Abstract

SMARCAL1 promotes the repair and restart of damaged replication forks. Either overexpression or silencing SMARCAL1 causes the accumulation of replication-associated DNA damage. SMARCAL1 is heavily phosphorylated. Here we identify multiple phosphorylation sites, including S889, which is phosphorylated even in undamaged cells. S889 is highly conserved through evolution and it regulates SMARCAL1 activity. Specifically, S889 phosphorylation increases the DNA-stimulated ATPase activity of SMARCAL1 and increases its ability to catalyze replication fork regression. A phosphomimetic S889 mutant is also hyperactive when expressed in cells, while a non-phosphorylatable mutant is less active. S889 lies within a C-terminal region of the SMARCAL1 protein. Deletion of the C-terminal region also creates a hyperactive SMARCAL1 protein suggesting that S889 phosphorylation relieves an auto-inhibitory function of this SMARCAL1 domain. Thus, S889 phosphorylation is one mechanism by which SMARCAL1 activity is regulated to ensure the proper level of fork remodeling needed to maintain genome integrity during DNA synthesis.

INTRODUCTION

To ensure complete and accurate duplication of their genomes, cells use multiple DNA repair and signaling mechanisms during DNA replication. These replication stress response mechanisms operate during every S-phase when replication forks stall owing to DNA lesions, insufficient nucleotides, collisions between the replisome and transcriptional apparatus and difficult to replicate sequences. The replication stress response is needed to ensure the completion of DNA synthesis and the maintenance of genome integrity (1,2).

The SNF2 ATPase family member SMARCAL1 (also known as HARP) is a replication stress response enzyme that functions to repair damaged replication forks and restart stalled forks. SMARCAL1 is recruited to replication forks via a direct interaction with the single-stranded DNA binding protein RPA (3–6). SMARCAL1 also binds directly to forked DNA structures, and DNA binding activates its ATPase activity (7–9).

SMARCAL1 uses the energy of ATP hydrolysis to catalyze fork remodeling. Specifically, it can anneal DNA strands and branch migrate DNA junctions (7,8,10). Its branch migration activity allows it to catalyze both regression of a replication fork into a chicken foot structure and reversal of that chicken foot structure back into a normal fork configuration (11). These activities are controlled by its direct interaction with RPA such that it catalyzes fork regression when the replication fork has a single strand gap on the leading strand template and catalyzes fork restoration when the chicken foot has a longer 3' tail (11). The net effect of these activities is a preferential regression of stalled forks generated by leading strand damage and restoration of normal forks with lagging strand gaps. These substrate preferences are shared by the Escherichia coli RecG enzyme (11), and SMARCAL1 may be the functional ortholog of RecG (10,11).

Biallelic loss of function mutation of SMARCAL1 causes the disease Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia (12). This rare disease is characterized by growth defects, immune deficiencies, renal failure and also an increased risk of cancer (13,14). Severely affected patients often die in childhood from renal failure or infection.

Loss of SMARCAL1 function in cells causes the accumulation of collapsed replication forks and hyper-activation of the DNA damage response due to enzymatic action of the MUS81 structure-specific endonuclease (3,8). SMARCAL1 deficiency also causes increased sensitivity to replication stress agents like hydroxyurea (HU) and camptothecin, as well as an inability of stalled replication forks to recover DNA synthesis (3,4,6). Overexpression of SMARCAL1 causes replication-associated DNA damage, and lack of proper regulation causes fork collapse (3,15). Thus, either too much or too little SMARCAL1 activity causes genome instability during S-phase.

SMARCAL1 is phosphorylated in cells and hyper-phosphorylated in response to replication stress (3,16). Phosphorylation by ATM and RAD3-related protein kinase (ATR) on S652 decreases SMARCAL1 activity (15). To understand how additional phosphorylation events regulate its activity, we used mass spectrometry to identify phosphorylated residues. Here we describe our analysis of one of these sites, S889. Our data indicate that SMARCAL1 is phosphorylated at S889 even before cells are exposed to replication stress. S889 phosphorylation increases the ATPase and fork remodeling activities of SMARCAL1 likely by relieving an auto-inhibitory function of a C-terminal SMARCAL1 domain. Thus, S889 phosphorylation fine-tunes the activity of SMARCAL1 at replication forks to maintain genome integrity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and protein purification

HEK293T and U2OS cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 7.5% fetal bovine serum. HEK293T cell transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000. U2OS cell transfections were performed with Fugene HD. Flag-SMARCAL1 was purified from HEK293T cells following transient transfection or from insect cells after baculovirus infection as described previously (8). The S6 siRNA to SMARCAL1 was obtained from Dharmacon.

Mass spectrometry

Endogenous SMARCAL1 was purified from HEK293T cells treated with HU for 16 h by immunoprecipitation. After separation on sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels, the SMARCAL1 protein was excised from the gels, trypsinized and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry using an Orbitrap instrument. Candidate phosphopeptide spectra were validated manually.

DNA binding, ATPase and fork reversal assays

ATPase assays were performed as described previously with a splayed arm DNA substrate (8). Fork reversal assays were completed with 3 nM of gel purified, labeled fork reversal DNA substrate containing a leading strand gap and 3 nM of SMARCAL1 protein as previously described (11). DNA binding assays were performed with the leading strand gap substrate as previously described (11).

Antibodies

The rabbit polyclonal SMARCAL1 909 antibody has been described previously (3). The pS889 phosphopeptide-specific antibody was ordered from ThermoFisher and made using the following peptide antigen KIYDLFQK(pS)FEKE.

Immunofluorescence assays

For measuring SMARCAL1 localization, U2OS cells were transfected with GFP-SMARCAL1 expression vectors, plated onto glass coverslips, treated with 2 mM HU and then fixed and stained as previously described (3).

For measuring γH2AX levels after SMARCAL1 overexpression, U2OS cells were transfected and then seeded into 96-well CellCarrier plates (Perkin Elmer). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were washed once with phosphate buffered saline, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde solution and permeabilized with 0.5% triton X-100 for 10 min at 4°C. Fixed cells were then incubated with mouse anti-γH2AX antibody followed by Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody. After washing, the cells were incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride and then imaged on an Opera automated confocal microscope (Perkin Elmer) using a 20× water immersion objective. Columbus software (Perkin Elmer) was used to define nuclei and calculate the mean intensities per nucleus for green fluorescent protein (GFP) and γH2AX.

RESULTS

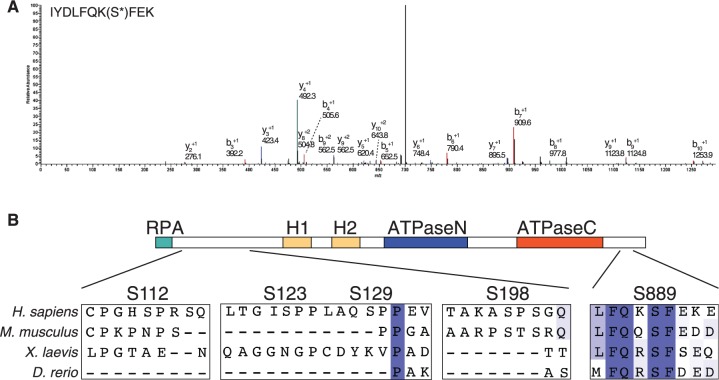

Identification of SMARCAL1 phosphorylation sites

To understand how SMARCAL1 is regulated by post-translational modifications, we purified the protein from cells treated with HU and identified phosphopeptides by mass spectrometry. This analysis identified six phosphorylated serines: S112, S123, S129, S198, S652 and S889 (Table 1 and Figure 1A). A phosphopeptide with phosphorylation on either S172 or S173 was also identified but the fragmentation of the peptide was consistent with phosphorylation on either serine. S112, 123, 120 and 198 are proline-directed SP sites and are poorly evolutionarily conserved (Figure 1B and data not shown). S173 and S652 match the consensus for the ATR family of checkpoint kinases, and our analysis of these sites is described in a separate publication (15). S889 is highly conserved throughout evolution but does not match the consensus for the ATR family kinases (Figure 1B). Therefore, we focused on this site for functional analyses.

Table 1.

SMARCAL1 phosphorylation sites identified by mass spectrometry

| Phosphorylation site | Peptide identified by MS |

|---|---|

| S112 | KPEEMPTACPGHS*PR |

| S123, S129 | SQMALTGIS*PPLAQS*PPEVPK |

| S129 | SQMALTGISPPLAQS*PPEVPK |

| S172 or S173 | (SS)*QETPAHSSGQPPR |

| S198 | AS*PSGQNISYIHSSSESVTPR |

| S652 | LKSDVLS*QLPAK |

| S889 | IYDLFQKS*FEK |

SMARCAL1 was purified from human cells, trypsinized and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry to identify phosphorylated residues. The fragmentation of the peptide containing S172 and S173 could not distinguish which of these residues were phosphorylated.

Figure 1.

SMARCAL1 is phosphorylated on S889, which is evolutionarily conserved. (A) The spectrum of a S889 phosphopeptide is shown. (B) An alignment of SMARCAL1 from four species shows that S889, unlike several other phosphorylated residues, is conserved in many other species. The location of the phosphorylation sites with respect to identified domains (RPA binding, HARP1 and HARP2 and ATPase) is diagramed.

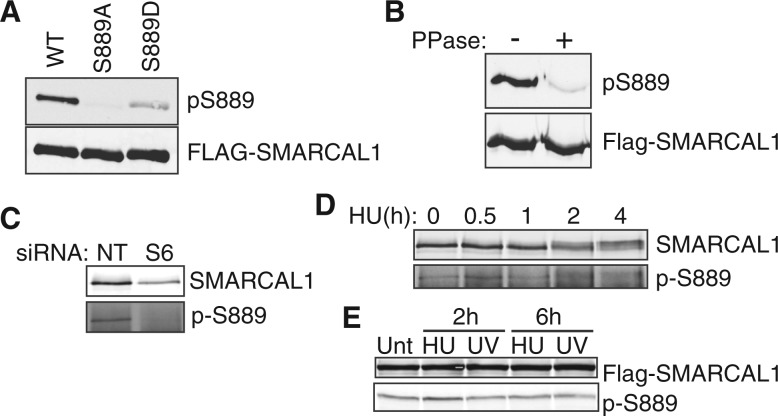

We raised a phosphopeptide-specific antibody to pS889. This antibody recognizes wild-type Flag-SMARCAL1 but not a S889A mutant, and it poorly recognizes an S889D mutant (Figure 2A). The antibody is specific to phosphorylated SMARCAL1, as phosphatase treatment of purified Flag-SMARCAL1 greatly reduces the signal on an immunoblot (Figure 2B). It also recognizes endogenous SMARCAL1, although only after immunoprecipitation with total SMARCAL1 antibody to enrich for the protein (Figure 2C). Knocking down SMARCAL1 with a SMARCAL1 siRNA (S6) reduces detection indicating specificity. SMARCAL1 phosphorylation is visible before and after treating cells with HU (Figure 2D and E). There are no large reproducible changes in phosphorylation in HU or ultraviolet (UV) light-treated cells. Thus, S889 is phosphorylated even in undamaged cells.

Figure 2.

Characterization of S889 phosphorylation using a phosphopeptide-specific antibody. (A) Flag-SMARCAL1 wild-type (WT), S889A or S889D proteins were expressed in HEK293T cells, immunoprecipitated and examined by immunoblotting with the pS889 or Flag antibodies. (B) Flag-SMARCAL1 was immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells and treated with lambda phosphatase as indicated before immunoblotting. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with non-targeting (NT) or SMARCAL1 (S6) siRNAs. SMARCAL1 immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with SMARCAL1 or pS889 antibodies to confirm specificity. (D) HEK293T cells were treated with 2 mM HU for the indicated times. SMARCAL1 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and immunoblotted. HU treatment induces a SMARCAL1 gel mobility shift but pS889 is present both before and after HU treatment. (E) U2OS cells expressing Flag-SMARCAL1 were treated with 2 mM HU or 50 J/m2 UV as indicated before immunoblotting for SMARCAL1 or pS889. (Unt, untreated) Small differences in phosphorylation were not reproducible in multiple experiments.

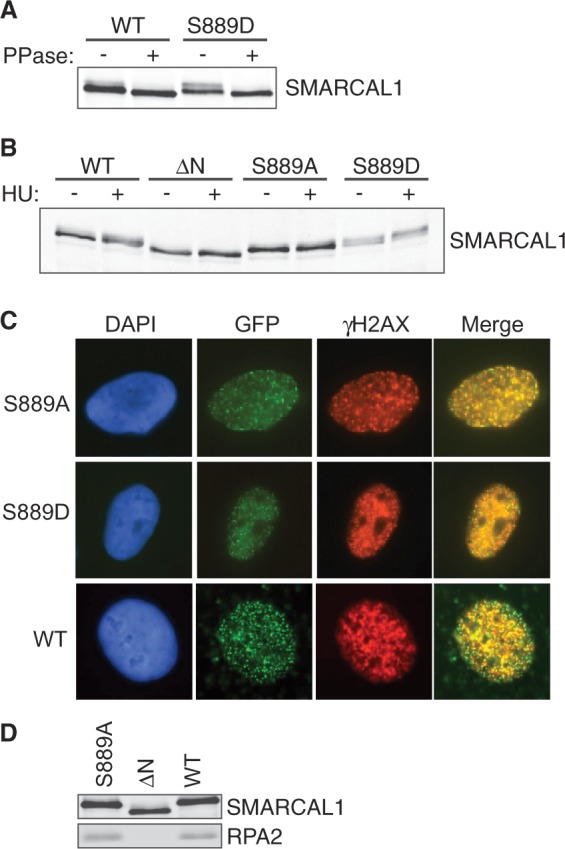

Mutation of S889 alters SMARCAL1 phosphorylation on other residues

To study the function of S889 phosphorylation, we expressed both S889A non-phosphorylatable and S889D phosphomimetic mutants in cells. We consistently observed that the S889D mutant migrated differently than the wild-type or S889A protein on SDS-PAGE gels. Specifically, a greater proportion of the S889D protein exhibits retarded mobility on SDS-PAGE gels and migrates as two distinct bands (Figure 3A and B). The slower migrating band disappears after phosphatase treatment, suggesting that this particular banding pattern results from additional phosphorylation of the protein (Figure 3A). The slower migrating band is more pronounced with the S889D mutant suggesting that phosphorylation of S889 shifts the equilibrium of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation on other sites to favor phosphorylation.

Figure 3.

S889 phosphorylation regulates the damage-induced phosphorylation of SMARCAL1 in cells without altering its localization. (A) Flag-SMARCAL1 wild-type or S889D proteins purified from HEK293T cells were incubated with lambda phosphatase as indicated, separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a total SMARCAL1 antibody. (B) GFP-SMARCAL1 proteins were expressed in HEK293T cells at levels close to endogenous SMARCAL1. Cells were treated with HU for 16 h where indicated and total cell lysates were immunoblotted with SMARCAL1 antibodies. [ΔN = RPA-binding mutant (3)] (C) GFP-SMARCAL1 wild-type, S889A or S889D protein expressing U2OS cells were treated with HU for 5 h, fixed and stained with antibodies to γH2AX. Shown are representative images of cells with co-localized foci. Quantitative measurements found no significant difference in the percentage of cells with GFP-SMARCAL1 S889A, S889D or wild-type foci. (D) Flag-Wild-type, ΔN or S889A SMARCAL1 protein was immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells. Immunoprecipitated protein complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with SMARCAL1 or RPA2 antibodies.

In line with this idea, we previously showed that the phosphorylation-dependent gel mobility shift of SMARCAL1 on SDS-PAGE gels is dependent on added DNA damage and DNA damage-activated kinases (3). The wild-type SMARCAL1 protein is shifted on SDS-PAGE gels when isolated from HU-treated cells (Figure 3B). In contrast, the S889A mutant has very little shift similar to the ΔN protein (Figure 3B). The ΔN protein cannot localize to stalled forks, as it does not bind RPA (3). However, the reduction of damage-induced phosphorylation on the S889A protein is not because it fails to bind RPA and localize to stalled forks, as both the S889A and S889D mutants localize to foci and bind RPA the same as the wild-type protein (Figure 3C and D). Thus, the status of S889 phosphorylation influences the amount of damage-regulated SMARCAL1 phosphorylation independent of its localization.

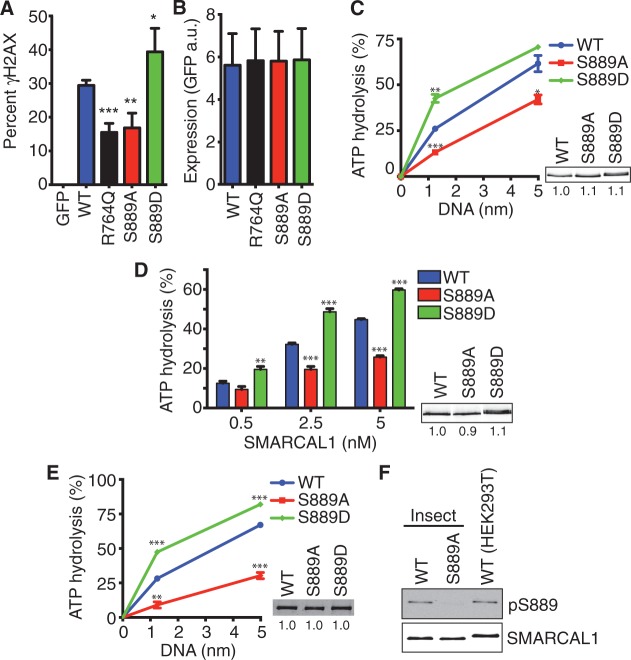

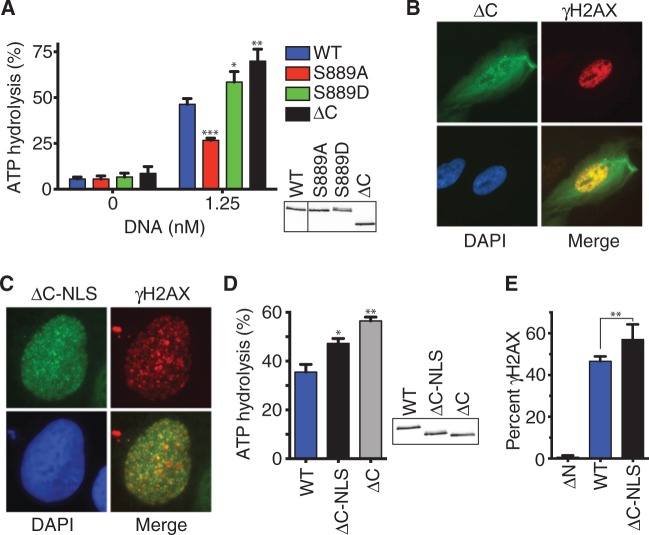

S889 phosphorylation activates SMARCAL1

We next investigated how S889 phosphorylation affects DNA damage signaling in cells. As we observed previously, overexpression of wild-type GFP-SMARCAL1 causes hyper-H2AX phosphorylation (γH2AX) in replicating cells (Figure 4A). A mutation that inactivates the ATPase activity of SMARCAL1 (R764Q) alleviates, although does not eliminate this phenotype. The SMARCAL1 S889A mutant behaves similarly to the R764Q protein, while the phosphomimetic S889D causes increased γH2AX (Figure 4A). The differences in γH2AX were not due to differences in expression level, as equal amounts of the proteins were expressed (Figure 4B), and we further controlled for the amount of expression on a cell-by-cell basis by only scoring γH2AX in cells with similar GFP fluorescence levels.

Figure 4.

S889 phosphorylation regulates SMARCAL1 ATPase activity. (A and B) U2OS cells were transfected with GFP-SMARCAL1 expression vectors and seeded in 96-well plates. Two days after transfection, the cells were fixed and stained with γH2AX antibodies and DAPI. Cells were imaged using an Opera automated confocal microscope and the GFP and γH2AX intensities per nucleus were measured using Columbus image analysis software. (A) The percentage of cells expressing GFP-SMARCAL1 with γH2AX intensity >1000 is graphed. Error bars are standard deviation (n = 7 wells for each of three biological replicates). ***P = 0.0008; **P = 0.003; *P = 0.04; two-tailed unpaired t-test comparing wild-type with each mutant. (B) The expression level as measured by GFP intensity is graphed. (C and D) The ATPase activity of Flag-SMARCAL1 purified from HEK293T cells was measured as a function of (C) fork DNA concentration or (D) SMARCAL1 concentration. The insets are representative immunoblots of the purified proteins used in the ATPase assays. Error bars are standard deviation (n = 3). In addition to a statistical difference between the overall curves, we calculated P-values for individual DNA or protein concentrations comparing wild-type with the mutant proteins. In (C) *P = 0.02; **P = 0.002; ***P = 0.0003; in (D) **P = 0.003; ***P < 0.0001. (E) The ATPase activity of Flag-SMARCAL1 proteins purified from baculovirus-infected insect cells in the presence of fork DNA was measured. **P = 0.0002, ***P < 0.0001. The inset is the Coomassie-stained gel of the purified proteins. (F) Flag-SMARCAL1 proteins purified from insect or human cells were immunoblotted with pS889 or total SMARCAL1 antibodies. The protein purified from human cells is slightly larger than the recombinant protein purified from insect cells due to extra amino acids encoded by the Gateway mammalian cell expression vector.

These data suggest that S889 phosphorylation might regulate the activity of the SMARCAL1 enzyme. To test this hypothesis more directly, we purified wild-type S889A and S889D proteins from human cells. DNA-stimulated ATPase activity was measured with increasing concentrations of a splayed arm DNA substrate. The S889A protein has significantly less ATPase activity compared with wild-type, whereas the S889D mutant has significantly more (Figure 4C). Similar differences are observed when holding the DNA concentration constant and performing the assay with increasing concentrations of SMARCAL1 protein (Figure 4D).

In these experiments, we consistently observed the gel mobility shift of the purified S889D mutant indicating hyper-phosphorylation (Figure 4C and D, inset). The hyper-phosphorylation is unlikely to cause the change in activity because wild-type SMARCAL1 purified from cells treated with HU to induce hyper-phosphorylation is actually less active than the protein purified from undamaged cells, and damage-induced phosphorylation decreases SMARCAL1 activity (15). To test this more directly, we purified the S889D mutant from baculovirus-infected insect cells. The S889D protein purified from insect cells does not exhibit hyperphosphorylation and migrates similarly to the wild-type protein on SDS-PAGE gels (Figure 4E, inset). Nonetheless, the S889D protein purified from insect cells did retain increased ATPase activity compared with wild-type SMARCAL1, suggesting that the mutation itself is the cause of the difference in activity rather than an indirect effect on another phosphorylation site. In addition, the S889A SMARCAL1 protein purified from insect cells is less active than the wild-type protein. If S889 phosphorylation regulates SMARCAL1 activity then this result predicts that SMARCAL1 is partially phosphorylated on S889 when expressed in insect cells. As expected the phosphopeptide-specific antibody to pS889 recognizes the insect cell-purified SMARCAL1 as efficiently as SMARCAL1 purified from human cells (Figure 4F).

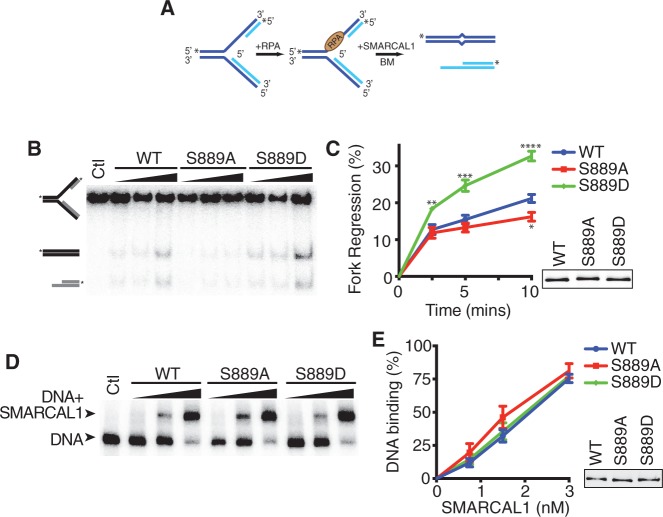

To determine whether the change in ATPase activity when S889 is phosphorylated results in a change in SMARCAL1 function, we assayed the ability of SMARCAL1 to catalyze replication fork regression. For this analysis, we used the preferred SMARCAL1 substrate containing RPA bound to a leading strand gap [Figure 5A and (11)]. As expected, the phosphomimetic S889D mutant is significantly more active in catalyzing fork regression than the wild-type protein. The S889A mutant is also slightly less active than wild-type. The differences in ATPase and fork regression activities do not stem from a difference in the ability of the S889A or S889D proteins to bind DNA, as there are no significant differences in binding to the fork regression substrate (Figure 5D and E).

Figure 5.

S889 phosphorylation regulates SMARCAL1 fork regression activity. (A) A schematic representation of the fork regression assay is shown. A leading-strand gap fork with RPA bound was used as the substrate. BM, branch migration. (B) A representative gel showing the results of the regression assay is shown. Ctl, control with no protein added during the reaction to monitor spontaneous branch migration. (C) Quantitative analysis of three replicates of the fork regression assay. *P = 0.036; **P = 0.02; ***P = 0.009; ****P = 0.003. (D) The RPA-bound leading-strand gap fork substrate was incubated with increasing concentrations of SMARCAL1 proteins before separation of DNA complexes on a native polyacrylamide gel. A representative image of a DNA binding assay is shown. (E) Quantitative analysis of three replicates of the DNA binding assay. The insets in (C and E) are immunoblots of the SMARCAL1 proteins purified from insect cells.

S889 phosphorylation relieves auto-inhibition of SMARCAL1 by a C-terminal domain

S889 lies within an evolutionarily conserved C-terminal region of SMARCAL1 but outside of any known domains including the ATPase domain. We considered the possibility that S889 participates in some part of enzyme catalysis. If true, we would expect that deletion of the C-terminus containing S889 would inactivate the SMARCAL1 enzyme. However, truncating SMARCAL1 by deleting amino acids 861–954 (ΔC) generated an enzyme that is actually hyperactive with even greater ATPase activity than the S889D protein (Figure 6A). When expressed in cells, the ΔC protein retains the ability to localize to foci within the nucleus of HU-treated cells. However, in contrast to the other mutants analyzed, it also partially localizes to the cytoplasm (Figure 6B). This aberrant localization could potentially explain why the purified protein does not migrate as two bands on SDS-PAGE gels like the S889D protein (Figure 6A, immunoblot insert). To test this idea and also rule out the possibility that the ΔC protein is only more active than the wild-type protein because it is purified from cells in which a large proportion of it is localized to the cytoplasm, we added a nuclear localization signal (NLS) to the cDNA. This forced the ΔC protein to localize exclusively to the nucleus (Figure 6C). It also caused increased phosphorylation as evidenced by a slight gel mobility shift on SDS-PAGE gels (Figure 6D, inset). Importantly, the purified ΔC-NLS protein is also more active than wild-type SMARCAL1, although it is slightly less active than the ΔC protein without the NLS. The small difference in activity between the ΔC-NLS and ΔC proteins likely results from the difference in damage-induced phosphorylation levels on the two proteins, as increased phosphorylation of the ΔC-NLS protein by ATR on S652 would tend to decrease its activity (15).

Figure 6.

The C-terminal region of SMARCAL1 containing S889 is an auto-inhibitory domain. (A) Flag-SMARCAL1 proteins were purified from HEK293T cells and examined for ATPase activity. *P = 0.031; **P = 0.005; ***P = 0.0005. (B and C) U2OS cells expressing GFP-SMARCAL1-ΔC were treated with HU for 5 h, fixed and stained with antibodies to γH2AX and Flag. (C) U2OS cells expressing Flag-NLS-SMARCAL1-ΔC were treated with HU for 5 h, fixed and stained with antibodies to γH2AX and Flag. (D) The ATPase activities of Flag-SMARCAL1 proteins purified from HEK293T were examined in the presence of forked DNA. *P = 0.04; **P = 0.003. The insets in (A) and (D) are immunoblots of the purified proteins. (E) U2OS cells were transfected with FLAG-SMARCAL1 expression vectors and seeded onto coverslips. Two days after transfection the cells were fixed and stained with γH2AX and FLAG antibodies. Cells expressing Flag-SMARCAL1 proteins were scored for pan-nuclear γH2AX staining. Error bars denote standard deviation (n = 6). **P = 0.007; two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Finally, if the C-terminus is an auto-inhibitory domain, then deletion of this domain should cause even greater pan-nuclear H2AX phosphorylation when overexpressed in cells than overexpression of the wild-type protein. Indeed, there is a significant difference as predicted (Figure 6E). Overall, these data suggest that the C-terminal region is an auto-inhibitory domain that restrains SMARCAL1 activity. Phosphorylation of the domain on S889 likely relieves this auto-inhibition.

DISCUSSION

SMARCAL1 is important to maintain genome integrity in response to replication stress. The DNA annealing and branch migration activities of SMARCAL1 allow it to catalyze fork regression and fork restoration in reactions regulated by its interaction with RPA (8,11). Although these activities are important to promote fork repair and restart, they must be regulated to ensure the right level of activity. Too much or too little SMARCAL1 activity is detrimental to genome stability, as fork-associated damage accumulates in replicating cells when SMARCAL1 is silenced or overexpressed (3,15,17). Our data indicate that one mechanism of SMARCAL1 regulation is through phosphorylation of an auto-inhibitory domain. Phosphorylation of S889 likely relieves SMARCAL1 inhibition resulting in increased DNA-stimulated ATPase and branch migration activities. Interestingly, this is the opposite of how phosphorylation at S652 regulates SMARCAL1 (15). Thus, phosphorylation in undamaged cells at S889 promotes its activity, whereas phosphorylation at S652 after persistent replication stress decreases its activity. Together, these phosphorylation events help ensure that the level of SMARCAL1 fork remodeling activity needed to repair damaged forks is available without jeopardizing genome stability.

As yet it is not clear in what contexts S889 phosphorylation is regulated. We have not observed consistent changes in response to several different DNA-damaging agents at different time points. We also did not observe changes in cell cycle synchronized cells or in several cell types. It may be that S889 phosphorylation is regulated by a different input than DNA damage, changes in phosphorylation may happen on only a subset of the protein in the cell (such as the protein at a stalled fork), the changes in phosphorylation may be too rapid to observe when examining total SMARCAL1, its regulation may be perturbed in the cells or growth conditions we have used for these experiments or different cell types or tissues may have different levels of SMARCAL1 phosphorylation.

SMARCAL1 belongs to the SNF2 family, which is a subset of SF2 helicase proteins. These proteins share similar ATPase motor domains flanked by accessory domains that determine their specificity and impart unique functions and regulation. In some cases, these accessory domains can block nucleic acid binding or influence the mobility of the ATPase domain lobes. For example, the chromodomains of the CHD1 SNF2 protein regulate the ability of its ATPase domain to bind to DNA (18). We did not observe a difference in the abilities of the S889D and S889A proteins to bind to DNA. Also, the S889D mutation did not remove the nucleic acid binding requirement for SMARCAL1 activity. Thus, we favor a model in which phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain changes its ability to block the activity of the ATPase domain. This mechanism resembles how an N-terminal helix of the SF2 protein DDX19 regulates its activity by binding between its two ATPase domains and preventing the formation of an active conformation (19). Also, the SNF2 proteins CHD1 and ISWI contain auto-inhibitory domains that regulate their activities (18,20). Thus, auto-inhibition may be a common regulatory mechanism for this family of DNA translocases.

Although our data are consistent with a model of the SMARCAL1 C-terminus acting as an auto-inhibitory domain, we have not yet observed SMARCAL1 inhibition when a recombinant SMARCAL1 C-terminal fragment is added to wild-type SMARCAL1 ATPase assays in trans (data not shown). Thus, we cannot completely rule out other models. For example, in principle, phosphorylation of the C-terminus could regulate the binding of SMARCAL1 to a regulatory protein. However, we do not favor that model because S889 phosphorylation changes the activity of highly purified recombinant SMARCAL1 and we have not detected any differences in the association of the S889A or S889D proteins with known interacting proteins like RPA and WRN (17).

The S889D SMARCAL1 protein is hyper-phosphorylated on other sites in cells. This hyper-phosphorylation also occurs on wild-type SMARCAL1 in cells treated with DNA-damaging agents and is dependent on the checkpoint kinases ATR, ATM and DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs) (3). The increased phosphorylation may be due to the activation of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs kinases caused by the increased DNA damage in cells overexpressing the hyperactive S889D mutant. This hyper-phosphorylation does not explain the increased activity of the S889D mutant, as the S889D protein purified from insect cells is not hyper-phosphorylated but is hyperactive. In addition, the ΔC-SMARCAL1 protein expressed largely in the cytoplasm is also hyperactive but lacks hyper-phosphorylation. In fact, the hyper-phosphorylation may partially mask the increased activity of the S889D and NLS-ΔC-SMARCAL1 proteins, as damage-dependent phosphorylation reduces SMARCAL1 activity (15). The hyper-phosphorylation of the S889D mutant and reduced HU-induced phosphorylation of the S889A mutant is consistent with the model that damage-dependent phosphorylation of SMARCAL1 happens only after it performs some activity at the stalled replication fork (15).

In summary, we have identified an auto-inhibitory domain of SMARCAL1 and shown that phosphorylation of this domain regulates its enzymatic activity. Although additional studies will be needed to identify the kinase that phosphorylates S889 and understand its regulation, our results indicate that this phosphorylation helps ensure that the right level of fork remodeling activity is present to repair damaged replication forks.

FUNDING

The National Institutes of Health [CA136933 to D.C]. Insect cell expression was supported by the Structural Biology of DNA Repair program project [CA092584]. The St. Baldrick’s Foundation [to C.C.] and funding for the Vanderbilt Proteomics Core was provided by the Center in Molecular Toxicology [ES000267] and the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health [CA136933].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Miaw-Sheue Tsai for the production of baculoviruses and for protein expression in insect cells.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cimprich KA, Cortez D. ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:616–627. doi: 10.1038/nrm2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branzei D, Foiani M. Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;11:208–219. doi: 10.1038/nrm2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansbach CE, Betous R, Lovejoy CA, Glick GG, Cortez D. The annealing helicase SMARCAL1 maintains genome integrity at stalled replication forks. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2405–2414. doi: 10.1101/gad.1839909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciccia A, Bredemeyer AL, Sowa ME, Terret ME, Jallepalli PV, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. The SIOD disorder protein SMARCAL1 is an RPA-interacting protein involved in replication fork restart. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2415–2425. doi: 10.1101/gad.1832309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusufzai T, Kong X, Yokomori K, Kadonaga JT. The annealing helicase HARP is recruited to DNA repair sites via an interaction with RPA. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2400–2404. doi: 10.1101/gad.1831509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan J, Ghosal G, Chen J. The annealing helicase HARP protects stalled replication forks. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2394–2399. doi: 10.1101/gad.1836409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusufzai T, Kadonaga JT. HARP is an ATP-driven annealing helicase. Science. 2008;322:748–750. doi: 10.1126/science.1161233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betous R, Mason AC, Rambo RP, Bansbach CE, Badu-Nkansah A, Sirbu BM, Eichman BF, Cortez D. SMARCAL1 catalyzes fork regression and Holliday junction migration to maintain genome stability during DNA replication. Genes Dev. 2012;26:151–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.178459.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hockensmith JW, Wahl AF, Kowalski S, Bambara RA. Purification of a calf thymus DNA-dependent adenosinetriphosphatase that prefers a primer-template junction effector. Biochemistry. 1986;25:7812–7821. doi: 10.1021/bi00372a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciccia A, Nimonkar AV, Hu Y, Hajdu I, Achar YJ, Izhar L, Petit SA, Adamson B, Yoon JC, Kowalczykowski SC, et al. Polyubiquitinated PCNA Recruits the ZRANB3 Translocase to Maintain Genomic Integrity after Replication Stress. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:396–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betous R, Couch FB, Mason AC, Eichman BF, Manosas M, Cortez D. Substrate-selective repair and restart of replication forks by DNA translocases. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1958–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boerkoel CF, Takashima H, John J, Yan J, Stankiewicz P, Rosenbarker L, Andre JL, Bogdanovic R, Burguet A, Cockfield S, et al. Mutant chromatin remodeling protein SMARCAL1 causes Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:215–220. doi: 10.1038/ng821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baradaran-Heravi A, Raams A, Lubieniecka J, Cho KS, DeHaai KA, Basiratnia M, Mari PO, Xue Y, Rauth M, Olney AH, et al. SMARCAL1 deficiency predisposes to non-Hodgkin lymphoma and hypersensitivity to genotoxic agents in vivo. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2012;158A:2204–2213. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll C, Badu-Nkansah A, Hunley T, Baradaran-Heravi A, Cortez D, Frangoul H. Schimke Immunoosseous Dysplasia associated with undifferentiated carcinoma and a novel SMARCAL1 mutation in a child. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2013;60:E88–90. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couch FB, Bansbach CE, Driscoll R, Luzwick JW, Glick GG, Betous R, Carroll CM, Jung SY, Qin J, Cimprich KA, et al. ATR phosphorylates SMARCAL1 to prevent replication fork collapse. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1610–1623. doi: 10.1101/gad.214080.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Postow L, Woo EM, Chait BT, Funabiki H. Identification of SMARCAL1 as a component of the DNA damage response. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:35951–35961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.048330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betous R, Glick GG, Zhao R, Cortez D. Identification and Characterization of SMARCAL1 Protein Complexes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauk G, McKnight JN, Nodelman IM, Bowman GD. The chromodomains of the Chd1 chromatin remodeler regulate DNA access to the ATPase motor. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:711–723. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins R, Karlberg T, Lehtio L, Schutz P, van den Berg S, Dahlgren LG, Hammarstrom M, Weigelt J, Schuler H. The DEXD/H-box RNA helicase DDX19 is regulated by an {alpha}-helical switch. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:10296–10300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C900018200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clapier CR, Cairns BR. Regulation of ISWI involves inhibitory modules antagonized by nucleosomal epitopes. Nature. 2012;492:280–284. doi: 10.1038/nature11625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]