Abstract

The functional role of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) signaling in cardiomyocytes is not entirely understood but it was linked to an increased propensity for triggered activity. The aim of this study was to determine how InsP3 receptors can translate Ca2+ release into a depolarization of the plasma membrane and consequently arrhythmic activity. We used embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (ESdCs) as a model system since their spontaneous electrical activity depends on InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release. [InsP3]i was monitored with the FRET-based InsP3-biosensor FIRE-1 (Fluorescent InsP3 Responsive Element) and heterogeneity in sub-cellular [InsP3]i was achieved by targeted expression of FIRE-1 in the nucleus (FIRE-1nuc) or expression of InsP3 5-phosphatase (m43) localized to the plasma membrane. Spontaneous activity of ESdCs was monitored simultaneously as cytosolic Ca2+ transients (Fluo-4/AM) and action potentials (current clamp). During diastole, the diastolic depolarization was paralleled by an increase of [Ca2+]i and spontaneous activity was modulated by [InsP3]i. A 3.7% and 1.7% increase of FIRE-1 FRET ratio and 3.0 and 1.5 fold increase in beating frequency was recorded upon stimulation with endothelin-1 (ET-1, 100 nmol/L) or phenylephrine (PE, 10 µmol/L), respectively. Buffering of InsP3 by FIRE-1nuc had no effect on the basal frequency while attenuation of InsP3 signaling throughout the cell (FIRE-1), or at the plasma membrane (m43) resulted in a 53.7% and 54.0% decrease in beating frequency. In m43 expressing cells the response to ET-1 was completely suppressed. Ca2+ released from InsP3Rs is more effective than Ca2+ released from RyRs to enhance INCX. The results support the hypothesis that in ESdCs InsP3Rs form a functional signaling domain with NCX that translates Ca2+ release efficiently into a depolarization of the membrane potential.

Introduction

In cardiac muscle the expression of inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptors (InsP3R) is most abundant during early development [1], [2]. In embryonic as well as neonatal cardiomyocytes the presence of all three InsP3R isoforms has been documented with the most prominent appearance of InsP3R1 and InsP3R2 [3], [4]. At embryonic and neonatal stages of differentiation, immunostainings indicate that InsP3Rs pre-dominantly locate to the nuclear envelope [4]–[6]. Receptor mediated Gq-protein stimulation of these cells results in InsP3 production and concomitantly Ca2+ release events that occurred mainly at the nuclear envelope [4], [7], [8]. The functional role of InsP3Rs in the developing myocytes is not well understood, but in the embryonic heart tube, mouse and human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and human iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes a role of InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release in the generation of spontaneous electrical activity has been demonstrated [9]–[12].

In contrast to the abundance of InsP3Rs in the early developmental stages, their expression decreases towards adulthood; However, in the adult atrial [13] and ventricular muscle of rat [14], cat [15], and rabbit [16] the expression of InsP3R2 isoforms was demonstrated. In atrial myocytes its distribution is homogeneous throughout the cell, whereas in ventricular myocytes a prevalence in the nuclear envelope (rat) [14] and the dyadic junctions (mouse) [17] was reported. During excitation-contraction coupling in the adult cardiac muscle, Ca2+ is released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum mainly through the ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2), which is expressed 50 fold higher than InsP3Rs. In contrast InsP3R-mediated signaling has been linked to excitation-transcription coupling. Activation of nuclear InsP3Rs was sufficient for the activation and translocation of the transcription factor HDAC that remained unresponsive to beat-to-beat changes in [Ca2+]i [18]. Nevertheless, despite the comparably low expression levels, InsP3Rs play a role in the induction of cardiac arrhythmia. Stimulation of InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release results in increased spark frequency, positive inotropy, and an increase in arrhythmic spontaneous activity in atrial and ventricular myocytes [15], [16], [18]–[21]. As indicated by these studies, the amount of InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release appears low and may be more relevant as a facilitator of Ca2+ release from RyRs thus contributing indirectly to excitation-contraction coupling.

The sub-cellular location of InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release could critically influence its function. Whereas sub-sarcolemmal Ca2+ release can depolarize the membrane by activation of sodium calcium exchange (NCX), Ca2+ released at the nuclear envelope might have a higher likelihood to be removed by SERCA [19], [21]. The functional differences between spatially distinct Ca2+ signaling events are very pronounced in ESdCs. Localized Ca2+ release events through RyRs (sparks) can be frequently monitored throughout the ESdC, whereas localized release events through InsP3Rs (puffs) are seldom identified [8], [9]. Nonetheless, sparks are insufficient to maintain spontaneous activity, whereas InsP3 mediated Ca2+ release can sustain spontaneous activity even after depletion of the RyR operated Ca2+ stores or in RyR2 deficient ESdCs [9], [22].

We used ESdCs as a model to test the hypothesis that InsP3Rs close to the plasma membrane form functional signaling domains with NCX and that, in contrast to cytoplasmic or nuclear InsP3Rs, their Ca2+ release can be efficiently translated into INCX and a depolarization of the membrane potential (Vm). For this purpose we determined the effect i. of InsP3R-mediated release on INCX and ii. of spatial inhomogeneities in InsP3 concentration on spontaneous activity [20].

Materials and Methods

The culture of mouse embryonic stem cells (mES) of the cell line CMV (Specialty Media; Phillipsburg, NJ, USA), their differentiation into cardiomyocytes and use for laser scanning confocal microscopy are described in detail elsewhere [9], [23].

FIRE-1 construct

As previously described [24] the FIRE-1 InsP3 biosensor was assembled using the InsP3R ligand-binding domain terminally fused with enhanced CFP and YFP at the amino and carboxyl termini, respectively. In FIRE-1 transfected COS-1 cells, rat neonatal, adult cat ventricular myocytes and ESdCs (Data S1) FIRE-1 exhibited comparable dynamic range and a 10% increase in donor (CFP) fluorescence upon bleaching of YFP, indicative of FRET [24].

FIRE-1nuc construction

The FIRE-1 indicator was targeted to the nucleus by insertion of a triplet tandem of the SV40 large T-antigen nls using the following oligonucleotides: (sense: GGCTCGAGATCCAAAAAAGAAGAGAAAGGTAGATCCAAAAAAGAAGAGAAAGGTAGATCCAAAAAAGAAGAGAAAGGTATCTCGAAGG and antisense: CCCTCGAGATACCTTTCTCTTCTTTTTTGGATCTACCTTTCTCTTCTTTTTTGGATCTACCTTTCTCTTCTTTTTTGGATCTCGAGCC). The oligonucleotides were mixed and annealed by incubation at 90°C for 5 minutes and then cooling to room temperature, followed by digestion with Xho I and ligation into similarly digested FIRE-1 plasmid [24]. Expression and nuclear localization were verified in transiently transfected COS-1 cells by Western blotting with an IP3R1 specific amino-terminal antibody (T1NH; data not shown) and direct visualization with fluorescence microscopy. The insert harboring the FIRE-1nuc coding region was excised with Bgl II and ligated into Bgl II digested pShuttle-CMV vector (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA) for adenoviral production.

m43 construction

The coding region of the mouse 43 kDa inositol polyphosphate 5′-phosphatase (m43) with N-terminal FLAG-tag from pcDNA3 (kindly provided by Dr. Elizabeth A. Woodcock, Baker Heart Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) was amplified by PCR using the following primers (sense: CGGGTCGACCCACCATGGACTACAAGGACGAC and antisense: GCCGTCGACTCACTGCACGACACAACA). The PCR product was digested with Sal I, ligated into similarly digested pCMV-5 vector, and expression was verified in COS-1 cells by transient transfection and Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibody (Affinity BioReagents) (Figure S2). The FLAG-tagged m43 coding region was excised with Sal I and ligated into Sal I digested pShuttle-CMV vector (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA) for adenoviral production.

FIRE-1nuc and m43 adenovirus production

The adenoviruses were created using the commercially available AdEasyTM XL adenoviral vector system kit (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA). Briefly, the bacterial cell line BJ5183-AD-1, pre-transformed with the plasmid pAdEasy-1 was used for in vivo homologous recombination with either pShuttle-CMV-m43 or pShuttle-CMV-FIRE-1nuc. The pAdEasy-1-m43 or pAdEasy-1-FIRE-1nuc insert containing plasmids were separately transformed into DH5α and produced in bulk. Purified pAdEasy-1-m43 or pAdEasy-1-FIRE-1nuc was used to transfect AD-293 cells for virus amplification. Both viruses were plaque-purified, amplified, CsCl gradient-purified, and stored at −80°C.

Adenoviral transduction and FRET measurements

24 hours post plating, dissociated ESdCs were transduced with recombinant replication-deficient adenovirus carrying sequence for either the InsP3 biosensor FIRE-1 [24], FIRE-1nuc (FIRE-1 sequence plus 3 tandem nuclear localization signals (3 tandem-DPKKKRKV)), or FLAG tagged m43 phosphatase [25]. After overnight incubation at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1–10 the media was replaced. Changes in fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between the cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) and the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) were measured by laser scanning confocal microscopy. CFP was excited with a 440 nm diode laser. CFP and YFP emissions were measured at 488 (F 488) and >560 nm (F 560), respectively. Changes in InsP3 activity are defined as the relative change in the background corrected ratio of F 560/F 488. To obtain a reliable reproducible readout for the changes induced by the pharmacological agents, the fluorescence was determined after 3 min of superfusion. The change was then quantified as the average fluorescence over the time period of 5 min. The experiments were conducted at room temperature. FRET between CFP and YFP was confirmed by photobleaching of the accepter molecule (YFP; Figure S1).

Chemicals and statistics

Endothelin-1 (ET-1), phenylephrine (PE), and caffeine were diluted in H2O, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), U73122 and U73343 were dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and further diluted >1,000 fold for experiments. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma. Results are presented as mean ± SEM and n represents the number of experiments. Statistical differences between two groups were analyzed by student's t-test and considered significant at P<0.05. Multiple comparisons were performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significant differences between the groups were identified with the Tukey HSD Test indicating significance at P<0.05. A detailed description of the confocal imaging, electrophysiological recordings, and immunocytochemistry can be found in Data S1.

Results

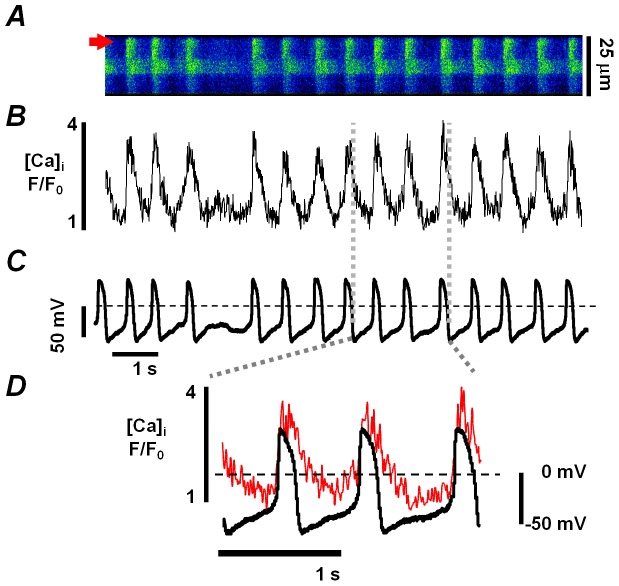

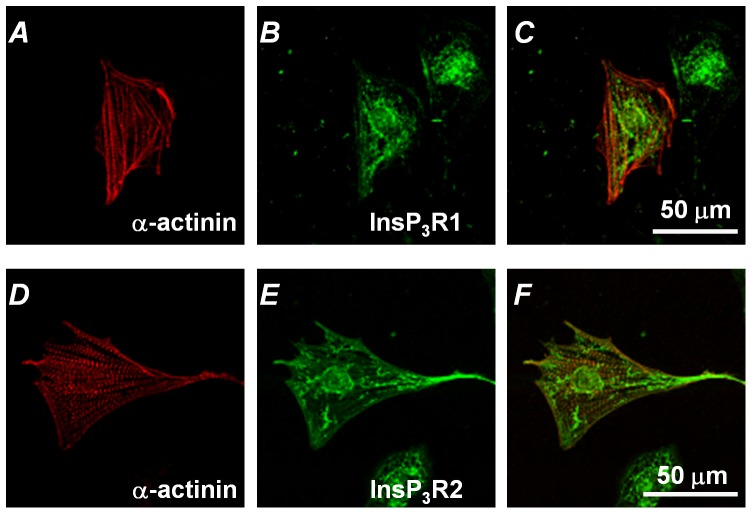

In our previous study we demonstrated that InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release plays a critical role in the generation of spontaneous activity in ESdCs [9]. To determine whether the changes in [Ca2+]i correlate with changes in membrane voltage (Vm) we recorded action potentials (APs) in Fluo-4/AM loaded ESdCs with the perforated patch technique. As shown in Fig. 1, changes in [Ca2+]i closely correlated with changes in Vm showing a clear increase in basal [Ca2+]i during the diastolic depolarization. This increase in [Ca2+]i was spatially homogeneous and did not correlate with a specific location inside the cell e.g. the nuclear envelope [26] or sub-sarcolemmal space [27]. To determine the location of InsP3Rs in ESdCs, cells were stained with antibodies against InsP3Rs type-1 and type-2. As shown in Fig. 2, ESdCs stained positive for both InsP3R isoforms. Pronounced peri-nuclear staining was identified, together with extensive endoplasmic reticulum staining throughout the cell that extended to the plasma membrane. This localization pattern suggests that InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release is not restricted to the nuclear envelope.

Figure 1. Interplay between spontaneous APs and [Ca2+]i in ESdCs.

Confocal line scan (A) and corresponding F/F0 plot (B) in a 17 day old ESdC with simultaneous measurement of changes in Vm (C). Spontaneous action potentials (APs) are recorded that correlate in time with Ca2+ transients. D: Superposition of Ca2+ transients and APs clearly show an increase in [Ca2+]i in the late phase of the diastolic depolarization.

Figure 2. InsP3 receptor isoform expression in ESdCs.

Dissociated ESdCs (d10–11) were stained for α-actinin (A, D), InsP3R1 (B) and InsP3R2 (E). C,F: Superposition of α-actinin and InsP3R staining.

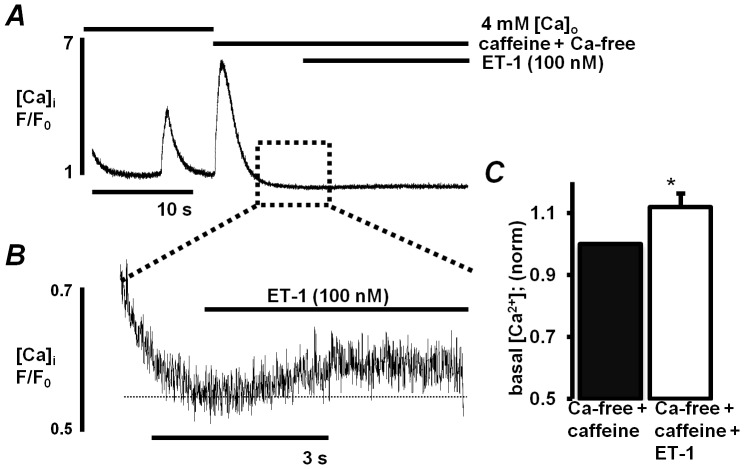

ESdCs express RyRs and caffeine induced Ca2+ transients have been recorded already when the cells first develop spontaneous activity [9], [28]. To evaluate whether RyRs and InsP3Rs control different functional pools of Ca2+ stored in the SR we superfused ESdCs with ET-1 (100 nmol/L) after the caffeine sensitive stores were depleted (caffeine: 10 mmol/L; Fig. 3A). The refilling of the stores was prevented by caffeine in the extracellular Ca2+-free solution. After recovery from the caffeine induced Ca2+ release, ET-1 induced a small but significant increase in basal [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3BC). The ET-1 induced change indicates the presence of an InsP3R regulated SR Ca2+ pool in ESdCs that is independent of caffeine-sensitive stores. This is consistent with the fact that ESdCs maintain their spontaneous activity when RyR sensitive stores are depleted by caffeine [9].

Figure 3. InsP3R controlled Ca2+ stores are in part functionally separated from RYR controlled stores.

A: F/F0 plot of [Ca2+]i in a spontaneously active ESdC after superfusion of the cell with tyrode solution supplemented with 4 mmol/L Ca2+. After depletion of ryanodine receptor operated Ca2+ stores by 10 mmol/L caffeine, ET-1 (100 nmol/L) induced an increase in basal [Ca2+]i. B: Magnification of the section of the F/F0 plot indicated by the box. C: Bar graph illustrating the increase in basal Ca2+ induced by ET-1 in the presence of caffeine (n = 6; *: P<0.05).

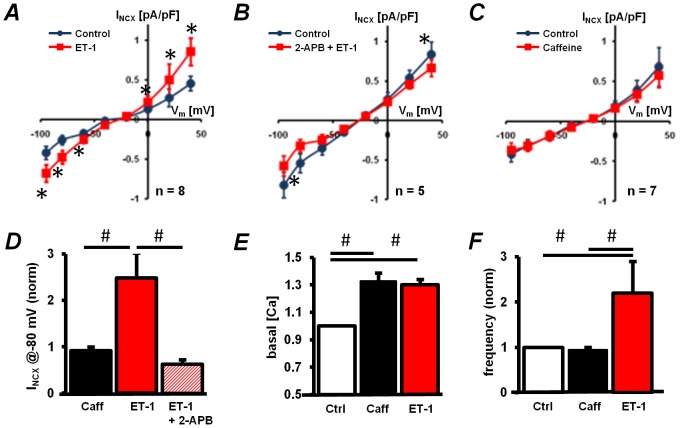

To determine if stimulation of InsP3Rs can influence NCX activity we measured INCX during the superfusion of ESdCs with ET-1 (100 nmol/L; for details on the voltage protocol see Data S1). A significant increase of INCX was determined in the presence of ET-1 (Fig. 4AD). This ET-1 induced increase, was inhibited by the InsP3R blocker 2-APB (2 µmol/L, Fig. 4BD). To determine whether the effect of ET-1 depended on an overall increase in basal [Ca2+]i we measured INCX in ESdCs superfused with 100 µmol/L caffeine. At this concentration caffeine increases the open probability of RyRs and leads to increased diastolic [Ca2+]i. Caffeine and ET-1 both increased basal [Ca2+]i to a similar extent (Fig. 4E). However, the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+-transients was only increased during ET-1 superfusion while it remained unchanged in the presence of caffeine (Fig. 4F). Consistent with this, INCX remained unchanged following 3 min of superfusion with caffeine (Fig. 4CD). These findings support that InsP3R dependent Ca2+ release more efficiently enhances INCX activity.

Figure 4. InsP3R induced Ca2+ release stimulates NCX activity.

Current voltage plots for INCX recorded in ESdCs under control conditions and after 3 min superfusion with either A: ET-1 (100 nmol/L; n = 8), B: ET-1 (100 nmol/L)+2-APB (2 µmol/L; n = 5), or C: caffeine (Caff: 100 µmol/L; n = 7). Currents are corrected for the nickel (5 mmol/L) insensitive background. D: Normalized INCX recorded at −80 mV. INCX recorded on superfusion with ET-1 was significantly different from Caff and ET-1+2-APB. E: Normalized change in basal [Ca2+]i. Significant increase of basal [Ca2+]i was observed upon superfusion with Caff and ET-1. F: ESdCs beating frequency after 3 min superfusion with ET-1 (n = 4) or caffeine (n = 6) respectively. *: paired t-test P<0.05; #: one way ANOVA P<0.05.

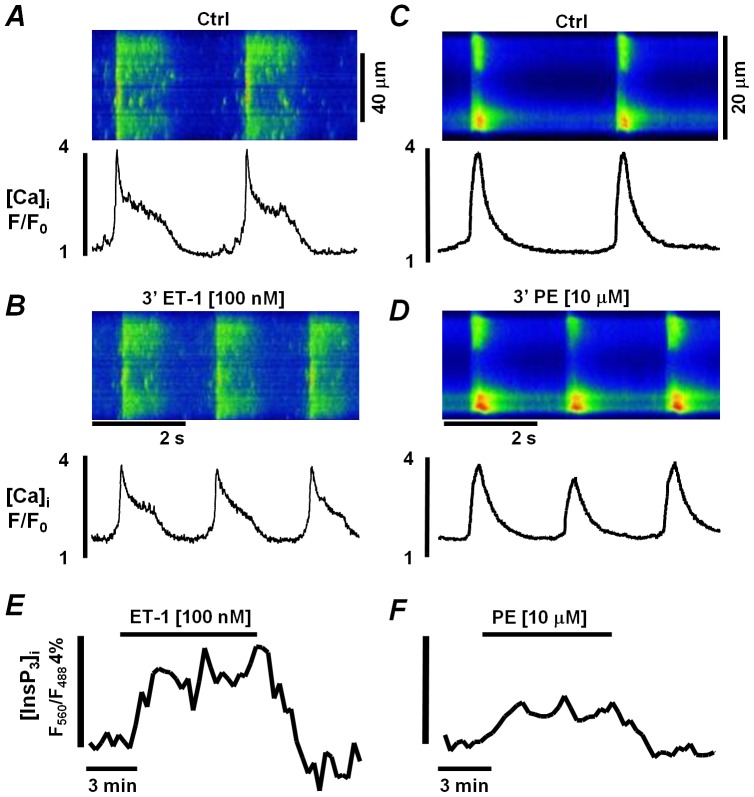

To determine the spatial organization of InsP3 signaling in ESdCs we transduced cells with an adenovirus expressing FIRE-1 (24 h). FIRE-1 exhibits an increase in the fluorescence ratio (F560/F480) upon binding of InsP3 [24]. When InsP3 production in ESdCs was stimulated by ET-1 (100 nmol/L) or PE (10 µmol/L) a positive chronotropic effect was determined in the frequency of the spontaneous Ca2+ transients (Fig. 5AB and CD, respectively) with a 3.0±1.1 fold (from 0.13±0.03 Hz to 0.32±0.06 Hz; n = 4) and a 1.5±0.3 (from 0.5±0.12 Hz to 0.65±0.1 Hz; n = 5) fold increase in the frequency after 3 minutes of superfusion, respectively. In FIRE-1 expressing ESdCs the same superfusion protocol was applied. When the fluorescence was integrated over the entire width of the cell, an ET-1 or PE induced increase in the FRET ratio (F560/F488) was determined that reached a steady state after about 2.5 min of superfusion. For ET-1, a 3.7±0.6% change (Fig. 5E & 6F; n = 4) in the FRET ratio was determined while the change for PE amounted to 1.7±0.03% (Fig. 5F & 6F; n = 2). The increase returned to baseline upon washout (Fig. 5E and F). When FIRE-1 infected ESdCs were superfused with the PLC inhibitor U73122 (1 µmol/L) a reversible decrease in F560/F488 (Fig. 6A; n = 5) was determined indicating a reduction in basal InsP3 production. U73343 (1 µmol/L) the inactive analog of U73122 remained without effect (Fig. 6B; n = 2). To exclude that changes in FRET ratio with U73122 were due to a decrease in basal [Ca2+]i we used 3 alternative approaches to reduce basal [Ca2+]i and spontaneous activity in ESdCs. During superfusion of ESdCs with either 2-APB (Fig. 6C), Ca2+-free solution (Fig. 6D) or BAPTA-AM (Fig. 6E) the florescent ratio F560/F488 was determined. We had previously demonstrated that these interventions attenuate ESdCs spontaneous activity and reduce basal [Ca2+]i by 18.1±6.9% (n = 2) and 18.6±0.36% (n = 2), and 27.05±1.5% (n = 3), respectively [9]. Under none of the conditions, (Ca2+-free, n = 3; 2-APB: 2 µmol/L, n = 3; or BAPTA/AM: 1 µmol/L, n = 2) was a change in the FRET ratio (F560/F488) measured indicating that changes in FIRE-1 did not depend on changes in [Ca2+]i or spontaneous activity.

Figure 5. Agonist induced InsP3 increase regulates ESdC beating frequency.

Line scan and corresponding F/F0 plots from spontaneously active ESdCs in Ctrl conditions (A, C) and after superfusion with either B: ET-1 (100 nmol/L) or D: PE (10 µmol/L). Superfusion of FIRE-1 expressing cells with E: ET-1 (n = 4) or F: PE (n = 2) induced an increase in the fluorescence ratio F560/F488 indicating an increase in [InsP3]i.

Figure 6. Changes in [IP3]i are independent of [Ca]i.

Fluorescence ratio F560/F488 measured in FIRE-1 expressing ESdCs superfused with A: the PLC inhibitor, U73122 (1 µmol/L; n = 5), B: its inactive analog, U73343 (1 µmol/L; n = 2), C: the InsP3R blocker, 2-APB (2 µmol/L; n = 2), D: Ca2+ -free solution (n = 2) or E: BAPTA-AM. F: The normalized changes of F560/F488 recorded in ET-1, PE or U73122. #: one way ANOVA P<0.05.

FIRE-1 transduction changed the spontaneous activity in ESdCs. The overall number of spontaneously active cells was reduced and in beating cells the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients was attenuated (FIRE-1: 0.43±0.09 Hz; n = 5) compared to non-transduced cells (Control: 0.93±0.1 Hz; n = 11) of the same age (day 16). The results indicate that the InsP3 buffer capacity of FIRE-1 in ESdCs reduces the beating frequency. To determine if frequency regulation through InsP3-mediated Ca2+-release depends on defined InsP3 signaling domains we employed two different strategies. First we limited peri-nuclear and nuclear InsP3 signaling by expression of FIRE-1 with a nuclear localization sequence (FIRE-1nuc), second we limited sub-sarcolemmal InsP3 signaling by over-expression of the membrane associated inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase m43 [29]. The enzyme m43 rapidly degrades InsP3 by removing the 5′ phosphate [25].

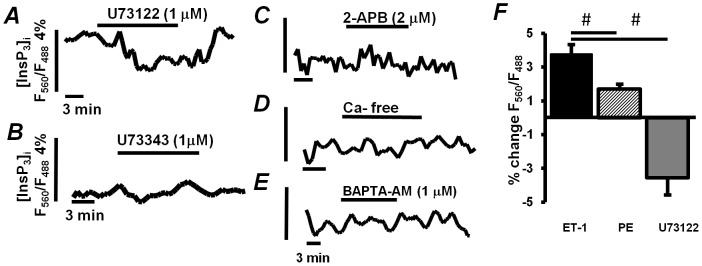

The spatially defined localization of both FIRE-1nuc and m43 was confirmed by adenoviral transduction of the two constructs in atrial and ventricular myocytes as well as ESdCs. FIRE-1nuc was readily identified by its YFP fluorescence and the m43-phosphatase was visualized with an antibody against the incorporated FLAG-tag. Figure 7 shows a cat ventricular myocyte (A) and an isolated ESdC (B) expressing FIRE-1nuc. The fluorescence profile (C) obtained along a line positioned through the ESdC demonstrates the predominant localization of FIRE-1nuc to the nuclear envelope. The sub-cellular localization of m43 was determined through immunoblotting of fractionated whole cell lysate from COS-1 cells expressing FLAG-tagged m43 (SFig. 2) and immunostaining of transduced cat atrial myocytes (Fig. 7D) and ESdCs (Fig. 7E). Immunoblotting clearly localizes m43 in the membrane fraction of the cell lysate and immunostainings show a preferential localization of m43 at the plasma membrane of atrial myocytes and ESdCs 24 hours post adenoviral transduction. The distribution is in agreement with previous findings of Vasilevski et al. (2008) [25].

Figure 7. Subcellular buffering of [InsP3] at the nucleus and the plasma membrane.

FIRE-1nuc infected A: ventricular myocytes and B: ESdCs exhibit pronounced YFP-fluorescence in the nucleus as demonstrated by the fluorescence plot (C) along the line shown in B. Immunostaining of m43 infected D: atrial myocyte and E: ESdCs with antibodies against FLAG tag. F: Fluorescence plot along the line shown in E demonstrates that m43 localizes predominantly to the plasma membrane.

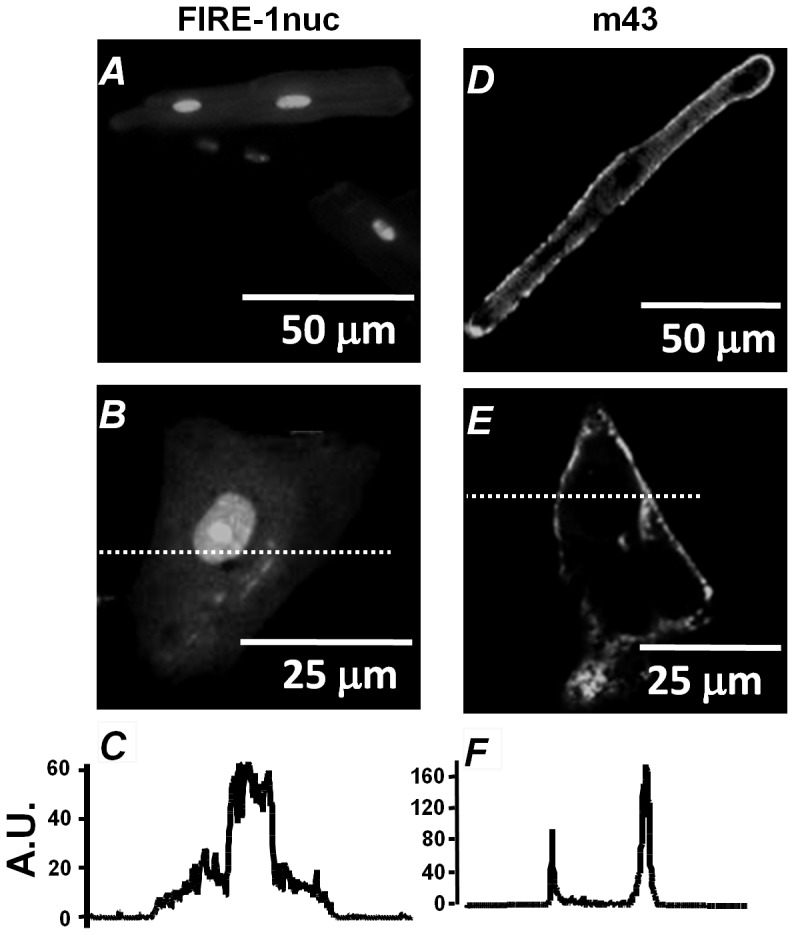

To determine how localized suppression of InsP3 signaling effects the spontaneous activity of ESdCs we measured [Ca2+]i in cells expressing m43 or FIRE-1nuc 24 hours post adenoviral transduction. Figure 8A shows spontaneous whole cell Ca2+ transients in an ESdC expressing FIRE-1nuc. Non-transduced 14 days old cells obtained from the same isolation served as control. Control ESdCs and ESdCs transduced with FIRE-1nuc exhibited no significant difference in their Ca2+ transient frequency (0.51±0.05 Hz; n = 7 and 0.44±0.02 Hz; n = 6, respectively; Fig. 8C). Upon stimulation with ET-1 the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients increased 58±9% (n = 3) in control and 24±1% (n = 4; P<0.05) in FIRE-1nuc transduced ESdCs. The data indicate that the ET-1 induced positive chronotropic effect persists when InsP3R is buffered in the nucleus of ESdCs. In contrast, cells transduced with m43 exhibited a significantly reduced beating frequency in comparison to control and FIRE-1nuc cells (54±9% of control; n = 5; P<0.05; Fig. 8BC) and an ET-1 induced positive chronotropic effect was not observed (Fig. 8C). The data support the hypothesis that membrane delineated inhibition of InsP3 signaling can efficiently modulate the spontaneous activity of ESdCs.

Figure 8. Pacemaker activity in ESdCs is regulated by sub-sarcolemmal Ca2+ release.

Line scan and F/F0 plot from A: FIRE-1nuc and B: m43 infected spontaneously active ESdCs. C: Normalized beating frequency of control (black, n = 7), FIRE-1nuc (grey, n = 6) and m43 (red, n = 5) infected ESdCs in ctrl and after superfusion with ET-1 (hatched; n = 3, n = 4, n = 5, respectively). (*: P<0.05 compared to endogenous Ctrl; #, &: P<0.05 compared to Ctrl or Ctrl+ET-1, respectively).

Discussion

In the present study we demonstrate that a basal production of InsP3 maintains spontaneous activity in ESdCs by regulating Ca2+-release from a SR Ca2+ pool that is functionally independent from RyR-mediated Ca2+-release. In addition we show that while InsP3 production changes [Ca2+]i throughout the cytoplasm, the InsP3R signaling domains relevant for NCX activation and spontaneous activity are localized close to the plasma membrane where their Ca2+ release is efficiently translated into a depolarization of the membrane potential.

InsP3Rs in developing cardiomyocytes

All three InsP3R subtypes -1, -2, and -3 are expressed in un-differentiated ES cells [30] and embryonic cardiomyocytes [1], [3], [31] where InsP3R1 is most prevalent in the nuclear envelope [3], [10]. We have identified InsP3R1 and InsP3R2 in ESdCs (see Fig. 2B,E) with a sub-cellular distribution comparable to that in neonatal myocytes [4]. Previous studies also suggested that InsP3R1 maintains spontaneous activity in embryonic cardiomyocytes which was suppressed with introduction of antisense cDNA of InsP3R1 [10].

Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum by InsP3Rs

The SR is a continuous network [32] where Ca2+ can redistribute [18], [33]–[35]. InsP3Rs and RyRs localize to and deplete the same SR network in rabbit ventricular myocytes [33]. Interestingly our data demonstrate that InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release can still be induced when RyR-controlled Ca2+ stores were depleted by caffeine. This supports the hypothesis that InsP3R signaling domains are functionally isolated and not immediately affected by RyR-controlled Ca2+ store depletion. A similar finding was described in colonic smooth muscle cells where in an interconnected SR network, Ca2+ release from RyR or InsP3R controlled stores could be demonstrated after depletion of the respective other InsP3 or caffeine sensitive store [36]. In ESdCs the size of this functionally independent InsP3 sensitive Ca2+ store remains to be determined but as demonstrated, it is sufficient to maintain spontaneous activity of ESdCs [9].

Role of InsP3Rs for the generation of spontaneous activity

We and others have demonstrated that Ca2+ release plays a dominant role in the generation of spontaneous Ca2+ transients in mouse [3], [7], [9], [10], [37] and human embryonic cardiomyocytes [11], [26]. The transients coincide with changes in Vm, and the late phase of the diastolic depolarization is accompanied by an increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1). A similar increase in [Ca2+]i was described in cat latent pacemaker cells and cat and rabbit sinus nodal cells [27], [38] where sub-sarcolemmal Ca2+ release from RyRs is proposed to enhance a depolarization of Vm by activation of NCX.

In latent pacemaker and sinus nodal cells the Ca2+ release events that drive the depolarization are localized in the sub-sarcolemmal space. However, in ESdCs it was proposed that the Ca2+ release that initiates the diastolic depolarization originates at the nuclear envelope [7], [8], . This was supported by the nuclear localization of InsP3Rs and the demonstration of peri-nuclear InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release [7], [8],[40]. While most of the InsP3 synthesis occurs at the plasma membrane PLCs and InsP3 production are also described within the nuclear envelope [41]. In our experiments nuclear InsP3 buffering through FIRE-1nuc had no significant effect on Ca2+ transient frequency thus excluding a major contribution of nuclear PLCs to spontaneous activity.

In cardiac myocytes, stimulation of InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release by ET-1 can induce spontaneous arrhythmic Ca2+ transients although RyRs outnumber InsP3Rs by 50∶1 [19], [20], [42]. Differences in InsP3R to RyR signaling are also reflected in our data where ET-1 but not caffeine has a positive chronotropic effect (Fig. 4F) in ESdCs. The efficient translation of InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release into a depolarization of Vm, could depend on the localization of InsP3R close to the plasma membrane or within a functional signaling domain. A close apposition was demonstrated in rat atrial myocytes [43], and proposed in rat ventricular myocytes [19]. Data from Harzheim et al. (2009) [20] show that in hypertrophic rat ventricular myocytes InsP3Rs predominantly increase in the cytoplasm and correlate with enhanced ET-1 induced arrhythmic activity. Our data demonstrate that over-expression of the InsP3 5-phosphatase m43 [25], [29] in the plasma-membrane [44] decreased ESdCs beating frequency and abolished ET-1 induced positive chronotropy (Fig. 8C). This is consistent with previous results from neonatal cardiomyocytes where m43 reduced the InsP3 response after α-adrenergic stimulation [25] and supports that the InsP3 production and the InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release relevant to spontaneous activity occurs at the plasma membrane.

In addition to a preferred sub-sarcolemmal location of InsP3Rs, the formation of a specialized signaling domain could explain the efficient translation of Ca2+ release into changes of Vm. Signaling domains between InsP3Rs and the effector proteins NCX or the Ca2+ activated chloride channel have been demonstrated. The adaptor protein ankyrin [45] that binds to NCX and InsP3R [46] could form a potential linker that maintains a close spatial and functional proximity between the proteins. Recent data show that decreased levels of ankyrin attenuate sinus node activity [47], [48]; so future experiments will have to reveal how ankyrin loss changes the functional coupling between InsP3R mediated Ca2+ release and INCX.

Conclusion

In the current study we demonstrate that spontaneous activity in ESdCs depends on sub-sarcolemmal signaling domains of InsP3R and NCX that allow an efficient translation of InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release into a depolarization of the plasma membrane. While the InsP3 signaling domain described around the nucleus of adult and neonatal ventricular myocytes might enable excitation-transcription coupling, sub-sarcolemmal InsP3 signaling has significant impact on cellular excitability and arrhythmicity. The data indicate that pathological changes in cardiac muscle cells might not only depend on the level of InsP3R expression but more critically on their location within the myocytes.

Supporting Information

Supporting information.

(DOC)

A. Fluorescent images of an ESdC taken at >560 nm (top) and 488 nm (bottom) before (left) and after bleaching (right). B. Bar graphs display the change in CFP (right) and decrease of YFP (right) fluorescence after photobleaching (hatched bar, n = 3). The results are comparable to bleaching experiments in FIRE-1 expressing COS-1 cells [12].

(TIF)

Western blot of the cytoplasmic (soluble) and membrane fraction (pellet) of M43 transfected COS cells. Blots probed with the anti-tag antibody show positive M43 immunostaining only in the membrane fraction.

(TIF)

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (HL89617 to KB; PO1HL080101 to GAM; HL062231 and HL080101 to LAB) and AHA (0330393Z to KB). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Rosemblit N, Moschella MC, Ondriasa E, Gutstein DE, Ondrias K, et al. (1999) Intracellular calcium release channel expression during embryogenesis. Dev Biol 206: 163–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Slavikova J, Dvorakova M, Reischig J, Palkovits M, Ondrias K, et al. (2006) IP3 type 1 receptors in the heart: their predominance in atrial walls with ganglion cells. Life Sci 78: 1598–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jaconi M, Bony C, Richards SM, Terzic A, Arnaudeau S, et al. (2000) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate directs Ca(2+) flow between mitochondria and the Endoplasmic/Sarcoplasmic reticulum: a role in regulating cardiac autonomic Ca(2+) spiking. Mol Biol Cell 11: 1845–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garcia KD, Shah T, Garcia J (2004) Immunolocalization of type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in cardiac myocytes from newborn mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1048–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luo D, Yang D, Lan X, Li K, Li X, et al. (2007) Nuclear Ca(2+) sparks and waves mediated by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cell Calcium [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Escobar M, Cardenas C, Colavita K, Petrenko NB, Franzini-Armstrong C (2011) Structural evidence for perinuclear calcium microdomains in cardiac myocytes. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 50: 451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sasse P, Zhang J, Cleemann L, Morad M, Hescheler J, et al. (2007) Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations, a potential pacemaking mechanism in early embryonic heart cells. J Gen Physiol 130: 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Janowski E, Cleemann L, Sasse P, Morad M (2006) Diversity of Ca2+ signaling in developing cardiac cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1080: 154–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kapur N, Banach K (2007) Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated spontaneous activity in mouse embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J Physiol 581: 1113–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mery A, Aimond F, Menard C, Mikoshiba K, Michalak M, et al. (2005) Initiation of embryonic cardiac pacemaker activity by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent calcium signaling. Mol Biol Cell 16: 2414–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Satin J, Itzhaki I, Rapoport S, Schroder EA, Izu L, et al. (2008) Calcium Handling in Human Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells 26: 1961–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Itzhaki I, Rapoport S, Huber I, Mizrahi I, Zwi-Dantsis L, et al. (2011) Calcium handling in human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS ONE 6: e18037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lipp P, Laine M, Tovey SC, Burrell KM, Berridge MJ, et al. (2000) Functional InsP3 receptors that may modulate excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Curr Biol 10: 939–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bare DJ, Kettlun CS, Liang M, Bers DM, Mignery GA (2005) Cardiac type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor: interaction and modulation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem 280: 15912–15920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zima AV, Blatter LA (2004) Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Ca(2+) signalling in cat atrial excitation-contraction coupling and arrhythmias. J Physiol 555: 607–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Domeier TL, Zima AV, Maxwell JT, Huke S, Mignery GA, et al. (2008) IP3 receptor-dependent Ca2+ release modulates excitation-contraction coupling in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mohler PJ, Schott JJ, Gramolini AO, Dilly KW, Guatimosim S, et al. (2003) Ankyrin-B mutation causes type 4 long-QT cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Nature 421: 634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu X, Zhang T, Bossuyt J, Li X, McKinsey TA, et al. (2006) Local InsP3-dependent perinuclear Ca2+ signaling in cardiac myocyte excitation-transcription coupling. J Clin Invest 116: 675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Proven A, Roderick HL, Conway SJ, Berridge MJ, Horton JK, et al. (2006) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate supports the arrhythmogenic action of endothelin-1 on ventricular cardiac myocytes. J Cell Sci 119: 3363–3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harzheim D, Movassagh M, Foo RS, Ritter O, Tashfeen A, et al. (2009) Increased InsP3Rs in the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum augment Ca2+ transients and arrhythmias associated with cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11406–11411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horn T, Ullrich ND, Egger M (2013) ‘Eventless’ InsP3-dependent SR-Ca2+ release affecting atrial Ca2+ sparks. The Journal of physiology 591: 2103–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang HT, Tweedie D, Wang S, Guia A, Vinogradova T, et al. (2002) The ryanodine receptor modulates the spontaneous beating rate of cardiomyocytes during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 9225–9230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Banach K, Halbach MD, Hu P, Hescheler J, Egert U (2003) Development of electrical activity in cardiac myocyte aggregates derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H2114–H2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Remus TP, Zima AV, Bossuyt J, Bare DJ, Martin JL, et al. (2006) Biosensors to measure inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate concentration in living cells with spatiotemporal resolution. J Biol Chem 281: 608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vasilevski O, Grubb DR, Filtz TM, Yang S, McLeod-Dryden TJ, et al. (2008) Ins(1,4,5)P(3) regulates phospholipase Cbeta1 expression in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rapila R, Korhonen T, Tavi P (2008) Excitation-contraction coupling of the mouse embryonic cardiomyocyte. J Gen Physiol 132: 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bogdanov KY, Vinogradova TM, Lakatta EG (2001) Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchanger: molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ Res 88: 1254–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sauer H, Theben T, Hescheler J, Lindner M, Brandt MC, et al. (2001) Characteristics of calcium sparks in cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H411–H421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Speed CJ, Little PJ, Hayman JA, Mitchell CA (1996) Underexpression of the 43 kDa inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase is associated with cellular transformation. Embo J 15: 4852–4861. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kapur N, Mignery GA, Banach K (2007) Cell cycle-dependent calcium oscillations in mouse embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C1510–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Puceat M, Jaconi M (2005) Ca(2+) signalling in cardiogenesis. Cell Calcium 38: 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Tijskens P (2005) The assembly of calcium release units in cardiac muscle. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1047: 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu X, Bers DM (2006) Sarcoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope are one highly interconnected Ca2+ store throughout cardiac myocyte. Circ Res 99: 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zima AV, Picht E, Bers DM, Blatter LA (2008) Termination of cardiac Ca2+ sparks: role of intra-SR [Ca2+], release flux, and intra-SR Ca2+ diffusion. Circ Res 103: e105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Swietach P, Spitzer KW, Vaughan-Jones RD (2008) Ca2+-mobility in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of ventricular myocytes is low. Biophys J 95: 1412–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McCarron JG, Olson ML (2008) A single luminally continuous sarcoplasmic reticulum with apparently separate Ca2+ stores in smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 283: 7206–7218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Fleischmann BK, Liu Q, Sauer H, Gryshchenko O, et al. (1999) Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations drive spontaneous contractions in cardiomyocytes during early development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 8259–8264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huser J, Blatter LA, Lipsius SL (2000) Intracellular Ca2+ release contributes to automaticity in cat atrial pacemaker cells. J Physiol 524 Pt 2: 415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zima AV, Bare DJ, Mignery GA, Blatter LA (2007) IP3-dependent nuclear Ca signaling in the heart. J Physiol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zima AV, Bare DJ, Mignery GA, Blatter LA (2007) IP3-dependent nuclear Ca2+ signalling in the mammalian heart. J Physiol 584: 601–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gomes DA, Leite MF, Bennett AM, Nathanson MH (2006) Calcium signaling in the nucleus. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 84: 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Perez PJ, Ramos-Franco J, Fill M, Mignery GA (1997) Identification and functional reconstitution of the type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor from ventricular cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 272: 23961–23969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mackenzie L, Bootman MD, Laine M, Berridge MJ, Thuring J, et al. (2002) The role of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in Ca(2+) signalling and the generation of arrhythmias in rat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 541: 395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. De Smedt F, Boom A, Pesesse X, Schiffmann SN, Erneux C (1996) Post-translational modification of human brain type I inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase by farnesylation. J Biol Chem 271: 10419–10424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mohler PJ, Davis JQ, Davis LH, Hoffman JA, Michaely P, et al. (2004) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor localization and stability in neonatal cardiomyocytes requires interaction with ankyrin-B. J Biol Chem 279: 12980–12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bennett V, Baines AJ (2001) Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol Rev 81: 1353–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Le Scouarnec S, Bhasin N, Vieyres C, Hund TJ, Cunha SR, et al. (2008) Dysfunction in ankyrin-B-dependent ion channel and transporter targeting causes human sinus node disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 15617–15622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hund TJ, Mohler PJ (2008) Ankyrin-based targeting pathway regulates human sinoatrial node automaticity. Channels 2: 404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

(DOC)

A. Fluorescent images of an ESdC taken at >560 nm (top) and 488 nm (bottom) before (left) and after bleaching (right). B. Bar graphs display the change in CFP (right) and decrease of YFP (right) fluorescence after photobleaching (hatched bar, n = 3). The results are comparable to bleaching experiments in FIRE-1 expressing COS-1 cells [12].

(TIF)

Western blot of the cytoplasmic (soluble) and membrane fraction (pellet) of M43 transfected COS cells. Blots probed with the anti-tag antibody show positive M43 immunostaining only in the membrane fraction.

(TIF)