Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) is suggested to play an important role in primary headaches. It has been proposed that release of NO from satellite glial cells (SGCs) of the trigeminal ganglion (TG) could contribute to the pathogenesis of these headaches. The principal aim of this study was to investigate if the phosphodiesterase inhibitor Ibudilast (Ibu) and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (Vit D3) could interfere with NO release from trigeminal SGCs. Since glutamate is released from activated TG neurons, the ability of glutamate to alter NO release from SGCs was also investigated. To study this, we isolated SGCs from the TG of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, provoked NO release from SGCs with forskolin (FSK; 0.1, 1, 10 μM), and examined the effect of graded concentrations of Ibu (1, 10, 100 μM), Vit D3 (5, 50, 500 nM), and glutamate (10, 100, 1000 μM). Our results indicate that both Ibu and Vit D3 are capable of attenuating the FSK-mediated increased NO release from SGCs after 48 hours of incubation. Lower glutamate concentrations (10 and 100 μM) significantly decreased NO release not only under basal conditions after 24 and 48 hours, but also after SGCs were stimulated with FSK for 48 hours. In conclusion, NO release from SGCs harvested from the TG can be attenuated by glial modulators and glutamate. As NO is thought to increase TG neuron excitability, the findings suggest that targeting SGCs may provide a novel therapeutic approach for management of craniofacial pain conditions such as migraine in the future.

Keywords: Ibudilast, vitamin D3, migraine, headache, satellite glial cells, nitric oxide, glutamate, glial modulation

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a volatile free radical and an important messenger that is considered a putative key molecule in the pathophysiology of primary headaches, such as migraine headache [1]. Evidence that NO plays a key role in the pathogenesis of headaches includes the observations that intravenous infusion of NO donors in migraine patients leads to the development of a headache with characteristics similar to migraine attacks [2,3] and that increased levels of NO are found in the blood of migraineurs during spontaneous attacks [4]. Furthermore, inhibition of the enzymes responsible for NO production, the nitric oxide synthases (NOS), has been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of migraine patients and in preclinical migraine models [5,6].

The NOS enzymes are broadly divided into two categories; the constitutive type expressed by neurons (nNOS) and endothelial cells (eNOS), and the inducible type (iNOS) expressed upon stimulation in a variety of tissues [7]. While nNOS and eNOS rapidly produce small amounts of NO, iNOS produces copious amounts for days, which can give rise to tissue damage and pain [8]. It has been suggested that NO release from glial cells that reside in the central nervous system (CNS), and also in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), could contribute to pain [9,10].

There is increasing focus on glial cells of the PNS, most notably satellite glial cells (SGCs), which now are considered potential contributors to abnormal pain processing [11]. The SGCs are non-neuronal cells found in sensory and autonomic ganglia, where they completely surround and ensheath neuronal cell bodies [12]. It has been demonstrated that SGCs of the trigeminal ganglion (TG) respond to peripheral noxious stimuli with an increased expression of e.g. glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), purinergic receptors, and gap junction proteins [13-15]. Some responses seen in SGCs may be caused by local neuronal release of neuropeptides such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). In fact, CGRP, which is involved in migraine pathophysiology [16], was shown to increase production and release of NO from trigeminal SGCs in vitro [10,17]. This has been suggested to be an important factor for the development of peripheral sensitization not only because NO can act on both neurons and SGCs to further increase the release of neuro- and gliotransmitters [18,19] but also because NO directly affects excitability of neurons [20]. Collectively, observations like these have refocused attention on the trigeminal SGCs as potential contributors to the underlying cause of peripheral sensitization as seen in e.g. migraine headache and it has been speculated that SGCs could be novel therapeutic targets [19,21]. Nevertheless, only a few investigations of NO release from SGCs and its modulation by application of compounds that can affect glial activity have been undertaken.

The aim of the current study was to determine whether NO release from isolated trigeminal SGCs can be attenuated by agents that are known to suppress/modulate certain properties of glial cells; namely the phosphodiesterase inhibitor Ibudilast (Ibu) [22] and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (Vit D3) [23]. Since TG neurons release Glu [24] and SGCs express Glu receptors [24-26] the release of NO from the SGCs following stimulation with Glu was also investigated.

Materials and methods

The experimental protocol was approved by the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee (approval number A11-0279). The study was performed in accordance with the guidelines established by the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate, Canadian Council on Animal Care, and the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Satellite glial cell isolation

Trigeminal ganglia were excised from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, CA and Taconic, DK; n = 14, body weight of 265-305 g) and SGCs were isolated based on a previously described method with only minor modifications [19]. Initially, rats were deeply anaesthetized with 4% isoflurane (Baxter Corporation, CA) and the circulatory system was flushed with 100 mL cold (4°C) heparinized isotonic saline using a transcardial perfusion technique. Both ganglia were aseptically removed, cut into smaller pieces of tissue, and immediately suspended in 5 mL ice-cold PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Sigma Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen, CA) and glucose (6 g/L). Next, tissue was digested in a collagenase solution (5 mg/mL; Sigma Aldrich, USA) for 15 min at 37°C and then for 10 min at 37°C in 0.125% trypsin (Invitrogen, CA), where a DNAse solution (Ambion, CA) was added during the last 5 min of incubation. After centrifugation for 5 min at 1300 RPM, the pellet was resuspended in 5 mL Ham’s F12 medium (Invitrogen, CA) supplemented with 10% endotoxin-free heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Invitrogen, CA) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (complete growth medium). The tissue digests were mechanically dissociated using a syringe, transferred to 25 cm2 culture flasks, and incubated for three hours at 37°C to separate SGCs from neurons. Thus, the SGCs remained attached to the bottom of the culture flask, while neurons and the remaining tissue debris were floating in the medium, which then was decanted. Finally, 5 mL of complete growth medium was added, which was renewed after 24 hours and every second day from thereafter.

In all experiments of NO release from SGCs, cells were counted with a haemocytometer and seeded at a density of 200,000 cells/well in uncoated 24 well-plates.

Nitric oxide release assays

Studies of evoked NO release from SGCs were based on previously published methodologies [10,17,24]. After reaching 80-90% confluence, the SGCs were washed in PBS and treatment medium was applied. Cells were treated with serum and additive free Dulbecco’s Modified Essential Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, CA) containing either graded concentrations of forskolin (FSK; 0, 0.1, 1, 10 μM; Sigma Aldrich, USA) or Glu (0, 10, 100, 1000 μM; Sigma Aldrich, USA), which were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and DMEM, respectively. The final DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.1% when FSK was diluted into the culture medium. Duplicate samples of 50 μL were withdrawn after 48 hours of incubation for FSK-stimulated SGCs and after 15 min, 4, 24, and 48 hours of incubation for Glu-stimulated SGCs.

The NO concentration in each sample was immediately determined by the colorimetric Griess Reagent System (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, a 50 μL cell-free sample was mixed with an equal volume of sulfanilamide and incubated for 10 min at ambient temperature (20-22°C). Afterwards, 50 μL of N-1-napthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride was added and the mixture was re-incubated for 10 min. Finally, the absorbance at 525 nm was determined by spectrophotometry using an Ultraspec 3100 Pro spectrophotometer (Biochrom, USA).

Nitric oxide inhibition assays

The effect of Ibu (Sigma Aldrich, USA), Vit D3 (Sigma Aldrich, USA), and Glu on FSK-evoked NO release from SGCs was also investigated. Both Ibu and Vit D3 were dissolved as stock solutions in DMSO, whereas Glu was dissolved in DMEM. The final DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.3% when the compounds were diluted into the culture medium for these assays.

The SGCs were washed with PBS, whereafter treatment media were applied and the SGCs were incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. Treatment media consisted of DMEM alone (vehicle) and DMEM containing 10 μM FSK alone or together with Ibu (1, 10, 100 μM), Vit D3 (5, 50, 500 nM), or 100 μM Glu. These concentrations were based on preliminary results and previously published work [27-29]. The NO content in each sample was determined by the Griess Reagent System as described above.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed on whole-cell lysates to investigate whether the FSK-evoked increases in NO release and its modulation by Ibu, Vit D3, and Glu were mediated by regulation of the iNOS protein expression.

The SGCs were cultured in 25 cm2 culture flasks until 80-90% confluence was reached. At this point, SGCs were washed in PBS and treated with DMEM alone (vehicle) or DMEM containing FSK (10 μM), FSK + Ibu (10 μM + 1 μM), FSK + Vit D3 (10 μM + 50 nM), or FSK + Glu (10 μM + 100 μM). After 48 hours of incubation, cells were lyzed in 100 μl Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) buffer for 30 min on ice. The lysates were then centrifuged at 10,000 RPM for 20 min at 4°C and cell-free supernatants were mixed with a reducing loading buffer (ratio of 1:4) and heated to 85°C for 10 min. Samples were loaded onto a 4% stacking/10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-Polyacrylamide separation gel together with a prestained standard protein ladder (BioRad, DK). Electrophoresis was performed for 10 min at 120 V and then for 40 min at 180 V and afterwards proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using an iBlot Gel Transfer Stack Mini kit and an iBlot Gel Transfer device (Invitrogen, DK).

Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dried milk (Fluka, Sigma Aldrich, DK) for 30 min, washed with PBS, and then incubated overnight at 4°C in 1% blocking buffer containing a rabbit anti-iNOS antibody (1:200; Abcam, DK) and a mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:5000; Sigma Aldrich, DK). The following day, membranes were washed thoroughly with PBS and iNOS bands were visualized with an anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated antibody (1:5000; Sigma Aldrich, DK), whereas β-actin bands (loading control) were visualized with an anti-mouse HRP conjugated antibody (1:5000; Dako, DK).

Images were obtained on a Kodak 4000 MM Pro Image Station and band intensities were quantified using ImageJ on a Macintosh computer.

Cell viability assay

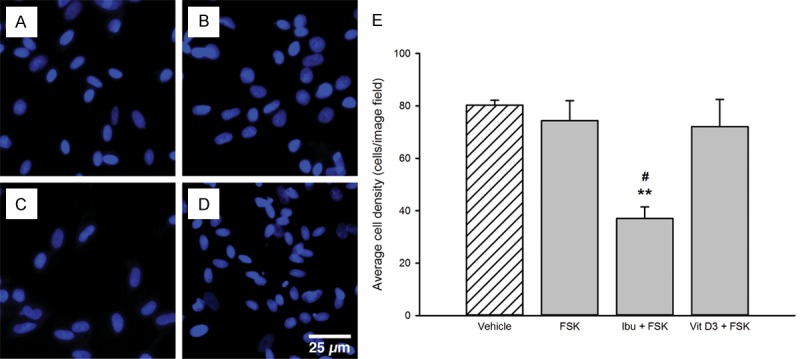

To determine whether application of the highest concentrations of inhibitors (Ibu and Vit D3) might be toxic, a cell viability assay was performed. Cells isolated from three different rats were seeded at a density of 40,000 cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated for 48 hours in DMEM alone (vehicle) or DMEM containing 10 μM FSK alone or together with 100 μM Ibu or 500 nM Vit D3. Afterwards, cells were washed in PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min on ice. Cells were then stained with the nuclear dye Hoechst 33342 (1:5000; Invitrogen, DK) for 20 min at room temperature. The average cell density, which was defined as the number of cells/image field, was assessed by capturing at minimum five non-overlapping images from each treatment condition followed by manual counting of the cell nuclei within each field of view. Only clearly distinguishable nuclei were included in the data analysis. All images were captured at 200x magnification using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 40 CFL, Zeiss, DK) equipped with a digital camera (Axiocam Cm1, Zeiss, DK).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in a blinded fashion. Experimental procedures were repeated on cells isolated from at least three different animals to ensure reproducibility. Data were statistically analyzed by a one-way repeated measures ANOVA using SigmaPlot v. 11 (Systat, USA) for Microsoft Windows 7. When the ANOVA analysis reached the predefined significance level, the Bonferroni post hoc multiple comparison test was used to identify significant between-treatment differences. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all experimental assays.

Results

Nitric oxide release assays

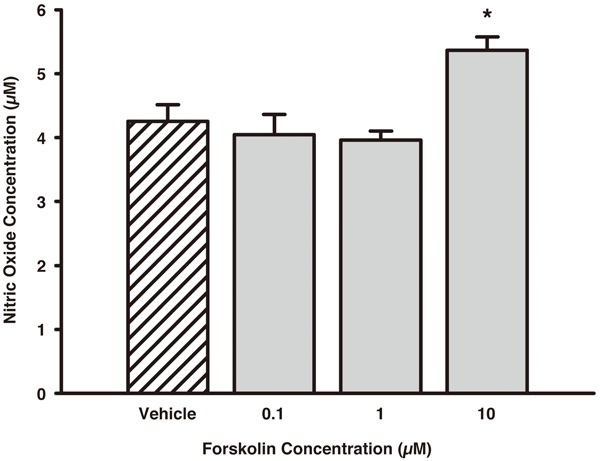

The SGCs were initially treated with graded concentrations of FSK in an attempt to provoke NO release into the culture medium. Application of vehicle medium resulted in a baseline NO release of 4.26 ± 0.26 μM after 48 hours of incubation. When the SGCs were treated with either 0.1 or 1 μM FSK the NO release was not significantly different from vehicle treatment (4.05 ± 0.32 μM and 3.96 ± 0.14 μM, respectively; p > 0.05 vs. vehicle). In contrast, 10 μM FSK significantly increased the NO release to 5.37 ± 0.21 μM (p = 0.032 vs. vehicle) (Figure 1). Based on these results, 10 μM FSK was used as the activating stimulus for subsequent inhibition assays.

Figure 1.

Concentration-response of FSK on NO release from isolated trigeminal SGCs. The SGCs were treated with vehicle medium or graded concentrations of FSK (0.1, 1, 10 μM) and incubated for 48 hours. Only 10 μM FSK significantly increased the NO release from the SGCs compared to vehicle treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 vs. vehicle. FSK, Forskolin; NO, Nitric Oxide; SGCs, Satellite Glial Cells.

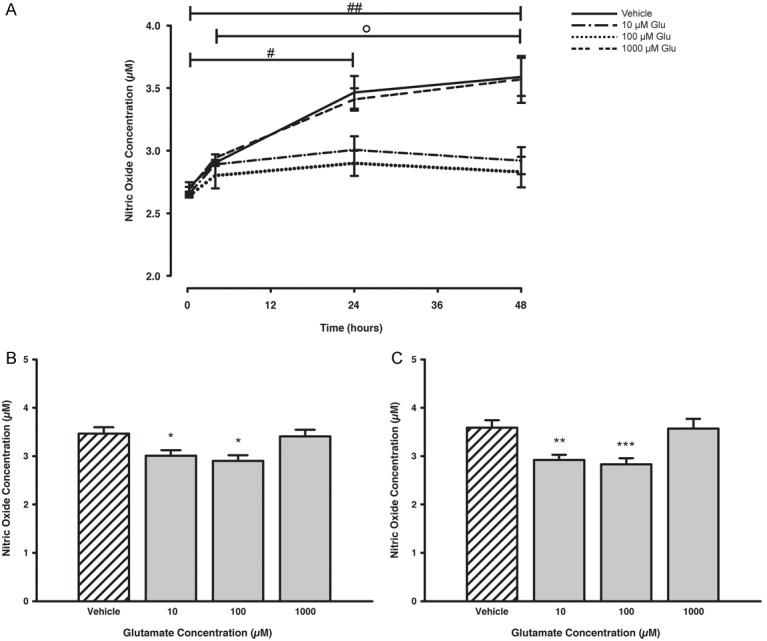

The effect of elevated Glu concentrations on NO release from SGCs was investigated subsequently. Lower concentrations of Glu (10 and 100 μM) decreased NO release over time, compared with vehicle treatment, whereas 1000 μM Glu did not significantly alter NO release over the 48-hour time-course compared to the vehicle (Figure 2A). The bar plots in Figure 2B and 2C provide a more detailed view of the concentration-response relationship for treatment with Glu at the 24 and 48 hour time-points.

Figure 2.

Time- and concentration-dependent release of NO from trigeminal SGCs after stimulation with Glu. Treatment with 10 and 100 μM Glu lowered the NO release in a time-dependent manner, whereas treatment with 1000 μM Glu did not affect the NO release, compared to vehicle treatment (A). After 24 (B) and 48 hours (C) of incubation the NO release was significantly attenuated for SGCs treated with 10 and 100 μM Glu, compared to vehicle levels. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). #, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.01 vs. 15 min; ○, p < 0.05 vs. 4 hours; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 vs. vehicle. Glu, Glutamate; NO, Nitric Oxide; SGCs, Satellite Glial Cells.

Nitric oxide inhibition assays

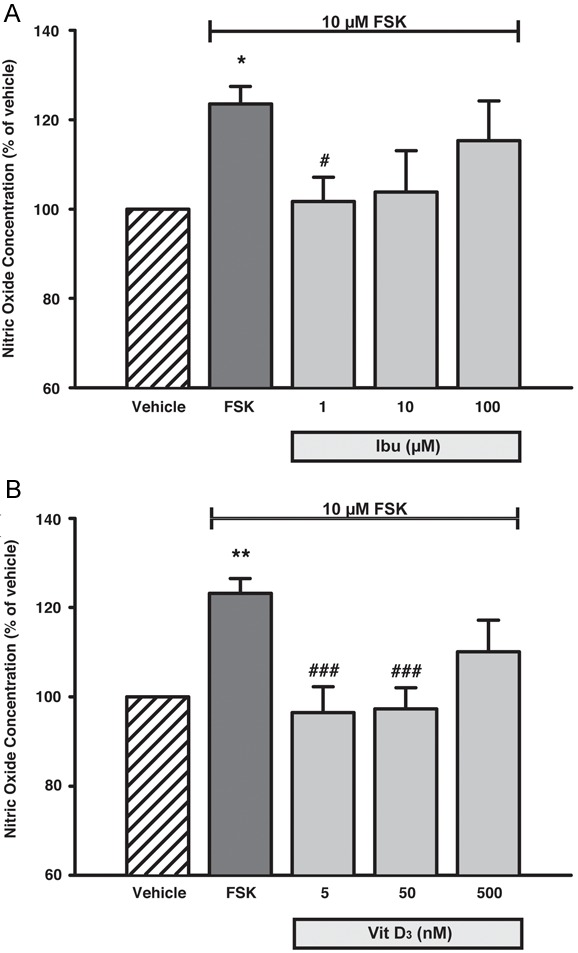

The effect of Ibu and Vit D3 on NO release was also investigated. Co-application of 1 μM Ibu resulted in a complete and significant reversal of the FSK-mediated increased NO release (reversed to 101.7 ± 5.5% of vehicle; p = 0.035 vs. FSK alone). Treatment with 10 and 100 μM Ibu appeared to interfere with the NO release (103.8 ± 9.2% and 107.3 ± 4.8% of vehicle, respectively), however, no statistically significant difference between these treatments and the FSK-stimulated SGCs could be established (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent decrease in NO release from trigeminal SGCs after treatment with Ibu and Vit D3. FSK stimulation facilitated a pronounced and significant increase in the NO release from the SGCs, which could be completely or partially reversed by co-treatment with the Ibu and Vit D3 (A, B). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 vs. vehicle; #, p < 0.05; ###, p ≤ 0.001 vs. FSK. FSK, Forskolin; Ibu, Ibudilast; Vit D3, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; SGCs, Satellite Glial Cells.

Application of 5 or 50 nM Vit D3 completely abolished the FSK-mediated increase in NO release (returned to 96.5 ± 5.8% and 97.3 ± 4.7% of vehicle; p = 0.001). However, treatment with a 500 nM Vit D3 was found to bring about only a partial non-significant inhibition of the FSK-mediated increased NO release (to 110.1% ± 7.1 of vehicle) (Figure 3B).

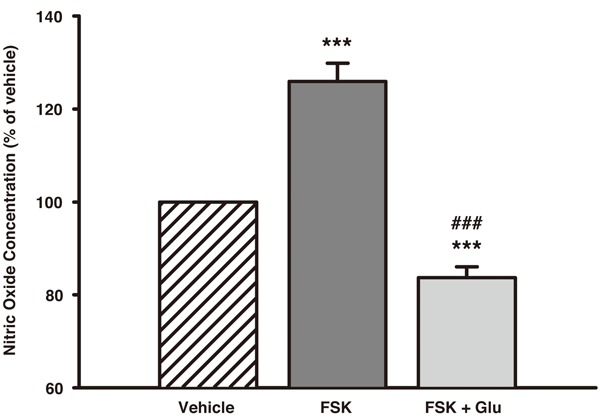

Because 100 μM Glu was found to suppress the basal NO release in the release studies, we asked whether the same concentration of Glu also would interfere with the increase in NO release facilitated by FSK. Indeed, when concomitantly treated with 10 μM FSK and 100 μM Glu the SGCs displayed a significantly lower NO liberation (83.7 ± 5.3% of vehicle), compared to both FSK-stimulated SGCs (p < 0.001) but also untreated SGCs (p < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of concomitant treatment with 10 μM FSK and 100 μM Glu on NO release from trigeminal SGCs. FSK alone caused a prominent and significant increase in NO from the SGCs, however, this increase could be completely antagonized when 100 μM Glu was added to the treatment medium. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). ***, p < 0.001 vs. vehicle; ###, p < 0.001 vs. FSK. FSK, Forskolin; Glu, Glutamate; NO, Nitric Oxide; SGCs, Satellite Glial Cells.

Western blot of iNOS expression

The iNOS protein was detectable but the expression was relatively low for all conditions tested even when high protein content was loaded (data not shown). These results indicate that, at best, iNOS expression is rather low in untreated SGCs and that the expression was not considerably affected by either of the treatments applied in the current experimental setup.

Cell viability assay

The average cell density in control wells was 80.3 ± 1.9 cells/image (Figure 5E). The cell viability was not significantly altered for SGCs treated with FSK (74.4 ± 7.6 cells/image) or FSK + Vit D3 (72.1 ± 10.3 cells/image) (Figure 5E). On the contrary, the cell viability was significantly lowered to 37.1 ± 4.4 cells/image when SGCs were treated with FSK + Ibu (p < 0.01 vs. control; Figure 5C and 5E). This indicates that the combination of FSK + Ibu, but not FSK alone or FSK + Vit D3, is toxic to SGCs under the culture conditions of this study.

Figure 5.

Satellite glial cell viability after treatment with high concentrations of FSK, Ibu, and Vit D3. Panels A-D show representative florescence images of SGCs labeled with the nuclear stain Hoechst after 48 hours of treatment with control medium (A), 10 μM FSK (B), 10 μM FSK + 100 μM Ibu (C), and 10 μM FSK + 500 nM Vit D3 (D). There was a notable drop in the number of viable cells in wells treated with the combination of FSK and Ibu (C, E), compared to cells treated with control medium (A), FSK alone (B), or together with Vit D3 (D). Data in (E) are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). **, p < 0.01 vs. control; #, p < 0.05 vs. FSK alone and FSK + Vit D3. FSK, Forskolin; Ibu, Ibudilast; Vit D3, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; SGCs, Satellite glial cells.

Discussion

Nitric oxide release assays

Nitric oxide, which is an important messenger molecule that is considered integral to the pathophysiology of migraine [1], was released from trigeminal SGCs after stimulation with the adenylyl cyclase activator FSK. In agreement with this, Li et al. [17] showed that NO release could be evoked from SGCs when treated with FSK for 48 hours. Previously, it was reported that agents that increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), such as CGRP or FSK, facilitated up-regulation of iNOS in SGCs from the TG and that this up-regulation was responsible for the increased NO liberation [17]. Nevertheless, our western blot analysis failed to verify this and instead indicated that the iNOS expression was rather low and comparable in both the untreated SGCs and those treated with FSK.

This observation raises the possibility that one of the other NOS isoforms, i.e. nNOS or eNOS, may be responsible for the increased NO release as observed in our study. It is unlikely that nNOS contributes to this process, since treatment with a selective inhibitor of nNOS was found not to affect the NO release from trigeminal SGCs previously [17]. Moreover, it is unlikely that eNOS was responsible for the release, since this isoform rapidly produces small amounts of NO. Therefore, it is speculated that the FSK-mediated increased NO release is facilitated through iNOS up-regulation, which, however, was modest under the present experimental conditions and therefore not picked up in the western blot analysis.

The activation of SGCs within the TG is likely coupled to and dependent on signals from the neurons they surround. However, it still remains uncertain which substances can be released from the neuronal cell bodies located in the TG in vivo and how these substances would affect the SGCs. Nevertheless, it has been shown that neurotransmitters such as Glu or adenosine triphosphate (ATP) can be released locally from the neurons in the ganglion [24,30,31]. It has also been speculated that CGRP released from trigeminal neurons within the TG could interact with CGRP receptors on adjacent SGCs, to increase intracellular cAMP levels, and facilitate the release of NO [10]. NO is known to promote both production and release of CGRP from trigeminal neurons [18] and to increase the secretion of pro-inflammatory substances from SGCs [19], which may initiate an inflammatory loop within the TG. This could be a contributing factor for the development of peripheral sensitization, which hypothetically could link such events to the pathophysiology of migraine and other craniofacial pain conditions.

Effect of glutamate on nitric oxide release

We also investigated the effect of Glu on the NO release and found that application of lower concentrations (10 and 100 μM) decreased NO release from the SGCs and that 100 μM Glu attenuated the FSK-mediated increase in NO release as well. These results cannot be fully explained with the experiments conducted in the present study, however, the data could be interpreted as a negative feedback mechanism given that NO released from SGCs could excite TG neurons to release various neurotransmitters, including Glu. This inhibitory action of Glu may be elicited by activation of group II and/or III inhibitory metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) expressed by the SGCs [24,25]. Indeed it is known that activation of group III mGluRs leads to inhibition of FSK-induced cAMP accumulation in e.g. microglia [32] and accordingly, the Glu-mediated attenuation in the NO release as observed in this study could be interpreted as a response mediated by inhibitory mGluRs. An alternative explanation is that the decrease in NO result was a result of decreased viability of SGCs, and consequently a decrease in the cell number, after treatment with 10 and 100 μM Glu. However, since a recent study demonstrated that SGCs were viable after treatment with 200 μM Glu [24], it seems unlikely that cell toxicity can explain the decreased NO release observed in the present study.

Application of the highest concentration of Glu tested in the current study (1000 μM), seemed to facilitate a recovery in the NO release, returning this to levels equivalent of control cells. While the cause for this recovery is unknown at present, it may be that, at higher concentrations, Glu activates not only mGluRs but also ionotropic glutamate receptors such as N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which are expressed on SGCs [24,26,33]. Since, Ca2+-dependent NO formation has been reported in glial cells previously [34], sufficient activation of NMDA receptors may lead to increased NO production and release from the SGCs in the current setup.

To our knowledge, it has not yet been documented whether Glu concentrations similar to those used in vitro here are present in the TG. However, Glu concentrations in the plasma have been reported to increase to as much as 130 μM during for example migraine attacks [35]. Moreover, since vesicular release of Glu from TG neurons has been suggested to occur within sensory ganglia as well [24], it is conceivable that intraganglionic Glu levels can reach, or even locally exceed, these plasma levels. Therefore, the effects of Glu described on SGCs here may be of pathophysiological relevance for craniofacial pain conditions such as migraine headache.

Nitric oxide inhibition assays

Ibu and Vit D3 were found to significantly attenuate the FSK-mediated increase in NO release. Ibu is a relatively non-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor (PDEI) and glial attenuator that is believed to exert its effects through inhibition of the enzymes responsible for inactivation and degradation of cAMP [36]. Previous studies have reported concentration-dependent inhibition of NO release from glial cells in the CNS, which might be due to down-regulation of the iNOS expression upon treatment with Ibu [27,37]. Our results somewhat disagree with these concentration-dependent effects of Ibu since we found that only 1 μM Ibu was capable of significantly affecting the NO release, whereas it has previously been shown that 100 μM Ibu is the most efficacious in inhibiting NO release [27,37]. There may not be a straight-forward explanation for this inconsistency, however, it may be due to differences in the applied methods such as differences in the glial cell type under study or the age and species of animals used. In addition, we found that the combination of 10 μM FSK and 100 μM Ibu was toxic to the SGCs. Thus, it may be that it is the combination of these two compounds that gives rise to the results seen in the present study compared with previous studies.

While the concentrations Ibu used in this study are in agreement with previous in vitro experiments [27,37,38], they are ~2-200-fold higher than the plasma concentrations reported in animals [38] and ~4-400-fold higher than concentrations achieved in humans after repeated Ibu administration [39]. Hence, whether similar effects of Ibu on SGCs can be demonstrated in vivo and if these effects are important for craniofacial pain relief, remain to be determined.

The effect of Vit D3 on the NO release was also investigated and we found that while 5 and 50 nM Vit D3 effectively attenuated the NO release, treatment with 500 nM did not significantly affect the NO release. This U-shaped bimodal concentration-response relationship of Vit D3 is likely to represent non-specific, rather than toxic, effects of Vit D3 at higher supra-physiologic concentrations, since we did not detect any significant decline in the number of viable SGCs after treatment with a high concentration of Vit D3. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate of the effects of Vit D3 on SGCs. It has, however, been reported that similar concentrations of Vit D3 were not toxic to isolated neurons but that non-specific effects occurred at higher concentrations [28]. This information parallels well with the results of the current study, showing that although not toxic to the SGCs, 500 nM Vit D3 was not as effective as 5 and 50 nM in blocking NO release from SGCs, potentially due to non-specific effects of Vit D3 at this concentration. However, the physiologic importance of these non-specific effects of Vit D3 is not clear since achieving a plasma concentration of 500 nM is highly improbable due to dose limiting side effects of Vit D3 in humans [40].

The observation that Vit D3 effectively reduced NO release from the SGCs is in good agreement with previous studies focusing on CNS-derived glial cells, where Vit D3 was found to decrease iNOS expression in vivo and also decrease NO release in vitro [23,41]. However, it has also been reported that the effects of Vit D3 on NO release from astrocytes can be ascribed to up-regulation of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) rather than down-regulation of iNOS [41], which indicates that there may be more than one mechanism by which Vit D3 regulates the NO release from glial cells.

There is an increasing interest and acknowledgement of the neuroprotective effects of Vit D3 [42]. In addition, an association between Vit D3 deficiency and pain conditions, including headaches has been found [43] and there are sporadic reports on the role of Vit D3 in headache management [44,45]. Based on the present findings, Vit D3 could offer an additional protective role in the nervous system by interfering with the release of NO from SGCs in the TG, which in the present study was demonstrated in vitro using concentrations Vit D3 (5-50 nM) that are achievable in the plasma of animals and humans [40,46,47].

Conclusion

Findings from the present study indicated that FSK can evoke an increased NO release from trigeminal SGCs, which could be modulated by Ibu, Vit D3, and Glu. Given the putative role of NO in craniofacial pain conditions such as migraine, these observations may help in understanding the role of SGCs in vivo and could be relevant for the identification of new therapeutic approaches in targeting these cells in particular.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Meg Duroux, Michael Henriksen, and Jeppe Nørgaard Poulsen from the Laboratory for Cancer Biology, Department of Health Science and Technology, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark for their help and technical support. This research was supported by the 2010 FSS grant from the Danish Research Council to PG and 2011 annual grant from the Oticon Foundation to JCL.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Olesen J. The role of nitric oxide (NO) in migraine, tension-type headache and cluster headache. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;120:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christiansen I, Daugaard D, Lykke Thomsen L, Olesen J. Glyceryl trinitrate induced headache in migraineurs - relation to attack frequency. Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:405–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olesen J, Iversen HK, Thomsen LL. Nitric oxide supersensitivity: a possible molecular mechanism of migraine pain. Neuroreport. 1993;4:1027–1030. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarchielli P, Alberti A, Codini M, Floridi A, Gallai V. Nitric oxide metabolites, prostaglandins and trigeminal vasoactive peptides in internal jugular vein blood during spontaneous migraine attacks. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:907–918. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatt DK, Gupta S, Jansen-Olesen I, Andrews JS, Olesen J. NXN-188, a selective nNOS inhibitor and a 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonist, inhibits CGRP release in preclinical migraine models. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:87–100. doi: 10.1177/0333102412466967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lassen LH, Ashina M, Christiansen I, Ulrich V, Grover R, Donaldson J, Olesen J. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition: a new principle in the treatment of migraine attacks. Cephalalgia. 1998;18:27–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1801027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saha RN, Pahan K. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene in glial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:929–947. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naik AK, Tandan SK, Kumar D, Dudhgaonkar SP. Nitric oxide and its modulators in chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;530:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy S. Production of nitric oxide by glial cells: regulation and potential roles in the CNS. Glia. 2000;29:1–13. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(20000101)29:1<1::aid-glia1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vause CV, Durham PL. CGRP stimulation of iNOS and NO release from trigeminal ganglion glial cells involves mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Neurochem. 2009;110:811–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohara PT, Vit JP, Bhargava A, Romero M, Sundberg C, Charles AC, Jasmin L. Gliopathic pain: when satellite glial cells go bad. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:450–463. doi: 10.1177/1073858409336094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanani M. Satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia: from form to function. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:457–476. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunjigake KK, Goto T, Nakao K, Kobayashi S, Yamaguchi K. Activation of satellite glial cells in rat trigeminal ganglion after upper molar extraction. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2009;42:143–149. doi: 10.1267/ahc.09017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kushnir R, Cherkas PS, Hanani M. Peripheral inflammation upregulates P2X receptor expression in satellite glial cells of mouse trigeminal ganglia: A calcium imaging study. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrett FG, Durham PL. Differential expression of connexins in trigeminal ganglion neurons and satellite glial cells in response to chronic or acute joint inflammation. Neuron Glia Biol. 2008;4:295–306. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X09990093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durham PL, Masterson CG. Two Mechanisms Involved in Trigeminal CGRP Release: Implications for Migraine Treatment. Headache. 2013;53:67–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Vause CV, Durham PL. Calcitonin gene-related peptide stimulation of nitric oxide synthesis and release from trigeminal ganglion glial cells. Brain Res. 2008;1196:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellamy J, Bowen EJ, Russo AF, Durham PL. Nitric oxide regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide gene expression in rat trigeminal ganglia neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2057–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capuano A, De Corato A, Lisi L, Tringali G, Navarra P, Dello Russo C. Proinflammatory-activated trigeminal satellite cells promote neuronal sensitization: relevance for migraine pathology. Mol Pain. 2009;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy D, Strassman AM. Modulation of dural nociceptor mechanosensitivity by the nitric oxide-cyclic GMP signaling cascade. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:766–772. doi: 10.1152/jn.00058.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jasmin L, Vit JP, Bhargava A, Ohara PT. Can satellite glial cells be therapeutic targets for pain control? Neuron Glia Biol. 2010;6:63–71. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X10000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzumura A, Ito A, Yoshikawa M, Sawada M. Ibudilast suppresses TNFalpha production by glial cells functioning mainly as type III phosphodiesterase inhibitor in the CNS. Brain Res. 1999;837:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcion E, Nataf S, Berod A, Darcy F, Brachet P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat central nervous system during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;45:255–267. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kung LH, Gong K, Adedoyin M, Ng J, Bhargava A, Ohara PT, Jasmin L. Evidence for Glutamate as a Neuroglial Transmitter within Sensory Ganglia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlton SM, Hargett GL. Colocalization of metabotropic glutamate receptors in rat dorsal root ganglion cells. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:780–789. doi: 10.1002/cne.21285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivanusic JJ, Beaini D, Hatch RJ, Staikopoulos V, Sessle BJ, Jennings EA. Peripheral N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors contribute to mechanical hypersensitivity in a rat model of inflammatory temporomandibular joint pain. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizuno T, Kurotani T, Komatsu Y, Kawanokuchi J, Kato H, Mitsuma N, Suzumura A. Neuroprotective role of phosphodiesterase inhibitor ibudilast on neuronal cell death induced by activated microglia. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brewer LD, Thibault V, Chen KC, Langub MC, Landfield PW, Porter NM. Vitamin D hormone confers neuroprotection in parallel with downregulation of L-type calcium channel expression in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:98–108. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00098.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neveu I, Naveilhan P, Jehan F, Baudet C, Wion D, De Luca HF, Brachet P. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates the synthesis of nerve growth factor in primary cultures of glial cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;24:70–76. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuka Y, Neubert JK, Maidment NT, Spigelman I. Concurrent release of ATP and substance P within guinea pig trigeminal ganglia in vivo. Brain Res. 2001;915:248–255. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02888-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao Y, Richter JA, Hurley JH. Release of glutamate and CGRP from trigeminal ganglion neurons: Role of calcium channels and 5-HT1 receptor signaling. Mol Pain. 2008;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor DL, Diemel LT, Pocock JM. Activation of microglial group III metabotropic glutamate receptors protects neurons against microglial neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2150–2160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02150.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castillo C, Norcini M, Martin Hernandez LA, Correa G, Blanck TJ, Recio-Pinto E. Satellite glia cells in dorsal root ganglia express functional NMDA receptors. Neuroscience. 2013;240:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agullo L, Baltrons MA, Garcia A. Calcium-dependent nitric oxide formation in glial cells. Brain Res. 1995;686:160–168. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00486-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campos F, Sobrino T, Perez-Mato M, Rodriguez-Osorio X, Leira R, Blanco M, Mirelman D, Castillo J. Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase: A new key in the dysregulation of glutamate in migraine patients. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:1148–1154. doi: 10.1177/0333102413487444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ledeboer A, Hutchinson MR, Watkins LR, Johnson KW. Ibudilast (AV-411). A new class therapeutic candidate for neuropathic pain and opioid withdrawal syndromes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:935–950. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.7.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshikawa M, Suzumura A, Ito A, Tamaru T, Takayanagi T. Effect of phosphodiesterase inhibitors on nitric oxide production by glial cells. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2002;196:167–177. doi: 10.1620/tjem.196.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ledeboer A, Liu T, Shumilla JA, Mahoney JH, Vijay S, Gross MI, Vargas JA, Sultzbaugh L, Claypool MD, Sanftner LM, Watkins LR, Johnson KW. The glial modulatory drug AV411 attenuates mechanical allodynia in rat models of neuropathic pain. Neuron Glia Biol. 2006;2:279–291. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X0700035X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rolan P, Gibbons JA, He L, Chang E, Jones D, Gross MI, Davidson JB, Sanftner LM, Johnson KW. Ibudilast in healthy volunteers: safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics with single and multiple doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:792–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muindi JR, Johnson CS, Trump DL, Christy R, Engler KL, Fakih MG. A phase I and pharmacokinetics study of intravenous calcitriol in combination with oral dexamethasone and gefitinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;65:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcion E, Sindji L, Leblondel G, Brachet P, Darcy F. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates the synthesis of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and glutathione levels in rat primary astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1999;73:859–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcion E, Wion-Barbot N, Montero-Menei CN, Berger F, Wion D. New clues about vitamin D functions in the nervous system. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:100–105. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knutsen KV, Brekke M, Gjelstad S, Lagerlov P. Vitamin D status in patients with musculoskeletal pain, fatigue and headache: a cross-sectional descriptive study in a multi-ethnic general practice in Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28:166–171. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2010.505407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thys-Jacobs S. Vitamin D and calcium in menstrual migraine. Headache. 1994;34:544–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3409544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thys-Jacobs S. Alleviation of migraines with therapeutic vitamin D and calcium. Headache. 1994;34:590–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3410590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muindi JR, Modzelewski RA, Peng Y, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Pharmacokinetics of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in normal mice after systemic exposure to effective and safe antitumor doses. Oncology. 2004;66:62–66. doi: 10.1159/000076336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chow EC, Quach HP, Vieth R, Pang KS. Temporal changes in tissue 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, vitamin D receptor target genes, and calcium and PTH levels after 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E977–989. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00489.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]