Abstract

Background

Promotion for academic faculty depends on a variety of factors, including their research, publications, national leadership, and quality of their teaching.

Objective

We sought to determine the importance of resident evaluations of faculty for promotion in obstetrics-gynecology programs.

Methods

A 28-item questionnaire was developed and distributed to 185 department chairs of US obstetrics-gynecology residency programs.

Results

Fifty percent (93 of 185) responded, with 40% (37 of 93) stating that teaching has become more important for promotion in the past 10 years. When faculty are being considered for promotion, teaching evaluations were deemed “very important” 60% of the time for clinician track faculty but were rated as mainly “not important” or “not applicable” for research faculty. Sixteen respondents (17%) stated a faculty member had failed to achieve promotion in the past 5 years because of poor teaching evaluations. Positive teaching evaluations outweighed low publication numbers for clinical faculty 24% of the time, compared with 5% for research faculty and 8% for tenured faculty being considered for promotion. The most common reason for rejection for promotion in all tracks was the number of publications. Awards for excellence in teaching improved chances of promotion.

Conclusions

Teaching quality is becoming more important in academic obstetrics-gynecology departments, especially for clinical faculty. Although in most institutions promotion is not achieved without adequate research and publications, the importance of teaching excellence is obvious, with 1 of 6 (17%) departments reporting a promotion had been denied due to poor teaching evaluations.

What was known

Academic promotions for clinical track faculty should assess and reward teaching contributions.

What is new

A survey of obstetrics-gynecology department chairs found that positive teaching evaluations aided promotions, while negative evaluations delayed promotions, particularly for clinical track faculty.

Limitations

A 50% response rate, with lower rates for key subquestions; the survey did not target promotions committees as the most relevant respondent group.

Bottom line

One in 6 department chairs reported that negative teaching evaluations resulted in delay of or denied promotion for a faculty member in the past 5 years.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument (36KB, doc) used in this study.

Introduction

Promotion of faculty in academia is dependent on a number of factors, including scope of research, number of publications, national leadership recognition, and quality of teaching.1 In 1990, Boyer2 asserted that teaching can and should be treated as scholarly work. In the most recent edition of “A Guide for Designing Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology,”3 the Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology (CREOG) stated that “vital to the development of a successful residency program is an enthusiastic and actively involved teaching faculty.” Teaching excellence traditionally has been less critical for promotion than research and publishing,4 and faculty focused on clinical care and teaching have been promoted at a slower pace than their research colleagues.4 Recently the value placed on teaching in residency programs has increased,5 and the retention of excellent educators seems to have become increasingly important to medical education and academic departments.6 Multiple studies have examined promotion of faculty as educators, but often this research is focused on the scholarship of education and not on teaching quality, as shown by resident evaluations. No obstetrics-gynecology study has analyzed the influence of resident evaluations on the promotion of faculty.

Our descriptive study aimed to explore how resident evaluations of faculty teaching affect faculty promotion.

Methods

We developed a 28-item questionnaire (provided as online supplemental material) and distributed it electronically to all department chairs of US obstetrics-gynecology residency programs. The survey was designed and developed, pilot-tested with select chairs, and revised. Questions focused on the following key issues: departmental demographics, characteristics of faculty, faculty tracks, faculty evaluation and feedback, positive and negative effects of feedback on promotion, importance of teaching awards, and resources offered for teaching improvement. As chairs are responsible for submitting faculty applications for promotion, they are uniquely qualified to assess the impact of teaching activities and skills on the promotion of their faculty. Department chair names and contact information were accessed via the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) website.7 Individual responses were gathered anonymously for analysis, tracking only the number of surveys sent and the number of responses received. Two weeks after the survey was initially sent via e-mail, a reminder e-mail was distributed. For the primary outcome, respondents were asked to consider the relationship between faculty promotion and resident evaluation. Data were reported in overall numbers and percentages. For analysis purposes, the clinical track included data from clinical scientists, clinical educators, and other clinician tracks because the answers to each of these tracks were nearly identical, and therefore, there was no need to separate them into these categories.

Not all numbers added up to 100% because not all chairs answered all questions.

The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Respondent Demographics

Our response rate was 50% (93 of 185). The majority (93%) of respondents were non-Hispanic White between the ages of 56 and 60, and their median tenure as chair was 7 years, with a range of 1 to 28 years. Seventy-seven percent of chairs were men and 23% were women. Eighty percent of respondents (74 of 93) chaired a university-based department, and 14 were in community-based departments.

The number of faculty in responding departments ranged from 1 to 250, with most having fewer than 60. The majority of chairs (69) had at least 75% of faculty teaching residents, with only 3% (3 chairs) of programs having less than half of faculty involved in resident teaching.

Promotion of Faculty

Most department chairs reported having all categories of faculty in their departments, including tenured faculty, clinical faculty (clinical educators, clinical scientists, other clinicians), research faculty, and other faculty. On average, over the past 5 years, 29% of chairs promoted 0 to 1 faculty member per year, 17% promoted 1 to 2 faculty members per year, 6% promoted 2 to 3 faculty per year, and 22% promoted more than 3 faculty members per year. Eight percent answered that this question was not applicable.

Residents' Evaluations of Faculty and Promotion

Residents evaluated faculty yearly in 29%, biannually in 28%, quarterly in 15%, and monthly in 12% of the departments polled. One department responded that faculty members are never evaluated by residents. Most evaluations were written only, including online (55%), while a minority (9%) of programs provided faculty with verbal reports only. Twenty-five percent of departments provided faculty with both verbal and written reports. Thirty-eight of 77 chairs (49%) always personally reviewed the resident evaluations with faculty, 17 (18%) most of the time, 7 (8%) approximately half of the time, 12 (13%) rarely, and 3 (3%) never did so. For those chairs who did not personally review resident evaluations with teaching faculty, 45% stated that the program director performed that task, and 20% stated the division director did. In the case of poor evaluations, 62% of chairs answered that assistance was always given, while 12% answered that it was given most of the time, and 1% responded assistance was given occasionally.

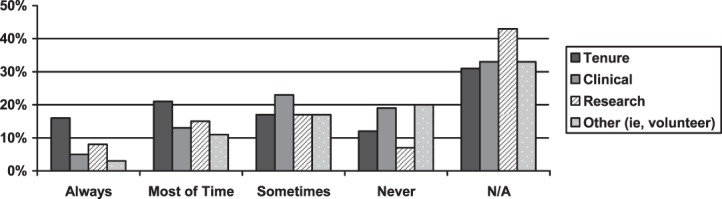

Results from the question, “If a faculty [member] has strong research and publication portfolio, does this help counteract any poor teaching evaluations?” show that poor teaching evaluations have a greater negative impact for clinical track faculty (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Responses To Survey Questiona “If a Faculty [Member] Has Strong Research and Publication Portfolio, Does This Help Counteract Any Poor Teaching Evaluations?”

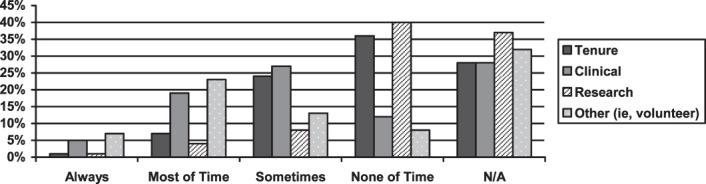

Responses to the question, “Do positive resident teaching evaluations of faculty outweigh low publication numbers and allow faculty to be promoted to the next academic level?” show that for clinical faculty, positive teaching evaluations may outweigh low publication numbers (figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Responses To Survey Questiona “Do Positive Resident Teaching Evaluations of Faculty Outweigh Low Publication Numbers and Allow Faculty to be Promoted to the Next Academic Level?”

Weight of Resident Evaluations

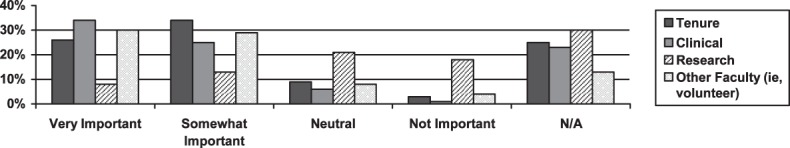

figure 3 shows results of responses to the question, “When considering promotion of teaching faculty, how important are resident evaluations?” This showed that resident evaluations were most important for promotions for clinical track faculty.

FIGURE 3.

Responses To Survey Questiona “When Considering Promotion of Teaching Faculty, How Important are Resident Evaluations?”

Our survey found that for each track, most faculty promotions had been accepted. However, 8% of department chairs answered that faculty had been rejected for promotion in the clinical tracks, 7% in other faculty and tenure tracks, and 2% in the research track. Seventeen percent of responding chairs reported that in the past 5 years, a member of their faculty had failed to achieve promotion due to poor teaching evaluations. Of chairs who reported cases of failed promotion, common responses included providing counseling and/or coaching and encouraging individuals who did not achieve promotion to attend faculty development courses.

When asked about the importance of teaching evaluations in the last 10 years, 40% of respondents replied that resident evaluations have become more important and 39% said the importance of resident evaluations have remained the same. Most chairs who completed the survey stated that lack of adequate numbers of teaching evaluations by residents is not an issue (84%), while 16% said it has been a problem.

Teaching Awards

Seventy-four percent of departments polled recognize faculty's teaching contributions at least annually by giving out a special educator award; 76% of respondents' institutions have special excellence in education awards; and 77% annually submit faculty names for APGO/CREOG teaching awards. Thirty-seven percent answered that most of the time, excellence in teaching awards increase the chances of promotion of faculty, with 17% reporting that it always does, 10% that it does so about half of the time, 13% indicating rarely, and 3% indicating never.

Positive teaching evaluations outweigh low publication rates (most of the time or always) 24% for the clinical track and 8% for the tenure track. Teaching evaluations were deemed “very important” 34% of the time for clinical track when considering faculty for promotion, whereas teaching evaluations were more likely to be rated “not important” or “not applicable” for research track faculty.

When queried about whether resident evaluations of faculty have become more important in the promotion of faculty in the last 10 years, 50% of those who answered replied “more important” and 50% replied “about the same.” Excellence in teaching awards improved the chances of promotion according to most chairs. The most common reason for rejection of faculty promotion in all tracks was number of publications.

Of the departments polled, 47% of faculty maintained an education portfolio, whereas 32% did not. In 56% of the departments that did maintain education portfolios, the department chairs reported providing guidance on how to maintain or develop faculty education portfolios, and 14% reported that they did not provide this guidance.

Discussion

In our study, positive teaching evaluations outweigh low publication rates for the clinical track compared to the tenure track faculty, showing there is a trend to make good teaching itself more important. Chairs consider teaching evaluations important when considering clinical faculty for promotion but not important when considering research faculty for promotion. This was shown by the fact that 1 of 6 responding chairs (17%) reported that in the past 5 years, a faculty member had failed to achieve promotion because of poor teaching evaluations. Positive teaching evaluations outweigh low publication numbers for clinical faculty 24% of the time compared with 5% for research faculty and 8% for tenured faculty, when being considered for promotion. Additionally, excellence in teaching awards improves the chances of promotion according to the most chairs. For all tracks, however, promotion of faculty is still largely dependent on research and publications according to the chairs surveyed in this study. Although evidence of excellent teaching helps and all faculty must publish somewhat, it appears that good teachers can be promoted in a more asymmetrical way (better teaching, less publication) if their teaching is very strong. Data from this survey of chairs of obstetrics-gynecology departments show that resident evaluations appear to have a greater impact on promotion of clinical faculty than those on the instructional and research tracks, with negative evaluations delaying promotion, while positive resident evaluations help promote faculty. For faculty on the tenure and research tracks, teaching is clearly not as important as research and publishing. Chairs of academic departments can use these data to demonstrate the potential rewards for the faculty member whose strength is teaching by helping faculty document their excellence in teaching and teaching awards.

Rewarding teaching excellence appears to be an important factor in retention of good faculty.8 Also, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education's annual resident survey places a high value on resident education. The focus on outcomes in the Next Accreditation System, set to begin for obstetrics-gynecology in July 2014, will contribute to the growing importance of resident evaluations of faculty teaching.9

Other studies have looked at the effect of teaching on promotion of faculty. Huggett et al10 found that teaching awards advanced faculty careers. Arah et al11 used a competency-based faculty evaluation tool that discriminated between effective and ineffective teachers, which has implications for promotion.

Academic promotion is important to faculty for a variety of reasons, including academic status; compensation; recognition in the department, institution, and among regional and national peers; and personal satisfaction.12,13 Retaining excellent teachers in academic medicine is as vital as understanding what motivates faculty to remain in academic practice.3,14 Most institutions have a clinical track as well as the more traditional tenure and research tracks, and our findings show that teaching plays an important role in promotion for this group of obstetrics-gynecology faculty.

Limitations of our study include the length of the survey and the complexity of some of the questions. These may have affected results as some chairs did not complete or answered “N/A [not applicable]” on many questions. Ideally, we should have surveyed academic promotion and tenure committees, but our research team felt this would be difficult to achieve given the composition of such committees (ie, a large number of participants from a variety of different departments and the challenge of identifying the appropriate individuals and the likelihood of a poor response rate).

Conclusion

Teaching is becoming more important in academic obstetrics-gynecology departments, especially for individuals in clinically oriented tracks. Although promotion of faculty in most institutions cannot be achieved without adequate publications, the importance of teaching excellence is obvious as 1 of 6 (17%) departments in this study in the past 5 years denied a promotion due to poor teaching evaluations.

Footnotes

All authors are in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan Health System. Diana S. Curran, MD, is Assistant Professor and Residency Program Director; Caren M. Stalburg, MD, MA, is Assistant Professor; Xiao Xu, PhD, is Research Assistant Professor; Samantha R. Dewald, BS, is Research Assistant; and Elisabeth H. Quint, MD, is Professor and Assistant Dean.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Presented as a poster at the Council for Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology and Association of Processors of Gynecology and Obstetrics Annual Meeting, March 9–12, 2011, San Antonio, TX

References

- 1.Simpson D, Fincher RM, Hafler JP, Irby DM, Richards BF, Rosenfeld GC, et al. Advancing educators and education by defining the components and evidence associated with educational scholarship. Med Educ. 2007;41(10):1002–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyer EL. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RP, Nugent CE, Bienstock JL, Edelman A, Ginsburg FW, Lapeyre ER, et al. A Guide for Designing Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 4th ed. 2009:8. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levinson W, Rothman AI, Philipson E. Creative professional activity: an additional platform for promotion of faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(6):568–570. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000225223.45701.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feder ME, Madara JL. Evidence-based appointment and promotion of academic faculty at the University of Chicago. Acad Med. 2008;83(1):85–95. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815c64d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pessar LF, Levine RE, Bernstein CA, Cabaniss DS, Dickstein LJ, Graff SV, et al. Recruiting and rewarding faculty for medical student teaching. Acad Psychiatry. 2006;30(2):126–129. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.30.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association of Professors in Gynecology and Obstetrics. Resident directory search. http://www.apgo.org/component/residencedirectory. Accessed August 28, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox SS, Swanson MS. Identification of teaching excellence in operating room and clinic settings. Am J Surg. 2002;183(3):251–255. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00787-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huggett KN, Greenberg RB, Rao D, Richards B, Chauvin SW, Fulton TB, et al. The design and utility of institutional teaching awards: a literature review. Med Teach. 2012;34(11):907–919. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.731102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arah OA, Hoekstra JB, Bos AP, Lombarts KM. New tools for systematic evaluation of teaching qualities of medical faculty: results of an ongoing multi-center study. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlstrom J, Dorai-Raj A, McGill D, Owen C, Tymms K, Watson DA. What motivates senior clinicians to teach medical students. BMC Med Educ. 5:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morahan PS, Fleetwood J. The double helix of activity and scholarship: building a medical education career with limited resources. Med Educ. 2008;42(1):34–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowenstein SR, Fernandez G, Crane LA. Medical school faculty discontent: prevalence of predictors of intent to leave academic careers. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]