Abstract

Purpose:

Ethanol extract of Clitorea ternatea (EECT) was evaluated in diabetes-induced cognitive decline rat model for its nootropic and neuroprotective activity.

Materials and Methods:

Effect on spatial working memory, spatial reference memory and spatial working-reference memory was evaluated by Y maze, Morris water maze and Radial arm maze respectively. Neuroprotective effects of EECT was studied by assaying acetylcholinesterase, lipid peroxide, superoxide dismutase (SOD), total nitric oxide (NO), catalase (CAT) and glutathione (GSH) levels in the brain of diabetic rats.

Results:

The EECT (200 and 400 mg/kg) was found to cause significant increase in spatial working memory (P < 0.05), spatial reference memory (P < 0.001) and spatial working-reference (P < 0.001) in retention trials on Y maze, Morris water maze and Radial arm maze respectively. Whereas significant decrease in acetylcholinesterase activity (P < 0.05), lipid peroxide (P < 0.001), total NO (P < 0.001) and significant increase in SOD, CAT and GSH levels was observed in animals treated with EECT (200 and 400 mg/kg) compared to diabetic control group.

Conclusions:

The present data indicates that Clitorea ternatea tenders protection against diabetes induced cognitive decline and merits the need for further studies to elucidate its mode of action.

KEY WORDS: Clitorea ternatea, morris water maze, neuroprotective, nootropic, radial arm maze, Y maze

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most important and prevalent chronic diseases that can damage any organ in the body. Less addressed and recognized complications of DM are cognitive dysfunction, Alzheimer's disease and dementia.[1,2] Like diabetes, cognitive dysfunction represents another serious problem and is rising in prevalence worldwide, especially among the elderly. Cognitive impairment due to diabetes mainly occurs at two main periods; during the first 5-7 years of life when the brain system is in development; and the period when the brain undergoes neurodegenerative changes due to aging.[3]

Oxidative damage to various brain regions constitutes the long term complications, morphological abnormalities and memory impairments.[4] Oxidative stress becomes evident by increased lipid peroxide, nitric oxide (NO) levels and decreased glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT)levels.[5] Neurotransmitter functions which are altered in DM include decreased acetylcholine production, decreased serotonin turnover, decreased dopamine activity and increased norepinephrine.[3] Substantial experimental evidence exists for a relation between the decline in cholinergic functions and dementia.[6]

‘Diabetes-associated cognitive decline’ is a new term proposed to facilitate research in Diabetic encephalopathy. Hyperglycemia, oxidative stress and cholinergic decline play a central role in cognitive impairment in diabetic encephalopathy.[6,7] Anti-diabetic and psychotropic drugs are associated with several adverse effects and this has spurred the need for exploring drugs without side effects especially, from traditional system of medicine like Ayurveda, Siddha and Unani. In Ayurveda the roots, seeds and leaves of Clitorea ternatea Linn. (Fabaceae) have long been widely used as a brain tonic and is believed to endorse memory and intelligence.[8] It is reported to have antidepressant, anticonvulsant,[9] anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic,[10] local anesthetic,[11] purgative[12] and anti-diabetic[13] activity. It is also used for treatment of snakebite and scorpion sting in India.[14] Since the plant is reported to be used by the traditional system of medicine as anti-diabetic, brain tonic and believed to promote memory and intelligence; authors have premeditated this study to explore the nootropic and neuroprotective potential of Ethanol extract of Clitorea ternatea (EECT)leaves in experimental model for DM induced cognitive decline.

Materials and Methods

Collection and identification of plant material

The leaves of Clitorea ternatea were collected in the month of November 2009 from the local areas of Pune; Maharashtra. The plant material was authenticated at Botanical Survey of India; Pune and voucher specimen: BB680518 was deposited.

Preparation of extract

The leaves were dried under shade and later pulverized in a mechanical grinder. The 100 g of powder was then extracted with ethanol (95%) for a week. The mixture was then filtered and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to yield semisolid (3.70%w/w) extract. This semisolid extract was preserved in the refrigerator in airtight container till further use.

Selection and maintenance of animals

Adult Sprague Dawley rats of either sex, weighing between 150-250 g were used for the study. The animals were housed in standard polypropylene cages at room temperature and provided with standard diet and water ad libitum. The experimental protocol has been approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (SCOP/IAEC/Approval/2009-10/10). The animals were shifted to the laboratory one hour prior to the experiment.

Drugs and chemicals

Metformin was obtained as gift sample from Cipla Pharmaceuticals Ltd, India, Piracetam (Nootropil, 80 mg tab), Streptozotocin (Sigma Aldrich, USA), Diagnostic Kits (Biolab, India), MDA, SOD, CAT (Sigma Aldrich, USA), GSH (LobaChem, India) were purchased from local market. Other chemicals of analytical grade were obtained from Qualigens, India.

Administration of dosage

The EECT suspension was prepared in 2% acacia using mortar and pestle and administered orally to rats at various doses.[15] Metformin, piracetam were used as standard drugs and administered orally at a dose of 200 mg/kg in distilled water.

Induction of DM

Streptozotocin (STZ) dissolved in cold citrate buffer (pH 4.45, 0.1 M) was administered intraperitoneally (55 mg/kg) to induce diabetes. After 48 hours of STZ injection, blood samples were collected by puncturing retro-orbital plexus of rats under light ether anesthesia using fine glass capillary in epindorff tubes and serum glucose level was estimated by glucose oxidase and peroxidaseoxidase enzymatic method. Animals with serum glucose more than 250 mg/dl considered as diabetic and used for the further study.[16,17]

Study Design

Phytochemical study

EECT was evaporated to residue and dilute HCl was added -to it. After shaking, extract was filtered and with filtrate tests were performed for the detection of various constituents using conventional protocol like Mayer's, Wagner's, Hagner's, and Dragendorff's tests for alkaloids; Baljet's, Borntrager's, Legal's tests for glycosides; foam and hemolytic tests for saponins; Salkowski's and Lieberman – Buchard's tests for steroids/triterpenoids; Gelatin and Ferric chloride tests for tannins; Ferric chloride, Shinoda, Alkaline reagent and Lead acetate solution test for flavonoids; Molisch's and Benedict's tests for carbohydrates; Millon's and Ninhydrin tests for proteins and amino acids respectively.[18]

Acute toxicity study

Acute toxicity study was carried out according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines No. 423. Three animals were used for each step. The starting dose was selected from the four fixed dose levels, i.e., 5, 50, 300, and 2000 mg/kg body weight p.o. As per the OECD recommendations, 300 mg/kg body weight was used as starting dose.

Nootropic study

The EECT was tested for nootropic studies using rats as per the method suggested by Lucian et al., Morris et al., Tuzcu and Baydas, Carrillo et al.[19,20,21,22] The selected animals were divided into six groups with six animals in each. The control groups (normal and diabetic) received 2% gum acacia 5 ml/kg/day orally. The standard groups received metformin and piracetam in the dose of 200 mg/kg/day, the test groups received the EECT 200 and 400 mg/kg/day orally.

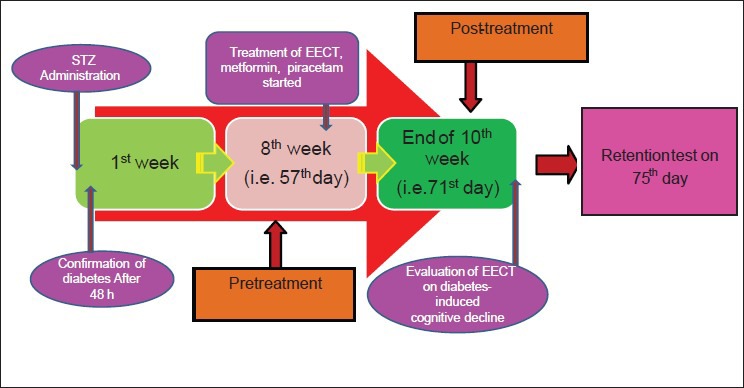

Y maze test

Short-term memory was assessed by spontaneous alternation behavior in the Y-maze task. The Y-maze used in the present study consisted of three arms (35 cm long, 25 cm high and 10 cm wide) and an equilateral triangular central area. Animal was placed at the end of one arm and allowed to move freely through the maze. Time limit in Y-maze test was fixed to 8 minutes hence, every session ended after 8 minutes. An arm entry was counted when the hind paws of the rat were completely within the arm. Spontaneous alternation behavior was defined as entry into all three arms on consecutive choices. The number of maximum spontaneous alternation behaviors was then the total number of arms entered minus 2. Percent spontaneous alternation was calculated as (actual alternations/maximum alternations) × 100.[19] The animals were trained for five days and % spontaneous alteration measured on 71st and 75th day [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Experimental study design

Morris water maze test

On 71st day animals were tested in a spatial version of Morris water maze. The apparatus consisted of a circular water tank (180 cm in diameter and 60 cm high). A platform (12.5 cm in diameter and 38 cm high) invisible to the animals, was set inside the tank and filled with water maintained at 28 ± 2°C at a height of 40 cm. The tank was located in a large room where there were several brightly colored cues external to the maze; these were visible from the pool and could be used by the animals for spatial orientation. The position of the cues was kept unchanged throughout the study. The water maze task was carried out for 5 consecutive days of the post-treatment. The animals received daily training trials for first four of these 5 consecutive days. Each trial was of 90 seconds and with a trial interval of approximately 30 seconds. For each trial, each animal was put into the water at one of four starting positions, the sequence of which being selected randomly. During test trials, animals were placed into the tank at the same starting point, with their heads facing the wall. The animal had to swim until it climbs- the platform submerged underneath the water. After climbing -the platform, the animal was allowed to remain there for 20 seconds before the commencement of the next trial. The escape platform was kept in the same position relative to the distal cues. If the animal failed to reach the escape platform within the maximum allowed time of 90 seconds, it was gently placed on the platform and allowed to remain there for the same time. The time to reach the platform (latency in seconds) was measured.

A probe trial was performed wherein the extent of memory consolidation was assessed. In the probe trial, the animal was placed into the pool as in the training trial, except that the hidden platform was removed from the pool. The transfer latency (TL) to reach platform was measured on 75th day to study spatial reference memory.[20,21]

Radial arm maze test

The radial maze is the prototype of a “multiple-solution problem” task. Effect of EECT on spatial working-reference was studied by using radial arm maze. It consisted of 8 arms, numbered from 1 to 8 (48 × 12 cm) extending radially from a central area (32 cm in diameter). The apparatus was placed 40 cm above the floor, and surrounded by various extra maze cues placed at the same position during the study. At the end of each arm there was a food cup that had a single 50 mg food pellet. Prior to the performance of the maze task, the animals were kept on restricted diet. Before the actual training begun, three or four rats were simultaneously placed in the radial maze and allowed to explore for 5 minutes to take food freely. The food was initially made available throughout the maze, but then -gradually restricted to the food cup. The animals were shaped for 4 days to run to the end of the arms and consume the bait. The rats were given 5 consecutive training trials to run to the end of the arms and consume the bait. The training trial continued until all the 5 baits were consumed or until all 5 minutes elapsed. Criterion for performance was defined as consumption of all 5 baits or 5 min time elapse.

After adaptation all rats were trained with 1 trial per day. Briefly, each animal was placed individually in the center of the maze and subjected to spatial working-reference tasks, in which same 5 arms (no. 1, 2, 4, 5, and 7), were baited for each daily training trial. The other 3 arms (no. 3, 6, 8) were never baited. The training trial continued until all 5 baits were consumed or until 5 minutes elapsed. An arm entry was counted when all four limbs of the rat were within an arm. On 71st and 75th day; mean spatial working-reference was measured. Spatial working memory was defined by the ratio; number of food rewarded visits/number of all visits to the baited arms. This measure represents the percentage of all visits to the baited arms that had been reinforced with food. Spatial reference memory was defined by the ratio; number of all visits to the baited arms/total number of visits to all arms. This measure expresses the number of visits to the baited arms as a percentage of the total number of visits to all arms. The time taken to consume all 5 baits was also recorded.[19]

Neurochemical study

Post-treatment animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and brain was isolated and weighed. Whole brain was rinsed with ice cold saline (0.9% sodium chloride) and homogenized by making 20 mg of the tissue per ml in chilled phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The homogenates were centrifuged at 800 g for 5 minutes at 4°C to separate the nuclear debris. The supernatant thus obtained was centrifuged at 10500 g for 20 minutes at 4°C to get the supernatant. Such obtained supernatant was then used for neurochemical study.[23,24,25,26,27,28] The protein concentration was estimated by Lowry et al., (1951) method using bovine serum albumin as the standard.[29]

Acetylcholinesterase assay

For estimation of acetylcholinesterase activity, Ellman's method named after George Ellman was used.[21] A total of 0.4 ml supernatant was added to a cuvette containing 2.6 ml phosphate buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH 8) and 100 μL of 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid). The contents of the cuvette were mixed thoroughly by bubbling air and absorbance was measured at 412 nm by a spectrophotometer. When absorbance reaches a stable value, it was recorded as the basal reading. The substrate of 20 μLof acetylthiocholineiodide was added and the changes in absorbance were recorded for a period of 10 minutes at intervals of 2 minutes. Change in the absorbance per minute was thus determined.

The mean change in absorbance was considered for calculation using following formula and acetylcholinesterase activity was measured as μM/l/min/gm of tissue.[23]

Where, R = Rate, in moles substrate hydrolyzed per minutes per gm of tissue

∆A = Change in absorbance per minutes.

Co = Original concentration of tissue (20 mg/ml).

Lipid peroxide levels

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) levels are measured as an index of malondialdehyde (MDA) production which is an end product of lipid peroxidation. MDA reacts with thiobarbituric acid to form a red colored complex. The measurement of MDA levels by thiobarbituric acid reactivity is the most widely used method for assessing lipid peroxidation. For this 0.5 ml of Tris hydrochloric acid was added in 0.5 ml of supernatant and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. After incubation 1 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes, and then 1ml of 0.67% thiobarbituric acid was added to 1 ml of supernatant. The tubes were kept in boiling water for 10 minutes. After cooling 1 ml double distilled water was added and absorbance was measured at 532 nm. The MDA concentrations of the samples were derived from the standard curve prepared using known amounts of MDA and expressed as nmol MDA/mg of protein.[24]

Total nitric oxide levels

To 100 μl of supernatant, 500 μl of Greiss reagent (1:1 solution of 1% sulphanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid and 0.1% naphthalene diamine dihydrochloride) was added and absorbance was measured at 546 nm. Nitrite concentration was calculated using a standard curve for sodium nitrite and expressed as ng/mg of protein.[25]

Superoxide dismutase levels

To 100 μl of supernatant, 1ml of sodium carbonate (1.06 g in 100 ml water), 0.4 ml of 24 mmol/L NBT (nitroblutetrazolin) and 0.2 ml of Ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid [EDTA (37 mg in 100 ml water)] was added, and zero minute reading was taken at 560 nm. Reaction was initiated by addition of 0.4 ml of 1mM hydroxylamine hydrochloride, incubated at 25°C for 5 minutes and the reduction of NBT was measured at 560 nm. SOD level was calculated using the standard calibration curve, and expressed in μg/mg of protein.[26]

Catalase levels

Catalase activity was assayed by the method of Claiborne (1985). To 100 μl of supernatant, 1.9 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 7) was added and absorbance was read at 240 nm. The reading was taken again 1 minute after adding 1 ml of 0.019 mol/Lhydrogen peroxide solution to the reaction mixture. One international unit of catalase utilized is that amount that catalyzes the decomposition of 0.019 mol/Lhydrogen peroxide/min/mg of protein at 37°C. Catalase activity was calculated using the standard calibration curve, and expressed as μg/mg of protein.[27]

Glutathione levels

1 ml of 10% supernatant was precipitated with 1ml of 4% sulphosalicylic acid. The samples were kept at 4°C for at least 1 hour and then subjected to centrifugation at 1200 g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The assay mixture contained 0.1 ml supernatant, 2.7 ml phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and 0.2 ml DTNB (5, 5, dithiobis 2-nitro benzoic acid) Ellman's reagent, in a total volume of 3 ml. The yellow color developed was read immediately at 412 nm and expressed as μg/mg of protein. The GSH concentrations of the samples were derived from the standard curve prepared using known amounts of GSH and expressed as ng/mg protein.[28]

Statistical analysis

The mean ± SEM values were calculated for each group. Student t- test was used for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

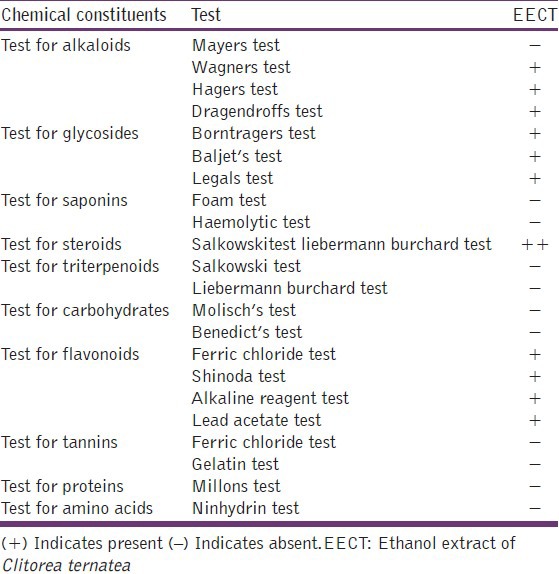

Phytochemical analysis

Total extract yield was (3.70% w/w). Phytochemical screening of the extract determined presence of alkaloids, glycosides, steroids and flavonoids as major constituents, while tannins, triterpenoids, saponins, carbohydrates, proteins and amino acids were found absent [Table 1].

Table 1.

Details of qualitative phytochemical tests

Acute toxicity study

The results of acute toxicity study showed no clinical signs of toxicity and mortality in the EECT treated animals even after administration of 2000 mg/kg dose. Hence, as per OECD guidelines lethal dose was assigned to be more than 2000 mg/kg. 1/10th and 1/5th of this lethal dose (i.e. 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg) were taken as effective doses for the study.

Nootropic study

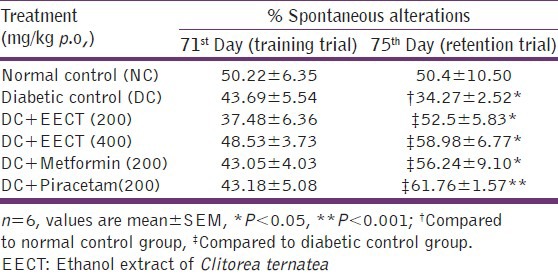

Effects of EECT on spontaneous alterations (%) in Y maze arm

spontaneous alteration of diabetic controls was significantly (P < 0.05) decreased in retention trial as compared to normal controls, EECT (200 and 400 mg/kg), metformin (200mg/kg) and piracetam (200 mg/kg) treated diabetic animals showed significant (P < 0.05), increase in % spontaneous alterations in retention trial as compared to diabetic controls [Table 2].

Table 2.

Effects of EECT on spontaneous alterations (%) in Y maze arm of diabetes-induced cognitive decline model

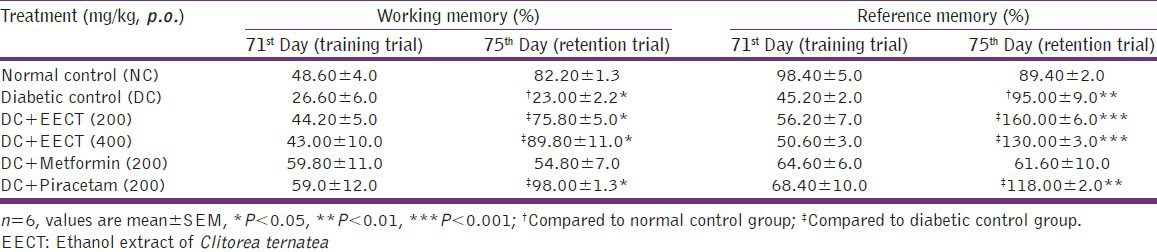

Effects of EECT on spatial working and reference memory in Radial arm maze

Spatial working-reference memory of diabetic controls was significantly (P < 0.01) decreased in retention trial as compared to normal controls. Diabetic animals, treated with EECT (200 and 400 mg/kg) showed dose dependent (P < 0.001) increase in spatial working-reference memory in retention trial as compared to diabetic controls. Whereas piracetam (200 mg/kg) treated diabetic animals showed significant increase in spatial working (P < 0.001) and reference memory (P < 0.01) in retention trial as compared to diabetic controls. Treatment with metformin (200 mg/kg) however, produced insignificant effect on spatial working-reference memory [Table 3].

Table 3.

Effects of EECT on spatial working and reference memory in radial arm maze of diabetes.induced cognitive decline model

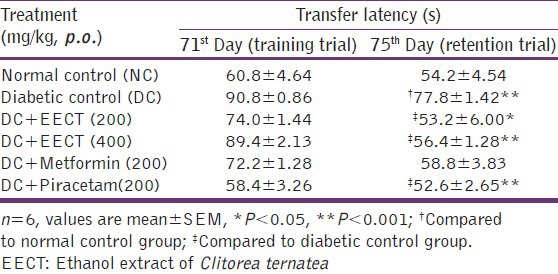

Effects of EECT on transfer latency in morris water maze

No significant difference observed in TL in animals during training. In retention trial, TL was found to be significantly (P < 0.001) increased in diabetic controls as compared to normal controls. Two weeks repeated treatment with EECT (200 and 400 mg/kg) and piracetam (200 mg/kg) significantly (P < 0.001) decreased TL in retention trial as compared to diabetic controls whereas this effect was found insignificant in metformin (200 mg/kg) treated animals [Table 4].

Table 4.

Effects of EECT on transfer latency in morris water maze of diabetes-induced cognitive decline models

Neurochemical study

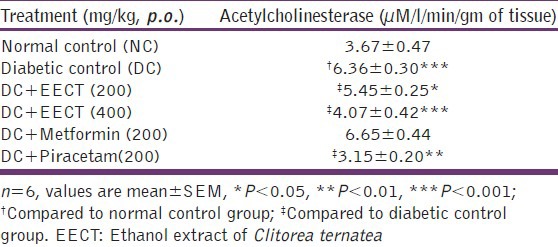

Effects of EECT on acetylcholinesterase activity

Acetylcholinesterase activity was significantly increased in diabetic controls (P < 0.001) compared to normal controls, suggestive of cholinergic dysfunction. While two weeks repeated treatment with EECT (200 and 400 mg/kg) significantly decreased acetylcholinesterase activity in diabetic animals (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001 respectively). Piracetam (200 mg/kg) treated group showed significant (P < 0.001) decrease, whereas metformin (200 mg/kg) showed insignificant effect in this regard [Table 5].

Table 5.

Effects of EECT onacetylcholinesterase activity of diabetes-induced cognitive decline models

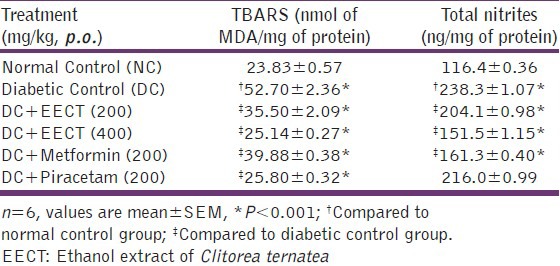

Effects of EECT on lipid peroxide and total nitric oxide levels

Significant (P < 0.001) increase was observed in TBARS and NO levels in diabetic controls compared to normal controls. Two weeks repeated treatment with EECT (200 and 400 mg/kg) and metformin (200 mg/kg) showed significant (P < 0.001) reduction in TBARS and NO in diabetic animals whereas, piracetam (200 mg/kg) though showed significant (P < 0.001) reduction in TBARS levels; had insignificant effect on brain NO level [Table 6].

Table 6.

Effects of EECT on lipid peroxide and total nitrites levels of diabetes-induced cognitive decline models

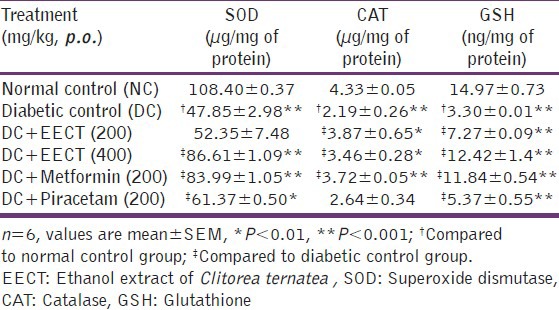

Effects of EECT on superoxide dismutase, catalase and reduced glutathione levels

The results showed significant (P < 0.001) decrease in SOD, CAT and GHS levels in diabetic controls compared to normal controls. Two weeks repeated treatment with EECT (400 mg/kg) showed significant improvement in SOD (P < 0.001), CAT (P < 0.01) and GSH (P < 0.001) levels whereas, EECT (200 mg/kg) caused significant increase in CAT (P < 0.01) and GSH (P < 0.001) levels with no significant increase in diabetic animals. Metformin (200 mg/kg) showed significant (P < 0.001) increase in SOD and CAT levels and no significant effect on GSH levels. Piracetam (200 mg/kg) showed significant increase only in SOD (P < 0.01) and GSH (P < 0.001) levels [Table 7].

Table 7.

Effects of EECT on SOD, CAT and GSH levels of diabetes-induced cognitive decline models

Discussion

The incidence of dementia appears to be doubled in elderly subjects with diabetes.[30,31] The potential mechanisms for this include direct effects of hypo or hyperglycemia and hypo or hyperinsulinemia, and also indirect effects e.g. oxidative stress, neurochemical changes causing cerebrovascular alterations.[32,33]

Large numbers of plants are used in treatment of cognitive decline. Earlier studies have reported that administration of Clitorea ternatea leaves extract significantly decrease the level of blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin, increase serum insulin to normal level in alloxan-induced diabetic animals.[13] The methanolic extract of Clitorea ternatea has been studied for its effect on cognitive behavior, anxiety, depression, stress and convulsions induced by pentylenetetrazol and maximum electroshock. To explain these effects, the effect of Clitorea ternatea was also studied on behavior mediated by dopamine, noradrenaline, serotonin and acetylcholine.[9] Hence, it was thought worth to investigate the effects of Clitorea ternatea on diabetes induced cognitive decline in experimental animals along with its role in oxidative stress and acetylcholinesterase activity. The cognitive decline study was focused on spatial working and spatial reference memory based mazes.

The preliminary phytochemical screening showed presence of alkaloids, glycosides, flavonoids, steroids in EECT leaves. Various phytochemicals like flavonoids, anthocyanin glycosides, pentacyclictriterpenoids, and phytosterols have been reported from this plant.[8] The literature survey revealed cognitive impairment in STZ-induced diabetic animals in eight weeks.[34] Our results are in agreement with this in diabetic animals. Treatment of EECT was scheduled for two weeks after cognitive decline. Results of present study showed significant improvement in spatial working memory, spatial reference memory and spatial working-reference memory suggestive of nootropic activity of EECT in diabetes induced cognitive decline models.

The increased oxidative stress in diabetes produces oxidative damage in many regions of brain including the hippocampus[4] this oxidative damage in the brain is increased by experimentally induced hyperglycemia.[35] Oxidative damage to various brain regions constitutes the long term complications, morphological abnormalities and memory impairments. In the present study, TBARS and NO levels were significantly increased (P < 0.001) whereas GSH, SOD and CAT levels were markedly reduced in the brain of diabetic controls. Treatment with EECT significantly reduced the levels of TBARS, whereas GSH, SOD and CAT levels were increased. Therefore, EECT might have protective effect against diabetes induced cognitive decline due to reduced oxidative stress. The antioxidant properties of EECT might help to ameliorate the cognitive dysfunction in diabetic animals.

Release of acetylcholine in the hippocampus is positively correlated with training on a working memory task[36] and with good performance on a hippocampus-dependent, spontaneous alteration task.[37] In diabetes the acetylcholinesterase levels are found to be high; this enzyme hydrolyses acetylcholine present in the brain and results in cognitive decline.[38] We observed a significant rise in acetylcholinesterase activity in the brain of diabetic rats. Two week treatment with EECT attenuated increase in acetylcholinesterase activity in the brain of diabetic animals. Hence, EECT treatment ameliorated cognitive decline, cholinergic dysfunction, reduced oxidative stress, and NO in the diabetic animals may find clinical application in treating neuronal deficit in the diabetic patients.

Conclusion

To conclude, the results of present study showed improvement in spatial working as well as reference memory in maze based studies. Neurochemical study revealed decrease in acetylcholinesterase, MDA and NO levels with increased SOD, GSH and CAT levels in the brain. Thus, the present data indicates that Clitorea ternatea offers protection against diabetes induced cognitive decline and justifies the need for further studies to elucidate its mode of action.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to BSI Pune for identification of plant material. The authors thank to Dr. Jain, Principal Sinhgad College of Pharmacy Vadgaon for providing facilities to carry out of the experiments of this work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Blennow K, Leon de MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao Y, Ye W, Boye KS, Holcombe JH, Hall JA, Swindle R. Prevalence of other diabetes-associated complications and co morbidities and its impact on health care charges among patients with diabetic neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roriz-Filho JS, Ticiana MS, Idiane R, Ana LC, Antonio CS, Márcia LF, et al. (Pre) diabetes, brain aging, and cognition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:432–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baynes JW. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40:405–12. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, Nelson J, Davis DG, Ross GW, et al. Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied. Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Artola A. Diabetes, stress and ageing related changes in synaptic plasticity in hippocampus and neocortex the same metaplastic process? Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585:153–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–17. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukherjee PK, Kumar V, Mal M, Houghton PJ. Acetyl cholinesterase inhibitors from plants. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain NN, Ohal CC, Shroff SK, Bhutada RH, Somani RS, Kasture VS, et al. Clitorea ternatea and the CNS. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:529–36. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parimaladevi B, Boominathan R, Mandal SC. Evaluation of antipyretic potential of Clitorea ternatea L. Extract in rats. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:323–6. doi: 10.1078/0944711041495191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulkarni C, Pattanshetty JR, Amruthraj G. Effect of alcoholic extract of Clitorea ternatea Linn on central nervous system in rodents. Indian J ExpBiol. 1988;26:957–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadkarni KM. 3rd ed. Bombay: Popular Publication; 1976. Indian Materia Medica. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daisy P, Rajathi M. Hypoglycemic effects of Clitorea ternatea Linn. (Fabaceae) in alloxan-induced diabetes in rats. Trop J Pharm Res. 2009;8:393–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Allahabad: Lalit Mohan Basu; 1935. Indian Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chauhan N, Rajvaidhya S, Dubey BK. Antiasthmatic effect of roots of Clitorea ternatea Linn. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2012;3:1076–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trinder P. Determination of glucose in blood using glucose oxidase with an alternative oxygen acceptor. Ann Clin Biochem. 1969;6:24–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghavan G, Madhavan V, Rao C, Kumar V, Rawat AK, Pushpangadan P. Action of Asparagus racemosus against streptozotocin-induced oxidative stress. J Nat Prod Sci. 2004;10:177–81. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khandelwal KR. 19th ed. Pune: Niraliprakashan; 2008. Practical pharmacognosy. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucian H, Monica C, Toshitaka N. Brain serotonin depletion impairs short-term memory, but not Long-term memory in rats. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:652–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JB, Janick J, editors. Alexandria, VA, USA: ASHS Press, Inc; 1999. Legume genetic resources with novel value added industrial and pharmaceutical use. Perspectives on New crops and New Uses; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuzcu M, Baydas G. Effect of melatonin and vitamin E on diabetes-induced learning and memory impairment in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;537:106–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrillo MP, Giordano M, Santamaria A. Spatial memory: Theoretical basis and comparative review on experimental methods in rodents. Behav Brain Res. 2009;203:151–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellman GL, Courtney DK, Andres V, Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wills ED. Mechanism of lipid peroxide formation in animals. Biochem J. 1965;99:667–76. doi: 10.1042/bj0990667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N] nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kono Y. Generation of superoxide radical during autoxidation of hydroxylamine and an assay for superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;186:189–95. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Claiborne A, Greenwald RA, editors. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Inc; 1985. Catalase activity. Handbook of methods for oxygen radical research; pp. 283–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Zampaglione N, Gillette JR. Bromobenzene induced liver necrosis: Protective role of glutathione and evidence for 3,4-bromobenzenoxide as the hepatotoxic metabolite. Pharmacology. 1974;11:151–69. doi: 10.1159/000136485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the folinphenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ott A, Stolk RP, Van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofinan A, Breteler MM. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam study. Neurology. 1999;53:1937–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peila R, Rodriguez BL, Launer LJ. Type 2 diabetes, APOE gene, and the risk for dementia and related pathologies: The Honolulu-Asia aging study. Diabetes. 2002;51:1256–62. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brands AM, Biessels GJ, Haan de EH, Kappelle LJ, Kessels RP. The effects of type 1 diabetes on cognitive performance: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:726–35. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lobnig BM, Krömeke O, Optenhostert-Porst C, Wolf OT. Hippocampal volume and cognitive performance in long-standing type 1 diabetic patients without macrovascular complications. Diabet Med. 2005;23:32–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patil CS, Singh VP, Kulkarni SK. Modulatory effect of sildenafil in diabetes and electroconvulsive shock-induced cognitive dysfunction in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2006;58:373–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aragno MR, Mastrocola E, Brignardello M, Catalano M, Robino G, Manti R, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone modulates nuclear factor kappa activation in hippocampus of diabetic rats. J Endocrinol. 2002;143:3250–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fadda F, Mellis F, Stancampiano R. Increased hippocampal acetylcholine release during a working memory task. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;307:R1–2. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ragozzino ME, Gold PE. Glucose injections into the medial septum reverse the effects of intraseptal morphine infusions on hippocampal acetylcholine output and memory. Neuroscience. 1995;68:981–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00204-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dougherty KD, Turchin PI, Walsh TJ. Septocingulate and septohippocampal cholinergic pathways: Involvement in working/episodic memory. Brain Res. 1998;810:59–71. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]