Abstract

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a major chronic neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a hyperdopaminergic state. The hypoadenosinergic hypothesis proposes that reduced extracellular adenosine levels contribute to dopamine D2 receptor hyperactivity. ATP, through the action of ecto-nucleotidases, constitutes a main source of extracellular adenosine. In the present study, we examined the activity of ecto-nucleotidases (NTPDases, ecto-5′-nucleotidase, and alkaline phosphatase) in the postmortem putamen of SZ patients (n = 13) compared with aged-matched controls (n = 10). We firstly demonstrated, by means of artificial postmortem delay experiments, that ecto-nucleotidase activity in human brains was stable up to 24 h, indicating the reliability of this tissue for these enzyme determinations. Remarkably, NTPDase-attributable activity (both ATPase and ADPase) was found to be reduced in SZ patients, while ecto-5′-nucleotidase and alkaline phosphatase activity remained unchanged. In the present study, we also describe the localization of these ecto-enzymes in human putamen control samples, showing differential expression in blood vessels, neurons, and glial cells. In conclusion, reduced striatal NTPDase activity may contribute to the pathophysiology of SZ, and it represents a potential mechanism of adenosine signalling impairment in this illness.

Keywords: Ecto-nucleotidases, Adenosine, CD39, CD73, Schizophrenia, Postmortem

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a mental disorder with a global prevalence of 1 %. It is characterized by positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms. Its origin is unknown, although positive symptoms are related to hyperdopaminergic activity of the dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) [1]. Negative and cognitive symptoms are attributed to reduced glutamatergic activity via N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR), which in turn potentiates dopamine release. Indeed, the activation of D2Rs with amphetamines, as well as the use of NMDAR blockers, promotes pschycotic-like behavior in healthy people [2, 3]. Therefore, the normalization of the dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems is a pharmacological goal for the outcome of this neurological disorder. Regarding this, adenosine modulates dopaminergic and glutamatergic signalling pathways and is, therefore, a candidate target in the treatment of SZ [4].

Adenosine is a nucleoside widely distributed in the organism with neuromodulative and neuroprotective activity in the central nervous system. It presents four specific G-protein-coupled receptors (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) [5]. A1Rs and A2AR are the most expressed receptors in the brain. The modulation of A1Rs inhibits presynaptic glutamate release, while postsynaptic A2AR activation can promote dopamine D2 receptor signalling inhibition through the heterodimer A2AR–D2R formation [6, 7]. Interestingly, a hypoadenosinergic state has been proposed in SZ [8]. Therefore it is conceivable that the mechanisms regulating extracellular adenosine levels are impaired. In line with this, increased serum adenosine deaminase (ADA) activity, which converts extracellular adenosine into inosine, as well as low frequency of the low activity ADA allelic variant, has been reported in SZ patients [9, 10]. Moreover, transgenic mice overexpressing adenosine kinase, a cytosolic ribokinase that phosphorylates the re-uptaken adenosine into 5′-adenosine monophosphate (AMP), show attention impairments linked to SZ, while adenosine augmentation exerts antipsychotic-like activity in mice [11]. In fact, several clinical trials have shown the beneficial effects of drugs that modulate adenosine signalling such as allopurinol and dipyridamole, which increase extracellular adenosine levels by inhibiting its degradation and reuptake, respectively [12–17]. Interestingly, caffeine (a non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist) consumption exacerbates psychotic symptoms in SZ patients [18]. All these data support the “adenosine hypothesis” in SZ, and it has been proposed the use of A2AR agonists in combination with antipsychotics, in order to potentiate their inhibitory role over D2Rs [19].

Although adenosine can be directly released via specialized nucleoside transporters [20], the main source of extracellular adenosine is the hydrolysis of 5′-adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through ecto-nucleotidases [21]. This includes different families of nucleotide-hydrolyzing enzymes expressed at the cell surface that, alone or acting sequentially, generate adenosine from adenine nucleotides (i.e., ATP, ADP, or AMP): (a) the ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (E-NTPDase) family includes four plasma membrane-bound members: NTPDase1 (CD39), NTPDase2, NTPDase3, and NTPDase8; these enzymes are differentially expressed and hydrolyze nucleoside triphosphates and diphosphates to their monophosphate derivatives; (b) the ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (E-NPP) family has three members (NPP1-3) capable of hydrolyzing nucleoside triphosphates to monophosphates and PPi, such as ATP to AMP and PPi; (c) the 5′-nucleotidase family has several intracellular members but only one member is attached to the plasma membrane with an extracellularly located active site, the ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73), a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-linked membrane-bound glycoprotein that efficiently hydrolyzes AMP to adenosine; and (d) the alkaline phosphatase (AP) family includes ubiquitous enzymes, such as the tissue nonspecific AP (TNAP), with broad substrate specificity, including adenine nucleotides and pyrophosphate, releasing inorganic phosphate. The distribution of ecto-nucleotidases in brain has been studied in rodents [22], but little is known of their distribution in humans. The main goal of this study was to characterize ecto-nucleotidase activity in brains of SZ patients and controls, in order to determine whether these enzymes may also be considered as potential contributors to the hypoadenosinergia reported in SZ.

Materials and methods

Human brain samples

The putamen samples from SZ patients used in this study were provided by the Sant Joan de Déu Brain Bank (Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain), and the control samples were obtained from the Brain Bank of the Institute of Neuropathology (HUB-ICO-IDIBELL Brain Bank, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain). The donation and obtaining of samples were regulated by the ethics committee of both institutions. The sample processing followed the rules of the European Consortium of Nervous Tissues: BrainNet Europe II (BNEII). All the samples were protected in terms of individual donor identification following the BNEII laws. Clinical diagnosis of SZ in donor subjects was confirmed premortem with DMS-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th edition) and ICD-10 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) criteria by clinical examiners. Most donors were hospitalized for more than 40 years and were re-evaluated every 2 years to monitor and update their clinical progression. Anatomic pathology exploration of all SZ samples was performed at the Hospital of Bellvitge to identify the degree of certain histopathological alterations, as described (Table 1). The neuropathological diagnoses were made according to well-established criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [23]. None of the SZ cases showed sustantia nigra neurodegeneration.

Table 1.

Summary of the main clinical and neuropathological features of the human samples studied, and drug treatment administrated to each SZ patient

| Sample ID no. | Clinical manifestation | Postmortem analysis (AD Braak stages) | Gender | Age (years) | Postmortem delay | TAPs | AAPs | BZD | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control | I/A | M | 65 | 5 h 15 min | ||||

| 2 | Control | I/0 | M | 56 | 7 h 10 min | ||||

| 3 | Control | I/A | F | 64 | 2 h 15 min | ||||

| 4 | Control | II/A | M | 71 | 5 h 15 min | ||||

| 5 | Control | II/A | F | 86 | 4 h 15 min | ||||

| 6 | Control | III/A | F | 77 | 11 h 30 min | ||||

| 7 | Control | III/B | M | 85 | 4 h 45 min | ||||

| 8 | Control | III/A | F | 71 | 6 h 45 min | ||||

| 9 | Control | IV/C | F | 69 | 8 h 10 min | ||||

| 10 | Control | IV/C | F | 81 | 5 h | ||||

| 11 | Residual SZ | II/A | M | 74 | 7 h | √ | √ | Antidepressants and anticholinergics | |

| 12 | Paranoid SZ | II/0 | M | 69 | 8 h | √ | √ | √ | Anticholinergics |

| 13 | Residual SZ | II/0 | M | 87 | 3 h | √ | √ | √ | |

| 14 | Residual SZ | I/B | M | 76 | 5 h 15 min | √ | √ | ||

| 15 | Residual SZ | I/A | M | 89 | 1 h | ||||

| 16 | Residual SZ | II/A | M | 75 | 6 h | √ | √ | ||

| 17 | Residual SZ | III/A | M | 80 | 6 h | √ | √ | ||

| 18 | Disorganized SZ | III/0 | M | 78 | 7 h | √ | √ | ||

| 19 | Residual SZ | III/A | M | 90 | 3 h | √ | |||

| 20 | Residual SZ | IV/C | M | 80 | 4 h 50 min | √ | √ | √ | |

| 21 | Paranoid SZ | IV/0 | M | 81 | 5 h | √ | √ | √ | |

| 22 | Residual SZ | III/A | M | 76 | 8 h | √ | √ | √ | Anticholinergic and antiepileptic |

| 23 | Residual SZ | III/C | M | 92 | 2 h | √ | √ | Antidepressant and antiepileptic |

AD Braak stages indicates the stage of neurofibrillary tangles (Roman numerals) and senile plaques (letters) according to Braak and Braak [23]

M male, F female, AD Alzheimer’s disease, TAPs typical antipsychotics, AAPs atypical antipsychotics, BZD benzodiazepines

The left cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres and alternate sections of the brain stem were fixed in 4 % buffered formalin for 3 weeks. Selected samples were embedded in paraffin and processed for neuropathological study. The other half of the cerebrum and cerebellum was cut on coronal slices and, together with remaining alternate sections of the brain stem, was immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C. For histological studies, brain samples were fixed with 4 % buffered formalin, cryopreserved with 30 % sucrose, and stored at −80 °C.

Immunohistochemistry experiments

Immunohistochemistry experiments were performed as described previously [24] except for the use of 30-μm-thick free-floating slices. Slices were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following anti-human-monoclonal antibodies: CD39 (1:500; Ancell, Minnesota, USA), hN3-B3S for NTPDase3 (1:500; http://ectonucleotidases-ab.com/) and CD73 (1:50; Hycult biotechnology, Uden, The Netherlands). Tissue sections were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse (EnVisionTM + system, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA) as secondary antibody for 1 h at RT. Secondary antibody alone was routinely included as control for the immunohistochemistry experiments. Samples were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with Fluoromount aqueous mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were observed and photographed under a light Leica DMD 108 microscope.

In situ activity experiments

Histochemical localization of ATPase, ADPase, and AMPase activity was carried out using the Wachstein/Meisel lead phosphate method [24–26] in cryostat-obtained (30-μm thick) free-floating slices. Enzymatic reaction was measured for 30 min (ATPase assay) or for 1 h (ADPase and AMPase assays) at 37 °C in the presence of 2.5 mM levamisole, as an inhibitor of AP activity, and with 200 μM ATP, 1 mM ADP, or 1 mM AMP as a substrate. For NTPDase inhibition experiments, ATPase and ADPase reactions were carried out in the presence of 1 mM suramin (Sigma-Aldrich) or 1 mM NF279 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) [27]. For ecto-5′-nucleotidase inhibition experiments, AMPase reactions were performed in the presence of 1 mM α,β-methylene-ADP (α,β-meADP). The substrates were omitted in control experiments. The reactions were revealed by incubation with 1 % (NH4)2S v/v for exactly 1 min. Samples were mounted, observed, and photographed as described above.

In situ alkaline phosphatase activity experiments

The histochemical localization of AP was addressed by using the method of Gossrau with some modifications [24, 28]. Briefly, cryostat-obtained (30-μm thick) free-floating slices were washed twice in 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.4, containing 5 mM MgCl2, and then pre-incubated with the same buffer at pH 9.4 for 15 min at RT. Enzymatic reaction was started by adding 200 μl of revealing reagent BCIP®/NBT liquid substrate system (Sigma-Aldrich) for 7 min at RT, and stopped with 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.4. For AP inhibition experiments, 5 mM levamisole was added to both pre-incubation and enzymatic reaction buffers. In control experiments, the revealing reagent BCIP was omitted. Samples were mounted, observed, and photographed as described above.

Artificial postmortem delay

For this experiment, all the samples were obtained between 3.45 and 4.55 h after death (considered time 0 for the present purpose) and the brains were processed as previously indicated, except for a fresh fragment of the frontal cortex (area 8 of Brodmann) that was cut into small pieces, one of them immediately frozen (time 0) and the rest maintained at room temperature (20 °C) for 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h, and then frozen and stored at −80 °C. The cases analyzed are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the main clinical and neuropathological features of the samples used for the artificial postmortem delay

| Sample ID no. | Postmortem analysis | Gender | Age (years) | Postmortem delay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0767 | Control | M | 47 | 4 h 55 min |

| A0563 | AD V/B | M | 68 | 4 h 45 min |

| A0816 | AD III/A | M | 85 | 3 h 45 min |

M male, AD Alzheimer’s disease, indicating the Braak and Braak stages [23]

Plasma membranes isolation

Human brain putamen samples (50–100 mg) were used to isolate plasma membranes, as previously described [29].

NTPDase and ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity assays

NTPDase (ATPase, ADPase) and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (AMPase) activity was determined by measuring the amount of liberated inorganic phosphate (Pi) using a colorimetric assay. The incubation mixture contained 160 mM (Tris)–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM CaCl2, 5 mM levamisole, as alkaline phosphatase inhibitor, and 1 mM ATP, ADP, or AMP as substrates in a final volume of 150 μl. The assay was initiated by adding the membrane-enriched samples (1 μg for ATPase and ADPase assay and 10 μg for AMPase assay). After an incubation of 20 min at 37 °C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 22.5 μl of 34 % trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Incubation times and protein concentrations were chosen to ensure the linearity of the enzymatic reaction. The release of inorganic Pi was measured with the malachite green method [30]. KH2PO4 was used as a Pi standard. Controls to determine nonenzymatic Pi accumulation were performed by incubating either the membrane-enriched samples in the absence of the substrate, or the substrate alone. All samples were analyzed in triplicate. Enzyme activity was expressed as OD arbitrary units at 620 nm.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity assay

AP activity in membrane-enriched samples was determined as described previously [31]. Briefly, 20 μg of sample was assayed at room temperature in the following reaction mixture: 0.2 M diethanolamine buffer pH 9.8, (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA), 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate as substrate (pNPP) (Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence or absence of 5 mM levamisole. Reactions were stopped after 30 min with 0.1 M NaOH. AP activity was determined as the liberated p-nitrophenol and was measured at 405 nm. Controls in the presence of levamisole and in the absence of the substrate were performed. All samples were assayed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation, and the number of experiments and samples are indicated for each experiment. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test to compare group means since data fit to a normal distribution, with a p value <0.05.

Results

Localization of ecto-nucleotidase activity in control human brain samples

In situ histochemistry experiments in brain control samples revealed substantial ATPase and ADPase catalytic activity (Fig. 1a, c). ADPase activity was clearly localized to endothelial cells and microglia, largely coinciding with the NTPDase1 (CD39) distribution detected by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1d). ATPase activity coincided with ADPase localization and was also present in the gray matter of striatum, matching with the anti-NTPDase3 staining (Fig. 1b). ATPase and ADPase activity was inhibited by suramin (Fig. 1c) and NF279 (not shown), suggesting that the in situ activity detected was due to the action of NTPDases.

Fig. 1.

In situ enzyme activity (a, c, e, g, h) and immunolabeling (b, d, f) of ecto-nucleotidases in the putamen control samples. Activity shown is: ATPase (a), ADPase (c), AMPase (e), and alkaline phosphatase (g, h in the presence of the inhibitor levamisole). Inset in c shows the ADPase activity in the presence of the inhibitor suramin, and inset in e the AMPase activity in the presence of the inhibitor αβMeADP. Immunolabeling was performed for NTPDase3 (b), NTPDase1/CD39 (d), and ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73 (f). IC internal capsule, STR striatum. Arrows point to blood vessels, and black arrowheads to glial cells. Scale bars = 100 μm in a, b, e, f, g, h, and insets, and 50 μm in c and d

AMPase activity was present in the brain (Fig. 1e). The activity pattern obtained was, however, diffuse, and the precise localization of the ecto-enzyme was difficult to establish. The activity was attributable to ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) since the specific inhibitor α,β-meADP abrogated the signal. Using an anti-CD73 antibody, the enzyme was localized to glial cells and also to neuropil (Fig. 1f).

Alkaline phosphatase activity was intense in blood vessels (Fig. 1g). The activity was abrogated in the presence of the alkaline phosphatase inhibitor levamisole, confirming the specificity of the activity detected (Fig. 1h).

Ecto-nucleotidase activity in human brain along an artificial postmortem delay experiment

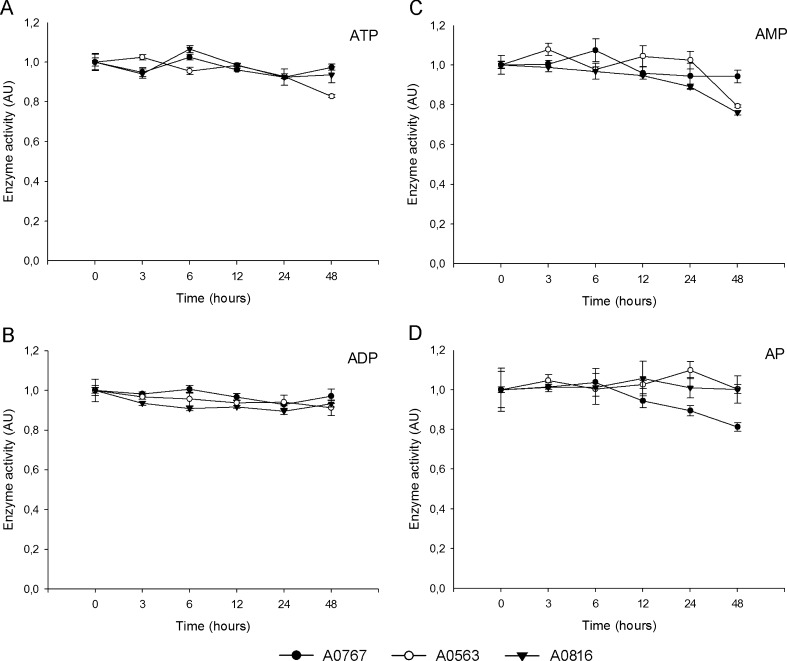

In order to characterize the behavior of ecto-nucleotidase activity in human postmortem brain homogenates, a progressive artificial postmortem delay was performed, since it is well known that some enzymatic activity is more vulnerable to postmortem delay than other. Our results, compiled in Fig. 2, showed that NTPDase activity (ADPase and ATPase) was very stable throughout the postmortem delay, and that ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity (AMPase) was more variable from the time point of 12 h with a tendency to decrease. AP activity was invariable until the time point of 12 h and then started to decrease and displayed more heterogeneity between samples.

Fig. 2.

Enzyme activity in artificial postmortem delay. Three different samples (A0767, black circles; A0563, white circles; A0816, black triangle) from the frontal cortex (area 8 of Brodmann) were analyzed (see the “Material and methods” section). Experiments were performed in triplicate and the graphs correspond to one representative experiment for each sample (n = 3). Means and standard deviations of ATPase (a), ADPase (b), AMPase (c), and alkaline phosphatase (d) activity are represented. Values are normalized and activity is represented in arbitrary units (AU)

Ecto-nucleotidase activity in human brains from SZ patients

Ecto-nucleotidase activity in putamen homogenates of SZ patients was compared with age-matched controls (Table 1). All SZ samples were from patients suffering this neurological disorder, although postmortem analysis also revealed the presence of several hallmarks (β-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) typical of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) at different Braak and Braak stages. For this reason, the control group used was from human cases with AD I–IV stages of Braak and Braak. However, as the activity of the four ecto-nucleotidases measured showed no significant differences among control samples (samples 1–10, Table 1; data not shown), we carried out the analysis comparing SZ cases (samples 11–23, Table 1) with respect to all control samples. Results obtained are shown in Fig. 3. A significant decrease in ATP and ADP hydrolysis (15 % and 12 %, respectively) was recorded in SZ samples (p = 0.012 and p < 0.001, respectively). No significant differences were found for ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity or alkaline phosphatase.

Fig. 3.

Enzyme activity in the putamen of schizophrenia (SZ) versus control samples. ATPase (a), ADPase (b), AMPase (c), and alkaline phosphatase (d) activity were determined. Experiments were performed in triplicate for each sample. Data are represented with boxplots in arbitrary units (AU). n = 13 for SZ and n = 10 for controls. Significant differences at ***p < 0.001 and at *p < 0.05

Discussion

Several lines of evidence indicate that hypofunction of adenosine signalling, linked to dopaminergic impairment, may contribute to the pathophysiology of SZ. It has recently been reported in mice that augmentation of adenosine ameliorates psychotic and cognitive symptoms linked to SZ [11]. In consequence, a detailed understanding of metabolic pathways involved in the control of extracellular adenosine levels in brain is needed to promote future therapies. The ATP released from brain cells is the main source of extracellular adenosine through the action of sequentially acting ecto-nucleotidases. The focus of our study was to determine ecto-nucleotidase activity in human brain samples of patients with SZ compared with age-matched controls.

Here we studied the expression of three different families of ecto-nucleotidases in the postmortem putamen of human control brains. We analyzed this cerebral region as some evidence points to the existence of striatal hyperdopaminergic activity secondary to hypofunction of the prefrontal dopamine system [32, 33], whereas D2R and A2AR are expressed mainly in medium-sized GABAergic spiny neurons [6]. Interestingly, a recent study showed that, in rodent, ecto-5′-nucleotidase is specifically expressed in this neuronal population, being responsible for most of the extracellular adenosine produced in the striatum [34]. Although the distribution of ecto-nucleotidases in the rodent brain has been deeply examined [22], little information was available on humans.

ATPase and ADPase activity was identified in striatal samples. The activity was attributable to NTPDases since they were abolished by the use of inhibitors. NTPDase1 (CD39) was immunodetected in microglia and blood vessels, coinciding with the localization of ATPase and ADPase activity and in agreement with the previous characterization of this enzyme in mice [35]. Another member of the NTPDase family, NTPDase3, was detected in striatal gray matter, where ATPase activity was also localized. Less ADPase activity was detected in this structure, reinforcing the idea that the above-mentioned ATPase activity in gray matter is attributable to NTPDase3, with a hydrolysis ratio of ATP:ADP of 5:1. The presence of NTPDase3 was already confirmed in rat brain by western blot [36]. In the present study we did not look at the other two membrane-associated members of the NTPDase family, NTPDase2, and NTPDase8. It is known that in rodents, NTPDase2 is expressed in neural stem cells in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles [37], and no ntpdase8 mRNA could be detected by PCR in mouse brain [38].

Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) was expressed and notably active in the putamen samples studied. Although the activity pattern was diffuse and difficult to assign to a particular structure, as already reported in other mammalian brains [22], the specificity of the reaction was proven by the use of α,β-meADP.

As expected, alkaline phosphatase activity was detected in blood vessels. This activity was intense and completely abrogated with the AP inhibitor levamisole. Previous reports have demonstrated that AP activity in human brain is attributable to TNAP expression [39, 40].

In summary, our results indicate that NTPDases and ecto-5′-nucleotidase are, in physiological extracellular pH, the dominant ecto-nucleotidases, as already reported in brains of other mammals [22]. These results support the role of both neurons and glial cells in the extracellular adenosine metabolism in brain.

The human postmortem brain is a very useful tissue to unravel the molecular pathways that play a role in human neurological diseases [41]. However, special care must be taken as there are several technical limitations for molecular studies, such as time after death and storage temperature [42]. For these reasons, we aimed to assess the effect of postmortem delay on ecto-nucleotidase activity. We demonstrated that ATPase and ADPase activity is stable throughout the artificial postmortem delay (i.e. for 48 h). A similar result was found for AMPase (CD73) activity, although in this case there is more variability at longer times and we suggest not exceeding 24 h postmortem in performing experiments involving this enzyme. In the case of AP activity, fluctuations were recorded after 12 h postmortem, pointing up the importance of studying samples obtained before this time after death. SZ and control samples used in this study were taken between 2 and 11.5 h after death (most of them before 8 h), at which time point activity was well preserved. In fact, these findings are not exclusive to ecto-nucleotidases, as the preservation of other enzymatic activity has been reported in this type of tissue [43–47]. The data presented here are of relevance for this and future study of ecto-nucleotidases in human brains.

In the present report, most of the samples, both SZ and control cases, showed an AD-related pathology, which was asymptomatic. This postmortem finding is consistent with previously reported postmortem analyses showing that 70–80 % of individuals over 65 years of age present AD-related pathology at the neuropathological level, but most of them have not developed AD [48]. Therefore, we performed a comparative study at the neuropathological level, but the final results may be considered as control vs SZ patients from a clinical point of view.

Although ecto-nucleotidases, and TNAP in particular, have been studied in Alzheimer disease [31, 49], no data were available on human ecto-nucleotidase expression in mental disorders such as SZ. By analyzing brain membranes, we have shown that NTPDase activity (both ATPase and ADPase) is significantly reduced in the putamen of SZ patients when compared with control samples. Although no significant changes were detected for either ecto-5′-nucleotidase or AP activity, a decrease in their available substrate, AMP, might contribute to the hypothesized adenosine reduction in SZ brains. Involvement of ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity in the adenosine levels of striatum has already been described in rats [50].

It is important to note the conditions of the tissues presented in this study. SZ patients underwent long-term drug treatment. Seibt et al. [51] have studied the effect of the antipsychotic drugs haloperidol, olanzapine and sulpiride, prescribed for SZ, on the nucleotide hydrolysis in brain membranes of zebrafish. They found decreased ADPase activity in the presence of haloperidol and sulpiride but only at the highest concentration tested (250 μM). No changes in ADPase activity were reported for olanzapine. Although we cannot rule out a putative effect of sustained drug treatment on enzyme activity in the cohort studied (except for patient #15, see Table 1), the effective drug concentration in the study of Seibt et al. exceeded the concentration of the drug in the blood of our SZ patients by over 3 log of magnitude. Considering the advisability of drug prescription in most of the diagnosed SZ patients, performing the present study in drug-naive patients would hardly be feasible. Another aspect to be considered is that all patients included in the present study were male since the postmortem brain collection of the Brain Bank belongs to a hospital formerly devoted to the care of male mental patients. Therefore, the study of a larger cohort should be considered.

In summary, in the present report we describe: (a) the distribution of ecto-nucleotidases in the putamen of human brains, (b) the preservation of the activity of four ecto-nucleotidases in human postmortem brains, and (c) the reduction in ecto-nucleotidase activity in the putamen of SZ patients. These findings reinforce the “adenosine hypothesis” in SZ and point to the modulation of ecto-nucleotidases as new potential targets in the treatment of this neurological disorder.

Acknowledgments

We thank Inmaculada Gómez de Aranda and Centres Científics i Tecnològics, Universitat de Barcelona, Campus de Bellvitge, Barcelona, Spain, for their technical assistance. We thank T. Yohannan for editorial assistance. There is no conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations. This study was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Instituto de Salud Carlos III [PI10/00305 to M.M.S.], and La Fundació La Marató de TV3 [090330 to M.B.]. I.V.M. is the recipient of an IDIBELL predoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

Mireia Martín-Satué and Marta Barrachina contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Mireia Martín-Satué, Phone: +34-93-4024279, FAX: +34-93-4035810, Email: martinsatue@ub.edu.

Marta Barrachina, Phone: +34-93-2607215, FAX: +34-93-2607215, Email: mbarrachina@idibell.cat.

References

- 1.Ross CA, Margolis RL, Reading SA, Pletnikov M, Coyle JT. Neurobiology of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2006;52:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kegeles LS, Zea-Ponce Y, Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Wang T, Weiss R, Van Heertum RL, Mann JJ, Laruelle M. Stability of [123I]IBZM SPECT measurement of amphetamine-induced striatal dopamine release in humans. Synapse. 1999;31:302–308. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990315)31:4<302::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, Heninger GR, Bowers MB, Jr, Charney DS. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boison D, Singer P, Shen HY, Feldon J, Yee BK. Adenosine hypothesis of schizophrenia-opportunities for pharmacotherapy. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1527–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredholm BB, Ijzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferré S, von Euler G, Johansson B, Fredholm BB, Fuxe K. Stimulation of high-affinity adenosine A2 receptors decreases the affinity of dopamine D2 receptors in rat striatal membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7238–7241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferré S. Adenosine-dopamine interactions in the ventral striatum. Implications for the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;133:107–120. doi: 10.1007/s002130050380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lara DR, Souza DO. Schizophrenia: a purinergic hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 2000;54:157–166. doi: 10.1054/mehy.1999.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunstein MG, Silveira EM, Jr, Chaves LS, Machado H, Schenkel O, Belmonte-de-Abreu P, Souza DO, Lara DR. Increased serum adenosine deaminase activity in schizophrenic receiving antipsychotic treatment. Neurosci Lett. 2007;414:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutra GP, Ottoni GL, Lara DR, Bogo MR. Lower frequency of the low activity adenosine deaminase allelic variant (ADA1*2) in schizophrenic patients. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32:275–278. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462010005000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen HY, Singer P, Lytle N, Wei CJ, Lan JQ, Williams-Karnesky RL, Chen JF, Yee BK, Boison D. Adenosine augmentation ameliorates psychotic and cognitive endophenotypes of schizophrenia. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2567–2577. doi: 10.1172/JCI62378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhondzadeh S, Shasavand E, Jamilian H, Shabestari O, Kamalipour A. Dipyridamole in the treatment of schizophrenia: adenosine-dopamine receptor interactions. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25:131–137. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2000.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhondzadeh S, Safarcherati A, Amini H. Beneficial antipsychotic effects of allopurinol as add-on therapy for schizophrenia: a double blind, randomized and placebo controlled trial. Progr Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunstein MG, Ghisolfi ES, Ramos FL, Lara DR. A clinical trial of adjuvant allopurinol therapy for moderately refractory schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:213–219. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickerson FB, Stallings CR, Origoni AE, Sullens A, Khushalani S, Sandson N, Yolken RH. A double-blind trial of adjunctive allopurinol for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lara DR, Brunstein MG, Ghisolfi ES, Lobato MI, Belmonte-de-Abreu P, Souza DO. Allopurinol augmentation for poorly responsive schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:235–237. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wonodi I, Gopinath HV, Liu J, Adami H, Hong LE, Allen-Emerson R, McMahon RP, Thaker GK. Dipyridamole monotherapy in schizophrenia: pilot of a novel treatment approach by modulation of purinergic signaling. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:341–345. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucas PB, Pickar D, Kelsoe J, Rapaport M, Pato C, Hommer D. Effects of the acute administration of caffeine in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;28:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dixon DA, Fenix LA, Kim DM, Raffa RB. Indirect modulation of dopamine D2 receptors as potential pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia: I. Adenosine agonists. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:480–488. doi: 10.1345/aph.18215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkinson FE, Damaraju VL, Graham K, Yao SY, Baldwin SA, Cass CE, Young JD. Molecular biology of nucleoside transporters and their distributions and functions in the brain. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:948–972. doi: 10.2174/156802611795347582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Strater N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer D, Hammer K, Koszalka P, Schrader J, Robson S, Zimmermann H. Distribution of ectonucleotidases in the rodent brain revisited. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;334:199–217. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0681-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braak H, Braak E. Temporal sequence of Alzheimer’s disease related pathology. In: Peters A, Morrison JH, editors. Cerebral Cortex. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. pp. 475–512. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aliagas E, Vidal A, Torrejón-Escribano B, Taco MD, Ponce J, Gómez de Aranda I, Sévigny J, Condom E, Martín-Satué M (2013) Ecto-nucleotidases distribution in human cyclic and postmenopausic endometrium. Purinergic Signal 9(2):227–37. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9345-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Aliagas E, Torrejón-Escribano B, Lavoie EG, de Aranda IG, Sévigny J, Solsona C, Martín-Satué M. Changes in expression and activity levels of ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73 along the mouse female estrous cycle. Acta Physiol (Oxford) 2010;199:191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wachstein M, Meisel E, Niedzwiedz A. Histochemical demonstration of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase with the lead-adenosine triphosphate technique. J Histochem Cytochem. 1960;8:387–388. doi: 10.1177/8.5.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munkonda MN, Kauffenstein G, Kukulski F, Lévesque SA, Legendre C, Pelletier J, Lavoie EG, Lecka J, Sévigny J. Inhibition of human and mouse plasma membrane bound NTPDases by P2 receptor antagonists. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1524–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schelstraete K, Deman J, Vermeulen FL, Strijckmans K, Vandecasteele C, Slegers G, De Schryver A. Kinetics of 13N-ammonia incorporation in human tumours. Nucl Med Commun. 1985;6:461–470. doi: 10.1097/00006231-198508000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Buira S, Barrachina M, Rodriguez A, Albasanz JL, Martín M, Ferrer I. Expression levels of adenosine receptors in hippocampus and frontal cortex in argyrophilic grain disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;423:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanzetta PA, Alvarez LJ, Reinach PS, Candia OA. An improved assay for nanomole amounts of inorganic phosphate. Anal Biochem. 1979;100:95–97. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Díaz-Hernández M, Gómez-Ramos A, Rubio A, Gómez-Villafuertes R, Naranjo JR, Miras-Portugal MT, Avila J. Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase promotes the neurotoxicity effect of extracellular tau. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32539–32548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson EH, Kellendonk C, Kandel E. A possible role for the striatum in the pathogenesis of the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2010;65:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:660–669. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ena SL, De Backer JF, Schiffmann SN, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A. FACS array profiling identifies ecto-5′ nucleotidase as a striatopallidal neuron-specific gene involved in striatal-dependent learning. J Neurosci. 2013;33:8794–8809. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2989-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun N, Sévigny J, Robson SC, Enjyoji K, Guckelberger O, Hammer K, Di Virgilio F, Zimmermann H. Assignment of ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1/cd39 expression to microglia and vasculature of the brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4357–4466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vorhoff T, Zimmermann H, Pelletier J, Sévigny J, Braun N. Cloning and characterization of the ecto-nucleotidase NTPDase3 from rat brain: Predicted secondary structure and relation to other members of the E-NTPDase family and actin. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:259–270. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6314-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun N, Sévigny J, Mishra SK, Robson SC, Barth SW, Gerstberger R, Hammer K, Zimmermann H. Expression of the ecto-ATPase NTPDase2 in the germinal zones of the developing and adult rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1355–1364. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bigonnesse F, Lévesque SA, Kukulski F, Lecka J, Robson SC, Fernandes MJ, Sévigny J. Cloning and characterization of mouse nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-8. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5511–5519. doi: 10.1021/bi0362222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brun-Heath I, Ermonval M, Chabrol E, Xiao J, Palkovits M, Lyck R, Miller F, Couraud PO, Mornet E, Fonta C. Differential expression of the bone and the liver tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase isoforms in brain tissues. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:521–536. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Négyessy L, Xiao J, Kántor O, Kovács GG, Palkovits M, Dóczi TP, Renaud L, Baksa G, Glasz T, Ashaber M, Barone P, Fonta C. Layer-specific activity of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase in the human neocortex. Neuroscience. 2011;172:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kretzschmar H. Brain banking: opportunities, challenges and meaning for the future. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:70–78. doi: 10.1038/nrn2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrer I, Martinez A, Boluda S, Parchi P, Barrachina M. Brain banks: benefits, limitations and cautions concerning the use of post-mortem brain tissue for molecular studies. Cell Tissue Bank. 2008;9:181–194. doi: 10.1007/s10561-008-9077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albasanz JL, Dalfó E, Ferrer I, Martín M. Impaired metabotropic glutamate receptor/phospholipase C signaling pathway in the cerebral cortex in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies correlates with stage of Alzheimer’s-disease-related changes. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:685–693. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albasanz JL, Rodríguez A, Ferrer I, Martín M. Adenosine A2A receptors are up-regulated in Pick’s disease frontal cortex. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.00026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monoranu CM, Grünblatt E, Bartl J, Meyer A, Apfelbacher M, Keller D, Michel TM, Al-Saraj S, Schmitt A, Falkai P, Roggendorf W, Deckert J, Ferrer I, Riederer P. Methyl- and acetyltransferases are stable epigenetic markers postmortem. Cell Tissue Bank. 2011;12:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s10561-010-9199-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puig B, Viñals F, Ferrer I. Active stress kinase p38 enhances and perpetuates abnormal tau phosphorylation and deposition in Pick’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;107:185–189. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0793-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodríguez A, Martín M, Albasanz JL, Barrachina M, Espinosa JC, Torres JM, Ferrer I. Adenosine A1 receptor protein levels and activity is increased in the cerebral cortex in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and in bovine spongiform encephalopathy-infected bovine-PrP mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:964–975. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000235120.59935.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrer I. Defining Alzheimer as a common age-related neurodegenerative process not inevitably leading to dementia. Progr Neurobiol. 2012;97:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vardy ER, Kellett KA, Cocklin SL, Hooper NM. Alkaline phosphatase is increased in both brain and plasma in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;9:31–37. doi: 10.1159/000329722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delaney SM, Geiger JD. Levels of endogenous adenosine in rat striatum. II. Regulation of basal and N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced levels by inhibitors of adenosine transport and metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:568–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seibt KJ, Oliveira Rda L, Rico EP, Dias RD, Bogo MR, Bonan CD. Antipsychotic drugs inhibit nucleotide hydrolysis in zebrafish (Danio rerio) brain membranes. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]