Abstract

This article explores how incarceration amplifies the disconnection from school and work experienced by urban, young men of color in the United States and ultimately leads to their social exclusion. The authors draw on longitudinal data collected in interviews with 397 men age 16 to 18 in a New York City jail and then again one year after their release. Using logistic regression analysis, the authors found that though incarceration did not appear to exacerbate disconnectedness directly, it was associated with unstable housing, which in turn may contribute to several negative outcomes related to social exclusion. These findings may inform advocates, policy makers, and researchers in their efforts to meet the needs of socially excluded youth, in particular those with criminal justice histories.

Keywords: social exclusion, incarceration, young men

INTRODUCTION

In the last two decades, the United States has relied heavily on incarceration as a social response to a variety of social problems, including drug use, crime, violence, and mental illness (Clear, 2007). As a result, millions of people, especially young Black and Latino men, have spent time or will spend time in jail or prison. Nationally, about 70% of inmates are Black or Latino (Wacquant, 2001). Blacks are 6 times as likely as Whites to be incarcerated, and Latinos are 2 times as likely Whites (Hartney & Vuong, 2009). Eight hundred thousand people younger than age 20 have spent time in the criminal justice system in the United States, the highest rate of youth incarcerated in the developed world (Harrison & Beck, 2006). In New York City, young men of color make up 95% of all inmates.

In this article, we explore the social consequences of this policy of mass incarceration, with a specific focus on how the intersection of economic trends, gender, and race or ethnicity precipitates the disconnection of low-income, urban, young men of color from education and employment. We explore how public policies often exclude young men of color from attending school and finding work, thus leaving them vulnerable to conditions that lead to arrest and incarceration. Finally, we describe how postincarceration policies and trends solidify this separation, leading to deeper social exclusion.

To assess the unique ways that incarceration enhances the disconnection associated with poverty, race, and gender, we present a conceptual framework for the relationship between disconnection, incarceration, and social exclusion. We then use this framework to describe and analyze the school, work, criminal justice, housing, and health care experiences of a group of 397 young men, age 16 to 18, recruited and interviewed while in jail and then interviewed again one year after their release from jail.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

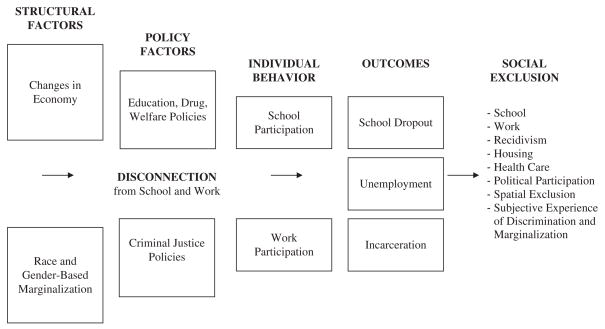

To analyze the social processes that link incarceration to social exclusion, we propose a multilevel conceptual framework in Figure 1. In this framework, disconnected describes young people who do not attend school and are not employed (Levitan, 2005). Social exclusion, a “deeper” social process, refers to the economic, housing, medical, political, and spatial exclusion of selected groups (Social Exclusion Unit, 2000; Young, 2007). As shown in Figure 1, structural factors such as changes in the global economy, together with national and local educational, drug, and welfare policies shape the options for school and work available to, in this case, young men of color. The framework posits that the incarceration experience exacerbates disconnectedness among poor, young men of color, contributing to social exclusion.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework for the relationship between incarceration and social exclusion.

Specifically, the framework shows that policies that are based on broader social and economic trends influence who gets access to schooling and employment. For a variety of reasons, policing and criminal justice policies disproportionately target those who have not completed school or found work. For example, Pettit and Western (2004) found that Black male high school dropouts had a 59% chance of being incarcerated, compared to an 18% chance for those who completed high school. Incarceration risk varies by race, as well. White high school dropouts had only an 11% chance of being incarcerated. Others have found that many Black young men experience the real threat of incarceration during ordinary activities such as employment, hospital visits, and while hanging out (Goffman, 2009). Additionally, the postincarceration experience and reentry policies further block access to work or education, lead to subsequent criminal justice involvement, and ultimately contribute to an even more profound exclusion from mainstream adult society.

New York City provides an interesting “lab” for studying this relationship between incarceration and social exclusion in the target population. Many residents of this urban center are racial and ethnic minorities, who often reside in segregated, underserved neighborhoods (e.g., neighborhoods that lack the economic, educational, and health care opportunities available in better-off areas). To some extent, these neighborhoods are cut off from the rest of the city and country. Residents who return to these neighborhoods from New York City jails find the same lack of resources and opportunity that contributed to their incarceration (Clear, 2007). Researchers can apply the findings from this study to other urban areas in the United States and elsewhere by examining location-specific policies and trends that mediate the relationship between incarceration and social exclusion.

Disconnectedness and Social Exclusion

Several researchers have defined disconnection as a lack of participation in key social activities, most often education and employment (Besharov, 1999; MacDonald & Marsh, 2001). Disconnected youth are at higher risk of drug abuse, crime, teen pregnancy, and other adverse outcomes (Besharov, 1999; MacDonald & Marsh, 2001; Resnick et al., 1997).

The report “Out of School, Out of Work … Out of Luck? showed that in 2000 about one half of New York City youth age 16 to 24 (51.3%) were in school; one fourth (27.4%) were working, but not in school; 5.3% were seeking work and not in school; and 16.2% (about 170,000 young people) were “disconnected youth” not seeking work or attending school (Levitan, 2005). Older youth, Blacks, and Latinos were more likely to be disconnected.

As noted above, social exclusion is a broader process referring to economic, political, and spatial exclusion, in addition to being disconnected from educational opportunity, medical services, housing, and security (Social Exclusion Unit, 2000; Young, 2007). In this article, we argue that socially constructed and politically determined structures and policies exclude selected people, in particular young men of color in the United States. One consequence of this exclusion is that these young men miss the benefits of citizenship such as voting or political participation, further depriving them of opportunities to improve their circumstances (Young, 2007). Social exclusion can thus be viewed as a more fundamental cause (Link & Phelan, 1995) of the social problems of incarcerated youth, rather than the behavioral patterns that are often the focus of social and health researchers, for example, criminal activity or drug use (Daniels, Crum, Ramaswamy, & Freudenberg, 2011). Our goal in the next section of the article is to illustrate how disconnection increases risk for incarceration, by examining the intersection of economic trends, gender, race, and specific educational, drug, and welfare policies.

Structural Factors: Changes in the Economy and Opportunity for Men of Color

Levitan (2007) provided evidence that in recent years the employment prospects for young men of color have decreased steadily in New York City. Although unemployment rates decreased overall between 2001 and 2008, young people (Black and Latino men in particular) have actually seen fewer employment opportunities in recent years. In the current postrecession period, conditions have only worsened. Only one in four young Black men is employed, and the unemployment rate among 16- to 24-year-old Black men is 2.5 times as high as the New York City average (Holder, 2010). Sadly, the stagnant employment rates among teens do not reflect and are not caused by increased enrollment in schools (Levitan, 2007).

Rather, changes in those industries with high concentrations of Black male employees may explain the community’s higher rates of unemployment (Levitan, 2007). For example, Black males in the United States are overwhelmingly employed in the public sector (19% in 2000), as well as in four other private sector industries (construction, transportation, trade, service) that employ almost 60% of all Black men. Between 2000 and 2003, these five sectors lost more than 100,000 jobs in New York, a 50% decline in the number of available jobs. The current economic crisis has resulted in even more jobs lost.

Similar trends contribute to gender disparities in employment, although these trends are more specific to local economic forces, such as a decrease in jobs in manufacturing, transportation, and public utilities—labor markets that have sustained the male labor force in preceding decades (Levitan, 2005). Levitan (2007) reported that compared with women, men often work in industries that are more affected by trends in the business cycle. The Out of School, Out of Work … Out of Luck? report showed that two thirds of 16- to 24-year-old disconnected males had not worked in the prior year in the formal economy, and one half had not worked in the past 5 years (Levitan, 2005). Although New York males have had lower rates of labor market participation compared with their national counterparts, females in New York have been doing much better over the years, almost meeting national rates.

These employment trends undermine the commitment to work that defined the careers of prior generations of men of color—a dynamic exacerbated by a lack of social capital for navigating new labor markets (Anderson, 2000; Bourgois, 1995). In an ethnographic study of drug-selling markets in Harlem, Bourgois (1995) showed that first-wave Puerto Rican immigrants found ample low-waged semiskilled work opportunities in factories in New York in the 1950s. Those jobs were replaced with low-wage jobs in white collar markets, such as mailroom clerks, inventory jobs, and porters. Bourgois showed that young men of Puerto Rican descent often lacked the social capital to navigate these markets, even in low-wage positions when jobs were available. Some didn’t have driver’s licenses, whereas others lacked basic education and training and were generally unable to navigate the bureaucracies of these low-wage white collar positions. Moreover, Bourgois claimed that the low wages and lack of respect young Puerto Rican men experienced in these workplaces often made jobs in the illicit economy seem preferable. But these jobs in the illegal economy put people at risk for incarceration.

Similarly, Anderson (2000) investigated the loss of manufacturing jobs in Philadelphia that precipitated the movement of working-class Black families out of their old neighborhoods in search of new opportunities. As a result, old urban Black neighborhoods were left without jobs and community institutions like churches and youth organizations, rendering the neighborhoods susceptible to a restructuring of housing developments in the face of outmigration patterns and urbanization policies. Eventually, new “codes” of the street—often associated with violence—emerged due to the loss of community infrastructure.

This increasing breakdown of community structures like school and work led some urban young men of color to turn to gangs and peers for protection, support, and income, limiting their prosocial involvement. In a study of New York City gangs in the 1990s, Brotherton and Barrios (2004) attributed increased gang involvement to, among other factors, the decrease in employment opportunity for Latino immigrants, low school funding and overall achievement, and the massive buildup of incarceration. Furthermore, jails often serve as prime recruiting venues for youth gangs, and high rates of incarceration thus facilitate their expansion. Vigil (2002) demonstrated that immigrants, mostly Mexican youth, in Los Angeles often found the necessary social controls and solidarity in gangs, which served as an antidote to the multiple marginalities they faced in their new communities. However, by joining gangs, young men may become further excluded from their own communities and mainstream society and be at higher risk for police targeting or serving jail time because of gang-related illegal activities.

Gender

These trends in employment and education also affect opportunities differentially according to gender. As service and other low-wage job sectors have expanded, young women’s employment prospects have improved somewhat, although young women age 16 to 24 in New York City still have lower rates of labor force participation than young men. They also have higher rates of school enrollment, improving later job prospects (Levitan, 2005).

For young men, fulfilling traditional masculine roles may contribute to differential work and school opportunities. As employment opportunities modestly expand for women and contract for men some men may revert to more patriarchal forms of masculinity to maintain a sense of self-worth. Such masculinity is characterized by more traditional (patriarchal) gender roles, less willingness to assume parental roles, and a greater propensity toward violence within intimate relationships (Barker, 2005).

Researchers theorize that there are different paths to masculinity, and that social and economic conditions can push young men of color down one path or the other (Anderson, 2000; Whitehead, 1992). Whitehead (1992), for example, wrote about two particular paths—one of respectability, characterized by males who were strong economic providers, married, homeowners, and had an education; and one based on reputation, where males gained power through sexual prowess, toughness, defiance, and fathering many children. As is the case with employment opportunities, home ownership, and education levels, the path that is considered most respectable may be filled with obstacles, whereas the path associated with reputation may appear more accessible (Wilson, 1996).

Reputation-based masculinity becomes functional in other settings, such as in jail, with the drug trade, or on the streets (Payne, 2006). It can also be associated with gaining respect in a community, as Hill Collins (2004) and Bourgois (1995) argued, pointing out that young men of color are actively seeking the respect they are unable to get in other settings. This search for respect translates to a search for economic and social opportunities within the confined structures of their daily lives—including limited opportunity that can drive men to illegal work in the drug trade, street vending, or under-the-table labor in the “gray” economy. Notably, these paths significantly increase the risk for incarceration, thus exacerbating disconnection.

Race

Levitan (2005) also reported differences in school and work engagement by race/ethnicity—the majority of “disconnected youth” in the study are Black and Latino. Black youth make up the largest portion of those left out of the labor market, whereas Latino youth have the lowest school enrollment rate. Overall, Black and Latino young men in New York City are twice as likely to be disconnected as Whites (16.6% for Black vs. 16% for Latinos and 7.6 % for Whites). Hill Collins (2004) argued that racial/ethnic minorities face a closing door of opportunity when it comes to employment opportunities, education, equitable housing, and neighborhood integration. For example, within the Black community, she tied this disenfranchisement to a history of slavery, segregation, and urban dislocation. For Latinos, opportunity may be related to immigration status but also to marginalization from mainstream institutions, such as schools (Bourgois, 1995).

In its consequences, high rates of disconnection put young Blacks and Latinos at multiple jeopardy for arrest and incarceration. First, access to gainful employment provides income, which may reduce the need to engage in illegal activity (Sullivan, 1989). More specifically, labor force participation reduces the pressure to participate in the informal or illegal economy, further reducing the risk of arrest. Second, when it comes to education, schools—compared to communities—have the potential to provide safe environments for young people, although low-income, urban youth do report experiencing violence and lack of safety in schools (Fine et al., 2003). Finally, police are much more likely to stop and frisk Black and Latino youth than their White peers, specifically in New York City communities (Spitzer, 1999). By sheer probability, being out of school and work puts these young men at higher risk for police encounters.

Public Policies Leave Young Men of Color Vulnerable for Incarceration

In the past three decades, numerous public policies around education, drugs, and welfare have contributed to the disconnection of young men of color, whether intended. These policies, which have been implemented at the city level in New York as well as nationally, result in leaving young men vulnerable to targeting by the criminal justice system.

In New York City, Treschan and Molnar (2008) estimated that publicly funded education and vocational programs serve only 18% of the disconnected youth in need. Additionally, of the young people who are served by these programs, the majority are placed in programs planned by and for older adults, reducing their effectiveness and reach with young people. Even students who do attend school can be deterred from completion by educational policies such as high stakes testing or zero-tolerance disciplinary procedures. New York City also does not allow young people older than age 21 to earn a high school diploma, even though two thirds of disconnected youth are between age 20 and 24 (Treschan & Molnar, 2008). Instead, older youth are encouraged to earn General Equivalency Diplomas (GEDs), a credential whose value for higher education and employment is frequently questioned (Tyler, 1998).

Unfortunately, older youth are also generally unwilling to return to high schools where they have previously failed. Treschan and Molnar (2008) found that these youth would rather attend smaller community-based programming to receive high school equivalency, but only one such program exists specifically for disconnected youth in New York City. Furthermore, this program has only 5,500 slots for the 85,000 disconnected youth without a high school diploma or GED. For the most part, New York City Department of Education policies and funding target those youth already in high school, but at risk for dropping out—not those who are altogether disconnected (Treschan & Molnar, 2008).

Nationally, high school graduation enrollment rates for Blacks and Latinos are disproportionately low. In a national study of high school graduation rates by racial/ethnic groups and gender, whereas 70.8% of White males graduated, only 42.8% of Black males and 48% of Latino males finished on time (Swanson, 2004). In addition, Barker (2005) argued that poor minorities in urban areas may be under pressure to support their families financially, and there are more rewards for quick financial gains (often in the illegal economy) compared to staying in school. He also cited teacher stereotypes regarding low-income boys, as tough, unruly, and unteachable—characteristics that teachers have trouble addressing. Barker also notes that the nature of these male peer groups might make dropping out an acceptable option.

Finally, the federal No Child Left Behind legislation in the United States created new incentives for schools to push out or exclude students with educational and social problems. These young people lower average scores on national tests, thereby reducing a school’s overall ranking and ability to receive funding (Darling-Hammond, 2007). In New York City, young people leaving jail are often discouraged from reenrolling in school, putting them at risk of disconnection and reincarceration (Rimer, 2004).

Together these educational policies have created what some have called the school-to-jail pipeline, a pathway sanctioned by policy that pushes low-income young people of color from the school system into the correctional system. One indicator of this alarming trend is that many states now spend more on corrections than public higher education and admit more young men of color to their jails and prisons than their universities (Brotherton & Barrios, 2004; Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006; Dellums Commission, 2006).

Drug policies also increase the risk for incarceration and disconnection from school or work. Between 1996 and 2007, New York City police made 353,000 arrests for marijuana, compared to 30,000 in the previous decade. Most of those arrested spent at least one night in jail, though many with prior arrests spent more time. Most were young adults—52% were Black, and 31% were Latino—although Blacks and Latinos make up only 53% of the city’s total population (Levine & Small, 2008). Failure to make drug treatment accessible, especially for young people, also contributes to disconnection. Research shows that disconnected youth have higher rates of drug and alcohol use than their peers (Townsend, Flisher, & King, 2007). Drug use ultimately interferes with school completion and employment (MacDonald & Marsh, 2001). However, New York City, like other jurisdictions, faces an overall shortage of drug treatment slots and an acute deficit of treatment programs for young drug users, a group that does poorly in adult-oriented treatment programs (Bolas, 2005).

In a New York City jail, one study found that adult males with drug problems were 4 times more likely to get drug treatment in jail than adolescent young men with drug problems (Freudenberg, Moseley, Labriola, Daniels, & Murrill, 2007). Drug problems and lack of drug treatment consistently predict further criminal justice involvement (Broome, Knight, Hiller, & Simpson, 1996; Freudenberg, Daniels, Crum, Perkins, & Richie, 2005). These factors ultimately contribute to housing instability, because New York City public housing policies require those charged with drug crimes to be evicted (Boire, 2007). Such policies leave young drug users vulnerable to reincarceration, exacerbating their disconnection from school and work.

On a national level, other drug policies include the replacement of drug treatment and rehabilitation programs with criminal prosecution and incarceration. This shift occurred in the 1980s, and the 1990s saw the movement of young offenders into the adult correctional system, and zero-tolerance and mandatory sentencing policies that pushed youth out of public schools (Dellums Commission, 2006). These policies have resulted in increasing dropout rates and skyrocketing incarceration rates for young men of color. More recently, disinvestments in corrections due to tight state budgets and overturning of some of these drug policies have created a new policy environment. However, continuing cuts in safety net programs may be weakening supports for reentry just as more people are leaving incarceration to return to poor communities (Gar, 2011).

Other provisions of the “war on drugs” have also unfairly targeted racial minorities. For example, the stiffer penalties for crack sellers, 80% of whom are Black, than for powdered cocaine sellers, exacerbate racial disparities (Mauer, 2006). In New York, Rockefeller-era drug laws have imposed unfair mandatory minimum sentences on young, often first-time, offenders for possession of certain drugs (Chan, 2008). The majority of people targeted under these laws from the mid-1970s until 2005 were Black and Latino, despite the fact that Blacks report less drug use than Whites (Moore & Elkavich, 2008).

Welfare policies are another factor working against disconnected youths. In New York City, young people leaving the child welfare system have disproportionately high rates of homelessness. In one study, 29% of people who had been in homeless shelters had a child welfare history, and the group with the biggest burden consisted of those who had aged out of the system (Culhane & Park, 2007). Also in New York City, youth typically age out of the child welfare system at age 18, unless they are involved in approved programming, in which case they can stay in the system until age 21. Thus, the system established to protect vulnerable children discharges many of its clients without high school diplomas, employment skills, or for some, even safe shelter. Not surprisingly, youth involved in the child welfare system are thus at risk for involvement in the criminal justice system (Jonson-Reid & Barth, 2000).

After the 1996 welfare reform laws were enacted, 500,000 New Yorkers lost cash assistance and food stamps by 2000 (Bloomberg, 2003). To cut costs and dependency on welfare benefits, New York City changed eligibility standards and created barriers to enrollment (Chernick & Reimers, 2001). A judge later found that the City violated federal laws by creating some of these barriers (Houppert, 1999). Last, studies demonstrate that women are much more likely to receive public benefits than men, especially adolescent men. For example, despite the fact that almost all participants in one jail-based study met eligibility criteria for public benefits, 51% of women but less than 1% of adolescent men actually reported receipt of public benefits (Freudenberg et al., 2005).

Nationally, welfare policy has always been designed primarily to serve single mothers and their children, often excluding targeted benefits for young men. Although welfare policy is supposed to encourage people to work, the policies do not address the persistence of disconnection and stigma associated with incarceration histories and the problems they pose for Black or Latino youths looking for work (Pager, 2003). As a result, young men of color—a sector of the population with some of the highest rates of unemployment and poverty—are left without even the inadequate safety net programs that could mitigate their difficult circumstances. This lack of support provides further incentives for participation in the illegal economy and subsequent risk for incarceration (Freudenberg et al., 2005).

In sum, a cascade of policies in multiple sectors function to separate young people of color from school, employment, housing, and public benefits—the very support systems that could serve as an antidote to disconnection. As a result, these young people become targets for another set of policies—in policing, public safety, criminal justice, and drugs—that put them at risk of incarceration. In the next section, we conduct an empirical analysis to explore how incarceration can push disconnected youth further into social exclusion.

THIS STUDY

To examine the dynamics of disconnectedness for young men in urban areas and to illustrate the pathways between disconnectedness, incarceration, and social exclusion, we present data on school and work participation, recidivism, housing stability, and health care coverage for a group of 16- to 18-year-olds recruited and interviewed in a New York City jail, and then interviewed again one year after they were released. Thus, we follow a cohort of young people from the time they were incarcerated (Time 1, intake interview) to one year after they were released from jail (Time 2, follow-up interview). This provides an opportunity to examine the rates and correlates of disconnection and social exclusion over time for a sample of incarcerated young men. Our primary dependent variables were indicators of social exclusion—school and employment characteristics after release from jail, recidivism, stable housing, and health care coverage. These variables were selected based on the literature on social exclusion, and the data that were available to us given our sample population. Our independent variables included indicators of disconnection from school and work, as well as background characteristics that may be related to social exclusion. We hypothesized that our sample of urban, young Black and Latino men are already disconnected from school and work prior to their incarceration. Criminal justice policies, and the incarceration experience in particular, exacerbate disconnection and contribute to the young men’s social exclusion into early adulthood.

METHOD

Data and Sample

The young men described in this article were participants of the REAL MEN study (an acronym for Returning Educated African-American and Latino Men to Enriched Neighborhoods) (Daniels et al., 2011, Freudenberg et al., 2010). Participants were recruited from two facilities at the New York City Department of Correction, Rikers Island Detention Center. The study was part of an intervention designed to reduce HIV risk, substance use, and recidivism for incarcerated young men in New York City. Study protocols were approved by the Hunter College Institutional Review Board. All interviews were conducted from 2002 to 2007. Eligible males age 16 to 18 years were recruited in the study. The sample resembled the adolescent population leaving New York City jails on demographic and criminal justice characteristics. At intake, 552 young men consented to complete an interview, and all responses from this interview refer to their situation immediately preceding arrest/incarceration. One year after release from jail, 397 of the men (72%) completed the follow-up interview. Because we compare data from Time 1 and Time 2, we present data on the 397 participants who completed both interviews.

First, to provide background on demographic and criminal justice characteristics before incarceration and after release from jail, we present data on age, race, living situation and housing instability, health care coverage, education, and involvement with the criminal justice system. Second, variables selected for the analysis in this article are based in part on those presented in the study on “disconnected youth” in New York City (Levitan, 2005). Therefore we analyze the following data: school participation and labor participation before incarceration and one year after release from jail. Finally, to examine indicators of social exclusion that we could measure with the REAL MEN study data, we analyze lack of school attendance, unemployment, housing instability, recidivism, and lack of health care coverage at Time 2. We selected these five outcomes based on definitions of social exclusion in the literature, that is, exclusion from educational opportunity, employment, housing, and health care, and because we are studying a sample of recently released inmates, we also included recidivism; relevant changes in Time 1 and Time 2 data shown in bivariate analyses; and last, our own research about the relationship between health care coverage and disadvantage (Freudenberg et al., 2005; Social Exclusion Unit, 2000; Young, 2007).

To meet the standard definition of disconnectedness in this study, our in school measure includes those who reported being enrolled in school and attending most of the time. Respondents who said they did not attend school most of the time were considered “out of school” because our experience suggests that youth delay officially dropping out until long after they stop attending. The variable in labor force includes all youth, not just those out of school (unless otherwise specified in Table 1), and those who are unemployed but looking for work. We define disconnected as anyone not enrolled in school and not in the labor force. For employment we include anyone who reported full-time, part-time, or off-and-on work.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Young Men Prior to Incarceration and One Year After Release From Jail, N = 397

| Time 1 (%) | Time 2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 17.99 (SD = 0.71)* | 19.60 (SD = 0.93) |

| Race/Ethnicitya | ||

| Black, non-Latino | 55.8 | —— |

| Latino | 38.1 | —— |

| Housing | ||

| Live with parents, legal guardian or other family | 89.9** | 62.1 |

| Live alone, with friends, or other partner | 7.6 | 13.0 |

| Unstable or institutional housing | 2.5** | 24.8 |

| Homeless in past year | 5.5** | 9.3 |

| Ever been in child welfare system | 27.0 | —— |

| Health care coverage in past year | ||

| Paid for medical care with Medicaid or other health insurance | 93.2* | 75.7 |

| Education prior to arrest (since release at T2) | ||

| Had not completed tenth grade | 35.8** | 15.3 |

| Completed high school or General Equivalency Diploma | 6.8** | 26.8 |

| Ever held back a grade in school | 48.4 | —— |

| Current school and employment characteristics | ||

| In school | 32.0 | 20.3 |

| In labor force | 66.5 | 67.3 |

| Out of school and in labor force | 43.7 | 56.5 |

| Out of school, in labor force, and employed | 21.3 | 19.1 |

| Disconnected (not in school or labor force) | 24.4 | 23.6 |

| Involvement with criminal justice system prior to arrest | ||

| 1–3 prior arrests | 40.1 | —— |

| 4–9 prior arrests | 35.0 | |

| 10 or more prior arrests | 15.4 | |

| Prior incarcerations | 66.5 | |

| Involvement with criminal justice system since release | ||

| Number of rearrests in past year | —— | 1.43 (SD = 1.58) |

| Percent reincarcerated in past year | 46.9 | |

| Average length of reincarceration (days) in past year | 84.92 (SD = 119.89) | |

Other race categories: Other (4.0%); Biracial (1.0%); White, non-Latino (1.0%).

p < 0.001,

p < 0.05.

Unstable housing is defined as any experience of living in a shelter, living from place-to-place, homeless, living on the streets, in an empty building, or in an institution. Recidivism is defined as having an incarceration in the one-year interval after release from the index incarceration. Lack of health care coverage includes those who reported not having Medicaid or some other health insurance to pay for medical care (currently at Time 1 and in the past year at Time 2). Independent variables were Time 1 age, race/ethnicity, child welfare history (involvement in Administration for Children’s Services—the New York City child welfare agency, a group home, or foster care), not living with parents or a legal guardian, having unstable housing, no health care coverage, number of previous arrests, no school attendance, and no labor market participation. Indicators of social exclusion listed above were also added as independent variables, in order to assess the relationship between these Time 2 characteristics and each dependent variable.

To compare demographic, criminal justice, and disconnectedness data we used a z-test to compare column proportions for all ordinal variables at Time 1 and Time 2 (Healey, 2004). We used logistic regression to measure the relationship between dependent and independent variables (Morgan & Teachman, 1988). Model I was run with the Time 1 independent variables. Model II added four of five indicators of social exclusion at Time 2 to be analyzed with each dependent variable. Model II therefore controls for all Time 1 background characteristics. We assessed logistic regression coefficients (B’s) and odds ratios (Exp (B)) in each model. We tested model significance with the χ2 omnibus test for model coefficients and used the Nagelkerke R2 to assess model fit. All analyses were conducted with SPSS Version 16.1.

Participants in this study were male, and most were Black (55.8%) and Latino (38.1%) (Table 1). The mean age at the time of the intake interview was 17.99 (SD = .71). One year after release from jail, the mean age of participants was 19.60 (SD = .93), suggesting that on average young men spent 7 months in jail prior to release. Participants who completed the follow-up interview one year after release from jail were more likely to live with parents or a legal guardian, less likely to have status violation charges, and more likely to be diagnosed with asthma (p < 0.05).

FINDINGS

Disconnection

A comparison of the proportions of young men who were attending school and/or work during Time 1 and 2 shows that there was little change between these periods (see Table 1). Although the proportion in school decreased by 36% and the proportion of out of school and in the labor force increased by 29%, these changes did not achieve statistical significance. At Time 1 and 2, about one fourth of the young men were disconnected, meaning they were out of school and out of work. This rate is 50% higher than the rate reported for the 20- to 24-year-olds in the report on New York City youth, a representative group of noninstitutionalized young people in New York City (Levitan, 2005).

Education

At the time of the index arrest/incarceration, more than one third (35.8%) of the young men had not completed 10th grade, and almost one half (48.4%) had been held back a grade at least once. Very few (6.8%) had completed high school or a GED program. At the 1-year follow-up interview, another 20% of the sample had finished high school or a GED program, a significant increase (p < 0.05). However, almost three fourths (73.2%) had still failed to complete high school at the average age of almost 20. Age (odds ratio [OR] = 1.37 at Time 1, OR = 1.39 at Time 2) and number of previous arrests prior to incarceration (OR = 1.42 at Time 1, OR = 1.44 at Time 2) were associated with no school attendance at Time 2 in Model I and Model II (see Table 2). None of the Time 2 indicators was associated with lack of school attendance.

TABLE 2.

School, Work, Recidivism, Housing, and Health Care for Young Men One Year After Release from Jail, N = 397

| Dependent Variables - One year after release from jail | No school attendance OR (B)

|

Unemployment OR (B)

|

Recidivism OR (B)

|

Unstable housing OR (B)

|

No health care OR (B)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II |

| Value at Time-Prior to Incarceration | ||||||||||

| Age (Mean = 17.99) | 1.37*** (0.32) | 1.39*** (0.33) | 1.02 (0.02) | 1.03 (0.03) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.90 (−0.10) | 1.24 (0.22) | 1.25 (0.22) | 1.66* (0.51) | 1.59** (0.47) |

| Black (55.8%) | 2.31 (0.84) | 2.18 (0.78) | 0.84 (−0.17) | 1.44 (0.36) | 0.74 (−0.30) | 0.93 (−0.07) | 0.52 (−0.65) | 0.42 (−0.87) | 3.04 (1.11) | 3.35 (1.21) |

| Latino (38.1%) | 1.91 (0.65) | 1.84 (0.61) | 0.89 (−0.12) | 1.35 (0.30) | 1.03 (0.03) | 1.13 (0.13) | 0.92 (−0.08) | 0.77 (−0.26) | 3.03 (1.10) | 2.91 (1.07) |

| Child welfare history (27.0%) | 0.87 (−0.14) | 0.94 (−0.06) | 2.13*** (0.76) | 1.82 (0.60) | 1.67*** (0.51) | 1.34 (0.29) | 1.94*** (0.66) | 1.48 (0.39) | 1.36 (0.31) | 1.25 (0.22) |

| Not living with parents/guardian (10.1%) | 1.00 (−0.01) | 1.07 (0.07) | 0.80 (−0.22) | 0.65 (−0.43) | 1.11 (0.10) | 0.93 (−0.08) | 1.61 (0.48) | 1.90 (0.64) | 0.76 (−0.27) | 0.69 (−0.37) |

| Unstable housing (2.5%) | 0.61 (−0.49) | 0.72 (−0.33) | 3.99E8 (19.81) | 3.07E8 (19.54) | 0.56 (−0.58) | 0.30 (−1.18) | 2.01 (0.70) | 2.35 (0.86) | 2.76 (1.02) | 2.54 (0.93) |

| No health care (6.8%) | 3.62 (1.29) | 3.23 (1.17) | 0.57 (−0.56) | 0.65 (−0.43) | 1.80 (0.59) | 2.10 (0.74) | 0.79 (−0.23) | 0.03 (−1.16) | 6.86* (1.93) | 7.15* (1.97) |

| Number of previous arrests (Mean = 5.35) | 1.42*** (0.35) | 1.44*** (0.36) | 1.18 (0.16) | 1.19 (0.17) | 1.33*** (0.29) | 1.23 (0.25) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) |

| No school attendance (68.0%) | 1.60 (0.47) | 1.62 (0.48) | 1.31 (0.27) | 1.34 (0.29) | 1.44 (0.36) | 1.53 (0.43) | 0.97 (−0.03) | 0.72 (−0.33) | 0.70 – (0.35) | 0.71 (−0.36) |

| Not in labor force (33.5%) | 0.74 (−0.31) | 0.77 (−0.26) | 1.45 (0.37) | 1.38 (0.32) | 1.19 (0.18) | 1.07 (0.07) | 1.41 (0.35) | 1.32 (0.28) | 0.99 (−0.01) | 0.90 (−0.10) |

| Omnibus test of model coefficients χ2 (p value) | 22.96 (0.011) | —— | 14.98 (0.133) | —— | 20.43 (0.025) | —— | 18.64 (0.045) | —— | 33.19 (0.000) | —— |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.107 | —— | 0.071 | —— | 0.082 | —— | 0.083 | —— | 0.147 | —— |

| Value at Time 2-One Year After Release from Jail | ||||||||||

| No school attendance (79.7%) | —— | —— | —— | 0.53 (−0.63) | —— | 1.40 (0.34) | —— | 0.61 (−0.49) | —— | 1.32 (0.28) |

| Unemployment (77.0%) | —— | 0.58 (−0.55) | —— | —— | —— | 1.52 (0.42) | —— | 13.61* (2.61) | —— | 0.79 (−0.24) |

| Recidivism (46.9%) | —— | 1.39 (0.33) | —— | 1.48 (0.39) | —— | —— | —— | 9.04* (2.21) | —— | 1.09 (0.08) |

| Unstable housing (24.8%) | —— | 0.56 (−0.59) | —— | 11.49* (2.44) | —— | 8.36* (2.12) | —— | —— | —— | 2.60** (0.96) |

| No health care (24.3%) | —— | 1.24 (0.22) | —— | 0.76 (−0.27) | —— | 1.09 (0.08) | —— | 2.86** (1.05) | —— | —— |

| Omnibus test of model coefficients χ2 (p value) | —— | 28.60 (0.012) | —— | 44.51 (0.000) | —— | 76.03 (0.000) | —— | 103.10 (0.000) | —— | 42.47 (0.000) |

| Nagelkerke R2 | —— | 0.132 | —— | 0.201 | —— | 0.281 | —— | 0.406 | —— | 0.186 |

OR = odds ratio.

p < 0.001,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

Employment

During the intake interview, the young male participants reported that in the year prior to incarceration, 66.5% had some form of employment. A year later, the proportion working had not changed. In Model I, child welfare history at Time 1 (OR = 2.13) was associated with unemployment at Time 2. However, in Model II the effect of child welfare history decreased and became nonsignificant. Model II also showed that those participants with unstable housing (OR = 11.49) at Time 2 were more likely to be unemployed than those with stable housing.

Criminal Justice Involvement

Prior to the index arrest/incarceration, 75.1% of the interviewees had between one and nine prior arrests, 15.4% had 10 or more arrests, and 66.5% of the sample had experienced at least one prior incarceration. One year after release from jail, participants had an average of 1.43 (SD = 1.58) new arrests. Almost 47% had been reincarcerated in the past year, and those reincarcerated said they spent an average of 84.92 (SD = 119.89) days in jail in the one year after release. Model I showed that child welfare history (OR = 1.67) and previous number of arrests prior to incarceration (OR = 1.33) were associated with recidivism. In Model II, the effects of both of these factors decreased and became nonsignificant. Furthermore, unstable housing at Time 2 (OR = 8.36) became a correlate of recidivism. In a separate analysis (not shown in Table 2) to assess the contribution of length of incarceration between Time 1 and Time 2 to indicators of social exclusion, we found that young men with more than 10 days of incarceration between interviews (the median length of incarceration for the sample) were 27 times as likely to be unstably housed at Time 2 compared to those men with 10 days or fewer of incarceration (OR = 27.50, p < 0.000).

Housing

At Time 1, the majority of participants (89.9%) reported living with parents, a legal guardian or other family. One year after release from jail, as expected for older adolescents, the proportion of young men living alone, with friends or with partners was about the same (7.6% at Time 1 vs. 13.0% at Time 2), although the proportion of people living with parents or family declined significantly (89.9% at Time 1 vs. 62.1% at Time 2) (p < 0.05). Not surprisingly, the proportion living in either unstable living situations or institutional housing increased significantly (2.5% at Time 1 vs. 24.8% at Time 2) (p < 0.05). At Time 1, one third of all participants had been involved in the child welfare system, At Time 2, a higher rate of participants reported homelessness in the one year after release than at intake (5.5% at Time 1 vs. 9.3% at Time 2) (p < 0.05). Those with a child welfare history at Time 1 (OR = 1.94) were almost twice as likely to have unstable housing at Time 2. However, when adding Time 2 indicators in Model II, the effect of child welfare history decreased and became nonsignificant. Model II showed that unemployment (OR = 13.61), recidivism (OR = 9.04), and lacking health care coverage (OR = 2.86) at Time 2 were associated with unstable housing at Time 2.

Health Care

Regarding health care at Time 1, 93.2% of participants reported that they had Medicaid or another form of health insurance in the past year. By Time 2, this proportion decreased, with only 75.7%% reporting health care coverage (p < 0.001). Age (OR = 1.66) and not having health care coverage at Time 1 (OR = 6.86) were associated with not having health care coverage at Time 2. In Model II, age (OR = 1.59) and not having health care at Time 1 (OR = 7.15) were still significant correlates of health care coverage at Time 2, but in the second model those who had unstable housing (OR = 2.60) were more likely to not have health care coverage at Time 2.

DISCUSSION

These data demonstrate that at the individual level, urban, young men of color involved in the criminal justice system in the United States are already facing greater disconnection compared to the general population of their peers before they are ever incarcerated. Additionally, incarceration further worsens their ability to meet important educational and employment standards after they are released from jail. Thus, incarceration is a cause and a consequence of disconnection. As illustrated in the conceptual model (Figure 1), after release, many young men experience school dropout, unemployment, and multiple incarcerations. Contrary to our hypothesis, the incarceration experience does not appear to exacerbate disconnectedness directly, perhaps because these young people have already achieved high levels of disconnection prior to being jailed. Incarceration is, however, associated with unstable housing, which in turn may contribute to several negative outcomes related to social exclusion: unemployment, recidivism, and lack of health care coverage. Thus, unstable housing is one of the most important correlates of social exclusion for this sample and may be just as important as the incarceration experience in its association with social exclusion for a group of disconnected young men in New York City. Future studies comparing unstably housed but never incarcerated young men with those who have experienced incarceration may clarify the role of these two risk factors for disconnection. Here we review the education, employment, criminal justice, housing, and health care outcomes of the young men in this study. We also identify postincarceration policies and trends that disconnect young men and thereby contribute to social exclusion into adulthood.

After incarceration, one half of the young men who had not completed the 10th grade prior to the index arrest/incarceration went back to school and finished the 10th grade after being released from jail. By Time 2, almost 4 times as many young men had completed high school or its equivalent as at Time 1 (26.8% vs. 6.8%). This shows that finishing school after an incarceration is certainly possible.

However, only about one fourth of the young men in this study had completed high school or the GED at Time 2. According to New York City school data about 35% of Black and Latino young men entering high school in 2002 had graduated by 2006 (New York City Department of Education, 2008). In other words, the men in this sample—all of whom served jail time—had a school completion rate that was only 76% of the already dismal completion rate for the general population of young men of color. In assessing the relationship between disconnection, incarceration, and social exclusion, we found a relationship between lack of school attendance (including aging out of school) and criminal justice involvement. This was only worsened by the previously described barriers to education, such as lack of community and government investment in high school education, and minimal services to help people older than age 18 to complete school (Treschan & Molnar, 2008). Given that 60% of people in American jails lack a high school diploma—and that it is extremely difficult to reconnect with the educational system upon leaving jail—the pathways for finding postincarceration education are narrow at best (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2003; Rimer, 2004).

Employment rates for young men leaving jail are also discouraging. Although more of the interviewees participated in the labor force at Time 2 (perhaps because of older age and lower school enrollment), the proportion that were out of school, in the labor force, and actually employed didn’t change significantly during this interval. Among all New York City youths, 4 times the proportion of 20- to 24-year-old males were in the labor force as were 16- to 19-year-old males (Levitan, 2005), suggesting that young men with incarceration experience are less successful in transitioning into the formal labor force than their peers in the general population.

The rate of disconnectedness did not vary between interviews. We expect that at the index incarceration participants were still young enough to go back to school. But because some spent more than 6 months in jail during the index incarceration, and almost one half were reincarcerated the year after release from jail, it is likely to become increasingly difficult for them to reengage with school and work. Many of the young men have a history of multiple incarcerations, which often leads to employer discrimination and in turn, a high risk that these young men could return to jail for a minor infraction (Gonnerman, 2004; Pager, 2003). Thus, multiple incarcerations in the teen years appear to deter school completion, putting young men at risk of continuing employment difficulties.

Anyone with criminal justice involvement faces extraordinary barriers to employment, including discrimination and prohibition from certain government jobs and positions requiring special licenses (Holzer, Raphael, & Stoll, 2003). Disconnected men of color face the triple burden of racism, incarceration records, and fewer educational opportunities (Pager, 2003). Higher rates of substance abuse and mental health problems among unemployed youth create further barriers to finding and keeping a job (Cotton-Oldenburg, 1999; Lundgren, Amodeo, & Chassler, 2005. Thus, institutional obstacles to employment and education, discrimination based on race and a criminal justice record, and the negative health consequences of unemployment push the young men we studied down the path of disconnectedness into the deeper waters of social exclusion.

Almost one half of the men in this study were reincarcerated between the Time 1 and Time 2 interviews; those reincarcerated were 9 times more likely to have unstable housing situations than their unincarcerated peers. Those incarcerated for more than 10 days between interviews were 27 times as likely to be unstably housed, a finding that actually quantifies the short length of incarceration harmful to young men. Other studies have shown that recidivism predicts poor educational and employment outcomes, family and housing instability, and a lack of community and social cohesion (Black & Cho, 2004; Freudenberg et al., 2005; Holzer et al., 2003; Taxman, Byrne, & Pattavina, 2005). In the current analysis, however, housing instability was by far the strongest correlate of social exclusion.

Many more people reported unstable housing conditions or institutional housing at Time 2 (24.8% compared to 2.5% at Time 1), which suggests that finding housing is a significant burden for young men leaving jail, most likely because many leave their parents or guardians after they turn age 18 and move to a more unstable living situation. It is also worth noting that prior to the index arrest/incarceration, a significant proportion of young people (27.0%) were involved in the child welfare system. Young men who spent any amount of time in the child welfare system were significantly more likely to face unemployment, recidivism, and unstable housing postrelease. Those participants with unstable housing postincarceration (one fourth of this sample) were 11 times as likely to be unemployed, 8 times as likely to be reincarcerated, and almost 3 times as likely to not have health care. Nationally, people leaving prison also find it difficult to secure housing upon reentry into their communities which illustrates why a majority of the homeless population has a criminal justice history (Re-Entry Policy Council, 2005).

Depending on the nature of the criminal record, some state laws restrict or ban a former inmate’s public housing eligibility altogether (Roman & Travis, 2004). Local public housing authorities also have broad discretion when it comes to denying housing eligibility based on perception of risk (Human Rights Watch, 2004). New York City Housing Authority, in particular, has the right to ban individuals and their families for differing lengths of time for anyone age 16 years or older for a range of problems, from sex offenses to drug use history, including marijuana use (Legal Action Center, 2006). Researchers have also demonstrated how vulnerable homeless populations are to high-risk sexual behavior, drug abuse, and infectious diseases such as HIV (Cotton-Oldenburg, 1999). In sum, housing instability after reentry from incarceration puts young people at continuing risk of criminal justice involvement and adult homelessness, an extralegal postrelease extension of sanctions. Finally, the proportion of young men with health insurance coverage decreased from Time 1 to Time 2 (93.2% vs. 75.7%). As young men turn age 18 or move out of their family household, they may lose health insurance coverage. Given that so few are finding employment and that low-wage employers seldom provide health insurance, it is unlikely that they receive health care coverage from employers. Prior studies show that having health care coverage or continuity of health care postincarceration is inversely related to rearrest, reincarceration, drug use, and drug sales (Lee, Vlahov, & Freudenberg, 2006; Sheu et al., 2002).

Although this study did not directly measure political participation, spatial exclusion, or the subjective experience of marginalization, further research can more fully explore how these factors are related to disconnection, especially given ample evidence of voter discrimination and spatial segregation. For example, in 32 states felons cannot vote while on parole, a policy that excluded 13% of Black men from voting in the United States in 1998 (Iguchi et al., 2002). In New York City, one half of all former inmates leaving jails return to just seven of the poorest of New York City 59 neighborhoods (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2002). This marginalization is reflected in young minorities’ perceptions of police and the criminal justice system. Although researchers have demonstrated that the criminal justice system targets Black and Latino people more frequently than their White counterparts, research has also shown that Black and Latino youth actively perceive such injustice and betrayal by adult authority figures not only in the criminal justice system, but in schools (Fine et al., 2003; Hagan, Shedd, & Payne, 2005). This makes it difficult for them to trust the very program—the educational system—that could keep them out of jail.

The evidence presented above illustrates how the postincarceration experience and reentry policies affect the educational and employment prospects of the young adults described in this study. Criminal justice involvement strips the benefits of citizenship and inclusion of young men of color in the United States, limiting educational and employment opportunity, and political participation. This study also suggests that as these young men age, the patterns of disconnection and exclusion described here may influence longer term and increasingly negative criminal justice, social, and health outcomes. Thus, incarceration, unstable living circumstances, and public policies may serve to exclude low-income, young, Black and Latino men in the United States from the benefits of social inclusion. As a result, we encourage policy makers and researchers to propose solutions that can reduce potential disconnection from school and work, criminal justice involvement, and social exclusion, by reengaging disadvantaged young people.

Toward Policies of Inclusion

In recent years, youth advocates, policy analysts, and researchers have observed the myriad ways that stigma and disadvantage intersect to socially exclude vulnerable youth and proposed solutions to better include especially young men of color with criminal justice histories (Taifa & Beane, 2009). We summarize some of those policy recommendations here:

Improve high school completion rates by promoting alternative high schools and easy transfer to these schools, improved special education programs, learn-to-work programs, alternative diploma/GED programs, and the tracking and modeling of successful programs to bridge the gap between high school and college for low-income underprepared students (Brown & Donnor, 2011; Canada & Parsons, 2006).

Provide career support for at-risk young adults, including those that create career pathways by offering literacy and vocational programs within correctional facilities, transitional jobs for ex-offenders, and expanded “second-chance” programs for at-risk youth (Canada & Parsons, 2006; Levitan, 2007).

Expand alternatives-to-incarceration programs that include drug treatment, community service, and ongoing educational and vocational programming in lieu of a jail sentence (New York State Division of Probation and Correctional Alternatives, 2008). Although these programs have been shown to displace jail time for misdemeanor and felony defendants and cost a fraction of the amount for jail time, to date these programs have reached only a small fraction of those who could benefit (Phillips, 2002).

Address transitional housing as an important part of the reentry process for men in late adolescence. Because they stand at a precarious point between adolescence and adulthood, young men need more flexible and age-appropriate policies and programs that help them to negotiate the transition to independent living. Policies that fail to provide ongoing housing support for young people leaving foster care or those that continue to exclude young men with drug charges from living in public housing with family members serve as major obstacles in the path to achieving housing stability (Boire, 2007).

Ensure continuity of health care coverage. Short-term health care coverage for those leaving jail or prison could provide a safety net against the health problems that can derail successful reentry and prevent recidivism (Lee et al., 2006; Sheu et al., 2002). Current public insurance programs often provide limited coverage for young women with children, but not for young men (Canada & Parsons, 2006). By making government-funded health care coverage more gender equitable, policy makers could help young men play a role in their family’s health and obtain the health care that contributes to success in school or at work. If implemented as approved by Congress, the Medicaid Expansion component of the 2010 Affordable Care Act could help to mitigate this problem (McDonnell et al., 2011).

Reduce racism and stigma in educational, workforce, and criminal justice policies to address political, spatial exclusion, and the experience of discrimination. Examples include having specific justifications for why criminal justice history questions should be included on job applications or result in trade license restrictions, such as for working as a barber. In some instances, such measures are unnecessary and add to the stigmas that prevent former inmates from reentering the workforce. In addition, policy makers should assess criminal justice and drug policies, to ensure they do not disproportionately burden racial minorities and poor neighborhoods, in part as a way to reduce actual segregation, spatial exclusion, and the subjective experience of discrimination (Chan, 2008; Fine et al., 2003; Hagan et al., 2005; Mauer, 2006). Finally, a consequence of the effect of criminal justice history on voting rights combined with the disproportionate incarceration of men of color, large segments of the Black male population are excluded from political participation (Iguchi et al., 2002). By eliminating these barriers to participation, more men of color can realize the benefits of full citizenship in the United States.

CONCLUSION

In the coming years, cutbacks in public services due to the economic downturn and conservative opposition to a robust role for government may encourage policy makers to reduce services for people leaving jail, contributing to additional disconnection and social exclusion. By acting to prevent such reductions, advocates, policy makers, and researchers can help our society avoid the high social, health, economic, and moral costs of further excluding poor, young urban men of color.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for the Returning Educated African-American and Latino Men to Enriched Neighborhoods (REAL MEN) project was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse R01 DA014725, Principal Investigator, Nicholas Freudenberg

Contributor Information

MEGHA RAMASWAMY, Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kansas, USA.

NICHOLAS FREUDENBERG, City University of New York, School of Public Health at Hunter College, New York, New York, USA.

References

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barker GT. Dying to be men: Youth, masculinity and social exclusion. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Besharov DJ. America’s disconnected youth: Toward a preventive strategy. Washington, DC: AEI Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Black K, Cho R. New beginnings: The need for supportive housing for previously incarcerated people. New York, NY: Common Ground Community and Corporation for Supportive Housing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomberg M. Mayor’s management report, fiscal year 2003. New York, NY: City of New York; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boire RG. Life sentences: The collateral sanctions associated with marijuana offenses. Davis, CA: Center for Cognitive Liberty and Ethics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bolas EJ. State of the city’s homeless youth report: 2005. New York, NY: New York City Association of Homeless and Street-Involved Youth Organizations; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. In search of respect: Selling crack in el barrio. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Broome KM, Knight K, Hiller ML, Simpson DD. Drug treatment process indicators for probationers and prediction of recidivism. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;13(6):487–491. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton DC, Barrios L. The almighty Latin king and queen nation: Street politics and the transformation of a New York City gang. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL, Donnor JK. Toward a new narrative on Black males, education, and public policy. Race, Ethnicity & Education. 2011;14(1):17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Sourcebook of criminal justice statistics, 2003. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Criminal offender statistics. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Canada G, Parsons RD. Increasing opportunity and reducing poverty in New York City. New York, NY: New York City Commission for Economic Opportunity; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. Rockefeller-era drug laws, 35 years later. New York Times. 2008 May 9; Available at http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/05/09/rockefeller-era-drug-laws-35-years-later.

- Chernick H, Reimers C. Welfare reform and New York City’s low-income population. Economic Policy Review. 2001;7:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Clear T. Imprisoning communities: How mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton-Oldenburg N. Women inmates’ risky sex and drug behaviors: Are they related? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(1):129–149. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane DP, Park JM. Homelessness and child welfare services in New York City: Exploring trends and opportunities for improving outcomes for children and youth. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels J, Crum M, Ramaswamy M, Freudenberg N. Creating REAL MEN: Description of an intervention to reduce drug use, HIV risk and rearrest among young men returning to urban communities from jail. Health Promotion and Practice. 2011;12(1):44–55. doi: 10.1177/1524839909331910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond L. Evaluating ‘No Child Left Behind.’. The Nation. 2007 May 21; Available at http;//www.thenation.com/article/evaluating-no-child-left-behind.

- Dellums Commission. A way out: Creating partners for our nation’s prosperity by expanding life paths of young men of color. Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fine M, Freudenberg N, Payne Y, Perkins T, Smith K, Wanzer K. “Anything can happen with police around”: Urban youth evaluate strategies of surveillance in public places. Journal of Social Issues. 2003;59(1):141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie BE. Coming home from jail: The social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(10):1725–1736. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Moseley J, Labriola M, Daniels J, Murrill C. Comparison of health and social characteristics of people leaving New York City jails by age, gender, and race/ethnicity: Implications for public health interventions. Public Health Reports. 2007;122:733–743. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Ramaswamy M, Daniels J, Crum M, Ompad DC, Vlahov D. Reducing drug use, human immunodeficiency virus risk, and recidivism among young men leaving jail: evaluation of the REAL MEN re-entry program. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(5):448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gar E. The landscape of recession: Unemployment and safety net services across urban and suburban America. Washington, DC: Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman A. On the run: Wanted men in a Philadelphia ghetto. American Sociological Review. 2009;74:339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Gonnerman J. Life on the outside: The prison odyssey of Elaine Bartlett. New York, NY: Picador; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Shedd C, Payne MR. Race, ethnicity, and youth perceptions of criminal injustice. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:381–407. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PM, Beck AJ. Prison and jail inmates at mid- year 2005. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hartney C, Vuong L. Created equal: Racial and ethnic disparities in the US criminal justice system. Oakland, CA: National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Healey JF. Statistics: A tool for social research. Florence, KY: Wadsworth Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Collins P. Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York, NY: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Holder M. Unemployment in New York City during the recession and early recovery: Young black men hit the hardest. New York, NY: Community Service Society of New York; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer HJ, Raphael S, Stoll MA. Employment barriers facing ex-offenders. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Houppert K. You’re not entitled: welfare “reform” is leading to government lawlessness. The Nation. 1999 Oct 25; Available at http://www.thenation.com/article/youre-not-entitled.

- Human Rights Watch. No second chance: People with criminal records denied access to public housing. New York, NY: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi MY, London JA, Forge NG, Hickman L, Fain T, Riehman K. Elements of well-being affected by criminalizing the drug user. Public Health Reports. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S146–S150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Barth RP. From placement to prison: The path to adolescent incarceration from child welfare supervised foster or group care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2000;22(7):493–516. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Vlahov D, Freudenberg N. Primary care and health insurance among women released from New York City jails. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006;17(1):200–217. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legal Action Center. How to get Section 8 or public housing even with a criminal record: A guide for New York City Housing Authority Applicants and their advocates. New York, NY: Legal Action Center; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Levine HG, Small D. Marijuana arrest crusade racial bias and police policy in New York City 1997–2007. New York, NY: Civil Liberties Union; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Levitan M. Unemployment and joblessness in New York City, 2006: Recovery bypasses youth. New York, NY: Community Service Society of New York; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Levitan M. Out of school, out of work … out of luck? New York City’s disconnected youth. New York, NY: Community Service Society of New York; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren LM, Amodeo M, Chassler D. Mental health status, drug treatment use, and needle sharing among injection drug users. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(6):525–539. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.6.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald R, Marsh J. Disconnected youth? Journal of Youth Studies. 2001;4(4):373–391. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell M, Brookes L, Lurigio A, Baille D, Rodriguez P, Palanca P, Eisenberg S. Realizing the potential of national health care reform to reduce criminal justice expenditures and recidivism among jail populations (Community Oriented Correctional Health Care Issue Paper) Chicago, IL: Center for Health and Justice at TASC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mauer M. Race to incarcerate. New York, NY: New Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moore LD, Elkavich A. Who’s using and who’s doing time: Incarceration, the war on drugs, and public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(5):782–786. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SP, Teachman JD. Logistic regression: description, examples, and comparisons. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1988;50:929–936. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Education. Graduation rates class of 2007 (2003 cohort) New York, NY: City of New York; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Inmates in custody at least five days and released to NYC: Home residences. New York, NY: City of New York; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- New York State Division of Probation and Correctional Alternatives. Directory of alternatives to incarceration. New York, NY: Directory of Alternatives to Incarceration Programs in New York City; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pager D. The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108(5):937–975. [Google Scholar]

- Payne Y. A gangster and a gentleman. Men and Masculinities. 2006;8(3):288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(2):151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MT. Jail displacement for ATI programs. New York, NY: New York City Criminal Justice Agency; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Re-entry Policy Council. Report preview of Report of the Re-entry Policy Council: charting the safe and successful return of prisoners to the community. New York, NY: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Udry JR. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer S. Second chance from prison to school. New York Times. 2004 Jul 25;:B25. [Google Scholar]

- Roman CG, Travis J. Taking stock: Housing, homelessness, and prisoner reentry. New York, NY: Urban Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sheu M, Hogan J, Allsworth J, Stein M, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Flanigan T. Continuity of medical care and risk of incarceration in HIV-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. Journal of Womens Health. 2002;11(8):743–750. doi: 10.1089/15409990260363698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Exclusion Unit. Report of policy action team 12: Young people. London: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer E. The New York City Police Department’s “stop and frisk” practices: A report to the people of the state of New York from the Office of the Attorney General. Albany, NY: New York State Office of the Attorney General; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan ML. Getting paid: Youth crime and work in the inner cities. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson CB. Who graduates? Who doesn’t? A statistical portrait of public high-school graduation, Class of 2001. New York, NY: Urban Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taifa N, Beane TN. Integrative solutions to interrelated issues: A multidisciplinary look behind the cycle of incarceration. Harvard Law and Policy Review. 2009;3(2):283–306. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS, Byrne JM, Pattavina A. Racial disparity and the legitimacy of the criminal justice system: exploring consequences for deterrence. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and the Underserved. 2005;16(4 Suppl B):57–77. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend L, Flisher AJ, King G. A systematic review of the relationship between high school dropout and substance use. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10(4):295–317. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treschan L, Molnar C. Out of focus: A snapshot of public funding to reconnect youth to education and employment. New York, NY: Community Service Society of New York; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler J. The GED: Whom does it help? Results from a new approach to studying the economic benefits of the GED. Focus on Basics: Connecting Research and Practice. 1998 Available at http://www.ncsall.net/?id=771&pid=409.

- Vigil JD. A rainbow of gangs: Street cultures in the mega city. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. Deadly symbiosis: When ghetto and prison meet and mesh. Punishment & Society. 2001;3(1):95–134. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead T. Expressions of masculinity in a Jamaican sugartown: Implications for family planning. In: Whitehead T, Reid B, editors. Gender constructs and social issue. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press; 1992. pp. 103–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Young J. Vertigo in late modernity. London, UK: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]