Abstract

Background/Aims

We compared the cirrhosis-prediction accuracy of an ultrasonographic scoring system (USSS) combining six representative sonographic indices with that of liver stiffness measurement (LSM) by transient elastography, and prospectively investigated the correlation between the USSS score and LSM in predicting cirrhosis.

Methods

Two hundred and thirty patients with chronic liver diseases (187 men, 43 women; age, 50.4±9.5 y, mean±SD) were enrolled in this prospective study. The USSS produces a combined score for nodularity of the liver surface and edge, parenchyma echogenicity, presence of right-lobe atrophy, spleen size, splenic vein diameter, and abnormality of the hepatic vein waveform. The correlations of the USSS score and LSM with that of a pathological liver biopsy (METAVIR scoring system: F0-F4) were evaluated.

Results

The mean USSS score and LSM were 7.2 and 38.0 kPa, respectively, in patients with histologically overt cirrhosis (F4, P=0.017) and 4.3 and 22.1 kPa in patients with fibrotic change without overt cirrhosis (F0-F3) (P=0.025). The areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the USSS score and LSM for F4 patients were 0.849 and 0.729, respectively. On the basis of ROC curves, criteria of USSS ≥6: LSM ≥17.4 had a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of 89.2%:77.6%, 69.4%:61.4%, 86.5%:83.7%, 74.6%:51.9% and 0.83:0.73, respectively, in predicting F4.

Conclusions

The results indicate that this USSS has comparable efficacy to LSM in the diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Elastography, Cirrhosis, Biopsy

INTRODUCTION

Cirrhosis is a liver disease in which the hepatic architecture is destroyed, with fibrous septa surrounding regenerated or regenerating parenchymal nodules. Pathological examination of percutaneous biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing the extent of fibrosis and the progression of cirrhosis.1,2 Although percutaneous liver biopsy (LB) is relatively safe, it is characterized by significant morbidity (3%) and mortality (0.03%).3 In addition, examination of LB may result in false negative findings due to inadequate liver samples.

Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) by transient elastography (TE) generates an elastic wave using a vibration delivered to the right lobe of the liver through intercostal spaces and measures the propagation velocity of the elastic shear wave in the tissue, which is directly related to liver stiffness.4 This method was first developed to evaluate chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients in France. Recently, LSM has been successfully used for the assessment of fibrosis in other chronic liver diseases.4-12 Currently, although controversies still remain, LSM by TE seems to be a promising non-invasive method to estimate liver fibrosis.5,6,13

Ultrasonography (US) has been widely used for several decades in the diagnosis of cirrhosis.14-23 Many attempts to assess hepatic fibrosis using US features have been made, with the aim of replacing the invasive diagnosis of cirrhosis. In a study by Lu et al, US examination indicated that the thickness of the liver capsule, maximum oblique diameter of the right liver, diameter of the splenic vein, and thickness of the spleen were correlated with the staging of liver fibrosis. While the use of isolated US factors lacks accuracy and reliability, the combination of multiple US features was quite sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis.24 Therefore, we developed an ultrasonographic scoring system (USSS) composed of 6 US features: liver surface and edge nodularity, parenchyma echogenicity, presence of right lobe atrophy, spleen size, splenic vein diameter, and abnormality of hepatic waveform.

In terms of their accuracy and reproducibility, both LSM and US have high potential as non-invasive techniques for the evaluation of fibrosis in chronic liver disease (CLD) patients.4 However, no comparison study between US and LSM has been performed to evaluate their usefulness in predicting cirrhosis.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

From October 2007 to February 2011, a total of 230 patients admitted to the Wonju College of Medicine University Hospital with CLD who underwent LB were included in this study. The following features were prospectively measured and analyzed: age, sex, height, weight, etiology of cirrhosis, Child class, albumin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time, platelet count, LSM by TE, and 6 US features (liver surface and edge nodularity, parenchyma echogenicity, right lobe atrophy, spleen size, splenic vein diameter, and hepatic vein waveform). All patients were studied using the 2 non-invasive methods: TE (Fibroscan; Echosens, Paris, France) with a 3.5-MHz M probe and US (Prosound α10; Aloka, Tokyo, Japan) with a 3.5-MHz convex probe.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the hospital approved the protocol, and written informed consent to participate in the study was received from all participating patients. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in Edinburgh 2000).

Methods

Ultrasonographic scoring system

The USSS is composed of 6 US features (Table 1) that have been reported to demonstrate associations with the presence of cirrhosis and are currently utilized in clinical practice: liver surface and edge nodularity, parenchyma echogenicity, presence of right lobe atrophy, spleen size, splenic vein diameter, and abnormality of hepatic vein waveform. A single operator (S.K.B) performed the ultrasound examination to determine the USSS.

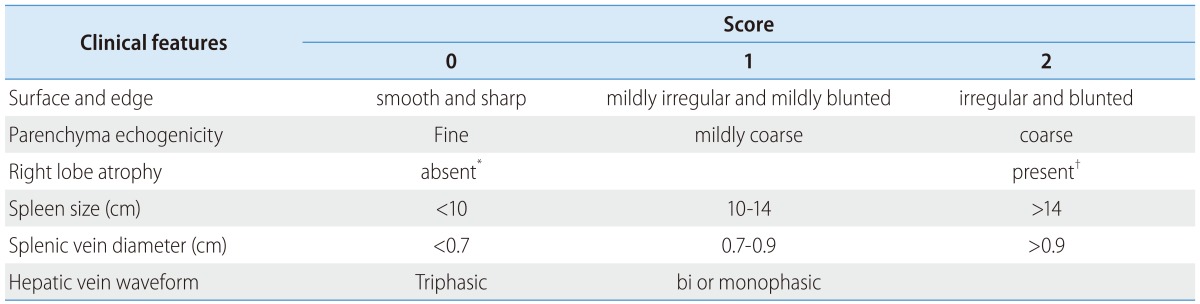

Table 1.

Ultrasonographic and Doppler features used to evaluate liver cirrhosis

The total score from six ultrasonographic indices including surface nodularity and edge shape (0-2), parenchyma echogenicity (0-2), right lobe atrophy (0-2), spleen size (0-2), splenic vein diameter (0-2) and hepatic vein waveform (0-1) was calculated.

*Right lobe maximal oblique diameter >7 cm with no subphrenic ascites.

†Right lobe maximal oblique diameter <10 cm with subphrenic ascites.

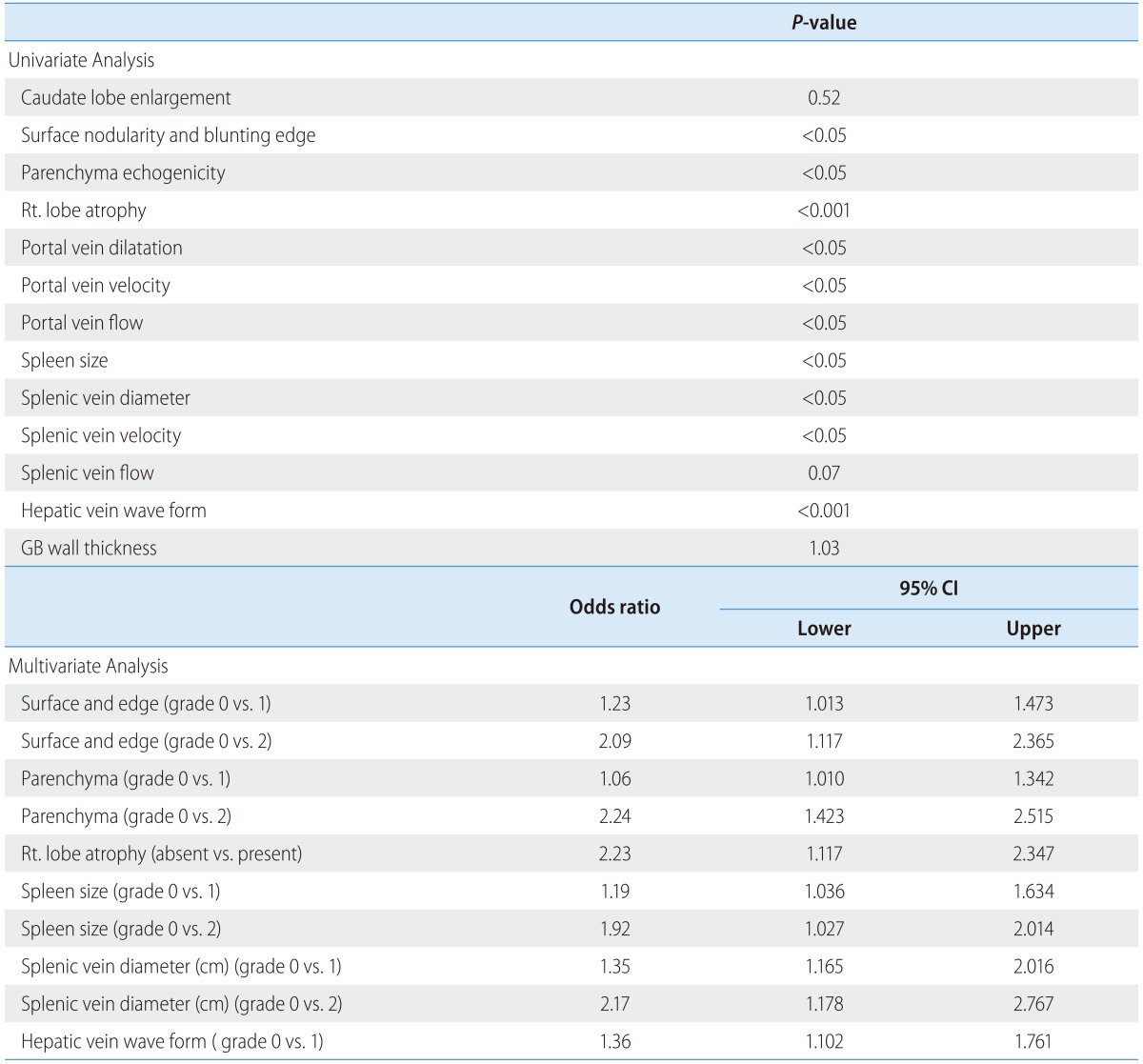

Because combined USSS has not been utilized widely in previous studies, no gold standard has been established for the selection of features to include in the USSS. Therefore, we measured 13 US features and analyzed the relationship between each feature and the degree of hepatic fibrosis. As shown in Table 2, 10 features demonstrated statistical significance levels of P<0.05 in univariate analysis and 3 features (caudate lobe enlargement, splenic vein flow and gallbladder thickness) were nonsignificant statistically. A multivariate analysis for ultrasonographic features associated with cirrhosis was then conducted using binary logistic regression analysis. The factors with P<0.1 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, 6 representative sonographic features ultimately demonstrated statistical significance. We used the odds ratio resulting from multivariate analysis to weight the features in the scoring system.

Table 2.

Results of uni- and multivariate analyses for the ultrasonographic features related to cirrhosis

A multivariate analysis for ultrasonographic features associated with cirrhosis was conducted using binary logistic regression analysis. The factors with P<0.1 in univariate analyses were included in multivariate analysis using enter method.

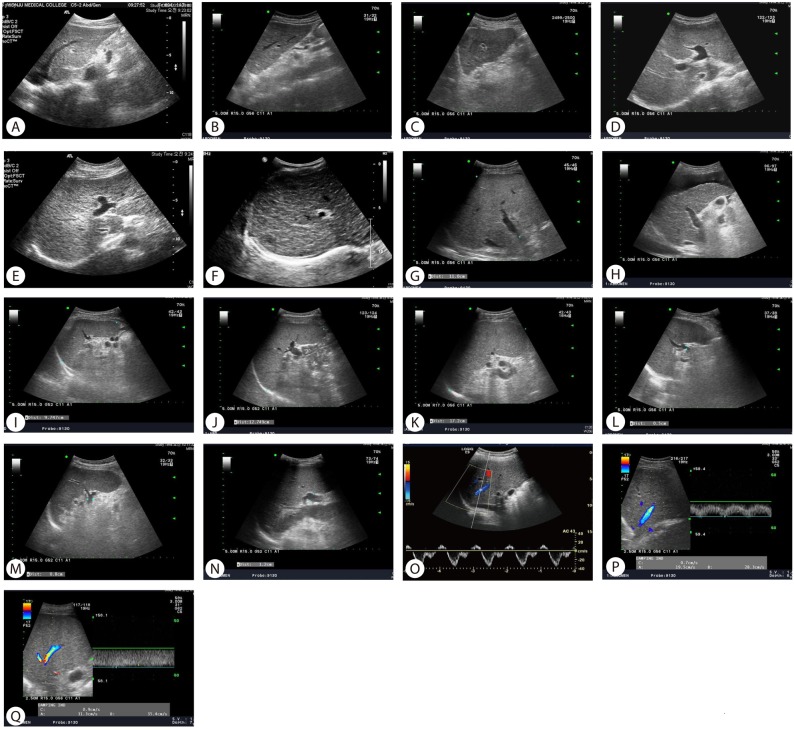

The measurement and evaluation of the features was performed in accordance with methods described in the literature,14,15,17,19-24 which were scored according to the following criteria. Surface and edge were distinguished as smooth surface and sharp edge (=0), mild uneven or waveform surface and mildly blunted edge (=1), and undulated or irregular nodular surface and blunted edge (=2). Parenchyma was classified as homogeneous appearance (=0), heterogeneous appearance with fine scattered hypoechoic and hyperechoic areas (=1), and coarse irregular pattern (=2). Right lobe atrophy was considered absent (=0) when maximal oblique diameter was larger than 7 cm with no subphrenic ascites and present (=2) when less than 10 cm with subphrenic ascites. Spleen size was calculated from the craniocaudal maximal length and considered normal (=0) when less than 10 cm, mild splenomegaly (=1) between 10 and 14 cm, and splenomegaly (=2) when larger than 14 cm. Splenic vein diameter was measured as the largest antero-posterior diameter and considered normal (=0) when less than 0.7 cm, mildly dilated (=1) when between 0.7 cm and 0.9 cm, and frankly dilated (=2) when larger than 0.9 cm. Hepatic vein waveform was considered normal (=0) when triphasic and abnormal (=1) when bi- or monophasic. Ultrasonographic images of representative patients are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography images showing representative cases of ultrasonographic scoring system (USSS) parameters. (A) smooth and sharp surface and edge, score 0; (B) mildly irregular and mildly blunted surface and edge, score 1; (C) irregular and blunted surface and edge, score 2; (D) fine parenchyma, score 0; (E) mildly coarse parenchyma, score 1; (F) coarse parenchyma, score 2; (G) absence of right lobe atrophy (right lobe maximal oblique diameter >7 cm with no subphrenic ascites), score 0; (H) presence of right-lobe atrophy (right-lobe maximal oblique diameter <10 cm with subphrenic ascites), score 2; (I) spleen size <10 cm, score 0; (J) spleen size 10-14 cm, score 1; (K) spleen size >14 cm, score 2; (L) splenic vein diameter <0.7 cm, score 0; (M) splenic vein diameter 0.7-0.9 cm, score 1; (N) splenic vein diameter >0.9 cm, score 2; (O) triphasic hepatic vein waveform, score 0; (P) biphasic hepatic vein waveform, score 1; (Q) monophasic hepatic vein waveform, score 1.

Liver stiffness measurement

TE measures the liver stiffness in a volume that approximates a cylinder 1 cm wide and 4 cm long, and the results were expressed in kilopascals (kPa). The technique was performed by 2 operators (K.M.M. and M.Y.K.) with 4 years experience performing LSM by TE with a 3.5-MHz M probe and trained for proficiency by the manufacturer (Echosens, Seoul, Korea), who were blinded to the USSS results. At least 10 measurements were carried out in each patient. Measurements were performed on the right lobe of the liver through the intercostal spaces between 25 and 65 mm from the skin surface, with patients lying in the dorsal decubitus position with the right arm in maximal abduction. The median value (expressed in kPa) was considered as representative of the liver elastic modules.

Reproducibility and inter-operator variability of USSS and LSM

To assess the reproducibility of this method, one operator (M.Y.K) evaluated day-to-day variability with repeated studies of both USSS and LSM in 10 healthy volunteers over 5 consecutive days by obtaining coefficients of variation (calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the mean and multiplying by 100). Thus, higher reproducibility is associated with a lower coefficient of variation. The inter-operator variability between the 2 operators (K.M.M. and M.Y.K.) for determining both USSS and LSM, expressed as a kappa value, was analyzed in 10 healthy volunteers.

Histological examination

All biopsy specimens were analyzed independently by an experienced hepatopathologist (M.Y.C.) who was blinded to patients' clinical data including USSS, LSM, and clinical data. LB specimens were fixed in formalin and paraffin embedded. Four-micrometer-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson trichrome. LB specimens unsuitable for fibrosis assessment (LB length <15 mm or less than 6 portal tracts) were excluded from analysis. LSM and USSS were performed on the same day. LB was performed within 1 day after USSS and LSM.

Histological fibrosis scores of the liver are a mixture of descriptions of fibrotic and architectural histological changes. We classified LB specimens into 5 categories with the application of the METAVIR scoring system: lack of fibrosis (F0), portal fibrosis (F1), periportal fibrosis (F2), bridging fibrosis (F3), and cirrhosis (F4).25 The patient population was then divided into 2 groups: fibrotic change without cirrhosis (F0-3) and histologically overt cirrhosis (F4).

Statistical analysis

A multivariate analysis for ultrasonographic features associated with cirrhosis was conducted using binary logistic regression analysis. The factors with P<0.1 in univariate analyses were included in multivariate analysis using enter method.

Results are expressed as mean±standard deviation. Comparisons between clinical features, USSS, laboratory tests, and histological outcome (absence or presence of cirrhosis) were analyzed by the independent-samples t test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves of LSM and USSS for F4 cases were generated. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used for the correlation analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 18.0, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

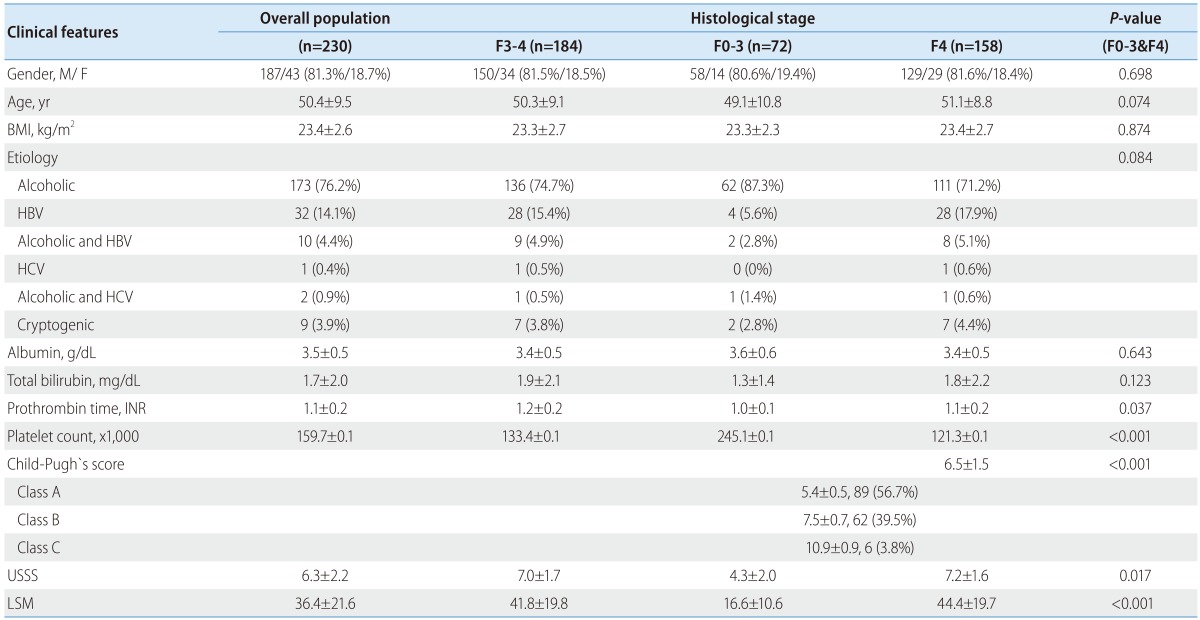

The general characteristics of study populations are summarized in Table 3. The mean age of participants (187 men and 43 women) was 50.4±9.5 years. Seventy-two patients (21.4%) demonstrated histologically no overt cirrhosis (F0-3), and 158 (78.6%) patients had fibrotic change with overt cirrhosis (F4). Sex, age, body mass index (BMI), etiology, albumin, and total bilirubin did not significantly differ between the 2 groups (all P>0.05), but statistically significant differences were observed in USSS, LSM, prothrombin time, and platelet count (P<0.05).

Table 3.

General characteristics of the 230 study patients

Values are expressed as meas±standard deviation or number. P<0.05 is denoted in bold. F3-4, advanced fibrosis; F0-3, fibrotic change without overt cirrhosis; F4, overt cirrhosis; BMI, body mass index; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; USSS, ultrasonographic scoring system; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; INR, international normalized ratio.

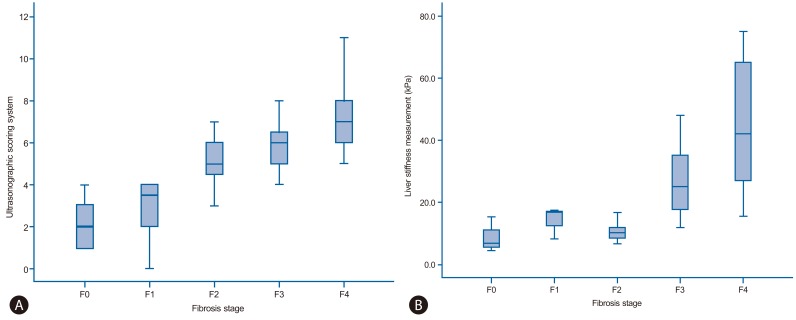

Fourteen patients (6.1%) were classified as F0 fibrosis stage (without fibrosis), 12 (5.2%) as F1, 20 (8.7%) as F2, 26 (11.3%) as F3, and 158 (68.7%) as F4. One hundred eighty-four patients (80.0%) demonstrated fibrosis stage ≥ F3 (advanced fibrosis). The median USSS and LSM (kPa) were 3.0 and 6.8 for patients with F0 fibrosis, 3.5 and 16.6 for F1, 5.0 and 9.9 for F2, 6.0 and 25.1 for F3, and 7.0 and 42.2 for F4, respectively (Fig. 2-A and -B). In addition, both USSS and LSM demonstrated significant positive correlations with the histological grade of fibrosis (P<0.001). Pearson's correlation coefficient for USSS and LSM was r=0.432 (P<0.001).

Figure 2.

(A) USSS score for each fibrosis stage. The top and bottom edges of the boxes indicate the first and third quartiles, respectively, while the lines through the middle of the boxes indicate median values. The median USSS scores were 2.0 (range, 1-4), 3.5 (range, 0-4), 5.0 (range, 2-7), 6.0 (range, 4-9), and 7.0 (range, 5-11) in fibrosis stages F0-F4, respectively. (B) Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) values for each fibrosis stage. The median LSM values were 6.8 (range, 4.4-15.3), 16.6 (range, 8.2-17.3), 9.9 (range, 6.6-16.6), 25.1 (range, 11.8-48.0), and 42.2 (range, 15.5-75.0) kPa in F0-F4, respectively.

Reproducibility and inter-operator variability of USSS and LSM

In 10 healthy control subjects, the coefficients of variation of USSS and LSM were 7% and 8%, respectively. The kappa values of USSS and LSM were calculated as 0.85 and 0.83, respectively, indicating excellent reproducibility and concordance between the 2 operators.

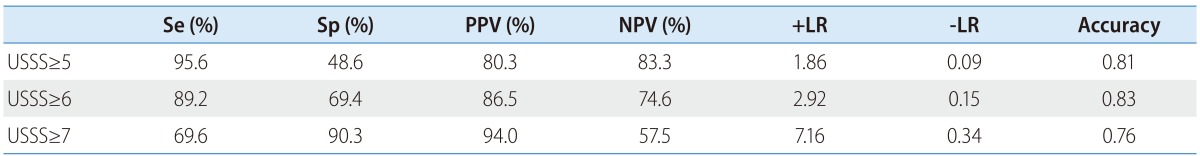

Correlation between USSS and histological grade of overt cirrhosis (F4)

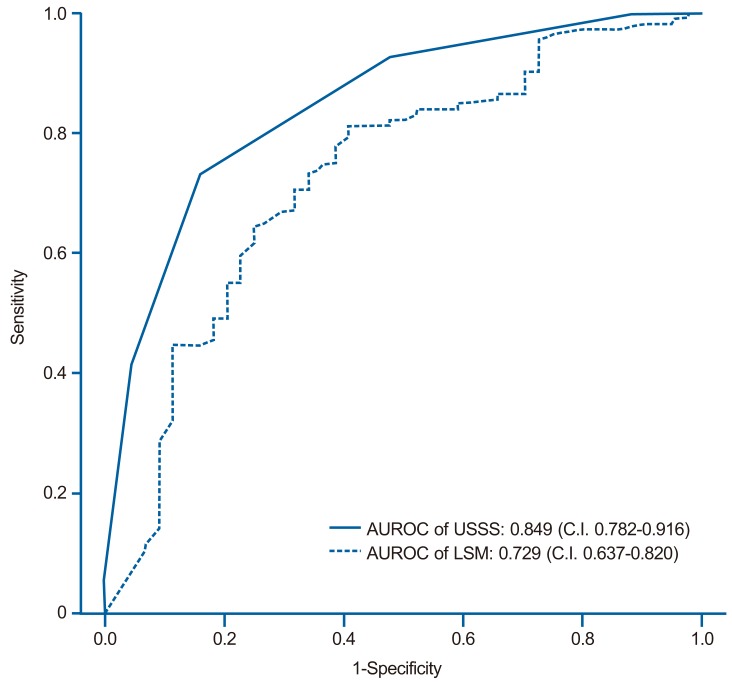

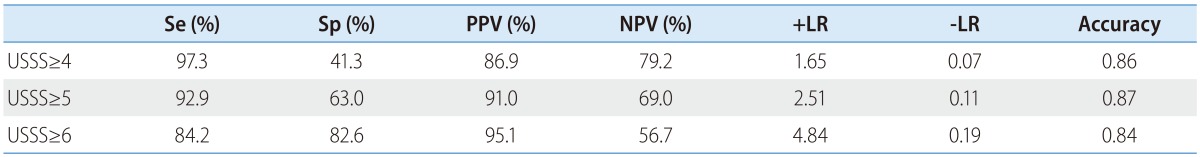

The mean USSS scores±SD of F0-3 and F4 patients were 4.3±2.0 and 7.2±1.6, respectively (P=0.017). In the prediction of overt cirrhosis (F4), area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AUROC) was 0.849 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.782-0.916) (Fig. 3). Based on the ROC curve, different cut-off values for USSS were determined. USSS ≥6 had sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), +likelihood ratio (LR), -LR, and accuracy of 89.2%, 69.4%, 86.5%, 74.6%, 2.92, 0.15, and 0.83, respectively, in predicting F4. Table 4 summarizes the best results for PPV, NPV, +LR, and -LR at different USSS cut-off values. Twenty-two (9.6%) of 163 patients with USSS above 6 or more had fibrotic change without overt cirrhosis (F0-3).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) Curves Of The Usss Score And Lsm For The Prediction Of Overt Fibrosis (F4). The Areas Under The Roc Curves Of The Usss Score And Lsm Were 0.849 (Standard Error, 0.001; 95% Confidence Interval, 0.782-0.916) And 0.729 (Standard Error, 0.001; 95% Confidence Interval, 0.637-0.820), respectively.

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy of the ultrasonographic scoring system (USSS) for the histological grade of overt cirrhosis (stage F4)

Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; +LR, positive likelihood ratio; -LR, negative likelihood ratio; USSS, ultrasonographic scoring system.

Correlation between LSM and histological grade of overt cirrhosis (F4)

The mean LSM values±SD of the F0-3 and F4 patients were 22.1±19.5 kPa and 38.0±22.3 kPa, respectively (P=0.025). In the prediction of overt cirrhosis (F4), AUROC was 0.729 (95% CI 0.637-0.820) (Fig. 3). Based on the ROC curve, different cut-off values for LSM were determined. LSM ≥17.4 had a Se, Sp, PPV, NPV, +LR, -LR, and accuracy of 77.6%, 61.4%, 83.7%, 51.9%, 2.01, 0.36, and 0.73, respectively, in predicting F4.

Correlation between USSS and histological grade of advanced fibrosis (F3-4)

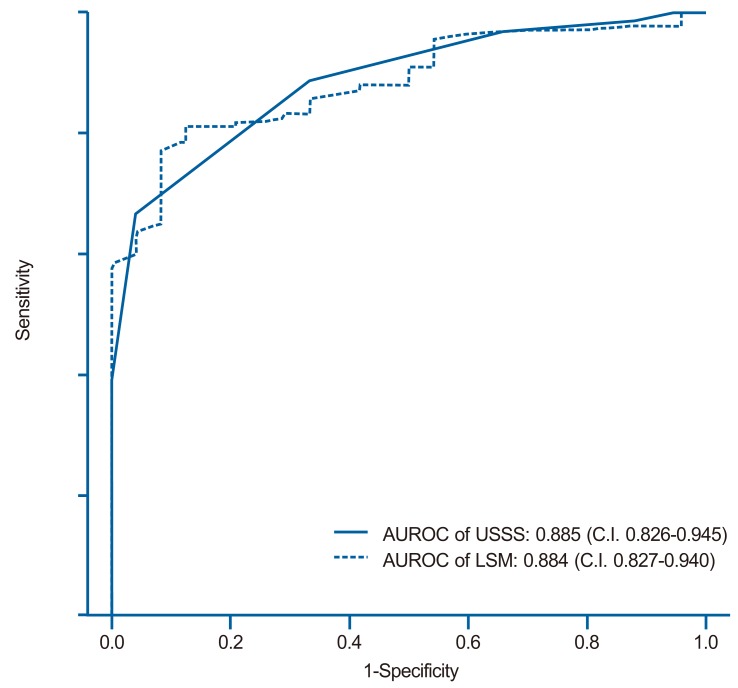

The mean USSS scores±SD of F0-2 and F3-4 patients were 3.6±1.9 (n=46, 11.5%) and 7.0±1.7 (n=184, 88.5%), respectively (P=0.090). In the prediction of advanced fibrosis (F3-4), AUROC was 0.885 (95% CI 0.826-0.945) (Fig. 4). Based on the ROC curve, different cut-off values for USSS were determined. USSS ≥5 had Se, Sp, PPV, NPV, +LR, -LR, and accuracy of 92.9%, 63.0%, 91.0%, 69.0%, 2.51, 0.11, and 0.87, respectively, for the prediction of F3-4. Table 5 summarizes the results for PPV, NPV, +LR, and -LR at different USSS cut-off values. Seventeen (9.0%) of 188 patients with USSS above 5 were F0-2.

Figure 4.

ROC curves of the USSS score and LSM for the prediction of advanced fibrosis (F3 or F4). The areas under the ROC curves of the USSS score and LSM were 0.885 (standard error, 0.001; 95% confidence interval, 0.826-0.945) and 0.884 (standard error, 0.001; 95% confidence interval 0.827-0.940), respectively.

Table 5.

Diagnostic accuracy of the USSS for advanced fibrosis (stage F3 or F4)

Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; +LR, positive likelihood ratio; -LR, negative likelihood ratio; USSS, ultrasonographic scoring system.

Correlation between LSM and histological grade of advanced fibrosis (F3-4)

The mean LSM±SD for the F0-2 and F3-4 groups were 11.8±5.8 kPa and 37.5±22.4 kPa, respectively (P<0.001). In the prediction of advanced fibrosis (F3-4), AUROC was 0.884 (95% CI 0.827-0.940) (Fig. 4). Based on the ROC curve, different cut-off values for LSM were determined. LSM ≥15.4 had Se, Sp, PPV, NPV, +LR, -LR, and accuracy of 81.82%, 79.17%, 95.58%, 44.19%, 3.93, 0.23, and 0.82, respectively, for the prediction of F3-4.

Diagnostic performance of USSS and LSM

Table 4, 5 and Figure 3,4 show the diagnostic performance and corresponding ROC curves of USSS and LSM for predicting overt fibrosis (F4) and advanced fibrosis (≥F3). Although LSM was a significant predictor of F4 fibrosis stage, USSS was superior to LSM (AUROC=0.849 vs. 0.729) (Table 4), and in the prediction of advanced fibrosis (≥F3), USSS was similar to LSM (AUROC=0.885 vs. 0.884) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

LB has been regarded as the gold standard for estimating the severity of fibrosis and diagnosing cirrhosis.1 However, noninvasive methods to estimate the stage of fibrosis have been developed,26 because LB is an invasive procedure with risk of life-threatening complications.3

Recently, LSM by TE has been identified as a promising noninvasive measurement of liver elasticity, which has a significant correlation to fibrosis.8 This novel method (with an average procedure time of ~5 min) is a safe alternative to LB for the evaluation of fibrosis in CLD.4 Additionally, several studies reported that LSM appeared to surpass US in the prediction of cirrhosis.27 However, LSM has some limitations, including the confounding effects of inflammatory activity and, to a lesser extent, steatosis on liver stiffness.28 In the case of patients with narrow intercostal spaces, ascites, or elevated liver enzymes, inspection of liver elasticity is less accurate or unworkable.4,29-32 In addition, LSM findings should be carefully interpreted, because food intake and the respiratory cycle affect liver stiffness values.33,34

US is an effective form of imaging that has been used by physicians for more than half a century.35 Because of its low cost, ease of performance, and high patient compliance,36 it has become the most common and valuable diagnostic modality for detecting not only parenchymal disease but also liver hemodynamics by Doppler imaging.37 Hence, previous studies have evaluated several methods for the diagnosis of cirrhosis using various US features.

We conducted this study to clarify whether our USSS might obtain sufficiently accurate results in comparison to the histological findings for fibrosis and those obtained by LSM. Both USSS and LSM were positively correlated with histological fibrosis (P<0.01). USSS demonstrated a larger AUROC value compared to LSM (0.849 vs. 0.729) for the prediction of overt cirrhosis (F4) (Fig. 3). Thus, USSS may be slightly superior to LSM, although both USSS and LSM were able to assess cirrhosis and may serve as an important diagnostic tool in patients with CLD. Furthermore, a USSS cut-off value of 6 permitted the diagnosis of overt cirrhosis with sensitivity of 89.2% and specificity of 69.4% (Table 4).

This study has some limitations. First, the overall AUROC of LSM for the detection of cirrhosis (F4) was lower than that reported in previous studies, which may result from the more heterogeneous population of our study, composed of alcoholic liver disease, viral hepatitis, and cryptogenic hepatitis. Second, Liver stiffness is known to depend on the architecture of fibrosis, which is affected by its etiology. Further longitudinal studies should compare USSS with LSM among a homogeneous group with the same disease etiology.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that our USSS is able to be a diagnostic tool to evaluate the degree of hepatic histological fibrosis as an alternative to LSM.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI10C2020).

Abbreviations

- CLD

chronic liver disease

- HCV

chronic hepatitis C virus

- IRB

institutional Review Board

- LB

liver biopsy

- LSM

liver stiffness measurement

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- TE

transient elastography

- US

ultrasonography

- USSS

ultrasonographic scoring system

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:495–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jun DW, Cho YK, Sohn JH, Lee CH, Kim SH, Eun JR. A study of the awareness of chronic liver diseases among Korean adults. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17:99–105. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2011.17.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Tsao G, Boyer JL. Outpatient liver biopsy: how safe is it? Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:150–153. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, et al. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, et al. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:343–350. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talwalkar JA, Kurtz DM, Schoenleber SJ, West CP, Montori VM. Ultrasound-based transient elastography for the detection of hepatic fibrosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1214–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KM, Choi WB, Park SH, Yu E, Lee SG, Lim YS, et al. Diagnosis of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis by transient elastography in asymptomatic healthy individuals: a prospective study of living related potential liver donors. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:382–388. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castera L, Forns X, Alberti A. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol. 2008;48:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziol M, Handra-Luca A, Kettaneh A, Christidis C, Mal F, Kazemi F, et al. Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis by measurement of stiffness in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:48–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sporea I, Sirli R, Deleanu A, Popescu A, Cornianu M. Liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography in clinical practice. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2008;17:395–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SU, Kim do Y, Park JY, Lee JH, Ahn SH, Kim JK, et al. How can we enhance the performance of liver stiffness measurement using FibroScan in diagnosing liver cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:66–71. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181a95c7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SU, Ahn SH, Park JY, Kang W, Kim do Y, Park YN, et al. Liver stiffness measurement in combination with noninvasive markers for the improved diagnosis of B-viral liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:267–271. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31816f212e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendoza J, Gómez-Domínguez E, Moreno-Otero R. Transient elastography (Fibroscan), a new non-invasive method to evaluate hepatic fibrosis. Med Clin (Barc) 2006;126:220–222. doi: 10.1157/13084871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baik SK, Kim JW, Kim HS, Kwon SO, Kim YJ, Park JW, et al. Recent variceal bleeding: Doppler US hepatic vein waveform in assessment of severity of portal hypertension and vasoactive drug response. Radiology. 2006;240:574–580. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402051142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seitz JF, Boustière C, Maurin P, Aimino R, Durbec JP, Botta D, et al. Evaluation of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Retrospective studies of 100 consecutive tests. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1983;7:734–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva G, Fluxá F, Hojas R, Ruiz M, Iturriaga H. Portal venous flow (ultrasonography-Doppler) in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Rev Med Chil. 1991;119:530–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaiani S, Gramantieri L, Venturoli N, Piscaglia F, Siringo S, D'Errico A, et al. What is the criterion for differentiating chronic hepatitis from compensated cirrhosis? A prospective study comparing ultrasonography and percutaneous liver biopsy. J Hepatol. 1997;27:979–985. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tüney D, Aribal ME, Ertem D, Kotiloğlu E, Pehlivanoğlu E. Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in children based on colour Doppler ultrasonography with histopathological correlation. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:859–864. doi: 10.1007/s002470050483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colli A, Fraquelli M, Andreoletti M, Marino B, Zuccoli E, Conte D. Severe liver fibrosis or cirrhosis: accuracy of US for detection--analysis of 300 cases. Radiology. 2003;227:89–94. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272020193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung CH, Lu SN, Wang JH, Lee CM, Chen TM, Tung HD, et al. Correlation between ultrasonographic and pathologic diagnoses of hepatitis B and C virus-related cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:153–157. doi: 10.1007/s005350300025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macías Rodríguez MA, Rendón Unceta P, Navas Relinque C, Tejada Cabrera M, Infantes Hernández JM, Martín Herrera L. Ultrasonography in patients with chronic liver disease: its usefulness in the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2003;95:258–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng RQ, Wang QH, Lu MD, Xie SB, Ren J, Su ZZ, et al. Liver fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis: an ultrasonographic study. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2484–2489. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiura T, Watanabe H, Ito M, Matsuoka Y, Yano K, Daikoku M, et al. Ultrasound evaluation of the fibrosis stage in chronic liver disease by the simultaneous use of low and high frequency probes. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:189–197. doi: 10.1259/bjr/75208448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu LG, Zeng MD, Wan MB, Li CZ, Mao YM, Li JQ, et al. Grading and staging of hepatic fibrosis, and its relationship with noninvasive diagnostic parameters. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2574–2578. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Tsao G, Friedman S, Iredale J, Pinzani M. Now there are many (stages) where before there was one: In search of a pathophysiological classification of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1445–1449. doi: 10.1002/hep.23478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg WM, Voelker M, Thiel R, Becka M, Burt A, Schuppan D, et al. Serum markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1704–1713. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berzigotti A, Abraldes JG, Tandon P, Erice E, Gilabert R, García-Pagan JC, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of liver surface and transient elastography in clinically doubtful cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:846–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fung J, Lai CL, Seto WK, Yuen MF. The use of transient elastography in the management of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2011;5:868–875. doi: 10.1007/s12072-011-9288-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foucher J, Chanteloup E, Vergniol J, Castéra L, Le Bail B, Adhoute X, et al. Diagnosis of cirrhosis by transient elastography (FibroScan): a prospective study. Gut. 2006;55:403–408. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.069153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coco B, Oliveri F, Maina AM, Ciccorossi P, Sacco R, Colombatto P, et al. Transient elastography: a new surrogate marker of liver fibrosis influenced by major changes of transaminases. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:360–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sagir A, Erhardt A, Schmitt M, Häussinger D. Transient elastography is unreliable for detection of cirrhosis in patients with acute liver damage. Hepatology. 2008;47:592–595. doi: 10.1002/hep.22056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arena U, Vizzutti F, Corti G, Ambu S, Stasi C, Bresci S, et al. Acute viral hepatitis increases liver stiffness values measured by transient elastography. Hepatology. 2008;47:380–384. doi: 10.1002/hep.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mederacke I, Wursthorn K, Kirschner J, Rifai K, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H, et al. Food intake increases liver stiffness in patients with chronic or resolved hepatitis C virus infection. Liver Int. 2009;29:1500–1506. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yun MH, Seo YS, Kang HS, Lee KG, Kim JH, An H, et al. The effect of the respiratory cycle on liver stiffness values as measured by transient elastography. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:631–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:749–757. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zwiebel WJ. Sonographic diagnosis of diffuse liver disease. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1995;16:8–15. doi: 10.1016/0887-2171(95)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim MY, Baik SK, Park DH, Lim DW, Kim JW, Kim HS, et al. Damping index of Doppler hepatic vein waveform to assess the severity of portal hypertension and response to propranolol in liver cirrhosis: a prospective nonrandomized study. Liver Int. 2007;27:1103–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]