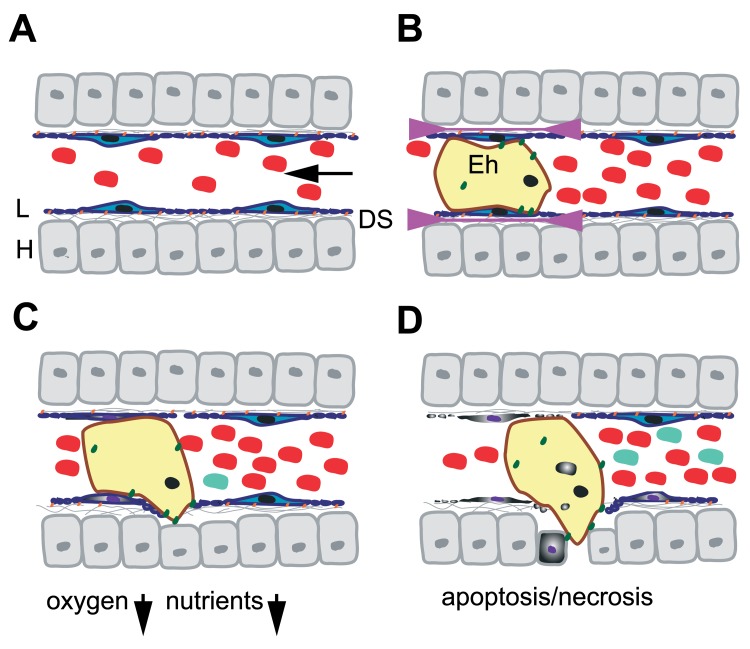

Fig. 4.

Model for the passage of E. histolytica through the liver sinusoidal barrier. A. Schematic representation of a liver sinusoid. Red blood cells circulate in the sinusoidal lumen lined by fenestrated LSEC (L; blue). LSEC adhere at FA plates (orange) to the ECM (gray lines) present in the Disse’s space (DS) and in contact which the hepatocytes (H). Stellate and Kupffer cells are not represented. The arrow indicates the direction of the blood flow. Note that the drawing is not in scale. B. During early stages of hepatic amoebiasis, E. histolytica trophozoites (yellow) obstruct hepatic sinusoid capillaries and induce LSEC retraction (indicated by arrowheads). The amoeba (10–50 µm) being bigger than the sinusoid diameter (5–7 µm), trophozoites exert mechanical forces on the endothelium. In addition, several virulence factors and adhesion molecules (green) facilitate the loss of FA complexes accelerating LSEC retraction. C. Obstruction caused by amoebae reduces the blood flow, locally creating ischemia and decreasing concentrations of oxygen and nutrients. As a consequence, the oxidative stress for the amoebae is diminished, LSEC death by apoptosis and necrosis (purple nucleus, grey cytoplasm) is induced and the inflammatory response initiated by immune cells (light blue). D. Retraction and cell death allow the amoeba to penetrate into the liver parenchyma in which it induces hepatocyte death. Phagocytosis of red blood cells, apoptotic bodies and necrotic debris provides nutrients and energy to the trophozoites. The immune response is developing