Abstract

Context

Recurring problems with patient safety have led to a growing interest in helping hospitals’ governing bodies provide more effective oversight of the quality and safety of their services. National directives and initiatives emphasize the importance of action by boards, but the empirical basis for informing effective hospital board oversight has yet to receive full and careful review.

Methods

This article presents a narrative review of empirical research to inform the debate about hospital boards’ oversight of quality and patient safety. A systematic and comprehensive search identified 122 papers for detailed review. Much of the empirical work appeared in the last ten years, is from the United States, and employs cross-sectional survey methods.

Findings

Recent empirical studies linking board composition and processes with patient outcomes have found clear differences between high- and low-performing hospitals, highlighting the importance of strong and committed leadership that prioritizes quality and safety and sets clear and measurable goals for improvement. Effective oversight is also associated with well-informed and skilled board members. External factors (such as regulatory regimes and the publication of performance data) might also have a role in influencing boards, but detailed empirical work on these is scant.

Conclusions

Health policy debates recognize the important role of hospital boards in overseeing patient quality and safety, and a growing body of empirical research has sought to elucidate that role. This review finds a number of areas of guidance that have some empirical support, but it also exposes the relatively inchoate nature of the field. Greater theoretical and methodological development is required if we are to secure more evidence-informed governance systems and practices that can contribute to safer care.

Keywords: governing boards, trustees, patient safety, quality improvement

As corporate entities with statutory oversight responsibilities, hospital governing boards are accountable for the overall quality and safety of the care their hospitals provide. They therefore have a fundamental governance role in the oversight of quality and safety, by defining priorities and objectives, crafting strategy, shaping their culture, and designing systems of organizational control. However, recurrent problems with quality and patient safety on both sides of the Atlantic have raised concerns about the boards’ ability to discharge these duties with appropriate effect (Conway 2008; Francis 2013; Jha and Epstein 2010).

In the United States, the Institute of Medicine's landmark report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (IOM 1999) makes clear that health care organizations must attend to quality and patient safety. Since then, however, improvement in the standard of hospital care has been frustratingly slow (Landrigan et al. 2010; Leistikow, Kalkman, and de Bruijn 2011; Wachter 2010), and boards, especially, appear to have paid insufficient attention to quality and safety (Curran and Totten 2010; Jha and Epstein 2010). In the United States, the 2010 Affordable Care Act requires hospital boards to take an active role in strengthening their governance processes to ensure that quality and efficiency are improved. Formal guidance, advice, and supporting tools have been developed to help enhance hospital boards’ effectiveness in this regard (Belmont et al. 2011b) and also in recognition of the organizational and environmental pressures they face. The reorganization of hospital services into various forms of multiunit systems exemplify these current changes to governance activity, oversight, and decision-making responsibilities, which may well require a substantial modification of the boards’ role (Alexander and Lee 2006; Alexander, Weiner and Succi 2000; Alexander et al. 2009; Prybil 1991).

In the English National Health Service (NHS), recent high-profile reports of serious failings in hospital quality have rekindled concerns about the boards’ effectiveness (House of Commons Health Committee 2009). Poor board leadership and governance have long been a theme of investigations into hospital scandals in England, such as the mistreatment of long-stay patients at Ely Hospital (Secretary of State 1969) and, perhaps most notorious, the tragic events at Bristol Royal Infirmary, where poor board leadership was linked to high death rates in pediatric cardiac surgery (Kennedy 2001). More recently, in February 2013, the report of the public inquiry chaired by Robert Francis, QC, into the standard of care at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust estimated that as many as 1,200 people had died unnecessarily in the hospital between 2005 and 2008, resulting from a tolerance for poor standards in the organization that had been fostered by poor leadership and the management board's focus on achieving financial targets rather than safeguarding patients’ welfare (Francis 2013).

Despite significant concerns about quality and safety in health care, which boards are clearly central to addressing, the evidence base to support action is unclear. Only relatively recently has research focused on governing boards and governance practices (Prybil, Bardach, and Fardo 2013). Although both standards and guidance on board oversight (Belmont et al. 2011a; Conway 2008; Joint Commission 2011) and summaries of evidence of the effectiveness of board oversight of quality and safety (e.g., Clough and Nash 2007; Oetgen 2009; Ramsay et al. 2013) have been produced, the research base has not yet been fully exploited. The purpose of this article, therefore, is to review and synthesize the rapidly expanding evidence base in relation to board oversight of quality and patient safety, with the intention of informing future research, practice, and policy development.

Methods

Systematic reviews are an established means of summarizing available research. A number of approaches are available (see table 1), and selection depends on the review's aims and the nature of the evidence to be explored (Popay et al. 2006; Rodgers et al. 2009). Given the diffuse, emergent, and contested nature of the literature on governance of quality and patient safety and our primary objective of describing, interpreting, and synthesizing key findings and important contours of debate, we undertook a narrative systematic review. We aimed to produce a synthesis that would embrace the complexities and ambiguities associated with the topic and identify different narratives of board oversight related to quality and safety, in an inclusive and holistic manner and with the intention of supporting the development of policy, practice, and future empirical work.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Alternative Approaches to Systematic Review

| Systematic Review Approach | Unit of Analysis | Focus of Observation | End Product | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | Program | Effect sizes | Relative power of like programs | Whole program application |

| Narrative review | Program | Holistic comparison | Recipes for successful programs | Whole or majority replication |

| Realist synthesis | Mechanisms | Mixed fortunes of programs in different settings | Theory to determine best application | Mindful employment of appropriate mechanisms |

Source: Adapted from Popay et al. 2006, 89.

We built on previous applications of the narrative approach to patient safety (Waring et al. 2010) and health care more generally (Greenhalgh et al. 2009; McCreaddie and Wiggins 2008; Powell, Rushmer, and Davies 2009). Iterative searches enabled us to refine the initially broad parameters of our exploratory searches and to identify story lines in the literature and map their development over time (Greenhalgh et al. 2005).

Finding Papers for the Review

To ensure rigor, we followed the accepted practice in identifying the review's focus, specifying the review question, searching for and mapping the available evidence, and identifying studies for inclusion (Greenhalgh et al. 2005). In selecting papers, we concentrated on those that considered board oversight in the context of quality and safety, and the research team and expert panel suggested seminal works and advised on search terms. The team drew up a list of key terms and searched the published literature from 1991 to the present across a number of databases, excluding articles not written in English.

The team then reviewed titles and abstracts for relevance, using broad inclusion criteria to identify studies of hospital board directors’ or boards of trustees’ oversight of quality and patient safety. In an earlier review, Clough and Nash (2007) identified 53 relevant articles that had been published after 1990. Our initial search uncovered 187 articles, and after reviewing their titles and abstracts, we settled on a subset of 66 papers for detailed study, which we added to those of the earlier review, removing duplicates. Disagreements on whether to select a reference for full review were resolved by discussion within the team. Finally, we used snowballing techniques to augment papers for review—manually, by searching references of included papers, and electronically, by using citation-tracking software to identify papers that cited already-included papers. These searches were adapted iteratively to ensure maximum capture of empirical work, and at the end of the process, we deemed 122 publications to be relevant (full list available from the authors).

Making Sense of the Published Literature

We followed guidance on narrative synthesis from Popay and colleagues (2006) in our data extraction and appraisal of study quality. Our main goal was to understand the effectiveness of oversight in terms of board composition and interventions with boards, such as setting standards and benchmarks. In particular, we were keen to explore any evidence for improved performance and patient outcomes—such as reductions in mortality and morbidity—from board interventions, as well as identifying those factors affecting the implementation of those board interventions.

The synthesis phase of our review explored key aspects of board oversight of quality and patient safety. Thematic mapping led to emergent coding and categorization, consistent with our review themes, which were themselves developed iteratively and in discussion with our advisory panel, to enable us to systematically identify the recurrent and most important themes and concepts across multiple studies (Popay et al. 2006). We identified four common story lines: leading for safer care, measuring safe care, implementing internal board oversight, and relying on external regulation and accountability. After a brief historical account of the growth of the field, we examine each story line and present a narrative synthesis.

Our review and synthesis built on evidence generated from systematic searches and the research team's contributions, but our searches may have missed some studies. For example, although we did not include the book by Jennings and colleagues (2004), we subsequently did incorporate into our review the important research evidence that it contains (Gray and Weiss 2004). We also attempted to mitigate the subjective selection and arrangement of recurrent themes (Rodgers et al. 2009) by weighting study appraisal in favor of published empirical studies that had transparent, explicit methods and research design. These major empirical studies (summarized in table 2) were the central focus of the review and were supplemented by additional forms of evidence, commonly referred to as “gray literature,” which enabled us to consider standards, practices, and procedures related to the effective board oversight of patient safety. Decisions about including or excluding such studies were based on the extent to which studies provided evidence of boards’ effectiveness in relation to quality and patient safety.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Major Empirical Studies Exploring Board Oversight of Safe Care

| Participants | Context (aims) | Board Assessment (methods) | Summary of Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al. 2010 | ||||

| Canada and United States | 15 governance experts, average of 10 board members across 4 case studies, survey of Quebec and Ontario health economies | To identify governance practices and improve governance related to patient safety | Semi-structured interviews, documentary analysis, and survey | Effective governance is in its early stages. Better information, expertise, plans, skills, and relationships still are required. |

| Gray and Weiss 2004 | ||||

| United States | 98 CEOs and trustees from 16 nonprofit hospitals in New York City area | To learn about how trustees define their responsibilities; how they relate to hospital activities; and how they make decisions | Structured open-ended interviews with trustees and CEOs | Governance by boards was a strength and weakness for nonprofit hospitals. Fundamental ambiguities in the ethical significance of the trustee role were identified. |

| Goeschel et al. 2011 | ||||

| United States | 35 boards from cross section of hospitals across Tennessee and Michigan | To identify effective measures for monitoring quality | Survey and voluntary site request for safety scorecards | Measures varied widely with uncertain validity. More valid outcome measures are required. |

| Jha and Epstein 2010 | ||||

| United States | 722 chairpersons from nonprofit acute care hospitals | To determine board engagement and activities in relation to quality of care | Survey and composite measures of hospital performance | Quality of care is often not a top priority, with differences in quality-related activities between high- and low-performing institutions. |

| Jha and Epstein 2012 | ||||

| United States | 722 chairpersons from “black-serving” and “non-black-serving” nonprofit hospitals | To compare how boards at black-serving and non-black-serving hospitals engage in quality of care issues | Survey and composite measures of hospital performance | Board chairs of black-serving hospitals report less expertise and priorities for quality issues than do chairs of non-black-serving hospitals. |

| Jha and Epstein 2013 | ||||

| United Kingdom | 132 chairpersons from a cross section of English hospitals | To compare governance practices among English and U.S. hospital boards | Survey and composite measures of hospital performance | English board chairs report greater expertise and emphasis on quality of care issues than do U.S. board chairs. However hospital performance against quality metrics is not as substantial as in U.S. |

| Jiang et al. 2008 | ||||

| United States | 562 hospital presidents/CEOs across 50 states selected from the 2006 Governance Institute (TGI) survey | To examine the prevalence and impact of particular board activities | Survey and composite measures of hospital performance | Governing boards are engaged in quality oversight, particularly through internal data and national benchmarks. |

| Jiang et al. 2009 | ||||

| United States | Based on Jiang et al.'s (2008) data set | To examine differences in hospital quality performance associated with particular practices | Based on Jiang et al. 2008 | Better performance is associated with having a board quality committee, strategic goals, a quality agenda, safety dashboards/benchmarks, and the involvement of physician leaders. |

| Jiang, Lockee, and Fraser 2011 | ||||

| United States | 445 hospitals selected from the 2007 Governance Institute (TGI) survey | To explore the practices of governing boards in quality oversight through the lens of agency theory | Survey and composite measures of care and mortality | Regularly reviewing quality performance is the most common practice. |

| Joshi and Hines 2006 | ||||

| United States | 47 CEOs and board chairpersons from cross section of 30 hospitals across 14 states | To determine whether hospital leaders understand safety and quality issues and activities | Interview survey and composite measures of clinical quality | Overall level of knowledge is low, with significant differences between perceptions and some association between board engagement and hospital performance. |

| Kroch et al. 2006 | ||||

| United States | Convenience sample of 139 hospitals across 9 states | To analyze hospital board dashboards and their relationship to leadership engagement | Online dashboard implementation survey and performance data analysis using composite measures | Variation and commonalities were found in the way dashboards are created and used. Improved quality was linked to shorter, more focused dashboards. |

| Machell et al. 2010 | ||||

| United Kingdom | Nurse executives and boards in six English NHS hospital trusts | To examine the board's focus on clinical quality and the role of nurse executives in supporting this | Observations | Clinical quality occupied a fragile position. Nurse executives are well placed to help. |

| Mastal, Joshi, and Schulke 2007 | ||||

| United States | 73 hospital CEOs, chief nursing officers, and chairs from 63 hospitals | To analyze the board's engagement in quality and safety and the role of nursing in this | Telephone interviews and focus group | Significant differences in perceptions of CNOs, chairs, and CEOs. Boards had only limited comprehension of salient nursing quality issues. |

| Prybil et al. 2010 | ||||

| United States | CEOs from 123 nonprofit community health systems | To examine oversight of patient quality at nonprofit community health systems and compare this with benchmarks of good governance | Survey and benchmark analysis | Activities associated with effective governance include standing committees and safety targets/reports. Gaps continued to be found between present reality and current benchmarks. |

| Prybil, Bardach, and Fardo 2013 | ||||

| United States | Senior trustees and CEOs from 14 private nonprofit health systems | To examine board oversight of quality in private nonprofit health systems and compare this with benchmarks of good governance | Documents, interviews, and benchmark analysis | Effective governance in majority of boards was identified with presence of standing committees, systemwide quality measures, and action plans directed at improving quality. |

| Ramsay, Magnusson, and Fulop 2010 | ||||

| United Kingdom | Case study of 21 personnel, including board members from a hospital trust in England | To describe the external and internal governance systems for health care–associated infections and medication errors in an NHS trust | Documentary analysis and interviews | Nationally, health care–associated infections had higher priority than medication errors. Governance of medication errors took place at divisional or ward level. |

| Vaughn et al. 2006 | ||||

| United States | CEOs and senior executives from a cross section sample of 413 hospitals in 8 states | To identify characteristics of hospital leadership engagement in quality improvement | Survey and composite measures of clinical quality | Better quality was associated with boards spending more than 25% of time on quality issues, receiving formal measurement reports, and communicating a quality strategy to medical staff. |

Findings

A Growing Field of Inquiry

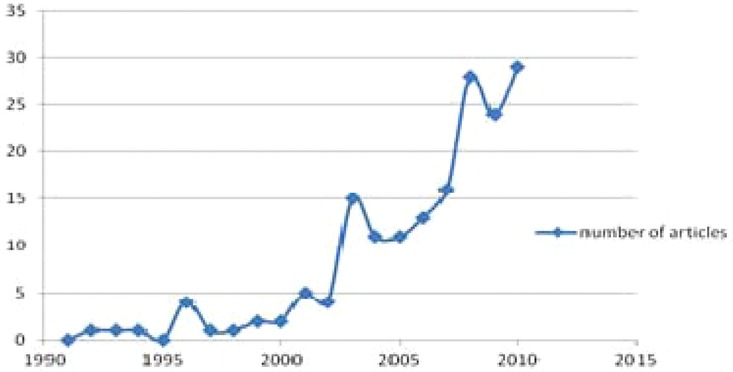

The Institute of Medicine reports, To Err Is Human and Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM 1999, 2001) in the United States, and the chief medical officer's report into learning from adverse events in the United Kingdom, An Organisation with a Memory (Department of Health 2000), were hugely influential in calling for changes to health care systems and organizations that would improve quality and safety. It is therefore not surprising that our results show large and rapid growth since 2000 in the number of published articles regarding hospital board oversight of quality and patient safety (figure 1), a trend that reinforces the increased policy salience of board oversight of safety.

FIGURE 1.

Results of the systematic search of board oversight and patient safety.

The study of board oversight in relation to quality and patient safety can be situated within the broader literature that addresses the role of leadership in improving quality in U.S. hospitals (see Jiang et al. 2008; Kroch et al. 2006; Meyer et al. 2004; Paine et al. 2004; Sandrick 2005). With hospitals’ variable successes in implementing quality improvement programs and initiatives (Jha and Epstein 2010; Jha et al. 2005), the publication in 2004 of empirical studies of U.S. hospitals also reveals variation in the adoption of board practices thought to be associated with higher performance and better patient outcomes (Joshi and Hines 2006; Kroch et al. 2006). These cross-sectional surveys of predominantly nonprofit hospitals indicate the importance of examining the leadership actions believed to influence the effectiveness of quality improvement in hospitals (Vaughn et al. 2006).

In 2008, larger-scale studies began to cover wider geographical areas. Building on their cross-sectional survey of the prevalence and impact of board activities in U.S. hospitals (Jiang et al. 2008), Jiang and colleagues (2009) widened their evaluation of board oversight to include its impact on such clinical outcome measures as mortality, morbidity, and complications, as well as differences in the processes of care. Jha and Epstein (2010) carried out the first national survey of board chairs in the United States to analyze boards’ engagement with clinical quality and to identify differences between boards’ activities in high- and low-performing organizations.

In 2010, studies began to differentiate among and explore board activities related to patient safety in specific socioeconomic, organizational, and geographical contexts. Jha and Epstein (2012) pursued an explicitly socioeconomic focus to compare boards of directors’ priorities and practices in serving the interests of minority-group patients. Prybil and colleagues (2010) examined specific board structures, practices, and cultures related to good governance in U.S. nonprofit community health systems. Baker and colleagues (2010) carried out the first significant study of board governance and quality and safety in Canadian health care organizations, and studies from Britain analyzed the formal governance arrangements for health care–associated infections and medication errors (Ramsay, Magnusson, and Fulop 2010). More recently, Jha and Epstein (2013) conducted the first national survey of English hospital board activities, providing an international comparison with their survey of nonprofit acute care hospital boards in the United States.

The theoretical and conceptual dimensions of board oversight also have received more explicit attention. Jiang, Lockee, and Fraser (2011) employed the agency theory perspective as a lens through which to explore the role and practices of hospital governing boards, while Ford-Eickoff, Plowman, and McDaniel (2011) explored how concepts like complexity absorption and requisite variety can support hospital board governance and oversight, hypothesizing that boards whose members have a greater variety and breadth of expertise can better respond to complex environments and have greater potential for sense-making and learning.

Emerging Story Lines

Our review of board oversight of patient safety found a variety of empirical evidence and expert advice suggesting that specific board activities are associated with improvement in the quality and safety of hospital care. The results also suggest, however, that the adoption of such activities remains variable and that our understanding of boards’ impact on patient safety currently is limited. We present the findings thematically, as four story lines derived from the narrative review: leading for safer care, measuring safe care, implementing internal board oversight, and relying on external regulation and accountability.

Leading for Safer Care

Board oversight of patient safety tends to reflect a key message from the quality improvement literature as a whole, that is, that strong and committed leadership from the CEO and the board is vital to the success of quality improvement and safety programs (e.g., Conway 2008; Gautam 2005; Healthcare Commission 2009b; Sandrick 2005; Schyve 2003). A review by Clarke, Lerner, and Marella (2007) suggests that leadership on patient safety should learn from the characteristics and behaviors of high-reliability organizations such as those found in the nuclear and aviation industries. In health care, leadership is associated with perceiving lapses in patient safety to be a problem with the system rather than with individual employees and—with words and actions that promote a culture that encourages the identification of mistakes—emphasizes systemic improvements that reduce variability and make safety a given.

Empirical evidence from cross-sectional surveys in the United States suggests that boards demonstrating such leadership have a positive impact on their organizations’ safety performance. Boards that place a high priority on quality and safety are associated with higher performance (Jiang et al. 2009), as are boards that set strategic goals for quality improvement and demand reports on the progress of action in response to adverse events (Jiang et al. 2008; Prybil, Bardach, and Fardo 2013). A U.S. national survey of 722 chairpersons by Jha and Epstein in 2007 and 2008 found that respondents from high-performing nonprofit hospitals were more likely than respondents from low-performing nonprofit hospitals to establish and publicly disseminate goals and to perceive themselves as influential throughout the organization (Jha and Epstein 2010).

Although such practices have been found to be associated with effective leadership on patient safety, empirical evidence shows significant variation in their implementation. Drawing on the 2006 the Governance Institute (TGI) survey of 562 chairpersons and CEOs from hospitals across the United States, Jiang and colleagues (2008) found that fewer than half the CEOs regarded their organizations’ governing boards as very effective in overseeing quality. Similarly, in case studies of Canadian and U.S. health care organizations, Baker and colleagues (2010) found that although most boards had established strategic goals for quality improvement, many did not have specific objectives with clearly defined targets, indicating that words were not necessarily backed up by actions. Observation research by Machell and colleagues (2010) on how nurse executives and boards work in acute care hospitals and mental health trusts across England found that many chief nursing officers perceived board members to be only moderately engaged in quality improvement initiatives. This was attributed to the members’ lack of knowledge about quality and patient safety issues, limited time for participating in quality initiatives, and dearth of quality champions at the board level. Such a view is echoed in the qualitative research of nonprofit hospitals in the United States. Gray and Weiss's interviews with CEOs and trustees (2004) in 1998 and 1999 found that the two most important issues for local nonprofit hospital boards in the New York City area were mergers/acquisitions and financial management, with hospital quality and safety receiving far less attention. These findings are consistent with U.S. national survey data from Jha and Epstein (2010) showing that approximately half the nonprofit hospital boards did not rate quality of care as a top priority for board oversight or CEO performance evaluation. Most boards were focused primarily on financial issues and assumed that their quality of care was adequate.

Measuring Safe Care

Board oversight of quality and patient safety rests on the directors’ ability to obtain, process, and interpret information; assess current performance; and set strategic direction using a range of metrics tailored to local circumstances. Expert advice helps boards understand quality and safety performance through the use of checklists and dashboards (Bader 1993; Goeschel, Holzmueller, and Pronovost 2010; Lathrop 1997; Meyers 2004; Pugh and Reinertsen 2007; Slessor, Crandall, and Nielsen 2008). Reinertsen (2007) summarized the steps that trustees can take to manage quality in their organizations by concentrating on a few internal quality measures, or “dots,” and argued that such an approach can generate significant improvements, particularly in building organizational buy-in, maintaining constancy of purpose, and nurturing collaborative effort.

Empirical evidence from U.S. hospital surveys indicates that boards that review and track their organization's performance through the collection and analysis of internally generated data (quality dashboards or scorecards) and national benchmarks are likely to have better outcomes in regard to quality (Jiang et al. 2008, 2009; Jiang, Lockee, and Fraser 2011). This finding is supported by U.S. research by Kroch and colleagues (2006), whose analysis of hospital board dashboard composition found that higher-performing organizations were more likely than their lower-performing counterparts to have dashboards that were shorter and more frequently reviewed and focused on areas critical to quality. In England, single case-study research conducted in 2008 by Ramsay, Magnusson, and Fulop (2010) found that a hospital's scorecard data offered a view of the organization as a whole and facilitated division- and ward-specific analysis and feedback on the governance of health care–associated infections. Empirical studies and expert advice also emphasize, along with the use of formal performance metrics and quantitative data sets, the role of soft intelligence in capturing the qualitative experience of patients and staff, which often defies simple coding and quantification (Baker et al. 2010; Frankel et al. 2003). In the United States, Joshi and Hines's interviews with board chairs and CEOs (2006) identified the measurement of patient centeredness as a key issue for board oversight of quality of care. Joshi and Hines also recommended tapping into informal and soft intelligence channels as a way to safeguard care by including executive walkarounds, having patients tell their stories at board meetings, and allowing board members to shadow clinicians, enabling them to better understand frontline challenges in delivering safe care.

Patient safety metrics clearly are important to any strategy designed to improve care, and the empirical evidence shows a need for increasing board members’ proficiency in the use and interpretation of metrics and for improving the credibility, validity, and reliability of data. Baker and colleagues (2010) found that many Canadian health care organizations had struggled to develop useful measurements for board oversight of quality and patient safety. Their survey of board chairs from hospital as well as regional and community organizations reported that even though boards received and discussed a range of quantitative indicators, only half rated the information as good or excellent in enabling them to accurately assess their organization's performance. In England, research found that the information accessible to hospital boards generally fell short of the then NHS regulator's recommended range of quantitative and qualitative material (Healthcare Commission 2009a) and that more needed to be done to relay information about safety performance to frontline staff (Healthcare Commission 2009b). Jha and Epstein's recent survey of 132 chairpersons in England (2013) also reported a variable use of quality metrics by English hospital boards and found that boards of hospitals with foundation status were more likely than nonprofit boards in the United States to use quality dashboards, request quality reports, and review specific quality data as part of their oversight activities. Variation in the use of metrics by U.S. boards is illustrated by the survey and scorecard analysis by Goeschel and colleagues (2011), which shows significant differences in the use of scorecards across the participating hospitals in Michigan and Tennessee. In contrast, interview and documentary research by Prybil, Bardach, and Fardo (2013) found a high degree of consistency in measurement, with eleven of fourteen large nonprofit health systems in the United States formally adopting systemwide quality measures and standards.

Expert advice has addressed the need for board members to have greater awareness and understanding of quality and safety, recommending that quality expertise be included in board members’ competency profiles and suggesting that boards receive training and continuing education in quality and safety (Healthcare Commission 2009a). Evans (2009) recommended that exams for board members on the use and implementation of quality measures could improve hospitals’ quality and accountability of care.

Empirical studies have assessed the quality literacy of hospital boards by considering members’ participation in formal training programs and the time they set aside to develop knowledge and capability in regard to improving patient safety. Such work has revealed the limited time and resources that many boards devote to such activities. U.S. and Canadian research found a “remarkably low” degree of knowledge among hospital boards about published quality reports and best-practice guidance in relation to safe care (Joshi and Hines 2006), with many board members having little expertise in using and implementing such information (Baker et al. 2010). Formal training for boards on clinical quality also appears to be underdeveloped (Jha and Epstein 2010). Reflecting on the findings of the 2006 Governance Institute survey in the United States, Jiang and colleagues (2009) suggested that the lack of formal training poses specific difficulties for board members from sectors outside health care, as they are less likely to have the technical skills that would enable them to address clinical quality issues. More recently, comparative research by Jha and Epstein (2013) found that chairpersons in NHS hospitals judged their own expertise regarding quality as being greater than their U.S. counterparts did. Moreover, the surveys suggest that board chairs’ assessments of their hospitals’ quality performance (in both England and the United States) are overrated when compared with the external assessments by the Hospital Quality Alliance (in the United States) and the Care Quality Commission (in England).

Implementing Internal Board Oversight

The role of hospital board members in overseeing quality of care is to monitor the strategic plans that senior management develop or to act as advisers and work at the periphery of the decision-making process (Ford-Eikoff, Plowman, and McDaniel 2011; Marren, Feazell, and Paddock 2003). Baker and colleagues (2010) noted that health boards historically tended to delegate the oversight function to medical staff and did not consider quality and safety issues to be their top priority, which might reflect the board members’ recognition of clinical leaders’ expertise and the traditional separation between the responsibilities of administrative and medical staff.

The increasing interest in board oversight of patient safety has also focused on formal organizational structures and processes for safeguarding care, as well as the informal relationships and dynamics between boards and professional groups. One aspect of this is boards’ agendas and the extent to which patient safety is discussed at board meetings. Findings from U.S. hospitals suggest that having quality and safety as a standing item on the board agenda provides a critical lever for engagement in quality and safety issues (Jha and Epstein 2010; Joshi and Hines 2006). Jiang and colleagues (2008) found that even though most board meetings had agenda items on quality, only 41 percent of boards indicated that they spent more than 20 percent of meeting time on quality. Hospitals whose boards spent 20 percent or more of meeting time on quality had better process-of-care rates than hospitals whose boards spent less time on quality (Jiang et al. 2009). This research supports earlier findings on variability among hospitals in relation to the amount of time that boards devoted to quality and safety. In England, qualitative research from the Healthcare Commission (2009a) found that safety was rarely the first item on the board agenda. This is supported by observational research of English hospital boards by Machell and colleagues (2010), whose main conclusion was that considerations of clinical quality were accorded a low priority in boardrooms, compared with financial matters, organizational restructuring, and the need to meet central government performance targets.

The formal structure of boards has also been found to be related to the effective oversight of patient safety (Bader 2006). U.S. national survey data show that boards with a separate quality committee are more likely to be high performing than are those without such a committee. High-performing organizations are more likely to use quality dashboards or scorecards, issue written policy throughout the organization, and establish strategic goals for quality improvement (Jha and Epstein 2013; Jiang et al. 2008, 2009). But qualitative research into a hospital trust in England by Ramsay, Magnusson, and Fulop (2010) found differing opinions about the effectiveness of subcommittees. Despite concern that the duplication of messages might lead to mistakes in reporting, it also was seen as necessary to sustain staff engagement in safety-related issues.

In addition, effective board oversight of safety requires attention to the dynamics and tensions within and among boards, medical staff, and senior leaders (Weiner, Shortell, and Alexander 1997). In particular, expert advice advocates having a physician leader on a board quality committee in order to enhance performance by facilitating communication and building trust and confidence (Marren, Feazell and Paddock 2003; Reinertsen 2007; Weiner, Shortell, and Alexander 1997).

The empirical analysis of the 2007 Governance Institute survey by Jiang and colleagues (2009) found that hospitals in which representatives with clinical expertise served on the board's quality committee performed significantly better on process and outcomes of care than did hospitals that had no such expertise on their boards. Collaborative retreats with multidisciplinary staff groups (Heenan, Khan, and Binkley 2010) and internal collaboratives, built around safety initiatives, also were found to enhance safeguarding processes (Paine et al. 2004).

Although such intergroup dynamics are associated with benefits, expert advice and empirical research highlight the need for board development in this area. Nursing leadership, for example, remains conspicuously absent from many board deliberations and decision making (Machell et al. 2010; MacLeod 2010; Mastal, Joshi, and Schulke 2007; Meyers 2008; Prybil 2007, 2009, 2013). Gray and Weiss (2004) noted that further discussion was required regarding the ethical conflicts and ambiguities that can arise when board members combine professional and clinical interests with corporate roles and duties. Boards’ relationships with the wider patient community also should be considered. A survey of U.S. nonprofit hospitals by Jha and Epstein (2012) conducted in 2008 revealed that board chairs in hospitals serving predominantly black populations reported less expertise and prioritization of quality issues than did chairs of boards in non-black-serving hospitals.

Relying on External Regulation and Accountability

Our primary focus has been on internal processes for board oversight of patient safety, but we also considered research on the external accountability of boards. Case-study research by Baker and colleagues (2010) found that Canadian organizations grappled with the challenge of reconciling the information needed for external accountability with that required to inform local improvements. One dilemma was whether to make performance data publicly available. Some hospitals had made available information on the incidence of clostridium difficile, meticillin-resistant staphylococcus aureusis (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) infections, whereas other hospitals were approaching the issue more cautiously.

In the English NHS, a case study of a hospital by Ramsay, Magnusson, and Fulop (2010) considered the board's accountability in relation to national targets and regulatory bodies for health care–associated infections and medication errors. Although the researchers could not categorically conclude that stronger external governance resulted in more effective local governance, they found that at the time of data collection in 2008, rates of health care–associated infections such as MRSA and clostridium difficile were amenable to metaregulation, for example, through target setting. Medication-error data based on incident reports were identified as being more difficult to govern, because such events tended to be more open to interpretation and to suffer from substantial underreporting.

Qualitative research by the Healthcare Commission (2009a) in England found that despite the onus on commissioners or purchasers of services to drive up quality and safety through contracting and payment systems, there were local variations in the commissioners’ robust information systems in place for holding hospitals to account for the quality of care that they provided. Commissioning practice in holding provider organizations to account varied across health economies from ad hoc requests to providers for reports of serious untoward incidents to the systematic benchmarking of providers against indicators of quality and safety. The research found that the most effective accountability arrangements between commissioners and providers were those that were supported by “relational contracting” and that built on strong personal relationships and collaborative, rather than competitive, partnerships among organizations.

Synthesis

Studies of board governance and patient safety have identified a wide range of governance practices that are associated with higher performance. Some pertain to routine feedback and monitoring in the corporate board environment, such as spending time on quality issues, using quality performance reports, regularly reviewing dashboard indicators to monitor quality, and setting quality goals at the theoretical ideal level rather than average levels or national benchmarks. Others are more strategic in focus, such as involving medical staff in the quality strategy, having a quality subcommittee, and developing new clinical programs and services to meet quality-related criteria. Finally, approaches pertaining to wider systems of governance are important. Examples are the exploration of different ways of producing public reports to enhance transparency and accountability to the community, and the equal involvement of board (corporate) and medical (professional/collegiate) staff in setting the agenda (Jha and Epstein 2010; Jiang et al. 2009; Jiang, Lockee, and Fraser 2011; Vaughn et al. 2006).

Taken together, the findings suggest that empirical studies of patient safety governance are informed by the broad assumption that failures in safety (adverse events) are not brought about solely by individual human error but are conditioned, precipitated, and exacerbated by wider systemic and latent factors in the work environment and organizational context (Waring et al. 2010) and therefore are amenable to control and prevention. This assumption functions as a latent program theory in the field of inquiry, and its influence is clearly seen in the nature of the dependent and independent variables selected in the more recent large-scale quantitative studies considered earlier. To summarize, empirical studies of board oversight of patient safety are clearly situated within a quality and safety paradigm (Vincent 2011).

Methodological and Theoretical Development

Despite such apparent coherence in a relatively new and emergent empirical literature, the field remains methodologically and theoretically underdeveloped. The empirical study of board governance and patient safety consists largely of cross-sectional surveys, predominantly undertaken in U.S. acute health care settings (Jha and Epstein 2010; Jiang et al. 2008). The limitations of this study design are acknowledged and include poor generalizability and an inability to substantiate causal relationships among study variables, as opposed to statistical correlations. Although cross-sectional empirical studies have increasingly specified board processes and reporting arrangements in addition to expected outcomes of good patient safety governance, such as low readmission rates and avoidance of adverse events (Jiang et al. 2008, 2009), hypothesized relationships between dependent and independent variables generally remain badly defined. The implicit assumption that aspects of board oversight lead to high-performing organizations (Joshi and Hines 2006) is plausible, but this relationship is likely to be multidirectional and could be confounded by a variety of factors that are currently not well described in the literature or elaborated in multivariate empirical models.

While empirical studies document the structural characteristics of hospitals in terms of size, ownership, teaching status, urban/rural location, and region within their respective samples, the cross-sectional design has often left implicit or been unable to attribute differences in processes and outcomes of patient care quality and safety of different types of hospitals (e.g., for-profit/nonprofit/community/acute care) and hospital boards (e.g., local/multiunit systems). The analysis of these causal relationships is likely to be important when we consider the current environmental and organizational pressures facing hospitals, particularly those in the United States, given the growing consolidation of hospitals into multiunit systems, as noted earlier.

Theory could play a much more explicit role in the development of hypothesized relationships between independent and dependent variables for empirical testing in this field of inquiry. In addition, a closer relationship between theory and empirical work would strengthen the credibility of advice on how best to govern for patient safety. This is an important consideration, given that the corporate governance literature makes conflicting normative claims about how board members should behave, some of which originate in the assumptions of the theoretical model rather than in the empirical verification of the behavior's ability to achieve a specified outcome. In short, although plenty of advice is available to boards on what they should do, the different expectations of the boards’ purpose lead to conflicting advice. Although Chambers and Cornforth (2010) summarized well the rival theoretical traditions that inform competing schools of corporate governance, it might be helpful to consider briefly the rival theoretical framings of agency and stewardship perspectives on corporate governance, to illustrate their potential for explicit hypothesis generation to underpin empirical inquiry, and to provide an example of how the implicit use of theory may lead to conflicting advice on what boards ought to do.

Agency theories of corporate governance require the board to develop processes to ensure the effective scrutiny of executives, on the assumption that the interests of citizens and officials are not aligned and officials will act to secure their own interests. In contrast, stewardship models assume a greater alignment of interests between executives and citizens and emphasize the importance of board processes in improving performance (Chambers and Cornforth 2010). From an agency perspective, one might reasonably hypothesize that boards that hold executives to account through elaborate systems of audit (checking) will achieve better patient safety outcomes. Alternatively, from a stewardship perspective, one might hypothesize that such systems are likely to reduce the creativity that committed executives require if they are to achieve superior performance (trusting) (Davies and Mannion 2000). Both agency and stewardship framings are found in the patient safety literature, agency in the study by Jiang, Lockee, and Fraser (2011) and stewardship by Prybil and colleagues (2010), who suggested that boards appear to be embracing the stewardship of quality and safety as a fundamental duty. However, in neither case are these models explicitly used to generate testable hypotheses that underpin the empirical work.

While we strongly argue for a more explicit use of the corporate governance literature to guide empirical work, we also encourage greater attention to the potential limits of the corporate governance literature in relation to patient safety. Specifically, we draw attention to the implications of cultural theory (Hood 1999) for governance for patient safety. Hood's model identifies markets and professional clans as bases of authority (modes of governance) that could compete with the corporate board, the implication being that the operation of insurance markets and/or professional bodies may limit a board's ability to govern. Contextual differences are important to the institutional arrangements that characterize health care systems. Comparative evidence of such differences is emerging, most notably Jha and Epstein's (2010) recent observation of substantial differences between boards of directors in England and the United States, which were accounted for by the different roles and resources allocated to board members as well as the different health care systems in each country.

Thus, board oversight as a mechanism for change is likely to lead to different outcomes according to the context. We need to reflect on the extent to which the current field of corporate governance is appropriately conceptualized and applicable to the complex quasi markets, multiunit systems, and professional bureaucracies that tend to characterize health care. In short, greater attention to the theoretical and conceptual basis of board oversight would help the development of the empirical field and would help prevent, for example, advocating simple prescriptions for strong leadership without first defining such leadership, how it is to be obtained, and the causal mechanisms that lead to its desired effects.

Given these methodological and theoretical limitations, it is clear that the quantitative study of board oversight for patient safety requires further work in developing new measures and relationships, underpinned by crisper theorizing. It is especially important to test assumed causal relationships between practices leading to good governance and desired outcomes leading to safer care. Moreover, evaluation programs will need to assess the extent to which interventions are implemented as intended, as well as to search for unintended consequences. In addition, further study of the microprocesses associated with board oversight is required (Dixon-Woods et al. 2012). While qualitative and case-study research is beginning to emerge in this area (Baker et al. 2010; Ramsay, Magnusson, and Fulop 2010), further study of the practices undertaken in the boardroom would provide much-needed insight into exactly how patient safety governance is exercised and experienced.

Concluding Remarks

Despite growing pressures for boards to improve and emerging evidence that more effective board oversight is associated with higher quality of care, efforts to create effective governance for quality and patient safety are only in their early stages. Many boards have focused largely on financial performance and access issues and are still developing the broader skills needed to assume a more corporate role while assembling the necessary expertise in quality and patient safety.

In view of the increasing expectations and pressure to deliver better care more safely, it is more urgent than ever that hospital governing boards take action to strengthen their oversight of patient safety. Our review has captured some of the key areas in which boards may be able to develop greater expertise, through, for example, the provision of better information and education for board members in using data to inform decision making. Our review also indicates that efforts to create effective governance for quality and patient safety remain variable and are only just beginning. Future work in this area is required, focusing on which available conceptual models provide appropriate bases for action and whether empirical studies of board oversight practices associated with good patient safety outcomes can be adequately theorized and translated across different settings. This is an exciting research agenda, with direct and serious implications for patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions in developing this article. The research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) program (grant no. 10/1007/02; project title “Effective Board Governance of Safe Care”; coapplicants R. Mannion, T. Freeman, R. Millar, and H.T.O. Davies). The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR program.

References

- Alexander JA, Lee SY. Does Governance Matter? Board Configuration and Performance in Not-for-Profit Hospitals. The Milbank Quarterly. 2006;84:733–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Weiner BJ, Succi M. Community Accountability among Hospitals Affiliated with Health Care Systems. The Milbank Quarterly. 2000;78:157–84. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Young GJ, Weiner BJ, Hearld LR. How Do System-Affiliated Hospitals Fare in Providing Community Benefit? Inquiry. 2009;46(1):72–91. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_46.01.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader BS. CQI Progress Reports: The Dashboard Approach Provides a Better Way to Keep Board Informed about Quality. Healthcare Executive. 1993;8:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader BS. Best Practices for Board Quality Committees. Great Boards. 2006 Available at http://www.greatboards.org/newsletter/reprints/Board_quality_committees_best_practices.pdf (accessed July 10, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Baker GR, Denis JL, Pomey MP, MacIntosh-Murray A. Effective Governance for Quality and Patient Safety in Canadian Healthcare Organizations: A Report to the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation and the Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Ottawa: CHSRF/CPSI; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Belmont E, Haltom CC, Hastings DA, et al. Quality in Action: Paradigm for a Hospital Board-Driven Quality Program. Journal of Health Life Sciences and Law. 2011a;24(2):95–145. [Google Scholar]

- Belmont E, Haltom CC, Hastings DA, et al. A New Quality Compass: Hospital Boards’ Increased Role under the Affordable Care Act. Health Affairs. 2011b;30(7):1282–89. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers N, Cornforth C. The Role of Corporate Governance and Boards in Organisation Performance. In: Walshe K, Harvey G, editors. From Knowing to Doing: Connecting Knowledge and Performance in Public Services. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JR, Lerner JC, Marella W. The Role for Leaders of Health Care Organizations in Patient Safety. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2007;22(5):311–18. doi: 10.1177/1062860607304743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough J, Nash DJ. Health Care Governance for Quality and Safety: The New Agenda. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2007;22(5):203–13. doi: 10.1177/1062860607301285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway J. Getting Boards on Board: Engaging Governing Boards in Quality and Safety. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2008;34(4):214–20. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran CR, Totten MK. Quality, Patient Safety, and the Board. Nursing Economics. 2010;28(4):273–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies HTO, Mannion R. Clinical Governance: Striking a Balance between Checking and Trusting. In: Smith P, editor. Reforming Health Care Markets: An Economic Perspective. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2000. pp. 247–67. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. An Organisation with a Memory. London: Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M, Leslie M, Bion J, Tarrant C. What Counts? An Ethnographic Study of Infection Data Reported to a Patient Safety Program. The Milbank Quarterly. 2012;90(3):548–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. This Is a Test. Exams for Governance Boards on Quality Measures Could Be a Way to Improve Care, Accountability in Hospitals. Modern Healthcare. 2009;39(46):6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Eickhoff K, Plowman DA, McDaniel RR. Hospital Boards and Hospital Strategic Focus: The Impact of Board Involvement in Strategic Decision Making. Health Care Management Review. 2011;36(2):145–54. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182099f6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R. The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: Stationery Office; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel A, Graydon-Baker E, Neppl C, Simmonds T, Gustafson M, Gandhi TK. Patient Safety Leadership WalkRounds. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2003;29(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam KS. A Call for Board Leadership on Quality in Hospitals. Quality Management in Health Care. 2005;14(1):18–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeschel CA, Berenholtz SM, Culbertson RA, Jin LD, Pronovost PJ. Board Quality Scorecards: Measuring Improvement. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2011;26(4):254–60. doi: 10.1177/1062860610389324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeschel CA, Holzmueller CG, Pronovost PJ. Hospital Board Checklist to Improve Culture and Reduce Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2010;36(11):525–28. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray BH, Weiss L. The Role of Trustees and the Ethics of Trusteeship: Findings from an Empirical Study. In: Jennings B, Gray BH, Sharpe VA, Fleischman AR, editors. The Ethics of Hospital Trustees. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 2004. pp. 90–133. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Potts H, Wong G, Bark P, Swinglehurst D. Tensions and Paradoxes in Electronic Patient Record Research: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Meta-narrative Method. The Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(4):729–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O, Peacock R. Storylines of Research in Diffusion of Innovation: A Meta-narrative Approach to Systematic Review. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(2):417–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Commission. Safe in the Knowledge: How Do NHS Trust Boards Ensure Safe Care for Their Patients? London: 2009a. [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Commission. Safely Does It: Implementing Safer Care for Patients. London: 2009b. [Google Scholar]

- Heenan M, Khan H, Binkley D. From Boardroom to Bedside: How to Define and Measure Hospital Quality. Healthcare Quarterly. 2010;13(1):55–60. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2013.21615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood C. Regulation inside Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons Health Committee. Patient Safety: Sixth Report 2008–2009. House of Commons. London: Stationery Office; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings B, Gray BH, Sharpe VA, Fleischman AR. The Ethics of Hospital Trustees. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Epstein AM. Hospital Governance and the Quality of Care. Health Affairs. 2010;29(1):182–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Epstein AM. Governance around Quality of Care at Hospitals That Disproportionately Care for Black Patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27(3):297–303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1880-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Epstein AM. A Survey of Board Chairs of English Hospitals Shows Greater Attention to Quality of Care Than Among Their US Counterparts. Health Affairs. 2013;32(4):677–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Li Z, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Care in U.S. Hospitals—The Hospital Quality Alliance Program. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(3):265–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang HJ, Lockee C, Bass K, Fraser I. Board Engagement in Quality: Findings of a Survey of Hospital and System Leaders. Journal of Healthcare Management. 2008;53(2):121–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang HJ, Lockee C, Bass K, Fraser I. Board Oversight of Quality: Any Differences in Process of Care and Mortality? Journal of Healthcare Management. 2009;54(1):15–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang HJ, Lockee C, Fraser I. Enhancing Board Oversight on Quality of Hospital Care: An Agency Theory Perspective. Health Care Management Review. 2011;37(2):144–53. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182224237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission. 2011 Hospital: National Patient Safety Goals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: 2011. Available at http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/HAP_NPSG_6-10-11.pdf (accessed July 16, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Joshi MS, Hines S. Getting the Board on Board: Engaging Hospital Boards in Quality and Patient Safety. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2006;32(4):179–87. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy I. Learning from Bristol: Public Inquiry into Children's Heart Surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995. London: Stationery Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kroch E, Vaughn T, Koepke M, et al. Hospital Boards and Quality Dashboards. Journal of Patient Safety. 2006;2(1):10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal Trends in Rates of Patient Harm Resulting from Medical Care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:2124–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop CB. Using Graphs to Consolidate Reports to the Board. Journal for Healthcare Quality. 1997;19(1):26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.1997.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leistikow IP, Kalkman CJ, de Bruijn H. Why Patient Safety Is Such a Tough Nut to Crack. BMJ. 2011;342:d3447. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machell S, Gough P, Naylor D, Nath V, Steward K. Putting Quality First in the Boardroom: Improving the Business of Caring. London: King's Fund; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod L. Nursing Leadership: Ten Compelling Reasons for Having a Nurse Leader on the Hospital Board. Nurse Leader. 2010;8(5):44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Marren JP, Feazell GL, Paddock MW. The Hospital Board at Risk and the Need to Restructure the Relationship with the Medical Staff: Bylaws, Peer Review and Related Solutions. Annals of Health Law. 2003;12:179–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastal MF, Joshi M, Schulke K. Nursing Leadership: Championing Quality and Patient Safety in the Boardroom. Nursing Economics. 2007;25(6):323–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreaddie M, Wiggins S. The Purpose and Function of Humour in Health, Healthcare and Nursing: A Narrative Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;61(6):584–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JA, Silow-Carroll S, Kutyla T, Stepnick LS, Rybowski LS. Hospital Quality: Ingredients for Success: Overview and Lessons Learned. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers S. Data in, Safety out: Balanced Scorecards Help the Board Make Patient Safety Their No. 1 Priority. Trustee. 2004;57(7):12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers S. Cultivating Trust: The Board-Medical Staff Relationship. Trustee. 2008;61(10):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetgen WJ. The Governing Board's Role in the Quality Agenda: An Overview. Prescriptions for Excellence in Health Care. 2009;5:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Paine LA, Baker DR, Rosenstein B, Pronovost PJ. The Johns Hopkins Hospital: Identifying and Addressing Risks and Safety Issues. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2004;30(10):543–50. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J. Moving beyond Effectiveness in Evidence Synthesis: Methodological Issues in the Synthesis of Diverse Sources of Evidence. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Methods Programme; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Powell AE, Rushmer RK, Davies HTO. A Systematic Narrative Review of Quality Improvement Models in Health Care. Edinburgh: Quality Improvement Scotland (QIS); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Prybil LD. A Perspective on Local-Level Governance in Multiunit Systems. Hospital and Health Services Administration. 1991;36:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prybil LD. Nursing Involvement in Hospital Governance. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2007;22:1–3. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prybil LD. Engaging Nurses in Governing Hospitals and Health Systems. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2009;24(January–March):5–9. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31818f55b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prybil LD. Nurses in Health Care Governance: Is the Picture Changing? Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2013;28(2):103–7. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31827efb8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prybil LD, Bardach DR, Fardo DW. Board Oversight of Patient Care Quality in Large Nonprofit Health Systems. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1062860613485407. doi: 10.1177/1062860613485407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prybil LD, Peterson R, Brezinski P, Zamba G, Roach W, Fillmore A. Board Oversight of Patient Care Quality in Community Health Systems. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2010;25(1):34–41. doi: 10.1177/1062860609352804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh M, Reinertsen J. Reducing Harm to Patients: Using Patient Safety Dashboards at the Board Level. Healthcare Executive. 2007;22(62):64–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay A, Fulop N, Fresko A, Rubenstein S. The Healthy NHS Board 2013: Review of Guidance and Research Evidence. Leeds: NHS Leadership Academy; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay A, Magnusson C, Fulop N. The Relationship between External and Local Governance Systems: The Case of Health Care Associated Infections and Medication Errors in One NHS Trust. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2010;19(6):1–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.037473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinertsen JL. Hospital Boards and Clinical Quality: A Practical Guide. Toronto: Ontario Hospital Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers M, Sowden A, Petticrew M, et al. Testing Methodological Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: Effectiveness of Interventions to Promote Smoke Alarm Ownership and Function. Evaluation. 2009;15(1):47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sandrick K. One Giant Leap for Quality. When Boards Get behind Quality Initiatives, Patient Care Benefits. Trustee. 2005;58(3):22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schyve PM. What You Can Do: The Trustee, Patient Safety, and JCAHO. Trustee. 2003;56(2):19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secretary of State. Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Allegations of Ill Treatment of Patients and Other Irregularities at the Ely Hospital, Cardiff. 1969. (Cmnd 3975). Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State of the Department of Health and Social Security by Command of Her Majesty, United Kingdom.

- Slessor SR, Crandall JB, Nielsen GA. Case Study: Getting Boards on Board at Allen Memorial Hospital, Iowa Health System. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2008;34(4):221–27. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn T, Koepke M, Kroch E, Lehrman W, Sinha S, Levey S. Engagement of Leadership in Quality Improvement Initiatives: Executive Quality Improvement Surveys. Journal of Patient Safety. 2006;2(1):2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent C. Patient Safety. London: BMJI Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wachter RM. Patient Safety at Ten: Unmistakable Progress, Troubling Gaps. Health Affairs. 2010;29(1):165–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring J, Rowley E, Dingwall R, Palmer C, Murcott T. A Narrative Review of the UK Patient Safety Research Portfolio. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2010;15(1):26–32. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ, Shortell SM, Alexander J. Promoting Clinical Involvement in Hospital Quality Improvement Efforts: The Effects of Top Management, Board, and Physician Leadership. Health Services Research. 1997;32(4):491–510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]