Abstract

Background:

To determine the incidence and demographic features of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) in south Sharqiyah, Sultanate of Oman.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective review of Omani patients diagnosed as IIH in Sur Regional Hospital from January 2001 to December 2011 was carried out. All patients fulfilled the modified Dandy criteria for IIH. Data collected included age and sex of patients, age of onset of the disease, body mass index (BMI), presence of comorbid conditions, and medication use. Findings of ophthalmic examination, neuroimaging, and neurological assessment were recorded. Total number of new outpatients in the study period and the 2010 south Sharqiyah mid-population statistics were also collected.

Results:

Forty patients were diagnosed as IIH during a period of 11 years from January 2001 to December 2011 in Sur Regional Hospital. The female to male ratio was 3:1; of the 40 patients; 30 (75%) females and 10 (25%) males. Thirteen patients (32.5%) were children below 15 years. Of females in the child bearing age (15-44 years), 60% were obese. As per 2010 census, the Omani population in south Sharqiyah region was 166,318. The calculated annual incidence per 100,000 persons of general population was 2.18. Annual incidence in women of all ages per 100,000 persons was 3.25 and in women of child bearing age was 4.14. In children below 15 years, the incidence was 1.9 per 100,000 children; it was 2.96 per 100,000 for female children.

Conclusion:

This study shows that the incidence in south Sharqiyah is comparable to that of other countries. Females and obese patients are at a higher risk of developing IIH. Obesity is not a risk factor in males and children. Nearly 60% of the females in the child bearing age were obese.

Keywords: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, incidence, obesity, papilledema

Introduction

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is the term commonly used for the association of increased intracranial pressure without clinical, laboratory, or radiological evidence of an intracranial space occupying lesion.[1] Formerly known as benign intracranial hypertension or pseudo tumor cerebri, IIH is a diagnosis of exclusion made in the presence of papilledema, normal neuroimaging, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis but with an elevated CSF opening pressure.[2,3]

The incidence of IIH varies throughout the world and ranges from 0.57 to 2/100,000 in the general population.[3,4,5,6,7] It is common in countries with an increased incidence of obesity.[4,5,6,7] Females in the child bearing age are more commonly affected.[7,8] Other risk factors are intake of drugs such as high dose Vitamin A derivatives (e.g., isotretinoin for acne), long-term tetracycline use, steroid intake or withdrawal, and hormonal contraceptives.[9]

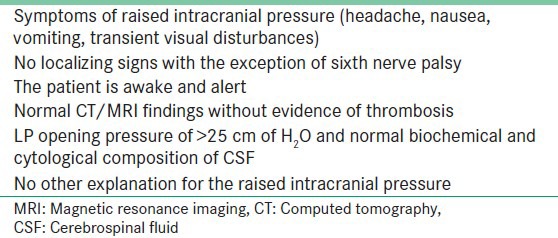

Patients with IIH may present with severe headache, nausea, vomiting, transient visual obscurations, and sometimes diplopia. To establish a diagnosis of IIH, modified Dandy criteria must be fulfilled [Table 1].

Table 1.

Modified dandy criteria[2]

The aim of this study was to determine the population-based incidence and provide the demographic features of IIH in south Sharqiyah region of Oman.

Materials and Methods

The charts of all Omani patients residing in Sur, and diagnosed as IIH based on modified Dandy criteria in Sur regional hospital from January 2001 to December 2011 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with chronic headache and evidence of papilledema who had shown improvement with oral actetazolamide and those who got relief after lumbar puncture (LP) were included. Cases seen in Jalan polyclinic and Sur polyclinic were referred for detailed examination to Sur regional hospital. Children below 6 years and females above 44 years were not included in the study. Those with refractive errors and pseudo neuritis who were relieved of headache after using glasses were excluded. Patients with other systemic diseases such as anemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic renal diseases were not included.

Data collected included age and sex of patients, age of onset of the disease, body mass index (BMI), presence of comorbid conditions, and medication use. Findings of ophthalmic examination, neuroimaging, and neurological assessment were recorded. Total number of new outpatients in the study period and the 2010 south Sharqiyah mid-population statistics were also collected.

All the patients presented with headache and with evidence of papilledema underwent a detailed ophthalmic evaluation. This included Snellen visual acuity, refraction, color vision, and visual field study with the Humphrey Field analyzer (HFA) except in children. Computed tomography (CT) scan brain was done for 35 patients and 5 underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain as there was contraindication for contrast medium. LP was done in all patients and the opening pressure was found to be high (>25 cm of H2O).

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was analyzed for biochemical and cytological composition. Patients were followed up in the eye clinic monthly for first 6 months, bimonthly for next 6 months, and 3-4 monthly thereafter for vision, visual fields, color vision, and fundus examination.

All cases were analyzed for age and sex distribution, age of onset of the disease and presence of obesity. Institutional Research Board approval was obtained prior to conduct of this study.

Results

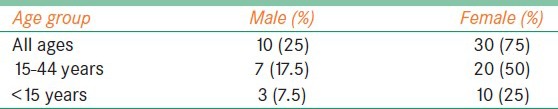

There were 40 diagnosed cases of IIH (30 females, 10 males). The mean age of presentation was 25 years (range 6-44 years). Twenty of the females were in the child bearing age group of 15-44 years and 10 below 15 years. Among the 20 females, 12 were obese. Obesity was not a significant factor in children [Table 2]. However, data regarding BMI was available only for 13 patients (one male and 12 female). Among these, seven patients were diagnosed as obese. BMI for four females was >30 and in two other females, it was >35.

Table 2.

Age and sex distribution of study population

All patients presented with headache, six of them had blurring of vision and four had transient obscuration following coughing or bending. Two children had complaints of giddiness. Visual acuity was normal in 30 patients, 10 of them had refractive errors mainly myopic astigmatism and were corrected. Fields were done in all adult patients. Enlargement of blind spot was seen in 50% of patients. One female patient, who was on hormonal contraceptive, presented with bilateral restriction of abduction. One child had nystagmus and in all other patients ocular movements were full. Ophthalmoscopy in all patients showed papilloedema varying from polar blurring to frank edema. CT brain was normal in 35 patients, 5 patients showed narrow ventricles and MRI in one patient showed empty sella. Thirty patients were relieved of symptoms after giving oral diamox for 3–6 months, but symptoms recurred in eight patients after 1 year. Treatment was restarted in those patients. Visual acuity, color vision, and fields were maintained in all patients. Four patients (two adults and two children) had relief of symptoms after the initial LP and disc edema showed resolution. Six patients, in whom symptoms persisted were referred to neurosurgery and underwent repeated LP (three patients) and lumbo-peritoneal shunt (two patients). One patient refused any type of intervention and was lost to follow up.

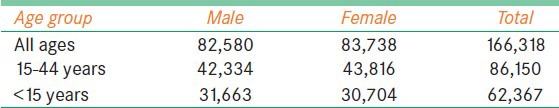

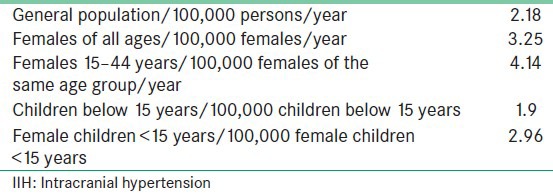

The number of new cases seen in the ophthalmology department of Sur Regional Hospital from January 2001 to December 2011 was 44,804. As per the 2010 census, the Omani population in south Sharqiyah was 166,318. There were 82,580 males and 83,738 females. Females in the 15-44 age groups were 43,816 and children below 15 years were 62,367 [Table 3]. The incidence of IIH in the Omani Population of south Sharaqiah Region based on the current study was calculated and is shown in Table 4. The incidence is more among the females of child bearing age. 60% of these females were obese.

Table 3.

Population distribution of south Sharqiyah as per census of 2010

Table 4.

The calculated incidence of IIH in the Omani population of south Sharqiyah region based on the current study

Discussion

Our study found an annual incidence of 2.18 per 100,000 cases of IIH per year in the general population, which is slightly more than the international statistics (0.57-2/100,000 persons). Studies of American-based populations by Durcan et al., in Iowa and Louisiana, have estimated that the incidence ranges from 0.9 to 1.0 per100,000 in the general population.[4] A study conducted by Department of Neurology, Medical University, Benghazi, Libya showed an annual incidence of 2.2/100,000 persons, which is very close to our study.[5] Radhakrishanan reported an incidence of 1 per 100,000 persons in Rochester, Minnesota.[3] In the Sheffield, UK study it was 1.56/100,000/year.[6] The study conducted by Department Of Neurology, Tel-Aviv University, Israel reported a very low incidence of 0.57-0.94 per 100,000 persons.[7]

The female preponderance and relatively high frequency of obesity found in many previous surveys were also found in our study. Incidence in females of all ages was 3.25 per 100,000 females and 4.14 in the age group of 15-44 years. Annual incidence from Mayo Clinic showed a lower figure, 1.6 cases per 100,000 women of all age groups and 3.3 cases per 100,000 females aged 15-44 years.[3] Study from Libya showed a higher number, 4.3 cases per 100,000 women of all age groups and 12 cases in the 15-44 age group.[5] Study from Israel showed 1.82 per 100,000 women and 4.02 in the child bearing age group.[7] UK study showed an annual incidence of 2.86/100,000 women.[6] The incidence of IIH in countries such as Libya and Saudi Arabia is likely to be higher than in Western countries because of the higher prevalence of obesity among females of reproductive age.[8] We found a female to male ratio of 3:1 in our population, which is low in comparison with other studies. In our study, 60% of females were obese. No similar statistics were found in affected males. Twelve females were reported as obese, six of them by the clinical impression and six according to their BMI. Four females and one male had BMI > 30 and two females had BMI > 35. Women who are more than 10% over their ideal body weight are 13 times more likely to develop IIH and this figure goes up to 19 times in women who are more than 20% over their ideal body weight.[10] For men, the increase is only 5-fold in those over 20% above their ideal body weight. The pathophysiology of IIH in obese people is linked to an increase in intracranial venous pressure and impaired venous return due to obstructive sleep apnea (forced inspiration against a closed glottis). In addition, obstructive sleep apnea leads to retention of carbon dioxide. This hypercapnia can induce cerebral venous dilation and transient elevations in intracranial pressure.[11] In the study from Israel, the F: M was 14:1, the F: M ratio was 1:8 in the Johnson study.[7] In the Durcan et al. study, the F: M ratio was 8:1.[4] The median age at diagnosis in most of the studies was 30 years; it was 25 years in our study.

Another interesting aspect in our study was a higher incidence in children below 15 years. Thirteen children, 3 boys and 10 girls were diagnosed to have IIH. They constituted 32.5% of the total cases. These children were not obese. There is no known genetic cause for IIH. Incidence in our study was 1.9 per 100,000 children < 15 years and 2.96 cases per 100,000 female children below 15 years. This is very close to the incidence in general population and to females of all age groups. Female to male ratio was 3.33:1. As per the literature, there is no difference in incidence between male and female children.[12] A study from Israel in pediatric population showed a female to male ratio of 14:13.[13]

In conclusion, in this retrospective study of all diagnosed cases of IIH that presented to Sur Regional hospital for a period of 11 years, the incidence in the general population was slightly higher than the international statistics, but the incidence in the females was in between that of Western countries and other Middle-East countries like Libya and Saudi Arabia. Female to male ratio was low compared with studies from other countries. The incidence in children was high, almost similar to that in the general population. Any other unidentified risk factor, which can contribute to its occurrence in children, needs further evaluation.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help and cooperation of colleagues in Department of Ophthalmology, Sur Regional Hospital.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Skau M, Brennum J, Gjerris F, Jensen R. What is new about idiopathic intracranial hypertension? An updated review of mechanism and treatment. Cephalalgia. 2006;4:384–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;59:1492–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000029570.69134.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radhakrishnan K, Ahlskog JE, Cross SA, Kurland LT, O’Fallon WM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumour cerbri). Descriptive epidemiology in Rochester, Minn, 1976 to1990. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:78–80. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540010072020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durcan FJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumor cerebri. Population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:875–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520320065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radhakrishnan K, Thacker AK, Bohlaga NH, Maloo JC, Gerryo SE. Epidemiology of Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. A prospective and case-control study. J Neurol Sci. 1993;1:18–28. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90084-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raoof N, Sharrack B, Pepper IM, Hickman SJ. The incidence and prevalence of Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in Sheffield, U.K. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:1266–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kesler A, Gadoth N. Epidemiology of Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in Israel. J Neuroophthalmol. 2001;1:12–4. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200103000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkali NH, Daif A, Dorsanamma M, Almoallem MA. Prognosis of Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in Saudi Arabia. Ann Afr Med. 2011;10:314–5. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.87051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binder DK, Horton JC, Lawton MT. ‘Idiopathic intracranial hypertension’. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:538–51. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000109042.87246.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhungana S, Sharrack B, Woodroofe N. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;2:71–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lettieri CJ. The 5 most common ocular manifestations of obstructive sleep apnea. Medscape Pulmonary medicine. 2013:10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babikian P, Corbett J, Bell W. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in children, the Iowa experience. J Child Neurol. 1994;9:144–9. doi: 10.1177/088307389400900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kesler A, Fattel-Valevski A. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in the paediatric population. J Child Neurol. 2002;10:745–8. doi: 10.1177/08830738020170101401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]