Abstract

Background:

Although combined oral and nasal steroid therapy is widely used in nasal polyposis, a subset of patients show an unfavorable therapeutic outcome. This study aimed to evaluate whether oral prednisolone produces any additive effects on subsequent nasal steroid therapy and to evaluate if any clinical variables can predict therapeutic outcome.

Methods:

Using a 3:2 randomization ratio, 67 patients with nasal polyposis received 50 mg of prednisolone and 47 patients received placebo daily for 2 weeks, followed by mometasone furoate nasal spray (MFNS) at 200 micrograms twice daily for 10 weeks. Clinical response was evaluated by nasal symptom score (NSS), peak expiratory flow index (PEFI), and total nasal polyps score (TNPS). Potential predictor variables were assessed by clinical history, nasal endoscopy, allergy skin test, and sinus radiography.

Results:

At the end of the 2-week oral steroid phase, the prednisolone group showed significantly greater improvements in all nasal symptoms, nasal airflow, and polyp size than the placebo group. In the nasal steroid phase, while the MFNS maintained the outcome improvements in the prednisolone group, all outcome variables in the placebo group showed continuing improvements. At the end of the nasal steroid phase, there were no significant differences of most outcome improvements between the two groups, except in hyposmia, PEFI, and TNPS (p = 0.049, p = 0.029, and p = 0.005, respectively). In the prednisolone group, patients with polyps grade 3 and endoscopic signs of meatal discharge showed significantly less improvement in total NSS, PEFI, and TNPS than patients with grade 1–2 size and negative metal discharge.

Conclusion:

In the 12-week treatment evaluation of nasal polyposis, pretreatment with oral steroids had no significant advantage for most nasal symptoms other than earlier relief; however, combined oral and nasal steroid therapy more effectively improved hyposmia, polyps size, and nasal airflow. Polyps size grade 3 and/or endoscopic signs of meatal discharge predisposed to a poorer treatment outcome.

Keywords: Nasal polyposis, nasal steroids, nasal symptom, oral steroids, peak expiratory flow index, placebo, polyps size, predictor, randomization, therapeutic outcome

Nasal polyposis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the sinonasal mucosa of unknown etiology, which can have a major effect on quality of life.1 Although nasal steroids are the mainstay treatment and have a documented positive effect on nasal symptoms and polyp size,2 up to one-half of patients do not respond to this approach and need surgical treatment.3,4 The efficacy of systemic steroids in dramatic reduction of symptoms and polyp size is well known; however, there are also significant side effects if used in the long term. The optimum systemic steroid usage without significant side effects is clinically important because it may improve overall medical treatment efficacy. Although a short course of oral prednisolone administration before nasal steroids has been used to induce a rapid reduction in polyp size, facilitating the ability of nasal steroids to gain access to the polypoid tissue,5–8 data to confirm the additive effects of oral steroids on long-term efficacy of topical steroid therapy in the treatment of nasal polyposis are lacking.

Even with the promising effect of this dual modality in clinical practice, a certain number of nasal polyp patients have a poor response to this conservative approach and up to 31.5% still need surgical treatment.9,10 Nasal polyposis is a multifactorial disease, in which interaction of different predisposing factors and comorbid disorders may have an impact on treatment outcome. Potential contributing factors include allergy, sinusitis, asthma, aspirin intolerance, and size of polyps. Whether nasal polyps with any or some of these external factors are less sensitive to steroid therapy than cases without any of these factors is still a controversial issue. A number of recent studies have found that nasal polyp patients with one or more of these factors have a poor response to steroid therapy and a higher recurrence rate after surgery.11–20 However, these results may be questioned because most of these studies were retrospective in design and, to date, there has been no direct comparative study to evaluate the direct effects of these factors on the therapeutic response of combined oral and nasal steroids in nasal polyposis. Knowledge of the effects of these possibly predicative variables would be useful in treatment planning and identifying patients most likely to benefit from early surgical intervention in nasal polyposis.

We previously evaluated the efficacy of a 14-day course of 50 mg of oral prednisolone in nasal polyposis. The study showed the positive effects of a short course of corticosteroids on improvements in nasal symptoms, polyps size, and nasal airflow; however, patients with large polyp size and/or mucoid or mucopurulent discharge from the middle meatus or superior meatus were predisposed to a poorer treatment outcome.21 In that study, we evaluated the short-term effects of systemic steroids at 14 days posttrial in nasal polyposis. Whether systemic steroids has an augmented effect on subsequent nasal steroid therapy and whether predictive variables change after this dual modality are two important questions in clinical practice. In an attempt to shed some light on these issues, we extended the clinical trial to an additional 10 weeks of nasal steroid therapy after 2 weeks of oral steroid therapy. We aimed to investigate the hypothesis that an initial administration of a short course of oral prednisolone would lead to more efficacious results from subsequent nasal steroid therapy in the treatment of nasal polyposis. We further examined the data for any association between possible predictive variables, e.g., demographic data, history of aspirin sensitivity, asthma, allergy skin test and sinusitis, and therapeutic response to this dual modality.

METHODS

The study was conducted on 117 patients with nasal polyposis at the Allergy and Rhinology Clinic, Department of Otolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, Songklanagarind Hospital, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand, between May 1, 2007 and September 30, 2010. Five new patients and all 112 patients who participated in our previous study21 were recruited into the study. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University. All patients gave their signed, informed consent before being recruited into the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients with benign bilateral nasal polyps diagnosed clinically and confirmed by nasal endoscopy were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had symptoms or physical signs suggestive of renal disease, hepatic disease, diabetes mellitus, cataract, glaucoma, cardiovascular disease, unstable asthma, cystic fibrosis, mucociliary disorders, immunocompromise, severe septal deviation, or acute infection within the previous 2 months. Patients who had used nasal, inhaled, or systemic steroids within 2 months; an antihistamine within 2–7 days; and/or a decongestant within 2 days or had had previous sinonasal surgery were also excluded from the study.

Data Collection

The medical history of each subject, including age, sex, nasal symptoms, concomitant diseases, and medication use, was recorded. The diagnosis of aspirin intolerance was made based on a clear-cut history of asthma attacks precipitated by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Asthma was noted if the patient had a history of recurrent wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, or cough (particularly at night), and a normal chest x ray. The criteria for diagnosis of rhinosinusitis were rhinitis symptoms (nasal blockage, rhinorrhea/postnasal drip, facial pain/pressure, and hyposmia), positive meatal discharge (endoscopic signs of mucoid or mucopurulent discharge from the middle meatus or superior meatus), and/or positive sinus radiography (one or more abnormal finding on a plain film of the paranasal sinus (Caldwell and Waters view), e.g., haziness, opacity, air–fluid level, or mucosal thickening of >4 mm).

An allergy skin-prick test was performed with 18 common aeroallergens (Bermuda grass, Johnson grass, acacia, careless weed, Alternaria species, Aspergillus mix, Candida albicans, Penicillium mix, Fusarium, cat pelt, dog epithelium, mixed feathers, kapok, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, American cockroach, pyrethrum, and Cladosporium sphaerospermum; all from Allertech Co., Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand). Histamine phosphate at 2.75 mg/mL was used as a positive control and glycerin saline was used as a negative control. Skin wheal diameters were determined at 20 minutes using the mean of the longest diameter and the perpendicular midpoint diameter. A positive reaction was defined as a skin wheal diameter of at least 3 mm greater than the negative control skin wheal.

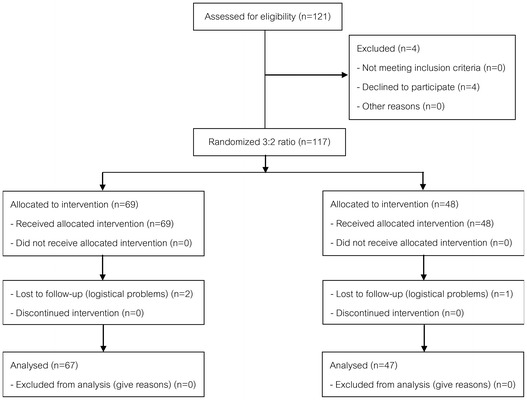

Patients were randomly assigned at a 3:2 ratio to receive 50 mg of prednisolone or placebo, respectively, daily for 14 days and were blinded to their treatment regimen. The dosage and duration of prednisolone were selected as the maximum safe dose that could be given to adults without inducing lasting adrenal suppression and allowing drug cessation without tapering.22,23 At the end of this preliminary stage, all patients were then treated with administration of mometasone furoate nasal spray (MFNS) at 200 μg twice daily for 10 weeks (Fig. 1). They were told that the use of other medications for rhinitis or allergy or nasal saline irrigation were not allowed during their participation in the study. The study personnel were not informed of the treatment modality of the patients until all assessments were completed. All patients were instructed to return their remaining drug at the 2-week follow-up visit and then record carefully each nasal steroid dose taken on a diary card, which they would bring at their 7- and 12-week follow-up visits. The patient's compliance with his/her study medication was defined as the percentage of the prescribed doses taken.

Figure 1.

Study design. Patients were 3:2 randomly assigned into two groups: group A received oral prednisolone followed by intranasal mometasone and group B received placebo followed by intranasal mometasone.

Clinical Assessment

Evaluations of the patients' symptoms were performed at the first visit before beginning treatment (week 0), at the end of the oral prednisolone phase (week 2), the middle of the MFNS treatment phase (week 7), and at the end of the MFNS treatment (week 12), based on scores assessing blocked nose, runny nose, sneezing, nasal itching, hyposmia, postnasal drip, cough, and sinonasal pain. The severity of each individual symptom was assessed with a 7-point Likert scale, with score 0 = no symptoms, score 1–2 = mild symptoms (steady symptoms but easily tolerable), score 3–4 = moderate symptoms (symptoms hard to tolerate, might interfere with activities of daily living, sleep, or both), and score 5–6 = severe symptoms (symptoms so bad that the person could not function virtually all the time). The sum of the individual nasal symptom scores gave the total nasal symptoms score (TNSS).

Nasal patency was assessed at each visit by testing with the nasal and oral peak expiratory flow index (PEFI). A Mini-Wright peak flowmeter (Clement Clarke International Ltd., London, U.K.) connected to an anesthetic face mask covering both nose and mouth, instead of a mouthpiece alone, was used for nasal PEF measurements. The patient was instructed to keep their lips tightly closed while performing the maximal total expiratory effort through the nose after a maximal inspiration. Peak flow rate was read from a cursor in liters per minute, with the best of three readings with a variation of <10% considered as the true peak flow, which was then recorded as the result. The PEFI was calculated as the nasal PEF divided by the oral PEF to compensate for changes in lung function.

Nasal polyps size was assessed by nasal endoscopy at each visit and scored on a scale of 0–3 as follows: score 0, no polyps; score 1, mild polyposis (small polyps, extending downward from the upper nasal cavity but not below the upper edge of the inferior turbinate, causing only slight obstruction); score 2, moderate polyposis (medium-sized polyps, extending downward from the upper nasal cavity and reaching between the upper and lower edges of the inferior turbinate, causing troublesome obstruction); and score 3, severe polyposis (large-sized polyps, extending downward from the upper nasal cavity and reaching below the lower edge of the inferior turbinate, causing total or almost total obstruction). The total nasal polyps score (TNPS) was calculated as the sum of the polyps scores for each nostril.

Statistical Analysis

The patients were randomized in favor of the prednisolone group in a 3:2 ratio because this was hypothesized to be ethically desirable to minimize the placebo exposure and also to better assess the potential predictive variables in the prednisolone group. A 3:2 randomization ratio has little loss of power (1%) and requires only a negligible increase in the sample size. This slightly unbalanced randomization has been considered in the power analysis below. The power calculation was based on polyp size reduction found with the two different regimens from a previous study.6 To have a two-tail significance test, a significance level of α = 0.05 and 90% power to detect a difference as small as 0.5, for a standard deviation of 0.72, and using an allocation of 3:2 for the prednisolone and placebo groups while allowing for a 20% dropout rate, the study required at least 66 patients to be treated with prednisolone and 44 to be treated with placebo. To compensate for the reduction of power, 69 patients for the prednisolone group and 48 for the placebo group were enrolled in the study.

Demographic data comparisons between the groups were made using the chi-square test. The Komolgorov-Smirnov test was used to test continuous variables for any deviations from normality. In comparisons of percentage changes in nasal symptom scores, PEFI, and TNPS between the groups, the unpaired t-test was used for parametric data and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonparametric data. In the prednisolone group, the differences of percentage improvements in TNSS, PEFI, and TNPS at the end of the trial, 12 weeks after beginning treatment, between nasal polyp patients with positive and negative prognostic factors were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test and unpaired t-test, respectively. Variables statistically different between the positive and negative prognostic factor groups in the univariate analyses were included in a multiple linear regression analysis with stepwise entry of variables; the dependent variables were percentage changes in TNSS, PEFI, and TNPS to identify independent predictive factors of poor response to treatment with the combined oral and nasal steroid regimen. In all tests of significance, two-tailed alternatives were used. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Between May 1, 2007 and September 30, 2010, 117 patients were enrolled in the study. Sixty-nine and 48 patients were randomized into the prednisolone and placebo groups, respectively. Two patients in the prednisolone group and one patient in the placebo group did not attend their first follow-up visit because of logistical problems (Fig. 2). Baseline characteristics, including demographic characteristics, duration of symptoms, concomitant diseases, and baseline symptom data were similar in the two groups (Table 1). At the completion of the study, compliance with the study medication was essentially the same in each group for both the oral steroid (96.2 and 96.7%) and the nasal steroid phases (95.6 and 96.1%, for the prednisolone and placebo groups, respectively).

Figure 2.

Patient flow diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, comparing the prednisolone and placebo groups

PEFI = peak expiratory flow index; TNPS = total nasal polyp score.

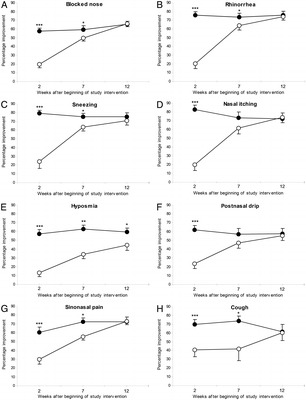

Nasal Symptoms

Figure 3 shows that at 2 weeks, the end of the oral steroid phase, those who had received prednisolone had significantly more improvements of all nasal symptoms than those who had only received a placebo (p < 0.001, all). During the following administration of nasal steroids to all participants, the MFNS maintained the improvements of most nasal symptoms in the prednisolone group, and the placebo group showed continuing improvements of all nasal symptoms. At 12 weeks, the end of the nasal steroid phase, there were no significant differences in the improvements of most nasal symptoms between the two groups, except in hyposmia (p = 0.049).

Figure 3.

Percentage changes from baseline in individual symptom scores during treatment period in prednisolone (closed circle) and placebo (open circle) groups: (A) blocked nose, (B) rhinorrhea, (C) sneezing, (D) nasal itching, (E) hyposmia, (F) postnasal drip, (G) sinonasal pain, and (H) cough. Data are shown as mean (SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared between the groups.

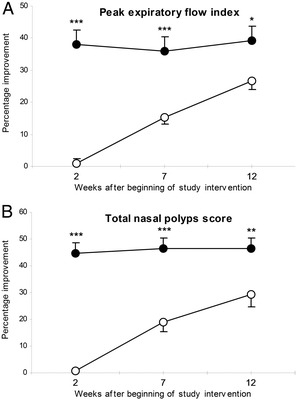

PEFI and Nasal Polyp Size

At 2 weeks, the end of the oral steroid phase, the prednisolone group showed significantly more improvements of both PEFI and nasal polyp size reduction than placebo group (p < 0.001, both). During the nasal steroid phase of the study, the MFNS group maintained the improvements of these objective outcomes in the prednisolone group and there were continuing improvements of PEFI and reduction of polyp size in the placebo group. The improvements of both PEFI scores and nasal polyp size in the prednisolone group were significantly higher than in the placebo group at the end of the study (p = 0.029 and p = 0.005; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage changes from baseline in (A) mean peak expiratory flow index (PEFI) and (B) total nasal polyps scores (TNPSs) during treatment period in prednisolone (closed circle) and placebo (open circle) groups. Data are shown as mean (SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.01, compared between the groups.

Adverse Effects

The study treatment regimens for nasal polyposis, of either oral prednisolone or placebo for the first 2 weeks, followed in both groups by MFNS, was well tolerated by all patients. The few adverse events reported during the study were of only mild or moderate intensity and no serious adverse events were reported. Gastrointestinal disturbances and dyspepsia were noted more frequently in the oral prednisolone group. Other side effects were similar in both groups and infrequent. No patient reported significant adverse symptoms during the days immediately after cessation of prednisolone. In the nasal steroid phase, the most frequent adverse effects reported in both groups were throat irritations, headache, and nasal irritation, with no significant differences between the two groups. There were no complaints of epistaxis or crusting during the treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of subjects with adverse events considered to be related to treatment

Potentially Predictive Factors on Treatment Outcome

To determine which clinical parameters might predict the therapeutic response to the combined oral and nasal steroid regimen, different hypothesized predictive variables were analyzed. Univariate analyses comparing these factors with treatment outcomes, indicated by percentage changes in TNSS, PEFI, and TNPS scores after the completion of treatment were performed to identify the factors to be included in the subsequent multivariate analysis. Among these factors, univariate analyses showed that patients with polyp grade 3 and positive meatal discharge showed less improvement in all treatment outcomes than patients with polyp grades 1 and 2 and negative meatal discharge (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis comparing percentage changes in TNSS, PEFI, and polyp size reduction with potentially predictive independent variables after combined oral and nasal steroid treatment

PEFI = peak expiratory flow index; TNSS = total nasal symptom score.

In a multiple linear regression analysis, using percentage changes in TNSS, PEFI, and TNPS scores as the dependent variables, we entered polyp grade and meatal discharge as independent predictive variables. In this analysis, both polyp grade and nasal endoscopy were significant predictors of treatment outcome, because the coefficient indicated that increasing polyp size or positive meatal discharge predicted poorer therapeutic response (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate linear regression analysis of potentially predictive variables with percentage improvements in TNSS, PEFI, and polyp size reduction after combined oral and nasal steroid treatment

PEFI = peak expiratory flow index; TNSS = total nasal symptom score.

DISCUSSION

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study examining the effect of initial oral prednisolone administration on subsequent nasal steroid treatment outcome in patients with nasal polyposis. The outcome measures included subjective assessment of nasal symptoms and objective measures including nasal airflow and polyp size. In the oral steroid phase, analysis of combined data from both our current and a previous study21 showed that both subjective and objective outcomes were clearly more improved at 2 weeks after the initial oral steroid treatment than with placebo administration. In the current extended study, in the prednisolone group, the treatment with nasal steroids maintained the improvement reached with oral steroids, while in the placebo group, both subjective and objective outcomes showed improvement over time with the nasal steroid treatment. At 12 weeks, the end of the nasal steroid phase, there were no significant differences in the improvements of most outcomes between the two groups with the exceptions of hyposmia, PEFI, and TNPS. Only the subjective outcomes of hyposmia showed significantly more improvement with prednisolone compared with the placebo group, in contrast to objective outcomes, which showed significantly greater improvements in all categories in the prednisolone group over the placebo group at the end of the study. Although an improvement in hyposmia was the only benefit noted with initial oral steroid treatment in subjective outcomes, the objective outcomes confirmed the additional treatment effect, at least in polyp size reduction and increased nasal airflow, of oral steroids on subsequent nasal steroids in nasal polyposis.

Olfactory dysfunction is a very annoying symptom and can significantly affect the quality of life in severe manifestations.24 Nasal polyposis causes olfactory dysfunction from mechanical obstruction and sensorineural defects.25,26 Overall, previous studies have indicated that the effect of nasal steroids, in contrast to systemic administration, seems to be poor.27–29 Our study also showed a more refractory response to nasal steroid treatment of olfactory dysfunction than other nasal symptoms. Olfactory dysfunction was more clearly improved after a short course of oral prednisolone, and this effect was maintained with nasal steroids up to 10 weeks after the initial 2-week oral steroid treatment. This dramatic restoration of olfactory function with the oral steroids indicates that these drugs have a direct anti-inflammatory effect on the olfactory mucosa. However, the sustained improvement of olfaction in the prednisolone group and the tendency to improve olfaction in the placebo group after nasal steroid therapy suggest that a reduction in polyp size and mucosal inflammation in conductive mechanism is another important mechanism.

In this study, although the combined oral and nasal steroid treatment showed good therapeutic effects, a certain number of nasal polyp patients showed limited clinical improvement. Patients with polyp size grade 3 or positive meatal discharge had worse therapeutic responses than nasal polyp patients with polyp size grade 1–2 or negative meatal discharge. In clinical practice, large nasal polyposis generally has a poor therapeutic response to nasal steroids because obstruction caused by the polyps prevents the nasal steroid from having its full effect. Initial systemic steroid therapy should induce a rapid polyp size reduction, which can then open up the nasal cavity to receive the full efficacy of the nasal steroids. In our study with this combination therapy, however, patients with nasal polyp grade 3 still had significantly less therapeutic improvement compared with those with smaller sizes, grades 1 and 2. Background cell resistance to corticosteroids in large nasal polyps with more severe inflammation has been suggested as a potential cause of such therapeutic failure.30 Increased expression of GRb in nasal polyposis has been proposed as a potential mechanism explaining steroid resistance and has been found to be inversely correlated with steroid responsiveness.31–34

Nasal polyps are often associated with chronic sinus inflammation. Infected sinus cavities can be a reservoir for pathogenic bacteria causing recurrent or persistent infection. Interactions between infectious stimuli and nasal polyps can also cause a poor treatment outcome.30 In our study, nasal polyps with positive meatal discharge, but not positive sinus radiography, showed a worse therapeutic response to combined oral and nasal steroid therapy compared with nasal polyps with negative meatal discharge. Abnormal sinus radiography could be the result of noninfectious inflammation and/or infection. Noninfectious sinus inflammation would be improved with the strong anti-inflammatory effect of initial administration of systemic steroids, with the effects being maintained by topical steroids. Positive meatal discharge is more likely to represent a true sinus infection and be associated with unfavorable response to steroid treatment. Allergy and asthma are frequently associated with nasal polyps, and patients with these conditions may have a poor medical response, worse surgical outcome, and more recurrences after sinus surgery.15–20 In the current study, with combined oral and nasal steroid therapy, neither a history of asthma and/or a positive allergy skin test were associated with a negative impact on clinical improvement. Initial administration of oral prednisolone, with its potent anti-inflammatory action, might be highly effective in the control of asthma and allergic inflammatory diseases associated with nasal polyposis. Only four patients in our study had aspirin sensitivity, and thus the numbers were too small to perform statistical comparisons with nonsensitive patients.

We note some limitations of this study. First, although conventional sinus radiography can be used as a screening method for rhinosinusitis,35,36 a number of false positive and false negative results have also been reported.37 Abnormal sinus radiography should be interpreted in the context of the clinical examination, nasal endoscopy, or both. Also, our assessment of disease severity was based on NSS, endoscopic findings, and nasal airflow, which may not be reliable enough to fully and accurately evaluate disease severity in the sinuses. A CT scan is the imaging modality of choice to provide more objective information for assessing the extent of sinonasal pathology; however, in some situations the availability of CT imaging is limited by cost and considerations of radiation dosage.36 Finally, our findings represent an examination of the short-term effects of initial oral steroids followed by topical steroid therapy in patients with nasal polyps, and longer clinical trials are necessary to examine the long-term therapeutic effects and identify reliable clinical predictors of this intervention.

CONCLUSION

The main findings of the current study were (1) nasal steroid therapy alone effectively improved nasal symptoms in nasal polyposis; (2) combined oral and nasal steroid therapy was more effective over 12 weeks than nasal steroid therapy alone in improving hyposmia, polyps size, and nasal airflow in nasal polyposis; (3) massive polyposis and/or positive meatal discharge can be considered as major risk factors for steroid insensitivity in patients with nasal polyposis.

Footnotes

Funded by the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare pertaining to this article

REFERENCES

- 1. Aouad RK, Chiu AG. State of the art treatment of nasal polyposis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 25:291–298, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joe SA, Thambi R, Huang J. A systematic review of the use of intranasal steroids in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 139:340–347, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Badia L, Lund V. Topical corticosteroids in nasal polyposis. Drugs 61:573–578, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dalziel K, Stein K, Round A, et al. Systematic review of endoscopic sinus surgery for nasal polyps. Health Technol Assess 7:1–159, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nores JM, Avant P, Bonfils P. Sino-nasal polyposis evaluation of the efficacy of combined local and general corticotherapy in a series of 100 consecutive patients with a 3-year follow-up. Bull Acad Natl Med 186:1643–1656, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benítez P, Alobid I, de Haro J, et al. A short course of oral prednisone followed by intranasal budesonide is an effective treatment of severe nasal polyps. Laryngoscope 116:770–775, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alobid I, Benitez P, Pujols L, et al. Severe nasal polyposis and its impact on quality of life. The effect of a short course of oral steroids followed by long-term intranasal steroid treatment. Rhinology 44:8–13, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaidyanathan S, Barnes M, Williamson P, et al. Treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis with oral steroids followed by topical steroids: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 154:293–302, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Norès JM, Avan P, Bonfils P. Medical management of nasal polyposis: A study in a series of 152 consecutive patients. Rhinology 41:97–102, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonfils P, Norès JM, Halimi P, Avan P. Corticosteroid treatment in nasal polyposis with a three-year follow-up period. Laryngoscope 113:683–687, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Slavin RG. Nasal polyps and sinusitis. JAMA 278:1849–1854, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Asero R, Bottazzi G. Nasal polyposis: A study of its association with airborne allergen hypersensitivity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 86:283–285, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bunnag C, Pacharee P, Vipulakom P, Siriyananda C. A study of allergic factors in nasal polyp patients. Ann Allergy 50:126–132, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirtsreesakul V, Atchariyasathian V. Nasal polyposis: Role of allergy on therapeutic response of eosinophil- and noneosinophil-dominated inflammation. Am J Rhinol 20:95–100, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Settipane GA. Nasal polyps and immunoglobulin E (IgE). Allergy Asthma Proc 17:269–273, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dursun E, Korkmaz H, Eryilmaz A, et al. Clinical predictors of long-term success after endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129:526–531, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bonfils P, Avan P. Non-specific bronchial hyperresponsiveness is a risk factor for steroid insensitivity in nasal polyposis. Acta Otolaryngol 124:290–296, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Albu S, Tomescu E, Mexca Z, et al. Recurrence rates in endonasal surgery for polyposis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 58:79–86, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Batra PS, Kern RC, Tripathi A, et al. Outcome analysis of ESS in patients with nasal polyps and asthma. Laryngoscope 113:1703–1706, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Amar YG, Frenkiel S, Sobol SE. Outcome analysis of ESS for chronic sinusitis in patients having Samter's Triad. J Otolaryngol 29:7–12, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirtsreesakul V, Wongsritrang K, Ruttanaphol S. Clinical efficacy of a short course of systemic steroids in nasal polyposis. Rhinology 49:525–532, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hissaria P, Smith W, Wormald PJ, et al. Short course of systemic corticosteroids in sinonasal polyposis: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with evaluation of outcome measures. J Allergy Clin Immunol 118:128–133, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Verbeek PR, Geerts WH. Nontapering versus tapering prednisone in acute exacerbations of asthma: A pilot trial. J Emerg Med 13:715–719, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nordin S, Bramerson A. Complaints of olfactory disorders: Epidemiology, assessment and clinical implications. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 8:10–15, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim DW, Kim JY, Jeon SY. The status of the olfactory cleft may predict postoperative olfactory function in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 25:e90–e94, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yee KK, Pribitkin EA, Cowart BJ, et al. Neuropathology of the olfactory mucosa in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 24:110–120, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mott AE, Cain WS, Lafreniere D, et al. Topical corticosteroid treatment of anosmia associated with nasal and sinus disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 123:367–372, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tos M, Svendstrup F, Arndal H, et al. Efficacy of an aqueous and a powder formulation of nasal budesonide compared in patients with nasal polyps. Am J Rhinol 12:183–189, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blomqvist EH, Lundblad L, Bergstedt H, Stjärne P. Placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study evaluating the efficacy of fluticasone propionate nasal spray for the treatment of patients with hyposmia/anosmia. Acta Otolaryngol 123:862–868, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim HY, Dhong HJ, Chung SK, et al. Prognostic factors of pediatric endoscopic sinus surgery. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 69:1535–1539, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adcock IM, Barnes PJ. Molecular mechanisms of corticosteroid resistance. Chest 134:394–401, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hamilos DL, Leung DY, Muro S, et al. GR beta expression in nasal polyp inflammatory cells and its relationship to the anti-inflammatory effects of intranasal fluticasone. J Allergy Clin Immunol 108:59–68, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mjaanes CM, Whelan GJ, Szefler SJ. Corticosteroid therapy in asthma: Predictors of responsiveness. Clin Chest Med 27:119–132, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ito K, Chung KF, Adcock IM. Update on glucocorticoid action and resistance. J Allergy Clin Immunol 117:522–543, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: Developing guidance for clinical trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol 118(suppl):S17–S61, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 137(suppl):S1–S31, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fokkens W, Lund V, Mullol J, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2007. Rhinology 20(suppl):1–136, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]