Abstract

Introduction:

The eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori following the standard triple therapy is declining. This study was conducted to test whether the addition of Lactobacillus reuteri to the standard triple therapy improves the eradication rates as well as the clinical and pathological aspects in H. pylori infection.

Methods:

A total of 70 treatment-naïve patients were randomly assigned into group A (the L. reuteri treated group) and group B (the placebo control group). Patients were treated by the standard triple therapy for 2 weeks and either L. reuteri or placebo for 4 weeks. They were examined by symptom questionnaire, H. pylori antigen in stool, upper endoscopy with biopsies for rapid urease test and histopathological examination before treatment and 4 weeks after treatment.

Results:

The eradication rate of H. pylori infection was 74.3% and 65.7% for both L. reuteri and placebo treated groups, respectively. There was a significant difference regarding the reported side effects, where patients treated with L. reuteri reported less diarrhea and taste disorders than placebo group. A significant difference within each group was observed after treatment regarding Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) scores; patients treated with L. reuteri showed more improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms than the placebo treated group. The severity and activity of H. pylori associated gastritis were reduced after 4 weeks of therapy in both groups. The L. reuteri treated group showed significant improvement compared with the placebo treated group.

Conclusion:

Triple therapy of H. pylori supplemented with L. reuteri increased eradication rate by 8.6%, improved the GSRS score, reduced the reported side effects and improved the histological features of H. pylori infection when compared with placebo-supplemented triple therapy.

Keywords: eradication rate, gastritis, Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale, Helicobacter pylori, Lactobacillus reuteri, triple therapy

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection is a widespread disease and is endemic in many countries, including Egypt [Hunt et al. 2011], with a wide range of morbidity that requires appropriate antimicrobial therapy [Vaira et al. 2001]. However, the eradication rate following the standard triple therapy is declining worldwide and this necessitates the introduction of new antimicrobial agents [De Francesco et al. 2004]. In view of the in vivo and in vitro activities against H. pylori, the use of different strains of probiotics in the treatment of H. pylori may be justifiable. Lactobacillus reuteri, through different mechanisms including production of reuterin, has anti-H. pylori activity and has been evaluated for improving the eradication rates of H. pylori [Hamilton-Miller, 2003] with contradictory results [Francavilla et al. 2008; Scaccianoce et al. 2008]. This study was conducted to assess whether the addition of L. reuteri to the standard triple therapy improves the eradication rate as well as the clinical and pathological aspects of H. pylori infection.

Patients and methods

Study design

We performed a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized prospective study.

Patients

All adult dyspeptic patients presented to the outpatient gastroenterology clinics of the Tropical Medicine and Internal Medicine Departments, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University Hospitals, Egypt, from June 2012 to February 2013 were offered to participate in the study. Patients who agreed gave written informed consent to participate in the study and to undergo all interventions needed. A total of 70 treatment naïve patients were enrolled and randomly assigned into two groups, group A (the L. reuteri treated group) and group B (the placebo control group).

Inclusion criteria

Patients with the following criteria were included:

age 18–60 years;

any sex;

confirmed H. pylori infection;

good mentality to understand aim, benefits and steps of the study;

assumed availability during the study period.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with the following conditions were excluded from the study:

chronic diseases, e.g. diabetes, renal failure and cirrhosis;

malignancies;

gall bladder disorders;

peptic ulcer;

prior upper digestive tract surgery;

prior probiotic therapy in the last month;

antibiotics, proton-pump inhibitors and H2 receptor blockers therapy within 1 month prior to commencement of study;

known allergy to the used medications.

Definitions

H. pylori infection is defined in this study as positivity to all these tests: H. pylori antigen in stool; histopathological confirmation of H. pylori bacilli; and rapid urease test.

H. pylori eradication is defined in this study as concomitant negativity to all previously positive tests 4 weeks after the end of therapy (6 weeks after the end of the standard triple therapy).

Endoscopic features for H. pylori: H. pylori induced gastritis was classified as antral or corpus predominant [Price and Misiewicz, 1991].

Histology: Histopathological analysis was performed by the pathologist author, who was blinded to the treatment arm and the time points of tissue sampling. All biopsies were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and giemsa stains. All biopsy specimens were evaluated for the presence of H. pylori bacilli, mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells and monocytes) as markers of inflammation and polymorphonuclear leucocytes (neutrophils) as markers of activity. Inflammation and activity were graded using a semi-quantitative score ranging from 0 (none), 1 (minimal), 2 (mild), 3 (moderate) to 4 (severe) [Price and Misiewicz, 1991; Stolte et al. 1995; Pantoflickova et al. 2003].

Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) [Svedlund et al. 1988]: All patients attended an interview for the recall of gastrointestinal symptoms. The 14-item GSRS to assess the severity and frequency of symptoms was reported. The following symptoms were specifically investigated: abdominal pain, acid regurgitation, heartburn, sucking sensation in the epigastrium, nausea and vomiting, borborygmus, abdominal distension, eructation, increased flatus, disorders of defecation [decreased/increased passage of stools, consistency of stools (loose/hard), urgency and feeling of incomplete evacuation]. Other symptoms investigated included inappetence, halitosis, taste disturbance, and urticaria.

Triple therapy associated diarrhea was defined according to the World Health Organization as three or more abnormally loose bowel movements per 24 hours and was graded as mild, moderate and severe by the patient himself in the symptom questionnaire [Johnston et al. 2008].

Patient assessment

All patients were subjected to the following assessments.

Full history-taking with symptom questionnaire.

Full clinical examination.

Abdominal ultrasound examination.

H. pylori antigen in stool (On Site H. pylori Ag Rapid Test, CTK BIOTECH, USA). This is a qualitative assessment of H. pylori antigens depending on the use of monoclonal antibodies against H. pylori conjugated with colloid gold. Positive cases were marked with two bands of color changes (one test band and one control band).

Upper digestive endoscopy with full comment on pathological lesions, biopsy and rapid urease test. The rapid urease test, a qualitative assessment of urease activity, was performed using fresh antral and corporal biopsies. Biopsies were impeded on the slides without any contaminating blood and results were classified as negative if no color change from the yellow color for 1 hour while sample with color change toward the pink color was considered positive (HelicotecUT-Plus, Strong Biotech Corporation, Taiwan).

Histopathological examination of the gastric biopsies (hematoxylin and eosin and giemsa stains) for determining the presence of H. pylori bacilli, presence and density of inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils.

Recording of GSRS at baseline and 4 weeks after completion of therapy. Reporting of the side effects by symptom questionnaire at weeks 1, 2, 3 and 4 of therapy.

Four weeks after therapy, re-examination was carried out by H. pylori antigen in stool and re-endoscopy for pathological lesions, biopsies and rapid urease test.

Patient management

Group A

Received triple therapy [omeprazole 20 mg twice a day (bid), amoxicillin 1000 mg bid, clarithromycin 500 mg bid] and L. reuteri [a mixture of L. reuteri DSM 17938 and L. reuteri ATCC PTA 6475, delivered in a dose of 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) of each strain in a chewable tablet for a total dose of 2 × 108 CFU/day] for 2 weeks followed by L. reuteri alone for another 2 weeks (i.e. L. reuteri was given for 4 weeks) [Francavilla et al. 2008].

Group B

Received the same triple therapy plus a placebo for 2 weeks followed by placebo alone for another 2 weeks. The appearance and taste of the placebo study product were identical to the active study product.

Randomization and blinding

This was carried out by an independent physician using a computer generated system. He also carried out the task of blinding (patient and investigator) using a computer generated randomization list. The independent physician enrolled participants and assigned participants to the interventions.

Outcomes

Primary end point

The primary end point was eradication of H. pylori infection 4 weeks after completion of therapy.

Secondary end point

The secondary end point was the development of severe adverse effects to the used medications and dietary supplements.

Statistical analysis

Sample size

A total of 70 patients were included with 35 in each arm. The sample size was calculated assuming eradication of H. pylori in at least 70% of treated patients [Hunt et al. 2011], aiming to detect a difference of 30% based on a 0.80 power to detect significant difference (p = 0.05, two-sided).

Data were checked, entered and analyzed using SPSS version 16 for data processing and statistics. Data were expressed as number and percentage for qualitative variables and mean ± standard deviation (SD) for quantitative ones. A p value <0.05 indicates significant results. Comparison between the two groups was done using t test and Chi square tests, while the paired t test was used to assess variability within the same group before and after therapy.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt (ZU-IRB # 395/29-4-2012) [Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01593592]. All patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study and for performing all relevant interventions.

Results

Trial flow

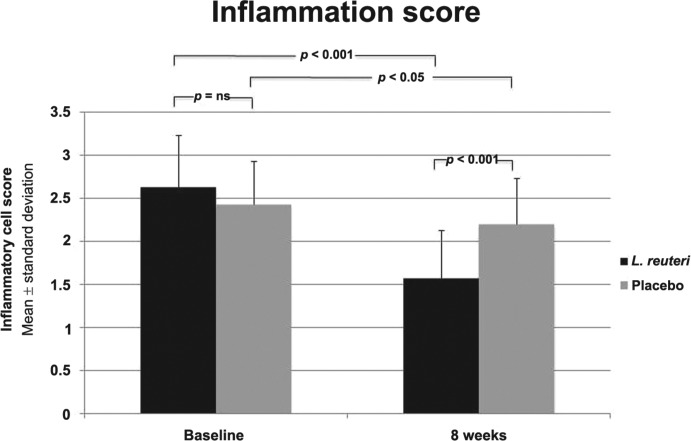

Out of 213 patients presented to the outpatient gastroenterology clinics during the study period, 70 patients were included. A total of 119 patients were excluded according to our criteria; 94 patients met the inclusion criteria but 24 patients refused to be re-endoscoped and hence were also excluded (Figure 1). There were no dropouts and all subjects remained in the study until the end, and were fully compliant according to the regular interviews. Confirmation of pill intake was recorded by pill count and patients were instructed to bring the vials even when empty. At each visit patients were given a total number of pills sufficient for the period until the next interview. Overall the compliance was good and more than 98% of the chewable tablets were consumed.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. Out of 213 patients, 94 patients met the inclusion criteria of whom 70 were randomly assigned to the L. reuteri and placebo groups.

HpSA, H. pylori stool antigen; RUT, rapid urease test; Endo, endoscopic; histo, histopathological confirmation; GSRS, Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale; Ome, omeprazole; Amox, amoxicillin; Clarith, clarithromycin; bid, twice daily; w, week.

Study patients

A total of 70 subjects with confirmed H. pylori infection, of which 61.3% were females and 38.7% were males, with a mean age of 35.00 ± 12.65 years (range 18–60 years) participated in the study. They were randomized into two study arms: 35 patients in the L. reuteri group (group A) and 35 patients in the placebo group (group B). Most of our patients were of rural residence (68.6%) and nonsmokers (90%). The two treatment groups were similar in their demographic, clinical and endoscopic characteristics at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the two groups.

| Group A | Group B | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 33.20 ± 13.974 | 36.80 ± 11.085 | 0.237 |

| Range | (18–60) | (22–60) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 13 (37.1%) | 11 (31.4%) | 0.615 |

| Female | 22 (62.9) | 24 (68.6%) | |

| Residence | |||

| Rural | 22 | 26 | 0.303 |

| Urban | 13 | 9 | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 4 | 3 | 0.690 |

| No | 31 | 32 | |

| Endoscopic pattern of gastritis | |||

| Antral predominant | 31 | 31 | 1.00 |

| Corpus predominant | 4 | 4 | |

SD, standard deviation.

Endoscopic features

All patients had gastritis at the time of first endoscopy. Antral predominant gastritis and corpus predominant gastritis were encountered in 88.6% and 11.4% of patients in the L. reuteri group and in the placebo group respectively. At the end of therapy there was no change in the distribution of gastritis (p = 1.0) (Table 1).

H. pylori eradication

After the probiotic/placebo supplementation, the overall eradication rate of the H. pylori infection was 70% (49/70), distributed as 74.3% (26/35) and 65.7% (23/35) for the L. reuteri and placebo groups respectively. Although the eradication rate was higher in the L. reuteri treated group by 8.6%, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.603).

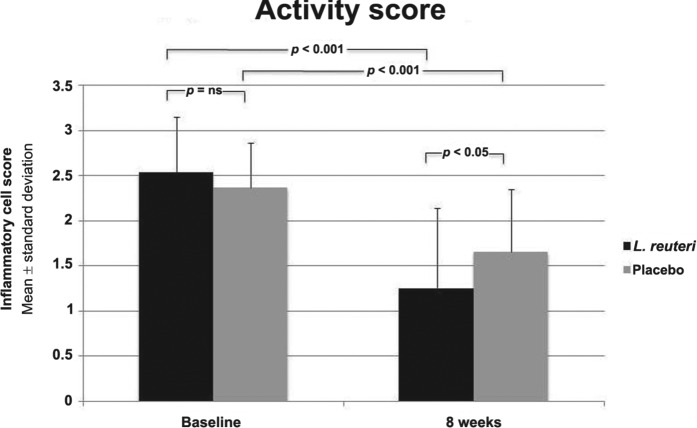

Gastrointestinal symptoms

The baseline GSRS scores for both the L. reuteri group and placebo group were 14.42 ± 4.745 and 16.34 ± 4.869 respectively (Figure 2) with no significant difference (p = 0.052).

Figure 2.

Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) values between both groups at baseline and 8 weeks later and between each group before and 4 weeks after end of treatment.

ns, not significant.

After treatment (8 weeks from the baseline), GSRS scores for both L. reuteri group and placebo group were 4.77 ± 2.446 and 9.06 ± 5.291 respectively (Figure 2); patients treated with L. reuteri showed more improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms (p < 0.001).

In patients receiving triple therapy for 2 weeks plus L. reuteri for 4 weeks, we observed a significant decrease of GSRS 8 weeks from the baseline compared with the pretreatment value [14.42 ± 4.745 versus 4.77 ± 2.446; 95% confidence interval (CI) of the difference: 8.380–10.911; p < 0.001] (Figure 2). The same was also noticed in those receiving triple therapy plus placebo [16.34 ± 4.869 versus 9.06 ± 5.291; 95%CI of the difference: 5.409–9.163; p < 0.001] (Figure 2). We found a difference in the number of patients who reported a decrease of the GSRS although it was not statistically significant (35/35 in L. reuteri group; 30/35 in placebo group, p = 0.054).

When the frequencies of the symptoms were evaluated, we found that patients receiving L. reuteri showed marked improvement of these symptoms, epigastric pain, sucking sensation in the epigastrium and eructation.

Both study products were well tolerated by all subjects and no serious adverse events were reported during the period of intake. The types of adverse events reported in this study did not differ significantly between the two groups.

The most common side effects were diarrhea, taste disorders and distension (Table 2). There was a significant difference between the two groups concerning the reported side effects; patients treated with L. reuteri reported less diarrhea and taste disorders than placebo group (p = 0.002). All reported side effects were rather mild and there was no reported treatment discontinuation because of the side effects.

Table 2.

Reported side effects in the two groups during the 4 weeks of therapy.

| Group A | Group B | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taste disorders | 2 | 8 | 0.002 |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 10 | |

| Distension | 5 | 4 | |

| Vomiting | 2 | 2 |

Pathological lesions

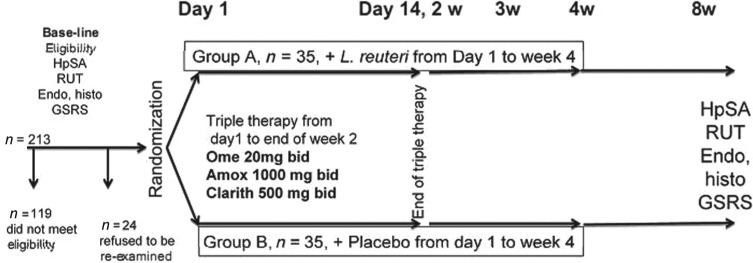

Inflammation

The severity of H. pylori associated gastritis was reduced after 8 weeks from the beginning of therapy in the L. reuteri treated group compared with pretreatment period (inflammatory cell score 2.63 ± 0.598 versus 1.57 ± 0.558; p < 0.001). The severity of H. pylori associated gastritis was also reduced after 8 weeks from the beginning of therapy in the placebo treated group compared with pretreatment period (inflammatory cell score 2.43 ± 0.502 versus 2.20 ± .531; p = 0.019). The L. reuteri treated group showed more improvement in the inflammatory cell score than placebo treated group (p < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Inflammatory cell score (lymphocytes, plasma cells) between both groups at baseline and 8 weeks later and between each group before and 4 weeks after end of treatment.

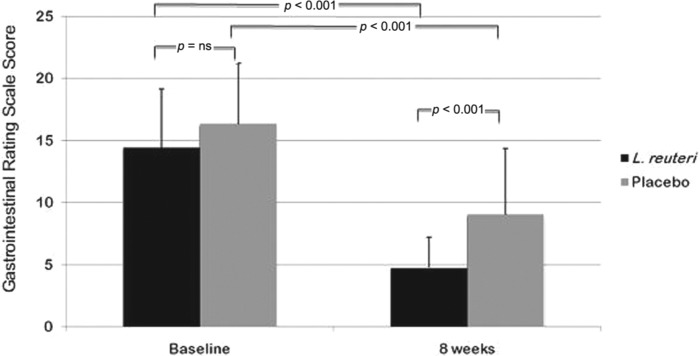

Activity

The activity of H. pylori associated gastritis was reduced after 8 weeks from the beginning of therapy in L. reuteri treated group as compared to the pretreatment period (inflammatory cell score 2.54 ± 0.611 versus 1.26 ± 0.886; p < 0.001). The activity of H. pylori associated gastritis was reduced after 8 weeks from the beginning of therapy in the placebo treated group compared with pretreatment period (inflammatory cell score 2.37 ± 0.490 versus 1.66 ± 0.691; p < 0.001). The L. reuteri showed more improvements in the inflammatory cell score than the placebo treated group (p = 0.034) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Inflammatory cell score (neutrophils) between both groups at baseline and 8 weeks later and between each group before and 4 weeks after end of treatment.

Discussion

Treatment of H. pylori infection is becoming a very relevant problem, especially in the developing countries. Although different therapeutic regimens are currently available, treatment failure remains a growing problem in daily medical practice. Several factors could play a role in the eradication failure, but the most relevant are antibiotic resistance and patient’s compliance [Ibrahim et al. 2012].

The overall eradication rate reported in this study is 70%, which lies between different eradication rates ranging from 60% [Yaşar et al. 2010] to 94.4% [Manfredi et al. 2012] either with the standard triple therapy or when the sequential therapy is used. The eradication rate increased when probiotics were added to the triple therapy; in our study the eradication rate increased to 74.3%. Different rates were reported from different studies and this may point to a strain specific anti-H. pylori activity. For L. reuteri, different eradication rates were reported ranging from 53% to 88% [Lionetti et al. 2006; Francavilla et al. 2008; Scaccianoce et al. 2008; Ojetti et al. 2012].

Resistant strains of H. pylori are now widely prevalent in the west, and the eradication rate with current regimens fails in 10% to 20% of patients [Vakil et al. 1998; Mégraud et al. 2013].

The 30% failure rate in this study could be attributed to the growing antimicrobial resistance, although it was not examined in the current study. Several investigators have documented a high response rate of H. pylori isolates to amoxicillin [Mégraud and Lehours, 2007; Seck et al. 2009], others reported variable resistance rates ranging from 18.5% to 100% [Godoy et al. 2003; Thyagarajan et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2006; Abordin et al. 2007]. In our community resistance to amoxicillin have been recently reported to be 3.7% [Ibrahim et al. 2012].

In our rural communities, the prevalent populations in this study, we expect higher rates of amoxicillin resistance because this antibiotic is widely available in primary care units and is used for different sorts of infection in particular respiratory tract infections. In addition, this antibiotic has been available for a long time and widely abused in self medication, a common custom in the Egyptian rural community.

Resistance to clarithromycin is becoming more prevalent in some European countries, where the prevalence may be as high as 17% [Romano and Cuomo, 2004; Mégraud et al. 2013]. Clarithromycin resistance in H. pylori infection has sharply decreased the success of eradication by 40% to 50% [Njume et al. 2009]. Also a growing clarithromycin resistance has been reported in the Egyptian population; a recent H. pylori study reported the rate of resistance to be 11.1% in gastric isolates and 27% in dental isolates [Ibrahim et al. 2012].

An important issue in the eradication of H. pylori is patient compliance, which is largely affected by side effects related to the triple therapy used [Njume et al. 2009]. Addition of L. reuteri to the triple therapy reduced the frequency of side effects, particularly diarrhea; this should improve patient compliance and adherence to therapy. Similar results were reported from different studies that used L. reuteri as adjuvant to the triple therapy in H. pylori eradication [Francavilla et al. 2008; Scaccianoce et al. 2008; Efrati et al. 2012; Ojetti et al. 2012]. Although all patients in the present study were compliant with the regimen prescribed, in daily clinical practice reduced side effects would increase the patients’ compliance especially with retreat patients who experienced side effects with previous triple therapies and therefore were not motivated to be retreated due to intolerable side effects.

The reported side effects in this study are not different from side effects reported in other studies [Francavilla et al. 2008; Scaccianoce et al. 2008] and all were self limited after therapy. No serious adverse events were reported; furthermore no manifestations related to systemic invasion of L. reuteri were reported, confirming safety issues in the use of these strains in H. pylori treatment.

Improvement of clinical manifestations is a marker of successful therapy; both groups showed improvements in the GSRS after therapy, but the L. reuteri group showed more. These improvements of symptoms should advocate patients for more compliance and adhesion to therapy. Improvement was greater in symptoms related to the fore gut including epigastric pain, sucking sensation in the epigastrium, and eructation which support the conclusion that H. pylori eradication is the direct cause for symptom amelioration.

Another important issue in H. pylori infection is gastritis in terms of pathological features. In this study an improvement of gastritis inflammatory score as well as activity was noted. Improvement of the histological features in H. pylori infection is not a novel finding of this study as many investigators have noticed improvement of gastric antral activity with the use of different probiotic preparations and strains [Felley et al. 2001; Pantoflickova et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2004]. The novel finding in our study is that L. reuteri also has an impact on the H. pylori histopathological features, a valuable effect added to its clinical aspects and improvement in eradication rate confirmed in this study and other studies [Lionetti et al. 2006; Francavilla et al. 2008; Scaccianoce et al. 2008]. This would certainly reduce the risk of atrophic gastritis and gastric malignancies related to H. pylori in the long term.

Several mechanisms could contribute to an improvement of H. pylori associated gastric inflammation and activity by the use of probiotics. First, probiotic therapy may reinforce gut innate defenses. In the gastric mucosa, H. pylori may interact with epithelial cells through secretory components or as a result of adherence [Chauviere et al. 1992]. Second, some strains may prevent H. pylori adherence by increasing mucin expression [Mack et al. 1999] that is usually downregulated in H. pylori infection [Byrd et al. 2000]. Third, probiotics could secrete antibacterial substances. It has been suggested that the antibacterial activity of the L. reuteri is related to an antimicrobial substance called reuterin which has bactericidal and bacteriostatic activities against a number of gram positive and negative bacteria and even some fungi [Hamilton-Miller, 2003; Spinler et al. 2008]. Fourth, some strains of probiotics are known to have anti-inflammatory activity (e.g. the L. reuteri ATCC PTA 6475 that was used in this study was proved to suppress local pro-inflammatory cytokines production) [Thomas et al. 2012]. Finally, Lactobacilli may exert its favorable effect on the gastric mucosa through local or systemic immunomodulation [Cunningham-Rundles et al. 2000; Gill et al. 2000; Vitini et al. 2000]. Lactic acid bacteria may strengthen the gastric immunologic barrier through stimulation of local immunoglobulin A responses and alleviation of inflammatory responses, thus leading to a mucosa-stabilizing effect [Cunningham-Rundles et al. 2000].

Although improvements in H. pylori induced gastritis were noticed with different antibiotics used in H. pylori eradication in this study and also in previous studies [Marshall et al. 1987; Graham et al. 1993], probiotics associated improvements in the histopathological changes have particular importance due to various aspects. The effect is long lasting compared with the relatively short effect of antibiotics [Pantoflickova et al. 2003] and this may be due to its impact on the gut barriers and immunity [Vitini et al. 2000]. In addition, it is associated with higher eradication rate [Manfredi et al. 2012] and probably low recurrence rates. Finally, it is not associated with more side effects; in contrast, marked symptom improvements were noticed [Francavilla et al. 2008].

In conclusion, eradication triple therapy of H. pylori supplemented by L. reuteri increased the eradication rate by 8.6% (nonsignificant), improved the GSRS score (significant), reduced the side effects (significant) and improved the histological features (significant) in H. pylori infection compared with triple therapy supplemented with placebo.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all colleagues who helped conducting this study.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Contributor Information

Mohamed H. Emara, Tropical Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Al-Kornish Street, Zagazig 44519, Egypt

Salem Y. Mohamed, Internal Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt

Hesham R. Abdel-Aziz, Pathology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt

References

- Abordin O., Abdu A., Odetoyin B., Okeke I., Lawal O., Ndububa D., et al. (2007) Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori from patients in Ile-Ife, South-west, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 7: 143–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd J., Yunker C., Xu Q., Sternberg L., Bresalier R. (2000) Inhibition of gastric mucin synthesis by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 118: 1072–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauviere G., Coconnier M., Kerneis S., Fourniat J., Servin A. (1992) Adhesion of human Lactobacillus acidophilus strain LB to human enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells. J Gen Microbiol 138: 1689–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham-Rundles S., Ahrne S, Bengmark S., Johann-Liang R., Marshall F., Metakis L., et al. (2000) Probiotics and immune response. Am J Gastroenterol 95: S22–S25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco V., Zullo A., Hassan C., Della Valle N., Pietrini L., Minenna M., et al. (2004) The prolongation of triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori does not allow reaching therapeutic outcome of sequential scheme: a prospective, randomized study. Dig Liver Dis 36: 322–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efrati C., Nicolini G., Cannaviello C., Piazza O’Sed N., Valabrega S. (2012) Helicobacter pylori eradication: sequential therapy and Lactobacillus reuteri supplementation. World J Gastroenterol 18: 6250–6254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felley C., Corthésy-Theulaz I., Rivero J., Sipponen P., Kaufmann M., Bauerfeind P., et al. (2001) Favourable effect of an acidified milk (LC-1.) on Helicobacter pylori gastritis in man, Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 13: 25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla R., Lionetti E., Castellaneta S., Magistà A., Maurogiovanni G., Bucci N., et al. (2008) Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori infection in humans by Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 and effect on eradication therapy: a pilot study. Helicobacter 13: 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill H., Rutherfurd K., Prasad J., Gopal P. (2000) Enhancement of natural and acquired immunity by Lactobacillus rhamnosus (HN001), Lactobacillus acidophilus (HN017) and Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019). Br J Nutr 83: 167–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy A., Ribeiro M., Benvengo Y., Vitiello L., Miranda Mde C., Mendonça S., et al. (2003) Analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility and virulence factors in Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. BMC Gastroenterol 3: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D., Opekun A., Klein P. (1993) Clarithromycin for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Gastroenterol 16: 292–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton-Miller J. (2003) The role of probiotics in the treatment and prevention of Helicobacter pylori infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents 22: 360–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R., Xiao S., Megraud F., Leon-Barua R., Bazzoli F., Van Der Merwe S., et al. (2011) Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 20: 299–304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim N., Gomaa A., Abu-Sief M., Hifnawy T., Tohamy M. (2012) The use of different laboratory methods in diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection; a comparative study Life Sci J 9: 249–259 [Google Scholar]

- Johnston B., Supina A., Ospina M., Vohra S. (2008) Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Evid.-Based Child Health 3: 280–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim J., Kim N., Kim S., Jung H., Song I. (2006) Comparison of primary and secondary antimicrobial minimum inhibitory concentrations for Helicobacter pylori isolated from Korean patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents 28: 6–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti E., Miniello V., Castellaneta S., Magistá A., de Canio A., Maurogiovanni G., et al. (2006) Lactobacillus reuteri therapy to reduce side-effects during anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment in children: a randomized placebo controlled trial, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 24: 1461–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack D., Michail S., Wei S., McDougall L., Hollingsworth M. (1999) Probiotics inhibit enteropathogenic E. coli adherence in vitro by inducing intestinal mucin gene expression. Am J Physiol 276: G941–G950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi M., Bizzarri B., Sacchero R., Maccari S., Calabrese L., Fabbian F., et al. (2012) Helicobacter pylori infection in clinical practice: probiotics and a combination of probiotics + lactoferrin improve compliance, but not eradication, in sequential therapy. Helicobacter 17: 254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall B., Armstrong J., Francis G., Nokes N., Wee S. (1987) Antibacterial action of bismuth in relation to Campylobacter pyloridis colonization and gastritis. Digestion 37: 16–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mégraud F., Coenen S., Versporten A., Kist M., Lopez-Brea M., Hirschl A., et al. (2013) Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe and its relationship to antibiotic consumption. Gut 62: 34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mégraud F., Lehours P. (2007) Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Rev 20: 280–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njume C., Afolayan A., Ndip R. (2009) An overview of antimicrobial resistance and the future of medicinal plants in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol 3: 685–699 [Google Scholar]

- Ojetti V., Bruno G., Ainora M., Gigante G., Rizzo G., Roccarina D., et al. (2012) Impact of Lactobacillus reuteri supplementation on anti-Helicobacter pylori levofloxacin-based second-line therapy. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012: 1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoflickova D., Corthesy-Theulaz I., Dorta G., Stolte M., Isler P., Rochat F., et al. (2003) Favorable effect of long-term intake of fermented milk containing Lactobacillus johnsonii on H. pylori associated gastritis, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 18: 805–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A., Misiewicz J. (1991) Sydney classification for gastritis. Lancet 337: 174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M., Cuomo A. (2004) Eradication of H. pylori: a clinical update. MedGenMed 6: 19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaccianoce G., Zullo A., Hassan C., Gentili F., Cristofari F., Cardinale V., et al. (2008) Triple therapies plus different probiotics for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 12: 251–256 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seck A., Mbengue M., Gassama-Sow A., Diouf L., Ka M., Boye C. (2009) Antibiotic susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori isolates in Dakar, Senegal. J Infect Developing Countries 3: 137–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinler J., Taweechotipatr M., Rognerud C., Ou C., Tumwasorn S., Versalovic J. (2008) Human-derived probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri demonstrate antimicrobial activities targeting diverse enteric bacterial pathogens. Anaerobe 14: 166–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolte M., Batz C., Bayerdorffer E., Eidt S. (1995) Helicobacter pylori eradication in the treatment and differential diagnosis of giant folds in the corpus and fundus of the stomach. Z Gastroenterol 33: 198–201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svedlund J., Sjodin I., Dotevall G. (1988) GSRS: a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci 33: 129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C., Hong T., van Pijkeren J., Hemarajata P., Trinh D., Hu W., et al. (2012) Histamine derived from probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri suppresses TNF via modulation of PKA and ERK signaling. PLoS One 7: e31951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyagarajan S., Ray P., Das B., Ayyagari A., Khan A., Dharmalingam S., et al. (2003) Geographical difference in antimicrobial resistance pattern of Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates from Indian patients: multicentric study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 18: 1373–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaira D., Gatta L., Ricci C., D’anna L., Miglioli M. (2001) Helicobacter pylori: diseases, tests and treatment. Dig Liver Dis 33: 788–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakil N., Hahn B., Mc Sorley D. (1998) Clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori in patients with duodenal ulcer in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 93: 1432–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitini E., Alvarez S., Medina M., Medici M., de Budeguer M., Perdigon G. (2000) Gut mucosal immunostimulation by lactic acid bacteria. Biocell 24: 223–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Li S., Liu C., Perng D., Su Y., Wu D., et al. (2004) Effects of ingesting Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium-containing yoghurt in subjects with colonized Helicobacter pylori, Am J Clin Nutr 80: 737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaşar B., Abut E., Kayadıb H., Toros B., Sezıkl M., Akkan Z., et al. (2010) Efficacy of probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Turk J Gastroenterol 21: 212–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]