impaired cognition. In contrast, LTD increases GSK3 activity and inhibition of GSK3 prevents the induction of LTD, demonstrating that active GSK3 supports the induction of LTD (Peineau et al., 2007). Thus, inhibition of GSK3 facilitates LTP, but GSK3 activity is required for LTD, indicating that lithium and other GSK3 inhibitors may prevent impairments in LTP and reduce the induction of LTD. Support for this relationship comes from studies demonstrating that the rescue of abnormal LTP and/or LTD following treatment with GSK3 inhibitors is accompanied by increased cognition in mouse models of Fragile X syndrome (Choi et al., 2011; Franklin et al., 2013), AD (Ma et al., 2010; Li et al., 2012), and Down syndrome (Contestabile et al., 2013). These studies indicate that GSK3 inhibition may improve learning and memory impairments in some conditions by regulating hippocampal synaptic plasticity.

9.2. Neurogenesis

Part of the improvement in cognition provided by administration of GSK3 inhibitors in rodent models of diseases with impaired cognition may be due to increased neurogenesis. The discovery that new neurons are generated in the adult hippocampus led to an explosion of studies to identify the functional consequences of neurogenesis, and to determine if impaired neurogenesis contributes to CNS diseases and is bolstered by therapeutic drugs (Lie et al., 2004). Neurogenesis appears to support certain forms of learning and memory and may be defective in some conditions associated with impairments in cognition (van Praag et al., 2005; Leuner et al., 2006; Deng et al., 2010; Massa et al., 2011). Evidence indicates that dysregulated GSK3 may contribute to deficient neurogenesis in some conditions because neurogenesis is impaired by constitutively active GSK3 in mice (Eom and Jope, 2009), and molecular deletion of GSK3 in mouse neural progenitors increased neurogenesis (Kim et al., 2009). Thus, in diseases such as depression, Fragile X syndrome, and Alzheimer's disease in which GSK3 in the CNS is abnormally active, an outcome may be diminished neurogenesis and consequently cognitive impairments. Conversely, neurogenesis is increased by treatment with lithium or other drugs that inhibit GSK3 (Chen et al., 2000: Hashimoto et al., 2003; Silva et al., 2008; Wexler et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009; Morales-Garcia et al., 2012), and treatment with the GSK3 inhibitor SB216763 (2 mg/kg; i.p.) every other day for 2 weeks increased neurogenesis that is impaired in mice expressing DISC1 mutations (Mao et al., 2009). Thus, administration of GSK3 inhibitors may improve cognition in part by restoring impairments in neurogenesis. This relationship has been supported by studies reporting increased neurogenesis following administration of GSK3 inhibitors that was correlated with improved cognition in mouse models of Fragile X syndrome (Guo et al., 2012), Down syndrome (Contestabile et al., 2013), and AD (Serenó et al., 2009; Fiorentini et al., 2010; Jo et al., 2011).

9.3. Inflammation

GSK3 inhibitors may improve deficient cognitive functions in part by their anti-inflammatory effects. Many CNS diseases are accompanied by neuroinflammation, which often exacerbates impaired neuronal function and survival. One critical outcome of neuroinflammation is the impairment of a broad range of cognitive functions (Streck et al., 2008). Since GSK3 was first identified as an important promoter of inflammatory responses in peripheral cells (Martin et al., 2005), an equivalent role for GSK3 has been established in the CNS (Beurel, 2011). Thus, GSK3 inhibitors diminish many inflammatory responses by both astrocytes and microglia in the CNS, as well as by peripheral immune cells, reducing inflammation in the CNS (Beurel and Jope, 2009; Cheng et al., 2009; Yuskaitis and Jope, 2009). Transcription factors represent a key group of targets by which GSK3 inhibitors reduce inflammation, including suppressing promoters of inflammation such as transcription factors in the STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) family and NF-κB, and amplifying anti-inflammatory actions of the transcription factor CREB (cyclic AMP response element binding protein) (Martin et al., 2005; Beurel and Jope, 2008). Anti-inflammatory actions of GSK3 inhibitors are sufficient to profoundly diminish diseases in which inflammation has a major impact, such as sepsis and the mouse model of multiple sclerosis (Martin et al., 2005; De Sarno et al., 2008; Beurel et al., 2011; Beurel et al., 2013). Inflammation is well-known to accompany and exacerbate neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD, and neuroinflammation is also now recognized as an important component of the disease process in psychiatric diseases, such as depression (Raison and Miller, 2013) and schizophrenia (Mansur et al., 2012). Thus, by reducing inflammation, GSK3 inhibitors may improve cognitive functions otherwise damaged by inflammatory molecules in many neurological and psychiatric diseases involving neuroinflammation, such as ischemia, traumatic brain injury and AD.

9.4. Neuroprotection

One of the most notorious actions of dysregulated GSK3 is its promotion of apoptosis, an outcome thought to frequently contribute to neurological diseases (Beurel and Jope, 2006). It appears that GSK3 promotes the intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway following exposure to apparently any insult capable of inducing this response. Reciprocally, the ability of GSK3 inhibitors to reduce apoptosis is an important part of their well-recognized characteristic as neuroprotective agents. This neuroprotective capacity may underlie several of the reported cognition-protective effects of GSK3 inhibitors discussed above, particularly in neurodegenerative diseases. For example, GSK3 can promote apoptosis in conditions modeling AD (Mines et al., 2011) and Parkinson's disease (King et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2004). Thus, administration of GSK3 inhibitors may diminish cognition impairments in some conditions by reducing apoptotic loss of neurons rather than by a direct effect on cognitive mechanisms.

In addition to apoptosis, GSK3 inhibitors also provide neuroprotective resilience by a number of mechanisms, such as reducing neuronal dysfunction resulting from endoplasmic reticulum stress (Song et al., 2002; Meares et al., 2011) and oxidative stress (Schäfer et al., 2004; King and Jope, 2005), and by promoting the production of intracellular chaperone proteins (Chu et al., 1996; Bijur and Jope, 2000). Besides being implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, these conditions associated with impaired neuronal function have been linked to many psychiatric and neurological diseases (Bown et al., 2000; Lin and Beal, 2006; Andreazza et al., 2010; Roussel et al., 2013). Thus, bolstering neuronal resilience, as well as reducing apoptosis, may contribute to the capacity of GSK3 inhibitors to reduce disease-associated impairments in cognition.

10. Conclusions

Impairment of cognition is a devastating outcome of many conditions affecting the CNS. In a remarkable number and broad spectrum of conditions that cause cognitive impairments in rodents, inhibition of GSK3 protects cognitive processes or promotes their repair (Figure 1). One limitation of the reported pharmacological intervention studies is that the majority have relied on lithium, and have not compared its effects with other GSK3 inhibitors. Thus there is a great need for cognition studies using other GSK3 inhibitors, as well as for further studies of rodents with molecular modifications of GSK3, to verify that GSK3 is the therapeutic target protecting cognitive processes, and to provide alternatives to lithium for therapeutic interventions. The current state of research is also limited by the relatively small number of different GSK3 inhibitors that have been tested in cognition studies, which is surprising because many GSK3 inhibitors have been developed during the last decade (Eldar-Finkelman and Martinez, 2011). Additionally, little information is available from comparative studies using several GSK3 inhibitors in cognition studies, or in studies of the duration of their effectiveness. Thus, the reviewed studies have provided strong initial evidence that GSK3 inhibitors have the potential to ameliorate cognitive impairments, but further studies are needed to identify the most efficacious drugs and those that are effective during prolonged administration. Furthermore, we should emphasize that there is likely significant overlap in behaviors that are commonly labeled as being related to cognition, depression, mania, anxiety, and others, so that drug effects on one may certainly affect others. Additionally, clarification of the mechanisms underlying the cognitive enhancing actions of GSK3 inhibitors in each condition would provide a better understanding of the causes of cognitive decline and of the mechanisms that may be exploited in the development of improved interventions. It is unlikely that a single mechanism accounts for all of the reported cognition-protecting effects of GSK3 inhibitors. We have discussed four mechanisms that are likely to play a role in different conditions, but this short list does not exclude additional mechanisms of action. Most importantly, considering the prevalence and devastating consequences of loss of cognitive functions, and the dearth of efficacious interventions, the findings summarized here emphasize the importance of greater development and utilization of GSK3 inhibitors to treat conditions causing cognitive impairments.

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors' laboratories was supported by grants from the NIMH (MH038752, MH090236, MH095380)

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid-β peptide

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- CNS

central nervous system

- FX

Fragile X

- GSK3

glycogen synthase kinase-3

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MTPT

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- SCA1

spinocerebellar ataxia type 1

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andreazza AC, Shao L, Wang JF, Young LT. Mitochondrial complex I activity and oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins in the prefrontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:360–368. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler LL, Ventura J, van Gorp WG, Green MF, Theberge DC, Mintz J. Neurocognitive function in clinically stable men with bipolar I disorder or schizophrenia and normal control subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts B, Jabben N, Krabbendam L, van Os J. A 2-year naturalistic study on cognitive functioning in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:190–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrahami L, Farfara D, Shaham-Kol M, Vassar R, Frenkel D, Eldar-Finkelman H. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 ameliorates β-amyloid pathology and restores lysosomal acidification and mammalian target of rapamycin activity in the Alzheimer disease mouse model: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1295–1306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain J, Plater L, Elliott M, Shpiro N, Hastie CJ, McLauchlan H, et al. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. Biochem J. 2007;408:297–315. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker CE, Dutch-Belgian Fragile X Consortium et al. Fmr1 knockout mice: a model to study fragile X mental retardation. Cell. 1994;78:23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balanzá-Martínez V, Selva G, Martínez-Arán A, Prickaerts J, Salazar J, González-Pinto A, et al. Neurocognition in bipolar disorders--a closer look at comorbidities and medications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;626:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry-Kravis E, Sumis A, Hervey C, Nelson M, Porges SW, Weng N, et al. Open-label treatment trial of lithium to target the underlying defect in fragile X syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29:293–302. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31817dc447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E. Regulation by glycogen synthase kinase-3 of inflammation and T cells in CNS diseases. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:18. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Jope RS. The paradoxical pro- and anti-apoptotic actions of GSK3 in the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathways. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;79:173–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Jope RS. Differential regulation of STAT family members by glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21934–21944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802481200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Jope RS. Lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-6 production is controlled by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and STAT3 in the brain. J Neuroinflammation. 2009;11:6–9. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Yeh WI, Michalek SM, Harrington LE, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is an early determinant in the differentiation of pathogenic Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:1391–1398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Yeh WI, Song L, Palomo V, Michalek SM, et al. Regulation of Th1 cells and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) by glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Immunol. 2013;190:5000–5011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat R, Xue Y, Berg S, Hellberg S, Ormö M, Nilsson Y, et al. Structural insights and biological effects of glycogen synthase kinase 3-specific inhibitor ARA014418. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45937–45945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijur GN, Jope RS. Opposing actions of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and glycogen synthase kinase-3β in the regulation of HSF-1 activity. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2401–2408. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum SG, Yuan PX, Wang M, Vijayraghavan S, Bloom AK, Davis DJ, et al. Protein kinase C overactivity impairs prefrontal cortical regulation of working memory. Science. 2004;306:882–884. doi: 10.1126/science.1100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, Hardy J, Zetterberg H. The neuropathology and neurobiology of traumatic brain injury. Neuron. 2012;76:886–899. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin MJ, Bangirana P, Byarugaba J, Opoka RO, Idro R, Jurek AM, et al. Cognitive impairment after cerebral malaria in children: A prospective study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e360–e366. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bown C, Wang JF, MacQueen G, Young LT. Increased temporal cortex ER stress proteins in depressed subjects who died by suicide. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;22:327–232. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley CA, Peineau S, Taghibiglou C, Nicolas CS, Whitcomb DJ, Bortolotto ZA, et al. A pivotal role of GSK-3 in synaptic plasticity. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:13. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo A, Oddo S, Tran LX, LaFerla FM. Lithium reduces tau phosphorylation but not Aβ or working memory deficits in a transgenic model with both plaques and tangles. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1669–1675. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST. Plasticity of cortical projections after stroke. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1073858402239592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro AA, Ghisoni K, Latini A, Quevedo J, Tasca CI, Prediger RD. Lithium and valproate prevent olfactory discrimination and short-term memory impairments in the intranasal 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav Brain Res. 2012;229:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH, National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006;11:1116–1125. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Rajkowska G, Du F, Seraji-Bozorgzad N, Manji HK. Enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis by lithium. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1729–1734. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Bower KA, Ma C, Fang S, Thiele CJ, Luo J. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) mediates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neuronal death. FASEB J. 2004;18:1162–1164. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1551fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YL, Wang CY, Huang WC, Tsai CC, Chen CL, Shen CF, et al. Staphylococcus aureus induces microglial inflammation via a glycogen synthase kinase 3β-regulated pathway. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4002–4008. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00176-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherner M, Masliah E, Ellis RJ, Marcotte TD, Moore DJ, Grant I, et al. Neurocognitive dysfunction predicts postmortem findings of HIV encephalitis. Neurology. 2002;59:1563–1567. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000034175.11956.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CH, Schoenfeld BP, Bell AJ, Hinchey P, Kollaros M, Gertner MJ, et al. Pharmacological reversal of synaptic plasticity deficits in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome by group II mGluR antagonist or lithium treatment. Brain Res. 2011;1380:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou GN, Kokkevi A, Lykouras EP, Stefanis CN, Papadimitriou GN. Effects of lithium on memory. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138:847–848. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.6.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu B, Soncin F, Price BD, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Sequential phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3 represses transcriptional activation by heat shock factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30847–30857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Iversen SD, Goodwin GM. Sustained attention deficit in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:313–319. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.4.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan MP, Culbert AA, Cross DA, Corcoran SL, Yates JW, Pearce NJ, et al. Selective small molecule inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 modulate glycogen metabolism and gene transcription. Chem Biol. 2000;7:793–803. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contestabile A, Greco B, Ghezzi D, Tucci V, Benfenati F, Gasparini L. Lithium rescues synaptic plasticity and memory in Down syndrome mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:348–361. doi: 10.1172/JCI64650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews L, Patrick C, Achim CL, Everall IP, Masliah E. Molecular pathology of neuro-AIDS (CNS-HIV) Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:1045–1063. doi: 10.3390/ijms10031045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch PJ, Hung LW, Adlard PA, Cortes M, Lal V, Filiz G, et al. Increasing Cu bioavailability inhibits Aβ oligomers and tau phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:381–386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809057106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Freeman B, Shikani HJ, Bruno FP, Collado JE, Macias R, et al. Altered regulation of Akt signaling with murine cerebral malaria, effects on long-term neuro-cognitive function, restoration with lithium treatment. PLoS One. 2012;7:44117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash PK, Johnson D, Clark J, Orsi SA, Zhang M, Zhao J, et al. Involvement of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling pathway in TBI pathology and neurocognitive outcome. PLoS One. 2011;6:24648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Molecular pathways of neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1087753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ferrari GV, Chacón MA, Barría MI, Garrido JL, Godoy JA, Olivares G, et al. Activation of Wnt signaling rescues neurodegeneration and behavioral impairments induced by β-amyloid fibrils. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:195–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarno P, Axtell RC, Raman C, Roth KA, Alessi DR, Jope RS. Lithium prevents and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:338–345. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vasconcellos AP, Zugno AI, Dos Santos AH, Nietto FB, Crema LM, Gonçalves M, et al. Na+,K(+)-ATPase activity is reduced in hippocampus of rats submitted to an experimental model of depression: effect of chronic lithium treatment and possible involvement in learning deficits. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2005;84:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Ser T, Steinwachs KC, Gertz HJ, Andrés MV, Gómez-Carrillo B, Medina M, et al. Treatment of Alzheimer's disease with the GSK-3 inhibitor tideglusib: a pilot study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:205–215. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Aimone JB, Gage FH. New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:339–350. doi: 10.1038/nrn2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewachter I, Ris L, Jaworski T, Seymour CM, Kremer A, Borghgraef P, et al. GSK3β, a centre-staged kinase in neuropsychiatric disorders, modulates long term memory by inhibitory phosphorylation at serine-9. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;35:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhurst S, Maggirwar SB, Schifitto G, Gendelman HE, Gelbard HA. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 β (GSK-3β) as a therapeutic target in neuroAIDS. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2007;2:93–96. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias VV, Balanzá-Martinez V, Soeiro-de-Souza MG, Moreno RA, Figueira ML, Machado-Vieira R, et al. Pharmacological approaches in bipolar disorders and the impact on cognition: a critical overview. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126:315–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Qiao A, Fan GH. Indirubin-3'-monoxime rescues spatial memory deficits and attenuates β-amyloid-associated neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39:156–168. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon CE, Clifton GL, Lighthall JW, Yaghmai AA, Hayes RL. A controlled cortical impact model of traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;39:253–262. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Badri SM, Ashton CH, Moore PB, Marsh VR, Ferrier IN. Electrophysiological and cognitive function in young euthymic patients with bipolar affective disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:79–87. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldar-Finkelman H, Martinez A. GSK-3 inhibitors: preclinical and clinical focus on CNS. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:32. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsass P, Mellerup ET, Rafaelsen OJ, Theilgaard A. Effect of lithium on reaction time. A study of diurnal variations. Psychopharmacology. 1981;72:279–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00431831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel T, Hernández F, Avila J, Lucas JJ. Full reversal of Alzheimer's disease-like phenotype in a mouse model with conditional overexpression of glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5083–5090. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0604-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelsmann F, Katz J, Ghadirian AM, Schachter D. Lithium and memory: a long-term following study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988;8:207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom TY, Jope RS. Blocked inhibitory serine-phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3α/β impairs in vivo neural precursor cell proliferation. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everall IP, Bell C, Mallory M, Langford D, Adame A, Rockestein E, et al. Lithium ameliorates HIV-gp120-mediated neurotoxicity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:493–501. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falchook GS, Malone CM, Upton S, Shandera WX. Postmalaria neurological syndrome after treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:e22–e24. doi: 10.1086/375269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini A, Rosi MC, Grossi C, Luccarini I, Casamenti F. Lithium improves hippocampal neurogenesis, neuropathology and cognitive functions in APP mutant mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlenza OV, Diniz BS, Radanovic M, Santos FS, Talib LL, Gattaz WF. Disease-modifying properties of long-term lithium treatment for amnestic mild cognitive impairment: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198:351–356. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlenza OV, de Paula VJ, Machado-Vieira R, Diniz BS, Gattaz WF. Does lithium prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Drugs Aging. 2012;29:335–342. doi: 10.2165/11599180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AV, King MK, Palomo V, Martinez A, McMahon L, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitors reverse deficits in long-term potentiation and cognition in Fragile X mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgievska B, Sandin J, Doherty J, Mörtberg A, Neelissen J, Andersson A, et al. AZD1080, a novel GSK3 inhibitor, rescues synaptic plasticity deficits in rodent brain and exhibits peripheral target engagement in humans. J Neurochem. 2013;125:446–456. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal K, Vogt DL, Liang M, Shen Y, Lamb BT, Pimplikar SW. Alzheimer’s disease-like pathological features in transgenic mice expressing the APP intracellular domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18367–18372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907652106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de, Barreda E, Pérez M, Gómez Ramos P, de Cristobal J, Martín-Maestro P, Morán A, et al. Tau-knockout mice show reduced GSK3-induced hippocampal degeneration and learning deficits. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Murthy AC, Zhang L, Johnson EB, Schaller EG, Allan AM, et al. Inhibition of GSK3β improves hippocampus-dependent learning and rescues neurogenesis in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:681–691. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Duff K, Hardy KG, Perez-Tur J, Hutton M. Genetic dissection of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: amyloid and its relationship to tau. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:355–358. doi: 10.1038/1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–536. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto R, Senatorov V, Kanai H, Leeds P, Chuang DM. Lithium stimulates progenitor proliferation in cultured brain neurons. Neuroscience. 2003;117:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]