Abstract

Objective

To determine whether random plasma glucose (RPG) collected from patients without known impaired glucose metabolism (IGM) in the emergency department (ED) is a useful screen for diabetes or prediabetes.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

ED of a Canadian teaching hospital over 1 month.

Participants

Adult patients in ED with RPG over 7 mmol/L were recruited for participation. Exclusion criteria included known diabetes, hospital admission and inability to consent. Participants were contacted by mail, encouraged to follow-up with their family physician (FP) for further testing and subsequently interviewed.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients in the ED with RPG over 7 mmol/L and no previous diagnosis of IGM who were diagnosed with diabetes or prediabetes after secondary testing by FP with oral glucose tolerance test or fasting plasma glucose (FPG). Secondary outcomes included patient characteristics (age, gender, body mass index and language) and (2) compliance with advice to seek an appropriate follow-up care.

Results

RPG was drawn on approximately one-third (33%, n=1149) of the 3470 patients in the ED in March 2010. RPG over 7 mmol/L was detected in 24% (n=278) of patients, and after first telephone follow-up, 32% (n=88/278) met the inclusion criteria and were advised to seek confirmatory testing. 41% (n=114/278) of patients were excluded for known diabetes. 73% of patients contacted (n=64/88) followed up with their FP. 12.5% (n=11/88) of patients had abnormal FPG, and of these 11% (n=10/88) were encouraged to initiate lifestyle modifications and 1% (n=1/88) was started on an oral hypoglycaemic agent. For 7% (n=6/88) of patients, FP's declined to do follow-up fasting blood work.

Conclusions

Elevated RPG in the ED is useful for identification of patients at risk for IGM and in need of further diabetic screening. Emergency physicians should advise patients with elevated RPG to consider screening for diabetes. For ED screening to be successful, patient education and collaboration with FPs are essential.

Keywords: Accident & Emergency Medicine, Preventive Medicine, Primary Care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A small sample size may have precluded determination of significant differences between subgroups.

Logistics of the study and health privacy concerns precluded collection of follow-up test results (ie, glycated haemoglobin, fasting plasma glucose and oral glucose tolerance tests) directly from the family physicians as opposed to that from participants of the study.

As the study was performed at a single site, generalisation to the Canadian urban emergency department population should be viewed cautiously.

Introduction

Approximately 300 million adults are affected with diabetes worldwide, and this number is expected to rise to 439 million over the next two decades.1 In Canada, an estimated 2.8 million people have been diagnosed with diabetes2 and approximately 6% of the population may be living with undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes.3 Diabetes is a cause of significant morbidity and mortality; it is a major contributor to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, and is the leading cause of blindness, end-stage renal failure and non-traumatic amputations in Canadians.4 In 2010, the estimated cost of diabetes to the Canadian economy was $6.3 billion annually, and this is expected to nearly triple over the next decade.5

Approximately 90% of diabetes in the population is type 2 diabetes (T2DM),6 which has a prolonged asymptomatic period of 5–12 years.7 During this time, hyperglycaemia develops insidiously and causes significant functional changes to various target tissues.7 8 At the time of diagnosis, about 20–30% have developed diabetes-related complications.8 Screening tests for diabetes allow diagnosis during the asymptomatic diabetic and prediabetic stages, and can contribute to reduced morbidity and mortality. The implementation of lifestyle and pharmacological interventions during the prediabetic stage can prolong and even prevent the onset of diabetes,9 10 and control of hyperglycaemia during the early diabetic stage has long-term benefits in delaying the progression of complications and reducing the risk of premature death.11

The diagnosis of diabetes is typically made on the basis of a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) >7 mmol/L, or random plasma glucose (RPG) >11.1 mmol/L with symptoms of diabetes or a 2 h plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L in a 75 G oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The term ‘prediabetes’ is a term for impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance, with conditions that place the patient at high risk of developing diabetes. Prediabetes is diagnosed on the basis of an FPG between 6.1 and 6.9 mmol/L, and warrants further confirmatory testing.4

Screening initiatives for diabetes have generally focused on the primary care setting and the use of FPG and OGTTs.12 Recently, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) has been accepted as an alternative diagnostic test for T2DM. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care advises HbA1c testing every 3–5 years for routine screening of adults at high risk of diabetes.13 However, an estimated 15.3% of the Canadian population does not have a family physician (FP) and these patients as well as those who do not visit their FP routinely are being missed by the current screening practices.14

Several studies have characterised the emergency department (ED) as a promising venue for diabetes screening, particularly of benefit for those individuals who do not have access to routine primary care. It is estimated that half of all patients in ED have an RPG drawn and there is emerging support of RPG as an opportunistic screening tool in the ED. RPG has a moderate correlation with HbA1c, and has been used to identify a significant portion of patients in EDs with undiagnosed impaired glucose metabolism (IGM).15–19

There have been no studies that have looked at RPG screening for diabetes in Canadian EDs. The primary objective of this study was to determine whether RPG collected in a Canadian ED is a useful way to screen for patients at risk for IGM who may otherwise not be identified. There are currently no guidelines for using RPG as a screening tool. In this study, a screening threshold of RPG >7 mmol/L was selected to minimise false positives yet provide adequate sensitivity to detect a large proportion of the patients who would warrant further confirmatory testing for prediabetes and diabetes. This glucose level was based on studies including that Ziemer et al19 explored the sensitivity and specificity of various RPG cut-offs and found that a cut-off of 7 mmol/L provided 93% specificity and 40% sensitivity for identifying diabetes.

Methods

Study design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

ED in Toronto Western Hospital (TWH), an urban teaching hospital in downtown Toronto that sees more than 40 000 emergency visits annually.

Participants

Using electronic chart review, we retrospectively identified patients visiting the ED over a 1-month period who had a RPG drawn in the ED. Patients of 18 years of age and older with RPG >7 mmol/L, with an access to telephone services, and who were able to provide verbal consent and were willing to complete follow-up testing (see below) were included in the study. Patients were excluded from the study if they: (1) had known IGM or a prior history of diabetes, (2) were on diabetic medication, (3) were admitted to hospital, (4) were deceased or (5) were unable to provide informed consent as they were non-English speakers or confused.

Methods

The hospital electronic patient record data were searched retrospectively for ED visits during a 1-month period in cases where RPG was sampled and was >7 mmol/L. Flagged charts were reviewed by the researcher (BB) to identify inclusion/exclusion criteria and for recording of additional demographic information (ie, age, gender and language). A letter of introduction to the study (with opt-out option) was mailed to patients meeting inclusion criteria. The letter also included the level of the patient's elevated RPG, with instructions to follow-up with their family doctor for further diabetic screening. Within 2–4 weeks of posting the letter these patients were contacted by telephone by one of the researchers (Janaki Vallipuram, Brenda Baswick and Andrea Scott). If the patient provided verbal consent, a brief standardised telephone interview was conducted, and the patient was advised to seek confirmatory testing with a primary care provider. A second postintervention phone follow-up was made to determine whether the patient sought a follow-up care, and to record the results of follow-up tests. In order to maximise data acquisition, a minimum of eight attempts over 8 weeks were undertaken for participants who were difficult to reach or who delayed seeking follow-up care.

This study was powered to identify at least 10 patients with diabetes with incidental findings of elevated RPG. On the basis of previously reported studies, we anticipated a 20% prevalence of new diagnosis of diabetes. With worst case scenario expectations of 50% of charts with RPG>7 mmol/L meeting the exclusion criteria, 50% compliance with first telephone interview and 80% participation in second telephone interview, we aimed to analyse at least 250 ED visits with RPG >7 mmol/L.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients in ED with RPG (over 7 mmol/L) and no previous diagnosis of IGM who were diagnosed with diabetes or prediabetes as determined by secondary testing by FPs with the OGTT or FPG. The secondary outcomes were: (1) characteristics (by age, gender, body mass index (BMI) and language) of the patient population presenting with elevated RPG and (2) patient compliance when this population was encouraged to seek an appropriate follow-up care.

Data analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and transferred to SPSS V.17.0 for statistical analysis. Independent t tests were used to compare means for continuous variables, and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

Results

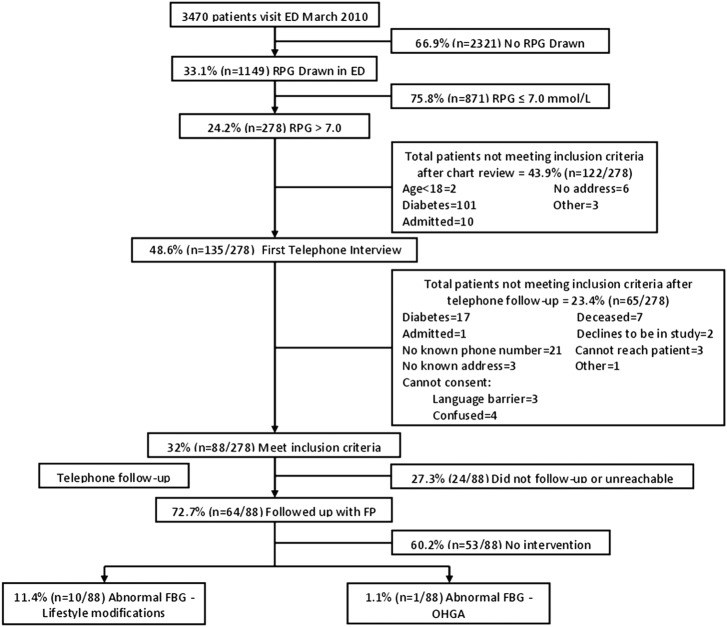

During the 1-month study period (March 2010), 3470 patients visited the TWH ED. Thirty-three per cent (n=1149) of these patients had RPG measured and of these patients 24% (n=278) had an RPG over 7 mmol/L. After the first telephone follow-up, 31% (n=88/278) of the patients met the inclusion criteria to participate in the study (see figure 1 for flow diagram of participants).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram. ED, emergency department; FBG, fasting blood glucose; FP, family physician; OHGA, oral hypoglycaemic agent; RPG, random plasma glucose.

The mean RPG of enrolled participants was approximately 8.4 mmol/L and BMI was approximately 28 kg/m2. Patients who were not contactable did not significantly differ by age or gender from those who were reached for telephone interview. (data not shown). The majority of these patients spoke English (77%, n = 68), followed by Portuguese (10%, n=9) and the others (13%, n=11) spoke 1 of 14 different languages (see table 1—baseline characteristics).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants included in final data analysis

| Age, BMI and RPG by gender |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n=39) | Male (n=49) | Range | |

| Age (years)† | 59.03±19.40 | 61.71±16.99 | 21–92 |

| BMI (kg/m2)† | 27.56±6.22 | 27.98±6.01 | 17.75–58.00 |

| RPG (mmol/L)† | 8.40±2.46 | 8.37±1.19 | 7.10–21.00 |

†Plus–minus values are means±SD.

‡n=9 of BMI missing data secondary to patients unable to provide weight and/or height.

BMI, body mass index; RPG, random plasma glucose.

Seventy-three per cent of patients (n=64) followed up with their FP. There were no significant differences in age, BMI or initial RPG between those who sought follow-up and those who did not. After 8 weeks and up to eight telephone attempts, 27.3% (24/88) were either unreachable or had not followed up with their family doctor.

Seventy-three per cent of patients (n=64/88) who participated in the telephone follow-up met their FP for blood-work. The FP subsequently diagnosed IGM in 12.5% (n=11/88 study participants meeting the inclusion criteria or 17.1% (11/64) of those following up with the FP), with institution of dietary and lifestyle modifications in 11.4% (n=10/88) and oral hypoglycaemic agent in 1.1% (n=1/88). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics (age, BMI and RPG) between those who were diagnosed with IGM versus those who were not (see table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients diagnosed with IGM versus not diagnosed

| Age, BMI and RPG in patients diagnosed with IGM vs patients not diagnosed with IGM | ||

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed with IGM (n=11) | Not diagnosed with IGM (n=53) | |

| Age (years)* | 66.73±12.59 | 59.48±18.10 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 27.45±4.17 | 24.73±9.85 |

| RPG (mmol/L)* | 8.61±1.03 | 8.42±2.05 |

*Plus–minus values are means±SD.

†n=24/88 of missing data secondary to patients not reachable or did not follow-up with FP after 8 weeks.

BMI, body mass index; FP, family physician; IGM, impaired glucose metabolism; RPG, random plasma glucose.

The FP did not perform confirmatory testing (ie, 75 G OGTT) in 7% (n=6/88) of patients who brought them the letter mailed from the ED advising confirmatory testing.

Discussion

Approximately one in eight people without previously diagnosed diabetes who completed a follow-up were found to have IGM. RPG as a screening tool for diabetes in the acute care setting has been criticised on the grounds that transient stress-induced hyperglycaemia and the non-fasting state act as confounders that make the interpretation of this test difficult. Despite this, many studies have shown that when using an appropriate cut-off, RPG can reliably detect a significant portion of undiagnosed diabetes with acceptable specificity.15–20 George et al20 found that over half of patients presenting to the ED with undiagnosed diabetes and random capillary blood glucose over 7 mmol/L fulfilled criteria for IGM. This substantial number may be an underestimate as the researchers used only FPG and not the OGTT test for diagnosing IGM, thus missing people with impaired glucose tolerance. Charfen et al1,5 also found that among ED visitors with undiagnosed diabetes, 66% of those with two or more diabetes risk factors or RPG over 7 mmol/L (or over 7.8 mmol/L if food was ingested within 2 h of the test) fulfilled criteria for IGM. Ziemer et al19 analysed the sensitivity and specificity of various RPG cut-offs and found that a cut-off of 7 mmol/L has 93% specificity and 40% sensitivity for identifying diabetes.

A finding of IGM in one in eight people with previously undiagnosed diabetes is significant given the substantial burden that diabetes has at the individual and community levels. This screening effort did present some cost to patients and the healthcare system, including use of resources, clinician time and potential psychological stress in patients. One consideration to optimise cost versus benefit is to improve the yield of screening by targeting patients with risk factors for T2DM and/or those who do not regularly access primary care.

Age and BMI are important risk factors for diabetes.3 15 16 In our study, there was a non-significant trend towards a slightly higher age and BMI for people with impaired glucose tolerance, which is in keeping with findings from other studies. The lack of significant difference in our study may reflect a study sample size limitation.

A challenge in using the ED to screen for diabetes is the need for follow-up by patients with their FPs. A lack of follow-up has consistently been identified as a problem in other studies, often trending towards half of patients not following up.15 17 18 The high follow-up rate in our study may be attributable to a more health-conscious Canadian population or may likely be due to a substantial number of reminder telephone calls (minimum of 8) from the study researchers to patients delaying follow-up. Poor follow-up has often been cited as an argument against using the ED for routine screening.15 17 18 Suggestions for improvement include investigators notifying the FPs directly, ED diabetic teaching and reminders to patients to seek follow-up care.

A further challenge in using the ED for screening is a poor follow-up by physicians. In the current study, 7% of FPs did not conduct further testing despite the patient's request. In a pilot study by Hewat et al,18 the proportion was 50%. This phenomenon may be attributable to the controversial role for RPG in screening for diabetes and this stresses the importance of FP education to ensure an improved collaboration with the ED. A study by Ginde et al21 showed that in a US ED setting, elevated RPG was often overlooked and not communicated to patients by ED physicians. This supports the argument that ED physician education would also be an essential component of an ED diabetes screening programme.

Limitations

A small sample size may have precluded determination of significant differences between groups. As the study was performed at a single site, generalisation to the Canadian urban ED population should be viewed cautiously. For example, regional variations in practices and guidelines for ordering blood tests in the ED, reasons for patient presentation to the ED and premorbid health status (ie, prevalence of obesity diabetic risk factors) will impact generalisability of these results. However, similar studies from other parts of the world support these findings and suggest that a finding of high RPG should prompt further outpatient evaluation for diabetes.

Logistics of the study and health privacy concerns precluded collection of follow-up test results (ie, HbA1c, FPG and OGTT) directly from the FPs as opposed to from study participants. It would also have been informative to analyse presenting symptoms to the ED and time of last meal to determine other contributors to increased RPG. (We note that a proportion of RPG samples collected may have in fact been fasting for 8 h at the time that blood was drawn in the ED, and thus in fact serve as an FPG.) Analysis of diabetic risk factors and patient affiliation with a primary care providor both before and after the ED visit would have been beneficial. It is possible that patients who did not follow-up with their FP are a selected subgroup with different risk factors and disease prevalence from those who followed up.

While excluding patients who were admitted to the ED likely removed the majority of the more acutely ill patients with febrile illnesses, we felt that it would be worthwhile to include patients despite elevated temperature and the potential for more false positive random blood glucose results.

Conclusions

This was the first study looking at the use of the Canadian ED as a screening point for diabetes. This pilot study suggests that the ED has good potential to screen for T2DM, and supports the use of RPG as an opportunistic screening tool. For ED screening to be effective, good collaboration with FPs is essential. Further multicentred large-scale studies are required to form a more conclusive opinion with regard to the widespread use of Canadian EDs as a screening point.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SMF designed the trial and implemented the plan. BB and JV performed chart review and telephone interview. SMF and BB analysed the data. SMF, BB and JV drafted the manuscript. SMF revised the draft paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: University Health Network—(University of Toronto Teaching Hospital)—Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data published in this study will be made freely available on request, free of charge, in the format of an Excel spreadsheet, stripped of patient identifiers.

Prior Publication: This study was published in Can J Emerg Med in Abstract form: Baswick B, Scott A, Vallipuram J et al. Incidental findings of elevated random plasma glucose in the ED as a prompt for outpatient diabetes screening [abstract]. Can J Emerg Med, 2011;13:PP204–5.

References

- 1.Canadian Diabetes Association The prevalence and costs of diabetes [online]. 2012. [cited 1 Sep 2012]. http://www.diabetes.ca/documents/about diabetes/PrevalanceandCost_09.pdf

- 2.Report from the National Diabetes Surveillance System Diabetes in Canada [online]. 2008. [cited 1 Sep 2012]. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2009/ndssdic-snsddac-09/pdf/report-2009-eng.pdf

- 3.Leiter LA, Barr A, Belanger A, et al. Diabetes screening in Canada (DIASCAN) Study: prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and glucose intolerance in family physician offices. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1038–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada Canadian diabetes association 2008 clinical practice guidelines expert committee. Can J Diabetes 2008;32(Suppl 1):S1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Diabetes Association The cost of diabetes in Canada: the economic tsunami [online]. December 2009. [cited 1 Sep 2012]. http://www.diabetes.ca/docments/for-professionals/CJD--March_2010--Beatty.pdf

- 6.Centers for Disease Control National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011. 2011. [cited 1 Sep 2012]. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf

- 7.Harris MI, Klein R, Welborn TA, et al. Onset of NIDDM occurs at least 4–7 yr before clinical diagnosis. Diabetes Care 1992;15:815–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DECODE study group, European Diabetes Epidemiology Group Glucose tolerance and mortality: comparison of WHO and American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria. Diabetes epidemiology: collaborative analysis of diagnostic criteria in Europe. Lancet 1999;354:617–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeFronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani M. Type 2 diabetes can be prevented with early pharmacological intervention. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl 2):S202–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberopoulos EN, Tsouli S, Mikhailidis DP, et al. Preventing type 2 diabetes in high risk patients: an overview of lifestyle and pharmacological measures. Curr Drug Targets 2006;7: 211–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, et al. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1577–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backholer K, Chen L, Shaw J. Screening for diabetes. Pathology 2012;44:110–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care Recommendations on screening for type 2 diabetes in adults. CMAJ 2012;184:1687–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Canada Access to a regular medical doctor, 2011. 2011. [cited 1Sept 2012]. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-625-x/2012001/article/11656-eng.htm

- 15.Charfen MA, Ipp E, Kaji AH, et al. Detection of undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetic states in high risk emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:394–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverman RA, Pahk R, Carbone M, et al. The relationship of plasma glucose and HbA1c levels among emergency department patients with no prior history of diabetes mellitus. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:722–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginde AA, Enrico Cagliero MPH, Nathan DM, et al. Point of care glucose and haemoglobin A1c in emergency department patients without known diabetes: implications for opportunistic screening. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:1241–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewat N, McD Taylor D, Macdonald E. Pilot study of random finger prick glucose testing as a screening tool for type 2 diabetes mellitus in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2009;26:732–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziemer DC, Kolm P, Foster JK, et al. Random plasma glucose in serendipitous screening for glucose intolerance: screening for impaired glucose tolerance study 2. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:528–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George PM, Valabhji J, Dawood M, et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes in the accident and emergency department. Diabet Med 2005;22:1766–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginde AA, Savaser DJ, Camargo CA., Jr Limited communication and management of emergency department hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med 2009;4:45–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.