Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Their etiologies are unknown, but they are characterised by an imbalanced production of pro-inflammatory mediators, e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, as well as increased recruitment of leukocytes to the site of inflammation. Advantages in understanding the role of the inflammatory pathways in IBD and an inadequate response to conventional therapy in a large portion of patients, has over the last two decades lead to new therapies which includes the TNF inhibitors (TNFi), designed to target and neutralise the effect of TNF-α. TNFi have shown to be efficient in treating moderate to severe CD and UC. However, convenient alternative therapeutics targeting other immune pathways are needed for patients with IBD refractory to conventional therapy including TNFi. Indeed, several therapeutics are currently under development, and have shown success in clinical trials. These include antibodies targeting and neutralising interleukin-12/23, small pharmacologic Janus kinase inhibitors designed to block intracellular signaling of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, antibodies targeting integrins, and small anti-adhesion molecules that block adhesion between leukocytes and the intestinal vascular endothelium, reducing their infiltration into the inflamed mucosa. In this review we have elucidated the major signaling pathways of clinical importance for IBD therapy and highlighted the new promising therapies available. As stated in this paper several new treatment options are under development for the treatment of CD and UC, however, no drug fits all patients. Hence, optimisations of treatment regimens are warranted for the benefit of the patients either through biomarker establishment or other rationales to maximise the effect of the broad range of mode-of-actions of the present and future drugs in IBD.

Keywords: Anti-tumor necrosis factor, Biologics, Crohn’s disease, Pro-inflammatory cytokines, Signaling pathways, Treatment, Ulcerative colitis

Core tip: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are the two prevailing forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Both diseases are associated with an increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and immune cell infiltration of the inflamed tissue. Current treatment options with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors are discussed. Additionally, new therapeutic strategies showing promising results, e.g., small pharmacologic inhibitors aimed at inhibiting Janus kinase pathway and antibodies blocking recruitment of immune cells to the site of inflammation are also discussed. In this review we have elucidated the major signaling pathways of clinical importance for new therapeutic strategies of IBD.

INTRODUCTION

The intestine is an important part of the immune system that recognises and reacts to environmental stimuli, including its luminal microbes. This interaction is highly regulated and allows commensal bacteria of the normal microbiome to exist without induction of mucosal inflammation, a mechanism known as intestinal homeostasis[1]. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is generally hypothesised to be a multifactorial condition where a combination of luminal, environmental, and genetic factors triggers an inappropriate mucosal immune response. As a consequence, an inappropriate and continuing inflammatory response to commensal microbes results in the spontaneous release of pro-inflammatory cytokines which challenge the mucosal homeostasis[1]. These changes are to a some degree genetically determined and might lead to a dysfunction of the barrier integrity [mainly in ulcerative colitis (UC)], dysfunction in the sensing of microbes [mainly in Crohn’s disease (CD)], and changes in the regulation of adaptive immune responses (in both UC and CD)[2]. In IBD, this immune response does, however, not resolve, and the production of destructive inflammatory mediators continues. Inflammation in IBD is regulated by an increased secretion of a variety of pro-inflammatory mediators[3], and it is noteworthy that concentrations of cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α are elevated in the blood[4], intestinal mucosa[5,6] and stools[7] of patients with IBD. In addition to TNF-α, the increased secretion of a variety of other pro-inflammatory mediators in stools and rectal dialysates from patients with IBD have been observed as well[8-10].

An increased understanding of the involvement of inflammatory pathways combined with a lack of adequate response to conventional medical treatment has allowed biologics to emerge as an important modality in the treatment of patients with IBD. Several TNF inhibitors (TNFi) and other biologics as well as small molecules directed against pathways involving cytokines, adhesion molecules or other mediator systems involved in the pathogenesis of IBD have been developed and tested in clinical trials[3,11]. The aim of this review is from the present point of view to provide an overview of the pathways of inflammation which seems to be crucial for the management of IBD. Furthermore, a brief update on the latest clinical reports is given and promising new therapeutics are discussed.

REVIEW CRITERIA

The PubMed database was searched up to October 2013 using the following search terms: “TNF”, “anti-TNF”, “janus kinase”, “Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT)”, “tofacitinib”, “ustekinumab”, “IL-12/23”, “natalizumab”, “vedolizumab”, “vercirnon”, “integrins”, “chemokines”, “GSK-1605786A” individually or in combination with “IBD”, “Crohn’s disease”, “ulcerative colitis”, “inhibitors”, “therapies”, and “treatment”. The search focused predominantly on full-text papers published in the English-language. Abstracts were included when critically relevant and when not already available as full-text articles. No publication date restrictions were applied. Subsequently, articles were selected for inclusion in this review on the basis of their relevance, and additional articles were obtained from their reference lists. Other sources of information were the websites of the European Medicines Agency, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Cochrane Library databases.

ANTI-TNF-α ANTIBODIES

A paradigm in management of IBD occurred in the late 90’s when the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, was identified as playing a pivotal role in the inflammatory cascade that orchestrate chronic intestinal inflammation[12], and is today the best studied pro-inflammatory cytokine in IBD.

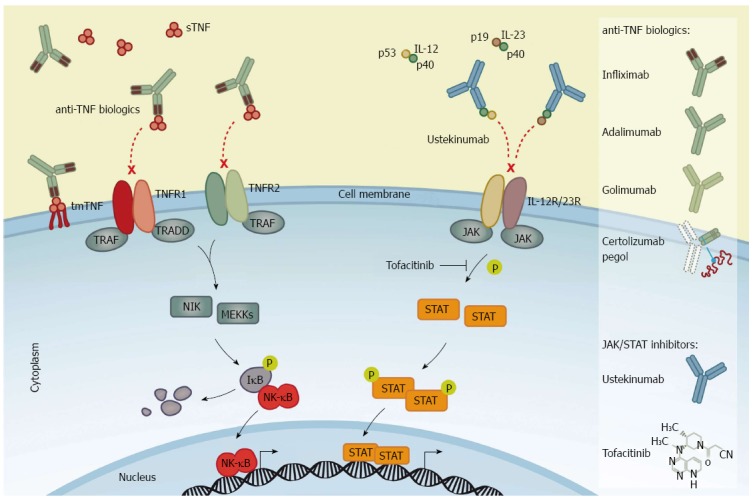

TNF-α is produced by mononuclear cells. Its synthesis is induced through activation of cellular receptors, e.g., the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). TLR4 is induced when derivates from the cell wall of Gram negative bacteria, lipopolysaccharides, bind to TLR4 on the surface of mononuclear cells. Activation of TLR4 signaling induces activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), causing an increased cell proliferation and differentiation of macrophages as well as inducing expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g., TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-12[13,14]. The TNF-α protein exists in two forms: the precursor transmembrane form (tmTNF-α, 26 kDa) and the secreted soluble form (sTNF-α, 17 kDa). When synthesised, homotrimeric TNF-α translocates to the cell membrane where the TNF-α-converting enzyme releases the sTNF-α from tmTNF-α by proteolytic cleavage. The biological activity of TNF-α is mediated by its binding to TNF receptor type 1 (TNFR1) and type 2 (TNFR2)[15]. After binding to the receptors, TNF-α initiates pro-inflammatory signaling by activation of the MAPKs and NF-κB pathways (Figure 1). Although, the active MAPKs and NF-κB signaling pathways are important for homeostasis, they induce cell proliferation, differentiation and up-regulation of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α during inflammation[16]. Additionally, TNF-α signaling induces caspase-8 activation and apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells through TNFR1 signaling[17], as well as inducing changes in the epithelial expression of tight junction proteins among patients with CD[18]. Hence increased TNF-α expression might decrease the mucosal barrier function in patients with IBD exacerbating the inflammation.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action of anti-tumor necrosis factor biologics and inhibitors of Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling. Left panel: Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biologics bind to homotrimeric TNF-α [transmembrane (tmTNF-α) and/or soluble (sTNF-α)], thereby blocking the interaction between the cytokine and TNF-α receptor type 1 and 2 (TNFR1 and TNFR2) to neutralise TNF-α-mediated pro-inflammatory signaling. Infliximab is shown as a representative anti-TNF biologics to illustrate the mechanism of action of the four agents labeled for IBD: Infliximab (a chimeric antibody), adalimumab and golimumab (fully human antibodies), and certolizumab pegol (a pegylated Fab fragment of a humanised anti-TNF antibody). Right panel: The fully human antibody against interleukin (IL)-12/23, ustekinumab, binds to the common p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23 heterodimers and prevents the interaction of IL-12 and IL-23 with their cognate receptors, IL-12R and IL-23R, hence neutralising IL-12/23-mediated intracellular signaling. Tofacitinib is a small molecule inhibitor of Janus kinase (JAK) activity that prevents the JAK-dependent phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins and subsequently the STAT-induced transcription of pro-inflammatory target genes.

Recent biologic therapies targeting TNF-α, with synthetic anti-TNF-α antibodies, have been shown to mitigate the inflammatory drive in chronic inflammatory conditions, including IBD. Initially, a chimeric (25% murine and 75% human sequence) IgG1κ subclass antibody, infliximab, that specifically binds TNF-α was shown to be beneficial in CD[19,20]. Attempts to reduce immunogenic responses induced by anti-chimeric antibodies included the removal of all murine sequences to create a fully human monoclonal antibody. This human IgG1 anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody, adalimumab, was also shown to be efficacious[21,22], as was a pegylated humanised antibody fragment (binding TNF-α) lacking the IgG1 Fc portion and conjugated with a 40-kDa polyethylene glycol molecule, certolizumab pegol (Figure 1)[23-25]. The observed efficacy in patients with CD provided a rationale for trials in patients with UC. Thus, in active stages of UC, an increased production of TNF-α by the mononuclear cells of the colonic lamina propria exists[26], with high concentrations of TNF-α found in rectal dialysates and stools[8]. Recent studies have shown another human IgG1 anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody, golimumab, to be efficient in UC[27]. However, the pharmacodynamics of TNFi seems to depend on the properties of the structure rather than simply the TNF-α-binding capacities. Eternacept, a non-antibody soluble recombinant TNF receptor (p75) Fc fusion protein, is not efficient for the treatment of intestinal inflammation[28]. The reason for this difference remains unclear although several mechanisms have been proposed. Hence, the underlying modes of action of the various TNF inhibitors are much more complex than initially thought[29]. The construct of the four TNFi’s labeled for IBD is shown in Figure 1.

Several placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated that infliximab[20,30], adalimumab[21,22,31], and certolizumab pegol[24] are efficacious in moderate to severe CD, as both first- and second-line therapy in patients with inadequate responses to standard treatment[32], including maintenance of response and remission[25,30,33,34]. Not only do TNFi reduce signs and symptoms of disease, but they also allow tapering of glucocorticoids (steroid-free remission)[21,30] and promote mucosal healing[35]. The former is considered a clinically relevant benefit, and the latter suggests a positive effect on disease progression. Infliximab is also labeled for use in fistulising CD[19,36].

In UC, randomised, controlled trials have shown infliximab[37], adalimumab[38,39], and golimumab[27,40] to be effective in inducing and maintaining clinical remission (including steroid-free remission) in patients with moderate to severe disease activity who have failed conventional therapy with glucocorticoids and thiopurines, and in the ACT2 study, infliximab also was effective in outpatients refractory to 5-ASA[37]. A post hoc analysis of the ACT1 and ACT2 studies showed that infliximab reduced the risk of colectomy after 1 year from 17% in the placebo group to 10% in the infliximab group (number needed to treat = 14)[41]. Furthermore, infliximab[37], adalimumab[39], and golimumab[27] additionally induced mucosal healing. Apart from use in patients with moderate chronic refractory UC, TNFi may be used as rescue therapy in hospitalised patients with severe UC. In a small placebo-controlled study, a single infusion of infliximab significantly reduced the number of colectomies among patients with an acute moderate to severe attack of UC[42], and this was also observed in a subsequent open-label randomised, controlled trial with a high number of steroid-refractory acute severe UC patients, leading to the conclusion that the effect of infliximab did not differ from that of cyclosporine[43].

The availability of TNFi has significantly altered the management of IBD in the last decade. The concomitant treatment with biologics and thiopurines proved in larger trials like the SONIC study to be superior for steroid-free clinical remission and absence of ulcerations (mucosal healing) at weeks 26 compared to monotherapy with either biologics or thiopurines in CD[44]. The UC SUCCESS trial[45] with a similar design and number of patients concluded the same, and the conclusion from both studies is that IBD patients in need of anti-TNF-α treatment should preferably receive combined treatment with a thiopurine. It should be emphasized that the use of potent immunomodulators (i.e., thiopurines[46]) in combination with TNFi is linked to an increased risk of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma[47]. Even though data are confounded by the fact that most patients with IBD on TNFi therapy receives concomitant therapy with thiopurines, no casual associations between TNFi alone and the development of lymphoma have been identified[11,47].

Although anti-TNF-α agents are the most effective anti-cytokine treatment in IBD a significant proportion of patients does not respond to induction therapy (i.e., “primary failures”) or loses the effect over time to become intolerant (i.e., “secondary failures”)[48]. The development of antibodies to the available biological agents is not only responsible for secondary loss of effect, but it is also associated with a risk of infusion reactions, although concomitant immunomodulator therapy may reduce the magnitude of the immunogenic response[48]. It has been shown that both adaption and switching from one TNFi to another can be efficacious to overcome resistance to anti-TNF-α treatment[48]. Nonetheless, there clearly remains an unmet need for novel treatment options in IBD.

Extraintestinal manifestations occur frequently with a negative impact of the quality of patients’ life[49]. Some extraintestinal manifestations such as arthritis, erythema nodosum, pyroderma gangraenosum, iritis, and uveitis have a pathogenic TNF-α-dependent mechanism common with CD and UC, and TNFi might additionally be applied in such cases to dampen inflammation[49].

JAK/STAT PATHWAY AND THERAPEUTIC ADVANCES IN IBD

Cytokines, which are small proteins produced by immune cells, facilitate communication between cells and have essential functions in cell development and differentiation. In addition to activate the NF-κB and MAPK pathways[16], a large number of mammalian cytokines exert their intracellular signaling by activating the JAK/STAT pathway[50]. The JAK/STAT pathway is an evolutionary conserved signaling network involved in a wide range of cellular processes, including cell growth, survival, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and inflammation[51]. There are four members of JAKs - JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) - that transduce signals through seven members of the STAT transcription factors - STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6 - in diverse combinations[50]. The diversity in cytokine responses is constituted by the combination of receptor binding to multiple JAKs and subsequent signaling through dimerised tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT variants. JAK1, JAK2, and TYK2 proteins can bind to various types of cytokine receptor families[50] and are expressed ubiquitously, whereas JAK3 is specifically associated with the IL-2R family [also known as the common γ-chain (γc) family which includes receptors for interleukins such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-13, IL-15, and IL-21] expressed only on hematopoietic cells[52-54]. In addition to the γc family of receptors, JAKs can be activated by the common β-chain family (known as the IL-3R family which includes receptors for e.g., IL-3 and IL-5), the receptors for IL-6, IL-11, IL-12, IL-23 and IL-27 cytokines which uses a glycoprotein-130 co-receptor (known as the IL-6R family), and the interferon (IFN)-R family [i.e., receptors for IFNs (IFN-α, -β, and -γ), IL-10, IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-25, and IL-26][50]. When STAT proteins become tyrosine-phosphorylated by JAKs they form homo- or heterodimers which translocate from the cytoplasm into the nucleus to regulate gene expression of target genes (Figure 1).

Tofacitinib (JAK inhibitor)

There has been great interest in development of small molecule inhibitors of intracellular signaling pathways related to various conditions, including IBD. Several genetic knockout studies have demonstrated the importance and essential functions of JAKs in cytokine signaling (reviewed in details in references[55-58]). Knockout of Jak1 or Jak2 genes are lethal in mice[59,60], whereas dysfunction of Jak3 or Tyk2 in both mice and humans causes primary immunodeficiency[61-64], underlying their importance for immune competence. Thus, the involvement of JAKs in a range of essential cytokine pathways has made JAK inhibitors a potential therapeutics target in IBD. Over the last two decades small-molecule JAK inhibitors have been synthesised and are currently under clinical investigation[65]. Tofacitinib (formerly known as CP-690,550) was the first selective JAK inhibitor to be tested in human clinical trials. Tofacitinib inhibits all four JAKs, however, with functional specificity for JAK1 and JAK3 in cellular assays[65,66]. Consequently, as a JAK1 and JAK3 inhibitor, tofacitinib effectively inhibits the signaling of the IL-2R family of cytokines[50,65] and the receptor for IL-6 family of cytokines including IL-12 and IL-23[53]. Tofacitinib also inhibits, albeit to a lesser extent, the IFN-R family[67] as well as the IL-3 and IL-5 receptors. Thus, tofacitinib affects both the innate and adaptive immune responses by suppressing differentiation of Th1 and Th2 cells and affecting the pathogenic Th17 cytokine production[65,68].

Tofacitinib is at present (September 2013) the only oral administered JAK inhibitor approved by FDA for use in therapy of adults with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, there are investigations indicating that the drug can be effective in treatment of other chronic inflammatory indications such as UC. In a double-bind randomised controlled phase II trial in UC, patients treated with oral tofacitinib showed higher clinical response after 8 wk compared with placebo[69]. The study comprised a total of 194 patients with moderate to severe UC receiving tofacitinib or placebo twice daily. Clinical response at 8 wk were found in 32%, 48%, 61%, and 78% of patients receiving twice daily tofacitinib at a dose of 0.5 mg (P = 0.39), 3 mg (P = 0.55), 10 mg (P = 0.10), and 15 mg (P < 0.001), respectively, as compared to 42% among patients receiving placebo[69]. Similarly, clinical remission at 8 wk were associated with a dose-dependent improvement of 13% (0.5 mg, P = 0.76), 33% (3 mg, P = 0.01), 48% (10 mg, P < 0.001), and 41% (15 mg, P < 0.001) as compared with 10% of patients receiving placebo[69]. Thus, tofacitinib seems effective and reasonably in patients with moderate to severe UC. In contrast, treatment of 139 randomised patients with moderate to severe CD with tofacitinib in a 4-wk phase II trial showed no clinical efficacy at doses of 1, 5, and 15 mg twice daily[70]. The underlying difference between the clinical efficacy of tofacitinib in UC and CD is unclear. With its oral route of administration, tofacitinib may offer a convenient alternative therapeutic option for UC patients who are refractory to conventional therapy such as anti-TNF-α therapy. However, larger long-term clinical studies with tofacitinib are required to report long-term safety as well as its therapeutic benefits in clinical use.

Ustekinumab (anti-IL-12/23 antibody)

One of the cytokine receptor families using the JAK/STAT signaling pathway is the IL-6 family of receptors. This receptor family includes receptors for IL-12 and IL-23 which are both heterodimeric cytokines consisting of two protein subunits, namely p35/p40 and p19/p40 subunits, respectively, hence sharing the p40 subunit[71]. IL-12 binds to the IL-12R which is composed of IL-12Rβ1 and IL-12Rβ2 subunits, whereas IL-23 binds to the IL-23R complex, composed of IL-23R and IL-12Rβ1[72].

The IL-12R is primarily expressed by activated T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells, but has been found to be expressed on dendritic cells (DCs) and B-cells as well[73,74]. IL-12 induces activated T-cells to differentiate into IFN-γ producing Th1 cells and it induces the NK cells to secrete IFN-γ and TNF-α[75,76]. The IL-23R is expressed on T-cells, but has also been found to be expressed by NK cells[72,77]. IL-23 primarily induces proliferation and survival of Th17 cells. Th17 cells secrete high amounts of IL-17 and IL-17F together with TNF-α, IL-6, IL-21 and IL-22. These cytokines have been found to be implicated in chronic inflammation as well as autoimmune diseases[78-81]. A study found IL-12 to be important for systemic activation of the immune system and IL-23 to drive local intestinal inflammation. Additionally, IL-23 was found to be involved in intestinal inflammation, because it was possible to reverse active colitis by administration of anti-IL-23, which might inhibit the pathogenic Th17 response, in a murine model[82]. In support of this, an increased expression of IL-23 and IL-17 has been found in the lamina propria of CD patients[83-85]. Likewise, overexpression of IL-12 and IL-23 has been found in the inflamed mucosa of CD patients[86-88]. Exactly how these two inflammatory cytokines contributes to the pathogenesis of CD has yet to be determined.

Ustekinumab is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody designed to bind to the p40 subunit common to both IL-12 and IL-23, thereby neutralising their activity (Figure 1). The binding of ustekinumab to free IL-12 and IL-23 cytokines block their interaction with IL-12Rβ1[89] expressed on T-cells, NK cells, macrophages, DCs, and B-cells. Ustekinumab was approved for treatment of psoriasis in 2009[90,91]. In recent years, testing of anti-IL-12/23 treatment in patients with CD has been performed. In a double-blind, cross-over phase II trial with moderate to severe CD, patients were divided into two populations; the first population (I) enrolled 104 patients who had previously received conventional or biologic therapy, and the second population (II) comprised patients whom were non-responders to infliximab[92]. In population I, 49% of ustekinumab treated patients were in clinical response after 8 wk (the primary end points) as compared to 40% of patients with placebo (P = 0.34). However, ustekinumab treatment was efficient in patients who had previously received infliximab (population II). Overall clinical response following 8 wk of ustekinumab treatment in population II was significantly greater than the group receiving placebo (P < 0.05). Hence, in the fall 2012, Sandborn et al[93] revealed a placebo-controlled phase II trial including 526 patients with moderate to severe CD who had all failed anti-TNF-α therapy. After 6 wk of randomised induction therapy (1, 3, or 6 mg/kg of body weight) or placebo, 145 patients had a clinical response to ustekinumab, as compared to placebo (1 mg, P = 0.02; 3 mg, P = 0.06; 6 mg, P = 0.005). At week 6, these 145 patients were enrolled in a second randomisation to receive either placebo or 90 mg ustekinumab at weeks 8 and 16 as a maintenance therapy. While the clinical remission rates in the induction therapy did not differ significantly from placebo at week 6, the maintenance therapy with ustekinumab every 8 wk resulted in significantly higher clinical remission at week 22 (42%), as compared with placebo (27%, P = 0.03). Therefore, ustekinumab may induce clinical response in moderate to severe CD among patients who are refractory to infliximab.

In order to demonstrate evidence of definitive effectiveness and safety of ustekinumab, phase III trials are needed to test the long-term effects of ustekinumab as well as possible side effects. Three phase III trials are currently under way. They include an induction trial in patients with moderate to severe CD who are either naïve to anti-TNF-α treatment or have previously failed anti-TNF-α treatment as well as a maintenance trial in patients who respond to induction treatment with ustekinumab[94].

TRAFFICKING OF THE IMMUNE CELLS TO THE INTESTINE

Following pathogen invasion of the intestinal mucosa and initiation of an immunogenic response, a priming of effector cells occurs in the Peyer’s patches or in the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs). After the T-cell priming and release into the circulation, specific adhesion molecules are required for the cells to home to the site of inflammation. Important adhesion molecules in the homing to the intestines are the chemokine receptor 9 (CCR9) and the integrins α4β1 and α4β7, which are all induced on intestinal mucosal T-cells following activation and imprinting of gut-homing specificity[95,96].

The homing of immune cells to the intestine during inflammation has become a major target in the treatment of IBD. In order to reduce leukocyte infiltration and continuation of inflammation, a number of molecules have been targeted by antibodies and small molecules to block these adhesion molecules[3].

Natalizumab and vedolizumab (Integrin blocking antibodies)

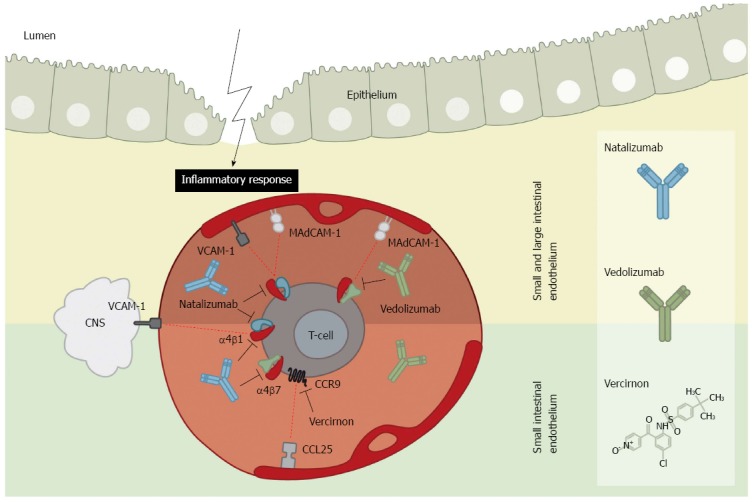

In mammals, 18 α-integrin and 8 β-integrin subtypes have been discovered which are able to assemble into at least 24 individual integrin heterodimers[97]. Of importance for IBD are two integrin heterodimers, namely α4β1 and α4β7, which at present have been utilised for treatment. Following inflammation of the small or large intestine a significant increase is observed in the endothelial expression of both ligands of these integrins. These are the mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1)[98] and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1)[99], respectively. The primed leukocytes in the circulation are in this way recruited to the inflamed intestine in UC and CD, where they are able to extravasate the endothelium to reach the site of inflammation.

The first drug to be approved for targeting cell adhesion molecules in IBD was natalizumab, a recombinant humanised monoclonal IgG4k antibody (Figure 2). It has in some countries been approved for CD[100], for both induction and maintenance indications. Natalizumab is an antibody targeting the α4 integrin subunit, hence targeting both the α4β1 and the α4β7 integrin heterodimers[101,102] (Figure 2). The ligands of these two integrins are located on the endothelium in the intestinal lamina propria, but additionally the α4β1 integrin is also involved in targeting of leukocytes to the central nervous system (CNS) through interaction with endothelial VCAM-1[96,103] (Figure 2). Natalizumab has for this reason been approved for multiple sclerosis (MS) due to its ability to limit neuronal inflammation and to reduce the risk of progressing disability[100,104]. This effect of natalizumab on blocking leukocyte adhesion to the CNS is considered to be a side effect as it thereby inhibits immune surveillance of the CNS. Three cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in patients on natalizumab have been reported among two patients with MS receiving concomitant IFN-β-1α[103,105], and one patient with CD on monotherapy[106]. Following blockade of the leukocyte recruitment and patrolling of the CNS, these patients experienced a reactivation or infection of the opportunistic JC virus leading to PML. Hence, natalizumab is today used as a second-line therapy, and patients might be screened for JC virus infection prior to treatment and are not allowed to be on concomitant immunomodulators[100].

Figure 2.

Integrin and chemokine inhibitors in intestinal endothelium. Mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) and vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) adhesion molecules become up-regulated on the endothelium during intestinal inflammation. In the small and large intestine (upper panel) the adhesion molecule MAdCAM-1 functions as docking site for integrins α4β1 and α4β7 expressed by T-cells. Contrary, the adhesion molecule VCAM-1 also acts as docking molecule for α4β1. Addition of the inhibitory α4β1 antibody, natalizumab, thus blocks adhesion of T-cells to the entire intestinal mucosa. As VCAM-1 is additionally expressed within the central nervous system (CNS), natalizumab also blocks T-cell extravasation and hence limits immune surveillance of the CNS which might lead to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Using the α4β7 inhibitory antibody, vedolizumab, only the adhesion of T-cells to the intestine specific MAdCAM-1 is blocked, and thus does not limit immune surveillance of the CNS while dampening the inflammatory response. In the endothelium of the small intestine (lower panel) the chemokine ligand 25 (CCL25) adhesion molecule is predominantly expressed during inflammation. It acts as a ligand for the chemokine receptor 9 (CCR9) on T-cells. The inhibitor vercirnon blocks the CCL25-CCR9 chemotaxis thus inhibiting T-cells adhesion to the small intestinal mucosa. Vercirnon was recently withdrawn following a phase III trial.

Natalizumab is today the only available biological therapy for CD not targeting TNF-α and have shown convincing results. In the final randomised placebo-controlled phase III study, 509 patients with moderate to severe CD experienced clinical response rates by week 4 of 51% and 37% (P = 0.001) for natalizumab and placebo treatment, respectively, falling to 48% and 32% at week 8 (P < 0.001) (300 mg natalizumab or placebo at weeks 0, 4, and 8). Sustained remission occurred in 26% vs 16% of the patients following week 12 (P = 0.002)[102]. A meta-analysis performed on 5 randomised controlled trials of natalizumab has furthermore shown natalizumab to be superior to placebo[107].

Due to the risk of PML following natalizumab treatment, more specific antibodies are, however, warranted. Vedolizumab is a humanised monoclonal IgG1 antibody specific for the α4β7 integrin, hence blocking leukocyte adhesion to MAdCAM-1 expressed solely by the gut endothelium[103] (Figure 2). On the basis of the phase III study series for vedolizumab (GEMINI Studies™) Takeda filed a Biologics License Application (BLA) to the FDA for use in both UC and CD in the early summer of 2013[108]. Years back, randomised placebo-controlled phase II trials showed clinical effect of a monoclonal antibody similar to vedolizumab on both CD and UC[109,110]. Results from the GEMINI series (with GEMINI III and GEMINI LTS still ongoing) showed that patients with UC, responding to vedolizumab induction therapy, receiving 300 mg vedolizumab every 4 or 8 wk for 52 wk had remission rates of 49% (P < 0.001) and 42% (P < 0.001), respectively, compared to remission rates of 16% in the placebo group. Following a 6 wk induction period the clinical remission rates were 47% vs 26%, respectively for vedolizumab over placebo (P < 0.001)[111]. For CD, a clinical remission rate of 15% compared to 7% (P = 0.02) was observed for vedolizumab (300 mg) compared to placebo following 6 wk induction treatment. Prolonged treatment of responders with vedolizumab every 4 or 8 wk over the following 52 wk showed clinical remission rates of 36% (P = 0.004) and 39% (P < 0.001), respectively, compared to 22% in the placebo group[112].

There are no concerns for PML in relation to vedolizumab as it does not seem to influence the immune surveillance of the CNS in contrast to natalizumab[103,113]. There are high expectations to vedolizumab which is the only gut selective drug for treatment of IBD, and it may potentially be used as either a secondary intervention following anti-TNF-α failure or as a first-line treatment.

Integrins are important in the process of cellular adhesion underlying the mechanism of action for the integrin blocking antibodies. Integrins do, however, also transmit cellular signaling. Evidence suggests that the interaction of the α4 integrins (α4β1 and α4β7) with their ligands lead to the binding of its cytosolic domain to paxillin, an intracellular signaling adaptor protein[114]. Hence, paxillin is a part of the focal adhesion complex and gets phosphorylated by focal adhesion kinase and Src kinase as well as other kinases including c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) and p38 MAPK[115]. Mutations of the cytoplasmic tail of α4 integrin disrupts the paxillin binding site and lead to a reduced recruitment of mononuclear leukocytes to the site of thioglycollate-induced peritonitis[116], although the integrin binding to its ligands was unaffected. This evidence suggests that in particular the α4 integrin signaling might influence the leukocyte homing to the inflamed section of the gastrointestinal tract or may even play part in the full T-cell activation process by blockade of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) signaling, despite the major effect as being an adhesion molecule itself[115]. These findings may provide insight to the discipline of regulating the inflammatory response; however, this specific area needs further investigation.

Vercirnon (chemokine receptor inhibitor)

In addition to integrins, CCR9 (a G-protein coupled receptor) also play a role in immune cell recruitment to the intestine by exerting a chemotatic response towards chemokine ligand 25 (CCL25)[117]. CCR9 is preferentially expressed on thymocytes[118] as well as on intraepithelial and lamina propria lymphocytes of the small intestine[119]. CCL25 is considered a potential intestine-specific homing ligand expressed both within the crypts of the intestinal epithelium[120], and on the vascular endothelium within the human small intestine[121,122]. CCL25 is also expressed in the colon but in much lower levels as compared to the small intestine[123].

The involvement of CCR9 in lymphocyte trafficking to the small intestine was initially suggested by the fact that CCR9 is selectively expressed on gut-homing T-cells[124]. The CCR9+ T cells have also been found to be elevated in the peripheral blood of CD patients, but not in patients with CD solely confined to the colon[125]. In this context, inhibition of CCL25/CCR9 chemotaxis has been suggested to be an attractive target for CD of the small intestine. Oral administration of vercirnon (GSK-1605786A), a selective small-molecule antagonist of CCR9 that inhibits CCR9- and CCL25-dependent chemotaxis (Figure 2) in an experimental mouse model demonstrated a clear therapeutic benefit by leading to significantly reduced inflammation in these mice[126,127]. In addition, in vitro experiments with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells showed that vercirnon is a selective and potent antagonist of human CCR9[126] and inhibits both functional variants of CCR9 (CCR9A and CCR9B)[126,128]. Based on these findings, several clinical double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trials (reviewed in reference[127]) have been conducted for shorter and longer induction periods with vercirnon in patients with moderate to severe CD. The clinical remission rate following 36 wk of vercirnon treatment with 250 mg twice daily was 47% as compared to 31% in the placebo group. In addition, the levels of C-reactive protein were normalised in 19% of subjects receiving vercirnon compared with only 9% of individuals given placebo[127]. In a recent study the expression of CCR9 was also observed on activated regulatory T-cells and is important for trafficking these cells to the inflamed site of the intestine[129] suggesting that inhibition of CCR9- and CCL25-dependent chemotaxis may result in a dysfunctional immune response and consequently exacerbation of CD. Moreover, a newly published clinical double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter phase II trial (Prospective Randomized Oral-Therapy Evaluation in Crohn’s disease Trial-1) for assessing the efficacy and safety of vercirnon in moderate to severe CD patients showed that vercirnon was well tolerated with no elevated risk of disease exacerbation compared to placebo[130]. However, in September 2013, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) decided to terminate all clinical trials with vercirnon as it failed in the first phase III study, SHIELD-1, both the primary endpoint of improved clinical response as well as the key secondary endpoint of clinical remission. SHIELD-1 was a randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of two doses (500 mg once daily and 500 mg twice daily) of vercirnon compared to placebo over 12 wk in 608 adults with moderate to severe CD. The study showed no efficacy with either dose in inducing a clinical response or remission. Moreover, increased rates of adverse events of vercirnon, including gastrointestinal- and cardiac disorders as compared to placebo were reported.

CONCLUSION

In recent years progress in basic and translational research has led to better understanding of the role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of IBD. It is believed that an altered balance between regulatory and inflammatory cytokines contributes to perpetuate the mucosal inflammation in both CD and UC. Since there is evidence that the tissue damaging immune response is driven by multiple cytokine driven inflammatory pathways, it is logical to hypothesise that simultaneously targeting two or more of these signals could be more advantageous than inhibiting just selective single pathways. Various approaches for inhibiting such pathways have been developed and are ready to go into the clinic. However, in designing clinical interventions around these new drugs it should be taken into consideration that inhibition of inflammatory cytokines could be associated with severe side-effects, as these molecules are also involved in the regulation of physiological processes and immune responses against infections and neoplasias. Another promising therapeutic strategy is to restore counter regulatory mechanisms which are defective in IBD. Since it is conceivable that no drug fits all patients, further experiments will be necessary to identify biomarkers that predict responsiveness to the anti-cytokine based therapy as well as to ascertain which biological therapy will be most effective for the individual patient (i.e., tailored therapy).

Analysis of immuno-inflammatory pathways in the gut of patients with CD and UC have shown that tissue damage is driven by complex and dynamic cross-talk between immune and non-immune cells, and that cytokines are key mediators of this interplay[1,131]. Considerable efforts have furthermore been used on the regulation of the inflammatory cellular invasion into the lamina propria to break the continuous pathogenic cytokine signaling. It has been demonstrated that some cytokine mediated counter-regulatory anti-inflammatory pathways are defect in IBD raising the possibility that restoring these anti-inflammatory signals may be a therapeutic strategy. These advances together with several experimental models of intestinal inflammation have facilitated the development of components and biologics that neutralise cytokines. Some of these drugs have already been tested in patients with IBD and others are ready to move into clinical trials. However, given the plethora of immunological manipulations that can prevent colitis in experimental models, the recent failures of anti-IFN-γ, and anti-IL-17 antibodies as well as the antagonist of CCR9 in the clinical setting, and the fact that only 66% and 50% of patients with CD and UC, respectively, respond to anti-TNF-α therapy, it now becomes extremely difficult to decide which other cytokines/chemokines should be targeted, and if they will ever beat TNFi[132].

Footnotes

Supported by Grants from the Foundation of Aase and Ejnar Danielsen, the Foundation of Axel Muusfeldt, and the A P Møller Foundation (“Fonden til Lægevidenskabens Fremme”)

P- Reviewers: Arias M, AzumaYT, Jiang M, Yamamoto S S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danese S. New therapies for inflammatory bowel disease: from the bench to the bedside. Gut. 2012;61:918–932. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murch SH, Lamkin VA, Savage MO, Walker-Smith JA, MacDonald TT. Serum concentrations of tumour necrosis factor alpha in childhood chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1991;32:913–917. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.8.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald TT, Hutchings P, Choy MY, Murch S, Cooke A. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma production measured at the single cell level in normal and inflamed human intestine. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;81:301–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb03334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breese EJ, Michie CA, Nicholls SW, Murch SH, Williams CB, Domizio P, Walker-Smith JA, MacDonald TT. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-producing cells in the intestinal mucosa of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1455–1466. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braegger CP, Nicholls S, Murch SH, Stephens S, MacDonald TT. Tumour necrosis factor alpha in stool as a marker of intestinal inflammation. Lancet. 1992;339:89–91. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90999-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen OH, Gionchetti P, Ainsworth M, Vainer B, Campieri M, Borregaard N, Kjeldsen L. Rectal dialysate and fecal concentrations of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2923–2928. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saiki T, Mitsuyama K, Toyonaga A, Ishida H, Tanikawa K. Detection of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in stools of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:616–622. doi: 10.1080/00365529850171891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen OH, Rask-Madsen J. Mediators of inflammation in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;216:149–159. doi: 10.3109/00365529609094569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen OH, Ainsworth MA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:754–762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1209614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ordás I, Mould DR, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: pharmacokinetics-based dosing paradigms. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:635–646. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart AL, Al-Hassi HO, Rigby RJ, Bell SJ, Emmanuel AV, Knight SC, Kamm MA, Stagg AJ. Characteristics of intestinal dendritic cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:50–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu YC, Yeh WC, Ohashi PS. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine. 2008;42:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croft M, Benedict CA, Ware CF. Clinical targeting of the TNF and TNFR superfamilies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:147–168. doi: 10.1038/nrd3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coskun M, Olsen J, Seidelin JB, Nielsen OH. MAP kinases in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulzke JD, Bojarski C, Zeissig S, Heller F, Gitter AH, Fromm M. Disrupted barrier function through epithelial cell apoptosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1072:288–299. doi: 10.1196/annals.1326.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D, Richter J, Mankertz J, Wahnschaffe U, Kroesen AJ, Zeitz M, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2007;56:61–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.094375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, Schaible TF, Rutgeerts PJ. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Byczkowski D, Li J, Kent JD, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh D, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Pollack P. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323–333; quiz 591. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandborn WJ, Abreu MT, D’Haens G, Colombel JF, Vermeire S, Mitchev K, Jamoul C, Fedorak RN, Spehlmann ME, Wolf DC, et al. Certolizumab pegol in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease and secondary failure to infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:688–695.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Stoinov S, Honiball PJ, Rutgeerts P, Mason D, Bloomfield R, Schreiber S. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:228–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreiber S, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Lawrance IC, Thomsen OØ, Hanauer SB, McColm J, Bloomfield R, Sandborn WJ. Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713–1725. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1102942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, Zhang H, Strauss R, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Guzzo C, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, et al. Subcutaneous Golimumab Induces Clinical Response and Remission in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:85–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Katz S, Safdi M, Wolf DG, Baerg RD, Tremaine WJ, Johnson T, Diehl NN, Zinsmeister AR. Etanercept for active Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1088–1094. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coskun M, Nielsen OH. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2561–2562. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1312800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Colombel JF, Panaccione R, D’Haens G, Li J, Rosenfeld MR, Kent JD, et al. Adalimumab induction therapy for Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:829–838. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, Branche J, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn’s disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lichtenstein GR, Thomsen OØ, Schreiber S, Lawrance IC, Hanauer SB, Bloomfield R, Sandborn WJ. Continuous therapy with certolizumab pegol maintains remission of patients with Crohn’s disease for up to 18 months. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:600–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh DG, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Kent JD, Bittle B, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. 2007;56:1232–1239. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619–1635. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW, D’Haens G, Hanauer S, Schreiber S, Panaccione R, Fedorak RN, Tighe MB, Huang B, et al. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60:780–787. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.221127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, D’Haens G, Wolf DC, Kron M, Tighe MB, Lazar A, Thakkar RB. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257–65.e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, Zhang H, Strauss R, Johanns J, Adedokun OJ, Guzzo C, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, et al. Subcutaneous Golimumab Maintains Clinical Response in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:96–109.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Lu J, Horgan K, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, et al. Colectomy rate comparison after treatment of ulcerative colitis with placebo or infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1250–1260; quiz 1520. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Järnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-Liby I, Blomquist L, Karlén P, Grännö C, Vilien M, Ström M, Danielsson A, Verbaan H, et al. Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1805–1811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, Allez M, Bouhnik Y, Filippi J, Zerbib F, Savoye G, Nachury M, Moreau J, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1909–1915. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D’Haens G, Diamond RH, Broussard DL, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, Marques JR, Khalif I, Flint L, van Hoogstraten H, Zheng H, Danese S, Rutgeerts PJ. Infliximab, azathioprine, or infliximab azathioprine for treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: the UC SUCCESS trial. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(suppl 1):S134. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nielsen OH, Bjerrum JT, Herfarth H, Rogler G. Recent advances using immunomodulators for inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53:575–588. doi: 10.1002/jcph.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subramaniam K, D’Rozario J, Pavli P. Lymphoma and other lymphoproliferative disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: a review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:24–30. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nielsen OH, Seidelin JB, Munck LK, Rogler G. Use of biological molecules in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Intern Med. 2011;270:15–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larsen S, Bendtzen K, Nielsen OH. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Ann Med. 2010;42:97–114. doi: 10.3109/07853890903559724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coskun M, Salem M, Pedersen J, Nielsen OH. Involvement of JAK/STAT signaling in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013;76:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liongue C, O’Sullivan LA, Trengove MC, Ward AC. Evolution of JAK-STAT pathway components: mechanisms and role in immune system development. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu W, Sun XH. Janus kinase 3: the controller and the controlled. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2012;44:187–196. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cornejo MG, Boggon TJ, Mercher T. JAK3: a two-faced player in hematological disorders. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:2376–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Igaz P, Tóth S, Falus A. Biological and clinical significance of the JAK-STAT pathway; lessons from knockout mice. Inflamm Res. 2001;50:435–441. doi: 10.1007/PL00000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schindler C, Plumlee C. Inteferons pen the JAK-STAT pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiu H, Nicholson SE. Biology and significance of the JAK/STAT signalling pathways. Growth Factors. 2012;30:88–106. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2012.660936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Shea JJ, Holland SM, Staudt LM. JAKs and STATs in immunity, immunodeficiency, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:161–170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodig SJ, Meraz MA, White JM, Lampe PA, Riley JK, Arthur CD, King KL, Sheehan KC, Yin L, Pennica D, et al. Disruption of the Jak1 gene demonstrates obligatory and nonredundant roles of the Jaks in cytokine-induced biologic responses. Cell. 1998;93:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neubauer H, Cumano A, Müller M, Wu H, Huffstadt U, Pfeffer K. Jak2 deficiency defines an essential developmental checkpoint in definitive hematopoiesis. Cell. 1998;93:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suzuki K, Nakajima H, Saito Y, Saito T, Leonard WJ, Iwamoto I. Janus kinase 3 (Jak3) is essential for common cytokine receptor gamma chain (gamma(c))-dependent signaling: comparative analysis of gamma(c), Jak3, and gamma(c) and Jak3 double-deficient mice. Int Immunol. 2000;12:123–132. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karaghiosoff M, Neubauer H, Lassnig C, Kovarik P, Schindler H, Pircher H, McCoy B, Bogdan C, Decker T, Brem G, et al. Partial impairment of cytokine responses in Tyk2-deficient mice. Immunity. 2000;13:549–560. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Macchi P, Villa A, Giliani S, Sacco MG, Frattini A, Porta F, Ugazio AG, Johnston JA, Candotti F, O’Shea JJ. Mutations of Jak-3 gene in patients with autosomal severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) Nature. 1995;377:65–68. doi: 10.1038/377065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leonard WJ, O’Shea JJ. Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:293–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ghoreschi K, Jesson MI, Li X, Lee JL, Ghosh S, Alsup JW, Warner JD, Tanaka M, Steward-Tharp SM, Gadina M, et al. Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by tofacitinib (CP-690,550) J Immunol. 2011;186:4234–4243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams NK, Bamert RS, Patel O, Wang C, Walden PM, Wilks AF, Fantino E, Rossjohn J, Lucet IS. Dissecting specificity in the Janus kinases: the structures of JAK-specific inhibitors complexed to the JAK1 and JAK2 protein tyrosine kinase domains. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Müller M, Briscoe J, Laxton C, Guschin D, Ziemiecki A, Silvennoinen O, Harpur AG, Barbieri G, Witthuhn BA, Schindler C. The protein tyrosine kinase JAK1 complements defects in interferon-alpha/beta and -gamma signal transduction. Nature. 1993;366:129–135. doi: 10.1038/366129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoshida H, Kimura A, Fukaya T, Sekiya T, Morita R, Shichita T, Inoue H, Yoshimura A. Low dose CP-690,550 (tofacitinib), a pan-JAK inhibitor, accelerates the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by potentiating Th17 differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, Vranic I, Su C, Rousell S, Niezychowski W. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in active ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:616–624. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, Vranic I, Spanton J, Niezychowski W. Phase 2 Randomized Study of CP-690,550, an Oral Janus Kinase Inhibitor, in Active Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S124. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, Hewick RM, Clark SC, Chan S, Loudon R, Sherman F, Perussia B, Trinchieri G. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biologic effects on human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:827–845. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, Vaisberg E, Travis M, Cheung J, Pflanz S, Zhang R, Singh KP, Vega F, et al. A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rbeta1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J Immunol. 2002;168:5699–5708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Benson JM, Sachs CW, Treacy G, Zhou H, Pendley CE, Brodmerkel CM, Shankar G, Mascelli MA. Therapeutic targeting of the IL-12/23 pathways: generation and characterization of ustekinumab. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:615–624. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:133–146. doi: 10.1038/nri1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kikly K, Liu L, Na S, Sedgwick JD. The IL-23/Th(17) axis: therapeutic targets for autoimmune inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perussia B, Chan SH, D’Andrea A, Tsuji K, Santoli D, Pospisil M, Young D, Wolf SF, Trinchieri G. Natural killer (NK) cell stimulatory factor or IL-12 has differential effects on the proliferation of TCR-alpha beta+, TCR-gamma delta+ T lymphocytes, and NK cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:3495–3502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cua DJ, Sherlock J, Chen Y, Murphy CA, Joyce B, Seymour B, Lucian L, To W, Kwan S, Churakova T, et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421:744–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abraham C, Cho JH. IL-23 and autoimmunity: new insights into the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:97–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.051407.123757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iwakura Y, Ishigame H. The IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1218–1222. doi: 10.1172/JCI28508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smits HH, van Beelen AJ, Hessle C, Westland R, de Jong E, Soeteman E, Wold A, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. Commensal Gram-negative bacteria prime human dendritic cells for enhanced IL-23 and IL-27 expression and enhanced Th1 development. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1371–1380. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nishimoto N. Interleukin-6 in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:277–281. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000218949.19860.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Elson CO, Cong Y, Weaver CT, Schoeb TR, McClanahan TK, Fick RB, Kastelein RA. Monoclonal anti-interleukin 23 reverses active colitis in a T cell-mediated model in mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2359–2370. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uhlig HH, McKenzie BS, Hue S, Thompson C, Joyce-Shaikh B, Stepankova R, Robinson N, Buonocore S, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Cua DJ, et al. Differential activity of IL-12 and IL-23 in mucosal and systemic innate immune pathology. Immunity. 2006;25:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aggarwal S, Ghilardi N, Xie MH, de Sauvage FJ, Gurney AL. Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1910–1914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hölttä V, Klemetti P, Sipponen T, Westerholm-Ormio M, Kociubinski G, Salo H, Räsänen L, Kolho KL, Färkkilä M, Savilahti E, et al. IL-23/IL-17 immunity as a hallmark of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1175–1184. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schmidt C, Giese T, Ludwig B, Mueller-Molaian I, Marth T, Zeuzem S, Meuer SC, Stallmach A. Expression of interleukin-12-related cytokine transcripts in inflammatory bowel disease: elevated interleukin-23p19 and interleukin-27p28 in Crohn’s disease but not in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:16–23. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fuss IJ, Becker C, Yang Z, Groden C, Hornung RL, Heller F, Neurath MF, Strober W, Mannon PJ. Both IL-12p70 and IL-23 are synthesized during active Crohn’s disease and are down-regulated by treatment with anti-IL-12 p40 monoclonal antibody. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:9–15. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000194183.92671.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Parrello T, Monteleone G, Cucchiara S, Monteleone I, Sebkova L, Doldo P, Luzza F, Pallone F. Up-regulation of the IL-12 receptor beta 2 chain in Crohn’s disease. J Immunol. 2000;165:7234–7239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Luo J, Wu SJ, Lacy ER, Orlovsky Y, Baker A, Teplyakov A, Obmolova G, Heavner GA, Richter HT, Benson J. Structural basis for the dual recognition of IL-12 and IL-23 by ustekinumab. J Mol Biol. 2010;402:797–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leonardi CL, Kimball AB, Papp KA, Yeilding N, Guzzo C, Wang Y, Li S, Dooley LT, Gordon KB. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1) Lancet. 2008;371:1665–1674. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60725-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Papp KA, Langley RG, Lebwohl M, Krueger GG, Szapary P, Yeilding N, Guzzo C, Hsu MC, Wang Y, Li S, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 2) Lancet. 2008;371:1675–1684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Scherl E, Fleisher MR, Katz S, Johanns J, Blank M, Rutgeerts P. A randomized trial of Ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1130–1141. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, Gao LL, Blank MA, Johanns J, Guzzo C, Sands BE, Hanauer SB, Targan S, Rutgeerts P, et al. Ustekinumab induction and maintenance therapy in refractory Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1519–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ray K. IBD: Ustekinumab shows promise in the treatment of refractory Crohn’s disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:690. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, Song SY. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sheridan BS, Lefrançois L. Regional and mucosal memory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:485–491. doi: 10.1038/ni.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takada Y, Ye X, Simon S. The integrins. Genome Biol. 2007;8:215. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ando T, Langley RR, Wang Y, Jordan PA, Minagar A, Alexander JS, Jennings MH. Inflammatory cytokines induce MAdCAM-1 in murine hepatic endothelial cells and mediate alpha-4 beta-7 integrin dependent lymphocyte endothelial adhesion in vitro. BMC Physiol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Panés J, Granger DN. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions: molecular mechanisms and implications in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1066–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.FDA Approval of Natalizumab for use in Crohn’s disease. 2008. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2008/125104s0033ltr.pdf.

- 101.Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Enns R, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lawrance IC, Panaccione R, Sanders M, Schreiber S, Targan S, et al. Natalizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1912–1925. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Targan SR, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Lashner BA, Panaccione R, Present DH, Spehlmann ME, Rutgeerts PJ, Tulassay Z, Volfova M, et al. Natalizumab for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: results of the ENCORE Trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1672–1683. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Haanstra KG, Hofman SO, Lopes Estêvão DM, Blezer EL, Bauer J, Yang LL, Wyant T, Csizmadia V, ‘t Hart BA, Fedyk ER. Antagonizing the α4β1 integrin, but not α4β7, inhibits leukocytic infiltration of the central nervous system in rhesus monkey experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2013;190:1961–1973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E, Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Miller DH, Phillips JT, Lublin FD, Giovannoni G, Wajgt A, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:899–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:369–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, Dubois B, Vermeire S, Noman M, Verbeeck J, Geboes K, Robberecht W, Rutgeerts P. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:362–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:644–59, quiz 660. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Available from: http://www.drugs.com/nda/vedolizumab_130621.html.

- 109.Feagan BG, Greenberg GR, Wild G, Fedorak RN, Paré P, McDonald JW, Dubé R, Cohen A, Steinhart AH, Landau S, et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with a humanized antibody to the alpha4beta7 integrin. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2499–2507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Feagan BG, Greenberg GR, Wild G, Fedorak RN, Paré P, McDonald JW, Cohen A, Bitton A, Baker J, Dubé R, et al. Treatment of active Crohn’s disease with MLN0002, a humanized antibody to the alpha4beta7 integrin. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1370–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Van Assche G, Axler J, Kim HJ, Danese S, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Lukas M, Fedorak RN, Lee S, Bressler B, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fedyk ER, Wyant T, Yang LL, Csizmadia V, Burke K, Yang H, Kadambi VJ. Exclusive antagonism of the α4 β7 integrin by vedolizumab confirms the gut-selectivity of this pathway in primates. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2107–2119. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Liu S, Thomas SM, Woodside DG, Rose DM, Kiosses WB, Pfaff M, Ginsberg MH. Binding of paxillin to alpha4 integrins modifies integrin-dependent biological responses. Nature. 1999;402:676–681. doi: 10.1038/45264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lee YC, Chang AY, Lin-Feng MH, Tsou WI, Chiang IH, Lai MZ. Paxillin phosphorylation by JNK and p38 is required for NFAT activation. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:2165–2175. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kummer C, Petrich BG, Rose DM, Ginsberg MH. A small molecule that inhibits the interaction of paxillin and alpha 4 integrin inhibits accumulation of mononuclear leukocytes at a site of inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9462–9469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zaballos A, Gutiérrez J, Varona R, Ardavín C, Márquez G. Cutting edge: identification of the orphan chemokine receptor GPR-9-6 as CCR9, the receptor for the chemokine TECK. J Immunol. 1999;162:5671–5675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Norment AM, Bogatzki LY, Gantner BN, Bevan MJ. Murine CCR9, a chemokine receptor for thymus-expressed chemokine that is up-regulated following pre-TCR signaling. J Immunol. 2000;164:639–648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lefrançois L, Lycke N. Isolation of mouse small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, Peyer’s patch, and lamina propria cells. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;Chapter 3:Unit 3.19. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0319s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.White GE, Iqbal AJ, Greaves DR. CC chemokine receptors and chronic inflammation--therapeutic opportunities and pharmacological challenges. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:47–89. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kunkel EJ, Campbell JJ, Haraldsen G, Pan J, Boisvert J, Roberts AI, Ebert EC, Vierra MA, Goodman SB, Genovese MC, et al. Lymphocyte CC chemokine receptor 9 and epithelial thymus-expressed chemokine (TECK) expression distinguish the small intestinal immune compartment: Epithelial expression of tissue-specific chemokines as an organizing principle in regional immunity. J Exp Med. 2000;192:761–768. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Papadakis KA, Prehn J, Nelson V, Cheng L, Binder SW, Ponath PD, Andrew DP, Targan SR. The role of thymus-expressed chemokine and its receptor CCR9 on lymphocytes in the regional specialization of the mucosal immune system. J Immunol. 2000;165:5069–5076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wurbel MA, McIntire MG, Dwyer P, Fiebiger E. CCL25/CCR9 interactions regulate large intestinal inflammation in a murine model of acute colitis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zabel BA, Agace WW, Campbell JJ, Heath HM, Parent D, Roberts AI, Ebert EC, Kassam N, Qin S, Zovko M, et al. Human G protein-coupled receptor GPR-9-6/CC chemokine receptor 9 is selectively expressed on intestinal homing T lymphocytes, mucosal lymphocytes, and thymocytes and is required for thymus-expressed chemokine-mediated chemotaxis. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1241–1256. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Papadakis KA, Prehn J, Moreno ST, Cheng L, Kouroumalis EA, Deem R, Breaverman T, Ponath PD, Andrew DP, Green PH, et al. CCR9-positive lymphocytes and thymus-expressed chemokine distinguish small bowel from colonic Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:246–254. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Walters MJ, Wang Y, Lai N, Baumgart T, Zhao BN, Dairaghi DJ, Bekker P, Ertl LS, Penfold ME, Jaen JC, et al. Characterization of CCX282-B, an orally bioavailable antagonist of the CCR9 chemokine receptor, for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:61–69. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.169714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Eksteen B, Adams DH. GSK-1605786, a selective small-molecule antagonist of the CCR9 chemokine receptor for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. IDrugs. 2010;13:472–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yu CR, Peden KW, Zaitseva MB, Golding H, Farber JM. CCR9A and CCR9B: two receptors for the chemokine CCL25/TECK/Ck beta-15 that differ in their sensitivities to ligand. J Immunol. 2000;164:1293–1305. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wermers JD, McNamee EN, Wurbel MA, Jedlicka P, Rivera-Nieves J. The chemokine receptor CCR9 is required for the T-cell-mediated regulation of chronic ileitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1526–35.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Keshav S, Vaňásek T, Niv Y, Petryka R, Howaldt S, Bafutto M, Rácz I, Hetzel D, Nielsen OH, Vermeire S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of CCX282-B, an orally-administered blocker of chemokine receptor CCR9, for patients with Crohn’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Macdonald TT, Monteleone G. Immunity, inflammation, and allergy in the gut. Science. 2005;307:1920–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.1106442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S, Van Assche G. Biological therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1182–1197. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]