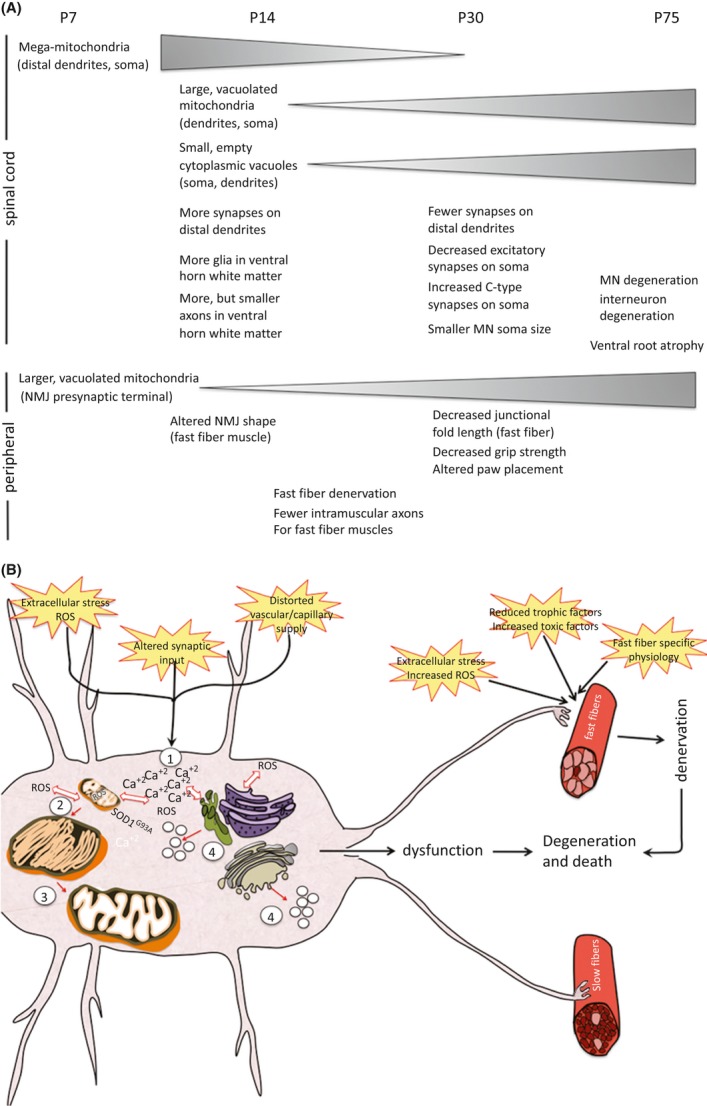

Figure 25.

(A) A summary of pathological events in central and peripheral components of the neuromuscular system of SOD1G93A mice and the time of their appearance is shown (see accompanying paper (doi: 10.1002/brb3.143) for description of pathology in the spinal cord). Triangles show either increases or decreases in the pathology over time. (B) A proposed sequence of initial pathology in MNs in SOD1G93A mice is shown. Altered synaptic input either alone or with a perturbed capillary supply and extracellular stress results in an imbalance of Ca2+ within the MN (1). This imbalance results in intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and together with the presence of the mutant SOD1 protein creates an environment that results in the formation of mega-mitochondria (2). The mitochondria are not able to resolve the “stress,” possibly because of their impairment by mutant SOD1, and thus become vacuolated (3). The imbalance of intracellular Ca2+ and generation of ROS can also initiate the unfolded protein response and ER stress resulting in vacuolization of smooth ER and Golgi (4). Together, these events result in MN dysfunction. MNs innervating fast muscle fibers also encounter events at the NMJ including extracellular stress and ROS, fast fiber-specific physiology and possibly a reduced supply of trophic factors or increased toxic factors that lead to muscle denervation. The combination of the denervation and MN dysfunction eventually leads to MN degeneration and death. While not shown in the diagram, the events contributing to MN dysfunction in the spinal cord most likely contribute to glial cell activation and/or dysfunction (e.g., decrease in astrocyte glutamate transporter) that further enhances disease pathology. With the exception of the vascular system, also not shown here are noncell (MN) autonomous contributions that may contribute to disease onset (e.g., astrocytes, Schwann cells).