Abstract

Measures of genetic differentiation between populations are a useful tool for understanding the long-term dynamics of parasite communities. We followed the allele frequencies of microsatellite markers in samples taken over a period of 16 years from the CWRU laboratory strain of Schistosoma mansoni. DNA was isolated from 46 pooled or aggregated samples of adults, eggs, and cercariae and was genotyped for 14 tri- or tetranucleotide microsatellite markers. Two S. mansoni reference strains, including the strain from which the CWRU line was originally derived, were also analyzed over shorter periods of time. We observed that the long-term allele frequencies are generally stable in large populations of this parasite that utilizes both sexual and asexual reproduction. The CWRU strain, however, showed 2 periods of marked deviations from stability. These corresponded with a period of admixture from one of the reference strains and a period of genetic drift when the population size was greatly reduced. Using genetic differentiation measures we demonstrate which of the reference strains was the source of the admixture. The 2 populations show little differentiation at the point of mixture, and a new equilibrium is reached as the “migrants” become blended into the existing CWRU population. This new equilibrium was consistent with 30% admixture from the reference strain. We also observed that the allele frequencies of the different developmental stages were essentially identical. Accounting only for the intensity or prevalence of parasite populations may fail to register significant changes in population structure that could have implications for resistance, morbidity and the design of control measures.

Keywords: Schistosoma mansoni, population genetics, trematode, microsatellite, diversity, differentiation

1. Introduction

Parasites such as schistosomes pose special challenges to population genetic analyses. In both their modes of reproduction as well as their distribution they tend to violate most models used to develop many of the classic analytical approaches. In their definitive hosts schistosome reproduction is sexual although their progeny do not remain within the same infected individual, while in their intermediate snail host they undergo clonal reproduction. Furthermore, in human hosts schistosomes are distributed as highly mobile infrapopulations of a larger community, and the distribution among hosts is not random but associated with a variety of demographic characteristics such as age, sex, occupation, and socioeconomic status. Nevertheless, many of the basic concepts and analytic approaches in population genetics still apply, and Balloux et al. (2003) suggested that the structure of such partially clonal populations differs little from strictly sexual organisms.

While the behavior of natural populations is complex, laboratory populations of the parasite can provide a simplified model for examining schistosome population dynamics. We have shown that natural aggregates of excreted Schistosoma mansoni eggs from humans can be used to determine allele frequencies from individual infrapopulations, and this method can be used to widely sample individuals in a community (Blank et al., 2009). The interpretation of such data can be guided by the observation of population dynamics established in laboratory populations.

Laboratory strains of the parasite S. mansoni are the primary source for vaccine studies and other investigations in this field. These strains are maintained by transmission between rodents and laboratory adapted snails (Lewis et al., 2008), and are less diverse than natural populations due to founder effects and genetic drift (Stohler et al., 2004). There is little information on the genetic structure of S. mansoni laboratory strains or on the stability of microsatellite markers in this organism. Between 1961 and 2000 a life cycle of S. mansoni was maintained at Case Western Reserve University, and samples from this laboratory strain were collected from 1984 to the end of the program in 2000. We used a set of 14 microsatellite markers to genotype the aggregated parasites from this life cycle in order to study changes in marker stability and population structure over this 16 year period.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. S. mansoni life cycles and samples

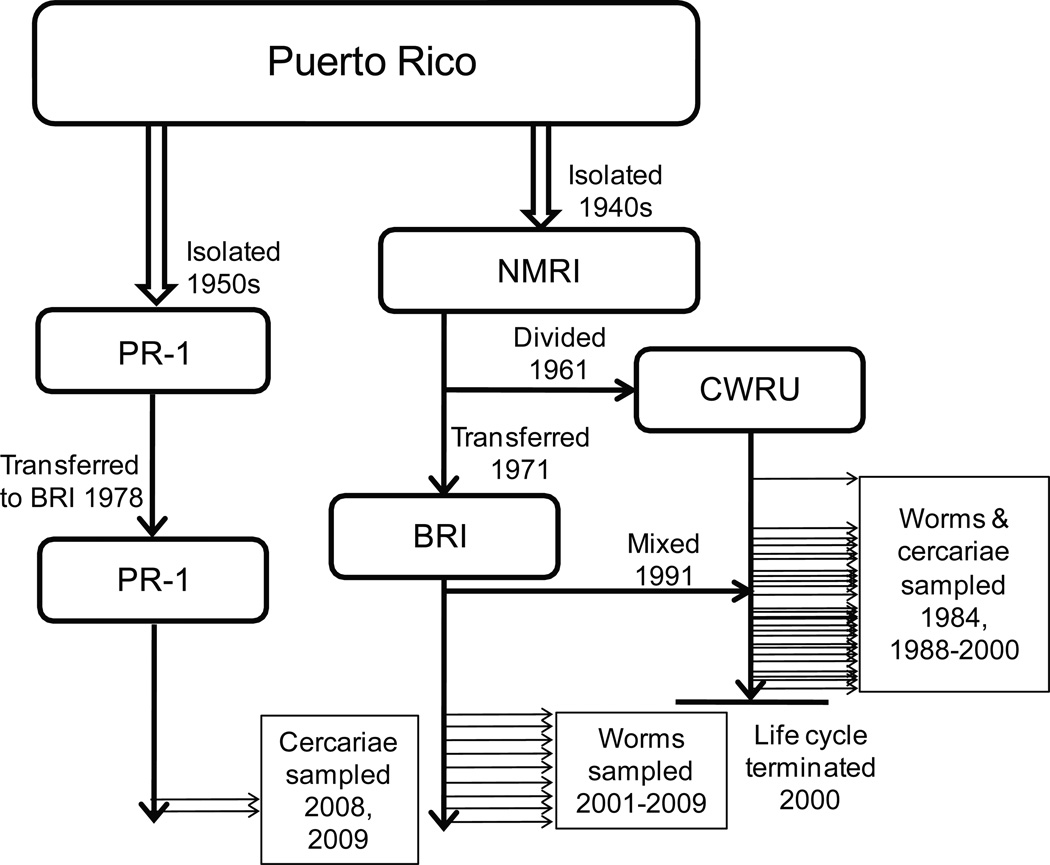

The S. mansoni laboratory strain at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) was obtained in 1961 from the Naval Medical Research Institute (NMRI) strain (of Puerto Rican origin) and maintained by passage through Biomphalaria glabrata snails and CF1 mice (Figure 1). Until December 1997, approximately 120 snails per week were infected with miracidia hatched from S. mansoni eggs collected from the homogenized livers of 10 infected mice, and 50 mice per week were infected with approximately 200 cercariae each. In late 1991 a collapse in the snail population at CWRU prompted supplementation of the life cycle with infected snails from the Biomedical Research Institute (BRI). Over several months, these newly added parasites were integrated with the remaining CWRU population which was still maintained in mice. Beginning in 1998, the number of mice used as definitive hosts for the strain was reduced to 5 per month. From March 1984 to July 2000, samples of different life cycle stages were collected at various times and stored at −80°C. In this study, 46 such samples (22 of cercariae, 23 of worms and 1 egg sample) were analyzed.

Figure 1.

Schistosoma mansoni laboratory strain histories. The NMRI strain was isolated from Puerto Rican school children in Washington, D.C. The PR-1 strain was originally collected in Puerto Rico. Horizontal arrows indicate transfers or sample collections.

The original NMRI life cycle was transferred to the BRI in 1971 and has since been maintained there in albino B. glabrata snails and Swiss Albino mice (Lewis et al., 2008). Adult worm samples from the NMRI strain were collected by perfusion from approximately 45 mice that had each been exposed to 180–200 cercariae shed from 40–50 infected snails. Nine yearly samples from 2001 to 2009 were examined. For comparison, two samples of cercariae from a second BRI strain (PR-1) were also shed in 2008 and 2009 from approximately 200 infected snails that had been reared to patency at CWRU. This strain was originally collected from infected snails at Arecibo, Puerto Rico, in 1950 and was established at BRI in 1978 (Figure 1). For the remainder of this article, the NMRI origin strains will be referred to with the initials of the institutions at which they were maintained (‘CWRU’ or ‘BRI’), while the PR-1 strain maintained at BRI will continue to be referred to as ‘PR-1’.

DNA was extracted from the worms and cercariae using a standard proteinase K/phenol:chloroform extraction protocol (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). DNA was resuspended in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5 to a standard concentration of 25 ng/μL.

2.2. Microsatellite genotyping

We selected 14 tri- or tetranucleotide microsatellites (Curtis et al., 2001; Rodrigues et al., 2002; Silva et al., 2006; Rodrigues et al., 2007) based on ease of amplification and readability in the CWRU population. One newly developed marker (1F8A) was also included. Primers for locus 1F8A (F: GGCTTCAGTCGTCGTGTTC, R: GCTTCTTCGTTGCCACACTC) were chosen using MSATCOMMANDER (Faircloth, 2008) from a bacterial artificial chromosome sequence generated by the S. mansoni genome project (Berriman et al., 2009). For all loci, the forward primer was labeled with a fluorescent dye (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microsatellite locus information

| Pooling Group |

Locus |

Reference |

Dye used | Repeat unit | Size Range (nt) |

Alleles Observed (Gene Diversity)* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CWRU | BRI | PR-1 | ||||||

| 1 | SMMS2 | Silva et al., 2006 | FAM | CAAA | 212 – 235 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (2.0) |

| SMMS13 | Silva et al., 2006 | ROX | ATT | 183 – 189 | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) | |

| SMMS16 | Silva et al., 2006 | HEX | ATT | 215 – 227 | 5 (3.9) | 5 (4.1) | 3 (1.1) | |

| 2 | SMMS3 | Silva et al., 2006 | FAM | AAT | 179 – 207 | 7 (4.1) | 5 (1.7) | 6 (3.0) |

| SMMS17 | Silva et al., 2006 | HEX | AAT | 289 – 298 | 4 (3.0) | 4 (2.4) | 2 (1.1) | |

| SMMS18 | Silva et al., 2006 | JOE | AAT | 204 – 228 | 8 (4.0) | 5 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | |

| SMMS21 | Silva et al., 2006 | ROX | ATT | 177 – 180 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | |

| 3 | SmBR-8 | Rodrigues et al., 2007 | FAM | AAT | 204 – 237 | 12 (10.2) | 9 (7.6) | 11 (6.8) |

| SmBR-13 | Rodrigues et al., 2007 | HEX | CTAT | 202 – 246 | 12 (8.4) | 6 (3.1) | 8 (2.7) | |

| SMD43 | Curtis et al., 2001 | ROX | GATA | 145 – 181 | 7 (3.4) | 6 (3.6) | 4 (2.0) | |

| SMDO11 | Curtis et al., 2001 | ROX | GATA | 314 – 394 | 17 (6.6) | 7 (3.1) | 5 (2.1) | |

| 4 | 13TAGA | Rodrigues et al., 2002 | FAM | GATA | 103 – 143 | 9 (4.1) | 8 (3.0) | 3 (1.5) |

| SMDA23 | Curtis et al., 2001 | NED | GATA | 197 – 233 | 7 (6.3) | 6 (1.8) | 3 (2.1) | |

| 1F8A | This study | VIC | ATT | 151 – 166 | 6 (3.4) | 4 (2.2) | 3 (1.2) | |

| Total Alleles (Average Diversity) | 101 (3.8) | 71 (2.6) | 55 (2.0) | |||||

Allele counts and diversity measures are maximum values over the observed time.

Alleles with a frequency of greater than 1% at a given time point were counted.

Duplicate PCR amplifications were performed in 15 µl volumes with 75 ng DNA, 4.5 pmol of each primer, 6 nmol dNTPs, and 0.6 units of DyNAzyme II DNA Polymerase (Finnzymes, Inc., Woburn, MA) in 1x reaction buffer supplemented with 25 mM KCl and 1 mM MgCl2. The reactions were carried out in duplicate on an MJ Research PTC thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA) using the following cycling conditions: an initial denaturation step at 94°C; 35 cycles at 94°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 50°C for 1 minute (45°C for SMMS2), and 72°C for 15 seconds. Cycling was followed by a final extension at 72°C for 20 minutes.

The PCR products from each sample were pooled into groups of three or four primer sets (Table 1) and analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Cornell University Life Sciences Core Laboratories Center, Ithaca, NY). Fragment sizes and peak heights were measured using Peak Scanner software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) and allele frequencies were determined based on peak heights as previously described (Blank et al., 2009).

2.3 Data analysis

Average sample allele frequencies of duplicate amplifications for each locus were multiplied by the estimated number of individuals in each sample (~200) to obtain the allele counts. Gene diversity in terms of effective number of alleles at each locus was calculated as 1 / the sum of squares of allele frequencies (Kimura and Crow, 1964). FST was calculated using Arlequin v3.11 (Excoffier et al., 2005). Because the maximum possible FST between populations (FST(max)) tends toward zero as the number of alleles increases (Long and Kittles, 2003), FST may not adequately represent population differentiation when markers are highly polymorphic. Therefore, we also calculated the standardized index, F’ST, where F’ST = FST / FST(max). FST(max) was calculated by recoding the alleles from each sample as unique in the Arlequin input file (Meirmans, 2006). Differentiation was also measured as Jost’s D (Chao et al., 2008; Jost, 2008) using the program SPADE (Chao and Shen, 2003). Mean differentiation values across loci were reported. The interval rate of differentiation was calculated as pairwise D between consecutive samples divided by the number of weeks between the sampling points.

3. Results

3.1 Allele frequencies and genetic diversity

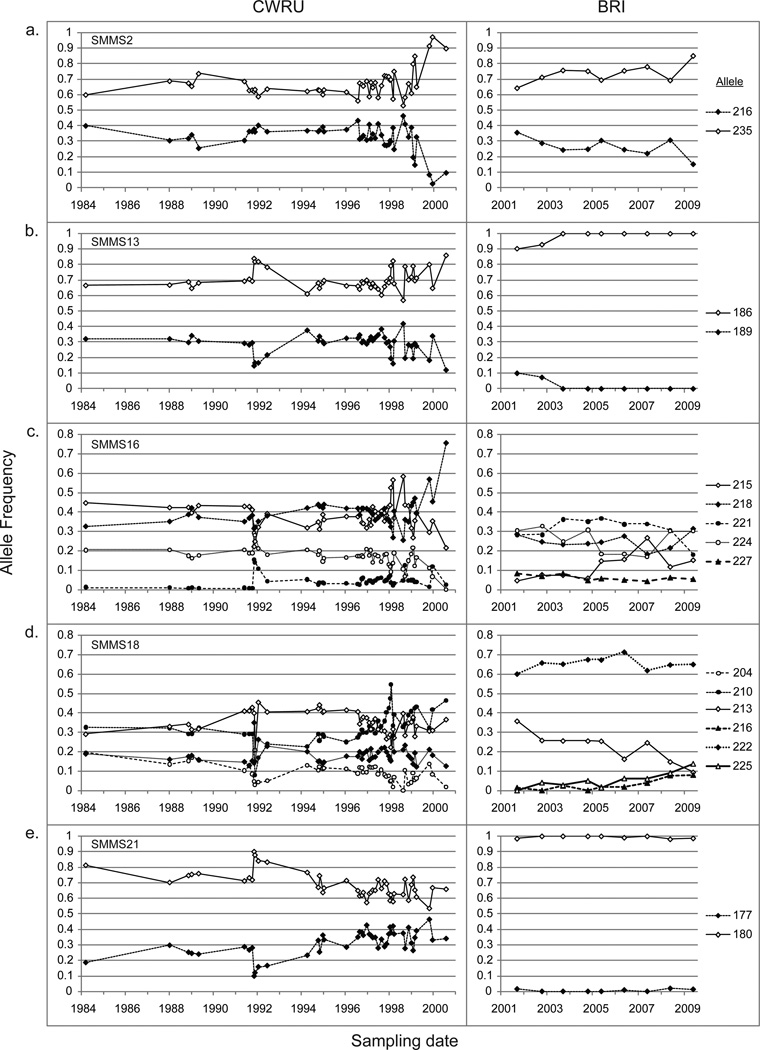

Over the sampling period, the CWRU strain demonstrates greater diversity with a larger number of alleles at the loci examined (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 1; Table 1). Both the BRI and PR-1 strains were fixed at a single allele at the SMMS21 locus (Figure 2e, Table 1), while fixation of locus SMMS13 was observed to occur in the BRI strain between the 2002 and 2003 samples (Figure 2b). The allele frequencies for both strains show considerable stability over the intervals of observation, except for 2 periods for the CWRU strain, corresponding to 2 recognizable events. The first occurs in late 1991 when a collapse in the infected snail population at CWRU prompted supplementation of the life cycle with infected snails from an externally maintained strain. The second corresponds to a period where the CWRU life cycle was maintained at the lowest population size possible to reduce costs, so that 5 mice per month were infected rather than the 50–100 per week for much of the preceding period.

Figure 2.

Major alleles at loci SMMS2 (a), SMMS13 (b), SMMS16 (c), SMMS18 (d), and SMMS21 (e) of the Schistosoma mansoni strain NMRI populations maintained at CWRU and BRI. Alleles with a frequency of greater than 5% at least once over the sampling period are presented.

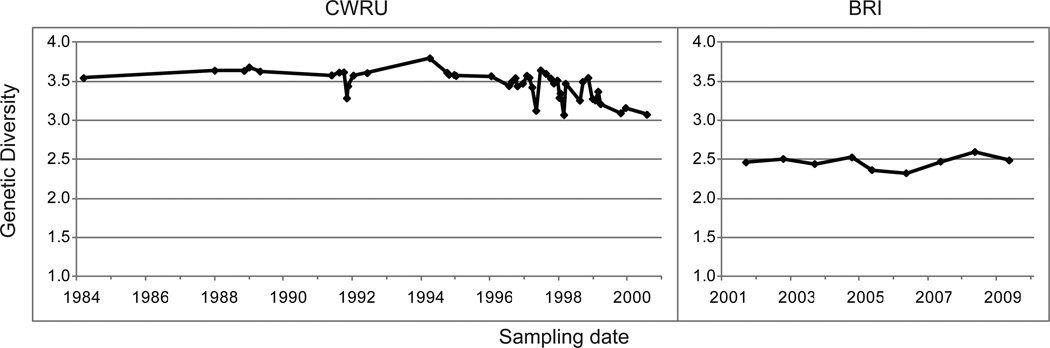

The average genetic diversity across loci was calculated for each sample in the CWRU and BRI strains (Figure 3; individual locus diversities are shown in Supplemental Figure 2). Compared with BRI, a greater level of diversity is observed in the CWRU strain although a steady decline is seen after 1998, corresponding with the reduction in population size.

Figure 3.

Genetic diversity in the CWRU and BRI populations. Diversity values were averaged across loci for each sample.

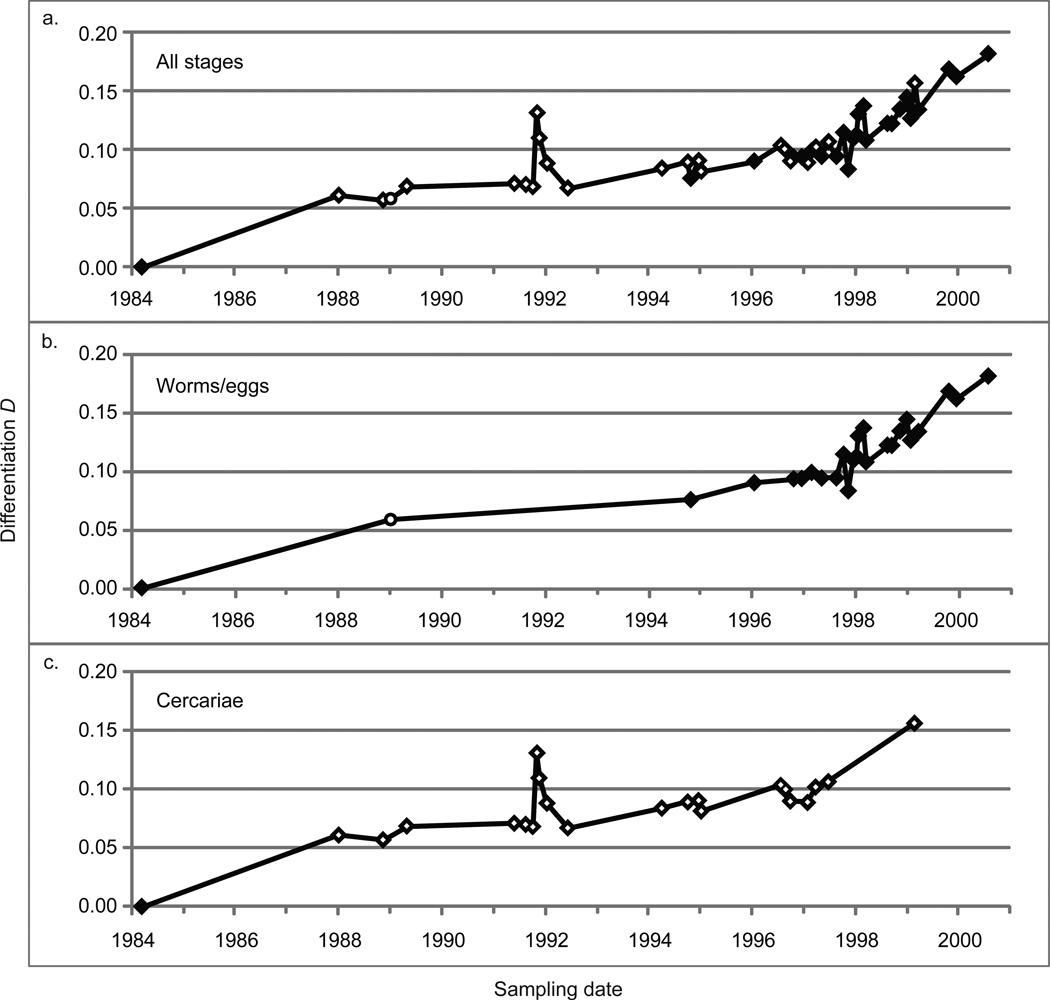

3.2 Differentiation within populations

Longitudinal genetic differentiation within and between populations was measured by calculating pairwise values for FST, F’ST, and D relative to the earliest sample from each population. The differentiation of the CWRU population reflects the same 2 events apparent with the individual allele frequencies (Figure 4a). Between 1988 and 1991, there was little differentiation in the population as measured by any of the indices. For the FST, the abrupt differentiation spike is followed by a return to the baseline. The other indices show small continued increases. After 1998, the rate of differentiation increases for all indices. The BRI population is more stable for the 9 years sampled with all indices less than 0.05, except for the F’ST in 2007. Whereas the indices show consistently that FST < D < F’ST for the CWRU strain, the FST and D are indistinguishable for BRI. The two PR-1 samples analyzed showed negligible differentiation, with FST and D values of 0.02 and F’ST of 0.04.

Figure 4.

Differentiation of Schistosoma mansoni NMRI populations at each sampling point. (a) Comparison of long-term intrapopulation differentiation with the indices D, FST, and F’ST calculated pairwise against the first sample collected from the respective population (3/16/1984 for CWRU, 9/26/2001 for BRI). (b) Pairwise rate of differentiation. D/week between proximal pairs of samples using a sliding window approach. (c) Interpopulation differentiation using D calculated pairwise against the first sample collected from other populations (3/16/1984 for CWRU, 9/26/2001 for BRI, 4/15/2008 for PR-1).

To correct for the irregular time intervals between samples we also performed a pairwise analysis which represents rates of differentiation between consecutive samples (Figure 4b). This again reveals the same 2 clear periods in the CWRU timeline where rates of change were markedly different from the baseline, while the BRI strain shows little change over the 9 years sampled.

3.3 Differentiation between populations

D between the CWRU and BRI strains fell rapidly from 0.35 to <0.05 with the 11/7/1991 sample (Figure 4c) and returned to a stable elevated level over the next 3 samples (a period of 31 weeks), although differentiation remained below pre-1991 levels until termination of the life cycle in 2000. The differentiation between CWRU and PR-1 remained high (> 0.50) throughout this period and across the entire sampled period without marked changes. Although records of which parasite strain was used to supplement the CWRU life cycle were unavailable for this analysis, the dramatic reduction in differentiation between CWRU and BRI at this time demonstrates that the BRI strain and not PR-1 was the source. Further evidence for this is the appearance of new alleles seen after 1991 in the CWRU strain which are also present in the current BRI strain (Figure 2c, SMMS16 allele 221; Supplemental Figure 1, SMMS3 allele 189; SMD011 allele 358; 13TAGA allele 119; 1F8A allele 154). We estimated the contribution of the second population to the CWRU population by calculating the proportion of migrants needed to produce the observed reduction in D. Based on the degree of diminished differentiation between the CWRU and BRI strains, we calculate that 30% of the post-1991 CWRU strain originated from the BRI population (see Supplement 1).

3.4 Differentiation by developmental stage

In the CWRU strain, the available samples were composed of cercariae, adults and one sample of eggs. To determine whether allele frequencies observed in the larval stage reflect those seen in adults, we examined intrapopulation differentiation among different life cycle stages (Figure 5). Differentiation between the first CWRU sample and samples from adults or eggs (Figure 5b) and cercariae (Figure 5c) collected near the same time period shows little difference between D in different life cycle stages.

Figure 5.

D calculated pairwise between each sample collected from the CWRU population vs. the first sample from that population (3/16/1984). (a) All developmental stages. (b) Egg and adult worm samples. (c) Cercarial samples. Closed diamond – Adult worms; Open circle – Eggs; Open diamond – Cercariae.

4. Discussion

In large, closed laboratory populations of S. mansoni, we show that microsatellite allele frequencies are stable over the long-term as would be predicted by the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The length of observation is especially great considering that for laboratory populations of S. mansoni, 16 years represents > 100 generations. The mixture of the CWRU and BRI life cycles represents a migration event that is evident in the allele frequency profiles (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 1) and the differentiation indices (Figure 4). As the population size of the CWRU life cycle was reduced, we also saw the effects of genetic drift in these profiles with a characteristic decrease in diversity. This approach using laboratory strains has empirically established some of the parameters and expectations of a stable transmission cycle in nature.

The differences in genetic diversity between the CWRU and BRI strains could be attributed to differences in the sizes of the populations maintained at the two institutions, despite their common origin. For most of its duration, the CWRU strain was maintained by infection of more than 100 snails, while 50 or fewer snails were infected per generation at BRI. The smaller pool of miracidia would be more susceptible to genetic drift. When the number of mice used at CWRU was reduced in 1998, the rapid decline in the population of breeding worms introduced the bottleneck seen in Figure 3.

The sampling strategy for this study utilized pooled or aggregated samples based on our own and others’ experiences that these samples provide an efficient and representative estimate of allele frequencies (Blank et al., 2009; Hanelt et al., 2009). A key condition for any pooling experiment is that the pool be unbiased. Since total DNA was analyzed from all of the recovered adult organisms in different cohorts of the life cycle, the only bias could come from the failure to collect a particular subpopulation or non-random heterogeneity in adult worm size between cohorts. The other life cycle stages were obtained by isolating all of the eggs possible from liver or intestines of infected animals and all of the shed cercariae. Selection bias is unlikely to occur in this process, and indeed this did not appear to be the case as little difference is seen between stages (Figure 5). There likewise did not appear to be significant bias in egg hatching or snail infection since allele frequencies for cercariae were comparable to adults during similar periods.

The use of pooled or aggregate samples allowed diversity estimates to be based on large sample sizes, better corresponding to the “all individuals” sampling strategy recommended by De Meeûs et al. (2006) for organisms with a component of asexual reproduction in their developmental program. The results using this approach show marker stability over many generations when the environment is stable and accurately reflects events occurring in the life history of laboratory strains. There is significant efficiency in this approach, and the efficiency gained permits examination of a large number of infrapopulations. This will be needed to begin to understand how the parasite population is structured relative to households, age, sex, occupation, socio-economic conditions, length of residence, place of residence, water contact sites and the many other important factors that may govern the distribution of genotypes among individual hosts. Measuring allele frequencies in infrapopulations permits observation of significant changes in the structure of field populations that could have implications for resistance, morbidity, and the design of control measures. These changes may not be apparent when monitoring only for the intensity or prevalence of parasite populations. One potential drawback for use of pooled samples, however, is that null alleles are difficult to recognize and if present may result in overestimation of genetic distance and differentiation (Chapuis and Estoup, 2007).

There has been long-standing concern over the validity of various measures of differentiation, in particular that FST and related indices tend to underestimate differentiation when gene diversity is high (Long and Kittles, 2003; Meirmans, 2006; Jost, 2008), a characteristic of microsatellite loci. We compared 3 commonly used indices in our analyses, all of which showed the same trends in the differentiation of the S. mansoni populations studied, although the underestimation of differentiation by FST could reduce its sensitivity to detect genetic structure in populations.

We also found that allele frequencies in laboratory strains did not depend on the life cycle stage used. In nature, however, there is likely to be a difference between the allele frequencies in different component compartments. Snails are unlikely to be presented with the full range of genotypes present in the human populations since certain groups of individuals, typically children, have higher infection intensities and are more likely to be responsible for contaminating water sources. In closed systems, if the samples are large or comprehensive, allele frequencies are preserved among the life cycle stages unless the system is perturbed. The demonstrated laboratory strain equilibrium for S. mansoni provides a context for deviations found in field populations of parasites due to man-made pressures, such as mass treatment, or other ecological disturbances.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Stein and Rajeev Mehlotra for helpful comments and discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant AI41680 and NIAID Contract N01-A1-30026.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data associated with this article

References

- Balloux F, Lehmann L, de Meeûs T. The population genetics of clonal and partially clonal diploids. Genetics. 2003;164:1635. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriman M, Haas BJ, LoVerde PT, Wilson RA, Dillon GP, Cerqueira GC, Mashiyama ST, Al-Lazikani B, Andrade LF, Ashton PD. The genome of the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. Nature. 2009;460:352–358. doi: 10.1038/nature08160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank WA, Reis EAG, Thiong’o FW, Braghiroli JF, Santos JM, Melo PRS, Guimarães ICS, Silva LK, Carmo TMA, Reis MG, Blanton RE. Analysis of Schistosoma mansoni population structure using total fecal egg sampling. Journal of Parasitology. 2009;95:881–889. doi: 10.1645/GE-1895.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao A, Shen TJ. SPADE (Species Prediction And Diversity Estimation) 2003 Program and User’s Guide published at http://chao.stat.nthu.edu.tw.

- Chao A, Jost L, Chiang SC, Jiang YH, Chazdon RL. A two-stage probabilistic approach to multiple-community similarity indices. Biometrics. 2008;64:1178–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapuis MP, Estoup A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Molecular biology and evolution. 2007;24:621. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis J, Sorensen R, Page L, Minchella D. Microsatellite loci in the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni and their utility for other schistosome species. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2001;1:143–145. [Google Scholar]

- De Meeûs T, Lehmann L, Balloux F. Molecular epidemiology of clonal diploids: a quick overview and a short DIY (do it yourself) notice. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2006;6:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin ver. 3.0: An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth BC. MSATCOMMANDER: detection of microsatellite repeat arrays and automated, locus-specific primer design. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2008;8:92–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanelt B, Steinauer ML, Mwangi IN, Maina GM, Agola LE, Mkoji GM, Loker ES. A new approach to characterize populations of Schistosoma mansoni from humans: development and assessment of microsatellite analysis of pooled miracidia. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2009;14:322–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost L. GST and its relatives do not measure differentiation. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:4015–4026. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2008.03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Crow JF. The number of alleles that can be maintained in a finite population. Genetics. 1964;49:725–738. doi: 10.1093/genetics/49.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis FA, Liang Y-S, Raghavan N, Knight M. The NIH-NIAID Schistosomiasis Resource Center. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2008;2:e267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JC, Kittles RA. Human genetic diversity and the nonexistence of biological races. Human Biology. 2003;75:449–472. doi: 10.1353/hub.2003.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meirmans PG. Using the AMOVA framework to estimate a standardized genetic differentiation measure. Evolution. 2006;60:2399–2402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues NB, LoVerde PT, Romanha AJ, Oliveira G. Characterization of new Schistosoma mansoni microsatellite loci in sequences obtained from public DNA databases and microsatellite enriched genomic libraries. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97(S1):71–75. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000900015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues NB, Silva MR, Pucci MM, Minchella DJ, Sorensen R, LoVerde PT, Romanha AJ, Oliveira G. Microsatellite-enriched genomic libraries as a source of polymorphic loci for Schistosoma mansoni. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2007;7:263–265. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Silva LK, Liu S, Blanton RE. Microsatellite analysis of pooled Schistosoma mansoni DNA: an approach for studies of parasite populations. Parasitology. 2006;132:331–338. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005009066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohler RA, Curtis J, Minchella DJ. A comparison of microsatellite polymorphism and heterozygosity among field and laboratory populations of Schistosoma mansoni. International Journal for Parasitology. 2004;34:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.