Abstract

Until recently, little attention has been paid to the existence of kin structure in the sea, despite the fact that many marine organisms are sessile or sedentary. This lack of attention to kin structure, and its impacts on social evolution, historically stems from the pervasive assumption that the dispersal of gametes and larvae is almost always sufficient to prevent any persistent associations of closely related offspring or adults. However, growing evidence, both theoretical and empirical, casts doubt on the generality of this assumption, not only in species with limited dispersal, but also in species with long dispersive phases. Moreover, many marine organisms either internally brood their progeny or package them in nurseries, both of which provide ample opportunities for kinship to influence the nature and outcomes of social interactions among family members. As the evidence for kin structure within marine populations mounts, it follows that kin selection may play a far greater role in the evolution of both behaviours and life histories of marine organisms than is presently appreciated.

Keywords: kin structure, social behaviour, cooperation, marine organisms, relatedness

1. Introduction

Ever since Hamilton [1] showed that cooperative behaviours should evolve whenever the relatedness-weighted benefit of the behaviour to the recipient is greater than the cost to the donor, it has been clear that a potentially dominant facet of the social environment is the relatedness of interactors. In his seminal paper, Hamilton [1] proposed that kin-selected cooperation was most likely to evolve in kin-structured populations, so that research into the evolution of cooperation via kin selection has largely focused on interacting individuals that live in more or less discrete groups. Over the past four decades, the main empirical examples of kin selection have thus arisen from studies of social insects and the cooperative breeding systems of terrestrial vertebrates [2,3].

2. Kin structure in the sea

In the marine realm, the effects of population structure and kinship on the evolution of social behaviours have largely been ignored. This is presumably because many marine organisms have biphasic life cycles, in which sessile or sedentary adults produce motile propagules (gametes, zygotes, spores or larvae) with apparently sufficient dispersal potential that repeated interactions involving kin, and hence the evolution of complex social behaviours, seem improbable (for a notable exception, see the discovery of eusociality in sponge-dwelling snapping shrimp [4]).

Yet, at some point in their life cycles, many sessile and sedentary marine organisms exhibit conditional social behaviours, ranging from potentially cooperative behaviours such as preferential settlement of larvae with conspecifics, and perhaps even kin [5,6], to clearly selfish behaviours such as intergenotypic fusion and aggression in colonial and clonal animals and algae [7–9]. For example, in numerous sponges, cnidarians, bryozoans and colonial ascidians, intraspecific competitive interactions span the range from no apparent response, through active cytotoxic rejection, to intergenotypic fusion [8,10,11]. Among cnidarians and some bryozoans, incompatibility responses extend beyond simple rejection, often eliciting a complex suite of agonistic behaviours [12,13].

3. Relatedness and social behaviours

As with the many social insects and vertebrates that modify the expression of their social behaviours according to the relatedness of conspecifics [14], a growing number of field and laboratory studies on clonal marine invertebrates show that rejection, aggression and fusion occur non-randomly with respect to the genotypes of interacting conspecifics: interactions between clonemates and close kin generally do not elicit cytotoxicity or aggression, whereas interactions between more distant relatives do [10,13,15]. Likewise, somatic fusion usually occurs only between clonemates and close kin.

Is the existence of such allorecognition systems consistent with kin recognition, or are these systems merely self/non-self-recognition adaptations that evolved to allow fusion as clonal organisms fragment, grow and then re-encounter self? Kin fusion (or non-aggression) in such instances would then largely reflect recognition errors (sensu [16]), rather than specific adaptations [17]. In most terrestrial systems, especially where dispersal is likely to occur over multiple spatial scales, individuals are likely to encounter both close and distant kin, and discrimination often has obvious selective advantages. In the sea, especially if most propagules have sufficient dispersal potential such that kin associations are likely to be rare, then it is less clear how selection would favour discrimination. However, in the above-mentioned cases, limited dispersal of sexual and asexual propagules [18], characteristic of many of clonal and even some aclonal marine organisms, coupled with the capacity for indeterminate growth and reproduction [19], intensify the likelihood of interactions between close relatives [15] (figure 1).

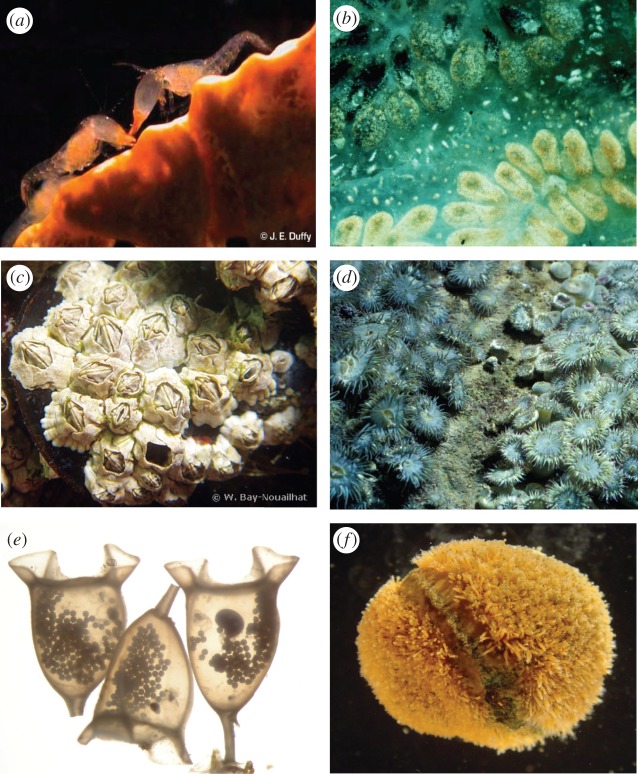

Figure 1.

Social interactions in the sea. (a) Encounter between eusocial snapping shrimp, Synalpheus regalis (photograph by J. E. Duffy); (b) Fusing colonies of the ascidian, Botryllus schlosseri (photograph by R. K. Grosberg); (c) an aggregation of barnacles, Semibalanus balanoides (photograph by Wilfried Bay-Nouailhat); (d) aggression border and fighting between clones of the sea anemone, Anthopleura elegantissima (photograph by D. J. Ayre); (e) embryos and trophic eggs within egg capsules of the whelk Solenosteira macrospira (photograph by Brenda Cameron); and (f) interclonal border separating two colonies of the hydroid, Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus inhabiting the shell of a hermit crab (photograph by R. K. Grosberg). (Online version in colour.)

4. Relatedness and group performance

Kin structure may also have other impacts beyond the regulation of intergenotypic fusion and aggression. For example, in the bryozoan Bugula neritina, individuals reared in genetically diverse aggregations grow faster, survive better and have higher fecundity than individuals settled in lower genetic diversity aggregations [20]. These positive effects of genetic diversity also crossed generations, with individuals in ‘unrelated mixtures’ producing larger offspring than individuals reared with siblings. The range of diversity that elicits such responses may be quite small: studies in marine invertebrates have shown that, as with terrestrial plants, even seemingly small genetic differences (i.e. full- versus half-sibs) can have large effects on performance of both juveniles and adults [20,21]. Thus, differences in kin structure among populations can have pervasive effects on population productivity within remarkably short periods of time. For example, in the seagrass Zostera marina, the degree of relatedness among interacting shoots varies significantly in natural populations: these differences in relatedness correspond to significant differences in the amount of plant biomass accumulation [22,23]. The mechanisms underlying this pattern remain unclear; however, the data support a role for cooperation among kin. Several vascular plants, for example, reduce below-ground investment in response to the presence of related individuals, leading to increased allocation to above-ground productivity [24]. Many habitat-forming species, such as seagrasses and mangroves, interact intensely with conspecifics of varying relatedness; thus, kinship could profoundly influence the functioning of ecosystems dominated by such species.

5. Dispersal and kin structure

Although it seems obvious that kin associations in the sea should be restricted to species with limited dispersal, several recent studies using high-resolution genetic markers, as well as a new generation of biophysical models [25], indicate that even species with extensive dispersal potential can self-recruit [26,27] and exhibit kin structure over scales of metres down to centimetres [28,29]. The reasons for this are just beginning to be understood, and include gregarious larval behaviour [30], consistent habitat preferences, variable recruitment events [31] and physical transport processes [28], all of which can promote the formation of dense conspecific aggregations (figure 1). For example, recent genetic analyses in the California spiny lobster (Panulirus interruptus) revealed significant kin structuring at several sites across their range, suggesting that these lobsters have substantial localized recruitment or maintain planktonic larval cohesiveness whereby siblings more likely settle together than disperse across sites [32].

6. Marine life histories and the opportunity for kin selection

Differences in dispersal aside, several features of the reproductive and developmental modes of marine organisms also provide many opportunities for kinship to play a role in the evolution of behaviour and life histories [33]. In organisms that internally or externally brood or encapsulate their offspring, close relatives may be compelled to interact. Indeed, encapsulation engenders some of the most extreme forms of parent–offspring conflict and sibling rivalry, including consumption of non-developing nurse eggs (oophagy) and of viable siblings (adelphophagy) [34]. Siblings not only compete for nutrients provided by their parents, but also for resources that are affected by the packaging per se, such as the availability of oxygen [35,36]. The ubiquity of egg masses, capsules and other forms of encapsulation in marine invertebrates suggests that competition among siblings occurs frequently. For example, females of the marine whelk Solenosteira macrospira are highly promiscuous, mating with an average of 13 males within a season [37]. Rates of cannibalism and consequently growth within a capsule also vary across a season, resulting in substantial differences in the size and number of emerging hatchlings [38]. In clutches laid later in the reproductive season, fewer embryos emerge at a larger size, and levels of intracapsular cannibalism are considerably higher than in clutches laid earlier on. Decreased relatedness of siblings within capsules, caused by higher levels of multiple mating later in the season, may drive this pattern.

Previous studies in invertebrates and fishes have documented that lower relatedness among siblings can actually increase embryo survival, presumably because genetic variation among siblings reduces competition for resources [21,39]. On the other hand, recent work in the brooding sea anemone Urticina felina shows that fusion among siblings occurs among brooded embryos and that the development of these megalarvae represents a form of kin cooperation conferring a size-related fitness advantage [40]. Occurrences of megalarvae were common in the populations studied, contradicting earlier reports of infrequent fusion in this species [41] and strengthening the case for an allorecognition system favouring fusion with kin rather than solely fusion with self [17].

7. Conclusion and future directions

It now appears that fine-scale genetic structure on scales from centimetres to metres characterizes many marine populations, even species with extensive dispersal potential, and even when populations appear to be genetically homogeneous over much broader spatial scales. Recent studies on marine organisms further show that the relatedness of interacting conspecifics can strongly affect many crucial aspects of performance across all levels of biological organization. Nevertheless, remarkably few studies in marine systems have characterized genetic structure on the scales relevant to ecological interactions, much less the links between the processes that generate social environments, and the impacts of the social environment on ecologically and evolutionarily important traits. Given that many marine species have swimming or drifting larvae but sedentary or sessile adult stages, new insights into the spatial scale of ecological and evolutionary processes in these species are critical to inform management practices (e.g. the design of marine reserves and reserve networks), and to predict the course of biological invasions.

As the tools to measure and estimate population structure and relatedness/kinship are developing rapidly, evaluation of fine-scale population structure in field studies is likely to reveal that opportunities for kin selection are far more widespread in the sea than is generally recognized. Where studies in both terrestrial and marine systems still lag far behind is in estimating the other crucial elements of Hamilton's inequality, namely the costs and benefits of altruistic behaviours, and how these costs and benefits contextually vary [42]. Across the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary timescales, marine organisms, with their unrivalled diversity of mating systems, fertilization, reproductive and developmental modes, offer a novel and compelling arena within which to examine all of these aspects of social evolution, many of which are just beginning to be investigated in terrestrial organisms.

Funding statement

R.K.G is supported by NSF (ANB041673 and OCE 0909078).

References

- 1.Hamilton WD. 1964. Genetical evolution of social behaviour. J. Theor. Biol. 7, 1–52 (doi:10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourke AFG, Franks NR. 1995. Social evolution in ants. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leggett HC, El Mouden C, Wild G, West S. 2012. Promiscuity and the evolution of cooperative breeding. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 1405–1411 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1627) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffy JE. 1996. Eusociality in a coral-reef shrimp. Nature 381, 512–514 (doi:10.1038/381512a0) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keough MJ. 1984. Kin recognition and the spatial distribution of larvae of the bryozoan Bugula neritina (L). Evolution 38, 142–147 (doi:10.2307/2408553) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosberg RK, Quinn JF. 1986. The genetic control and consequences of kin recognition by the larvae of a colonial marine invertebrate. Nature 322, 456–459 (doi:10.1038/322456a0) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buss LW. 1981. Group living, competition, and the evolution of cooperation in a sessile invertebrate. Science 213, 1012–1014 (doi:10.1126/science.213.4511.1012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayre DJ, Grosberg RK. 1996. Effects of social organization on inter-clonal dominance relationships in the sea anemone Anthopleura elegantissima. Anim. Behav. 51, 1233–1245 (doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0128) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez AV, Santelices B. 2008. Coalescence and chimerism in Codium (Chlorophyta) from central Chile. Phycologia 47, 468–476 (doi:10.2216/07-86.1) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosberg RK. 1988. The evolution of allorecognition specificity in clonal invertebrates. Q. Rev. Biol. 63, 377–412 (doi:10.1086/416026) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puill-Stephan E, van Oppen MJH, Pichavant-Rafini K, Willis BL. 2012. High potential for formation and persistence of chimeras following aggregated larval settlement in the broadcast spawning coral, Acropora millepora. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 699–708 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padilla DK, Harvell CD, Marks J, Helmuth B. 1996. Inducible aggression and intraspecific competition for space in a marine bryozoan, Membranipora membranacea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41, 505–512 (doi:10.4319/lo.1996.41.3.0505) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner VLG, Lynch SM, Paterson L, Loen-Cortes JL, Thorpe JP. 2003. Aggression as a function of genetic relatedness in the sea anemone Actinia equina (Anthozoa: Actiniaria). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 247, 85–92 (doi:10.3354/meps247085) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherman PW, Reeve HK, Pfennig DW. 1997. Recognition systems. In Behavioural ecology. An evolutionary approach (eds Krebs JR, Davies NB.), pp. 69–96 Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buss LW. 1990. Competition within and between encrusting clonal invertebrates. TREE 5, 352–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getz WM. 1981. Genetically based recognition systems. J. Theor. Biol. 92, 209–226 (doi:10.1016/0022-5193(81)90288-5) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldgarden M, Yund PO. 1992. Allorecognition in colonial marine invertebrates: does selection favor fusion with kin or fusion with self? Biol. Bull. 182, 155–158 (doi:10.2307/1542190) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart MW, Grosberg RK. 1999. Kin interactions in a colonial hydrozoan (Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus): population structure on a mobile landscape. Evolution 53, 793–805 (doi:10.2307/2640719) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes RN. 1989. A functional biology of clonal animals. London, UK: Chapman & Hall [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguirre JD, Marshall DJ. 2012. Genetic diversity increases population productivity in a sessile marine invertebrate. Ecology 93, 1134–1142 (doi:10.1890/11-1448.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguirre JD, Marshall DJ. 2012. Does genetic diversity reduce sibling competition? Evolution 66, 94–102 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01413.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamel SJ, Hughes AR, Grosberg RK, Stachowicz JJ. 2012. Fine-scale genetic structure and relatedness in the eelgrass Zostera marina. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 447, U127–U164 (doi:10.3354/meps09447) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stachowicz JJ, Kamel SJ, Hughes AR, Grosberg RK. 2013. Genetic relatedness influences plant biomass accumulation in eelgrass (Zostera marina). Am. Nat. 181, 715–724 (doi:10.1086/669969) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.File AL, Murphy GP, Dudley SA. 2012. Fitness consequences of plants growing with siblings: reconciling kin selection, niche partitioning and competitive ability. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 209–218 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1995) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White C, Selkoe KA, Watson J, Siegel DA, Zacherl DC, Toonen RJ. 2010. Ocean currents help explain population genetic structure. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1685–1694 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berumen ML, Almany GR, Planes S, Jones GP, Saenz-Agudelo P, Thorrold SR. 2012. Persistence of self-recruitment and patterns of larval connectivity in a marine protected area network. Ecol. Evol. 2, 444–452 (doi:10.1002/ece3.208) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christie MR, Johnson DW, Stallings CD, Hixon MA. 2010. Self-recruitment and sweepstakes reproduction amid extensive gene flow in a coral-reef fish. Mol. Ecol. 19, 1042–1057 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04524.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barshis DJ, Sotka EE, Kelly RP, Sivasundar A, Menge BA, Barth JA, Palumbi SR. 2011. Coastal upwelling is linked to temporal genetic variability in the acorn barnacle Balanus glandula. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 439, 139–150 (doi:10.3354/meps09339) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernardi G, Beldade R, Holbrook SJ, Schmitt RJ. 2012. Full-sibs in cohorts of newly settled coral reef fishes. PLoS ONE 7, e44953 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044953) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knight-Jones EW. 1953. Laboratory experiments on gregariousness during settling in Balanus balanoides and other barnacles. J. Exp. Biol. 30, 584–599 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hedgecock D, Pudovkin AI. 2011. Sweepstakes reproductive success in highly fecund marine fish and shellfish: a review and commentary. Bull. Mar. Sci. 87, 971–1002 (doi:10.5343/bms.2010.1051) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iacchei M, Ben-Horin T, Selkoe KA, Bird CE, Garcia-Rodriguez F, Toonen RJ. 2013. Combined analyses of kinship and FST suggest potential drivers of chaotic genetic patchiness in high gene-flow populations. Mol. Ecol. 22, 3476–3494 (doi:10.1111/mec.12341) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamel SJ, Marshall DJ, Grosberg RK. 2010. Family conflicts in the sea. TREE 25, 442–449 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2010.05.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elgar MA, Crespi BJ. 1992. Cannibalism. Ecology and Evolution among diverse taxa. Oxford, UK: Oxford Science Publications [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brante A, Fernandez M, Viard F. 2008. Effect of oxygen conditions on intracapsular development in two calyptraeid species with different modes of larval development. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 368, 197–207 (doi:10.3354/meps07605) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CE, Strathmann RR. 1998. Scaling of gelatinous clutches: Effects of siblings’ competition for oxygen on clutch size and parental investment per offspring. Am. Nat. 151, 293–310 (doi:10.1086/286120) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamel SJ, Grosberg RK. 2012. Exclusive male care despite extreme female promiscuity and low paternity in a marine snail. Ecol. Lett. 15, 1167–1173 (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01841.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamel SJ, Oyarzun FX, Grosberg RK. 2010. Reproductive biology, family conflict, and size of offspring in marine invertebrates. Integr. Comp. Biol. 50, 619–629 (doi:10.1093/icb/icq104) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sagebakken G, Ahnesjo I, Braga Goncalves I, Kvarnemo C. 2011. Multiply mated males show higher embryo survival in a paternally caring fish. Behav. Ecol. 22, 625–629 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arr023) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Z, Hamel JF, Mercier A. 2012. Marked shifts in offspring size elicited by frequent fusion among siblings in an internally brooding marine invertebrate. Am. Nat. 180, E151–E160 (doi:10.1086/667862) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercier A, Sun Z, Hamel JF. 2011. Internal brooding favours pre-metamorphic chimerism in a non-colonial cnidarian, the sea anemone Urticina felina. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 3517–3522 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0605) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A. 2007. Evolutionary explanations for cooperation. Curr. Biol. 17, R66–R672 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]