Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether an innovative graphical tool for accurate measurement of individual surgeon performance metrics, adjusted for both surgeon-specific and patient-specific factors, significantly alters interpretation of performance data.

Design

Retrospective analysis of all total knee replacements (TKRs) conducted at the host institution between 1996 and 2009. The database was randomly divided into training and testing datasets. Using multivariate generalised estimating equation regression models, the training dataset enabled generation of patient-risk and surgeon-experience adjustment factors. To simulate prospective monitoring of individual surgeon outcomes, the testing dataset was mapped on control charts. Weighted κ statistics were calculated to measure the agreement between patient-risk adjusted and fully adjusted control charts.

Setting

Tertiary care academic hospital.

Participants

All patients undergoing TKR at the host institution 1996–2009.

Main outcome measure

Operative efficiency.

Results

5313 procedures were analysed. Adjusted control charts were generated using a training dataset comprising 3756 procedures performed by 13 surgeons. The operative time gradually declined by 121 min with 25 years of experience (p<0.0001). Charts were tested by monitoring four other surgeons, performing an average of 389 procedures each. Adjustment for surgeon experience significantly altered the interpretation of operative efficiency (κ=0.29 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.47)), and enhanced assessment of a surgeon's improvement or diminishment in efficiency over time. Specifically, experience adjustment inverted the interpretation of surgeon efficiency from above average to below average, or from improving to declining performance.

Conclusions

Adjustment for surgeon experience is necessary for accurate interpretation of metrics over the course of a surgeon's career. Patient-adjusted and surgeon-adjusted control charts provide an accurate method of monitoring individual operative efficiency.

Keywords: Surgery, Public Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of high-granularity data on over 5000 procedures, across 14 years, performed by 17 surgeons.

Robust statistical demonstration of the effects of adjusting for surgeon-specific factors.

Single centre, retrospective and focused operative time, which although has clear relevance to operative efficiency and financial costs, is not a clear patient-centred outcome.

Introduction

Increasing patient demands, costs and emphasis on safety have led to marked interest in performance tracking of individual healthcare providers.1–5 While the adoption of techniques to monitor surgeons has lagged behind that of providers in other areas of medicine, we are now witnessing the insinuation of such tools into the surgical sphere. In the UK, surgeons have recently been required to publish their individual performance data. There has also been a growing interest, among patients and health authorities, to track surgeons’ individual performance. Two expressed concerns have been that surgeons will be averse to operating on high-risk patients (those demonstrating unfavourable case-mix) and are less likely to accompany junior trainees (those with unfavourable experience) during procedures for fear of poor performance results.1 6–8 Without addressing such concerns, it is possible that publication of performance data may result in unwanted changes in practice, and the generation of inaccurate, inequitable data.

Several methods of individual surgeon performance monitoring have been proposed,9–11 frequently adjusting for patient-specific characteristics, or case mix, including demographics and medical comorbidities. The influence of such characteristics on surgical outcomes has been well explored and acknowledged.12–14 Very recently, the role of surgeon-specific factors such as operative experience and surgical team familiarity, with respect to outcomes, has also been elucidated.15–17

The relative importance of adjusting for both patient-specific and surgeon-specific factors when assessing operative performance has historically been stymied by difficulties in generating research databases of sufficient granularity and robustness to carry out detailed statistical analyses. Such limitations have been ameliorated by the development of large depositories of electronic medical data. Through the parsing of such data, we are now fortunate to have the opportunity to perform inquiries once thought impossible.

While it is important that surgeons are monitored, and is clear that the measurements result in improvements,1 6 it is paramount that the ‘measuring stick’ with which performance is evaluated is accurate. To address the aforementioned confounders of case mix and surgeon experience, we explored the use of patient-adjusted and surgeon-adjusted control charts to permit accurate performance tracking of individual surgeons.

Control charts, a tool initially devised in the manufacturing industry, permit iterative improvements in quality by statistical process control.18 They comprise of mapping a process metric or outcome on a chart with a predetermined benchmark. Upper and lower limits are placed on the chart, typically at two or three SDs from the benchmark value; exceeding these limits indicates an anomalous or unlikely event that is signalled, investigated and when necessary acted on to improve the charted process. In healthcare, they have demonstrated benefit by permitting identification of causes of variation and enabling safety monitoring.19 Control charts have been demonstrated to result in improved health outcomes, efficiency and safety.20 21

We believe that when appropriately adjusted, control charts may offer similar benefits in the sphere of surgical efficiency and performance. Specifically, our aim was to determine whether such a tool, when adjusted for surgeon-specific and patient-specific factors, would significantly alter interpretation of performance data. We present the results of this research endeavour as a proof-of-concept of the potential value of adjusted control charts over more traditional methodologies in performance monitoring.

Methods

Study design and population

Following an institutional review board approval (protocol 2006p000586), we conducted a longitudinal analysis of 5313 knee replacement procedures performed by 17 surgeons at a single academic tertiary care centre (Brigham & Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA) between 1996 and 2009. In order to develop the performance chart independently from the data to be monitored, the database was randomly split into training and testing datasets according to surgeon identity.22 The training dataset included 3756 procedures performed by 13 surgeons and was used to define the baseline parameters of the control charts, including upper and lower limits for the charts, as well as models for case-mix and experience adjustments. The testing dataset included 1557 procedures performed by the four other surgeons; operative time of procedures by each of these surgeons was mapped on control charts developed using the training dataset, to simulate performance monitoring.

Outcome measures and data collection

Data were culled from a combination of electronic medical records, an electronic operative time-tracking application and physician employee databases. Operative time, the primary outcome measurement, was measured in minutes and defined as the time elapsed from skin incision to skin closure. Operative time was used as a proxy for operative efficiency. For each procedure, the length of experience of each participating surgeon was calculated. The operative experience of the attending surgeon was calculated as the difference between the date of the procedure and that of the surgeon's completion of training.

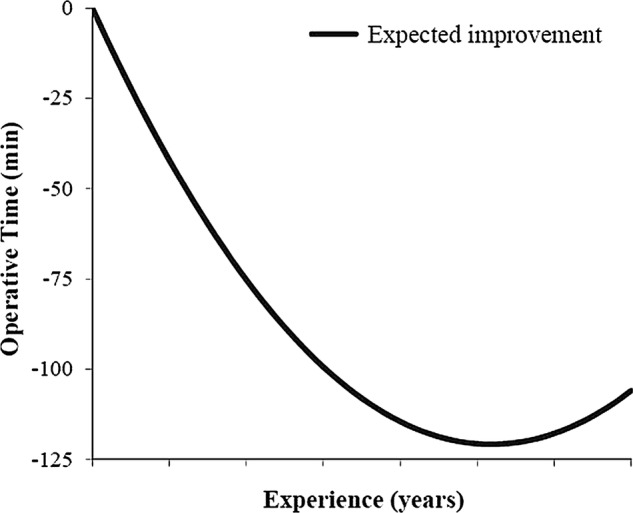

Performance curve modelling and case-mix adjustment

We used the training dataset to determine the adjusted performance curve of surgeons during their career based on a multivariate generalised estimating equation regression model, also taking into consideration the clustering of patients by surgeon.23 Operative time was the outcome of interest, while surgeon experience was the predictor, and patient case mix (patient's age, sex, smoking status and the presence of comorbidities—type II diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder) was considered as a covariate in the final model. We included all available comorbidities from our dataset in the case-mix adjustment model. As the operative time curve may not necessarily be a linear function of surgeon experience, a number of possible shapes of performance curves were tested. In order to obtain the best fitting shape, surgeon's experience was entered as a linear term and a quadratic term in the final model.24 An adjusted performance curve was drawn versus the number of years since surgeon graduation. Also, the reduction in operative time independently associated with the attending surgeon's experience was plotted. Model estimates were obtained using the GENMOD procedure in SAS V. 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA); all tests were two-tailed, and p values<0.05 were considered significant.

Design and comparison of patient-risk-adjusted and fully adjusted control charts

Operative time from procedures in the testing dataset was adjusted using models derived from the training dataset. Operative time was adjusted for patient-risk alone, or for patient-risk and surgeon experience together (fully adjusted). For every surgeon, adjusted outcomes at a given year of experience were calculated as the ratio between the observed and the expected operative time multiplied by the overall mean operative time. Once adjusted, operative time was then plotted on a Shewhart control chart to simulate prospective outcome monitoring for every individual surgeon over the course of his/her career.25 Each data point depicted the surgeon operative time per year since graduation. The central line of the patient-risk-adjusted chart was constant and was determined based on the overall mean operative time, while the central line value of the fully adjusted chart varied and depicted the adjusted performance curve of surgeons as a function of their previous experience that was previously generated from the training dataset. Control and warning limits were set at 3 and 2 SDs around the central line, respectively, to indicate whether a particular surgeon’s performance differed significantly from this goal. The detection of a significantly high or poor performance was defined as a single point outside the control limits, or two of the three successive points between a warning limit and a control limit on the same side of the central line.26 Underperforming surgeons were positioned above the upper limits (ie, longer operative time), while surgeons with unusually good results were below the lower limits (shorter operative time).27

The agreement between patient-risk-adjusted and fully adjusted charts in detecting indicator variations was measured using the weighted Cohen k statistic.28 The positions of the data points for surgeon's individual performance were compared in terms of five ordinal levels based on warning and control limits.

Results

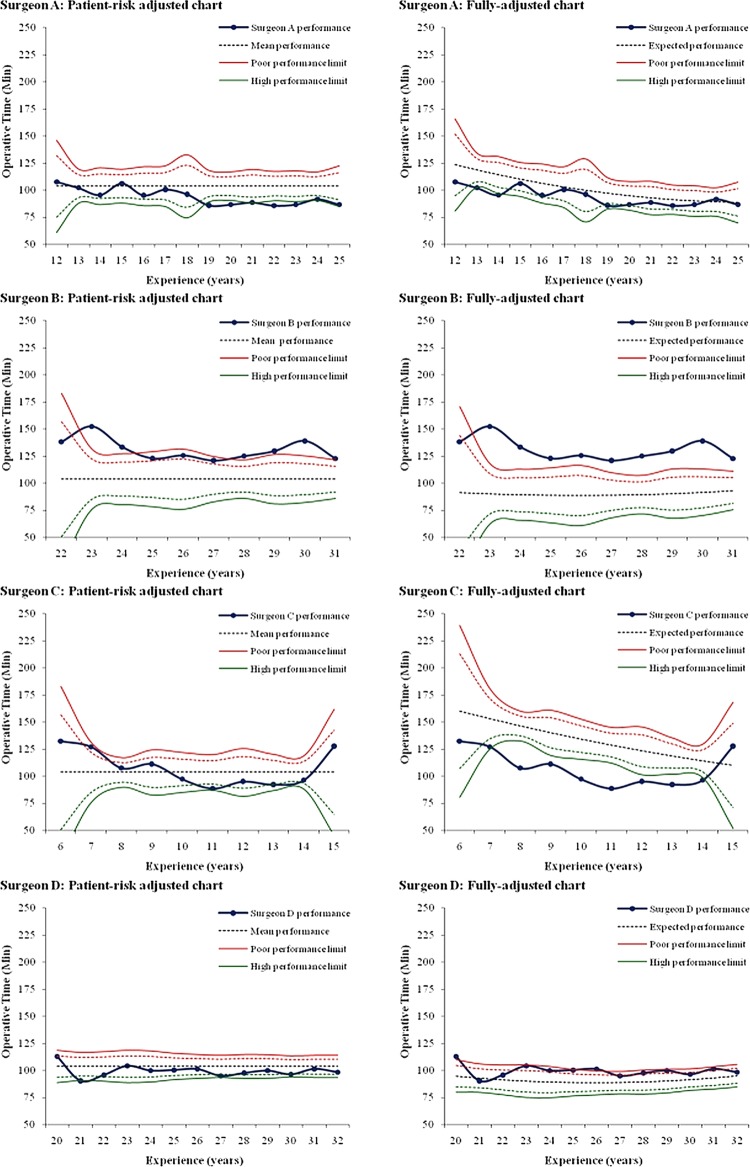

A total of 5313 total knee replacement (TKR) procedures performed by 17 surgeons were analysed. The median surgical experience was 17 years, ranging from 1 to 35 years in practice since graduation. The mean operative time was 109 min (SD 30.3 min). A substantial decline in risk-adjusted operative time was observed over the course of surgeon's career, resulting in a concave-shaped performance curve (p<0.0001, figure 1; to maintain anonymity, the number of years of experience has been removed from the x axis of all figures). Table 1 summarises the surgeon and patient characteristics of the training and testing datasets; table 2 displays the number of procedures performed by each surgeon.

Figure 1.

Performance curve for individual surgeon total knee replacement operative efficiency. The graph illustrates how operative time within the cohort changed with surgeon experience.

Table 1.

Overview of study participants

| Training dataset | Testing dataset | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Attending surgeon | (N=17) | (N=13) | (N=4) |

| Surgeon experience, years, median (Min–Max) | 17 (1–35) | 15(1–35) | 23(6–32) |

| Surgeon volume of cases, median (Min–Max) | 176 (10–1871) | 144(10–1871) | 319(157–761) |

| Surgical cases | (N=5313) | (N=3756) | (N=1557) |

| Patient female gender, N (%) | 3558 (67.0) | 2543 (67.7) | 1015 (65.2) |

| Patient age, years, mean (SD) | 66.2 (11.3) | 65.8 (11.4) | 67.0(11.0) |

| Patient with comorbidity, N (%) | 3388 (63.8) | 2440 (65.0) | 948 (60.9) |

| Number of comorbidities, median (Min–Max) | 1 (0–6) | 1 (0–6) | 1 (0–5) |

| Coronary artery disease, N (%) | 1074 (20.2) | 751 (20.0) | 323 (20.7) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, N (%) | 320 (6.0) | 230 (6.1) | 90 (5.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 858 (16.1) | 636 (16.9) | 222(14.3) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 2196 (41.3) | 1609 (42.8) | 587 (37.7) |

| Obesity, N (%) | 1242 (23.4) | 935 (24.9) | 307 (19.7) |

| Tobacco, N (%) | 814 (15.3) | 590(15.7) | 224(14.4) |

| Operative time, minutes, mean (SD) | 109.2 (30.3) | 103.5 (29.8) | 123.0 (26.9) |

Table 2.

Number of total knee replacements performed by each surgeon

| Attending surgeon | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| 1* | 11 |

| 2* | 61 |

| 3† | 427 |

| 4* | 63 |

| 5† | 157 |

| 6* | 264 |

| 7† | 212 |

| 8* | 184 |

| 9* | 144 |

| 10* | 367 |

| 11* | 66 |

| 12* | 176 |

| 13* | 10 |

| 14* | 59 |

| 15* | 478 |

| 16† | 761 |

| 17* | 1871 |

*Testing dataset.

†Training dataset.

Figure 2 demonstrates the patient-risk-adjusted operative time of four surgeons for TKR with respect to the expected ‘benchmark’ performance curve over time, with slower operative time being placed above the benchmark, indicating a reduced operative efficiency, and faster operative time being placed below the benchmark, indicating an improved operative efficiency. Inspection of each surgeon's performance curve revealed that surgeon A displayed a better operative efficiency than did surgeon B, with a lower operative time. Furthermore, surgeon A's operative efficiency, unlike surgeon B's, was better than expected, demonstrating an operative time below the benchmark performance curve. Surgeons C and D demonstrated similar operative time. With respect to the benchmark performance curve, however, surgeon C performed better than expected, given his low experience, displaying a superior operative efficiency. Surgeon D, relative to the benchmark performance curve, was found to display worse than expected operative efficiency.

Figure 2.

Individual performance curves for surgeons A–D. The graph illustrates the patient-risk-adjusted operative time of the four surgeons selected to test the control charts, with respect to the expected ‘benchmark’ performance curve.

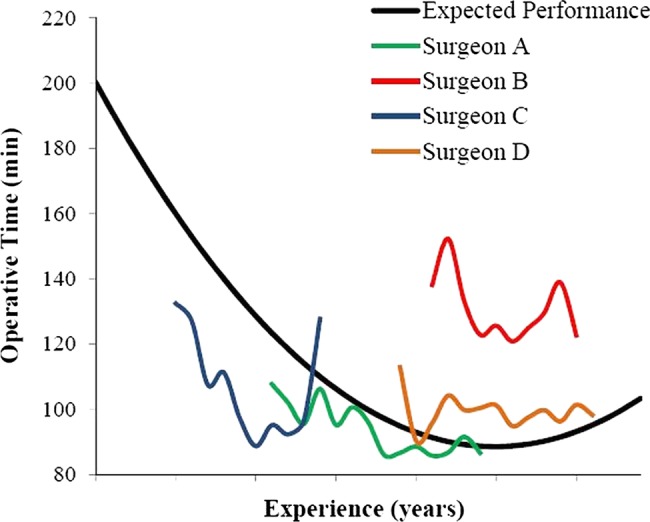

Control charts adjusted only for patient risk depicted surgeon A as improving. However, after adjusting for surgical experience, surgeon A's operative efficiency appeared to worsen relative to the population mean (figure 3). Similarly, surgeon B was found to be within control limits for most of his operations when considering patient-risk adjustment only; however, surgical experience adjustment showed all but one of his data points to lie outside the upper control limit, indicating consistently slower operative efficiency. Experience adjustment transposed surgeon C's performance curve from variable about the population mean to clearly ‘high’ operative efficiency, and inverted the interpretation of surgeon D's operative efficiency from ‘high’ to ‘poor’. The agreement between the patient-risk-adjusted and fully adjusted control charts in detecting operative time variations over surgeons’ career was very low (table 3, κ=0.29 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.47), indicating the significant effect of adjusting operative time for surgical experience.

Figure 3.

Patient-risk-adjusted versus fully adjusted control charts for individual surgeons. For each surgeon a patient-risk-adjusted chart, and fully adjusted (patient-risk-adjusted and surgeon-experience adjusted) chart is displayed. The horizontal axes indicate the experience of the surgeon in years and the blue curve his/her adjusted performance over time. The central black dotted line represents the expected operative time over the course of surgeon's career. The upper red and lower green lines illustrate poor and high performance limits, set at two SDs (dotted warning limits) and three SDs (continuous control limits) around the central line. Poor and high performers are defined as those breaching the upper and lower limits, respectively. Average performers are those with operative time around the central line, without crossing the limits.

Table 3.

Agreement between patient-risk-adjusted and fully adjusted charts in detecting indicator variations

| Fully adjusted chart* |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <LCL | LCL-LWL | LWL-UWL | UWL-UCL | >UCL | ||

| Patient-risk-adjusted chart* | ||||||

| <LCL | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| LCL-LWL | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| LWL-UWL | 7 | 0 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 25 |

| UWL-UCL | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| >UCL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 9 | 2 | 19 | 6 | 11 | 47 |

*Each unit in the table represents the position of a data point on a control chart, according to five ordinal levels based on Warning Limits (2SD) and Control Limits (3SD), as follows: <LCL (below the lower control limit), LCL-LWL (between the lower control and warning limits), LWL-UWL (between the lower and upper warning limits), UWL-UCL (between the upper warning and control limits), >UCL (above the upper control limit).

Adjustment for surgeon's experience, in addition to patient risk, significantly altered the interpretation of operative efficiency, and enhanced the accuracy of assessing a surgeon's improvement or diminishment in efficiency over time.

Discussion

Our study presents a novel methodology for the adjustment and monitoring of surgical metrics, specifically operative efficiency. Surgery is a technical specialty, improving with volume and experience. Consideration of surgeon-specific factors may seem intuitive, but remains poorly investigated. Our findings quantitatively demonstrated that such adjustment significantly altered the interpretation of operative efficiency monitoring—at times resulting in an inversion of perceived trends in efficiency relative to consideration of patient-adjustment alone. Although we investigated the operative time, this methodology can be applied to any surgical outcome.

Fully adjusted control charts were shown to offer an accurate and perceptive means of interpreting trends in a surgeon's efficiency, identifying outlying or anomalous units and providing early warning of divergence from the cohort mean. We believe such factors may prove particularly advantageous in the context of surgeon monitoring and performance tracking.

Limitations

These implications must be considered in the context of this study's limitations. First, this investigation was performed at a single academic medical centre, retrospectively, which may limit the representativeness of our sample. It should be noted, however, that the retrospective nature of our investigation removed any Hawthorne bias with regard to performance, and therefore may provide a truer depiction of procedural dynamics than could have been ascertained through prospective methods. Importantly, our database covered a substantial time period and it is possible that operative technique and technology may have changed during this course of time. Second, our focus on operative time did not implicitly incorporate considerations related to patient outcomes. Studies, however, have indicated that faster completion of the TKR procedure is associated with better outcomes.29 Indeed, in a variety of works, within surgery and outside, time of task completion has been used as a robust indicator of learning and outcome.17 29–33 Furthermore, longer operative time and increased use of the operating theatre, as discussed below, expose patients to greater risks of surgical site infection, while also entailing larger financial costs and reduced efficiency, that amid rising costs in healthcare, are of clear importance. Third, our investigation utilised years of training as a proxy for surgical experience, rather than the number of cases performed. This limitation is a reflection of the fact that a number of surgeons included in the dataset had been in clinical practice prior to the implementation of our surgical tracking application. Years of training, however, has been utilised as an acceptable substitute for surgical experience in previously published studies.15–17 Finally, although we adjusted control charts for patient characteristics and surgeon individual experience, there may be other factors, such as non-technical skills, teamwork and resident involvement which need to be accounted for to enable a better interpretation of performance.

Policy implications

Monitoring the operative time with the aim of improving operative efficiency has strong financial implications. Theatres, excluding day surgery, have been shown to account for approximately 6% of National Health Service (NHS) Trust budgets, equating to running-costs per theatre per year of £1.5 million.34 35 In the USA, the cost of an operating theatre has been estimated at approximately US$130/min.36 Strategies that can improve operative efficiency and reduce operative costs are therefore of importance.

The impact of surgeon-specific adjustment itself also has implications within and outside the sphere of individual performance tracking. In the context of training, it is arguably inequitable to compare the performance of less and more experienced trainees; indeed, it would be inappropriate to expect a surgeon who has just started his/her training to perform similar to a surgeon who is about to complete their training, rather trainees must be compared with cohorts of the same level of experience. Thus, use of surgeon-specific, experience-adjusted charts will permit the performance of young trainees to be accurately and equitably monitored relative to a relevant benchmark, removing the bias. This could give rise to appraisals based on performance rather than career chronology or volume of cases alone, potentially ensuring progression only on acquisition of sufficient expertise. The tools outlined in this study could furthermore be used to establish minimal competency requirements for operators and permit important contributors to training to be quantitatively identified. In the context of experienced surgeons, fully adjusted control charts provide a sensitive and timely means of identifying deviations from expected benchmarks, permitting a prompt investigation or intervention to improve the respective surgeon's performance. A recent work has also shown that performance may decline as surgeons approach seniority37; patient-adjusted and surgeon-adjusted control charts have the capacity to identify this deterioration and supplement the implementation of continuing education programmes. In the broader context of outcomes research, any studies investigating the impact of an intervention on performance could gain interpretational benefit from surgeon-factor adjustment. Where groups of surgeons or departments are being compared, it is intuitive that adjustment for the respective experiences, or ‘surgeon-mix’ of these groups is adjusted for, in parallel with patient-mix adjustment, to improve the transparency of results.

We present this research as a proof-of-concept that (1) patient-adjusted and surgeon-adjusted control charts can be utilised to inform ongoing professional development and feedback for individual surgeons and (2) surgeon-specific adjustment is necessary for correct assessment of operative efficiency and performance outcomes; failure to do so exposes metrics to statistically significant misinterpretation. We believe this should be considered in developments regarding surgical monitoring, to permit equitable and accurate performance assessment, addressing concerns of patients, surgeons and policymakers alike.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AD, DO, JW, MJC, MM and SRL participated in study concept and design; MJC and MM participated in data collection; and AD and SRL participated in analysis; AD, MJC and MM participated in the manuscript preparation and all authors participated in revision.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Brigham and Women's Hospital institutional review board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Further information on data used in the study is available on request.

References

- 1.Godlee F. Measure your team's performance, and publish the results [Editor's Choice]. BMJ 2012;345:e4590 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis K, Schoen C, Guterman S, et al. Slowing the growth of U.S. health care expenditures: what are the options? New York: The Commonwealth Fund, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System Why not the best? Results from a national scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance. New York: The Commonwealth Fund, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimick JB, Weeks WB, Karia RJ, et al. Who pays for poor surgical quality? Building a business case for quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202:933–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duclos A, Carty MJ. Value of health care delivery. JAMA 2011;306:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavare A. Where are we with transparency over performance of doctors and institutions? BMJ 2012;345:e4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray S, Simpson I. Professional societies can lead the way on transparency but will need support. BMJ 2012;345:e5075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill M.. NHS medical director wants surgeon league tables. BBC News [online]. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-20584897 (accessed 4 Mar 2013)

- 9.Holzhey DM, Jacobs S, Walther T, et al. Cumulative sum failure analysis for eight surgeons performing minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134:663–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusamura S, Baratti D, Deraco M. Multidimensional analysis of the learning curve for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in peritoneal surface malignancies. Ann Surg 2012;255:348–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tekkis PP, McCulloch P, Steger AC, et al. Mortality control charts for comparing performance of surgical units: validation study using hospital mortality data. BMJ 2003;326:786–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duclos A, Voirin N, Touzet S, et al. Crude versus case-mix-adjusted control charts for safety monitoring in thyroid surgery. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook JA, Ramsay CR, Fayers P. Statistical evaluation of learning curve effects in surgical trials. Clin Trials 2004;1:421–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wouters MW, Wijnhoven BP, Karim-Kos HE, et al. High-volume versus low-volume for esophageal resections for cancer: the essential role of case-mix adjustments based on clinical data. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:80–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carty MJ, Chan R, Huckman R, et al. A detailed analysis of the reduction mammaplasty learning curve: a statistical process model for approaching surgical performance improvement. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124:706–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu R, Carty MJ, Orgill DP, et al. The teaming curve: a longitudinal study of the influence of surgical team familiarity on operative time. Ann Surg 2013;258:953–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbardissi AW, Duclos A, Rawn JD, et al. Cumulative team experience matters more than individual surgeon experience in cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012; 145:328–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bewick DM. Controlling variation in health care: a consultation from Walter Shewhart. Med Care 1991;29:1212–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tennant R, Mohammed MA, Coleman JJ, et al. Monitoring patients using control charts: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:187–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thor J, Lundberg J, Ask J, et al. Application of statistical process control in healthcare improvement: systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:387–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicolay CR, Purkayastha S, Greenhalgh A, et al. Systematic review of the application of quality improvement methodologies from the manufacturing industry to surgical healthcare. Br J Surg 2012;99:324–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The elements of statistical learning. New York: Springer, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsay CR, Grant AM, Wallace SA, et al. Statistical assessment of the learning curves of health technologies. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery DC. Statistical quality control: a modern introduction. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:458–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duclos A, Voirin N. The p-control chart: a tool for care improvement. Int J Qual Health Care 2010;22:402–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968; 70:213–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J, et al. Prolonged operative time correlates with increased infection rate after total knee arthroplasty. HSS J 2006;2:70–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pisano GP, Bohmer MJ, Edmondson AC. Organizational differences in rates of learning: evidence from the adoption of minimally invasive cardiac surgery. Manage Sci 2001;47:752–68 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edmondson AC, Winslow AB, Bohmer RMJ, et al. Learning how and learning what: effects of tacit and codified knowledge on performance improvement following technology adoption. Decis Sci 2003; 34:197–223 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epple D, Argote L, Devadas R. Organizational learning curves: a method for investigating intra-plant transfer of knowledge acquired through learning by doing. Organ Sci 1991;2:58–70 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Argote L, Epple D. Learning curves in manufacturing. Science 1990;247:920–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Finance/Costs/Detailed-Tables/Theatres.asp (accessed 30 Aug 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 35.West Hertfordshire Hiospitals NHS Trust. http://www.westhertshospitals.nhs.uk/foi_publication_scheme/disclosure_log/2010/december/documents/170%20-%20140111.pdf (accessed 30 Aug 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shippert RD. A study of time-dependent operating room fees and how to save $100,000 by using time-saving products. Am J Cosmet Surg 2005;22:25–34 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duclos A, Peix JL, Colin C, et al. CATHY Study Group Influence of experience on performance of individual surgeons in thyroid surgery: prospective cross sectional multicentre study. BMJ 2012;344:d8041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.