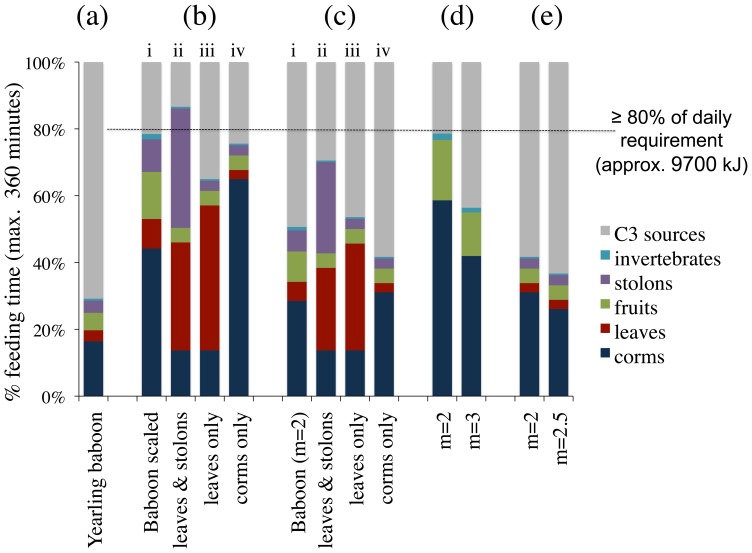

Figure 4. Summary diagram of the composition of diet eaten by a 34–49 kg hominin.

In (a) the empirical data for yearling Papio cynocephalus are shown. In (b) the basic model shown in (a) is scaled up to account for larger body masses and feeding on all C4 sources is increased until the target of approximately 9700 kJ is reached (i). Then, once the model has been scaled to larger body masses, only the time feeding for stolons, leaves, meristem and seeds is increased (ii.), or on leaves (iii) or corms (iv); feeding time on fruits and invertebrates was kept constant to the level of yearling baboons (ii–iv). In (c) the models outlined in (b) are repeated with improved manipulations skills for the processing of corms (m = 2). In (d) only C4 food sources that are well-suited to be broken down by P. boisei dento-cranial morphology, i.e. hard, brittle or soft, are selected. The effects of manipulatory capabilities (m) were tested. The models shown in (e) are considered most appropriate for inferences about the feeding ecology of P. boisei. These are achieved when all C4 sources are selected, but only feeding time on corms is increased beyond the time observed in yearling baboons. The total time available for feeding, including foraging, is assumed to be 50% of the day in all models, i.e. 360 minutes.