Abstract

Background:

Schizophrenia is a devastating psychotic illness which is like the most mental disorders, shows complex inheritance; the transmission of the disorder most likely involves several genes and environmental factors. It is difficult to judge whether a particular person without schizophrenia has predisposing factors for the said disease. A few studies have shown the relative sensitivity and reliability of cognitive and psychophysiological markers of brain function as the susceptibility factors for schizophrenia which may aid us to find people with an increased risk of complex disorders like schizophrenia. The present work is an exploration on cognitive impairments in unaffected siblings of patients suffering from schizophrenia with a framework to explore why a mental disorder occurs in some families but not in others.

Materials and Methods:

This is a single point non-invasive study of non-affected full biological siblings of patients with schizophrenia, involving administration of a battery of neuropsychological tests to assess the cognitive function in the sibling group and a control group of volunteers with no history of psychiatric illness. The control group was matched for age, gender, and education. The siblings were also divided on the basis of the type of schizophrenia their siblings (index probands) were suffering from and their results compared with each other.

Results:

The siblings performed significantly poorly as compared to the controls on Wisconsin card sorting test (WCST), continuous performance test (CPT), and spatial working memory test (SWMT). The comparison between the sibling subgroups based on the type of schizophrenia in the index probands did not reveal any significant difference.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that there is a global impairment in the cognition of the non-affected siblings of patients of schizophrenia. Cognitive impairment might be one of the factors which will help us to hit upon people who are predisposed to develop schizophrenia in the future.

Keywords: Cognition, continuous performance test, schizophrenia, spatial working memory test, un-affected siblings, wisconsin card sorting test

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a devastating psychotic illness which has both fascinated and puzzled researchers and laymen for almost a hundred years. Eugene Bleuler (1911) coined the term “schizophrenia” and also described four primary symptoms of the disorder: Association disturbance, affective disturbance, ambivalence, and autism.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia is based on the clinical symptoms which are currently described in the classification systems as positive (delusions, hallucinations, thought form disorders, disorganization, and bizarre behaviours) and negative (psychomotor poverty, poverty of speech, and blunted affect). Recent studies are giving consideration to the cognitive functions of schizophrenia which include deficits in abstraction, verbal memory, vigilance, language, and executive functions.[1,2,3] Schizophrenia tends to run in families. Twin, family, and adoption studies of schizophrenia have demonstrated a substantial genetic component to the transmission of the disorder, but the nature of the genetic diathesis and the mode of inheritance remain to be identified. This genetic liability could be clinically unexpressed in some individuals at risk, as indicated by the study of offspring of twins discordant for schizophrenia.[4] A major consequence of this uncertainty is that it cannot be determined if a given individual without schizophrenia carries a predisposing genotype. Intensive investigations of biopsychobehavioral characteristics that mark the presence of genetic predisposition to the disorder are thus required to further identify individuals at increased risk for the development of schizophrenia. According to several vulnerability models, such identification is possible. According to the most of these models,[5] an accurate marker of schizophrenia vulnerability should detect ill, stabilized, or recovered patients with schizophrenia as well as unaffected individuals at a high risk for schizophrenia. It has an indisputable genetic basis, although there is still the absence of definitive genes, and the pathogenic molecular mechanisms remain unknown.

Schizophrenia, like most mental disorders, shows complex inheritance, the transmission of the disorder most likely involves several genes, and environmental factors that transmit the predisposition to the illness but not necessarily its expression. According to Egan and Goldberg, 2003,[6] using the trait like variables associated with the disorder as phenotypes in genetic studies might allow us to find the susceptibility genes of disorders influenced by multiple genes. The neurobiological measures related to the underlying molecular genetics of the illness such as biochemical, endocrinological, neurophysiological, neuroanatomical, or neuropsychological markers which involve the same biological pathways as the disorder but are closer to the relevant gene action than the categorical diagnosis are known as endophenotypes. These may aid us to find people with an increased risk of complex disorders like schizophrenia. A few studies have shown the relative sensitivity and reliability of cognitive and psychophysiological markers of brain function as the susceptibility factors for schizophrenia as compared to neuroanatomical or neurochemical factors.

The present work is an exploration on cognitive impairments in unaffected siblings of patients suffering from schizophrenia with a framework that is why a mental disorder occurs in some families but not in others.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The aims of the study were to assess neurocognitive functions in non-affected full biological siblings of patients with schizophrenia and to compare neurocognitive functions of these siblings with normal healthy controls (age, sex, and education matched).

This was a single point non-invasive study of non-affected full biological siblings of patients with schizophrenia, involving administration of a battery of neuropsychological tests to assess the cognitive function in the sibling group and a control group of volunteers with no history of psychiatric illness. The control group was matched for age, gender, and education. All subjects gave informed consent. The study was carried out from 1st September, 2005 to 1st August, 2006.

Sample consisted of non-affected full biological siblings of patients with schizophrenia, both new and follow-up cases from district Lucknow, attending the outpatient section of the Department of Psychiatry, C.S.M Medical University on specified days of the week. Siblings fulfilling the following selection criteria were taken up for the study.

The subjects were between the ages of 18-55 years and gave informed consent. The subject should have had at least 8 years of formal education, according to Indian Standards, and had no history of Bipolar Affective Disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Psychosis other than Schizophrenia in the family (clinically assessed for available siblings and on the basis of history for those not available). They must have scored 3 or less on General Health Questionnaire, 12 item version.[7]

Exclusion criteria for subjects included History of current or past psychiatric illness, history suggestive of significant physical disorder which can cause cognitive impairment such as: Seizures, cerebrovascular disorders, dementia, neurodegenerative disorders, systemic illness with known cerebral consequences, either presently or in past, significant head injury, current or past history of any substance abuse or dependence, current use of medications impairing cognition like tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-epileptics, benzodiazepines and lithium, and physical problems that would render study measure difficult or impossible to administer or interpret, e.g., blindness, hearing impairment, paralysis in upper limbs.

The members of the control group were selected from friends of the patients and from healthy volunteers fulfilling the following selection criteria. They were group matched with the sibling group for age, gender, and education.

On specified days in adult Psychiatry O.P.D. C.S.M.M.U. patients (old and new) diagnosed as a case of Schizophrenia from district Lucknow were screened for the availability of the siblings. The diagnosis of schizophrenia was ascertained on detailed clinical evaluation using ICD-10 DCR. The available unaffected siblings were ranked in the order of birth. One of the available siblings was randomly taken after applying the random number tables. Informed consent was taken and information regarding details of identification data, demographic profile, past history, negative history, family history, personal history, and physical examination was obtained on the semistructured proforma. General Health Questionnaire, 12 item version was applied and the sibling was then assessed in detail on the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) to rule out any psychopathology or psychiatric illness. Selection criteria were applied. If found eligible; he/she was included in the study. If not eligible the next available sibling was randomly taken after applying the random number tables and assessment for participation in the study was done after taking the informed consent. Computer based cognitive tests: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Continuous Performance Test (CST), and Spatial Working Memory Test (SWMT) were administered by an investigator on the same day of inclusion so as to avoid loss at follow up or on a mutually convenient day if the subject was not willing to be tested on the same day or if there were more than one sibling included on the same day. The same investigator applied the tests in both the sibling and the control groups. The investigator was aware of the status of the sibling/control group.

For controls, informed consent from healthy attendants (other than first degree relatives) of indoor patients was taken and they were group matched with the sibling group for age, gender, and education. General Health Questionnaire, 12 item version was applied and the subject was then assessed in detail on the SCAN to rule out any psychopathology or psychiatric illness. Selection criteria were applied. If found eligible; he/she was included in the study. Same tests as the sibling group were then applied to the control group on either the same day or on a mutually convenient day.

RESULTS

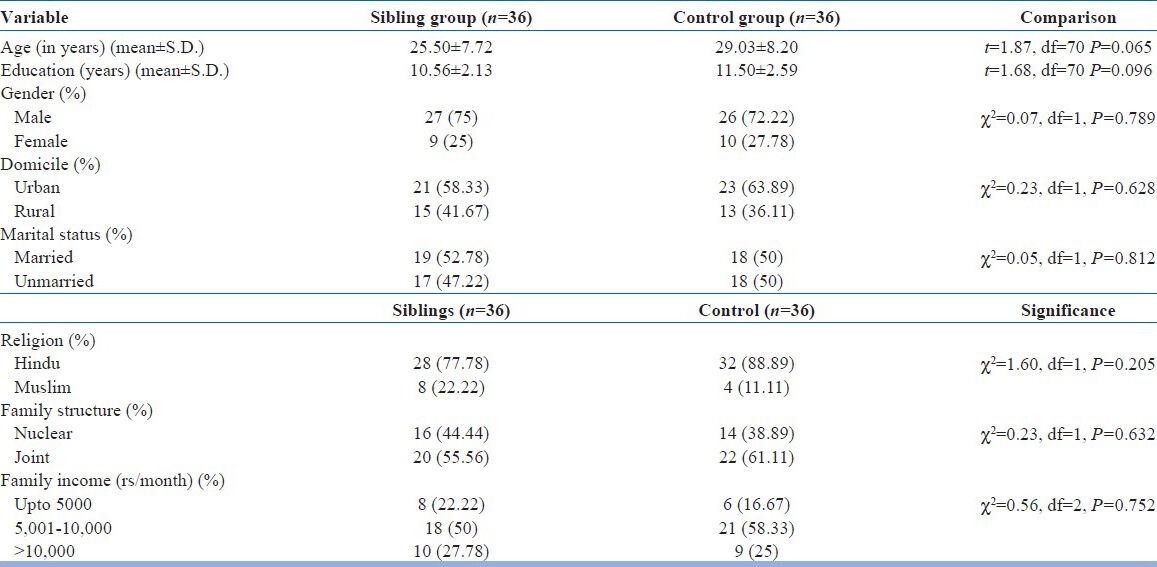

In this study a total of 120 patients of schizophrenia were screened for the presence of siblings. No siblings were available for 25 of these patients. Out of the siblings that were available, 43 fulfilled the selection criteria but 7 did not complete the assessment. A total of 50 controls were screened and 14 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Therefore, we had 36 siblings and control each. Table 1 shows the comparison of the sibling group and control group on various demographic parameters based on the parameters of age, gender, and education. In all the three parameters, the ‘P’ values were more than the significance limit (0.05) and thus the groups were not statistically different from each other on these parameters.

Table 1.

Comparison of sociodemographic variables (siblings and control group)

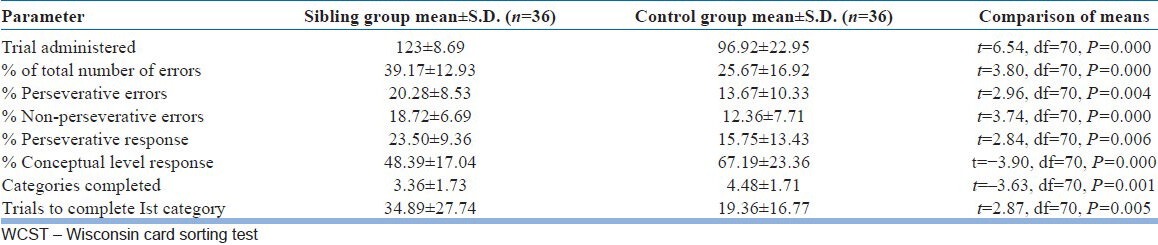

As shown in Table 2, the sibling group performed poorly as compared to the controls on all the parameters of WCST.

Table 2.

Comparison between siblings and controls on WCST

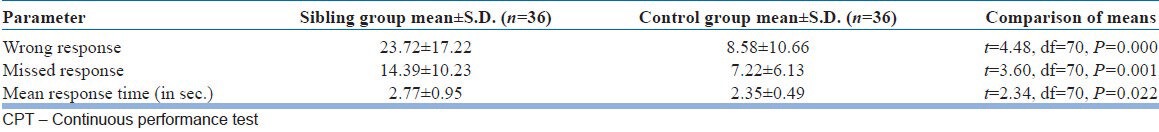

On CPT, the siblings had higher number of wrong and missed responses and greater response time as compared to the controls [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison between siblings and controls on CPT

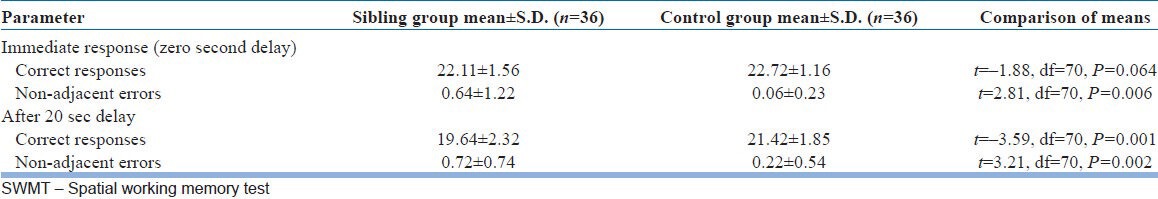

As shown in Table 4 on SWMT, as compared to the control group, the sibling group made statistically significant less correct responses at 20 second (P<0.01) and more non-adjacent errors at 0 seconds and after 20 seconds (P<0.01 each).

Table 4.

Comparison between siblings and controls on SWMT

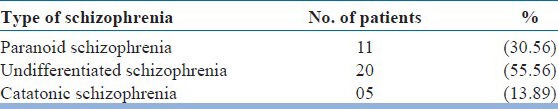

The siblings were then divided on the basis of the type of schizophrenia their siblings (index probands) were suffering from [Table 5]. The siblings of most of the subjects who were screened were suffering from undifferentiated schizophrenia (55.65%), whereas the rest were suffering from paranoid (30.56%) and catatonic (13.89%) schizophrenia.

Table 5.

Type of schizophrenia in index probands

The results of these groups on WCST, CPT, and SWMT were compared to each other. On WCST, the comparison of the results of siblings of different schizophrenia groups on the Trials administered (P=0.257), percentage of total errors (P=0.327), percentage of perseverative errors (P=0.146), percentage of non-perseverative errors (P=0.860), percentage of perseverative responses (P=0.115), percentage of conceptual level response (P=0.241), categories completed (P=0.054), and trials to complete 1st category (P=0.501) did not show any significant differences. On CPT, siblings from different groups performed comparably on the number of wrong responses (P=0.869), missed responses (0.746), and mean response time (0.374). The number of correct responses (P=0.435) and non-adjacent errors (P=0.672) on immediate response (zero second delay) in SWMT did not show any significant differences among the different types of schizophrenia. Similarly, correct responses (P=0.489) and non-adjacent errors (P=0.661) after 20 seconds delay in SWMT were similar among the different groups. No significant difference was found on any of the test amongst the siblings based on the type of schizophrenia in the index probands. Thus, the sibling group was taken to be a homogenous group with regard to the cognitive functions.

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to assess the neuro-cognitive functions in unaffected full biological siblings of patients with schizophrenia, and to compare them with that of an age, gender, and education matched normal control group. Patients and controls had to satisfy rigorous selection criteria for entering the study. The control group was selected from friends of patients and healthy volunteers. They were well matched for age, gender, and education status so that the confounding factors for assessment of cognitive functions and functional disability may be minimized. The matching also allowed the use of raw scores of tests like WCST. The selection criteria for controls were also kept as similar to the sibling group as possible, so that the differences in the cognitive functioning of the two groups could be attributed to genetic sharing between the unaffected sibling and the sibling suffering from schizophrenia. To avoid any bias on the socio-cultural grounds, the controls were mostly recruited from the friends of the patients.

Amongst the sibling group mean education was 10.56±2.13 years. Siblings educated for less than 13 years were 86.11% (31 out of 36) and 61.11% (22 out of 36) were educated for less than 11 years. Low mean years of education could be due to the fact that this hospital is a government hospital providing medical facilities at a low cost, thus most patients are less educated, from low socioeconomic status and rural background and also as a whole the literacy rates in India are lower than the western countries. As the study was conducted at only one center, these findings cannot be generalised.

Maximum numbers of patients were in the age group of 18-25 years (63.89%), with only two patients above the age of 45 years. This finding is in conformity with an occurrence of schizophrenia in a younger age group and these patients attending the psychiatry out-patient department. Age is associated with progressive decline in cognitive functions; age per se is a significant confounder for cognitive impairment.[8] Age factor could possibly confound the generalized cognitive deficits found in the study. However, the “younger” age sample in our study suggests that the deficits, if found, would be least affected by age associated cognitive impairment if at all.

The neurocognitive tests done in the study comprised of WCST, SWMT, and CPT. These tests were chosen because evidence has suggested differential impairment especially in cognitive domain related to frontal system, executive, and attention systems and medial temporal memory system. Moreover, these measures are important with regard to outcome. The computerized version of these test ensured greater reliability, objectivity, and standardization, less confrontational and formal approach. Moreover, it allowed the clinical assessors to have more time to focus on the patients rather than upon the presentation of the test material and data.

On the WCST the sibling group performed poorly when compared with healthy controls and that too statistically significantly. They made more number of errors which implies that they had more difficulty in understanding the concept of the test (P=0.000). Among the errors the siblings made significantly more number of non- perseverative errors (P=0.000), as well as, perseverative errors (P=0.004), which implies that either they were not interpreting the feedback properly or they were matching the cards without any concept in mind and also that they had difficulty in shifting between categories, although they were receiving the feedback to do so. The siblings made significantly less number of conceptual responses (P<0.000) further supporting the notion that their understanding of the test was poorer than the controls. The sibling group also took significantly more trials to complete the first category (P=0.005) indicating that the patients initially had more problem in understanding the test than the controls. Significant deficits were found in all the parameters which reveal a global deficit of executive functioning in the non-affected siblings of schizophrenia patients, thus suggesting that such siblings have difficulty in set shifting, in planning, problem solving, understanding of the problem, concept formation, and trial and error learning. These findings are represented clinically in the poor psychosocial functioning of the patients. Other studies of WCST in relatives[9,10,11,12] are consistent with our finding of increased perseveration scores in unaffected siblings compared to controls. In contrast, some studies have reported no significant differences between relatives and controls on WCST perseverative scores.[13,14,15] The sources of variation across studies may be due to sample and/or statistical variation. Thus, although our current findings are clear in suggesting that siblings of schizophrenia patients show increased WCST perseverative errors and therefore that this measure may be sensitive to the genetic liability to schizophrenia, our findings cannot be generalized due to small sample size.

It has been shown that tasks like WCST activate a neural network that includes important areas of brain such as dorsolateral region of prefrontal cortex.[1,16] These regions have numerous connections with the cortical systems involved in information processing. Poor WCST performance that is well known in schizophrenia is thought to reflect prefrontal cortical dysfunction.[17,18] So, as previously suggested by others,[19,20] the observation of poor WCST performance in the sibling group could implicate similar prefrontal dysfunction.

In our study, on the test for attention, vigilance and concentration abilities – the CPT, the sibling group made significantly more wrong responses, i.e., the errors of commission (P=0.000), more missed response, i.e., errors of omission (P=0.001) and showed a significantly slower response (P=0.022) than the control group. The findings of previous studies of attention in siblings of patients with schizophrenia have been mixed. The largest such study, that of Chen et al. 1998,[21] found significant group differences, as have several others.[22,23] On the other hand, many[24,25] have found differences only with more difficult versions of the CPT. The frontal and the cingulate cortex are crucial for the activity of generating internal cues for initiating, planning, and monitoring behavioral responses, the basal ganglia, in turn, are partly responsible for the gating mechanisms of both inner and external sensory input. Although only a few studies have studied this, the results have shown abnormalities expressed as exaggerated functioning in the prefrontal cortex,[26] or reductions in this functioning.[27] Another study[28] supported the view that functioning of the thalamic nuclei was increased compared with control subjects during a working memory task. The exaggerated activation may reflect the reduced thalamic volume that has been observed in relatives with schizophrenia patients.[29]

The sibling group performed significantly worse than control group on SWMT involving visual memory for prior actions. The performance was significantly poor on the pattern recognition test as compared to control subjects at zero second delay, as shown by the significantly more non-adjacent errors (P=0.006) committed by the sibling group at zero second delay. The correct responses were significantly less in the patient group after 20 s delay, but not at zero second delay. Significant deficits were found in the ability to recognize the spatial locations of a set of stimuli reported after a delay of 20 s; both in the correct responses (P=0.001) and nonadjacent errors (P<0.002). The findings match most of the previous studies.[30,31]

The deficits in spatial working memory in sibling group as suggested by the study, point toward the involvement of dorsal and ventral streams of neural connections originating at posterior regions. Significant hypoactivation has been found in schizophrenia patients particularly in the right hemisphere, in the dorsolateral frontal, and temporal regions and in the inferior parietal, and subcortically in the thalamus.[32]

On comparing the sibling groups based on the type of schizophrenia in the index probands, our study did not show any significant difference in the cognitive functioning between the three groups. However, some studies have shown contrasting results from our study. Auslander et al., 2002,[33] reported greater impairment of cognition in non-paranoid group when assessed for disturbed thinking and cognition using Ego Impairment Index (EII) in older paranoid and non-paranoid schizophrenia patients. Similarly, Patrick et al., 1990[34] in a study reported that paranoid schizophrenics performed within the same range as normal on cue recognition whereas non-paranoid schizophrenic adults performed significantly below normal controls on cue recognition and suggested these findings to have relevance for understanding the attention deficit in social situations seen in patients with schizophrenia.

The results of the study should be interpreted in view of the following limitations. Due to the constraints of a time bound study and because of the stringent selection criteria, the sample size was small and hence the results are subjected to Type II error. The study is a cross-sectional study, to further clarify the state trait controversy longitudinal studies are needed. The study involved a single investigator who was not blind to the status of the participant, however, the test was done on a computer and the investigator had no active role in conducting or evaluating the results of the tests.

The sample of unaffected siblings was relatively small and may represent a biased proportion of the sibling population (it might have been the case that ‘healthy’, high-functioning siblings could not participate). Moreover, although the subjects for the study project were randomly selected and carefully evaluated, they mainly came from families which attended our outpatient clinic and therefore represent only the part of all schizophrenia cases, making it difficult to apply results to generalized population.

Relatives share environments as well as genes. Thus, any deficits observed may reflect shared genetic or environmental effects. Although there is little evidence for shared environmental effects in schizophrenia in general, such effects could not be completely ruled out. It is possible that modelling with factors of bias potential (e.g., shared deviant rearing environment or gene-environmental interaction) would have given different results and in part explains those features that were assumed to be genetically inherited.

Despite the above limitations the present study has few strengths when compared to many other studies in this area. Many confounding factors such as age, gender, significant physical illness, psychiatric conditions, substance use, and medication affecting cognition (e.g., benzodiazepines) were taken care of thus enabling the maximum attribution of the results to genetic sharing between the sibling and the index proband. The computerized version of these test were an added advantage as they ensured greater reliability, objectivity and standardization, less confrontational, and formal approach. Moreover, it allowed the clinical assessors to have more time to focus on the patients rather than upon the presentation of the test material and data.

Our inclusion of only adult siblings as first degree relatives for assessment offers advantages[19] as compared to children at high risk study or including parents of those suffering from schizophrenia because adults may have already reached the peak age of risk for schizophrenia, having a parent with schizophrenia, might interfere more with cognitive development than having a sibling with schizophrenia, age-linked stratification bias is reduced. Our siblings will not be affected by general decline in cognition seen with age which would have been the case if parents of those who are suffering from schizophrenia would have been included.

Future studies should focus on finding out specific neurological deficits as endophenotypes so that those at risk of developing schizophrenia could be identified early before the onset of illness. Studies should also focus on correlating these deficits with structural changes in the brain of these individuals at risk. Studies are also required to comment, whether optimizing the prophylactic pharmacological treatment and psycho education might reduce cognitive impairment, and whether it could be possible to reduce the risk of schizophrenia in those at risk. Further studies also required if siblings would benefit from neuropsychological rehabilitation in order to reduce the impact of cognitive impairment in their overall functioning.

CONCLUSION

Our study revealed that the siblings of patients of schizophrenia performed poorly as compared to the controls, which is in keeping with the findings of previous studies. No significant differences were found in the cognitive performance of siblings of index cases suffering from different types of schizophrenia. However, these findings must be corroborated by further studies in future possibly with a greater sample size so that these findings could be applied to the general public.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Cizadlo T, Arndt S, Rezai K, Ponto LL. Schizophrenia and cognitive dysmetria: A positron-emission tomography study of dysfunctional prefrontalthalamic- cerebellar circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9985–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braff DL. Information processing and attention dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19:233–59. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green MF, Kern PS, Braff DL, Minz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull. 2000;19:797–804. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottesman II, Bertelsen A. Confirming unexpressed genotypes for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:867–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810100009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spring B, Zubin J. Attention and information processing as indicators of vulnerability to schizophrenic episodes. J Psychiatr Res. 1978;14:289–302. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(78)90033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan MF, Goldberg TE. Intermediate cognitive phenotypes associated with schizophrenia. Methods Mol Med. 2003;77:163–97. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-348-8:163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg D, McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 2nd ed. Vol. 181. New York: Oxford U Pr; 1972. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), 12 item version, 20 item version, 30 item version, 60 item version [GHQ12, GHQ20, GHQ30, GHQ60] pp. 225–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorm AF. Cognitive deficit in the depressed elderly: A review of some basic unresolved issues. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1986;20:11–22. doi: 10.3109/00048678609158860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke P, Maier W, Hain C, Klinger T. Wisconsin card sorting test: An indicator of vulnerability to schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 1992;6:243–9. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90007-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toomey R, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Pepple JR, Tsuang MT. Association of neuropsychological vulnerability markers in relatives of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 1998;31:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saoud M, d’Amato T, Gutknecht C, Triboulet P, Bertaud JP, Marie-Cardine M, et al. Neuropsychological deficit in siblings discordant for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:893–902. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Gscheidle T, Weirich M, Rawlings R, Hyde TM, et al. Relative risk for cognitive impairments in siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ismail B, Cantor-Graae E, McNeil TF. Minor physical anomalies in schizophrenia: Cognitive, neurological and other clinical correlates. J Psychiatry Res. 2000;34:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(99)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurent A, Biloa-Tang M, Bougerol T, Duly D, Anchisi AM, Bosson JL, et al. Executive/attentional performance and measures of schizotypy in patients with schizophrenia and in their nonpsychotic first-degree relatives. Schizophr Res. 2000;46:269–83. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keri S, Kelemen O, Benedek G, Janka Z. Different trait markers for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A neurocognitive approach. Psychol Med. 2001;31:915–22. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milner B. Effects on different brain lesions on card sorting: The role of the frontal lobes. Arch Neurol. 1963;9:90–100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Pliskin NH, Podd MH. Further evidence for dementia of the prefrontal type in schizophrenia? A controlled study of teaching the WCST. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:1008–14. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800230088014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berman KF, Illowsky BP, Weinberger DR. Physiological dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: IV. Further evidence for regional and behavioral specificity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:616–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800310020002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Pepple JR, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV. Neuropsychological risk indicators for schizophrenia: A review of family studies. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:103–19. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sautter FJ, McDermott BE, Cornwell J, Black FW, Borges A, Johnson J, et al. Patterns of neuropsychological deficit in cases of schizophrenia spectrum disorder with and without a family history of psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 1994;54:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen WJ, Liu SK, Chang CJ, Lien YJ, Chang YH, Hwu HG. Sustained attention deficit and schizotypal personality features in nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1214–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.9.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelstein JR, Cannon TD, Gur RE, Gur RC, Moberg P. Attentional dysfunctions in neuroleptic-naive and neuroleptic-withdrawn schizophrenic patients and their siblings. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:203–12. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cannon TD, Zorrilla LE, Shtasel D, Gur RE, Gur RC, Marco EJ, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in siblings discordant for schizophrenia and healthy volunteers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:651–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950080063009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornblatt BA, Keilp JG. Impaired attention, genetics, and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:31–46. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nuechterlein KH. Vigilance in schizophrenia and related disorders. In: Steinhauer SR, Gruzelier JH, Zubin J, editors. Neuropsychology, Psychophysiology and Information Processing. Vol. 5. New York: Elsevier; 1991. pp. 397–433. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callicott JH, Egan MF, Mattay VS, Bertolino A, Bone AD, Verchinksi B. Abnormal fMRI response of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in cognitively intact siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:709–19. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keshavan MS, Dick E, Mankowski I, Harenski K, Montrose DM, Diwadkar V, et al. Decreased left amygdala and hippocampal volumes in young offspring at risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;58:173–83. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thermenos HW, Seidman LJ, Breiter H, Goldstein JM, Goodman JM, Poldrack R, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging during auditory verbal working memory in nonpsychotic relatives of persons with schizophrenia: A pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Goldstein JM, Goodman JM, Kremen WS, Toomey R, et al. Thalamic and amygdala-hippocampal volume reductions in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia: An MRI-based morphometric analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:941–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith CW, Park S, Cornblatt B. Spatial working memory deficits in adolescents at clinical high risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;81:211–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diwadkar VA, Sweeney JA, Boarts D, Montrose DM, Keshavan MS. Oculomotor delayed response abnormalities in young offsprings and siblings at risk for schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2001;6:899–903. doi: 10.1017/s109285290000095x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salgado-Pineda P, Junque C, Vendrell P, Baeza I, Bargallo N, Falcon C, et al. Decreased cerebral activation during CPT performance: Structural and functional deficits in schizophrenic patients. Neuroimage. 2004;21:840–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auslander L, Perry W, Jeste DV. Assessing disturbed thinking and cognition using the Ego Impairment Index in older schizophrenia patients: Paranoid vs. nonparanoid distinction. Schizophr Res. 2002;53:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corrigan PW, Ruth M, Davies-Farmer, Melinda R. Stolley social cue recognition in schizophrenia under variable levels of arousal. Cognit Ther Res. 1990;14:353–61. [Google Scholar]