Abstract

Objective

To investigate trends in time to invasive examination and treatment for patient with first time diagnosis of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina during the period from 2001 to 2009 in Denmark.

Design

From 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2009 all first time hospitalisations with NSTEMI and unstable angina were identified in the National Patient Registry (n=65 909). Time from admission to initiation of coronary angiography (CAG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) was calculated. We described the development in invasive examination and treatment probability (CAG, PCI and CABG at 3, 7, 10, 30 and 60 days) for the years 2001–2009, taking the competing risk of death into account using Aalen–Johansen estimators and a Fine-Gray model.

Setting

Nationwide Danish cohort.

Results

The proportion of patients receiving a CAG and PCI increased substantially over time while the proportion receiving a CABG decreased for both NSTEMI and unstable angina. For both NSTEMI and unstable angina, a significant increase in invasive examination and treatment probability at 3 days for CAG and PCI were seen especially from 2007 through to 2009. For NSTEMI, the CAG examination probability at 3 days leaped from 20% in 2007 to 32% in 2008 and 39% in 2009, and for PCI the same was true with a leap in treatment probability from 19% to 28% from 2008 to 2009.

Conclusions

In Denmark the use of CAG and PCI in treatment of NSTEMI and unstable angina has increased from 2001 to 2009, while the use of CABG has decreased. During the same period, there was a marked increase in invasive examination and treatment probability at 3 days, that is, more patients were treated faster which is in line with the political aim of reducing time to treatment.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large unselected patient population n=65 909.

Detailed register-based data.

Use of statistical methods that account for competing risks.

Information on extension and severity of the disease.

No information on biomarkers to validate register-based data.

No information on why patients died without treatment.

Introduction

Treatment of acute coronary heart disease has advanced substantially during the latest decades, and improved clinical outcome has been seen.1 A recent register-based Danish cohort study by Schmidt et al2 found that short-term mortality after first time hospitalisation with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was nearly halved from 1984 to 2008. It has been suggested that part of this decline can be attributed to improved treatment including introduction of thrombolysis, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and improved medical prevention after diagnosis.3 Coronary angiography (CAG) is recommended as part of the diagnostic process for all patients with AMI with PCI as the primary intervention.4 Since the mid-1990s, there has been a strong political focus on time to treatment in order to reduce case fatality.5 For coronary heart disease, this focus in Denmark has among other initiatives led to the development of fixed treatment protocols for patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina. These protocols were implemented during 2009. The protocol stipulates that the maximum time from admission with NSTEMI to invasive examination (CAG) should be less than 3 calendar-days (72 h) and time to appropriate invasive treatment less than 3 calendar-days for PCI and 7 calendar-days for CABG.6 These protocols are based on the shared European guidelines.4 7

The purpose of this study was to investigate a potential explanation of the significant improvement in prognosis by describing time to invasive examination and treatment for patients with first-time diagnosis of NSTEMI or unstable angina during the period from 2001 to 2009 in Denmark using a nationwide cohort design and taking into account vessel disease severity as well as using appropriate methods of analysis that account for the competing risk of death. This study is the first nationwide cohort study to describe time waited for CAG, PCI and CABG over a decade where large changes in treatment of NSTEMI and unstable angina were introduced including the introduction of fixed treatment protocols.

Method

The Danish healthcare system provides universal coverage for all citizens. Since 1995, all contacts with the healthcare system including emergency, ambulatory and inpatient have been registered in the National Patient Registry (NPR) with information about time and date of admission and discharge along with information about diagnosis as well as type and date of potential invasive treatment or examination.8 Furthermore, there are several registers and clinical quality databases with patient-specific information9 that can be linked with the data from the NPR through the use of the unique 10-digit person identifier. The registers used for this study are the NPR, the Danish Heart Registry, which registers information regarding patients undergoing invasive cardiac procedure10 and the Medical Cause of Death Registry, which contains information on time and cause of death.11

Study population

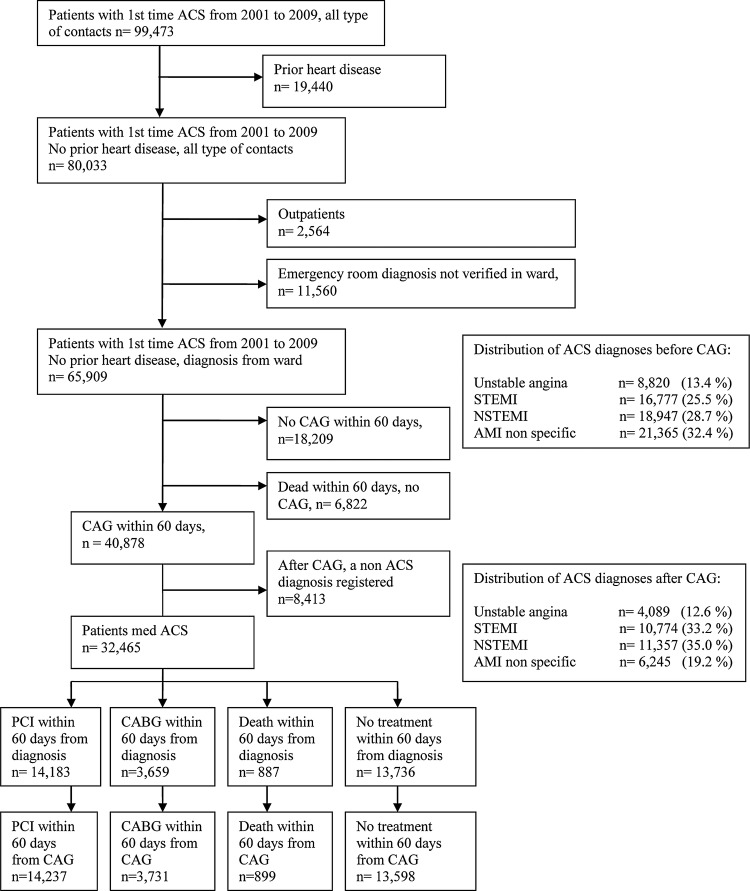

From 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2009 all first time hospitalisations of acute coronary heart syndrome (ACS) were identified in the NPR (n=99 473) by the following International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10 codes (I20.0 Unstable angina pectoris, I21.0–I21.3 ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), 121.4 NSTEMI and I21.9 AMI—unspecified) using discharge diagnoses (see figure 1). Patients with prior heart disease (ICD10: I20–I25) were excluded using information from the NPR going back to 1995 (n=19 440) leaving 80 033 patients. A previous study by Joensen et al12 found that the ACS diagnosis registered in the NPR should be used with caution especially the unstable angina diagnosis. Joensen et al recommend restricting the analysis to patients discharged from wards when another validation is not possible. We therefore excluded outpatients (n=2564) and patients with an NSTEMI or unstable angina diagnosis from an emergency room that was not verified in the subsequent admission (n=11 560), still allowing for a shift from NSTEMI to unstable angina or vice versa. Consequently, the final population consisted of 65 909 patients. Diagnosis can change after the result of CAG; therefore, we used the diagnosis registered after the CAG in the analysis of time to PCI and CABG. For this reason the number of patients in the different subdiagnosis groups varies between analyses of CAG, PCI and CABG (see figure 1 for distribution of patients with ACS in subdiagnosis groups at initial examination and after CAG). Patients with STEMI and unspecified myocardial infarction (MI) are only included in the initial descriptive analysis of the patient population.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient population.

Variables

Time to examination or treatment (from admission to CAG, PCI and CABG)

Time (measured in hours) from admission to initiation of CAG, PCI or CABG was calculated using information from the NPR (the specific SKS codes can be seen in online supplementary appendix 1). Only treatment and examination within the first 60 days after initial symptom presentation were included. Further information regarding this variable can be found in the online supplementary appendix 2.

Severity and extent of disease

Severity and the extent of disease will influence the perceived urgency of treatment. Information on the number of occluded vessels and left main coronary artery (LMCA) involvement was available from the Danish Heart Register (DHR) in 82.1% and 84.7% of the cases that received a CAG, respectively. We allowed for a slip of ±2 days between NPR CAG date and DHR CAG date when identifying CAG information.

Other covariates include sex, age and year of diagnosis.

Statistical methods

In the descriptive analysis, the number of patients receiving CAG, PCI or CABG was reported along with the number of patients receiving the respective examination or treatment within 3 days for CAG and PCI and 7 days from CAG for CABG for each diagnosis and for each of the covariates: age, sex, number of occluded vessels and LMCA involvement. When investigating time to treatment for a specific disease, it is important to account for the competing risk of death in order to account for the time waited by patients who die before they are treated.13 Reporting a median time to treatment is not relevant as it will only describe the time waited by patients who manage to be treated. Furthermore, if we wish to model cumulated probability of treatment (not intensities) and applied standard methods (eg, Cox regression method or Kaplan–Meier plots), then we would regard death without treatment as independent censoring and would only be able to make inference for a hypothetical population where patients do not die without being treated.13 The problem of competing risks is especially important for a potentially fatal disease like ACS where some subdiagnosis has a relative high mortality rate.14 15 Furthermore, as first-line invasive treatments are mutually exclusive (patients receive either PCI or CABG), we need to account for the competing risk of receiving the other treatment, respectively. To account for this competing risk problem, we used Aalen-Johansen plots where we described the development in invasive examination (CAG) and treatment probability (PCI and CABG) for the years 2001–2009. These plots account for the competing risks of death and treatment (PCI or CABG, respectively) by showing the estimated percentage of the original population, which at a given time has received the examination (CAG) and treatment (PCI or CABG). The plot has no distributional assumptions.13 From these plots we derived probability at 1, 3, 7 (only for CABG), 10, 30 and 60 days after diagnosis. These probabilities are presented in graphs in order to show the development from 2001 to 2009.

To test whether the effects seen in the plots were statistically significant, we used the Fine-Gray model, a regression model that accounts for competing risks and adjusts for covariates.13 In this model we find the effect of the calendar years when controlling for covariates (age, sex, LMCA involvement and number of occluded vessels).

When analysing the impact of the fixed treatment protocols implemented during 2009, a proper evaluation with a control group was not feasible due to lack of an appropriate comparison group. Consequently we applied a second-best solution where we looked at whether the change in times to examination or treatment in the year 2009 differed from the time trend observed in the time period from 2001 to 2008 extrapolated to 2009. The use of this method was inspired by the methods used by Lee et al16 when evaluating the effects of Pay for Performance in the UK. We tested this in the Fine-Gray model and report the test statistics as z. Year 2001 is the reference when year is included categorically. In all analyses, a 5% significance level was used.

Data were analysed with SAS V.9.3, STATA V.12.1 and by using the macro COMPRISK to draw Aalen-Johansen plot provided open access by the MAYO Institute.

Results

Of the 65 909 patients identified, 28.7% were admitted with NSTEMI, 13.4% with unstable angina, 25.5% with STEMI and 32.4% with non-specified MI. A total of 8412 patients were after the CAG registered with a non-ACS diagnosis and subsequently excluded from further analysis of PCI and CABG (see online supplementary appendix 3 where the diagnoses that account for 80% of these patients are listed). After CAG, the distribution of diagnosis was as follows: 35% of patients were admitted with NSTEMI, 12.6% with unstable angina, 33.2 with STEMI and 19.2 with non-specific MI.

Table 1 show that from 2001 to 2009, the proportion of patients with NSTEMI receiving a CAG and PCI increased substantially, while the proportion receiving a CABG decreased. During the same period, the fraction of patients examined with a CAG who received this within 3 days increased from 18.2% to 55.7%. For PCI a similar development was seen with 52% treated within 3 days in 2009 compared with 27.5% treated in 2001. For CABG, within 7 days the percentage slightly declined over the time period with some fluctuations.

Table 1.

CAG, PCI and CABG treatment rates and number of patients treated within 3/7 days distributed according to covariates for patients with first time NSTEMI

| NSTEMI | Diagnosis at initial examination |

Diagnosis registered after CAG |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAG within 60 days |

PCI within 60 days (grouped according to after CAG diagnosis) |

CABG within 60 days from CAG |

|||||||

| Examination rate (%) | n | Per cent in 3 days* | Treatment rate (%) | n | Per cent in 3 days* | Treatment rate (%) | n | Per cent in 7 days* | |

| Overall | |||||||||

| 18.947 | 63.3 | 11 997 | 31.8 | 52.7 | 5984 | 30.7 | 16.2 | 1836 | 26.3 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||||||

| 2001 | 49.8 | 823 | 18.2 | 48.4 | 255 | 27.5 | 23.0 | 121 | 29.5 |

| 2002 | 54.9 | 1177 | 19.9 | 49.6 | 465 | 24.8 | 22.8 | 214 | 23.7 |

| 2003 | 58.7 | 1355 | 26.2 | 51.4 | 597 | 21.2 | 19.5 | 226 | 38.5 |

| 2004 | 61.3 | 1422 | 23.2 | 54.3 | 673 | 24.2 | 17.8 | 221 | 35.5 |

| 2005 | 67.7 | 1480 | 26.6 | 56.7 | 771 | 23.7 | 16.2 | 220 | 25.7 |

| 2006 | 68.0 | 1401 | 28.9 | 55.1 | 792 | 24.6 | 13.1 | 188 | 23.3 |

| 2007 | 66.9 | 1438 | 30.7 | 49.5 | 728 | 27.4 | 16.5 | 243 | 15.3 |

| 2008 | 70.5 | 1533 | 46.2 | 50.3 | 817 | 38.9 | 13.2 | 214 | 24.7 |

| 2009 | 70.0 | 1368 | 55.7 | 55.3 | 886 | 52.0 | 11.8 | 189 | 23.0 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Men | 70.8 | 8072 | 32.3 | 56.3 | 4247 | 30.8 | 18.8 | 1424 | 25.7 |

| Women | 52.1 | 3791 | 29.4 | 47.0 | 1615 | 26.9 | 11.2 | 386 | 28.0 |

| Age | |||||||||

| 30 or younger | 86.7 | 26 | 37.5 | 15.0 | 3 | 66.7 | – | – | – |

| 30–39 | 91.5 | 225 | 44.3 | 53.1 | 111 | 42.9 | 2.3 | 5 | 60.0 |

| 40–49 | 91.4 | 1093 | 40.6 | 59.2 | 599 | 42.2 | 7.0 | 72 | 33.8 |

| 50–59 | 89.4 | 2521 | 33.2 | 61.0 | 1459 | 29.8 | 12.5 | 302 | 28.3 |

| 60–69 | 84.0 | 3543 | 29.8 | 52.5 | 1703 | 28.3 | 20.8 | 675 | 25.6 |

| 70–79 | 66.1 | 3337 | 27.6 | 47.9 | 1472 | 25.9 | 21.7 | 665 | 23.7 |

| 80 or older | 21.8 | 1118 | 31.2 | 49.7 | 515 | 27.5 | 8.7 | 91 | 33.3 |

| LMCA involvement | |||||||||

| Yes | 18.7 | 39 | 33.3 | 65.6 | 137 | 50.4 | |||

| No | 54.6 | 4885 | 32.1 | 14.3 | 1276 | 24.9 | |||

| Number of occluded vessels | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.9 | 22 | 31.8 | 0.3 | 4 | 50.0 | |||

| 1 | 78.5 | 2592 | 36.2 | 1.5 | 49 | 36.7 | |||

| 2 | 71.7 | 1393 | 32.0 | 12.7 | 246 | 23.4 | |||

| 3 | 30.0 | 630 | 30.1 | 49.3 | 1034 | 29.6 | |||

*National guidelines recommend CAG and PCI within 3 days of diagnosis and CABG within 7 days of CAG.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAG, coronary angiography; LMCA, left main coronary artery; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

For unstable angina, the activity rate increased for CAG, but not for PCI in the period from 2001 to 2009 (table 2); however, for both CAG and PCI the rates of patients who received these procedures within 3 days doubled in this time period. For CABG the treatment rate was more than halved.

Table 2.

CAG, PCI and CABG treatment rates and number of patients treated within 3/7 days distributed according to covariates for patients with first time unstable angina

| Unstable angina | Diagnosis at initial examination |

Diagnosis registered after CAG |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAG within 60 days |

PCI within 60 days (grouped according to after CAG diagnosis) |

CABG within 60 days from CAG |

|||||||

| Examination rate (%) | n | Per cent in 3 days* | Treatment rate (%) | n | Per cent in 3 days* | Treatment rate (%) | n | Per cent in 7 days* | |

| Overall | |||||||||

| 8820 | 71.4 | 6300 | 44.2 | 49.7 | 2031 | 38.9 | 18.0 | 735 | 43.7 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||||||

| 2001 | 59.9 | 631 | 30.2 | 51.3 | 224 | 24.9 | 26.8 | 117 | 47.2 |

| 2002 | 61.0 | 649 | 32.0 | 47.6 | 200 | 31.2 | 28.8 | 121 | 44.5 |

| 2003 | 64.5 | 633 | 37.1 | 49.5 | 206 | 33.5 | 22.8 | 95 | 55.3 |

| 2004 | 72.3 | 663 | 33.1 | 43.4 | 170 | 23.3 | 20.4 | 80 | 53.4 |

| 2005 | 74.1 | 705 | 43.1 | 51.2 | 229 | 38.1 | 14.5 | 65 | 36.7 |

| 2006 | 74.3 | 753 | 44.6 | 52.3 | 228 | 39.9 | 14.0 | 61 | 42.1 |

| 2007 | 78.3 | 720 | 51.9 | 49.2 | 214 | 43.0 | 15.9 | 69 | 30.0 |

| 2008 | 82.1 | 823 | 55.5 | 50.4 | 317 | 52.6 | 11.6 | 73 | 42.0 |

| 2009 | 79.0 | 723 | 62.0 | 50.9 | 243 | 51.1 | 11.3 | 54 | 29.2 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Men | 74.9 | 3719 | 44.6 | 51.6 | 1318 | 39.5 | 21.4 | 549 | 44.1 |

| Women | 66.7 | 2305 | 37.7 | 48.2 | 658 | 33.4 | 12.0 | 166 | 41.7 |

| Age | |||||||||

| 30 or younger | 64.3 | 18 | 61.1 | – | – | – | 14.3 | 1 | 0 |

| 30–39 | 71.4 | 177 | 43.0 | 39.1 | 34 | 52.9 | 4.5 | 4 | 25.0 |

| 40–49 | 75.6 | 684 | 43.7 | 49.5 | 207 | 45.8 | 7.3 | 31 | 50.0 |

| 50–59 | 80.4 | 1562 | 40.0 | 54.0 | 534 | 39.9 | 13.8 | 137 | 37.0 |

| 60–69 | 78.3 | 1841 | 42.7 | 50.3 | 609 | 36.1 | 21.8 | 265 | 46.7 |

| 70–79 | 70.7 | 1350 | 40.8 | 46.9 | 429 | 32.3 | 26.7 | 244 | 42.7 |

| 80 or older | 37.8 | 392 | 45.8 | 55.3 | 163 | 34.7 | 11.0 | 33 | 50.0 |

| LMCA involvement | |||||||||

| Yes | 14.8 | 21 | 47.6 | 75.4 | 107 | 60.0 | |||

| No | 52.6 | 1684 | 39.7 | 15.5 | 496 | 39.8 | |||

| Number of occluded vessels | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.9 | 11 | 50.0 | 0.5 | 3 | 0 | |||

| 1 | 79.1 | 1010 | 44.1 | 2.3 | 30 | 40.0 | |||

| 2 | 67.1 | 451 | 36.7 | 19.6 | 132 | 42.3 | |||

| 3 | 26.5 | 186 | 31.8 | 58.3 | 409 | 43.8 | |||

*National guidelines recommend CAG and PCI within 3 days of diagnosis and CABG within 7 days of CAG.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAG, coronary angiography; LMCA, left main coronary artery; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

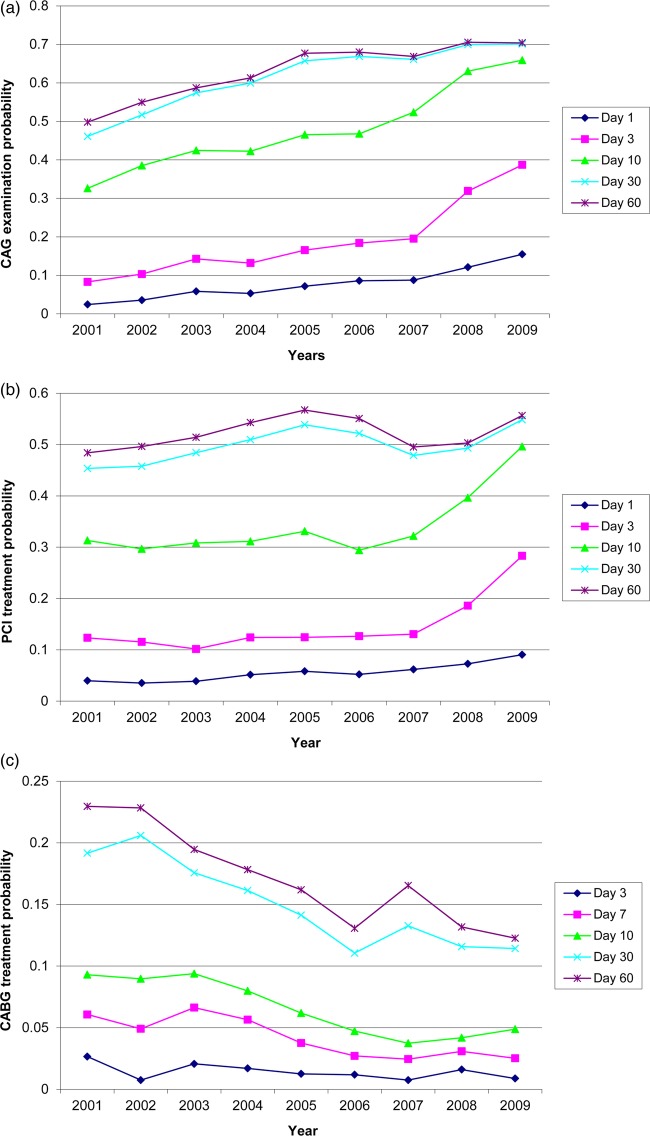

Figure 2A shows the development in the probability of invasive examination using CAG from 2001 to 2009 for NSTEMI accounting for the competing risk of death. The figure shows a significant increase in the use of CAG in the period from 2001 to 2005 with an increase in probability from 49.8% for CAG at 60 days in 2001 to 70.4% in 2005 (tested using the Fine–Gray model, see results in online supplementary appendix 4). From 2005 onwards only a slight increase in probability of CAG at 60 days was seen. The figure also shows a steady increase in the probability of CAG within 3 days from 2001 to 2007 followed by a leap from 19.5% in 2007 to 31.9% in 2008 and a further increase to 38.7% in 2009. The fixed treatment protocol seemed to have a significant effect on the probability of receiving a CAG within 3 days (z=4.16; p<0.001). For PCI (figure 2B), there was only a slight increase in the probability of treatment with PCI at 60 days from 2001 to 2009. Further, the probability of PCI treatment within 3 days increased markedly from 2007 to 2008 and again from 2008 to 2009. The effect of the implementation of the fixed treatment protocols also revealed a significant effect for PCI (z=7.44; p<0.001). For CABG the development in the treatment probability was somewhat different with a significant drop in probability of receiving this type of invasive treatment over the period 2001–2006 with subsequent stagnation (figure 2C). The probability of CABG within 7 days of CAG decreased significantly over the period and there seemed to be no effect of the fixed treatment protocols (z=0.50; p=0.62).

Figure 2.

Development in coronary angiography (CAG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) treatment probability from 2001 to 2009 for patients with Non ST elevation myocardial infarction at day 1, 3, 7 (CABG only), 10, 30 and 60.

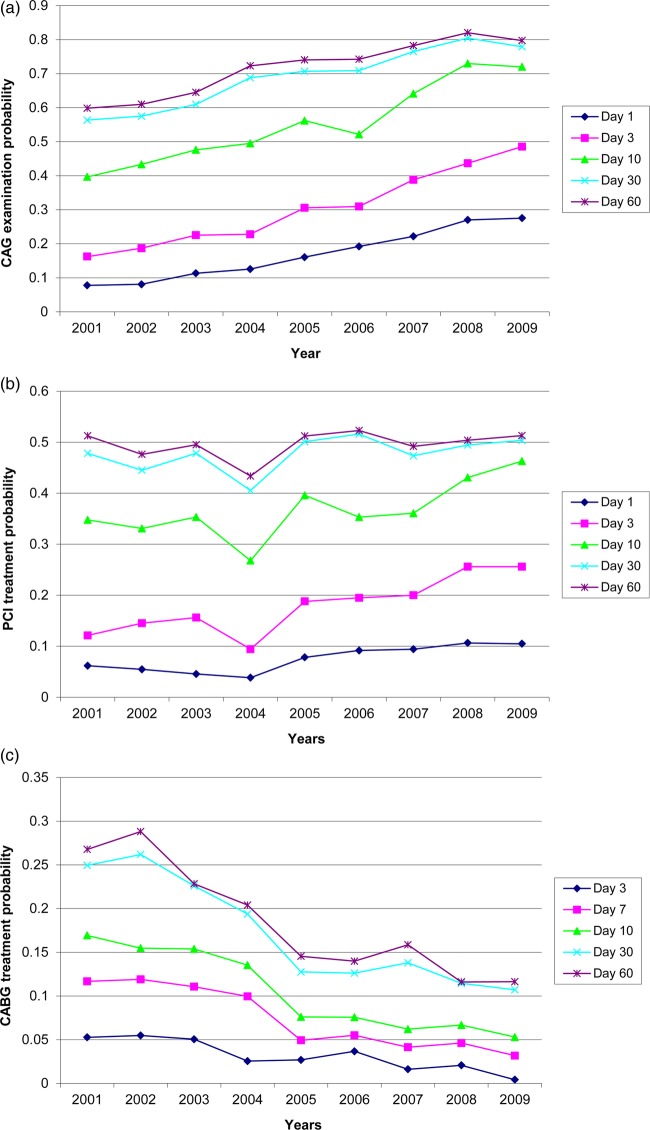

Figure 3 shows similar graphs for patients with unstable angina. In general, the development was very similar to that of patients with NSTEMI, but with the increase in the invasive examination and treatment rate later in the observation period (from 2004 to 2008). The probability of receiving CAG within 3 days increased threefold from 2001 to 2009 with an almost constant increase (figure 3A). We saw no effect of the fixed treatment protocols on timing of CAG (z=−0.50; p=0.62). The PCI treatment rate at 60 days was somewhat stable in the time period with a small drop in 2004, while the probability of treatment within 3 days increased almost constantly from 2001 to 2009. There was no effect of the fixed treatment protocols (z=−0.32; p=0.75; figure 3B). For CABG the treatment probability at 60 days decreased in the time period as well as the treatment probability at 7 days (figure 3C). There was no significant effect of the fixed treatment protocols. For both NSTEMI and unstable angina, there was no significant development in death before treatment over time, that is, a competing risk (analysis not shown).

Figure 3.

Development in coronary angiography (CAG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) treatment probability from 2001 to 2009 for patients with unstable angina at day 1, 3, 7 (CABG only), 10, 30 and 60.

When including age, sex, number of occluded vessels and LMCA involvement (last 2 only for PCI and CABG), we found that for NSTEMI the development in CAG examination probability at 3 days and 60 days was the same as seen in the unadjusted analyses, and the effect of the fixed treatment protocols remained significant. For PCI, the same pattern was observed; however, when adjusting for the number of occluded vessels, the linear effect of year became insignificant, but the effect of the fixed treatment protocols remained. For CABG, the picture did not change after the adjustment except that the decrease in treatment probability seen at 60 days was not as noticeable as in the unadjusted analysis. Performing the same adjustments did not change the conclusions for unstable angina either (see all results from the Fine-Gray model in online supplementary appendix 5).

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study, we found a significant increase in the proportions of patients with NSTEMI and unstable angina receiving a CAG and PCI in Denmark between 2001 and 2009, while the proportion receiving CABG decreased. In the analysis accounting for competing risks, there was an increase in the probability of examination and treatment within 3 days for CAG and PCI after 2001, and there seemed to be a significant effect of the introduction of a fixed treatment protocol with recommended maximum time from diagnosis to invasive examination and treatment for NSTEMI, but not for unstable angina.

Our results are in agreement with studies from the USA, which showed an increase in the use of CAG and PCI over the past two decades, and a decrease in CABG.1 17 18 The study also contributes to the interpretation of the findings from a recent Danish study,2 which showed a significant reduction in 30-day and 1-year mortality risk after first time hospitalisation for MI between 1999–2003 and 2004–2008. Part of this reduction could be due to a decrease in time to treatment. When comparing with this study, one should keep in mind that we did not include patients with STEMI who are included in Schmidt et al’s study and that these patients have a succinct treatment path with the need for more urgent treatment. There seems to be no other nationwide studies on trends in time from diagnosis to invasive treatment; however, in 2009 Bradley et al19 reported a decrease in door-to-balloon time for patients with STEMI after enrolment in a national quality campaign with the aim to reduce the door-to-balloon time to less than 90 min for this group.

We did find a significant decline in time for CAG and PCI corresponding to the implementation of the fixed treatment protocol for NSTEMI. However, for both NSTEMI and unstable angina, we found a steady increase in treatment rate from 2001 onwards and for NSTEMI a steep increase in probability already in 2008. This indicates that focus on improvement on time to invasive examination and treatment is not new. Furthermore, the treatment protocols were first implemented during 2009, but they were already discussed in 2008 and this could have led to early implementation and hence an increase in speed of invasive examination and treatment before the actual implementation. In this time period, there seemed to be a general agreement on the benefits of an invasive strategy versus medical management for patients with NSTEMI.20 21 However, the optimal timing of invasive interventions was not clearly agreed on. Mehta et al published in 2009 their results from the large TIMACS trial which included 3031 patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI. They found a significantly lower risk of death, MI or stroke at 6 months for high-risk patients when comparing an early (less than 24 h) with a delayed strategy (more than 36 h). Furthermore, they found no safety issues related to the early strategy.22 This shows the importance of early invasive treatment; however, these results only reflect the difference between very early and early invasive intervention which is a slightly another discussion than ours. In 2010 a meta-analysis was published combining four trials which concluded that early angiography and if relevant treatment for patients with NSTEMI reduces the risk of recurrent ischaemia and shortens hospital stay.23 These results were, however, not reflected in the European Society of Cardiology guidelines until 2011.4 However, the previous guideline from 2007 (ibid, p.27) also stated:“…Accordingly, currently available evidence does not mandate a systematic approach of immediate angiography in NSTE-ACS patients stabilized with a contemporary pharmacological approach. Likewise, routine practice of immediate transfer of stabilized patients admitted in hospitals without onsite catherization facilities is not mandatory, but should be organized within 72 h”.7 We found that the number of patients receiving the recommended invasive examination and treatment within the recommend time frame increased from 2001 to 2009; however, a large group of patients still received no invasive investigation or were treated later than the guideline recommends in 2009. This patient group consists of three possible groups: patients that do not have the disease in question due to lack of validity of data (see later discussion of Strengths and Weaknesses), patients who are too ill to be treated and patients who receive a less than optimal treatment. The basic idea behind the fixed treatment protocol, that is same treatment for patients presenting with the same clinical symptoms irrespective of when or where patients come in contact with the healthcare system should ensure that the latter group is proportionally smaller in 2009 than in 2001. However, there could still be patients who do not receive optimal treatment and unexplained variation between hospitals. Therefore, monitoring by health authorities is of great importance.

Strengths and weaknesses

The primary strength of this study is the large unselected patient population, as it covers all patients admitted with first time ACS during the period from 2001 to 2009 in Denmark. The patients were identified in the NPR; however, this means that we do not have information on biomarkers but solely rely on the correctness on what is registered in the NPR. We excluded outpatients and patients with a diagnosis from an emergency room which was not verified in a ward subsequently; however, especially the unstable angina diagnosis is still problematic. Thus, it has been found that the positive predictive value of unstable angina for patients discharged from a ward only seems to be around 40%.12 Therefore, one reason for the lack of effect of the fixed treatment protocols for this group of patients could be that a substantial part of this group does not have unstable angina. The data in the NPR allowed us to follow patients through the course of diagnosis and treatment path, and we utilised this to change patients’ diagnoses after the CAG in case another diagnosis was registered at this point in time. This was carried out in order to imitate the clinical situation. At CAG 8412 patients had a diagnosis other than ACS. The largest group was 3230 patients with angina no specification. This group of patients could potentially be patients with unstable angina; however; including this group did not change the conclusions (analysis not shown). We had information on the specific hour of admission and used this information to calculate time to treatment. Although the validity of this information can be questioned, we used it in order to calculate the time as precisely as possible. We only included treatment and examination within 60 days as ACS is an acute disease for which treatment, if relevant, should be initiated as soon as possible. We analysed our data by use of statistical methods that accounted for the competing risk of death, which is very important when we estimate trends in time to treatment in a population with a high risk of death. However, we do not know whether patients who died were not treated because the risk of invasive examination and treatment was deemed too high, or because the treatment was not considered relevant. Our analysis showed that the group of patients not receiving CAG was reduced in the period from 2001 to 2009, which was primarily due to an increase in examination of elderly patients (analysis not shown). We also included information on the number of occluded vessels and LMCA involvement as a measure of the extension and severity of the disease in the analysis. This information was only available for 84.7% and 82.1% of the patients, and especially patients from 2001 and 2002 had missing information on this variable. However, we have no reason to believe that this missing data should be non-random and related to time to treatment. Furthermore, we did not use age-standardised data in the trend analyses because the fixed treatment protocols include all patient groups. However, we tested whether there was an effect of the treatment protocols in the Fine-Gray model which adjusted for age, gender, LMCA involvement and number of occluded vessels. The analyses showed that these variables did not change the effect of the treatment protocols. It should also be noticed that we did not include patients who died before arrival to a hospital as these patients are not included in the NPR. It should also be noticed that our study is an observational trend study and we cannot exclude that other organisational or treatment factors than the introduction of the fixed treatment protocol have contributed to the observed reduction in time to examination and treatment. This study only evaluates the immediate effects of the fixed treatment protocols; however, a longer follow-up would also be of interest.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the interpretation of the recent decline in mortality after hospitalisation for MI by showing a contemporary increase in the proportion of patients receiving a CAG and PCI as well as an increase in the probability of patients receiving CAG and PCI within the recommended time. The study also suggest that the introduction of fixed treatment protocols with a recommended maximum time from diagnosis to invasive examination and treatment may have impacted on time to treatment as more patients receive a CAG and PCI within the time limit of 3 days around the time of the introduction of the protocols.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SM, DG-H, EP, A-DOZ and MO contributed to the design of the study. SM carried out statistical analysis with guidance from PKA and MO. SM wrote the initial draft and all authors critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Danish Heart Association (grant number 10-04-R78-A2806-22609), The Health Insurance Foundation (grant number 2011B037), Fabrikant Ejner Willumsens Mindelegat og Aase og Ejner Danielsens Foundation.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This register-based study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (approval number 2010-41-5263). Register-based studies do not need approval by a medical ethics committee in Denmark.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Fox KA, Steg PG, Eagle KA, et al. Decline in rates of death and heart failure in acute coronary syndromes, 1999–2006. JAMA 2007;297:1892–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt M, Jacobsen JB, Lash TL, et al. 25 year trends in first time hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction, subsequent short and long term mortality, and the prognostic impact of sex and comorbidity: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2388–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2999–3054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen KM, Christiansen T, Bech M. The Danish health care system: evolution—not revolution—in a decentralized system. Health Econ 2005;14(Suppl 1):S41–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danish National Board of Health. 2009. Treatment protocols for unstable angina and acute myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation. http://www.sst.dk/Udgivelser/2009/Pakkeforloeb%20for%20ustabil%20angina%20pectoris%20UAP%20og%20akut%20myokardieinfakt%20uden%20st-elevation%20NSTEMI.aspx.

- 7.Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1598–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(Suppl 7):30–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green A. Danish clinical databases: an overview. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(Suppl 7):68–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abildstrom SZ, Madsen M. The Danish Heart Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(Suppl 7):46–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of causes of death. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(Suppl 7):26–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joensen AM, Jensen MK, Overvad K, et al. Predictive values of acute coronary syndrome discharge diagnoses differed in the Danish National Patient Registry. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:188–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de WT, et al. Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:861–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen LO, Thayssen P. [Treatment and prognosis after acute coronary syndrome in an unselected patient population]. Ugeskr Laeger 2007;169:492–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikus KC, Eskola MJ, Virtanen VK, et al. Mortality of patients with acute coronary syndromes still remains high: a follow-up study of 1188 consecutive patients admitted to a university hospital. Ann Med 2007;39:63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JT, Netuveli G, Majeed A, et al. The effects of pay for performance on disparities in stroke, hypertension, and coronary heart disease management: interrupted time series study. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e27236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, et al. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med 2011;124:40–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson ED, Shah BR, Parsons L, et al. Trends in quality of care for patients with acute myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J 2008;156:1045–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, Herrin J, et al. National efforts to improve door-to-balloon time results from the Door-to-Balloon Alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:2423–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ, Rassi AN, et al. Benefit of early invasive therapy in acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of contemporary randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:1319–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox KA, Poole-Wilson PA, Henderson RA, et al. Interventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Randomized intervention trial of unstable angina. Lancet 2002;360:743–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2165–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katritsis DG, Siontis GC, Kastrati A, et al. Optimal timing of coronary angiography and potential intervention in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2011;32:32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.