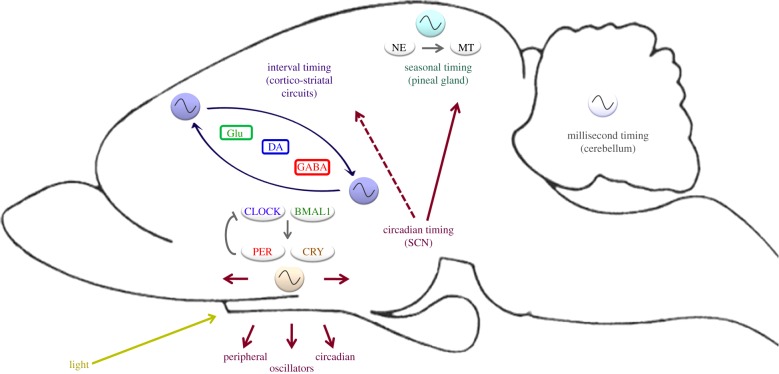

Figure 4.

A network of oscillators regulates timing behaviour. The model represents mechanisms responsible for seasonal, circadian, interval and millisecond timing. In seasonal timing, the pineal gland allows mammals to respond to the annual changes in photoperiod by adaptive alterations of their physiological state. Melatonin, the major hormone produced by the pineal gland, displays daily and seasonal patterns of secretion which synchronize numerous physiological processes in photoperiodic species. In the range of approximately 24 h, circadian timing operates through a self-sustaining oscillator whose location in mammals is the SCN in the hypothalamus. The SCN controls several endocrine, metabolic and behavioural functions through peripheral oscillators. In the seconds-to-minutes range, interval timing depends upon cortico-striatal circuits. In the higher frequency range, millisecond timing has been proposed to depend upon a sensory-motor network that includes the cerebellum. These different oscillators can interact between themselves. Thus, release of melatonin by the pineal gland is mainly driven by the circadian clock, which controls the release of norepinephrine from the dense pineal sympathetic afferents. The circadian system could also modulate interval timing, perhaps through regulation of DA rhythms in the brain. BMAL1, brain and muscle ARNT-like 1; CLOCK, circadian locomotor output cycles kaput; CRY, cryptochrome; DA, dopamine; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; Glu, glutamate; MT, melatonin; NE, norepinephrine; PER, period. (Online version in colour.)