Abstract

The Trp-cage, at 20 residues in length, is generally acknowledged as the smallest fully protein-like folding motif. Linking the termini by a two-residue unit and excising one residue affords circularly permuted sequences that adopt the same structure. This represents the first successful circular permutation of any fold of less than 50-residue length. As was observed for the original topology, a hydrophobic staple near the chain termini is required for enhanced fold stability.

Circular permutation of a protein structure consists of linking the N- and C-termini by an amide bond or a short peptide linker and cutting elsewhere in the sequence; a permutation is successful if the thus altered sequence forms the same fold. While both natural and designed examples of circular permutation are common for larger proteins, there appeared to be no examples for small (< 50 residue) protein folds per the CPDB database (http://sarst.life.nthu.edu.tw/cpdb/).1 There are examples of protein cyclizations in the 30 – 40 residue size range2 but these had not been cleaved at other sites. We recently suggested that circular permutation, by separating topology from sequence, could provide unique insights into folding pathways of small domains and presented preliminary data of successful permutation of the 35-residue villin headpiece and a 34-residue WW domain.3 The 20-residue Trp-cage fold4,5, appears to be the smallest fully protein-like fold and thus an ideal test system for the effects of both cyclization and circular permutation at the extreme lower limit of fold size.

The Trp-cage consists of an N-terminal α helix, a short 310 helix, a C-terminal poly-ProII helix, and has a hydrophobic core with a buried Trp indole ring at its center (see Fig. 1). It became a target of molecular dynamics simulated folding studies6 as soon as the structure was announced; it has now been the subject of computational studies by at least 30 additional groups and is viewed as a protein folding paradigm7. The original Trp-cage construct (TC5b, NLYIQ WLKDG GPSSG RPPPS) is only marginally stable with a low melting temperature (Tm = 42 °C) but continues to serve as the subject of both MD folding simulations8,9 and experimental studies7b,10 of folding. Indeed, more than 40 publications, largely computational MD folding studies, for this construct were reported during 2011 and first few months of 2012.11

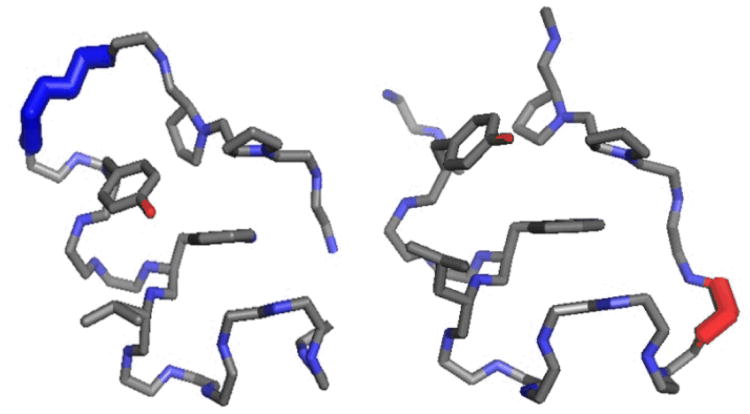

Fig. 1.

Comparison of a circularly permuted (left panel) and typical non-cyclic Trp-cage (right panel) illustrating the permutation strategy adopted. The conformational features in the left panel are from the X-ray structure11 of cyclo-TC1, those in the right panel are from an NMR structure5b: the full backbone and the heavy atoms of Y3, W6, L7, P18 and P19 (the buried Trp and the residues that form the hydrophobic core) are displayed. The added Gly-Gly loop of the cyclic species is shown in blue, the residue excised in producing circular permutants appears in red (right panel).

Both residue mutations5,12 and cyclization11 have been examined as Trp-cage fold stabilization strategies. The acyclic construct with the greatest fold stability, Tm = 83 °C, contains both D- and L-Ala mutations.5c A common feature of the more stable constructs is the replacement of longer sidechain residues in the helix with alanine; the DAYAQ WLADG GPSSG RPPPS sequence (TC13a, Tm = 62 °C)5b, which also has a helix-stabilizing Asp N-cap, serves as one starting point for the present study, the other starting point was a previously characterized11 cyclic construct.

Like many small proteins2b,13-15, the N- and C-termini of the Trp-cage fold are in close spatial proximity. This suggested cyclization as an alternative fold stabilization strategy and the use of circular permutation as a probe of the key interactions that are responsible for the remarkable fold stability and rapid folding of this system. Cyclization of the Trp-cage TC13a, with a Gly-Gly linker between the N- and C-termini provided a hyperstable Trp-cage.11 The resulting construct, cyclo-TC1 (cyclo-GDAYAQWLADGGPSSGRPPPSG, Tm = 95 °C), provided crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction and the resulting structures were essentially identical to the monomeric solution-state NMR structure and within a 0.45 Å backbone RMSD over residues 3 – 19 of prior NMR structures for acyclic Trp-cage species.

As a result, we posited that circular permutations should also be possible with a 2-residue linker between the original N- and C-termini. A potential benefit for rapid folding results from this linkage; formation of the Tyr3/Pro19 interaction, a hydrophobic staple providing in excess of 13 kJ/mol of fold stabilization5b, would present a smaller entropic penalty to folding in a circular permutant. The remaining question is the creation of the new termini. A cut must be made strategically, avoiding the bisection of secondary structural units such as the N-terminal helix and the C-terminal poly-Pro strand. On this basis, the scission would be in the G11-G12 or G15-R16 linkers between secondary structure elements. We opted for glycine excision rather than amide bond scission. Only excision of G15 afforded a sequence that formed a compact fold. This strategy (G15 excision) is illustrated in Fig. 1. We have not been able to rescue folding for any scission within the loop between the α and 310 helices.

Based on this strategy, the RPPPSGGDAYAQWLADGGPSS sequence (cp-TC1), with the Gly-Gly linker, was the first circular permutant prepared. We expected a significant decrease in fold stability as the Arg/Asp salt bridge, a known stabilizing feature in the Trp-cage12, must now include the presumably more mobile sidechain of an N-terminal residue. We also anticipated that the 310 helix (GPSS) might be less well formed due to C-terminal fraying. As in our prior Trp-cage studies, we used NMR structuring shifts, as chemical shift deviations (CSDs), to ascertain whether the same fold forms and to judge the extent of folding in the series of circularly permuted sequences prepared. The chemical shifts of the cyclo-TC1 served as the 100%-folded reference values. CSDs reflect both structure and the extent of folding. All of the diagnostic ring current shifts of the Trp-cage motif, including the downfield R16α,γ sites and the far upfield G11, P18 and P19 sites appear, with the same relative magnitudes but significantly reduced values in the permutant. Fig. 2 is the CSD comparison for sites along the sequences of cp-TC1 with cyclo-TC1 as the 100% folded control. In this and all subsequent figures, we continue to report residue data using the numbering for a non-permuted Trp-cage.

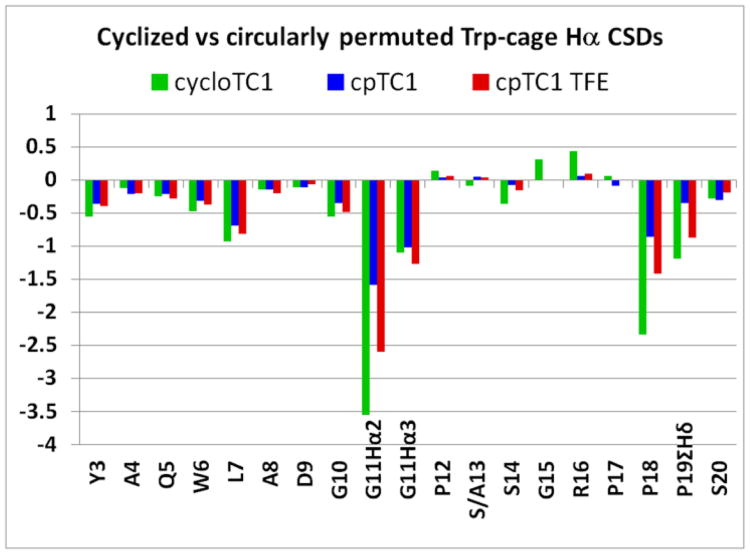

Fig. 2.

A comparison of structuring shifts (as CSDs at 280 K) along the sequence of the cyclic ‘starting point’ and a circularly permuted Trp-cage (cp-TC1). The data for cp-TC1 are shown for aqueous medium (pH 7) and upon addition of 30 vol-% trifluoroethanol. Except as noted, the CSDs are for the single Hα of each residue.

Construct cp-TC1 was examined at both acidic and neutral pH and with the addition of trifluoroethanol (TFE), to increase the intrinsic stability of the α helix. Acidification, protonating the N-capping aspartate and disrupting the Asp/Arg salt-bridge, was destabilizing. TFE-addition resulted in a notable increase in fold stability, just as it had in the case of early, less stable, non-permuted Trp-cage structures4,5b. Relying on the G11, P18 (Hα and Hβ3), and P19δ CSDs and assuming that their magnitudes relative to cyclo-TC1 reflect only fold population (χF) changes, the following extents of cage fold formation are obtained for cp-TC1: χF = 0.42 (at pH 7, 280K [dropping to 0.09 at 320K]), 0.20 (at pH 2, 280K), and 0.64 (at 280K, in 30 vol-% TFE/water). The structuring shifts within the helical segment and at the P19δ-CH2 reported a higher fold population than the G11 and P18 sites (Fig. 3), which suggests that the Y3/P19 hydrophobic staple may be present in a partially folded, helical state of this circular permutant.

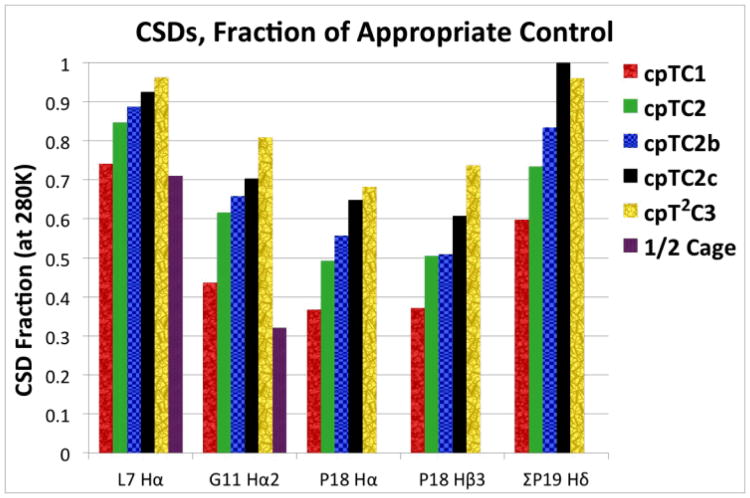

Fig. 3.

Local χF measures (CSDobs/CSDref) for Trp-cage circular permutants and a C-terminal truncated model (Ac-DAAAAAYA-QWLADGGPASG) of a half-cage structure. The folding measures are shown below each set of histograms. For each site, the analogs are shown in the following order, from left to right: – cp-TC1, cp-TC2 (RPPPSGGDAYAQWLADaGPSS, a = D-Ala), cp-TC2 with the following GGDA loop replacements – cp-TC2b, TADA and cp-TC2c, DUAA (U = Aib), cp-T2C3, and the half-cage model. The CSDref values are taken from χF ≥ 0.99 examples with each mutation. Additional comparisons of fold stabilities for the circular permutants appear in the Supporting Information (Table S1) together with CD melt comparisons for cp-TC2 and cp-T2C3 and their closest hyperstable, non-permuted analogs (Figure S1).

The pH effect (3.1 kJ/mol of fold-destabilization on acidification) is comparable to that observed12 in other Trp-cage constructs with a stabilizing D9/R16 interaction. An upfield shift at Trp-Hε1, reflecting its buried H-bonded state, also moves toward its random coil value on both acidification and warming. The fold stabilization associated with TFE-addition, as observed for prior Trp-cage constructs of marginal stability, indicates that that the intrinsic stability of the DAYAQWLAD helix is an essential component for fold stability. Thus it appears that a significantly less stable, but otherwise identical Trp-cage topology is retained on circular permutation.

As a further test of structural similarity, despite differing contact order, we examined how established Trp-cage fold stabilization strategies (and destabilizing mutations) affect the circular permutant. As expected, the S13→Ala mutation in the presumed 310 helix was stabilizing. Also in analogy to other Trp-cage species, there was notable fold destabilization upon replacing the buried S14 with an alanine (vide infra). The full list of ΔGU values observed and the sequences employed appear in the Supporting Information (Table 1S). The G10→D-Ala5c and P12→W16 mutations were particularly favorable. The D-Ala insertion at Gly10 had been demonstrated to increase ΔGU by 4 kJ/mol (ΔTm = 16 °C); the ΔTm effect in the circular permutant was identical but corresponded to ΔΔGU = 1.6 kJ/mol based on NMR shift measures of the fold population at 280K. We employed the G10→D-Ala change for all of the remaining mutational studies of the circular permutant. The P12W mutation has been reported16 to effect a similar degree fold stabilization in the case of TC5b. Species with the added Trp are named as Trp2-cages (‘T2C’).16 The latter was confirmed by performing the P12W mutation in two more stable Trp-cage constructs (Supporting Information, Table S1). In these cases, the CD melt provided additional measures of the fold stabilizing effect of the P12W mutation; ΔTm ≥ +9 °C which served as an initial expectation value for the effects that might appear for the same mutations in a circular permutant having the same fold. The circular permutant sequence was resynthesized with the G10a (cp-TC2) and G10a,P12W (cp-T2C3) mutations; the ΔTm. associated with the P12W mutation in this circular permutant was larger, +18°C. Key CSD comparisons for these species and two GGDA loop mutants appear in Fig. 3. Other CSD changes associated with P12W mutations appear in Fig. 2S.

An extensive series of alternatives to the SGGDA loop of cp-TC2 was examined; these included longer loops and specific residues selected to favor the backbone torsion angles (see Discussion and Supporting Information) observed through this region in the cyclo-TC1 crystal structures. We also explored the option of moving the Asp since it was no longer the N-cap of the longer helix observed for crystal structure of cyclo-TC1.

These studies, detailed in the Supporting Information, indicated that the original loop length was optimal and that, as expected, replacing the loop glycines with less flexible residues increased fold stability, particularly at higher temperatures. The loop with the greatest fold population at 320 K also included an Aib (U) residue, SDUAA (cp-TC2c, Tm = 48.5 °C).

The data in Fig. 3 clearly show the extent to which the fold population increased with these mutational optimizations. However, throughout the series of circular permutants there were indicators of either non-2-state behavior (a partially folded intermediate) or structuring in the “unfolded state”. In Fig. 3 these can be seen as the higher fractional CSDs observed for L7α and the P19 sites. These suggest the formation of a capped α helix even in the unfolded state. Additional examples are upfield shifts observed at G11Hα3 and the P12CδH2. For example, the CSDs observed for the less upfield G11Hα are, in the same order as in Fig. 3: −1.021, −1.342, −1.367, −1.468, −1.112, and −1.034 – all comparable to or larger than the CSD observed for cyclo-TC1 (−1.10 ppm) even though the other CSD measures of cage formation were significantly smaller.

Larger CSDs at G11Hα3 and the P12CδH2 have been observed previously for less stable Trp-cage species (and upon partial melting of stable Trp-cages); these were the basis for proposing a “half-cage” state4,5b,7b. Notably, highly truncated “half-cage” peptides terminated just beyond the G11 position displayed a tendency toward both helix formation and Gly11 docking against Trp6. These half-cage structures could be stabilized through an increase in helix-propensity, accomplished by lengthening of the helix, acetylation, and/or the addition of TFE. The most stable construct, Ac-DAAA-AAYAQWLADGG-NH2, was >70% folded in water at 280 K (>90% folded in TFE). In the case of Ac-DAAA-AAYAQWLADGGPASG (Tm » 25 °C), which also appears in Fig. 3, CSDs diagnostic of a half-cage state also appear for P12.

Although the numerous ring current shifts and sequence-remote NOEs within the hydrophobic core indicated similar topologies for the circularly permuted Trp-cages, we sought a direct NMR structural comparison. Adding other stabilizing mutations to cp-T2C3, afforded cp-T2C3b (RPPPSDUAAYAQWLADaGWAS, Tm = 67°C) which displayed (based on CSD comparisons) a fold population of χF » 0.93 at 280 K. NMR structure ensembles were calculated based exclusively on NOEs for cp-T2C3b and (P12W)-T2C16b. The comparison appears in Fig. 4. The structures are nearly identical with RMSDs of 0.49 and 0.75 Å, backbone and heavy atoms, over the shared residues and backbone.Coordinates for the optimized circularly-permuted and standard-topology Trp-cage miniproteins have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, with accession numbers 2m7c and 2m7d, respectively.

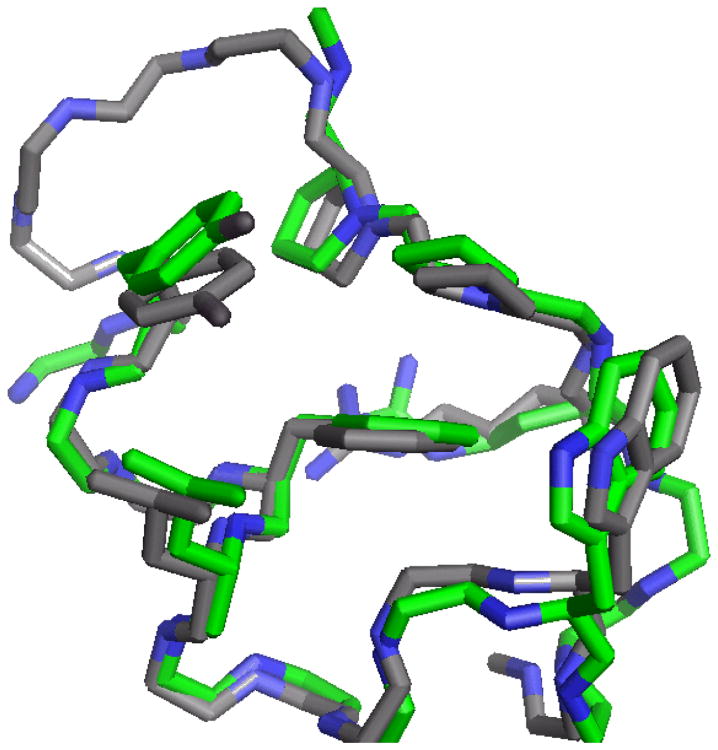

Fig. 4.

A comparison of representative structures from the NMR ensembles of [P12W]-T2C16b (green) and cp-T2C3b (gray). In the permutant, ring current shifts at W6, P17 and P18 due to the added Trp were in the same ratio as those observed in [P12W]-T2C16b indicating the same orientation. See the Supporting Information for complete ensembles (Figure S3), statistics and dihedral angles (Tables 2S,3S,4S)chemical shifts (Table 5S), NOE constraints and CSD comparisons (Tables 5S & 6S).

Conclusions

The formation, upon circular permutation, of the same hydrophobic core, evidenced by the usual set of long-range NOEs that define4,12 this folding motif, is clearly demonstrated and this was fully validated by a direct NMR structure comparison (Fig. 4). Chemical shift indicators of cage-structure formation (Fig. 3) indicate that the new termini of the circular permutants are somewhat frayed, with the greatest structural stability associated with the α helix and the capping interactions at each end of this unit. The stabilization of the N-terminus of the helix likely reflects the PSDUAAY sequence providing both the N-capping H-bonding interactions and the Pro/Tyr hydrophobic staple. For cyclo-TC1 with a PSGGDAY sequence over this span, additional i/i-4 H-bonds from A4-HN and Y3-HN to the loop Gly carbonyls were observed in the X-ray structure11; these are also suggested for cp-T2C3b based on both shift comparsions and the NMR ensemble. This can be seen in Fig. 4S and is corroborated by the observation that the dihedral angles in the connecting loop of cp-T2C3b conform to those observed in cyclo-TC1 (Table 4S).

The circularly permuted Trp-cage constructs display fold-stability increments (as ΔTm values, listed in the Supporting Information, Table S1) for pH changes, TFE addition, and for most single-site mutations examined that are similar to those of the non-permutated species. The destabilizing S14A mutation, however, was an outlier: ΔTm = -13 °C in the permutant, versus ΔTm = -35 °C in a non-permuted construct5b. This is attributed to the greater burial of this sidechain in the non-permuted constructs: the equivalent position in the circular permutant is S20, the C-terminal residue, which is located at the frayed end of a 310 helix. This suggests that the H-bonding network associated with the hydroxyl group of S14 in the complete Trp-cage fold5b,11 is not just a requirement for burial but also provides significant fold stabilization.

A Pro to Trp mutation (corresponding to P12W in the non-permuted topology) provided greater fold stabilization to the circular permutants, ΔTm = 18 °C for cp-T2C3b, (P19W)-cp-T2C2. In the case of cp-T2C3b, the net fold stabilization (ΔΔGU = 5.4 kJ/mol, ΔTm = 66 °C) versus cp-TC1 was greater than the sum (+3.9 kJ/mol) of the individual effects measured for the three stabilizing mutations: G10a, P12W, and the GGDA to DUAA loop change. Just as has been demonstrated5b for the original Trp-cage, a hydrophobic staple near the chain termini is a particularly fold stabilizing feature for miniproteins. In cp-T2C3b, the Trp/Pro interaction (W19/P2) provides this fold-rescuing feature. We anticipate that this will be a general feature and can be used for miniprotein design. In this regard, Trp/Pro, Trp/Aryl appear to be particularly good candidates.15

Circular permutation necessarily causes a dramatic shift in the contact order of the key interactions that stabilize the Trp-cage and this could change the dominant folding pathway. Multiple folding pathways likely exist for the Trp-cage. Indeed, this has been postulated17 as the basis for the rapid folding displayed by this system despite its proportionately high contact order. In the case of standard Trp-cage constructs, early Y3/P19 hydrophobic staple or D9/R16 salt-bridge formation could have either a fold accelerating or retarding effect depending on the conformation of remaining chain. In particular, early salt-bridge formation, with an incorrect placement of the indole ring has appeared as a kinetic trap in some MD folding simulations.9a,18 In the case of the cyclized structure, the early formation of either of these enthalpically favorable interactions should facilitate the completion of the folding pathway. For the circular permutant structures, D/R salt-bridge formation would appear to be precluded as an early step, even though it does appear to be a feature of the folded state.

As previously noted,11 cyclo-TC1 is the most stable Trp-cage construct reported to date; a cyclization-induced ΔΔGU ≥ 8 kJ/mol was observed. We posit that a protein fold is most likely to benefit from cyclization or circular permutation if this brings important interactions (the Y3/P19 hydrophobic staple in the present case) much closer in ‘sequential distance’; the Y3/P19 interactions can form and persist in early folding intermediates potentially improving access to alternate folding pathways. Cutting the cyclic Trp-cage construct supports this theory: the dominant folding path for the Trp-cage must necessarily be different in the circular permutant versus the standard Trp-cage, yet the structure is the same.The initial folding of the cyclic construct can follow both the alternate pathway of the circular permutant and (to a lesser extent) the standard topology folding pathway.

We expect that comparisons of the folding dynamics of cyclic Trp-cage constructs and the same sequences with cuts at different sites will elucidate the significance of the multiple predicted folding pathways for this miniprotein, as well as test the effects of contact order on folding rates in designed construct of minimized size. In our laboratory, the dynamics studies will employ multiple natural and exogenous site-specific probes, placed in both normal topology structures and circular permutants, with fluorescence-monitored T-jumps and dynamic linewidth NMR as the spectroscopic data for extracting folding and unfolding rates. The folding rate comparisons for permuted and non-permuted sequences of comparable thermodynamic stability are in progress; these should provide insights into the two different folding pathways that can provide the same structure.

The circular permutant structures reported herein, particularly cp-TC2c and cp-T2C3b, should provide a new testing arena for MD folding simulations. In support of the value of such studies we can note that Prof. Yuguang Mu [Nanyang Technology U., Singapore, pers. commun.] has performed preliminary MD folding simulations of circularly permuted sequences. The MD protocols and force-fields that provide the Trp-cage fold starting with the standard sequence8a, do not afford the cage structure as the dominant cluster of folded species in the case of the circular permutant sequences. The failure of Rosetta19 to predict the Trp-cage fold is another indication of current difficulties in computational folding schemes. We anticipate that subtle adjustments in the relative balance of vander Waals and Coulombic terms are required to correctly predict the folded states of smaller motifs and that these adjustment would also improve MD folding simulations for other proteins.

Experimental Methods

Peptide Synthesis and Purification

Linear peptides are synthesized on an Applied Biosystem 433A synthesizer employing standard Fmoc (9-fluorenyl methoxycarbonyl) solid-phase peptide synthesis methods and purified using RP-HPLC, using C18 and/or C8 stationary phases and a water(0.1% TFA)/acetonitrile(0.085% TFA) gradient as previously described.5b,20 The resins used for the synthesis were Wang resins preloaded with the C-terminal amino acid. C-terminal amides were prepared similarly but using Rink resins. Peptides were cleaved from the resin using a 95:2.5:2.5 trifluoroacetic acid (TFA): triisopropylsilane: water mixture. The sequences of all peptides were confirmed by the molecular ions observed using Bruker Esquire ion-trap mass spectrometry.

NMR Spectroscopy

Samples for 2D NMR spectral studies consisted of ∼1.5 mM peptide in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7, 10% D2O, with DSS as an internal chemical shift reference. NMR experiments were collected at 500, 700, 750, or 800 MHz on Bruker DRX and AV spectrometers. Full 1H spectral assignments were made by using a combination of 2D NOESY and TOCSY experiments. The HN and Hα chemical shifts deviations (CSD) were calculated using the CSDb algorithm21. In NMR melts, plots of CSD versus temperature are used to derive fold populations as previously presented5b,11,12,19,22.

CD spectroscopy

Stock solutions of approximately 200μM peptide concentration were prepared using 50 mM aqueous pH 7.0 phosphate buffer. Accurate concentrations were determined by UV spectroscopy assuming the standard molar absorptivities for the Trp and Tyr residues present. The samples were typically diluted to obtain circa 30 μM peptide solutions, with spectra recorded on a Jasco J720 spectropolarimeter using 0.10 cm pathlength cells over a UV range of 190-270 nm range as previously described.5b, 5c,12 In melting studies, temperatures ranged from 5 to 95 °C in 10° increments.

The folded fraction (χF) was determined by defining the temperature-dependent CD signal of the unfolded and folded states and assuming a linear χF relationship for signals between the two lines. The CD spectrum of the unfolded state, expected to be sequence independent, has been previously determined for several Trp-cage constructs in 7M Gdm+Cl: [θ]222 (deg-cm2/dmol-residue) = -750 - 27•T(°C).5b,11,12,20 We employed an unfolded baseline of [θ]U = -660 - 24•T(°C) for species containing D-Ala substitutions5c. Minor changes in the unfolded baseline values could result from the different residue substitutions23 in the present study. Since the reported24-25 sequence-dependent changes in the CD spectra of unfolded ensembles are predominantly at wavelengths far from the wavelength monitored in the present case and all of our residue substitutions are minor local changes, the differences in fraction unfolded values that might result were viewed as insignificant. In previous CD studies of Trp-cage species, folded baselines derived from the melts corresponded to a 0.30 – 0.34% loss of signal per °C: [θ]F = [θ]F,0°C - 0.0032•[θ]F,0°C•T(°C).5b,12 This relationship was confirmed by pre-melting slopes for hyperstable constructs that displayed, based on NMR shifts, less than 10% melting up to 320 K.

Circular Dichroism (CD) monitored melting

The analysis of the TC13a melts employed the previously determined 100% folded baseline for TC10b, [θ]F = [θ]F,0°C −0.0032• [θ]F,0°C • T(°C), with [θ]F,0°C = −18,612 deg-cm2/dmol-res. The best sigmoidal fit for cyclo-TC1 required: in aqueous buffer - [θ]F = [1 − 0.0030• T(°C)] • [θ]F,0°C , [θ]F,0°C = −20,730 deg-cm2/dmol-res; in 5M Gdm+Cl− - [θ]F = [1 − 0.0032• T(°C)] • [θ]F,0°C , [θ]F,0°C = −20,236 deg-cm2/dmol-res11. The ellipticity at the 222-223 nm minimum was monitored. The treatment of CD data for T2C13, and other Trp2-cage species, is complicated by the appearance of an exciton couplet (CD maximum at 228 nm and a minimum at 215-217 nm)15,16,21 due to mixing of indole/indole and/or indole/phenol transitions. The W/W exciton couplet of P12W mutants shifts the CD minimum of the Trp-cage to 217-219 nm. This shift is observed in both normal topology and circularly permuted Trp-cage species (Fig. 1S) and reflects a Trp/Trp exciton couplet with a maximum at 228 nm and a minimum at 213 nm; the latter serving to blue-shift the observed minimum from the standard α helical value. Difference spectra indicate that the exciton couplet is more intense in the non-permuted sequence while the helical signature is more intense in the permutant. The latter likely reflects a lesser degree of N-terminal helix fraying in the permutated sequence. We could extrapolate the 100%-folded value at 218 nm relying on NMR measures of fraction folded from 280 to 320K. This defines the temperature dependence of [θ]218 for T2C13 as [θ]F = [θ]F,0°C −0.29/100 • [θ]F,0°C•T, with [θ]F,0°C = −21000 deg-cm2/dmol-res. CD determined melting points are collected in Table 1S.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIH grant (GM099899) and an NIH traineeship to BLK (T32 GM008268). The 800 MHz NMR was supported by an instrumentation grant (1S10RR029217) from the NIH.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available

References

- 1.Lo WC, Lee CC, Lee CY, Lyu PC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn679. CPDB (Circular Permutation Data Base) is found under http://sarst.life.nthu.edu.tw/cpdb/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Camarero JA, Pavel J, Muir TW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:347. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980216)37:3<347::AID-ANIE347>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Camarero JA, Fushman D, Sato S, Giriat I, Cowburn D, Raleigh DP, Muir TW. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:1045. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhou HX. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9280. doi: 10.1021/ja0355978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kier B, Byrne A, Scian M, Anderson J, Andersen NH. Folding landscape exploration by circular permutation and capping β structures. In: Kokotos G, Constantinou V, Matsoukas J, editors. Peptides 2012, Proceeding of the 32ndEPS. 2012. pp. 70–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neidigh JW, Fesinmeyer RM, Andersen NH. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:425. doi: 10.1038/nsb798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Lin JC, Barua B, Andersen NH. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13679. doi: 10.1021/ja047265o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Barua B, Lin JC, Williams DV, Neidigh JW, Kummler P, Andersen NH. PEDS. 2008;21:171. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Williams DV, Barua B, Andersen NH. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:4287. doi: 10.1039/b814314e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Simmerling CL, Strockbine B, Roitberg AE. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11258. doi: 10.1021/ja0273851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Snow CD, Zagrovic B, Pande VS. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14548. doi: 10.1021/ja028604l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Searle MS, Ciani B. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:458. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mok KH, Kuhn LT, Goez M, Day IJ, Lin JC, Andersen NH, Hore PJ. Nature (London) 2007;447:106. doi: 10.1038/nature05728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Xu W, Mu Y. Biophys Chem. 2008;137:116. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Paschek D, Hempel S, Garcia AE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804775105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Day R, Paschek D, Garcia AE. Proteins. 2010;78:1889. doi: 10.1002/prot.22702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Hu Z, Tang Y, Wang H, Zhang X, Lei M. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;475:140. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Černý J, Vondrásek J, Hobza P. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:5657. doi: 10.1021/jp9004746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Marinelli F, Pietrucci F, Laio A, Piana S. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Juraszek J, Bolhuis PG. Biophys J. 2008;95:4246. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Beck DAC, White GWN, Daggett V. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:514. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Neuman RC, Gerig JT. Biopolymers. 2008;89:862. doi: 10.1002/bip.21028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wafer LNR, Streicher WW, Makhatadze GI. Prot Struct, Funct Bioinform. 2010;78:1376. doi: 10.1002/prot.22681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rovó P, Farkas V, Hegyi O, Szolomajer-Csikós O, Tóth K, Perczel A. J Pepide Sci. 2011;17:610. doi: 10.1002/psc.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rovó P, Stráner P, Láng A, Bartha I, Huszár K, Nyitray L, Perczel A. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:2628. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rodriguez-Granillo A, Annavarapu S, Zhang L, Koder RL, Nanda V. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18750. doi: 10.1021/ja205609c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Culik RM, Serrano AL, Bunagan MR, Gai F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:10884. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Culik RM, Annavarapu S, Nanda V, Gai F. Chemical Phys. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2013.01.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphys.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Scian M, Lin JC, Le Trong I, Makhatadze GI, Stenkamp RE, Andersen NH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121421109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DV, Byrne A, Stewart J, Andersen NH. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1143. doi: 10.1021/bi101555y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornton JM, Sibanda BL. J Mol Biol. 1983;167:443. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwai H, Plückthun A. FEBS Lett. 1999;459:166. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kier BL, Andersen NH. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14675. doi: 10.1021/ja804656h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bunagan MR, Yang X, Saven JG, Gai F. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:3759. doi: 10.1021/jp055288z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh K, Ozkan SB, Dill KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11920. doi: 10.1021/ja066785b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Zhou R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233312100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ding F, Buldyrev SV, Dokholyan NV. Biophysical Journal. 2005;88:147. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Linhananta A, Boer J, MacKay I. J Chem Phys. 2005;122:114901. doi: 10.1063/1.1874812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das R. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barua B. PhD Thesis. University of Washington; Seattle, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fesinmeyer RM, Hudson FM, Andersen NH. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7238. doi: 10.1021/ja0379520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J. PhD Thesis. University of Washington; Seattle, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi Z, Woody RW, Kallenbach NR. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;62:163. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dragomir I, Measey TJ, Hagarman AM, Schweitzer-Stenner R. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:13241. doi: 10.1021/jp0616260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagarman A, Mathieu D, Toal S, Measey TJ, Schwalbe H, Schweitzer-Stenner R. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:6789. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.