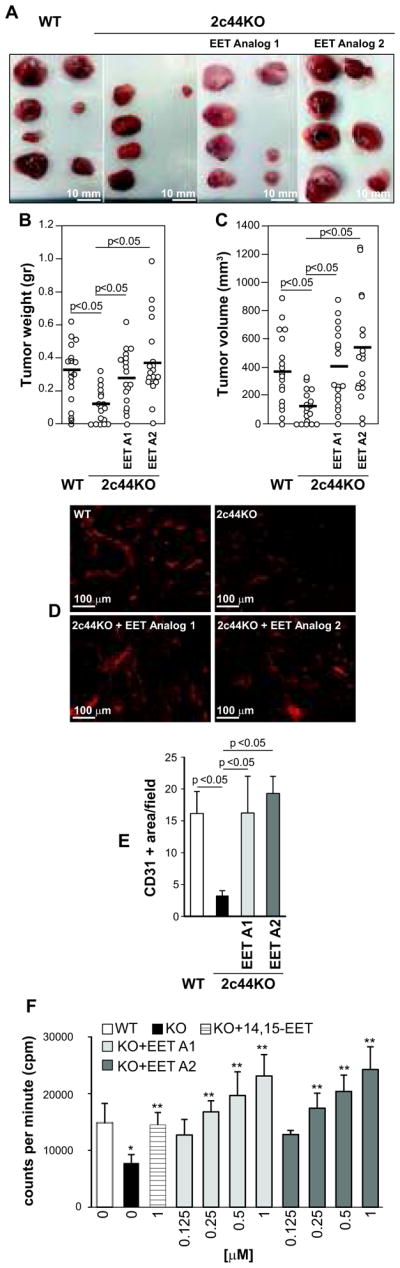

Figure 1. EET analogs promote tumorigenesis.

(A) Images of large T antigen/ras/Myc-transformed mouse fibroblast p60.5 cell-derived tumors grown in the mice indicated. Mice were left untreated or administered the EET analogs 2-(13-(3-pentylureido)tridec-8(Z)-enamido)succinic acid (EET Analog 1) or N-isopropyl-N-(5-((2-pivalamidobenzo[d]thiazol-4-yl)oxy)pentyl)heptanamide (EET Analog 2) for 4 days prior injection with tumor cells. Mice were further treated for 2 weeks and then sacrificed. (B, C) Weight (B) and volume (C) of tumors grown in the mice indicated (n=9). Circles show individual values, while bars show mean values. (D, E) Frozen sections of the tumors grown in the mice indicated were stained with anti-mouse CD31 antibodies and their vascularization was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. The values are means ± S.D. of 10 tumors/group with 2 images/tumor analyzed. (F) Primary lung endothelial cells were cultured with or without 14,15-EET or the EET analogs (EET A1 and EET A2) at the indicated concentrations. Cell proliferation was then evaluated as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means ± S.D. of 3 experiments performed in quadruplicate. p<0.05 between untreated WT vs. Cyp2c44KO (*) or untreated vs. treated Cyp2c44KO (**) cells.