Abstract

Criterion validity of a novel accelerometry device that measures caloric expenditure (Fitbit) was evaluated against a self-report estimation of caloric expenditure (CHAMPS questionnaire) in older adults. CHAMPS and Fitbit estimates of total caloric expenditure/day were significantly correlated (r=.61, p<.05). Bland-Altman plots indicated that 70% of participants’ data were within 1 standard deviation of the mean difference between measures. These preliminary findings suggest that the Fitbit may be considered a viable instrument for measuring daily caloric expenditure among older adults. However, further work is required to determine the optimal measurement technique for caloric expenditure among older adults.

The beneficial effect of physical activity on the health and wellbeing of older adults is well established. Physical activity reduces the likelihood of chronic diseases, increases functional health, promotes social engagement (Meisner, Dogra, Logan, Baker, & Weir, 2010; Stathi, McKenna, & Fox, 2010), and is associated with better psychological health (McHugh & Lawler, 2011). However, questions remain about the duration and intensity of physical activity needed to produce a desired effect (dose-response relationship) among older adults. Accordingly, valid measurement tools are necessary to accurately document physical activity levels among older adults, who tend to be less physically active and participate in lower-intensity activity

Physical activity measurement among older adults is often complicated because traditional self-report measures likely underestimate their physical activity (Harada, Chiu, King, & Stewart, 2001). Older adults typically engage in light activities at low energy expenditures, and tend to perform these activities on an irregular basis (Harada et al., 2001; Pruit et al., 2008). Furthermore, older adults may have difficulty with memory and cognition, which could inhibit their ability to recall past physical activity behaviors (Baranowski, 1988; Harada et al., 2001). However, the Community Health Activities Model Program for Seniors (CHAMPS) questionnaire was specifically developed for administration to older adults and uniquely calculates weekly kilocalorie expenditure (kcal) in exercise-related activities (Stewart et al., 1997; Stewart et al., 2001). The CHAMPS questionnaire has consistently demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity among older adults (Colbert et al., 2011; Giles & Marshall, 2009; Harada et al., 2001; Stewart et al., 1997, Stewart et al., 2001).

Among aging populations, objective devices (accelerometers) offer a valuable supplement to traditional self-report measures. While appealing to avoid recall bias, accelerometers also provide objective means of capturing body movement and measuring caloric expenditure. However, little is known about concordance between subjective and various objective devices of kcal expenditure among this population. To date, results have been encouraging for the validity of the ActiGraph accelerometer among older adults (Boon et al., 2003; Focht et al., 2003). However, as alternative accelerometry devices become widely available, it is important to evaluate their reliability and validity for use among older adult samples. Our objective was to examine criterion validity of a novel measurement device (Fitbit), by comparing the Fitbit-calculated kcal to subjective estimations of kcal (CHAMPS) among a sample of healthy, older adults.

Methods

Sample

Participants were ten adults who ranged in age from 60 – 68 years (M age = 63.8 years, SD = 3.17 years). Most participants were men, married, and employed in a University setting. All participants were white and had earned a college degree; eight completed additional graduate work. A majority were categorized as normal weight, as a mean body mass index (BMI) of 24.5 (SD=4.17) was obtained. On average, participants reported three (SD=1.58) chronic health conditions [arthritis (50%), sleeping problems (50%), and hypertension (40%) most commonly reported] and zero functional limitations (SD=0). On a scale of (1) very good to (6) very poor, participants rated their physical and mental health to be “good.”

Measures and Procedures

Participants were recruited via e-mail and word of mouth, and asked to volunteer to be part of a larger 10-day study examining older adults’ daily activity. Electronic recruitment flyers were distributed via an e-mail listserv to WVU faculty and staff. The study was approved by the institutional review board at West Virginia University (WVU). Written informed consent was obtained from all older adults. Sixteen older adults contacted the PI to participate. One older adult declined to participate due to time constraints. Of the remaining fifteen participants, 5 were dropped from the study because they experienced difficulty with the Fitbit and did not have objective data on which to compare their subjectively measured kcal. These difficulties included user errors, such as losing the Fitbit device (n =2), and failing to plug in a wireless base station that transmitted kcal data to the PI (n =3). The physical nature of the device (can be lost), and user interface (failure to charge it) are limitations to this objective measure, which disrupted data collection among 33% of the total sample. Participants received a $25 honorarium for study completion.

Subjectively measured total daily kcal

Participants completed the CHAMPS questionnaire, to report their typical weekly frequency and duration of 40 physical activities that are commonly reported by older adults (Stewart et al., 2001). Each activity is assigned a metabolic equivalent of task (MET) value that had been adjusted for older adult populations. The CHAMPS yields an estimated caloric expenditure/week in all exercise-related activities based on the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM, 2005) formula:(kcal/minute = METs * 3.5 * [body weight in kg/200]). The CHAMPS formula converts this into kcal/week, which we divided by seven (days) to obtain kcal/day.

Participants reported their age, sex, height, and weight, which were used to calculate their daily basal metabolic rate ([BMR] amount of calories expended at rest) according to the Harris Benedict (1918) Energy Equation. We added participants’ BMR to their CHAMPS kcal/day to obtain subjectively measured total kcal/day (CHAPMPS+BMR).

Objectively measured total daily kcal

Participant total kcal/day was objectively measured with the Fitbit (Fitbit, Inc., San Francisco, California)—a small accelerometer device worn on the waist. The Fitbit measures general body movements, and calculates BMR from participant specs: age, sex, height, and weight. Through a web-based interface, the Fitbit calculates total kcal/day based on each individual’s BMR and their general body movements (Fitbit, 2010). Fitbit uses 3D motion sensing technology and converts this into activity information including the intensity (light, moderate, vigorous) and duration of activities. Participant specs were entered into the Fitbit interface, and then participants wore the device during all waking hours for 10 consecutive days. Each participant’s daily kcal values were averaged across the 10-day study period to obtain a stable measure of objectively measured total kcal/day.

The Fitbit manufacturer’s website reports that “the Fitbit is very accurate and correlates well with other accelerometers”, and “Calorie data from the Tracker is very similar to those from energy expenditure measurement devices used in clinical research,” but no evidence is provided (Fitbit 2010). However, one study recently assessed the validity of the Fitbit to measure sleep (Montgomery-Downs, Insana, & Bond, 2011), and concluded that the Fitbit is an acceptable activity measurement device to infer sleep among normative populations.

Results

Baseline CHAMPS data indicated that participants were ‘very active’ (for comparison, see Stewart et al., 2001). Older adults self-reported engaging in 3.3 activities (SD=0.98) (of which 1.8 (SD=0.85) were moderate-intensity activities) on a daily basis. Common activities included light housework (80%), walking to do errands (60%), and walking leisurely for exercise or pleasure (60%). Common moderate-intensity activities included walking/hiking uphill (80%) and heavy strength training (50%). On average, older adults’ BMR was 1,545.97 (SD=272.66) kcal/day, and they self-reported expending 708.12 (SD=430.83) kcal/day in physical activities. Thus, averaged total daily caloric expenditure was 2,254.08 (SD=574.53) kcal/day. Averaged accelerometry-measured caloric expenditure was 2,059.10 (SD=315.35) kcal/day. Subjective and objective estimates of total kcal/day were significantly correlated (r=.61, p<.05).

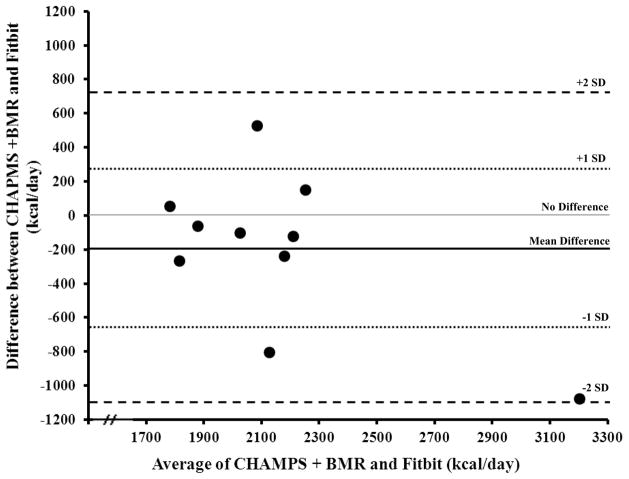

The Bland–Altman concordance technique (Altman & Bland, 1997) was used to compare the daily caloric expenditures estimated by the CHAMPS+BMR and Fitbit (Figure 1). Both CHAMPS and BMR formulas are established measures for use among older adults, whereas the Fitbit is not; therefore, comparison values were calculated in reference to the CHAMPS+BMR. Compared to the CHAMPS+BMR, the Fitbit underestimated kcal/day by an average of 194.99 (SD=±459.21) kcal. Approximately 70% of participants’ data were within one standard deviation (±458.28 kcal; range = -268.40 to 149.29) of the mean difference between measures, and 100% of participants’ data were within 2 standard deviations (±916.56 kcal; range = −1078.68 to 526.67). In reference to no difference between measures (i.e., y axis=0), the Fitbit underestimated kcal/day among 70% of participants and overestimated kcal/day among 30% of participants.

Figure 1. Concordance between caloric expenditure estimates from the CHAMPS+BSR and the Fitbit accelerometry-based activity monitoring device.

Notes: Mean Difference = −194.99 kcal; 1 SD = ± 458.28 kcal; 2 SD = ± 916.56 kcal. Standard Deviations are calculated based on mean difference. CHAMPS+BMR is the sum of the CHAMPS and the BMR measures. Abbreviations: CHAMPS, Community Health Activities Monitoring Program for Seniors; BMR, Basal Metabolic Rate; kcal, kilocalorie.

Discussion

Relative to the CHAMPS+BMR, the Fitbit underestimated kcal/day; yet, 70% of older adults’ data were within one standard deviation of the mean difference between measurement methods. Our results suggest that compared to the CHAMPS+BMR, the Fitbit may be an acceptable method to objectively measure kcal/day among older populations. These preliminary findings may assist other researchers considering the use of self-report or objective measurement methods for kcal/day expenditure among older adults. Depending on the research question and study goals, the Fitbit may be considered a viable instrument for measuring kcal/day among older adults. Still, future research is warranted in order to determine the optimal measurement technique for kcal/day among older adults. For instance, accelerometers are accepted as reliable instruments to estimate behaviors such as physical activity levels. However, some light activities that are common among older adults, such as slow walking, are less accurately measured (Prince et al., 2008). Therefore, we encourage replication of our study to examine the Fitbit validity for kcal/day assessment when compared to other objective measures (e.g., ActiGraph, SenseWear Pro3). Important for the measurement of activity among this population is the ability of a device to accurately capture activities of light intensity, because they are often poorly reported on questionnaires (Shephard, 2003). Accordingly, future research efforts could examine the ability of the Fitbit to accurately record kcal/day expenditure during light activities, as well as among heterogeneous samples of older adult populations. Given that 33% of data were lost due to user error, methods and procedures to improve user compliance are warranted (e.g., checklists, daily diaries).

Caloric expenditure measurement is one method to document physical activity among older adults. Objective devices that measure caloric expenditure could be used among older adults to set individual health goals, as well as among researchers to accurately measure physical activity. As technologies continue to develop and become more widely available, it is worthwhile to mention that objective measures of physical activity, including the Fitbit, offer benefits to researchers, clinicians, and the general public. As an easy-to-use and affordable method to quantify activity, the Fitbit (and similar devices) have strong appeal to both the general public and those working in health-related settings. For that reason, future research should include the Fitbit, and similar devices, in comparative validity studies of objective measures of caloric energy expenditure.

Our study had several limitations. The homogeneous sample size was small and selected from a University setting. Our study may not be replicable in a diverse sample of older adults. Unlike the CHAMPS, the Fitbit has not been designed for specific use among older adults; thus, suitability of the algorithm for use among particular populations is questionable. Fitbit does not permit access to their proprietary algorithm, which could theoretically be adjusted for use among specific populations such as older adults. Thirty percent of participants’ data were greater than 1SD above the mean difference. It is unclear what may account for this discrepancy between measures. It is possible that these participants experienced difficulty filling out the CHAMPS questionnaire and/or were unsuccessful in following study protocol and did not wear the Fitbit during all waking hours. Lastly, the 7-day CHAMPS+BMR measure and the 10-dayFitbit measurement were both used to infer kcal/day. Despite the differences in measurement timeframe, both measurement periods provided wide time samples to estimate a ‘typical’ kcal/day.

In summary, our study was an initial attempt to use a novel objective measurement device to measure kcal/day and to facilitate the evaluation of physical activity instruments among older adults. Future research should focus on validating objective measures of kcal/day for use among older adults, which can be guided by the findings identified in this preliminary report.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sydney Metheny and Tomorrow Wilson for their data collection, entry, and processing. We thank the older adults who participated in this study.

Funding source

This work was supported by a Graduate Research Grant (2009) from the Center for Excellence in Disabilities at West Virginia University.

References

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Measurement in medicine: The analysis of method comparison studies. Statistician. 1997;32:307–317. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 5. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T. Validity and reliability of self-report of physical activity: An information processing perspective. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 1988;59:314–327. [Google Scholar]

- Boon H, Frisard M, Brown C, et al. Validation of accelerometers to assess physical activity in elderly subjects. Obesity Research. 2003;11:A8. [Google Scholar]

- Colbert LH, Matthews CE, Havighurst TC, Kim K, Schoeller DA. Comparative validity of physical activity measures in older adults. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise. 2011;43(5):867–876. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181fc7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitbit. [accessed 29 October 2010];Fitbit FAQ. 2010 Available at: http://www.fitbit.com/faq#howaccurate.

- Focht BC, Sanders WM, Brubaker P, et al. Initial validation of the CSA activity monitor during rehabilitative exercise among older adults with chronic disease. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2003;11:293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Giles K, Marshall AL. Repeatability and accuracy of CHAMPS as a measure of physical activity in a community sample of older Australian adults. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2009;6(2):221–229. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada ND, Chiu V, King AC, Stewart AL. An evaluation of three self-report physical activity instruments for older adults. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise. 2001;33(6):962–70. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Benedict F. A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1918;4:370–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.4.12.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh JE, Lawlor BA. Exercise and social support are associated with psychological distress outcomes in a population of community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17:833–844. doi: 10.1177/1359105311423861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisner BA, Dogra S, Logan AJ, Baker J, Weir PL. Do or decline?: Comparing the effects of physical inactivity on biopsychosocial components of successful aging. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15:688–696. doi: 10.1177/1359105310368184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery-Downs HE, Insana SP, Bond JA. Movement toward a novel activity monitoring device. Sleep and Breathing. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11325-011-0585-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008;5:56–80. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruit LA, Glynn NW, King AC, et al. Use of accelerometry to measure physical activity in older adults at risk for mobility disability. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2008;16:416–434. doi: 10.1123/japa.16.4.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard R. Limits to the measurement of habitual physical activity by questionnaires. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2003;37(3):197–206. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathi A, Mckenna J, Fox KR. Processes associated with participation and adherence to a 12-month exercise programme for adults age 70 and older. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15:838–847. doi: 10.1177/1359105309357090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS Physical activity questionnaire for older adults: Outcomes and interventions. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise. 2001;33(7):1126–1141. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Mills KM, Sepsis PG, et al. Evaluation of CHAMPS, a physical activity promotion program for older adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;19(4):353–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02895154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]