Abstract

Introduction

POTS is defined as the development of orthostatic symptoms associated with a heart rate (HR) increment ≥30, usually to ≥120 bpm without orthostatic hypotension. Symptoms of orthostatic intolerance are those due to brain hypoperfusion and those due to sympathetic overaction.

Methods

We provide a review of POTS based primarily on work from the Mayo Clinic.

Results

Females predominate over males by 5:1. Mean age of onset in adults is about 30 years and most patients are between the ages of 20–40 years. Pathophysiologic mechanisms (not mutually exclusive) include peripheral denervation, hypovolemia, venous pooling, β-receptor supersensitivity, psychologic mechanisms, and presumed impairment of brain stem regulation. Prolonged deconditioning may also interact with these mechanisms to exacerbate symptoms. The evaluation of POTS requires a focused history and examination, followed by tests that should include HUT, some estimation of volume status and preferably some evaluation of peripheral denervation and hyperadrenergic state. All patients with POTS require a high salt diet, copious fluids, and postural training. Many require β-receptor antagonists in small doses and low-dose vasoconstrictors. Somatic hypervigilance and psychologic factors are involved in a significant proportion of patients.

Conclusions

POTS is heterogeneous in presentation and mechanisms. Major mechanisms are denervation, hypovolemia, deconditioning, and hyperadrenergic state. Most patients can benefit from a pathophysiologically based regimen of management.

Keywords: POTS, hypovolemia, denervation, deconditioning, orthostatic, hyperadrenergic state

Introduction

Orthostatic intolerance is defined as the development of symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion or sympathetic activation while standing that is relieved by recumbency. Patients with orthostatic intolerance often present with complaints of exercise intolerance, lightheadedness, diminished concentration, tremulousness, nausea and recurrent syncope, and may be incorrectly labeled as having panic disorder or chronic anxiety.1 Simple activities such as eating, showering, or low-intensity exercise may profoundly exacerbate these symptoms and may significantly impair even the most rudimentary activities of daily living. Somewhat paradoxically, the magnitude of these symptoms is often significantly greater than those observed in patients with obvious clinically detectable autonomic failure.

Although neurogenic orthostatic hypotension (OH) due to the autonomic neuropathies, such as those of diabetes and amyloidosis, and nonneuropathic disorders such as MSA (multiple system atrophy; Shy-Drager syndrome) and PAF (pure autonomic failure; idiopathic orthostatic hypotension) are better known, these disorders are relatively uncommon. Most patients with orthostatic intolerance do not have florid autonomic failure and do not have OH. Improved recognition of lesser degrees of orthostatic intolerance came with the observation that the most common and the earliest manifestation of orthostatic intolerance is an excessive tachycardia.2 These subjects have disorders that are sometimes termed “benign” disorders of reduced orthostatic tolerance. The unifying feature is the development of orthostatic symptoms without consistent OH. Investigators and clinicians have been impressed with different aspects of the conditions and have approached orthostatic intolerance from different perspectives. Terms such as effort syndrome, neurasthenia, idiopathic hypovolemia,3 sympathotonic orthostatic hypotension, emphasizing sympathetic overactivity,4 and mitral valve prolapse syndrome5 exemplify the concentration on particular components of the patient’s disease. Postural tachycardia ± syncope can be present in several of the disorders. Some patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have orthostatic intolerance with tilt-induced syncope, and a subset will respond to treatment directed at syncope.6

We have focused on orthostatic tachycardia since an excessive HR increment appears to be the earliest and most consistent of the easily measured indices of orthostatic intolerance.7 Most of the other terms focus on manifestations that are not consistently present. The term idiopathic hypovolemia is unsatisfactory, since most patients do not have reduced plasma volumes or red cell mass. Current thinking is that the occurrence of mitral valve prolapse with POTS is fortuitous. The emphasis on postural tachycardia does, however, have a disadvantage in that it ignores nonorthostatic symptoms such as paroxysmal episodes of autonomic dysfunction, including sinus tachycardia, BP fluctuations, vasomotor (especially acral) symptoms, and fatigue.

The prevalence of POTS is unknown. In clinical practice, it is probably about 5–10 times as common as orthostatic hypotension. One estimate is the prevalence is at least 170/100,000.8 This is based on the investigators’ documentation that 40% of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have POTS.

Clinical Features

The age of presentation is most commonly between 15 and 50 years.9,10 Most patients that we have evaluated have had the symptoms for about one year. The orthostatic symptoms consist of symptoms of reduced cerebral perfusion coupled with those of sympathetic activation. The most common symptoms are lightheadedness, palpitations, symptoms of presyncope, tremulousness, and weakness or heaviness (especially of the legs). These symptoms are commonly exacerbated by heat and exercise (Table 1). Other common symptoms are shortness of breath and chest pain.11 The symptoms these patients experience differ from those of patients with orthostatic hypotension in that there are significant symptoms of sympathetic activation.12 There may be an overrepresentation of migraine, sleep disorders, and fatigue, and fibromyalgia is sometimes associated.1 There is a clear overrepresentation of women.11 We have found a consistent female:male ratio of 5:1.

TABLE 1.

Orthostatic Symptoms as Frequency (%) in Patients with POTS

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Orthostatic symptoms | ||

| Light headed or dizziness | 118 | 78 |

| Palpitations | 114 | 75 |

| Presyncope | 92 | 61 |

| Exacerbation by heat | 81 | 53 |

| Exacerbation by exercise | 81 | 53 |

| Sense of weakness | 76 | 50 |

| Tremulousness | 57 | 38 |

| Shortness of breath | 42 | 28 |

| Chest pain | 37 | 24 |

| Exacerbation by meals | 36 | 24 |

| Exacerbation associated with menses | 22 | 15 |

| Hyperhidrosis | 14 | 9 |

| Loss of sweating | 8 | 5 |

| Nonorthostatic symptoms | ||

| Nausea | 59 | 39 |

| Bloating | 36 | 24 |

| Diarrhea | 27 | 18 |

| Constipation | 23 | 15 |

| Abdominal pain | 23 | 15 |

| Bladder symptoms | 14 | 9 |

| Vomiting | 13 | 9 |

| Pupillary symptoms (glare) | 5 | 3 |

| Diffuse associated symptoms | ||

| Fatigue | 73 | 48 |

| Sleep disturbance | 48 | 32 |

| Migraine headache | 42 | 28 |

| Myofascial pain | 24 | 16 |

| Neuropathic type pain | 3 | 2 |

(From Thieben MJ, Sandroni P, Sletten DM, Benrud-Larson LM, Fealey RD, Vernino S, Lennon VA, Shen WK, Low PA. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 82:308–313, 2007. Modified with permission.)

Early studies suggested that approximately one-half of patients have an antecedent presumed viral illness,1,13 although recent experience suggests that this is less common. Another feature of POTS is the cyclical nature of the symptoms. Some females will have marked deterioration of their symptoms at certain stages of their menstrual cycle associated with significant weight and fluid changes. Typically, these patients have large fluctuations in their weights, sometimes up to 5 pounds. Others have cycles of several days of intense orthostatic intolerance followed by a similar period when their symptoms are less. Some patients have episodic symptoms at rest associated with changes in BP and HR that are unrelated to arrhythmias. The HR alterations are typically a sinus tachycardia, although a bradycardia can occur.14 Fatigue can be a problem during these episodes. Some describe periods when they have trouble retaining fluid, in spite of heavy intake. Studies of fluid balance and antidiuretic hormone levels are not well documented. Orthostatic intolerance with low BP requiring repeat visits to the emergency room for intravenous saline infusions is uncommon but by no means rare.

Fatigue is commonly present.11 Patients complain of poor exercise tolerance with physiological features including reduced stroke volume and reflex tachycardia typical of subjects who are deconditioned, such as in persons who have had prolonged bed rest.15 Coupled with the poor exercise tolerance, an excessively long recovery cycle following exercise is often described. Additionally, patients typically note that they have low energy, even at rest. The sense of fatigue will sometimes occur in cycles and may last days or even weeks and then lift.

Clinical examination reveals an excessive HR increment. Pulse pressure may be excessively reduced and there is marked beat–to-beat variability of both pulse pressure and HR. One clinical correlate is the difficulty in palpating a radial pulse with continued standing or with the performance of a Valsalva maneuver (Flack sign). Another clinical sign is the development of acral coldness. With continued standing, there may be venous prominence resulting in a blueness and even swelling of the feet.7

Evaluation of Suspected POTS

All patients need a detailed history to document the severity of orthostatic intolerance, its modifying factors and influence on activities of daily living. It is helpful to grade the severity of orthostatic intolerance, based on symptoms, standing time, and effect on activities of daily living (Table 2). A full autonomic system review should document autonomic systems involved and whether there are symptoms to suggest an autonomic neuropathy. Commonly associated disturbances such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, and migraine should be documented.

TABLE 2.

The Grading of Orthostatic Intolerance

| Grade |

| Normal orthostatic tolerance |

Grade I

|

Grade II

|

Grade III

|

Grade IV

|

| Syncope/presyncope is common if patient attempts to stand |

Symptoms may vary with time and state of hydration and circumstances.

Orthostatic stresses include prolonged standing, a meal, exertion, or heat stress.

HUT and Evaluation of Adrenergic Function

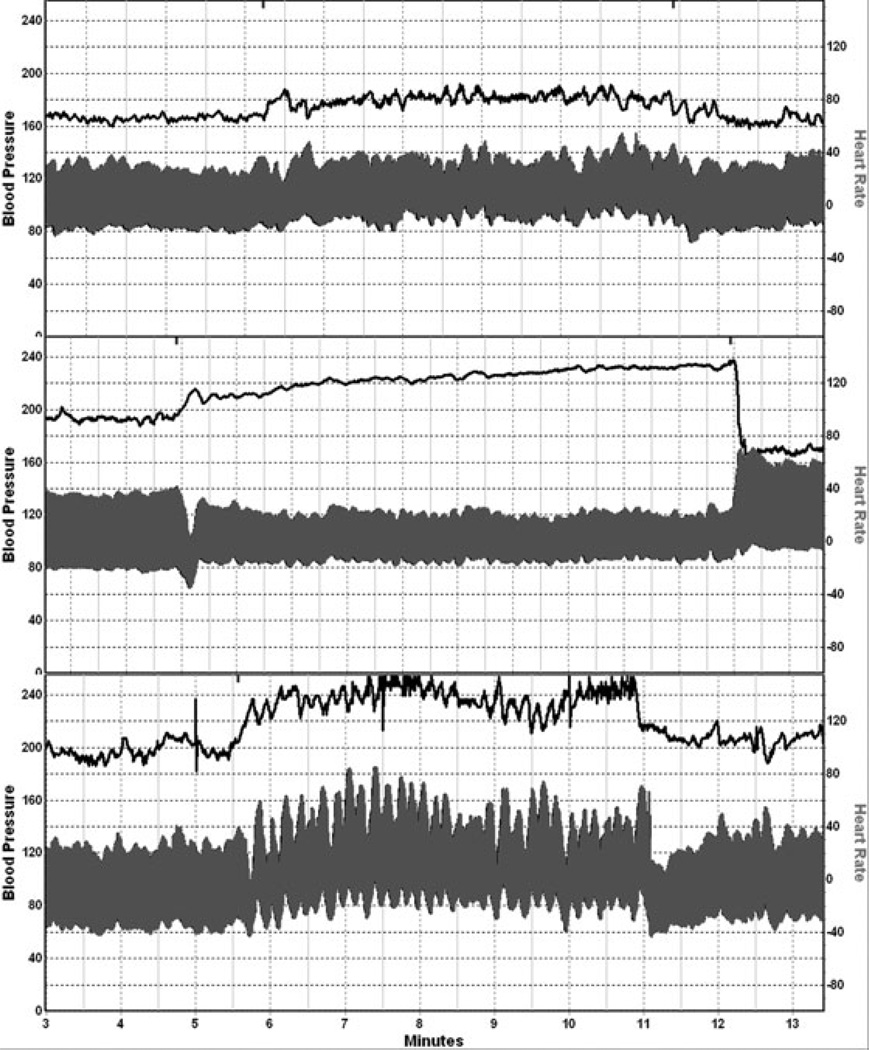

The evaluation of POTS is summarized in Table 3. Cardiovascular responses to HUT should be done with continuous recordings of BP and HR for a minimum of 10 minutes. The HR response in POTS varies from 120–170 bpm on HUT, and the patient typically attains these values by 5 minutes. Orthostatic intolerance is present when HUT results in a HR increment ≥30 bpm and associated with symptoms of orthostatic intolerance in patients ≥18 years. Sometimes the term mild orthostatic intolerance is used for patients who fulfill these criteria but remain <120 bpm. A fall in BP beyond 10 minutes (delayed orthostatic hypotension) occurs in about 40% of subjects and is associated with normal or near-normal adrenergic function.16 The HR response may oscillate excessively. The BP responses occur in several patterns. Patients with hypovolemia or excessive venous pooling may have an excessive reduction in pulse pressure. Some have a hypertensive SBP response (hyperadrenergic POTS (Fig. 1). Some patients have prominent fluctuations with increases in diastolic BP by up to 50 mmHg, with large fluctuations.

TABLE 3.

Evaluation of Suspected POTS

Routine Evaluation of POTS

|

Additional Tests

|

Figure 1.

Examples of blood pressure (BP) and heart rate recordings from a normal subject (top panel), a patient with neuropathic POTS (middle panel), and a patient with hyperadrenergic POTS (bottom panel). Note the modest reduction in BP in neuropathic POTS. Hyperadrenergic POTS is associated with prominent BP oscillations, an orthostatic increment in systolic BP, and a prominent norepinephrine response to head-up tilt.

Plasma catecholamines should be measured supine and after standing for 15 minutes. The primary interest is in norepinephrine. In about half the patients standing, norepinephrine exceeds 600 pg/mL, considered a hyperadrenergic response.11,14 A 24-hour urine sodium is a simple and helpful test that provides documentation that the patient is taking sufficient fluids and sodium. The goal is a volume of 1,500–2,500 mL and sodium excretion of 170 mmol/24 hours. The latter indicates that the patient is taking adequate sodium and likely has a normal plasma volume.17

The beat-to-beat BP and HR responses to the Valsalva maneuver are abnormal in about half the patients.12,13 The pulse pressure falls by more than 50% and may be obliterated. The Valsalva maneuver provides an estimate of both the vagal and adrenergic components of baroreflex sensitivity (BRS). By relating the fall in BP during phase II_E to heart period, vagal BRS (BRS_v) can be calculated.18–20 Baroreflex unloading results in the adrenergic component of the baroreflex with a rise in total peripheral resistance, manifested in the VM as II_L, and phase IV. Since the duration of expiratory pressure is short (10–15 seconds), II_L is not always generated and is often absent in normal subjects older than 60 years of age. Hence, this is an unreliable index of adrenergic baroreflex sensitivity (BRS_a). Phase IV is a better index but is subject to much variability. The most reliable index is BP recovery time (PRT), defined as time from phase III to return to baseline (in seconds).20 BRS_a can be better quantified by relating BRS_a to the preceding fall in BP.18,19

Some Varieties of POTS

A number of types of POTS have been described. The following is an abbreviated description from a large review.10

Neuropathic POTS

A number of phenotypes have been described. Three phenotypes (Table 4) are sufficiently well described. About half of patients with POTS have a restricted autonomic neuropathy with a length-dependent distribution of neuropathy.11,13 The term length-dependent neuropathy refers to one where the ends of the longer fibers are affected before the shorter ones. Distal postganglionic sudomotor denervation can be demonstrated with the quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test (QSART)21 or the thermoregulatory sweat test.22 These tests demonstrate sudomotor denervation to the foot and toes. Adrenergic impairment to the lower extremity can be seen in neuropathic POTS demonstrable as impaired norepinephrine spillover in the leg while the arm response remains normal.23 In the clinical laboratory, we have used a practical index of adrenergic denervation. When BP recovery time (PRT) ≥6 seconds in the age group of POTS, adrenergic denervation is likely.20 Support for the notion of neuropathic POTS comes also from the 1 in 7 patients who have low titer of A3 acetylcholine receptor antibodies,11 a finding that suggests an autoimmune attach of autonomic nerves.

TABLE 4.

Some Distinguishing Features of Common Types of POTS

| POTS Category | HR on HUT | BP on HUT | Plasma NE | QSART/TST | Ganglionic Antibody |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropathic | ↑↑ | Mild ↓ | N | Distal anhidrosis | Sometimes positive in low titers |

| Hyperadrenergic | ↑↑↑ | BP↑ | >600 pg/mL | Normal | Absent |

| Deconditioned | ↑ | PP ↓ | N or ↑ | Normal | Absent |

HUT = head-up tilt; PP = pulse pressure; QSART = quantitative sudomotor axon-reflex test; TST = thermoregulatory sweat test.

Hyperadrenergic POTS

One subset of POTS is characterized by an excessive increase of plasma norepinephrine and a rise of BP on standing.14,24 Hyperadrenergic POTS is defined as POTS associated with a systolic BP increment ≥10 mmHg during 10 minutes of HUT, and an orthostatic plasma norepinephrine ≥600 pg/mL (Fig. 1). These patients have similar HR increment to nonhyperadrenergic POTS, but tend to have prominent symptoms of sympathetic activation,24 such as palpitations, anxiety, tachycardia, and tremulousness. These patients have a larger fall in BP following ganglionic blockade with trimethaphan, and higher upright plasma norepinephrine levels than did nonhyperadrenergic POTS patients,24 presumably indicating a major role of orthostatic sympathetic activation. Elevation of plasma norepinephrine ≥600 pg/mL) was documented in 29.0% of patients tested in a recent study.11

POTS with Deconditioning

POTS patients have poor exercise tolerance, and deconditioning is often present, especially in patients with prominent fatigue and fibromyalgia type symptoms. In an attempt to segregate psychologic and exercise contributions, a study was designed to separate the roles of venous pooling and anxiety. During LBNP, the tachycardia in POTS patients was markedly blunted during LBNP with mast trouser inflation to 5 mmHg to prevent venous pooling, and there was no HR increase during vacuum application without LBNP in either group. HR responses during mental stress were not different in the patients and controls (18 ± 2 vs 19 ± 1 bpm; P > 0.6). Anxiety, somatic vigilance, and catastrophic cognitions were significantly higher in the patients (P < 0.05), but not related to the HR responses during LBNP or mental stress (P > 0.1). We concluded that although anxiety is commonly present in POTS, the HR response to orthostatic stress in POTS patients is not caused by anxiety, but is a physiological response that maintains arterial pressure during venous pooling. Masuki et al.15 studied 13 patients with mild POTS and 10 matched controls. Exercise was associated with a greater elevation in HR in POTS patients, especially while upright, was secondary to reduced stroke volume, and was associated with poor exercise tolerance. It was demonstrated that the tachycardia during exercise was due to a compensatory response to low stroke volume and not due to altered baroreflex function during exercise.15 Both the LBNP and exercise findings seem remarkably similar to models of pure deconditioning and bed rest. These findings in combination with the “somatic hypervigilance” noted above raise the possibility that in at least some POTS patients there was an initial event or illness that evoked orthostatic symptoms and that the symptoms were then “over-interpreted” and followed by reduced physical activity and deconditioning. In the context, the residual symptoms in POTS may have a strong deconditioning component in at least some patients.

Management

It is important to adopt a systematic, mechanism-based and practical approach.1,3,4,10,11,25

Step 1: Based on a detailed history, examination, and a general medical evaluation including EKG, it should be possible to decide if further evaluation is warranted. The degree of orthostatic intolerance should be graded (Table 2). The patient with POTS (standing HR >120 bpm, consistent orthostatic symptoms, significant impairment in ability to perform activities of daily living), that is, grades 3 or 4 by symptoms, should be further evaluated and treated. Many of the patients with mild orthostatic intolerance have a recognizable mechanism, and may not need detailed evaluation. Such a patient might be an individual with constitutional orthostatic intolerance, or deconditioning (patients confined to bed for more than a few days; debilitating illness), or hypovolemia.

Step 2: Once a decision to evaluate the patient is made, the study should comprise a cardiologic and autonomic laboratory evaluation. The cardiologic evaluation will usually comprise a cardiologic interview and examination, EKG, chest X-ray, and a 24-hour Holter monitor. A 24-hour Holter monitoring is useful to determine the mean heart rate, heart rate fluctuation according to activities, limited P-wave morphology from 3-standard leads, and correlation of symptoms to rate and rhythm. Additional heart rate assessment could be considered on an elective basis, including an ambulatory event loop recorder to correlation heart rate to symptoms and treadmill exercise test to assess heart rate response to activity.

A diagnostic electrophysiologic study is usually not indicated unless the etiology or mechanism of the documented tachycardia is uncertain or when other supraventricular tachyarrhythmias are suspected.26,27 During the study, programmed stimulation is performed to exclude sinus node reentry tachycardia, atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, ectopic atrial tachycardia, and atrial flutter or atrial fibrillation. Electrocardiographic and electrophysiological features for atrioventricular nodal tachycardia, atrioventricular tachycardia, atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation, distinguishable quite readily from sinus tachycardia, will not be discussed here. Differentiation of sinus tachycardia, sinus node reentrant tachycardia, and ectopic atrial tachycardia originating near the sinus node can be challenging. Several key features obtained during electrophysiologic study suggest the diagnosis of tachycardia from the sinus origin.

A gradual increase (warm-up) and decrease (cool-down) in heart rate spontaneously or during initiation and termination of isoproterenol infusion are consistent with an automatic mechanism of sinus node function.

The surface P-wave morphology is similar to that observed during sinus rhythm.

During mapping, the earliest endocardial activation is near the area of sinus node along the crista terminalis estimated from biplane fluoroscopic images, intracardiac ultrasonography, or advanced 3-D electroanatomic techniques. Atrial depolarization sequence is usually cranial-caudal along the crista terminalis. During rate changes, the site of earliest activation shifts up to the crista terminalis at a faster rate and down from the crista terminalis at a slower rate.

Step 3: The neurologic evaluation comprises a neurologic history, examination, and tests21 seeking evidence for an autonomic neuropathy. The autonomic laboratory evaluation follows and comprises a modified autonomic reflex screen and thermoregulatory sweat test, plasma catecholamines, and a 24-hour urinary sodium estimation (Table 3).

The cardiologic and autonomic evaluations are synthesized and treatment is planned. POTS is best considered a syndrome of orthostatic intolerance rather than a disease sui generis. It is reasonable to document the presence and severity of POTS, seek evidence of associated autonomic neuropathy, deconditioning or history of vasovagal syndrome. All patients are required to be educated on the pathophysiology of POTS, aggravating and ameliorating factors, so as to better handle the condition. All patients need to learn to maintain a high salt and high fluid intake. Some fine-tuning is helpful depending on pathophysiology. They need to recognize orthostatic stresses and how to avoid or minimize them. They need to be educated on measures that improve orthostatic tolerance. Three measures are often beneficial. The first is physical countermaneuvers. Patients are taught to contract muscles below the waist, typically for about 30 seconds, and the measure could be repeated.28,29 This method reduces venous capacity and increases total peripheral resistance. A second approach is to wear an abdominal binder. This reduces splanchnic-mesenteric venous capacity and is especially helpful in patients with poor venomotor tone or are hypovolemic.30,31 The third maneuver is water bolus therapy. The subject drinks two 8-ounce glasses of water sequentially. This results in a sympathetically-mediated pressor response that is sustained for 1–2 hours.32–35 Certain categories of POTS might additionally benefit from modifications of therapy based on pathophysiology (Table 5). There is significant overlap in management tools, and Table 5 is provided merely as a guide to emphasize main mechanisms and major emphases of management.

TABLE 5.

Approach to Treatment of Common Types of POTS

| POTS Category | Volume Expansion |

PCM and Compression |

Vasoconstrictors | Exercise | Usual Main Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropathic | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | Low-dose midodrine, with some volume expansion and compression |

| Hyperadrenergic | ++ | ++ | + | + | Volume expansion and reduce sympathetic action (central/peripheral) |

| Deconditioned/ hypovolemic | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | Sustained exercise program in deconditioned patient; volume expand |

+, ++, +++: slightly, moderately, very important.

The Hypovolemic Patient

The hypovolemic patient will do well with expanding plasma volume with generous salt intake and fludrocortisone. The salt intake should be between 150–250 mEq of sodium (10–20 g of salt). Some patients are intensely sensitive to salt intake and can fine-tune their plasma volume and BP control with salt intake alone. Foods with a high salt content include fast foods like hamburgers, hotdogs, chicken pieces, fries, and fish fries. Canned soups, chili, ham, bacon, sausage, additives like soya sauce, and commercially processed canned products also have a high sodium content. The patient should have at least 1 glass or cup of fluids with their meals and at least 2 at other times each day to obtain 2–2.5 L/day. Fludrocortisone, with doses up to 0.4 mg in young subjects, can be used initially, with the dose adjusted downwards to a maintenance dose of 0.1 to 0.2 mg/day.

Neuropathic POTS

The patient with peripheral adrenergic failure, manifested as a loss of late phase II or occasional or delayed OH, is best treated with fludrocortisone and an α-agonist. Midodrine appears to work best in terms of absorption, predictable duration of action, and lack of CNS side effects. The dose of midodrine is usually 5 mg 3 times a day. Some patients do better when midodrine is combined with pyridostigmine at the dose of 60 mg 3 times a day. Alternative agents such as ephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, and methylphenidate are largely of historical interest.

Hyperadrenergic POTS

These patients respond to orthostatic and other stresses with an exaggerated pressor and sometimes tachycardic response. It is important to minimize the orthostatic reduction in venous return and pulse pressure. To this end, volume expansion and wearing an abdominal binder are helpful. The latter reduces venous capacitance. Some patients are also helped by physical countermaneuvers, where the subject contracts dependent muscles. Some patients seem to be helped by propranolol (e.g., Inderal), a non-β-selective lipophilic agent at a dose of 10 mg/ day. Presumably, a significant part of its benefit is because of a central effect since it seems to work better than the β-selective lipophilic agent such as atenolol. A paticularly difficult subset of patients has unstable hypertensive responses to tilt. Some of these patients have BP responses up to 250/150 mmHg on standing. Some of these patients with autonomic instability respond to oral phenobarbital beginning with 60 mg at night and 15 mg q AM. An alternative treatment is clonidine or another α2 agonist. Clonidine is administered in a dose of 0.1 mg bid and increasing to the maximally tolerated doses. Reports of response to microvascular decompression of the brain-stem have been reported, but its role is as yet undefined.

Deconditioned POTS

The concept that at least some of the chronic symptoms in POTS are due in part to secondary deconditioning raises the possibility that a “life-hardening” exercise training program might have utility in this condition. This approach has been used in a number of studies of fibromyalgia patients and been successful in reducing disability, and clearly warrants serious consideration in POTS.36 A recent well-done study in POTS supports this approach.37 An exercise program, provided it is sustained and adequate for several months, can be very helpful.37 Based on the small study noted above, the physiological data, and anecdotal reports, larger clinical trial of exercise training in POTS may be warranted.

Conclusions

POTS is common and is heterogeneous in presentation and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Common mechanisms are denervation (neuropathic POTS), hyperadrenergic state, and deconditioning. Management always involves expansion of plasma volume with high salt and high fluid intake. Additional steps include compression garments. Medications that are commonly used include beta blockers, midodrine, and fludrocortisones. Exercise training and reconditioning is emerging as a very important strategy in the deconditioned subject.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Low is supported by research grants NS44233 and NS32352.

References

- 1.Low PA, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Textor SC, Benarroch EE, Shen WK, Schondorf R, Suarez GA, Rummans TA. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) Neurology. 1995;45:S19–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streeten DH, Anderson GH, Jr, Richardson R, Thomas FD. Abnormal orthostatic changes in blood pressure and heart rate in subjects with intact sympathetic nervous function: Evidence for excessive venous pooling. J Lab Clin Med. 1988;111:326–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fouad FM, Tadena Thome L, Bravo EL, Tarazi RC. Idiopathic hypovolemia. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:298–303. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-3-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoeldtke RD, Dworkin GE, Gaspar SR, Israel BC. Sympathotonic orthostatic hypotension: A report of four cases. Neurology. 1989;39:34–40. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coghlan HC, Phares P, Cowley M, Copley D, James TN. Dysautonomia in mitral valve prolapse. Am J Med. 1979;67:236–244. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bou-Holaigah I, Rowe PC, Kan J, Calkins H. The relationship between neurally mediated hypotension and the chronic fatigue syndrome. JAMA. 1995;274:961–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streeten DHP. Orthostatic Disorders of the Circulation, Mechanisms, Manifestations and Treatment. New York: Plenum Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schondorf R, Benoit J, Wein T, Phaneuf D. Orthostatic intolerance in the chronic fatigue syndrome. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1999;75:192–201. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(98)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural tachycardia syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:271. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Low PA. POTS. In: Low PA, Benarroch EE, editors. Clinical Autonomic Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: PA: Lippincott; 2008. pp. 515–533. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thieben M, Sandroni P, Sletten D, Benrud-Larson L, Fealey R, Vernino S, Lennon V, Shen W, Low PA. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome – Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:308–313. doi: 10.4065/82.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Low PA, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Textor SC, Schondorf R, Suarez GA, Fealey RD, Camilleri M. Comparison of the postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) with orthostatic hypotension due to autonomic failure. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1994;50:181–188. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: An attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia? Neurology. 1993;43:132–137. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garland EM, Raj SR, Black BK, Harris PA, Robertson D. The hemodynamic and neurohumoral phenotype of postural tachycardia syndrome. Neurology. 2007;69:790–798. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000267663.05398.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masuki S, Eisenach JH, Johnson CP, Dietz NM, Benrud-Larson LM, Schrage WG, Curry TB, Sandroni P, Low PA, Joyner MJ. Excessive heart rate response to orthostatic stress in postural tachycardia syndrome is not caused by anxiety. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:896–903. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00927.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Delayed orthostatic hypotension: A frequent cause of orthostatic intolerance. Neurology. 2006;67:28–32. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223828.28215.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Sayed H, Hainsworth R. Salt supplementation increases plasma volume and orthostatic tolerance in patients with unexplained syncope. Heart. 1996;75:134–140. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang CC, Sandroni P, Sletten D, Weigand S, Low PA. Effect of age on adrenergic and vagal baroreflex sensitivity in normal subjects. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:637–642. doi: 10.1002/mus.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrezenmaier C, Singer W, Muenter Swift N, Sletten D, Tanabe J, Low PA. Adrenergic and vagal baroreflex sensitivity in autonomic failure. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:381–386. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogel ER, Sandroni P, Low PA. Blood pressure recovery from Valsalva maneuver in patients with autonomic failure. Neurology. 2005;65:1533–1537. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000184504.13173.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Low PA. Autonomic nervous system function. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;10:14–27. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fealey RD, Low PA, Thomas JE. Thermoregulatory sweating abnormalities in diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:617–628. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacob G, Costa F, Shannon JR, Robertson RM, Wathen M, Stein M, Biaggioni I, Ertl A, Black B, Robertson D. The neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1008–1014. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010053431404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jordan J, Shannon JR, Diedrich A, Black BK, Robertson D. Increased sympathetic activation in idiopathic orthostatic intolerance: Role of systemic adrenoreceptor sensitivity. Hypertension. 2002;39:173–178. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.097202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grubb BP, Kanjwal Y, Kosinski DJ. The postural tachycardia syndrome: A concise guide to diagnosis and management. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:108–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brady PA, Low PA, Shen WK. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, and overlapping syndromes. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:1112–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen WK. How to manage patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:1015–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouvette CM, McPhee BR, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Low PA. Role of physical countermaneuvers in the management of orthostatic hypotension: Efficacy and biofeedback augmentation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:847–853. doi: 10.4065/71.9.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Lieshout JJ, ten Harkel AD, Wieling W. Physical manoeuvres for combating orthostatic dizziness in autonomic failure. Lancet. 1992;339:897–898. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90932-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denq JC, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Giuliani M, Felten J, Convertino VA, Low PA. Efficacy of compression of different capacitance beds in the amelioration of orthostatic hypotension. Clin Auton Res. 1997;7:321–326. doi: 10.1007/BF02267725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tani H, Singer W, McPhee BR, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Low PA. Splanchnic and systemic circulation in the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 1999;9:231–232. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan J, Shannon JR, Grogan E, Biaggioni I, Robertson D. A potent pressor response elicited by drinking water. Lancet. 1999;353:723. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)99015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordan J, Shannon JR, Black BK, Ali Y, Farley M, Costa F, Diedrich A, Robertson RM, Biaggioni I, Robertson D. The pressor response towater drinking in humans: A sympathetic reflex? Circulation. 2000;101:504–509. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.5.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroeder C, Bush VE, Norcliffe LJ, Luft FC, Tank J, Jordan J, Hainsworth R. Water drinking acutely improves orthostatic tolerance in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2002;106:2806–2811. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038921.64575.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shannon JR, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I, Tank J, Robertson RM, Robertson D, Jordan J. Water drinking as a treatment for orthostatic syndromes. Am J Med. 2002;112:355–360. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gowans SE, Dehueck A, Voss S, Silaj A, Abbey SE. Six-month and one-year followup of 23 weeks of aerobic exercise for individuals with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:890–898. doi: 10.1002/art.20828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winker R, Barth A, Bidmon D, Ponocny I, Weber M, Mayr O, Robertson D, Diedrich A, Maier R, Pilger A, Haber P, Rudiger HW. Endurance exercise training in orthostatic intolerance: A randomized, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2005;45:391–398. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000156540.25707.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]