Abstract

Introduction

There is sparse literature on how best to correct Scheuermann’s kyphosis (SK). The efficacy of a combined strategy with anterior release and posterior fusion (AR/PSF) with regard to correction rate and outcome is yet to be determined.

Materials and methods

A review of a consecutive series of SK patients treated with AR/PSF using pedicle screw–rod systems was performed. Assessment of demographics, complications, surgical parameters and radiographs including flexibility and correction measures, proximal junctional kyphosis angle (JKA + 1) and spino-pelvic parameters was performed, focusing on the impact of curve flexibility on correction and clinical outcomes.

Results

111 patients were eligible with a mean age of 23 years, follow-up of 24 months and an average of eight levels fused. Cobb angle at fusion level was 68° preoperatively and 37° postoperatively. Flexibility on traction films was 34 % and correction rate 47 %. Postoperative and follow-up Cobb angles were highly correlated with preoperative bending films (r = 0.7, p < 0.05). Screw density rate was 87 %, with increased correction with higher screw density (p < 0.001, r = 0.4). Patients with an increased junctional kyphosis angle (JKA + 1) were at higher risk of revision surgery (p = 0.049). 22 patients sustained complication, and 21 patients had revision surgery. 42 patients with ≥24 months follow-up were assessed for clinical outcomes (follow-up rate for clinical measures was 38 %). This subgroup showed no significant differences regarding baseline parameters as compared to the whole group. Median approach-related morbidity (ArM) was 8.0 %, SRS-sum score was 4.0, and ODI was 4 %. There was a significant negative correlation between the SRS-24 self-image scores and the number of segments fused (r = −0.5, p < 0.05). Patients with additional surgery had decreased clinical outcomes (SRS-24 scores, p = 0.004, ArM, p = 0.0008, and ODI, p = 0.0004).

Conclusion

The study highlighted that AR/PSF is an efficient strategy providing reliable results in a large single-center series. Results confirmed that flexibility was the decisive measure when comparing surgical outcomes with different treatment strategies. Findings indicated that changes at the proximal junctional level were impacted by individual spino-pelvic morphology and determined by the individually predetermined thoracolumbar curvature and sagittal balance. Results stressed that in SK correction, reconstruction of a physiologic alignment is decisive to achieving good clinical outcomes and avoiding complications.

Keywords: Scheuermann’s kyphosis, Kyphotic deformity, Spinal release, Outcome, Surgical correction

Introduction

Comprehensive series on outcomes of surgical treatment for Scheuermann’s kyphosis (SK) are few [7–11]. Accordingly, there remains significant discussion regarding the ideal strategy to correct SK, and the ideal kyphosis that should be targeted in each individual is yet to be determined. While some recommend anterior release and posterior instrumented spinal fusion (AR/PSF) for curves, e.g., not bending down ≤50° on hyperextension films [3, 12–16], others report that most curves can be treated with PSF, irrespective of size [8, 19]. Recommendations are based on relatively small sample sizes and heterogeneous groups. The efficacy of each technique is yet to be elucidated. A recent complications review by the SRS reported no significant difference between 338 posterior-only and 272 AR/PSF (15 % vs. 17 %) [11]. The authors stressed, however, that the impact of a combined approach with regard to correction rates, loss of correction, perioperative and long-term outcomes as well as the incidence of junctional problems needs to be determined in larger samples. Notably, the flexibility of kyphosis and number of levels fused are frequently neglected [19]. Despite curve flexibility being an established predictor for curve correction in scoliosis surgery [21], it is frequently not addressed in the treatment of SK, although it might be the most significant factor in the decision-making process for each individual curve.

Only a few studies describe the outcomes of surgical correction of SK using pedicle screw-only constructs [23]. By analyzing the outcomes of a large single-center series using AR/PSF and pedicle screw-only constructs for the treatment of SK, the authors sought to provide a valuable sample for comparison and refinement of the indications for posterior-only versus combined strategy. Emphasizing the analysis of the efficacy of a combined treatment, the current study focused on the interdependence of correction and preoperative curve flexibility, complications, approach-related morbidity and clinical outcomes

Materials and methods

This was a case series review of patients with SK operated on using AR/PSF in 2000–2008. Minimum follow-up for inclusion was 6 months (to assess all perioperative complications). Medical charts were analyzed for demographics, surgical details, perioperative complications, incidence and indications for revision surgery and analysis of clinical outcome. Patients with a 24-month follow-up were invited for clinical survey. Surgical files and radiographs were scanned for implants used, number of levels fused, end levels and screw density. Screw density (%) was calculated from the number of pedicle screws inserted and the maximum possible (Fig. 1). Complications were stratified according to Glassman [25]. Revision surgeries were stratified into: minor, e.g., superficial wound irrigation and debridement; major, including revisions for mechanical concerns.

Fig. 1.

Examples of instrumentation pattern: segmental all-pedicle screw (a) versus selective/skip (b) instrumentation resulting in varying screw density rates

Radiographs

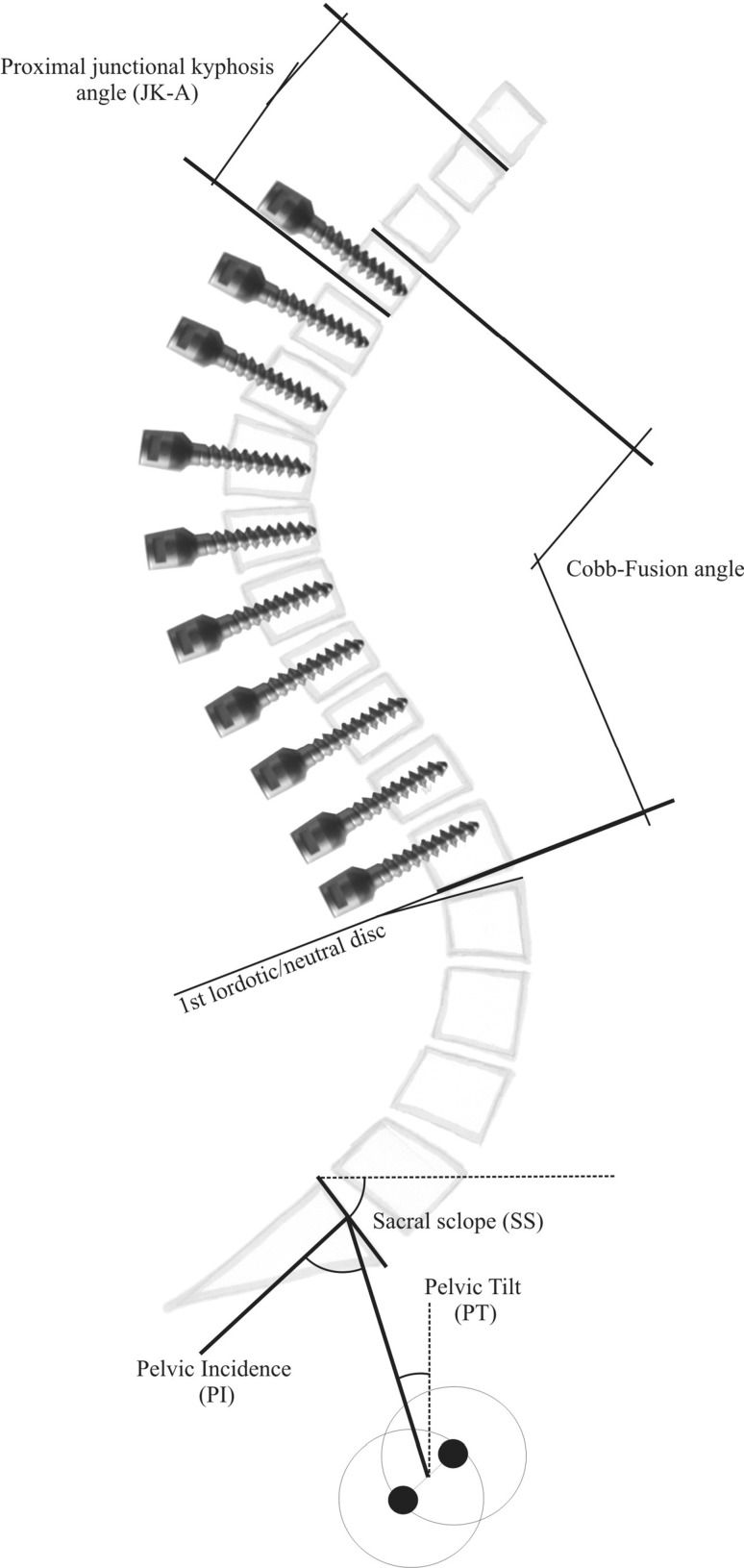

Patients had preoperative, postoperative and follow-up full-length standing biplanar radiographs. Preoperatively, patients had a hyperextension radiograph with the patient lying extended over a bolster beneath the apex of the kyphosis (HE-radiograph, Fig. 2a) and/or another radiograph with the patient applying traction in a Cotrel-traction apparatus (traction-radiographs, Fig. 2b). Measurements were performed using the Cobb angle method. Proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK) was assessed in terms of the junctional kyphosis angle and with all other radiographic parameters explained in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative analysis of flexibility was performed on (a) HE-radiographs or on (b) traction-radiographs with the patient applying distraction in a Cotrel-traction apparatus. Calculation of flexibility was by comparing neutral full-standing radiographs to the bending radiographs

Fig. 3.

Technique for measuring main radiographic parameters: sagittal radiographs were assessed for thoracic kyphosis T4–T12 (TK), lumbar lordosis L1–S1 (LL), Cobb angle of levels in the fusion mass including maximum kyphosis measured from the most proximal to the most distal vertebra of that curve (Fusion-Cobb), thoracolumbar junctional angle T10–L2 (TLA), sacral slope (SS), pelvic tilt (PT), deviation of the C7-sagittal plumbline (C7-SPL) off the S1-posterior endplate (in cm) and proximal junctional kyphosis angle (JKA + 1). JKA + 1 is the angle obtained by the lower endplate tangent of the upper instrumented vertebra and the upper endplate tangent of the vertebra two levels cephalad to the upper instrumented vertebra [3]. On lateral radiographs, the level of the first-lordotic disc was detected. For follow-up radiographs, the difference between a predicted high lumbar lordosis L1–S1, as by the equation LL = PI + 9° [5], and the real lumbar lordosis was calculated

Preoperative flexibility of kyphosis was calculated on HE-radiographs and traction-radiographs using the following equation: Bending flexibility (%) = [(preop bending − Cobb)/preop Cobb] × 100. Correction rate and loss of correction were calculated accordingly. On the AP radiograph coronal balance was measured by dropping a C7-plumbline and measuring its offset from the center sacral vertical line (C7-SVL, in cm). Scoliosis exceeding 20° was measured using the Cobb angle method. Changes in construct alignment, failure of instrumentation, distal junctional kyphosis (DJK) with loosening or pullout of screws and evidence of non-union were recorded. Diagnosis of non-union was made when there was radiographic evidence of it or instrumentation failure, loosening or motion during surgical exploration.

Clinical outcome

Patients were invited for clinical survey using validated measures. Disease-specific and generic questionnaires including the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Scoliosis Research Society-24 questionnaire (SRS-24), approach-related morbidity questionnaire (ArM) and SF-36 in terms of the normalized physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS).

Surgical technique

Mature patients with intractable back pain and adolescents with unacceptable cosmetic deformity or evidence of progressive thoracic or thoracolumbar SK were offered corrective surgery if curve size exceeded 60° and 30°, respectively. Before surgery, patients had MRI scans to exclude disc herniation and intraspinal pathology, pulmonary function analysis, a neurologist consultation and clinical photography (Fig. 4). All patients were treated with AR/PSF using pedicle screws only and iliac bone grafts. For AR, patients with thoracic SK were operated on in a left-sided lateral decubitus position using an open lateral thoracotomy with excision of one rib, usually one level below the uppermost disc to be released and two levels above the apex of the kyphosis. Patients with a thoracolumbar SK had a thoracolumbophrenotomy. Discs were removed using a luer, rongeur and curettes. The anterior longitudinal ligament was cut while the posterior ligament was left intact. At the apex and distal vertebrae, corticocancellous blocks were packed into the disc space, while rib grafts were packed at proximal levels. Thoracic drains were removed on day 3–4 postoperatively and patients were mobilized in a cast until PSF 1 week later. The posterior technique is summarized in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4.

The clinical case example with MRI highlights typical features of Scheuerman kyphosis including vertebral wedging, anterior disc collapse and endplate irregularities. Left and middle images show preoperative thoracic kyphosis in an 18-year-old male patient, which is aggravated by bending forward. Follow-up photograph at 25 months shows the clinical result

Fig. 5.

Posterior surgical technique: usually the end level of kyphosis is selected as the upper instrumented vertebra (UIV). The vertebra above the first disc revealing lordotic wedging is usually selected as the lowest instrumented vertebra (LIV). The selection of LIV also addresses the concerns of increased biomechanical stress at the thoracolumbar junction. Thus, if there were concerns regarding fusion stopping at T12 or L1, the latter was selected as LIV [2]. Midline exposure was extended to the tips of the transverse processes following a posterior release including facet resection, and interspinous ligament resection pedicle screws were placed by free-hand technique using probes and an image intensifier before pedicle screw insertion (the number of screws placed depended on the attending surgeon; Fig. 1). A few patients displayed spontaneous fusion of facet joints and posterior elements indicating Ponte type of osteotomies. a Rods are inserted in a proximal to distal direction using a cantilever technique with a rod persuader slowly distributing correction forces, bringing about kyphosis reduction. b Two to three rounds of periapical segmental compression complete the correction process. c Final unilateral compression can address additional scoliotic deformity—note, the upper screw is protected by a rod holder to prevent loosening. d Clinical assessment of final kyphosis with rod holders fixed to the ends of the rods. e Final assembled screw–rod system with local bone graft and corticocancellous chips from the iliac crest

After PSF, patients were mobilized on day 2 and wore a thoracolumbar orthosis for 4 months. Follow-up was scheduled at 6, 12 and 24 months. For PSF, a rigid third-generation pedicle screw–rod system with 5.5 mm diameter (XIA-2, Stryker, France) was used in 73 patients (65.8 %) and a semi-rigid pedicle screw system with a 4.0 mm threaded rod (USIS, Ulrich, Germany) in 38 patients (34.2 %).

Statistical analysis

Cross-tabulation tables were computed and analyzed using Fisher’s exact test as well as Pearson’s test. ANOVA and repeated measures ANOVA with one fixed factor were performed with two-sided Fisher’s LSD tests as corresponding post hoc tests. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed to analyze the relationship between two continuously and approximately normally distributed variables. Two-sided, unpaired Student’s t tests were applied to compare the variables in two independent groups. A bivariate linear regression model was set up to evaluate the relationship between the postoperative kyphosis (Fusion-Cobb) as dependent and preoperative kyphosis and kyphosis on bending radiographs (best of traction- and HE-radiograph) as independent variables. Data were checked for outliers and normality, and correlation coefficients and coefficient of determination were computed. Regression coefficients were tested for significance. The regression model was tested in an independent test sample (i.e., data were not used for construction of the regression model) of a consecutive series of ten patients with SK treated in 2011 using AR/PSF. A p value <5 % indicated a statistically significant correlation or difference. All analyses were carried out using STATISTICA 10.0 (Statsoft, Chicago/USA).

Results

Sample characteristics

Institutional database review revealed 115 patients with AR/PSF. 111 patients (96.5 %) had complete radiographic sets eligible for analysis. The sample included 74 males (67 %) and 37 females (33 %). Their age was 23.6 ± 10.8 years (range 12–60 years) and average follow-up 23.5 months (range 6–122 months). Six patients (5.4 %) had one-stage AR/PSF and 105 patients (94.6 %) had two-staged surgery. The length of AR was 7.6 ± 1.3 levels (range 5–11 levels), and length of PSF was 8.1 ± 1.3 levels (range 3–11 levels). The majority of patients had instrumentation proximal from T4 (36 %) or T5 (32.4 %) and distal to T12 (21.6 %) or L1 (57.7 %). The first-lordotic disc was located between T11 and L4, at L1–L2 in 66 patients (59.5 %) and T12-L1 in 20 (18 %). The difference between the LIV and the vertebra above the first lordotic disc was 0.1 ± 0.5 levels (range −2 to 2; median: 0).

Radiographic results

Correction

The preoperative Fusion-Cobb was 67.2 ± 12.2° (range 38–96°) and postoperative 37.3 ± 15.6° (range −4 to 76°) showing a significant correction of 30.1 ± 13.5° (range −5 to 65°; p < 0.0001) equaling 45.4 ± 21.4 % (range −10 to 106.7 %). Correction per level instrumented was 3.8 ± 1.9° (range −0.5 to 10°). At follow-up, Fusion-Cobb was 38.5 ± 14.8° (range 0–77°) showing a slight, but non-significant (p = 0.4) loss of correction by 0.7 ± 6.1° (range −23 to 18°). The degree of correction at follow-up was 28.9 ± 13.4° (range −3 to 65°) equaling 43.4 ± 20.8 % (range −5.7 to 100 %). Statistical analysis showed that correction (%/°) significantly depended on preoperative flexibility (r = 0.4/r = 0.7) and decreased with patients’ age (p < 0.05, r = −0.3). Although there was only a slight loss of correction until follow-up, there was a significant correlation between the loss of correction and degree of correction at index surgery (p = 0.04, r = −0.3), indicating increased loss with higher initial correction. The main radiographic findings are listed in Table 1 and Fig. 6. Summarizing, after correction of thoracic and thoracolumbar SK a mean TK of 44° and LL of 55° was achieved and both displayed a significant interrelation (r = 0.5, p < 0.05), indicating compensatory lumbar adjustments for the amount of thoracic and thoracolumbar correction.

Table 1.

Summary of main radiographic results (in°) in 111 patients treated for Scheuermann’s kyphosis

| Radiographic parameter | Preop | Postop | Follow-up | Difference between preop to postop | Difference between postop to follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (range) |

Mean ± SD (range) |

Mean ± SD (range) |

Mean | Mean | |

| Fusion-Cobb | 68 ± 12.2 (38–96) | 40.5 ± 15.7 (−4 to 76) | 39.5 ± 14.8 (0–77) | 28.9, p < 0.0001 | 0.7, ns |

| Cobb T4–T12 | 66.3 ± 13.9 (7–90) | 42.5 ± 12.2 (3–72) | 43.7 ± 11.6 (10–72) | 22.3, p < 0.0001 | 0.8, ns |

| Cobb L1–S1 | 66.3 ± 14.4 (0–93) | 51 ± 12.9 (8–82) | 56.2 ± 11.9 (28–86) | 10.3, p < 0.0001 | 6.0, p = 0.009 |

| Cobb T10–L2 | 24.3 ± 18.1 (0–81) | 13.5 ± 9.1 (−7 to 36) | 13.7 ± 9.2 (0–38) | 11.3, p < 0.001 | 0, ns |

| Sacral slope | 34.0 ± 9.1 (11–68) | 33 ± 8.1 (8–51) | 34.0 ± 7.8 (14–56) | 2.8, p = 0.008 | 0.8, p = 0.001 |

| Pelvic tilt | 11 ± 7.8 (−11 to 24) | 11.9 ± 13.4 (−4 to 33) | 12.2 ± 10.5 (−6 to 28) | 1.6, ns | 0.8, ns |

| JKA + 1 | 6.0 ± 7.2 (−4 to 28) | 9 ± 8.5 (−2 to 40) | 12.0 ± 8 (−3 to 38) | 1.7, p < 0.0001 | 2.7, p = 0.04 |

Fig. 6.

Changes in Fusion-Cobb on preoperative, extension/traction, postoperative and follow-up radiographs

Screw density

Screw density was 87.3 ± 12.9 % (range 41.7–100 %). It showed a significant impact on the correction rate (%/°) (p < 0.001, r = 0.3/r = 0.4), but not on clinical outcomes, amount of JKA + 1 or revision rate. Also, statistical analysis showed that screw density was not correlated with the magnitude of preoperative thoracic hyperkyphosis or flexibility of kyphosis (all p > 0.1).

Flexibility

On traction-radiographs, Fusion-Cobb was 45.1 ± 11.7° (range 14–76°), while on HE-radiographs 47.4 ± 16° (range 4–88°) without significant differences. On traction-radiographs, flexibility of Fusion-Cobb was 22.1 ± 10° (range 4–53°) and 32.9 ± 13.7 % (range 7.9–63.2 %). On HE-radiographs flexibility of Fusion-Cobb was 19.6 ± 9.8° (range −2 to 48°) and 30.5 ± 16.6 % (range −2.5 to 91.8 %). The differences between both were not significant. Analysis of the prediction variables for correction of postoperative kyphosis showed that the difference in the Fusion-Cobb on traction-radiographs and on postoperative radiographs was 9.4 ± 11.3° and was smaller when compared with the HE-radiographs. Correlation between Fusion-Cobb on traction-radiographs and the postoperative and follow-up radiographs (r = 0.7 and r = 0.7) was stronger than for the HE-radiographs (r = 0.4 and r = 0.4). The same interdependencies existed for correction and preoperative flexibility (%/°).

The prediction model revealed that preoperative kyphosis (p = 0.03) and kyphosis on traction/extension (p = 0.000004) are significant prediction variables. The multiple correlation coefficient was R = 0.63 (p < 0.000001). An illustration of the model with the regression equation is shown in Fig. 7. Application of the equation to the sample showed that the difference between predicted postoperative kyphosis and postoperative kyphosis averaged 0.2° based on traction-radiographs and 2.2° when data from hyperextension views were used.

Fig. 7.

Prediction model for postoperative kyphosis based on a linear regression model with two predictor variables. The regression equation is: postop kyphosis = −8.8 + 0.28*preop kyphosis + 0.58*preop kyphosis traction/extension, R = 0.63 (p < 0.000001). The model illustrates that the postoperative kyphosis depends, by similar degrees, on the preoperative curve size and curve flexibility. Hence, reporting the preoperative curve size is not sufficient when comparing different treatment concepts!

The performance of the prediction model in clinical practice was tested by applying the regression model to a series of ten consecutive patients (cross-validation) with a mean age of 21.3 years, which included five female and five male patients. The independence test showed that differences between actual postoperative kyphosis and predicted kyphosis based on preoperative bending radiographs averaged −8.8°.

Scoliosis

Preoperative scoliosis was present in 26 patients (23.4 %) and in 5 patients (4.5 %) postoperatively and at follow-up. It significantly reduced flexibility on traction-radiographs and the degree of correction of TK (p = 0.03/p = 0.03) and Fusion-Cobb (p = 0.03/p = 0.01).

PJK

In 60 patients (54.1 %), the upper thoracic spine could be assessed accurately on preoperative and follow-up radiographs. Preoperative JKA + 1 was 7.7 ± 7.3° (range −4 to 28°), postoperative 11.5 ± 8.5° (range −2 to 40°) and follow-up 14.7 ± 8° (range −3 to 38°). The differences between preoperative to postoperative (p < 0.0001) and postoperative to follow-up (p = 0.04) were significant. The vertebra selected as UIV had no impact on the degree of JKA + 1. Patients with increased postoperative JKA + 1 had an elevated risk for revision surgery (p = 0.049), while patients with revision surgery had decreased outcomes in terms of SRS-24 (p = 0.006/p = 0.004), ArM (p = 0.001/p = 0.0008) and ODI (p = 0.003/p = 0.0004). Preoperative JKA + 1 significantly correlated with PI (r = 0.4, p < 0.05), number of levels fused (r = 0.4, p < 0.05) and postoperative loss of correction (r = −0.3, p < 0.05). Preoperative JKA + 1 is a regional spinal parameter. Hence, the interdependency with the preoperative PI (r = 0.5, p < 0.05) is emphasized. Follow-up JKA + 1 was correlative with the PI (r = 0.4, p < 0.05, valid n = 37). The number of levels fused (r = 0.4, p < 0.05), postoperative loss of correction (°) (r = −0.4, p < 0.05) and Fusion-Cobb (r = −0.3, p < 0.05) showed significant impact on JKA + 1. It was also correlative with the difference between the predicted lumbar lordosis L1–S1 and the follow-up lumbar lordosis (r = −0.4, p < 0.05).

Two patients (1.8 %) had a symptomatic DJK requiring revision once.

Spino-pelvic balance

Interrelations between the pelvic and spinal parameters were maintained in the SK patients throughout treatment. PI was 46 ± 10.8° (range 28–69°). Preoperatively and at follow-up, there was a strong correlation between the SS and LL (r = 0.7 and r = 0.9, p < 0.05), and the correlation between the SS and PI remained high (r = 0.5/r = 0.6, p < 0.05) as between the PI and PT (r = 0.5/r = 0.7, p < 0.05).

Clinical outcomes

Patients were stratified as to whether they responded to clinical follow-up invitation using validated measures (Group B) or not (Group A). 49 patients (44.1 %) were allocated to Group B and 62 (55.9 %) to Group A. Follow-up of Group B was 59.2 ± 33 months. Group B patients were older than Group A (p = 0.01) and had longer follow-up, but there were no differences concerning gender distribution, complication rate and need for revision or subsequent surgery, preoperative scoliosis, JKA + 1 and other radiographic parameters. Older patients and patients with a longer follow-up had statistically decreased outcomes in terms of SRS-24 (r = −0.3/r = −0.5), ArM (r = 0.5/ns) and ODI (r = 0.5/r = 0.5). Thus, Group B generally underestimates the general outcome of patients rather than biasing it.

The SRS-24 sum score was 91.4 ± 15.7 (range 46–110 patients), ODI 6.4 ± 7.7 % (range 0–32 %) and ArM 19.2 ± 23.7 % (range 0–72.5 %). The SF-36 PCS was 48.6 ± 9.7 (range 23.3–57) and MCS was 48.8 ± 11.3 (range 20.1–62.6). Statistical analysis revealed a strong correlation between the SRS-24 and ODI (r = 0.9, p < 0.05), SRS-24 and ArM (r = 0.7, p < 0.05), and between ODI and ArM (r = 0.8, p < 0.05). Concerning outcomes, statistics showed a significant negative correlation for increased fusion length and SRS-24 self-image scores (r = −0.5, p < 0.05). The degree of correction and other radiographic measures had no impact on clinical outcome measures. 42 patients (85.7 %) responded that they would undergo the same treatment again, 3 (6 %) were not sure and 4 (8 %) would rather not, or definitely not, undergo the same procedure again. Clinical examples are illustrated in Figs. 1, 4 and 8.

Fig. 8.

A 15-year-old patient with thoracic Scheuermann’s hyperkyphosis. Preoperative full-standing lateral radiograph shows kyphosis of 87° that corrects to 58° on traction-radiograph. Follow-up radiograph at 26 months revealed solid union and maintenance of correction at 44°, using a modern all-pedicle screw construct

Complications

22 patients experienced a minor complication. No patient sustained a neurovascular injury or died. 21 patients (18.9 %) had revision surgery. Six patients (5.4 %) had a minor revision surgery for superficial wound infection or delayed wound healing needing irrigation and debridement. Another 13 patients (12 %) had a significant revision surgery. Indications for rigid modern pedicle screw–rod versus semi-rigid screw–rod systems were skin breakdown above a screw head (1 vs. 0 patient), construct failure with rod fracture (0 vs. 3 patients), screw loosening (0 vs. 3 patients) and screw dislocation (3 vs. 2 patients) indicating that revision instrumentation and fusion was required in five patients (4.5 %) with non-union. Two had non-union in the lower foundation, and three in the upper fusion levels. Summarizing, the major complication rate was 5.4 % with the rigid modern system and 21.1 % with the semi-rigid system. Neither the presence of scoliosis nor the level of the LIV, or the difference between the LIV and the first lordotic disc, impacted revision rates. Patients undergoing revision had diminished SRS-24 scores (73.8 % vs. 93.9 %, p = 0.004), higher ArM (53.1 % vs. 15.3 %, p = 0.0008) and ODI (15.6 % vs. 5.2 %, p = 0.004). Statistical analysis did not reveal significant differences regarding the rate of significant revision in Group A (11.6 %) compared to Group B (11.9 %).

Discussion

The current study hoped to provide better evidence for the efficacy of AR/PSF. The patients’ characteristics were comparable to those of previous studies (Table 2) and the results concur with those of other authors [12, 14, 28, 31], confirming that in terms of safety, correction, fusion rate and clinical outcome AR/PSF is an efficient strategy conferring reproducible results as well as several advantages. The mean correction of Fusion-Cobb was 30° and correction per instrumented level 4°. The amount of correction largely depended on preoperative curve size, flexibility and target kyphosis. With deformity surgery in adolescents, there seems to be consensus that lumbar motion and function decrease, while morbidity and disability increase with the number of lumbar levels fused [32–35]. With most patients having LIV at the first-lordotic disc in our study, the number of levels fused could be limited to eight on average, indicating a mobile lumbar spine in most patients. In other studies, fusion length averaged 11 [36], 12 [29] and 13 levels [28] or was not reported [3, 8]. There is ongoing discussion regarding the appropriate end level to spare motion segments while lowering the risk of PJK and DJK [37]. Regarding UIV, there seems to be agreement concerning inclusion of at least the proximal end vertebra [24]. Hamzaoglu [38] recommended inclusion of the proximal EV and EV + 1, based on the rationale that the EV should be the last proximal vertebra sustaining correction forces. Concerning LIV selection, several authors recommend instrumentation at least one level below the first-lordotic disc, particularly if posterior-only correction is anticipated [13–15, 26, 28, 39, 40]. This means two levels more than reported in the current study. Denis [3], Ning and Lenke [40, 41] and Arlet [40] recommended inclusion of the vertebra touched by the C7-SPL called ‘sagittal stable vertebra’ which is usually one to two levels lower than in the current study. With application of AR/PSF and the use of pedicle screws only, stopping fusion at the first lordotic disc on average was shown to be efficient. Only one of our SK patients required revision for DJK, one to two motion levels were spared compared to other concepts. Nevertheless, with posterior-only fusion, selection of LIV below the first-lordotic disc seems appropriate. Possibly one [12, 14], two [26] or more levels should be the subject of comparative studies using pedicle screws only.

Table 2.

Review of literature on radiographic outcomes of surgical correction of Scheuermann’s kyphosis (minimum sample size n = 20)

| Author | Years | n | Technique | Kyphosis preop | Kyphosis postop | Kyphosis follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradford et al. [1] | 1975 | 22 | PSF | 72 | 31 | 47 |

| Griss et al. [4] | 1978 | 20 | PSF | 52 | 24 | 36 |

| Taylor et al. [6] | 1979 | 27 | PSF | 72 | 40 | 46 |

| Bradford et al. [17] | 1980 | 24 | ASF & PSF | 77 | 41 | 47 |

| Speck [18] | 1986 | 61 | PSF | 77 | 38 | 42 |

| 7 | ASF | 82 | 44 | 45 | ||

| Lowe [13] | 1987 | 24 | ASF & PSF | 85 | 44 | 50 |

| Sturm et al. [20] | 1993 | 30 | PSF | 72 | 33 | 37 |

| Lowe [14] | 1994 | 32 | ASF & PSF | 86 | 41 | 47 |

| Ferreira-Alves et al. [22] | 1995 | 38 | PSF | 68 | 39 | 43 |

| Papagelopoulos et al. [24] | 2001 | 21 | PSF | 75 | 37 | 42 |

| Hosman et al. [8] | 2002 | 16 | PSF | 77 | 52 | 56 |

| 17 | ASF & PSF | 80 | 51 | 53 | ||

| Poolman et al. [26] | 2002 | 23 | ASF & PSF | 70 | 39 | 55 |

| Lim et al. [27] | 2004 | 26 | ASF & PSF | 83 | 46 | 51 |

| Herrera-Soto et al. [28] | 2005 | 19 | ASF & PSF | 85 | 44 | 45 |

| Johnston et al. [36] | 2005 | 19 | ASF & PSF | 80 | 50 | 38 |

| Lee et al. [29] | 2006 | 18 | PSF | 84 | 38 | 40 |

| 21 | ASF & PSF | 89 | 52 | 54 | ||

| Jansen et al. [10] | 2006 | 30 | ASF & PSF | 80 | 47 | na |

| Lonner et al. [30] | 2007 | 42 | ASF & PSF | 82 | 53 | 56 |

| 36 | PSF | 74 | 40 | 46 | ||

| Koptan et al. [23] | 2008 | 16 | PSF | 86 | 45 | na |

| 17 | ASF | 80 | 39 | na | ||

| Denis et al. [3] | 2009 | 52 | ASF & PSF | 78 | 45 | 49 |

| 15 | PSF | |||||

| Current study | 2012 | 111 | ASF & PSF | 67 | 37 | 39 |

| 769 | 77° | 42° | 46° |

Using a modern rigid pedicle screw–rod construct in the majority of patients with a screw density of 87 %, our loss of correction was small (~1°). A study by Clements [42] showed that screw density has a significant bearing on major curve correction in scoliosis (r = 0.3, p = 0.001). The current study in SK confirmed the results showing that the degree of correction correlated with the number of screws placed: periapical segmental compression increases forces that can be directed toward and controlled at each segment, while the deflection forces of the rod acting on the inserted screws are distributed over a larger area when choosing segmental instrumentation.

In SK correction reconstruction of a physiologic alignment is decisive. Lonner [30] reported that the presence of postoperative PJK correlated with TK and with PI. In scoliosis, greater decrease of TK significantly correlated with PJK (27 %) [43]. In our study, JKA + 1 resembling the amount of PJK was related to PI, TK and Fusion-Cobb. Changes at the junctional level are impacted by individual spino-pelvic morphology and determined by the individually predetermined ideal sagittal alignment. Accordingly, overcorrection of thoracic hyperkyphosis will result in increased PJK. This in turn might cause implant loosening at the UIV and loss of correction, due to the upper non-instrumented thoracic spine and lumbar spine moving to balance the spino-pelvic parameters [3, 8, 14, 24, 30, 40]. Overcorrection is more likely to occur in flexible SK, causing adjacent segment problems. In other studies with longer fusions, it largely increased the risk for DJK [8, 14, 40]. In our study, increase of JKA + 1 was correlated with higher risk for a revision surgery, which in turn was related to poorer clinical outcomes. Similarly, in a study by Denis [3], the presence of PJK and DJK was a risk factor for revision surgery (20 and 50 %). The study emphasized that the restoration of spino-pelvic and spinal balance is of the greatest importance—not the degree of kyphosis correction.

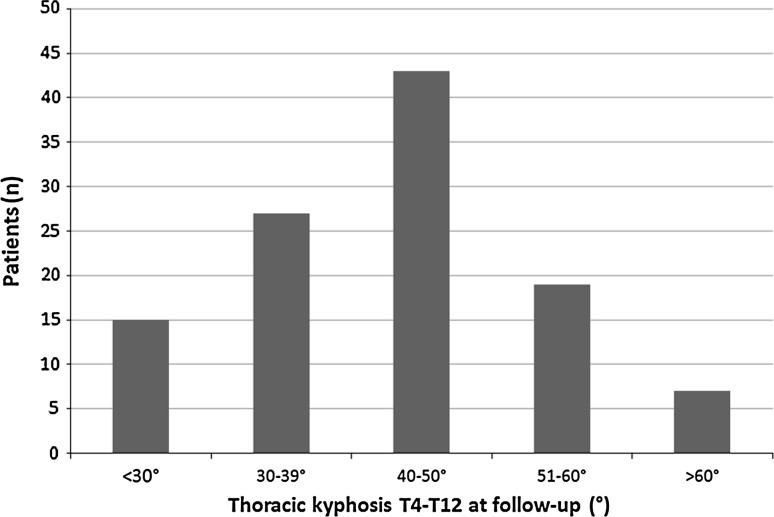

Undercorrection with a persisting thoracic hyperkyphosis will usually result in compensatory lumbar hyperlordosis, which can be the source of accelerated degeneration and complaints in the long term. Therefore, appropriate reconstruction of kyphosis is indicated. With a mean TK of 44° and LL of 55° in perspective of a PI of 46°, this goal was achieved in our patients as shown in Fig. 9, summarizing the distribution of final TK in our patients. When a TK of ~45° (40–50°) is accepted as a desirable target kyphosis [8, 14, 26, 44], then AR/PSF resulted in overcorrection in some patients, particularly when a threaded screw–rod system was used. On the other hand, with the techniques described a few patients also had undercorrection. Screw density was shown to have an impact on the correction rate, indicating that in patients with most rigid deformities, as seen in the few patients with undercorrection in the current series, more aggressive antero-posterior releases, compression and high screw density rate are needed to achieve target kyphosis.

Fig. 9.

Distribution of thoracic kyphosis T4–T12 on follow-up radiographs as measured on full-standing lateral radiographs. Kyphosis <30° and >60°

The literature does not provide sufficient evidence to delineate when to use AR/PSF, PSF-only or when to apply distinct osteotomy techniques, to achieve the ideal target kyphosis. In our review of literature (Table 2) which included a total of 727 patients, with an average sample size of 29 and mean age of 20 years, three studies reported on clinical outcomes using validated measures. Flexibility data were reported only by Koptan (in %) [23], Lee (in %) [29], Johnston (in %) [36], Herera-soto (in°) [28] and Hosman (in°) [8]. There has been no study yet comparing both strategies based on comparable preoperative kyphosis and flexibility in a sufficiently large sample. Our study confirmed that kyphosis correction is dependent on preoperative curve flexibility, with better kyphosis correction in traction-radiographs than HE-radiographs. On average, postoperative correction was 9° better than preoperative curve size on traction-radiographs.

A bivariate regression analysis generated an equation with a prediction accuracy of 0.2–2°. Its clinical application, however, on an independent test sample, revealed a difference of −8.8°. Equations as reported for prediction of scoliosis correction or prediction of sagittal balance [45, 46] were not tested in independent samples. However, the current study stressed that this is decisive to study the clinical value of an equation. Deviation of the differences between predicted and achieved postoperative kyphosis confirmed that the degree of SK correction depended on the preoperative flexibility and also on other variables, such as the aggressiveness of anterior and posterior release and screw density. Also, as illustrated in Fig. 9, a few patients in the original sample had overcorrection to <30°, which was avoided in subsequent SK surgeries in the authors’ institution. Nevertheless, high prediction of the bivariate model in the original group demonstrated the impact preoperative flexibility had on the postoperative degree of correction. Results indicate that any comparison of posterior-only versus ASR/PSF has to be based on similar preoperative measures.

With a mean correction of 30°, TK of 44° at follow-up and a mean of eight levels fused, the overall clinical outcome in the SK patients was good. Mean ODI was only 6 % and within normal range [47]. SRS-24 sum score and SF-36 PCS were high with 91 and 49, respectively. Clinical outcomes did not correlate with the degree of curve correction—as in a study by Poolman [26]. This was most likely related to the fact that the amount of correction needed to achieve target kyphosis varied in each patient. Notably, similar to another study on adolescent idiopathic scoliosis undergoing anterior open transthoracic correction [48], average ArM was low (19 %). However, age had a significant correlation with ArM. While ArM was 8 % in patients aged ≤20 years, it averaged 24 % in patients aged >20 years, which was still modest on average. Likewise, Coe [11] and Tribus [16] have shown that the incidence of complications in SK surgery increases with patients’ age [11, 16]. The selection of AR should be discussed critically in older patients in terms of its impact on curve correction, salvage of fusion levels and ArM.

A treatment is only as good as its treatable complications. In the current study, there was no neurological injury. Results showed that occurrence of complications and need for revision surgery (17 %) had a significant impact on clinical outcomes. The main complications requiring revision were not related to the anterior approach, but they were related to the posterior wound, a consequence of implant loosening, construct failure or non-union with the semi-rigid threaded rod system (which is not used anymore), or related to a high JKA + 1, particularly in cases with overcorrection, mirroring observations of previous studies [3, 8, 14, 49]. The complication rate was 5 % using a modern rigid instrumentation and 21 % using the former semi-rigid system. The findings confirmed that with the development of modern instruments and implants, reduction of complications has been possible over time.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bradford DS, Moe JH, Montalvo FJ, Winter RB. Scheuermann’s kyphosis. Results of surgical treatment by posterior spine arthrodesis in twenty-two patients. JBJS-A. 1975;57:439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ascani E, Rosa G. Scheuermann kyphosis. New York: Raven Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denis F, Sun EC, Winter RB. Incidence and risk factors for proximal and distal junctional kyphosis following surgical treatment for Scheuermann kyphosis: minimum five-year follow-up. Spine. 2009;34:E729–E734. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ae2ab2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griss P, von Andrian-Werburg HF. Results of corrective surgery in juvenile kyphosis (Scheuermann’s disease) using Harrington’s compressive rods. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1978;91:113–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00378893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwab F, Patel A, Ungar B, Farcy J-P, Lafage V. Adult spinal deformity—postoperative standing imbalance. Spine. 2010;35:2224–2231. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ee6bd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor TC, Wenger DR, Stephen J, Gillespie R, Bobechko WP. Surgical management of thoracic kyphosis in adolescents. JBJS-A. 1979;61:496–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denis F. Spinal instability as defined by the three-column spine concept in acute spinal trauma. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1983;189:65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosman AJ, Langeloo DD, de Kleuver M, Anderson PG, Veth RP, Slot GH. Analysis of the sagittal plane after surgical management for Scheuermann’s disease: a view on overcorrection and the use of an anterior release. Spine. 2002;27:167–175. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200201150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lonner BS, Murthy SK, Boachie-adjei O. Single-staged double anterior and posterior spinal reconstruction for rigid adult spinal deformity: a report of four cases. The Spine J. 2005;5:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen RC, van Rhijn LW, van Ooij A. Predictable correction of the unfused lumbar lordosis after thoracic correction and fusion in Scheuermann kyphosis. Spine. 2006;31:1227–1231. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000217682.53629.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coe JD, Smith JS, Berven S, Arlet V, Donaldson W, Hanson D, Mudiyam R, Perra J, Owen J, Marks MC, Shaffrey CI. Complications of spinal fusion for Scheuermann kyphosis—a report of the scoliosis research society morbidity and mortality committee. Spine. 2009;35:99–103. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c47f0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe G, Breton G. Evidence based medicine. Anal Scheuermann Kyphosis. 2007;32:S115–S119. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181354501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe TG. Double L-rod instrumentation in the treatment of severe kyphosis secondary to Scheuermann’s disease. Spine. 1987;12:336–341. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198705000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe TG, Kasten T. An analysis of sagittal curves and balance after Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation for kyphosis secondary to Scheuermann’s disease. A review of 32 patients. Spine. 1994;19:1680–1685. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe TG. Scheuermann’s disease. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:475–487. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(05)70100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tribus CB. Scheuermann’s kyphosis in adolescents and adults: diagnosis and management. J Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:36–43. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradford DS, Ahmed KB, Moe JH, Winter RB, Lonstein JE. The surgical management of patients with Scheuermann’s disease: a review of twenty-four cases managed by combined anterior and posterior spine fusion. JBJS-A. 1980;62:705–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speck GR, Chopin DC. The surgical treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis. JBJS-Br. 1986;68:189–193. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B2.3958000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsirikos AI, Jain AK. Scheuermann’s kyphosis; current controversies. JBJS-Br. 2011;93:857–864. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B7.26129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sturm PF, Dobson JC, Armstrong GW. The surgical management of Scheuermann’s disease. Spine. 1993;18:685–691. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamzaoglu A, Talu U, Tezer M, Mirzanli C, Domanic U, Goksan SB. Assessment of curve flexibility in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2005;30:1637–1642. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000170580.92177.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferreira-Alves A, Resina J, Palma-Rodrigues R. Scheuermann’s kyphosis. The Portuguese technique of surgical treatment. JBJS-Br. 1995;77:943–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koptan WM, Elmiligui YH, Elsebaie HB. All pedicle screw instrumentation for Scheuermann’s kyphosis correction: is it worth it? Spine J. 2009;9:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papagelopoulos PJ, Klassen RA, Peterson HA, Dekutoski MB. Surgical treatment of Scheuermann’s disease with segmental compression instrumentation. CORR. 2001;386:139–149. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200105000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glassmann SD, Hamill CL, Bridwell KH, Schwab FJ, Dimar JR, Lowe TG. The impact of perioperative complications on clinical outcome in adult deformity surgery. Spine. 2007;32:2764–2770. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815a7644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poolman RW, Been HD, Ubags LH. Clinical outcome and radiographic results after operative treatment of Scheuermann’s disease. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:561–569. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim M, Green DW, Billinghurst JE, Huang RC, Rawlins BA, Widmann RF, Burke SW, Boachie-Adjei O. Scheuermann kyphosis: safe and effective surgical treatment using multisegmental instrumentation. Spine. 2004;29:1789–1794. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000134571.55158.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrera-Soto JA, Parikh SN, Al-Sayyad MJ, Crawford AH. Experience with combined video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) anterior spinal release and posterior spinal fusion in Scheuermann’s kyphosis. Spine. 2005;30:2176–2181. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000180476.08010.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SS, Lenke LG, Kuklo TR, Valente L, Bridwell KH, Sides B, Blanke K. Comparison of Scheuermann kyphosis correction by posterior-only thoracic pedicle screw fixation versus combined anterior/posterior fusion. Spine. 2006;31:2316–2321. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000238977.36165.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lonner BS, Newton P, Betz R, Schaf C, O’Brien M, Sponseller P, Lenke L, Crawford A, Lowe T, Letko L, Harms J, Shufflebarger H. Operative management of Scheuermann’s kyphosis in 78 patients: radiographic outcomes, complications, and technique. Spine. 2007;2007:2644–2652. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815a5238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Jonge T, Illes T, Bellyei G. Surgical correction of Scheuermann’s kyphosis. Int Orthop. 2001;25:70–73. doi: 10.1007/s002640100232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilk B, Karol LA, Johnston CE, Colby S, Haideri N. The effect of scoliosis fusion on spinal motion: a comparison of fused and nonfused patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2006;31:309–314. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000197168.11815.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Baldus C, Blanke K, Schonecker PL. Ability of Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation to preserve distal lumbar motion segments in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:339–350. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199306040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Betz RR, Harms J, Clements D, Lenke L, Low T, Jeszensky D, Shufflebarger HL, Beele B. Comparison of anterior and posterior instrumentation for correction of adolescent thoracic idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 1999;24:225–239. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199902010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marks M, Newton PO, Petcharaporn M, Bastrom TP, Shah S, Betz R, Lonner B, Miyanji F (2011) Postoperative segmental motion of the unfused spine distal to the fusion in 100 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. Spine e-pub 2011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Johnston CE, Elerson E, Dagher G. Correction of adolescent hyperkyphosis with posterior-only threaded rod compression instrumentation: is anterior spinal fusion still necessary? Spine. 2005;30:1528–1534. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000167672.06216.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho K-J, Lenke L, Bridwell KH, Kamiya M, Sides B. Selection of the optimal distal fusion level in posterior instrumentation and fusion for thoracic hyperkyphosis. Spine. 2009;34:765–770. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819e28ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamzaoglu A, Ozturk C, Korkmaz FM, Karatoprak O, Enercan M, Zezer M. A new technique to prevent proximal junctional kyphosis in the surgical treatment of Scheuermann disease. Vienna: IMAST; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otsuka NY, Hall JE, Mah JY. Posterior fusion for Scheuermann’s kyphosis. CORR. 1990;251:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arlet V, Schlenzka D. Scheuermann’s kyphosis: surgical treatment. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:817–827. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0750-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ning Y, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Koester L. How to determine optimal fusion levels of Scheuermann’s kyphosis. Louisville: SRS annual meeting; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clements DH, Betz RR, Newton PO, Rohmiller M, Marks MC, Bastrom T. Correlation of scoliosis curve correction with the number and type of fixation anchors. Spine. 2009;34:2147–2150. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181adb35d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim YJ, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Kim J, Cho SK, Cheh G, Yoon J. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis after 3 different types of posterior segmental spinal instrumentation and fusions—incidence and risk factor analysis of 410 cases. Spine. 2007;32:2731–2738. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815a7ead. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winter RB, Lonstein JE, Denis F. Sagittal spinal alignment: the true measurement, norms, and description of correction for thoracic kyphosis. J Spinal Disord. 2009;22:311–314. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31817dfcc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lafage V, Bharucha NJ, Schwab F, Hart RA, Burton D, Boachie-Adjei O, Smith JS, Hostin R, Shaffrey C, Gupta M, Akbarnia BA, Bess S. Multicenter validation of a formula predicting postoperative spinopelvic alignment. JNS. 2012;16:15–21. doi: 10.3171/2011.8.SPINE11272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abel MF, Herndon SK, Sauer LD, Novicoff WM, Smith JS, Shaffrey CI, Spinal Deformity Study Group Selective versus nonselective fusion for idiopathic scoliosis: does lumbosacral takeoff angle change? Spine. 2011;36:1103–1112. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f60b5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine. 2000;25:2940–2953. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zenner J, Koller H, Hempfing A, Hutter J, Hitzl W, Resch H, Tauber M, Meier O, Ferraris L. Approach-related morbidity in transthoracic anterior spine surgery: a clinical study and review of literature. Coluna Columna. 2010;9:72–84. doi: 10.1590/S1808-18512010000100014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arlet V. Anterior thoracoscopic spine release in deformity surgery: a meta-analysis and review. Eur Spine J. 2000;9(Suppl 1):S17–S23. doi: 10.1007/s005860000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]